New York Central Railroad: Map, History, Logo

Last revised: October 16, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The storied history of the New York Central Railroad can trace its heritage back to one of our country's earliest railroads while its rise into one of the nation's largest lines is credited to a legendary tycoon and industrialist.

The NYC always remembered its roots and named a prominent passenger train after the "Commodore" while its flagship 20th Century Limited is still regarded as arguably the finest passenger train ever operated.

For history’s sake you cannot really speak of the NYC without also mentioning rival Pennsylvania Railroad (and vice versa).

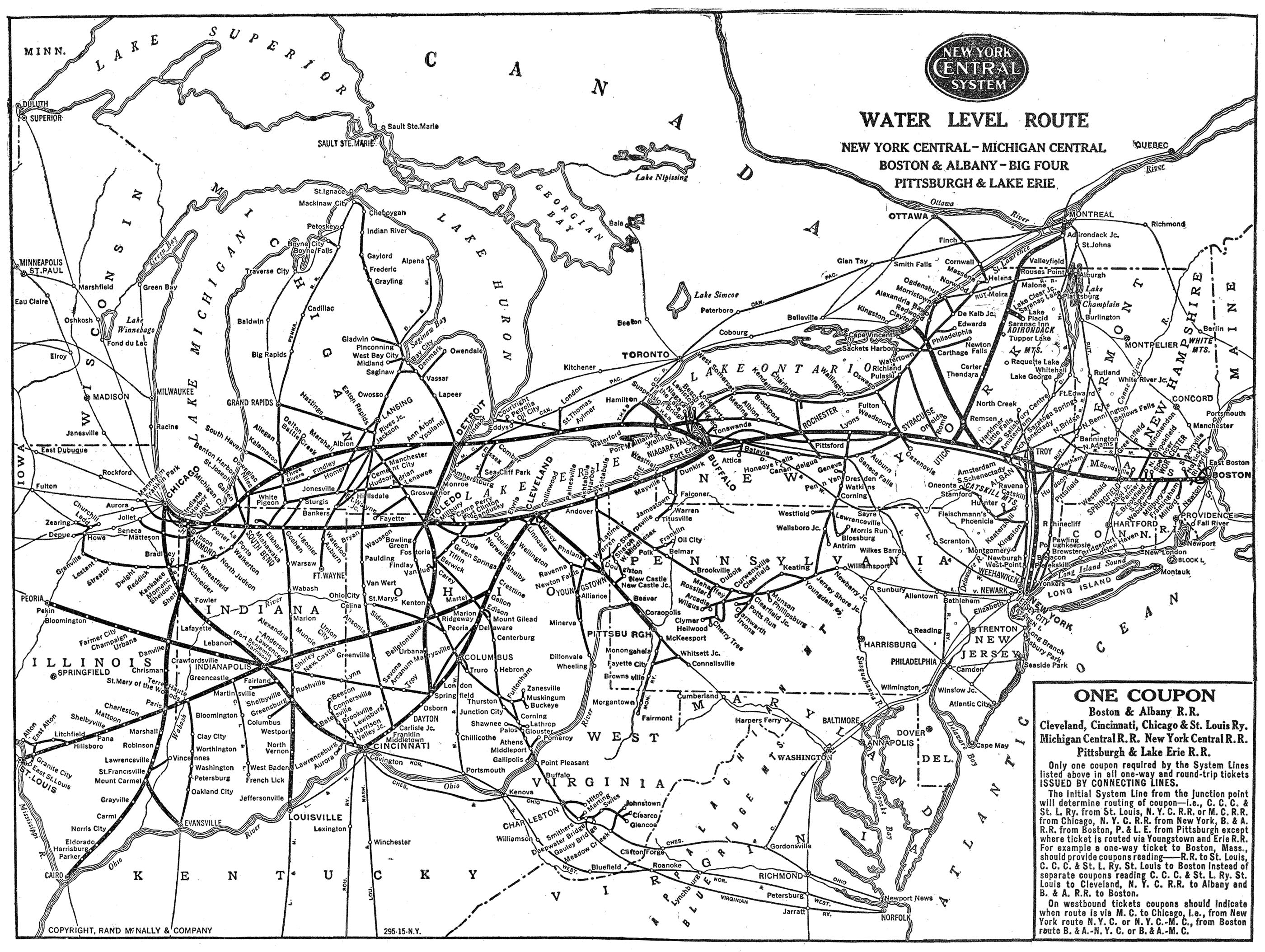

Both lines competed in many of the same markets stretching from New York City, across Ohio, through Indiana, and terminating at the Midwestern gateways of St. Louis, Chicago, Indianapolis, Detroit, and Cincinnati.

The PRR and NYC were institutions of their industry and today, many of the Central's main lines remain in service under CSX Transportation.

An American Locomotive photo featuring freshly out-shopped New York Central PA-2 #4210, circa 1950. Warren Calloway collection.

An American Locomotive photo featuring freshly out-shopped New York Central PA-2 #4210, circa 1950. Warren Calloway collection.History

The modern New York Central was a collection of predecessor properties which merged or were acquired over many years. The earliest component was one of the industry's pioneers, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad.

The M&H was incorporated on April 17, 1826, although as early as December 28, 1825 the local public was given word it was soon to be built thanks to a newspaper article (the Schenectady Cabinet) by George Featherstonhaugh.

The M&H holds historical significance as one of the earliest railroads ever chartered and built, opening 16 miles between Albany and Schenectady on August 9, 1831. At first, it primarily handled only passenger traffic since New York had recently opened the Erie Canal.

In an effort to pay for this public works project, the state restricted railroads from handling the more lucrative freight movements or do so by paying a toll. The other early predecessors of the NYC dealt with similar issues, finding it difficult moving freight in the face of state opposition.

At A Glance

West Shore Railroad Boston & Albany Toledo & Ohio Central Railway Zanesville & Western Railway Kanawha & Michigan Railway Michigan Central Railroad Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway (Big Four Route) Cincinnati Northern Railroad Peoria & Eastern Railway Evansville, Indianapolis & Terre Haute Railway Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Indiana Harbor Belt Chicago River & Indiana Railroad Chicago Junction Railway |

|

Diesels: 1,965 Electric: 65 |

|

Freight Cars: 94,115 Passenger Cars: 2,905 |

|

Despite transporting predominantly only passengers early on the Mohawk & Hudson did relatively well and is even credited with operating the first covered freight car, the boxcar, in 1833 (essentially a covered gondola) while it also placed the first steam locomotive into service when the DeWitt Clinton, an American-built 0-4-0 model, entered service on the M&H's first day of operation.

New York Central F3A's #1630 and #1631 in a publicity photo for the "Pacemaker" high-speed freight service (also the name of a passenger consist serving the New York - Cleveland - Chicago market) taken at Indianapolis, Indiana in November of 1949.

New York Central F3A's #1630 and #1631 in a publicity photo for the "Pacemaker" high-speed freight service (also the name of a passenger consist serving the New York - Cleveland - Chicago market) taken at Indianapolis, Indiana in November of 1949.Six other small roads comprised what later became the NYC's main line between Albany and Buffalo. These systems included the Utica & Schenectady, Syracuse & Utica, Auburn & Syracuse, Auburn & Rochester, Tonawanda Railroad, and Attica & Buffalo.

The U&S was chartered on April 29, 1833 and opened 78 miles between its namesake cities in 1836. It proved how successful railroads could become, moving many passengers, despite the state regulations placed upon it.

At Utica, the Syracuse & Utica was chartered on May 11, 1836 to extend rail service westward to Syracuse, opening a 53-mile route in August of 1839.

A New York Central T-motor (T-3a) handles a coach and two baggage cars at High Bridge, New York in the Bronx, circa 1952. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A New York Central T-motor (T-3a) handles a coach and two baggage cars at High Bridge, New York in the Bronx, circa 1952. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.The next component was the Auburn & Syracuse, chartered on May 1, 1834 it opened between both cities in January of 1838. The road was initially horse powered but introduced steam power a little more than a year later when the locomotive Syracuse entered service on June 14, 1839.

The A&S merged with the Auburn & Rochester in August of 1850 to form the Rochester and Syracuse Railroad. The A&R was chartered on May 13, 1836 and extended west as far as Rochester by late 1842.

At the latter city the system connected with the Tonawanda Railroad, interestingly the earliest chartered system of the bunch except for the Mohawk & Hudson. It had been formed on April 24, 1832, opening to Batavia in 1837. The final push into Buffalo came by way of the Attica & Buffalo Railroad, chartered in 1836.

Following a few years of construction it opened on November 24, 1842 between Buffalo and Attica, thus completing direct rail service from the state capital to Lake Erie.

Logo

According to Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon's book, "New York Central Railroad," the state discontinued canal tolls on these railroads during December of 1851. The results were nearly instantaneous as profits soared.

A few years prior to this event, merger talks had already been launched between the group as they understood the benefits of a unified line offering through service.

The consolidation was officially carried out on May 17, 1853 when they formally joined to form the original New York Central Railroad.

The first NYC expanded slightly over the next decade but essentially remained the same system linking the aforementioned endpoints until after the Civil War when Cornelius Vanderbilt acquired control of the property.

It was under the Commodore's guidance that the modern New York Central was born as he pieced together several large railroads into a network under common management stretching from New York to Chicago.

A New York Central FA-2 set, led by #1097, lays over at Zearing, Illinois in June, 1966. Rick Burn photo.

A New York Central FA-2 set, led by #1097, lays over at Zearing, Illinois in June, 1966. Rick Burn photo."Commodore" Vanderbilt

Enter Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose name remains synonymous with the New York Central Railroad. He was born in 1794 and at the age of 16 began his own ferry service between Staten Island and New York City.

Business savvy, Vanderbilt established a successful steamship operation and earned the title of Commodore by operating the largest schooner on the Hudson River.

He was worth a half-million dollars by 1834 and remained in the shipping industry for another three decades before realizing the future of transportation lay in the railroad.

In 1863 he acquired control of the New York & Harlem and a year later owned controlling interest in the Hudson River Railroad. These two roads provided the later NYC with a coveted entry into downtown Manhattan, an advantage the railroad maintained until the Pennsylvania Railroad opened Pennsylvania Station in 1910.

New York Central's westbound "Knickerbocker," led by E8A #4087, backs into St. Louis Union Station on June 23, 1957. American-Rails.com collection.

New York Central's westbound "Knickerbocker," led by E8A #4087, backs into St. Louis Union Station on June 23, 1957. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

The NY&H, originally operated as a horse-drawn system, had been incorporated on April 25, 1831 to open service on the east side of New York's Manhattan Island from the downtown region to the uptown community of Harlem.

It reached as far as Fordham, in the Bronx, in 1841 and then pushed far beyond the city over the next few years when it opened to Chatham, New York (129 miles away) during 1852 where a connection was established with the Western Railroad (later Boston & Albany).

The nearby Hudson River Railroad (HRRR) was a future competitor to the NY&H. It was chartered on May 12, 1846 to extend from Rensselaer, New York (a connection here was made with the Troy & Greenbush Railroad, later leased by the HRRR) down the eastern shore of the Hudson River until terminating along the western side of Manhattan, opening on October 3, 1851.

This became part of the NYC's future "Water Level Route" high-speed main line. Through shrewd business practices the Commodore gained control of the original New York Central Railroad in 1867.

He then formed a new company, the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad in 1869; the HRRR and NYC were merged into the new operation while the Harlem was leased.

A pair of New York Central F3A's (only a few months old) showcase new Merchants Despatch Transportation reefers in a publicity photo taken near Churchville, New York in October of 1947. Ed Nowak photo.

A pair of New York Central F3A's (only a few months old) showcase new Merchants Despatch Transportation reefers in a publicity photo taken near Churchville, New York in October of 1947. Ed Nowak photo.The Commodore's acquisition could not have arrived at a better time as the New York region's population was exploding and the railroad now boasted a through route to Buffalo. He expanded its presence across the city and then eyed a western extension.

In another move that could be described as somewhat manipulative, Vanderbilt gained control of what would prove perhaps the Central's greatest addition, the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway. This very large Midwestern line had a history tracing as far back as the 1830s and grew through a combination of takeovers and mergers.

At its peak the LS&MS connected Buffalo with Chicago via Toledo, Cleveland, and Elkhart. It also reached Detroit, southern parts of Michigan, and Oil City, Pennsylvania. In 1877 Vanderbilt finally acquired stock control of the road and the company's name later disappeared when the modern NYC was created.

The next major addition was the Michigan Central Railroad. This system began as the Detroit & St. Joseph of 1831 to connect its namesake cities. As monetary troubles mounted it was renamed as the Michigan Central in 1846 and slowly expanded during the next several decades.

By the late 19th century it connected Chicago, Detroit, Jackson, Mackinaw, and Toledo. Perhaps its most important artery was the route through southern Ontario known as the Canadian Southern (CASO) which linked Detroit with Buffalo.

At its peak the MC owned a system stretching over 1,800 miles. The Commodore had difficulty securing ownership of the property and it was not within the NYC's grasp until 1878, a year after he passed away.

The MC's addition offered the Central the best route from New England to the Midwest, cutting across the northern shore of Lake Erie, instead of going around it to the south. The CASO proved a very important corridor and remained so throughout the NYC's years.

The last piece added to Vanderbilt's empire during his lifetime was the Boston & Albany Railroad. Technically, this system was not actually under his control before he passed but the two had worked together for many years during his involvement.

The B&A can trace its roots back to the Boston & Worcester chartered on June 23, 1831 to connect those two cities, opening on July 3, 1835. The B&W was a quick success and had soon expanded further westward by incorporating the Western Railroad during March of 1833.

This well-engineered route was the work of Major George Whistler who designed a low-grade line through the rugged central and western mountains of Massachusetts. The WRR opened to Springfield in 1839 and was finished to the state line in 1841.

On September 4, 1867 the WRR and B&W merged to form the Boston & Albany as a double-tracked route running across Massachusetts. At its peak the B&A main line ran between its namesake cities while short branches reached such locations as Winchendon, North Adams, Webster, Milford, and Saxsonville.

After Vanderbilt

The Commodore's death did not slow the Central's expansion as it attempted to keep up with a system proving itself a noteworthy competitor, the Pennsylvania Railroad. Its last great addition was the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway, better known as simply the "Big Four."

The history of this system could fill a book by itself but in short it was created on June 30, 1889 when the NYC&HR merged three predecessors into one. Interestingly, the Vanderbilt system did not actually lease the property, thereby acquiring direct control, until 1930.

These smaller railroads included the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis (the "Bee Line"); Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis & Chicago (the first given the nickname "Big Four"); and the Indianapolis & St. Louis.

The heritage of the Big Four traces back to the 1830s while at its largest the system boasted an impressive network of nearly 2,400 route miles.

It constituted almost the entirety of the Central's network across Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois reaching such cities as Indianapolis, St. Louis, Louisville, Cincinnati, Columbus, and another link to Chicago.

There were several other takeovers and acquisitions throughout the years but the above-mentioned properties formed the bulk of the modern-day New York Central Railroad. One of the most important smaller systems was the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie, which provided the Central access to the Steel City.

While it never served Pittsburgh via a through route, like the Pennsy, the P&LE nevertheless proved itself a money-maker and coveted subsidiary. It was formed on May 11, 1875 and largely funded by steel tycoon, Andrew Carnegie. In addition, it later saw extensions to Brownsville and Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

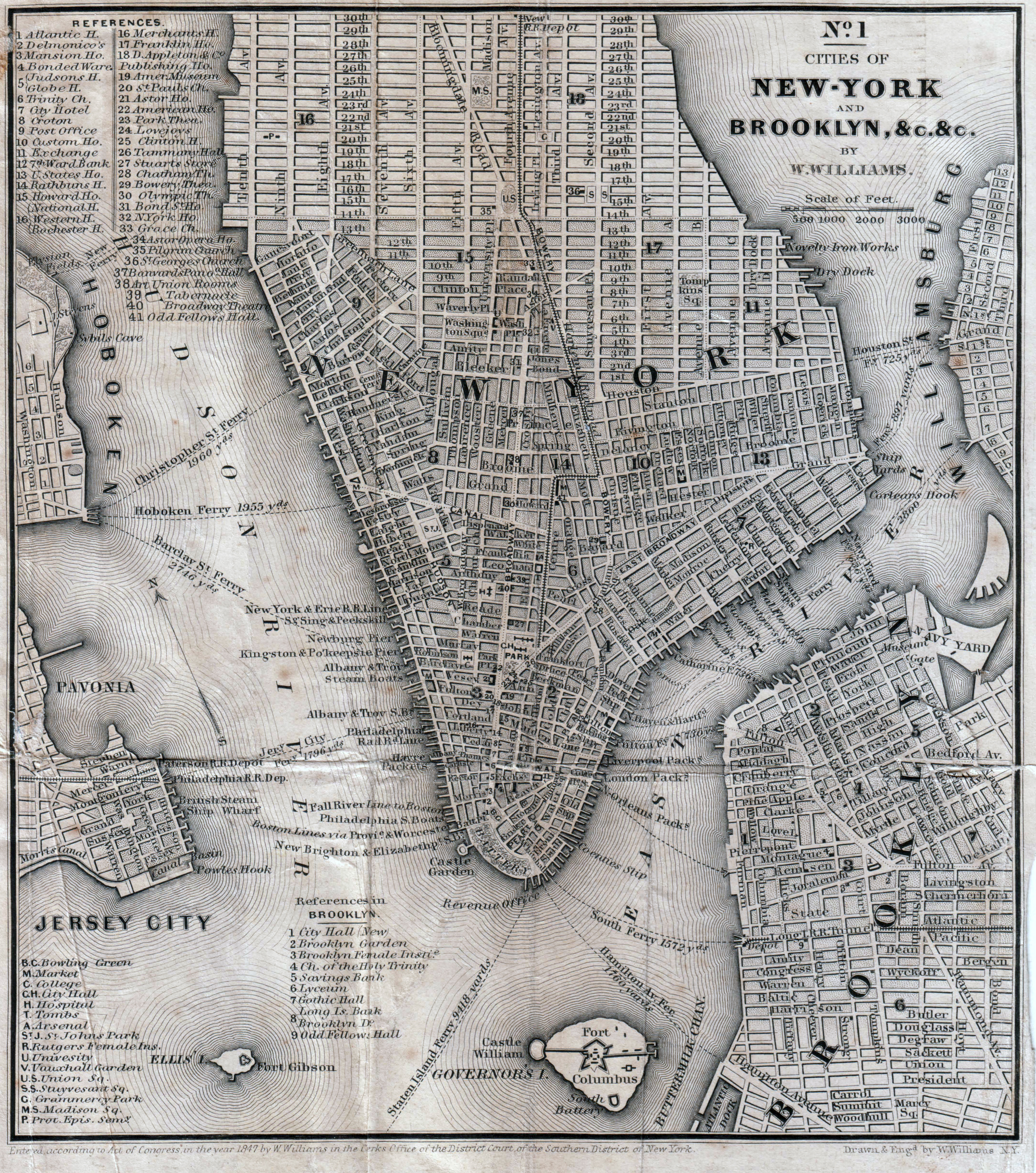

Downtown Manhattan Map (1848)

The P&LE opened for service in 1879 to Youngstown, Ohio and was quickly eyed by the LS&MS. At around the same time the NYC&HR pushed into the coalfields of central Pennsylvania via the Beech Creek Railroad and ownership of the the Fall Brook Coal Company.

The Central would eventually operate an "inside gateway" through this region; branching from Lyons, New York these lines passed southward through Geneva and extended to Williamsport, Pennsylvania before turning westward to Curwensville and finally terminating back at Ashtabula, Ohio.

New York Central F7A #1681, F2A #1605, and F7A #1817 with a caboose hop at 113th and Lake Streets in Hammond, Indiana in February, 1963. Rick Burn photo.

New York Central F7A #1681, F2A #1605, and F7A #1817 with a caboose hop at 113th and Lake Streets in Hammond, Indiana in February, 1963. Rick Burn photo.The Central controlled two other notable coal roads, one in Ohio and the other in Illinois. According to Donald Mills, Jr.'s book, "The Kanawha & Michigan Railroad: Bridge Line To The Lakes," the Toledo & Ohio Central began as the Atlantic & Lake Erie incorporated on June 12, 1869 to tap the coal fields of southern Ohio running from Pomeroy along the Ohio River to Toledo.

Like most such projects it struggled financially and went through several name changes but by the early 1890s had largely been completed as intended. The T&OC even reached into the heart of West Virginia by acquiring the Kanawha & Michigan which extended from Point Pleasant to Dickinson (southeast of Charleston).

These lines, collectively, moved a great deal of coal under Central's ownership but also blossomed into a hearty petrochemical business as numerous plants sprang up within the Mountain State's Kanawha Valley (this business remains here even today).

The Cairo & Vincennes Railroad (C&V) was an Illinois system organized on March 6, 1867. It was completed between its namesake cities, 157 miles, on December 26, 1872 and contained one tunnel of about 800 feet located at the small community of Tunnel Hill.

The C&V would come under the control of the newly created Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St Louis in 1890. Soon after it opened the C&V route offered lucrative volumes of black diamonds as rich veins of high-sulfur, bituminous coal were located in the southern region of Illinois.

According to Joseph Schwieterman’s, "When The Railroad Leaves Town: Eastern United States," short branches were also constructed from the main line to serve numerous mines owned by Big Creek Coal, Harrisburg Coal, O’Gara Coal and other companies.

Coal remained the dominant source of freight throughout the years and the route grew in importance when the CCC&StL pushed its tracks north of Danville, Illinois to East Chicago through subsidiary Chicago, Indiana & Southern.

The new line opened on January 21, 1906 and provided direct service between Chicago and Cairo earning it the nickname, the "Egyptian Line," since its southern terminus was spelled like the ancient capital of Egypt.

Electrified Lines

While NYC's electrification projects were not nearly as prolific as rival Pennsylvania’s, the railroad did have expansive operations in and around the New York City region as well as short segments in Cleveland and Detroit.

Also, all of the Central’s electrified lines were built to satisfy particular city ordinances, most notably in New York, and the railroad did not bother electrifying large portions of its main lines like the Pennsy.

However, despite this, the Central used its electrified operations very effectively and efficiently, particularly through the use of under-running third-rail, an application that uses an additional (and slightly elevated) rail where “shoes” on locomotives pick up electricity. Third-rail also allows for a “cleaner” right-of-way and less maintenance than traditional overhead catenary.

It's the early Penn Central/Amtrak era as a New York Central "P Motor" hustles northbound at Hastings-on-Hudson, New York with Amtrak's train #75 in May, 1971. Henry Butz photo.

It's the early Penn Central/Amtrak era as a New York Central "P Motor" hustles northbound at Hastings-on-Hudson, New York with Amtrak's train #75 in May, 1971. Henry Butz photo.The railroad's inner-city electrified lines initially began as an idea in the late 19th century to solve the ever-growing congestion issue of passenger traffic using its main line into downtown Manhattan to reach the railroad’s Grand Central Depot.

To solve this increasing problem the NYC decided to construct a series of underground and reach Manhattan via a much larger, and brand new terminal. Due to the length of the tunnels the NYC realized that the only practical type of motive power to use was electrics.

However, the development of this project was swiftly expedited after a New York Central passenger train collided with a New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad suburban train in January of 1902 in New York City (because of a smoke-obscured signal), many cities began passing ordinances banning steam from their city limits due to their inherent health and safety risks.

Soon after this tragedy the Central began electrifying its lines in and around New York, which first began operations on September 20, 1906 (the railroad was required by the new city ordinance to discontinue use of steam locomotives by July 1, 1908).

In total, the New York Central Railroad would go on to electrify its Hudson Division between the later built Grand Central Terminal and Harmon (now Croton-Harmon) as well as its Harlem Division.

When the New York Central electrification project began the railroad decided on a 660-volt, direct current (DC) system employing third-rail, similar in nature to what the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had used for its Baltimore Belt Railroad project a decade earlier (the NYC looked to the B&O’s project for guidance when constructing its own electrified lines).

For power the Central began with a 1-D-1 electric locomotive design built by General Electric; originally classified as Class L it was eventually changed to an S-1 class and the only one ever rostered by the railroad.

A rather short and stubby locomotive what it lacked in length it more than made up for in power featuring a constant rating of 2,200 hp with short bursts for acceleration as high as 3,000 hp.

Numbered 6000 the locomotive was later renumbered to 100 and was still used in daily operation through the 1960s, mostly for yard work (the locomotive has also been preserved but is not on public display).

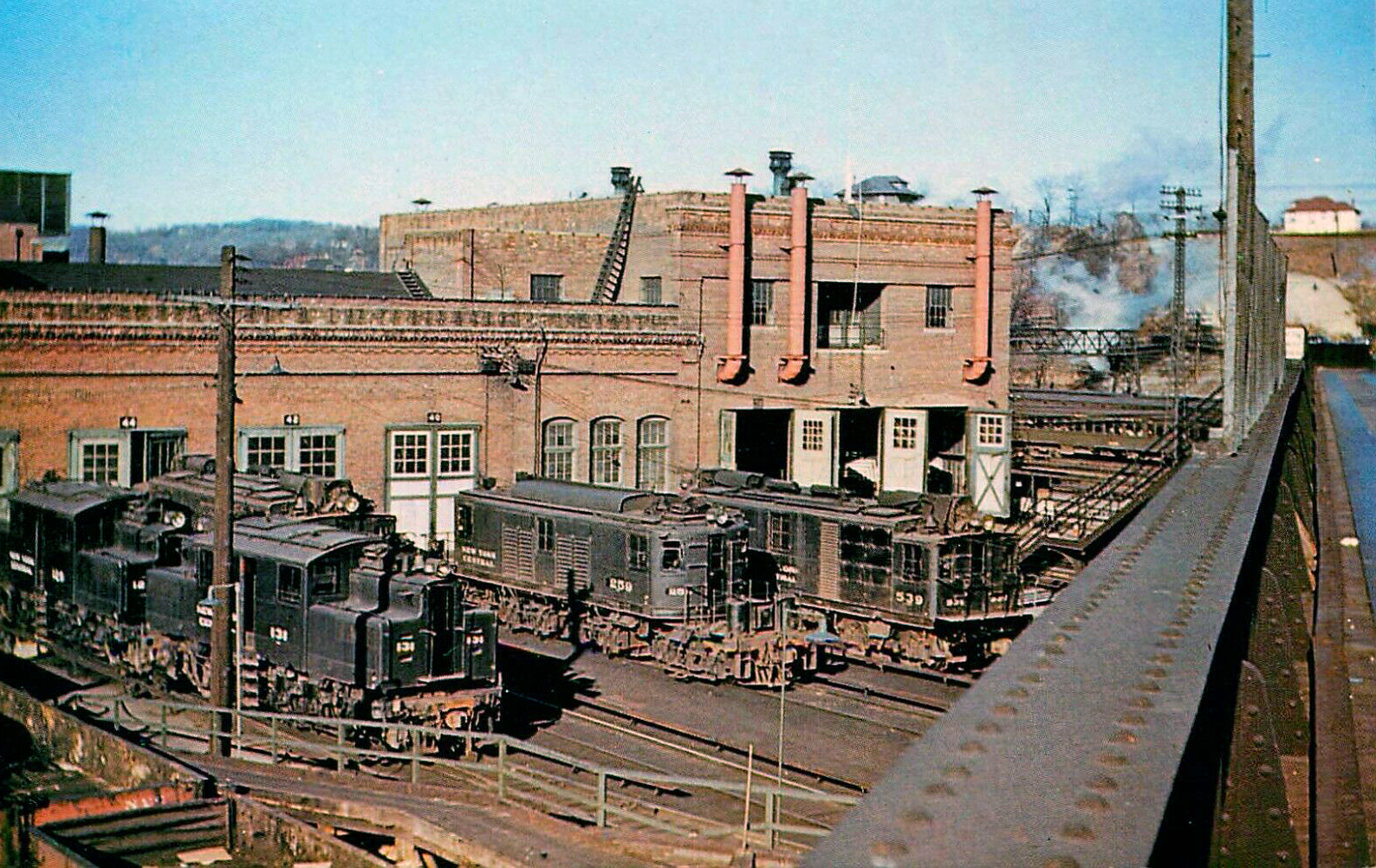

A view of New York Central's electric maintenance facility at Harmon, New York as seen in December, 1949. In the foreground is S Motors #131 and #120; next is T Motor #259 followed by tri-power unit #539. Tucked away behind the S Motors is likely another tri-power unit. William Rinn photo.

A view of New York Central's electric maintenance facility at Harmon, New York as seen in December, 1949. In the foreground is S Motors #131 and #120; next is T Motor #259 followed by tri-power unit #539. Tucked away behind the S Motors is likely another tri-power unit. William Rinn photo.In all the NYC would own three classes of S electrics, the aforementioned S-1 and later models, S-2 and S-3. The railroad would roster a total of 34 S-2s, and 12 S-3s, all purchased during the first decade of the 20th century.

Of note, these locomotives gained their designation as S-motors when they were rebuilt with a 2-D-2 wheel arrangement after another serious accident killed 23 people involving S-2s with a 1-D-1 arrangement (the added axle to the front and rear helped the locomotives steer better into curves, which was the cause of the second deadly accident, a locomotive jumping the track).

Rather simple designs, NYC’s S locomotives featured gearless traction motors and were eventually all relegated to yard work since their small number of axles put more weight on the rails, thus causing increased wear.

The Central’s first purchase of upgraded motors occurred in 1913 when it began taking delivery of an end-cab design with a B-B+B-B wheel arrangement. Designated as T-motors, their all-powered axles allowed for increased horsepower yet with more axles on the rails, less wear on the infrastructure.

Because of this the Ts were often used in regular passenger train service and hauling the NYC’s premier named trains to and from Grand Central Terminal.

Thus, T-motors were probably the most often seen New York Central Railroad electrics by the public as they could typically be spotted out on the open main lines in and around New York City.

The T-motors remained in operation all of the way until the Penn Central merger when they were bumped from service first by the railroad's Class P electrics and later all of the the New York Central's motors were retired in favor of New Haven Railroad’s FL9s.

New York Central F7s at Collinwood, Ohio (Cleveland), circa 1965. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

New York Central F7s at Collinwood, Ohio (Cleveland), circa 1965. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Other NYC electric locomotives included Class Qs, Class Rs and Class Ps (as mentioned above). The Qs and Rs were of GE’s steeple-cab design and featured a B-B wheel arrangement (similar in nature to those used by the B&O).

Purchased in the 1920s they were predominantly used on the electrified lines of the Detroit River Tunnel. The Class Ps were used around Cleveland Union Terminal and were originally designated as Class P-1a.

They featured a 2-C+C-2 wheel arrangement and after CUT electrified operations were discontinued in the 1950s were transferred to GCT, reequipped for third-rail operation and dubbed P-2a and P-2b.

A New York Central publicity photo featuring 4-8-2 "Mohawk" #2793 ahead of covered hoppers at Churchville, New York during June of 1946. Ed Nowak photo.

A New York Central publicity photo featuring 4-8-2 "Mohawk" #2793 ahead of covered hoppers at Churchville, New York during June of 1946. Ed Nowak photo.One of the final electric locomotive types purchased by the New York Central was the R-2 class. They featured the now-common C-C wheel arrangement used and diesel locomotives, and nose-suspended traction motors, far more advanced than any other type of electric the railroad had previously purchased.

Interestingly, however, they lived out most of their lives on the NYC in secluded isolation, being used in freight service on the railroad’s West Side electrified lines. Today, while several of the S class motors have been preserved none are on public display.

However, while this is the case, both Amtrak and Metro North continue to use many of the railroad’s electrified lines today for commuter and intercity services, including service to Grand Central Terminal (although the station itself only serves local commuters).

Thanks to Joe Klapkowski for help with this information.

New York Central GP7s, #5642 and #5645, at Bellwood Street and Paol Avenue in Bellwood, Illinois in June, 1963. Rick Burn photo.

New York Central GP7s, #5642 and #5645, at Bellwood Street and Paol Avenue in Bellwood, Illinois in June, 1963. Rick Burn photo.During the last few decades of the 19th century the New York Central was expanding in virtually every direction; many projects, extensions, and maneuverings were happening all at the same time. Such was the case with the road's reach into northern New York.

Between these additions and its Boston & Albany subsidiary the Central was the only major trunk line to also serve the heart of New England.

Through yet more business savvy tactics the railroad leased the much-sought Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg in 1891, a system that dated back to an 1861 merger between the Watertown & Rome and Potsdam & Watertown Railroads.

The RW&O ran from Rome to Norwood via Watertown and later extended branches to Ogdensburg, along the St. Lawrence River, and Oswego situated on the shores of Lake Ontario.

The RW&O had reached as far as Massena, via Norwood, before the NYC&HR gained controlled. An extension to Montreal, Quebec came by way of another small road, the Mohawk & Malone, leased to the NYC in 1902

A pair of recently delivered New York Central E8A's sit on display at the Railway Supply Manufacturers' Association trade show in Atlantic City, New Jersey in late June of 1953. Among the other equipment at this event was Fairbanks Morse's new H24-66 "Train Master" demonstrators.

A pair of recently delivered New York Central E8A's sit on display at the Railway Supply Manufacturers' Association trade show in Atlantic City, New Jersey in late June of 1953. Among the other equipment at this event was Fairbanks Morse's new H24-66 "Train Master" demonstrators.No other railroad dominated the New York City region like the Central. At the end of the 19th century it had further cemented its power here by acquiring two additional properties, the New York & Northern and the New York, Buffalo & West Shore.

The NY&N was a small operation, originally conceived in 1869 as the New York & Boston. It eventually opened 52 miles from 155th Street/Sedgwick Avenue in New York City to Brewster during the spring of 1881.

The road was not particularly profitable and fell into receivership, acquired by J.P. Morgan and renamed as the New York & Putnam Railroad in 1894 upon which time it came under the Central's control.

The NYC&HR's interest was largely to keep potential rivals at bay as the line wasn't even terribly successful under its oversight. The Putnam Division (or "The Put"), as it was known, served largely as a commuter route and was slowly abandoned after the 1960s.

The NYB&WS, however, was a much more robust operation and for many years was not under the Central's control. It proved a serious threat to the Vanderbilt-road, eventually opening a competitive route along the west shore of the Hudson River from Weehawken/Jersey City to Buffalo via Albany by 1884.

The line had been heavily funded by Central's arch-rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and it appeared the NYC&HR would lose hold of its near-monopoly on New York City.

In the cutthroat nature of railroading during this era the NYC&HR began building its famous South Pennsylvania Railroad to offer a better routing over the PRR's superb Philadelphia - Pittsburgh main line.

With Morgan as an intermediary the two sides eventually settled the dispute with each acquiring the other's holdings in these systems.

The Central took over the NYB&WS in 1885, renaming it as the West Shore Railroad. Interestingly, the old South Pennsylvania was eventually sold to the state with sections becoming part of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound New York Central freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at the once very busy interlocking in North Judson, Indiana on November 27, 1966. Rick Burn photo.

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound New York Central freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at the once very busy interlocking in North Judson, Indiana on November 27, 1966. Rick Burn photo.20th Century Operations

By the turn of the 20th century the NYC&HR was largely in place. To streamline the organization, all of the properties except for the Boston & Albany, Michigan Central, and Big Four were merged on December 22, 1914 into the second New York Central Railroad.

Although not quite as large as rival Pennsylvania the NYC was a formidable competitor and recognized as one of the country's elite railroads. It operated a network of more than 10,000 miles and served nine states as well as southern Ontario and Montreal, Quebec.

It upgraded most of its lines around New York with third-rail, electrification for safer and more efficient operations (it also utilized electrification around Cleveland and Buffalo/Niagara Falls), expanded its "Water Level Route" to four tracks from New York to Buffalo, utilized double-tracking on most key routes, and maintained a robust passenger/commuter fleet.

The NYC weathered the onslaught of traffic during World War I and the government's mismanagement under the United States Railway Association (USRA) at that time. It also managed to escape the Great Depression without falling into bankruptcy although the system had fallen onto hard times.

System Map (1940)

While the Central had a large and exquisite passenger fleet its flagship was without doubt the New York-Chicago 20th Century Limited. Arguably the most regal passenger train ever created the Limited was adorned in grays, silvers, and whites while ushering in the Art Deco era of interior design.

It was streamlined in 1938 (and one could only hope to find a seat on the Limited, let alone afford a ticket!) and powered by handsome 4-6-4 (J-3a) Hudsons, stylized by Henry Dreyfuss.

The New York Central System is remembered for many things but perhaps the railroad’s crowning achievement was its Grand Central Terminal located in downtown New York City.

Opened in 1913, three years after the Pennsy opened Penn Station, GCT replaced the earlier Grand Central Station. The new terminal held an impressive 48-track yard below ground to accommodate both commuter and long-distance services. It was beautifully adorned inside and out (as only the Vanderbilt family would allow), and served NYC trains until the end.

Today, it thankfully still stands and not only continues to haul commuters but is also a National Historic Landmark and one of New York’s popular tourist attractions.

The Central rebounded well during World War II and felt so good about its future prospects that it ordered 420 new lightweight, streamlined cars in 1945 to overhaul its passenger fleet. This was in addition to 300 cars it had already ordered only a year earlier.

Mr. Schafer and Mr. Solomon point out in their book that the combined purchase (720 cars) was the largest single order, ever, for any American railroad. Alas, as the industry soon realized the wartime traffic boon was but a mirage. By the early 1950s, as traffic sank the Central was nearly bankrupt and its rival was in far worse shape.

In a poignant sign of the times, the PRR lost money for the first time ever in 1946 and continued to spiral through the following decade.

The NYC's fortunes soon turned when Alfred Perlman was elected president. Under his guidance the railroad began an aggressive campaign to upgrade the property, modernize the network, and cut costs as effectively as possible.

In doing so, he completely dieselized the locomotive fleet, built new classification yards, and introduced new innovative marketing schemes such as Flexi-Van service (the trains themselves were known as Super Vans), an idea far ahead of its time, which was the first successful application of Container-On-Flat-Car service (or COFC).

Penn Central

According to Rush Loving, Jr.'s book, "The Men Who Loved Trains," Perlman and the railroad's culture was laid back where ideas and open discussion freely flowed to solve problems, which greatly aided in getting the company back onto its feet.

Still, despite Perlman's efforts the NYC's future remained uncertain as an independent carrier. The merger movement was stirring as systems attempted to cut costs and streamline operations in the face of declining traffic and strict government regulations.

The Norfolk & Western had acquired rival Virginian in 1959, the Erie/Delaware, Lackawanna & Western merged in 1960 to form Erie Lackawanna, and Chesapeake & Ohio was eyeing the Baltimore & Ohio.

It was during this time that the longtime rivals began exploring the idea of merger, despite Perlman’s protests to find a more logical partner.

The NYC looked long and hard but could find no serious interests and it lost out on a bid for the B&O to the C&O in the early 1960s (perhaps the best fit for the NYC, this southern road would have provided new marketing opportunities).

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound NYC freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at North Judson, IN; November 27, 1966. Rick Burn photo.

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound NYC freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at North Judson, IN; November 27, 1966. Rick Burn photo.In the end and despite a long search it was eventually decided a merger with the PRR was the only option. Surprisingly the ICC approved the union that virtually gave the ill-fated Penn Central Transportation Company a monopoly in the Northeast.

The new conglomerate was born on February 1, 1968. On merger day chaos ensued and the new railroad literally fell apart right from the start. To make matters worse the NYC and PRR could not have had more opposite corporate cultures.

The NYC and PRR folks did not care for one another, magnified by the latter's arrogance. The Pennsy had always maintained a militaristic structure.

Their corporate attitude was one of adherence and knowing one's place in the chain of command; it was extremely strict, new ideas were shunned, and orders came down from higher ups.

Mr. Loving points out in his book that no other railroad within the industry was disliked as much as the PRR. Naturally, as these two teams failed to work together, pure hell and pandemonium resulted.

Passenger Trains

Chicagoan: (New York - Cleveland - Chicago)

Chicago Mercury: (Chicago - Detroit)

Cincinnati Mercury: (Cleveland - Cincinnati)

Cleveland Mercury: (Detroit - Cleveland)

Detroit Mercury: (Cleveland - Detroit)

Knickerbocker: (New York - St. Louis)

The Michigan: (Chicago - Detroit)

Motor City Special: (Chicago - Detroit)

Twilight Limited: (Chicago - Detroit)

The PC was losing over $1 million a day and trains were becoming lost throughout the system, as personnel were not properly trained on how to dispatch their trains.

In addition, because the merger had been so hastily planned there had never been a true system established to route and monitor movements.

As the red ink became an unstoppable flash flood maintenance was deferred and derailments became the norm with large sections of main line reduced to 10 mph slow orders.

After only two years of operations and financial assistance completely gone, the destitute Penn Central officially declared bankruptcy on June 21, 1970 shocking the financial world.

When PC was formed the Pennsylvania had technically acquired the Central and despite its financial problems at the time the PRR maintained a stellar credit rating and view throughout Wall Street. It was a gold-plated corporation with a long history of success. Nobody, especially the PRR folks, believed it could fail.

The result of the bankruptcy was also a ripple effect throughout the entire Northeast as other teetering railroads, which depended on the PC to interchange traffic, struggled to keep their freight moving. It became so bad by the mid-1970s that the Penn Central was facing total shutdown if financial assistance, any means of help at all, did not arrive.

Diesel Roster

Steam Roster

More Reading

Conrail

Realizing the severity of the situation the federal government stepped in and setup the Consolidated Rail Corporation, which comprised the skeletons of several bankrupt Northeastern carriers, and began operations on April 1, 1976.

With federal backing Conrail began to slowly pull out of the red ink (it took many years) and by the 1980s was a profitable railroad after thousands of miles of excess trackage (and sometimes perhaps not so excess when compared to today’s boom of the industry) was abandoned and/or upgraded.

Today, even Conrail is no longer with us having been split up amongst CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern in 1999, with CSX taking much of the NYC while NS got a good chunk of the Pennsy.

In any event many parts of the railroad continue to serve an important role in moving goods (and people) from eastern markets to the Midwest and vice versa (such as its main line Water Level Route).

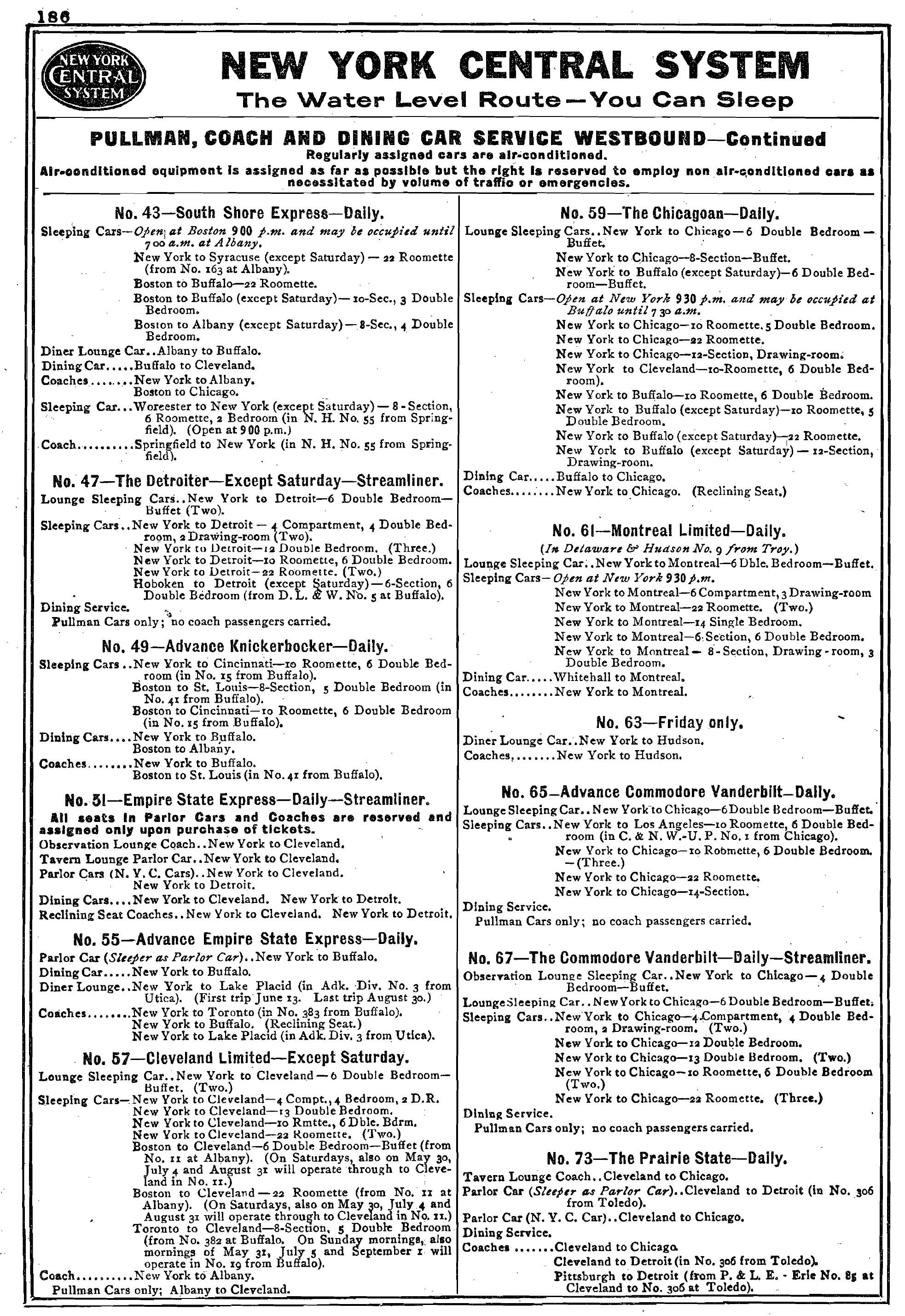

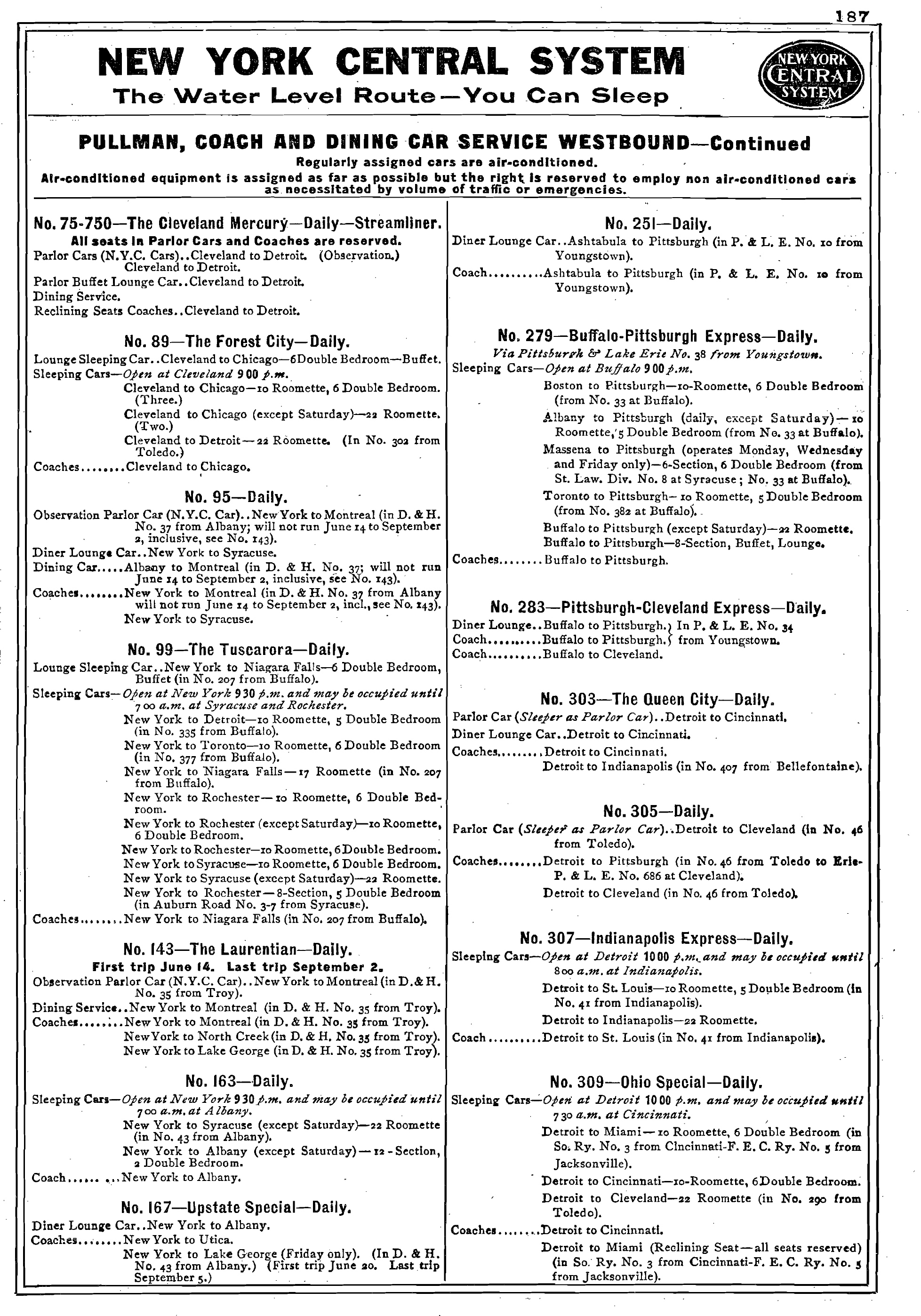

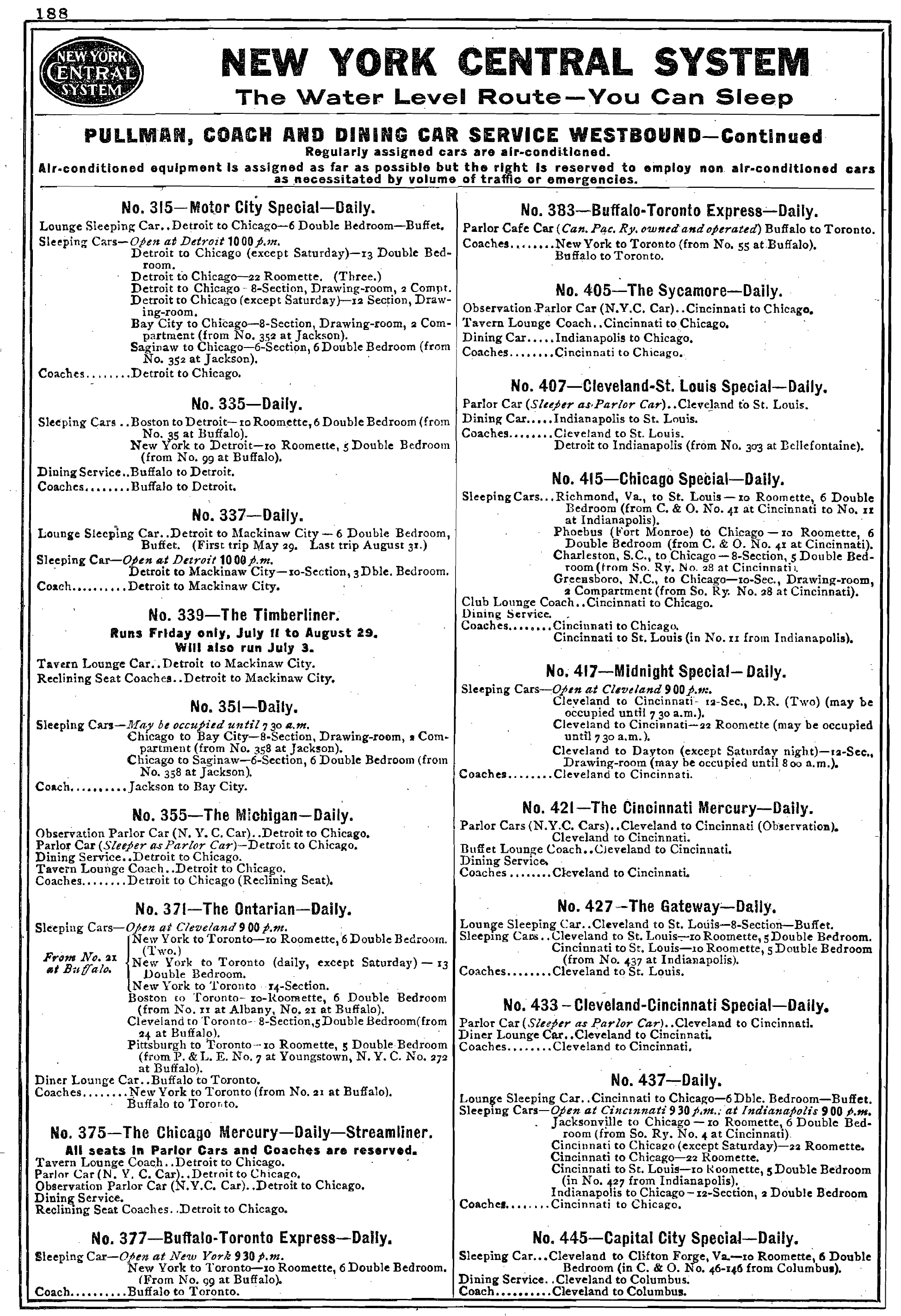

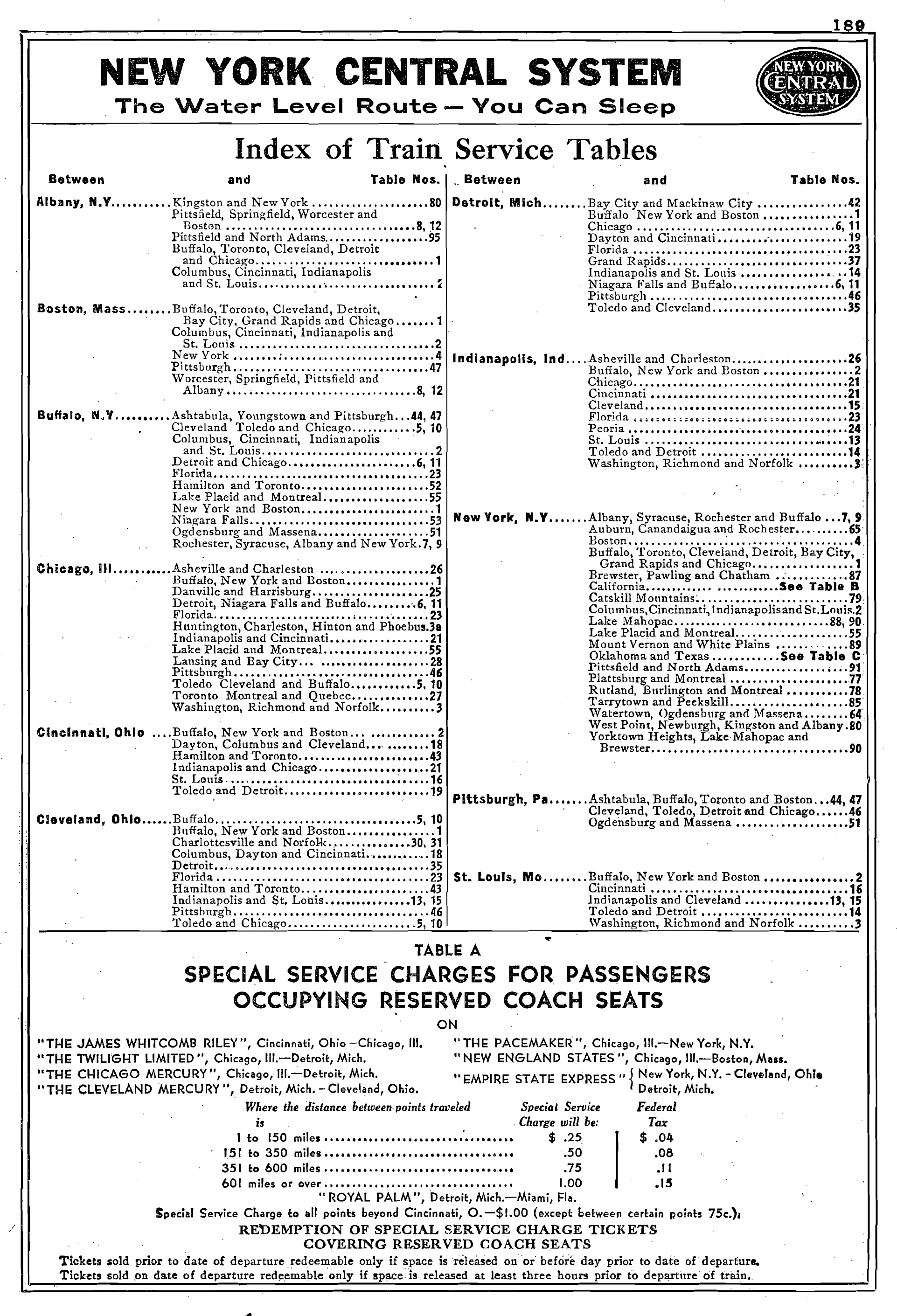

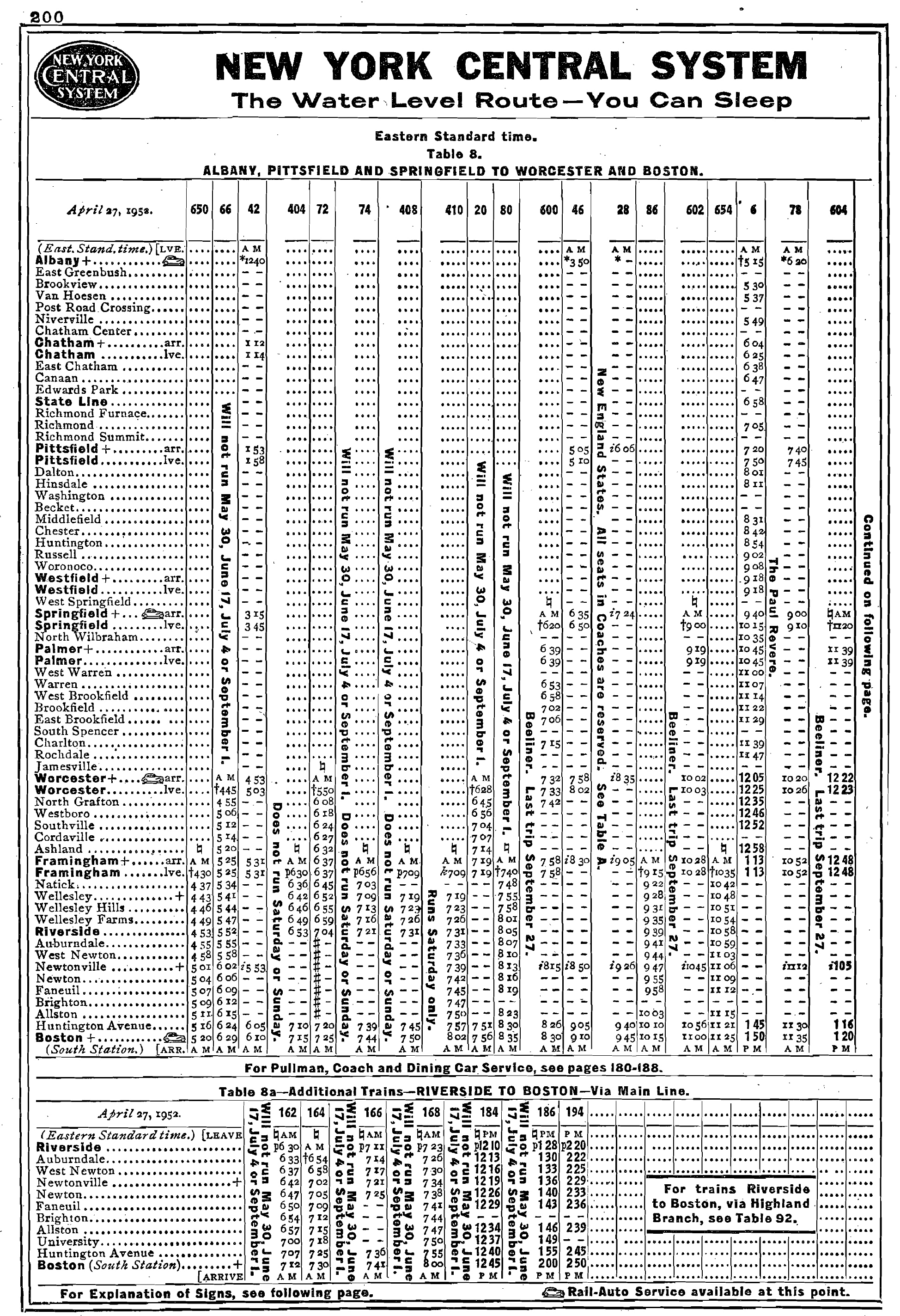

Public Timetables (1952)

Recent Articles

-

Building A T1 Again: The PRR 5550 Project

Feb 15, 26 06:10 PM

Today, a nonprofit group, the PRR T1 Steam Locomotive Trust, is doing something that would have sounded impossible for decades: building a brand-new T1 from the ground up. -

PRR T1 No. 5550’s Cylinders Nearing Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:53 PM

According to a project update circulated late last year, fabrication work on 5550’s cylinders has advanced to the point where they are now “nearing completion,” with the Trust reporting cylinder work… -

Santa Fe 3415's Rebuild Nears Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:14 PM

One of the Midwest’s most recognizable operating steam locomotives is edging closer to the day it can lead excursions again. -

Ohio Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:59 AM

Among Lebanon Mason & Monroe Railroad's easiest “yes” experiences for families is the Family Pizza Train—a relaxed, 90-minute ride where dinner is served right at your seat, with the countryside slidi… -

Wisconsin Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:57 AM

Among Wisconsin Great Northern's lineup, one trip stands out as a simple, crowd-pleasing “starter” ride for kids and first-timers: the Family Pizza Train—two hours of Northwoods views, a stop on a tal… -

Illinois "Pizza" Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:55 AM

For both residents and visitors looking to indulge in pizza while enjoying the state's picturesque landscapes, the concept of pizza train rides offers a uniquely delightful experience. -

Tennessee's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:50 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:48 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Staunton!

Feb 15, 26 10:46 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a classic scenic train ride with a genuinely satisfying meal—served at your table while the countryside rolls by—the Virginia Scenic Railway was built for you. -

New Hampshire's Dinner Train Rides In N. Conway

Feb 15, 26 10:45 AM

Tucked into the heart of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Valley, the Conway Scenic Railroad is one of New England’s most beloved heritage railways. -

Union Pacific 4014 Begins Coast-To-Coast Tour

Feb 15, 26 12:30 AM

Union Pacific’s legendary 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 is scheduled to return to the main line in a big way this spring, kicking off the railroad’s first-ever coast-to-coast steam tour as part of a broa… -

Amtrak Introduces The Cascades Airo Trainset

Feb 15, 26 12:11 AM

Amtrak pulled the curtain back this month on the first trainset in its forthcoming Airo fleet, using Union Station as a stage to preview what the railroad says is a major step forward in comfort, acce… -

Nevada Northern Railway 2-8-0 81 Returns

Feb 14, 26 11:54 PM

The Nevada Northern Railway Museum has successfully fired its Baldwin-built 2-8-0 No. 81 after a lengthy outage and intensive mechanical work, a major milestone that sets the stage for the locomotive… -

Metrolink F59PH 851 Preserved In Fullerton, CA

Feb 14, 26 11:41 PM

Metrolink has donated locomotive No. 851—its first rostered unit—to the Fullerton Train Museum, where it will be displayed and interpreted as a cornerstone artifact from the region’s modern passenger… -

Oregon's Dinner Train Rides Near Mt. Hood!

Feb 14, 26 09:16 AM

The Mt. Hood Railroad is the moving part of that postcard—a century-old short line that began as a working railroad. -

Maryland's Dinner Train Rides At WMSR!

Feb 14, 26 09:15 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) has become one of the Mid-Atlantic’s signature heritage operations—equal parts mountain railroad, living museum, and “special-occasion” night out. -

Colorado Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:13 AM

If there’s one weekend (or two) at the Colorado Railroad Museum that captures that “living history” spirit better than almost anything else, it’s Wild West Days. -

South Dakota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:11 AM

While the 1880 Train's regular runs are a treat in any season, the Oktoberfest Express adds an extra layer of fun: German-inspired food, seasonal beer, and live polka set against the sound and spectac… -

Kentucky Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:10 AM

One of KRM’s most crowd-pleasing themed events is “The Outlaw Express,” a Wild West train robbery ride built around family-friendly entertainment and a good cause. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:08 AM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Indiana "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:06 AM

Indiana offers a unique opportunity to experience the thrill of the Wild West through its captivating train rides. -

B&O Observation "Washington" Cosmetically Restored

Feb 14, 26 12:25 AM

Visitors to the B&O Railroad Museum will soon be able to step into a freshly revived slice of postwar rail luxury: Baltimore & Ohio No. 3316, the observation-tavern car Washington. -

Southern 2-8-2 4501 Returns To Classic Green

Feb 14, 26 12:24 AM

Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum officials announced that Southern Railway steam locomotive No. 4501—the museum’s flagship 2-8-2 Mikado—will reappear from its annual inspection wearing the classic Sou… -

Illinois Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:04 PM

Among Illinois's scenic train rides, one of the most unique and captivating experiences is the murder mystery excursion. -

Vermont ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:00 PM

There are currently murder mystery dinner trains offered in Vermont but until recently the Champlain Valley Dinner Train offered such a trip! -

Missouri Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 11:47 AM

Among the Iron Mountain Railway's warm-weather offerings, the Ice Cream Express stands out as a perfect “easy yes” outing: a short road trip, a real train ride, and a built-in treat that turns the who… -

Florida "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:53 AM

This article delves into wild west rides throughout Florida, the historical context surrounding them, and their undeniable charm. -

West Virginia "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:49 AM

While D&GV is known for several different excursions across the region, one of the most entertaining rides on its calendar is the Greenbrier Express Wild West Special. -

Alabama "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:47 AM

Although Alabama isn't the traditional setting for Wild West tales, the state provides its own flavor of historic rail adventures that draw enthusiasts year-round. -

Michigan "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:46 AM

While the term "wild west" often conjures up images of dusty plains and expansive deserts, Michigan offers its own unique take on this thrilling period of history. -

Grand Trunk Western 4-6-2 No. 5629

Feb 13, 26 12:10 AM

Included here is a detailed look at 5629’s build date and design, key specifications, revenue career on the Grand Trunk Western, its surprisingly active excursion life under private ownership, and its… -

New York Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:19 PM

New York is home to several Easter-themed train rides including the Adirondack Railroad, Catskill Mountain Railroad, and a few others! -

Missouri Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:13 PM

The beautiful state of Missouri is home to a handful of heritage railroads although only one provides an Easter-themed train ride. Learn more about this event here. -

Arizona's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:05 PM

Let's delve into the captivating world of Arizona's Wild West train adventures, currently offered at the popular Grand Canyon Railway. -

Missouri's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:49 PM

In Missouri, a state rich in history and natural beauty, you can experience the thrill of a bygone era through the scenic and immersive Wild West train rides. -

Maine's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:42 PM

Tea trains aboard the historic WW&F Railway Museum promises to transport you not just through the picturesque landscapes of Maine, but also back to a simpler time. -

Pennsylvania Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:09 PM

In this article, we explore some of the most enchanting tea train rides in Pennsylvania, currently offered at the historic Strasburg Rail Road. -

Nevada St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 11:39 AM

Today, restored segments of the “Queen of the Short Lines” host scenic excursions and special events that blend living history with pure entertainment—none more delightfully suspenseful than the Emera… -

Minnesota Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 10:22 AM

Among MTM’s most family-friendly excursions is a summertime classic: the Dresser Ice Cream Train (often listed as the Osceola/Dresser Ice Cream Train). -

Wisconsin's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:54 PM

Through a unique blend of interactive entertainment and historical reverence, Wisconsin offers a captivating glimpse into the past with its Wild West train rides. -

Georgia's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:44 PM

Nestled within its lush hills and historic towns, the Peach State offers unforgettable train rides that channel the spirit of the Wild West. -

North Carolina's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:36 PM

North Carolina, a state known for its diverse landscapes ranging from serene beaches to majestic mountains, offers a unique blend of history and adventure through its Wild West train rides. -

South Carolina's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:16 PM

There is only location in the Palmetto State offering a true dinner train experience can be found at the South Carolina Railroad Museum. Learn more here. -

Rhode Island's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:08 PM

Despite its small size, Rhode Island is home to one popular dinner train experience where guests can enjoy the breathtaking views of Aquidneck Island. -

New York Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:56 PM

Tea train rides provide not only a picturesque journey through some of New York's most scenic landscapes but also present travelers with a delightful opportunity to indulge in an assortment of teas. -

California Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:37 PM

In California you can enjoy a quiet tea train experience aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train, which offers an afternoon tea service. -

Tennessee Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:19 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride.