Steam Turbine Locomotives (USA): Pictures, 6-8-6, Length

Last revised: February 22, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The steam turbine locomotive was a variant of the steam

locomotive and hailed at the time of its development as not only

extremely efficient and powerful (which it was) but also that it could

compete with the diesel locomotive

in becoming the railroad industry's primary main line locomotive.

However, while powerful the design was only efficient at very high speeds and was a maintenance headache for the few railroads which did test them.

In all just the Union Pacific, Pennsylvania Railroad, Norfolk & Western, New York Central, Great Northern, and Chesapeake & Ohio ultimately tested designs of the steam turbine locomotive, which lasted just a few years on each railroad.

The C&O and N&W, in particular, had serious interest in developing a reliable product; each railroad maintained significant coal holdings in western Virginia and southern West Virginia. As a result, fuel for their design would have been practically free.

Alas, the limitations and issues could never be ironed out. The C&O was unable to put their locomotive into service while the N&W had scrapped its Jawn Henry by 1958. Today, no examples of this unique design are known to exist.

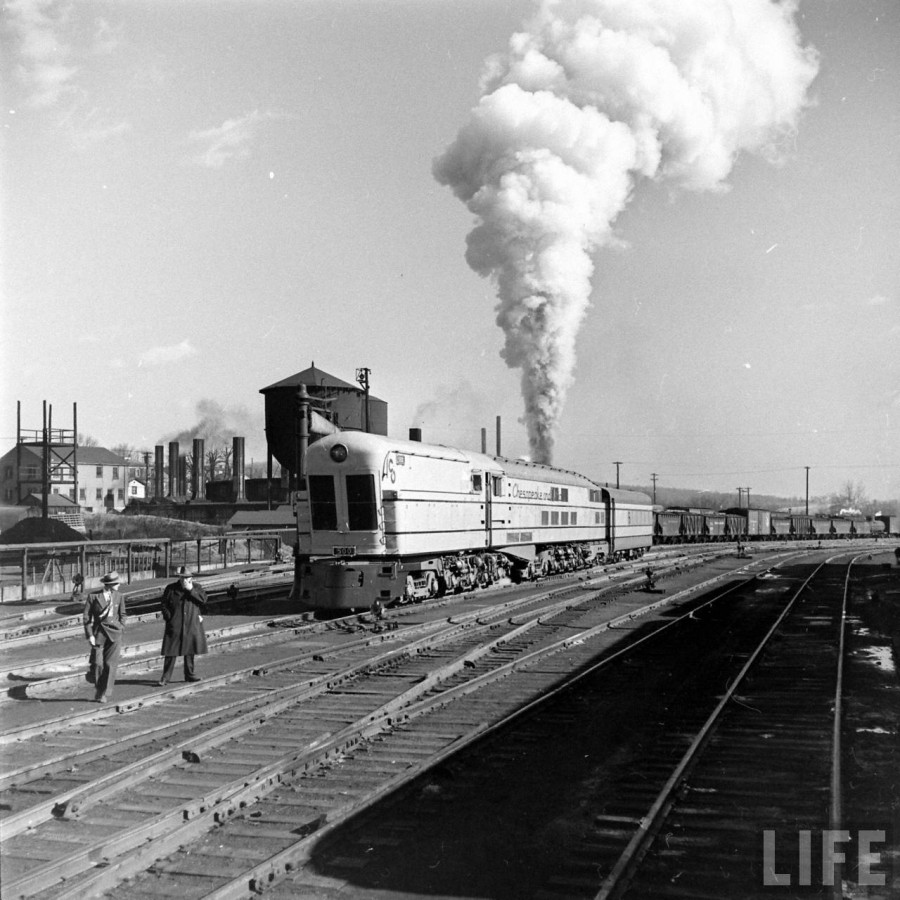

One of the Chesapeake & Ohio's massive Class M-1 steam turbines, #502, is seen here in Cincinnati on July 2, 1949.

One of the Chesapeake & Ohio's massive Class M-1 steam turbines, #502, is seen here in Cincinnati on July 2, 1949.The steam turbine locomotive was developed in the late 1930s as a means to compete with the diesel. By this point EMD had successfully demonstrated the usefulness of its E and F series diesel locomotives and the steam turbine seemed to be the last hope of retaining that means of propulsion in main line railroading.

In a comparison to steam locomotives only the steam turbine was meant to be more efficient while requiring less maintenance due to fewer moving parts. This was because the design did not have large driving wheels, side rods, or pistons like a standard reciprocating steam locomotive.

Instead, its running gear was much more similar to a diesel locomotive using traction motors and trucks to house the wheels (except for the PRR's model which did use a more conventional steam locomotive wheel arrangement).

The steam turbine had plenty of advantages but unfortunately had just as many disadvantages. Aside from having fewer moving parts the design did not have to contend with the difficult task of being properly balanced. Likewise, the locomotive did not suffer from wheel slippage when attempting to start from a dead stop.

However, the design was only efficient at very high speeds, usually over 75 mph and at slow speeds used massive amounts of fuel (coal) and water.

Additionally, the turbine an only be operated in one direction requiring an additional unit to be operated in reserve. Finally, the design proved to be a maintenance nightmare as the unclean environment in which railroads operated was simply not suited for a turbine.

The first steam turbine locomotive design was built by General Electric in 1938 and tested on the Union Pacific. The two test models carried an electric locomotive-like 2-C+C-2 wheel arrangement. To give you an idea of what this means, in the case of a 1-D-1 wheel arrangement:

- "1" refers to one unpowered axle located on each end of the locomotive

- "D" refers to four powered axles (whereby “A” equals one powered axle, “B” equals two powered axles, “C” equals three powered axles, and so on)

While at first these classifications look tricky they are actually quite simple once you know what they mean and stand for.

They were the only two steam turbine locomotive design to feature condensers and apparently worked relatively well. In any event, they were only used on the Union Pacific for about six months and were later sent to both the New York Central and Great Northern.

The GN used them throughout 1943 and returned them to GE needing new wheels. They remained sidelined at GE and were eventually scrapped.

A year later, in 1944 the Pennsylvania Railroad unveiled their steam locomotive turbine design the Class S2, #6200, developed by the Baldwin Locomotive Works. It featured a traditional steam locomotive wheel setup in the 6-8-6 arrangement.

The model could produce an astounding 6,900 horsepower with a starting tractive effort of 70,500 pounds. However, it consumed large amounts of fuel and water and low speeds and proved to be uneconomical.

The PRR would eventually scrap the #6200 by 1949. A year after the PRR first began testing its Class S2 the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway unveiled its Class M-1 in 1945, developed by both Baldwin and Westinghouse.

This design carried a unique albeit odd 2-C1+2-C1-B wheel arrangement and was streamlined for premier passenger service across Virginia, West Virginia, and Ohio. It was capable of producing 6,000 horsepower and the C&O eventually would come to own three, #500 through #502.

The steam turbine locomotive weighed an incredible 428 tons making it very hard on the track. Once again, this design proved to be quite troublesome, constantly breaking down due to water leaking on to the locomotives' traction motors and coal dust clogging the front motors.

By the summer of 1948 the C&O had scrapped all three of its steam turbines. Finally, in 1954 the Norfolk & Western Railway tested its "Jawn Henry" design, #2300, named after the famous African American worker who defeated a steam drill.

This design featured a C-C-C-C wheel arrangement and could produce nearly 5,000 horsepower. Like nearly all of the designs it was quite heavy at 409 tons but produced the highest tractive effort at 175,000 pounds.

Even as the master of steam technology, the N&W could not work out all of the problems that cropped up with its steam turbine locomotive. Within four years of its debut the "Jawn Henry" was scrapped by the railroad.

The length of the steam turbines mentioned above varied but generally much longer than a traditional steam locomotive; the Pennsylvania Railroad's 6-8-6 topped out at 122 feet, 7 1⁄4 inches while N&W's Jawn Henry was 161 feet, 1 1/2 inches with tenders (the engine alone was 111 feet 7, 1/2 inches).

Recent Articles

-

Texas's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 08, 26 12:30 PM

This article invites you on a metaphorical journey through some of these unique wine tasting train experiences in Texas. -

New York's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 08, 26 11:32 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

California Dinner Train Rides In Sacramento!

Jan 08, 26 11:21 AM

Just minutes from downtown Sacramento, the River Fox Train has carved out a niche that’s equal parts scenic railroad, social outing, and “pick-your-own-adventure” evening on the rails. -

New Jersey Dinner Train Rides In Woodstown!

Jan 08, 26 10:31 AM

For visitors who love experiences (not just attractions), Woodstown Central’s dinner-and-dining style trains have become a signature offering—especially for couples’ nights out, small friend groups, a… -

Nevada's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 02:12 PM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 02:08 PM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

Kansas's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 01:53 PM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Michigan's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 12:36 PM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

Indiana's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 12:33 PM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 12:30 PM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Thomas The Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 12:26 PM

If you’ve got a Thomas fan in the house, Day Out With Thomas at the Kentucky Railway Museum is one of those “circle it on the calendar” weekends. -

Michigan's Thomas The Train Rides

Jan 07, 26 12:10 PM

If you’ve got a Thomas fan in the house, few spring outings feel as “storybook-real” as Day Out With Thomas™ at Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR!

Jan 07, 26 11:36 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides In Boone!

Jan 07, 26 11:06 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

Wisconsin Dinner Train Rides In North Freedom!

Jan 06, 26 10:18 PM

Featured here is a practical guide to Mid-Continent’s dining train concept—what the experience is like, the kinds of menus the museum has offered, and what to expect when you book. -

Pennsylvania Dinner Train Rides In Boyertown!

Jan 06, 26 06:48 PM

With beautifully restored vintage equipment, carefully curated menus, and theatrical storytelling woven into each trip, the Colebrookdale Railroad offers far more than a simple meal on rails. -

North Carolina ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Ride

Jan 06, 26 11:26 AM

While there are currently no murder mystery dinner trains in the Tarheel State the Burgaw Depot does host a murder mystery dinner experience in September! -

Florida's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 06, 26 11:23 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

New Mexico's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 06, 26 11:19 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 06, 26 11:14 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries.