Central Pacific Railroad: Map, History, Facts

Last revised: March 7, 2024

By: Adam Burns

From an operational standpoint the Central Pacific Railroad (CP) disappeared long ago and existed as a separate corporate entity only briefly before joining the Southern Pacific. However, it holds an important place in American history by helping establish the Transcontinental Railroad in conjunction with the Union Pacific.

When the two railroads met at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869 the country was finally linked with ribbons of steel, thus opening the West to commerce, trade, and settlement. This story is a fascinating tale of extreme hardship, determination, and virtually impossible odds.

The project was similar to reaching the moon a century later; no one believed it could be done until it actually happened. What's more, these men did it in a mere six years, hacking out new rights-of-way by hand.

In many ways, Central Pacific's endeavor was the more difficult as it had to build through the formidable Sierra Nevada Mountains.

One man knew it could be done, Theodore D. Judah, although he would fail to see "his" railroad completed. Today, the route he chose remains in general use under successor Union Pacific.

Photos

The replica of Central Pacific 4-4-0 #60, the "Jupiter," at the Golden Spike National Historic Site in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. This replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975 while the original was built by the Schenectady Locomotive Works of Schenectady, New York in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.

The replica of Central Pacific 4-4-0 #60, the "Jupiter," at the Golden Spike National Historic Site in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. This replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975 while the original was built by the Schenectady Locomotive Works of Schenectady, New York in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.History

The idea for what became the Transcontinental Railroad began long before the Civil War's outbreak. According to the book, "The Northern Pacific, Main Street Of The Northwest: A Pictorial History" by author and historian Charles R. Wood in the spring of 1853 Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (who later became president of the Confederate States of America) dispatched survey crews west of the Mississippi River in an effort to find suitable corridors to the Pacific Coast.

There were a total of eight different options put forth running various parallels from north to south. However, with the ongoing issue of slavery Congress could not decide on which. That all changed when Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th President of the United States on November 6, 1860.

At A Glance

Southern states immediately began to secede, starting with South Carolina on December 20, 1860. As a result, Northern congressmen and senators had the freedom to choose whichever route the wished and settled upon the central option.

This corridor had originally been conceived by noted engineer Greenville Dodge who believed departing from Omaha, Nebraska Territory was the most logical given its gentle grades along the Platte River nearly all the way into Colorado/Wyoming.

From there, a meeting point with the Central Pacific would be established somewhere between Utah Territory and the Nevada/California state line.

Pacific Railroad Act

The Pacific Railroad Act was passed through Congress during the spring of 1862 (the House passed the bill on May 6th by a 79-49 margin while the Senate did the same on June 20th by a 35-5 margin) and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 1st.

This legislation officially called for the creation of the aforementioned Union Pacific and provided the already-chartered Central Pacific (CP) with land grants and subsidies.

In his book detailing the Transcontinental Railroad's construction, "The Men Who Built The Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869: Nothing Like It In The World," author Stephen Ambrose points out the Central Pacific would likely never have existed without the tireless efforts of Theodore Judah.

While the so-called "Big Four" (Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker) are credited with financing and constructing the CP, Judah laid the groundwork. As early as 1859 he began lobbying Congress to fund a railroad over the Sierra Nevada's Donner Pass, the only natural passageway through this otherwise impenetrable granite wall.

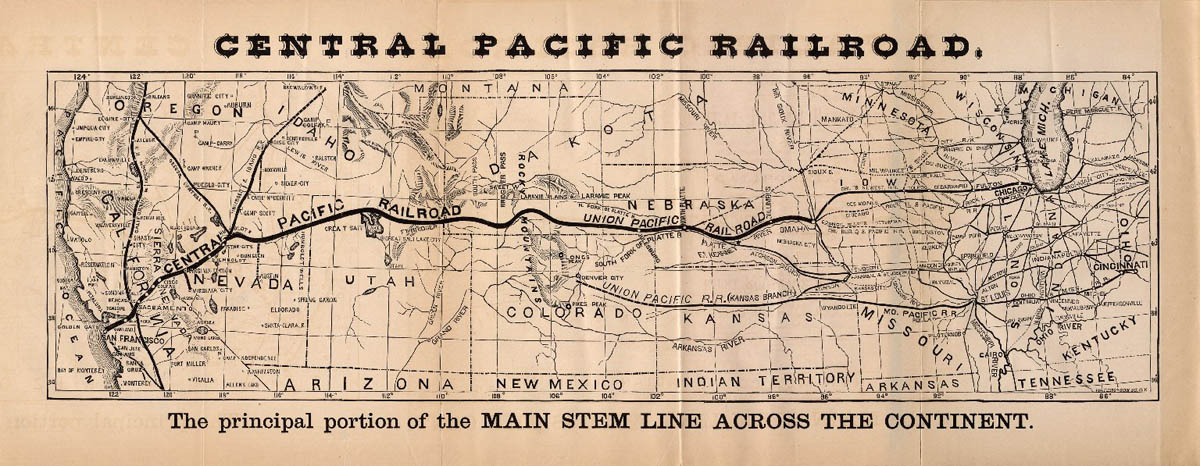

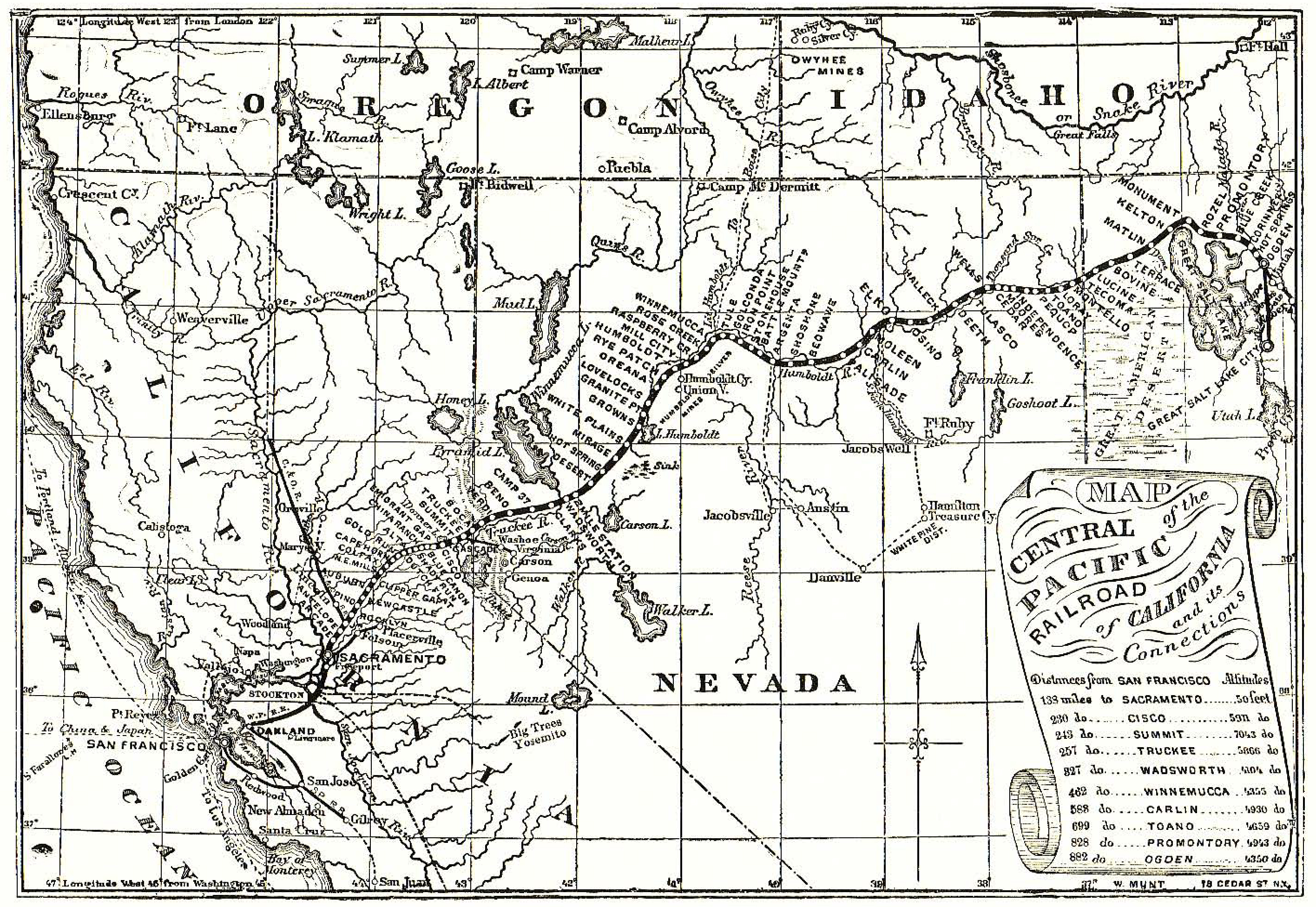

System Maps

Congress, even then, was excruciatingly slow at accomplishing anything and initially Judah struggled to make headway. He finally caught a break in 1860 when he opened what was dubbed the "Pacific Railroad Museum" inside the Capitol building to promote the venture. It was unveiled to the public on January 14th that year.

Not surprisingly there were many doubters and Judah was severely handicapped by not having the necessary survey maps and charts to convince naysayers. He wasted little time correcting this wrong and immediately sailed back to California with wife, Anna, and set about surveying the route on his own.

Route

It crossed the only natural passageway through the Sierras, Donner Pass, at an elevation of 7,056 feet and covered a total of 115 miles from the San Francisco Bay to Nevada state line. While in San Francisco he wrote up a lose incorporation for the "Central Pacific Railroad Company of California" on November 1, 1860 but finding no support in that town traveled to nearby Sacramento.

There, he found four local business owners eager and willing for just such a railroad; Charles Crocker, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Leland Stanford. With their monetary backing the group officially incorporated the Central Pacific Railroad of California on June 28, 1861.

It was directed to "construct a railroad and telegraph line from the Pacific coast, at or near San Francisco, or the navigable waters of the Sacramento River, to the eastern boundary of California." With the passage of the Pacific Railroad Act the CP adopted the agreement on October 7th and formally accepted it through the Department of the Interior on December 24th.

To aid in their efforts, Central Pacific was provided ten alternate sections in government land grants for each mile of track laid (or roughly 6,000 acres). According to the book, "Union Pacific Railroad," by historians Joe Welsh and Kevin Holland, an amended Pacific Railroad Act of 1864 increased this figure to twenty alternate sections (or around 12,000 acres for every mile completed).

Logo

Additionally, there were federal loans varying from $16,000 to $48,000 per mile, depending on the topography's ruggedness. As part of the deal, CP was required to complete 50 miles within its first two years, 50 miles each year thereafter, and be completed entirely by July 1, 1876 or lose its rights to these incentives.

In John Stover's book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," the author notes that between 1850 and 1871 the U.S. government offered railroads 170 million acres of land to construct 80 different projects.

Over this time about 131 million acres were actually used, which constituted 18,738 miles of new lines. The Central Pacific scheme was made more difficult by the simple issue of keeping the enterprise properly supplied with materials.

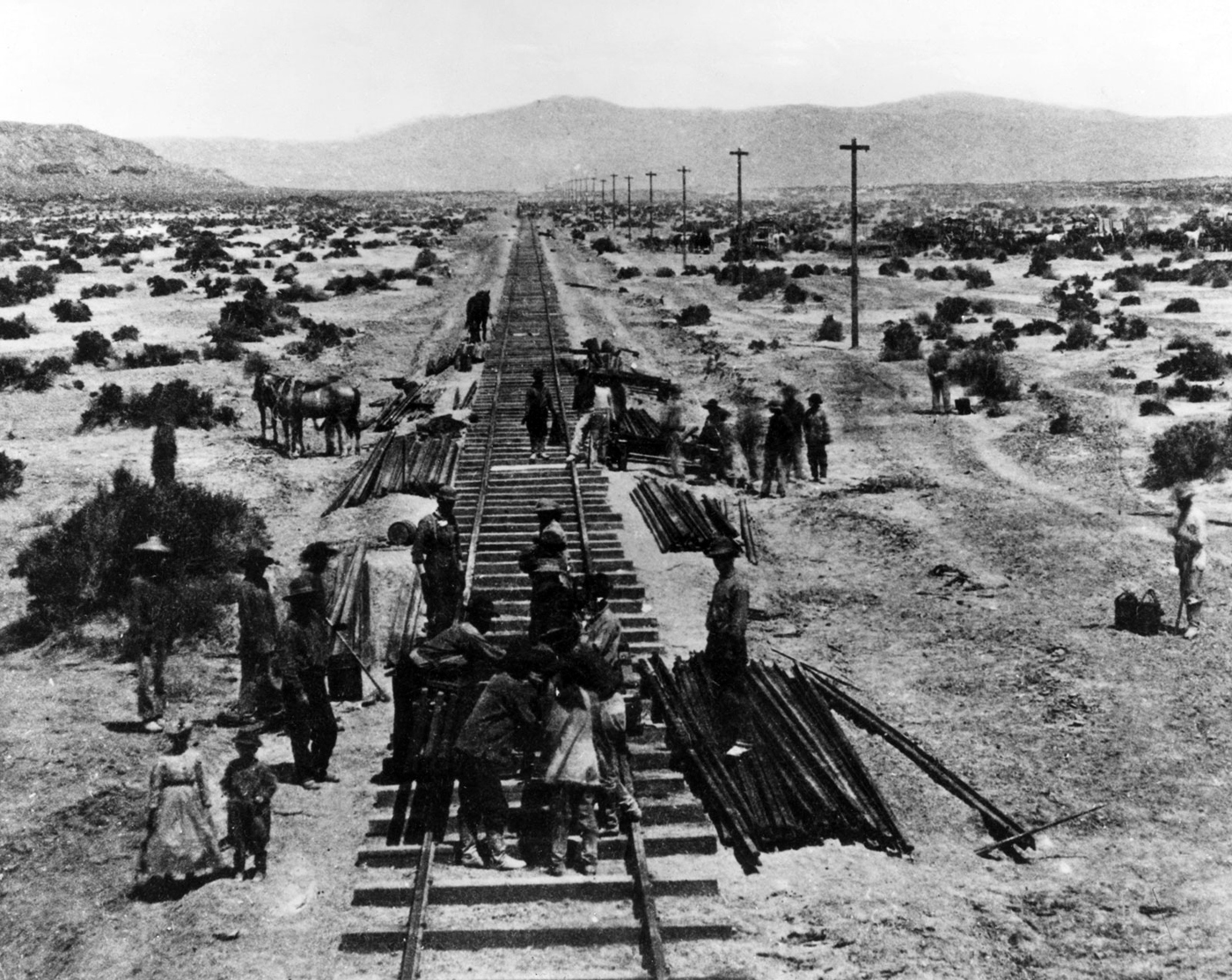

Construction

Whereas Union Pacific could simply deliver rails, tie-plates, spikes, and other needed products right no site this wasn't possible at CP aside from wooden ties which could be hacked out of local forests. Such things, which also included cars and locomotives, had to be transported in ocean-going vessels all of the way around South America's Cape Horn to reach California.

According to the book, "Railroads In The Days Of Steam," the arduous journey covered roughly 15,000 miles. This issue was resolved by Huntington; for his many faults he kept ships, sometimes dozens at a time, regularly dispatched to the west coast.

CP's groundbreaking took place on January 8, 1863 at K Street in Sacramento along the Sacramento River waterfront. Despite the great anticipation brought about by this event, behind the scenes a great tug-of-war ensued between Judah and the "Big Four."

He was highly critical of their leadership and disliked everything they did, from managerial decisions to monetary expenditures. Eventually, the "Big Four" were successful in pushing out their chief engineer (who also sat on the board).

In a last-ditch attempt to save what he fervently believed to be "his" railroad, Judah sailed to New York City on October 3, 1863 hoping to find a financial backer who could buy out Stanford, Huntington, Leland, and Crocker.

That person turned out to be none other than Cornelius Commodore Vanderbilt, the noted tycoon who was piecing together what later became the powerful New York Central System. It is unclear how truly interested the Commodore ever was in Judah's undertaking but, regardless, nothing came of it.

During his trip the engineer came down with a fever and died in New York on November 2, 1863. Afterwards, the project continued to languish for months until, finally, the first section from the waterfront to nearby 21st Street in Sacramento was completed on October 26, 1863.

Just a few weeks later on November 10th, CP's first locomotive, the 46-ton, 4-4-0 Governor Stanford (an 1862 product of the Norris Locomotive Works, this machine is preserved today at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento), made its first run over this trackage.

Brian Solomon points out in his book, "Southern Pacific Railroad," the CP initially received little funding from the successful "Big Four" and by 1865 had just 35 miles opened to Auburn. Afterwards, the pace quickened and they eventually did contribute a substantial percentage of their personal wealth to the project.

Through The Sierra-Nevadas

To help speed construction through the Sierras more than 14,000 Chinese immigrants were hired. With few mechanical devices then-available all grading, tunneling, fills, bridge components, and other aspects required were built by hand.

In July of 1867 rails reached the summit of Donner Pass but the work was slow, tedious, and extremely difficult. This was made all the more problematic by several bad winters that decade. The right-of-way roughly followed the North Fork of the American River as it passed through Colfax, Dutch Flat, and Emigrant Gap before reaching Summit Tunnel (tunnel #6) near present-day Norden.

As its name implied, this bore was right at the summit of Donner Pass and the longest of the fifteen bores needed to scale the mountains (excluding snow sheds); it was 1,659 feet in length, as deep as 124 feet, and required a year to complete (August, 1867).

It sat a 7,042 feet above sea-level and was been blasted out of the mountain using nothing more than picks, shovels, black powder, nitroglycerin, and considerable sweat and blood. It had so delayed work that grading crews pushed ahead into Nevada months.

Once the tunnel was finally finished, crews raced across northern Nevada, following the Humboldt River part of the way. The project then entered Utah where a famous feat of railroading has never since been duplicated.

As Earl Heath describes the story in an article from the January, 1943 issue of Trains Magazine entitled "Track-Laying Extravaganza," Charles Crocker bet Thomas C. Durant (Union Pacific's vice president and general manager) that his crews could lay 10 miles of track in a single day. CP's end-of-track was then at Corinne, Utah, just 14 miles from the agreed-upon meeting point, Promontory Summit.

The attempt was first made on April 27, 1869 but two miles into the race a locomotive derailed. So, they tried again the next day. A 7:15 AM the following morning crews of Irish, African-American, Chinese, Native American, Mexican, French Indiana, and other European backgrounds set out to achieve the impossible.

Despite individual rails weighing upwards of 560 pounds the men began moving so fast they were laying down nearly one new mile every hour! When the work concluded at 7 PM that evening they had laid 10 miles and an additional 56 feet of new railroad.

A replica of the Central Pacific depot in Old Sacramento, seen here at the California State Railroad Museum circa 1976. The original was completed during the 1860s and appears here as it would have circa 1876. William Myers photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A replica of the Central Pacific depot in Old Sacramento, seen here at the California State Railroad Museum circa 1976. The original was completed during the 1860s and appears here as it would have circa 1876. William Myers photo. American-Rails.com collection.Completion

The work was of such high quality a locomotive operated over the new track at 40 mph! Interestingly, Mr. Ambrose's book notes that as far as anyone knows, Durant never paid the $10,000 bet. Finally, amid a large, staged event during a major ceremony the railroads met at Promontory Summit, Utah took on May 10, 1869.

Numerous photos were taken, many now quite famous, depicting Central Pacific 4-4-0 #60, "The Jupiter," and Union Pacific 4-4-0 #119 facing coupler-to-coupler and surrounded by large crowds. Interestingly, Central Pacific's role in the annals of history more or less fades away following this milestone in American history.

Southern Pacific

One of the last notable projects it completed as an independent system was reaching Oakland/San Francisco.

As an arm of the "Big Four" the Central Pacific became part of their much larger plans and was swept up into the new Southern Pacific (via lease) on April 1, 1885. It subsequently remained a corporate entity until June 30, 1959 when the fabled corporation was finally dissolved.

While improvements and other upgrades to the original Donner Pass alignment have taken place over the years much of CP's original line remains in use under successor Union Pacific today.

Contents

SteamLocomotive.com

Wes Barris's SteamLocomotive.com is simply the best web resource on the study of steam locomotives.

It is difficult to truly articulate just how much material can be found at this website.

It is quite staggering and a must visit!