Railroads In The 1800s (1840s): History, Photos, Timeline

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

As 1840 dawned in the United States, railroads remained largely novelty. Watercraft were still the most efficient means of transportation, aided in part by numerous canals (notably the Erie Canal and Pennsylvania's Main Line of Public Works) either in full operation or under construction at that time.

However, having already proved their advantage in speed and year-round operation, railroads were here to stay.

As John Stover points out in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," in 1840 the U.S. contained just under 3,000 miles of track. This number would more than triple by 1850 (9,000+).

Much of it was concentrated in the Northeast/New England although some disconnected lines had opened in the Southeast and as far west as Illinois.

One of the decade's most significant developments was the Pennsylvania Railroad's chartering in 1846, formed by the state legislature to maintain Philadelphia's leverage as a major port city.

History

By 1850 railroads had blossomed into a unified matrix with lines linking the east coast and Midwest.

The industry's growth led to a significant (and important) auxiliary network of car builders, locomotive manufacturers, and related businesses. In this section we will look briefly at how railroads continued to expand during the 1840s.

Photos

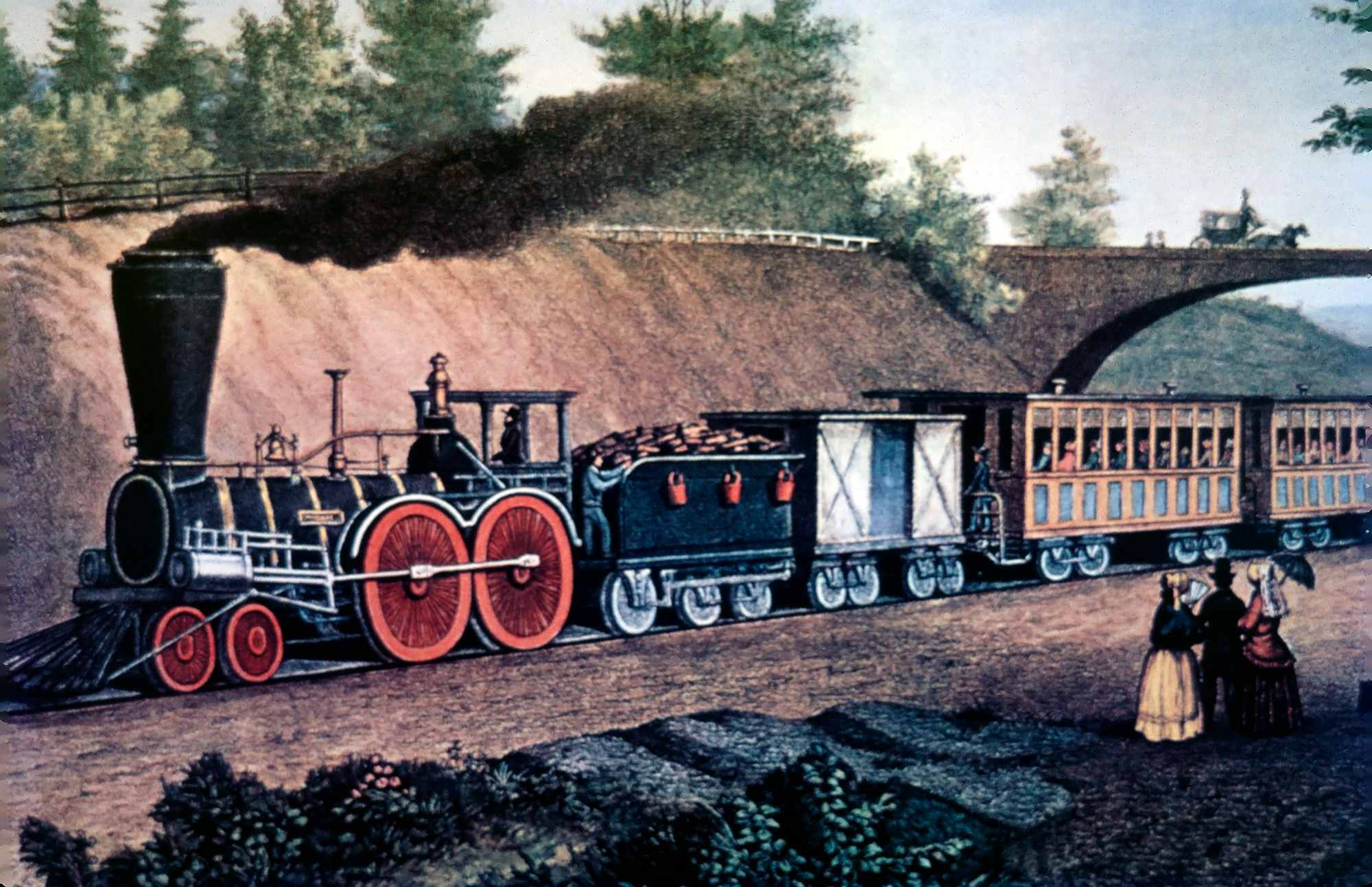

"The Express Train." This was a lithograph by Nathaniel Currier completed in 1840 featuring railroad operations as they would have appeared at that time. Note the early 4-4-0 locomotive and passenger coaches. American-Rails.com collection.

"The Express Train." This was a lithograph by Nathaniel Currier completed in 1840 featuring railroad operations as they would have appeared at that time. Note the early 4-4-0 locomotive and passenger coaches. American-Rails.com collection.Establishing A Network

While the late 1820's and 1830's are widely understood as the founding era of American railroads, the 1840's were also an experimental decade.

During that period engineers and early experts were still under a huge learning curve trying to establish a guide of "best practices" including such things as a standard gauge, efficient coupling system, and car designs.

A few of the more notable advancements occurred in infrastructure. While many early railroads still employed the strap iron rail method (thin sheets of iron fastened to wooden stringers) it was fast being replaced by the solid "T" rail.

In his book, "Railroads Across America: A Celebration Of 150 Years Of Railroading," author and historian Mike Del Vecchio describes the following regarding this revolutionary invention:

"Legend has it that T-rail was invented by Robert Stevens (the son of Colonel John Stevens). Robert was whittling while traveling to England to purchase rails for the Camden & Amboy, and [stumbled onto] the I- or T-shaped form.

The first boatload of T-rails, 550 pieces, each sixteen feet long, three inches tall and weighing thirty-six pounds per yard, arrived in Philadelphia in May, 1831."

Overview

4 Feet, 8 ½ Inches (Standard Gauge) 4 Feet, 3 Inches (Delaware & Hudson) 4 Feet, 10 Inches (Ohio Gauge) 5 Feet 6 Feet | |

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

T-Rail

T-rail held numerous advantages over the strap-iron method:

- Firstly, it was much stronger and could support far greater weight.

- Secondly, it was cheaper (less labor involved)

- Thirdly, could be spiked to a support base, in this case a wooden tie.

Many of the country's first railroads, like the Baltimore & Ohio, used stone ties. The massive blocks were very labor extensive to both transport and install.

By contrast, their wooden counterparts were much lighter while still providing sufficient lateral strength. Finally, ballast (crushed stone) found increasingly widespread use during the 1840s.

Engineers found that it not only reinforced the track but also acted as an excellent drainage system which kept water away from the rails.

With an improving infrastructure and increasing demand, cars and locomotives also needed upgraded. The latter witnessed major advancements through the 1840s and 1850s as America veered away from English designs.

The earliest predecessor of the modern American Locomotive Company was established in Schenectady, New York in 1848 (Schenectady Locomotive Works) while Matthias W. Baldwin, a former jewelry maker, built his first steam locomotive in 1831.

In his book, "Baldwin Locomotives," Brian Solomon notes it was a small design commissioned by Franklin Peale as a display piece for the Philadelphia Museum.

Baldwin based his locomotive on those used in England's famous Rainhill Trials held in October, 1829.

He continued refining his work and even helped assemble British locomotives shipped to America. In 1832 he manufactured his very first, full-scale locomotive for the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad. It carried a 2-2-0 wheel arrangement and was named Old Ironsides.

Closely based on Robert Stephenson's early 2-2-0 Planet design, it was placed into service on November 23rd that year.

As previously mentioned, early American railroads imported almost everything from England (rails, locomotives, cars, etc.) since that country had a well-established manufacturing center and its products were less expensive. This had changed, however, as America's network became better established.

In his authoritative book, "The American Railroad Freight Car," author John H. White, Jr. notes that by 1840 most U.S. railroads had further broken from British influence and abandoned the open freight car concept.

Instead, most were closed (aside from flatcars) in an effort to protect ladding (freight) against weather and, in some cases, vandals.

Two-Axle Trucks

It was becoming clear America would surpass its longtime rival in overall tonnage and mileage. To meet growing demand, American railroads shifted to two-axle trucks by 1840.

As Mr. White notes, they offered more than just increased capacity for freight cars; since many railroads had been built cheaply with, in many cases, sharp grades, stiff curves, light rail, and little or no ballast the extra axles offered greater weight distribution.

Perhaps, though, its greatest attribute was its pivoting, free-swiveling design which enabled a car to easily navigate all types of track conditions.

The first four-axle car was placed into service on the Baltimore & Ohio during the winter of 1830/1831 to ship cords of firewood from outlying forests into Baltimore as home heating fuel.

These experimental cars worked exceedingly well and the B&O eventually rostered some 25 of what were dubbed "Trussell Cars" by 1834.

Shortly thereafter the railroad contracted with J. Rupp and H. Schultz for 110, 24-foot boxcars featuring two-axle trucks.

By 1838 the B&O stated it was upgrading all freight cars with two-axle trucks. The concept quickly caught on throughout the industry and by 1850 few two-axle freight cars remained in service.

Passenger cars remained as rudimentary as their freight hauling counterparts.

In many ways, they had seen even fewer advancements during the ten years following the B&O's inauguration of passenger service (Mount Clare to Carrollton Viaduct) on January 7, 1830.

The first railroads relied on cars inspired by stagecoaches, which provided few accommodations and an even rougher ride.

The modern diner, lounge, sleeper, and other popular services which became commonplace by the late 19th century were still decades away. However, advancements in the standard coach were being made.

Soon after the B&O placed its first Trussell Car into service, the company sought an overhaul of its stagecoach-influenced passenger cars.

In his book, "The American Railroad Passenger Car," author John H. White, Jr. points out that as early as 1828 or 1829 the B&O was visited by Joseph Smith from Philadelphia with a proposal for a rectangular coach of significant length to handle more travelers.

While never actually built it was a radical departure from typical designs.

The idea was later picked up by B&O's treasurer, George Brown, who requested an testbed car based on Smith's idea which would feature double trucks. It was named the Columbus and constructed during the spring of 1831.

Officially placed into service on July 4, 1831 it was initially pulled by horses although steam locomotives had soon taken over these duties by July 13th.

In another first, the B&O also placed the first modern coach into service during 1834. In his excellent book, "The Railroad Passenger Car," author August Mencken notes it was the work of Ross Winans, featuring a center aisle running longitudinally with seating to each side that carried double-trucks.

While only a prototype all future passenger cars were based from this design (incredibly, one such "Winans Car" remained in regular use on the Tioga Railroad until 1883). As the 1850's dawned, strides were being made in seating capacity but also passenger comfort.

The latter was revolutionized by George Pullman during that decade who recognized a market in pampering travelers.

During the 1840s railroads could still be described as rudimentary with little government jurisdiction. As a result, accidents, injuries, and deaths were common.

The lack of federal authority meant railroads could do whatever they pleased and most refused to work together in the name of competition and greed.

Despite these problems, railroads were the fastest way to travel and by 1850 every state east of the Mississippi, except Florida, could boast at least a few miles of track.

In addition, the now widely recognized 4-4-0 wheel arrangement was developed at this time, credited to Henry R. Campbell in 1839. The so-called "American" type became the most commonly used and best recognized locomotive of the 19th century thanks to its combination of power, speed, and reliability.

Pioneering Locomotives

The Camden & Amboy's John Bull, a pioneering locomotive built by Robert Stephenson & Company and entered service in 1831, was later upgraded by C&A engineers with a lead "bogey" truck.

This feature allowed the locomotive to easily negotiate curves and became a common feature for those wheel arrangements used in main line service.

This included the 4-4-0, which was refined into the late 1800s and early 20th century with arrangements like the 2-8-0, 2-6-0, 2-8-2, 4-6-0, and many others. By the 1840s, the seeds of which became the four major eastern trunk lines (Pennsylvania Railroad, New York Central, Baltimore & Ohio, and Erie) were well established.

What transpired in the 1840s led to an even greater explosion of new construction the following decade. Aside from the tripling of mileage further technological improvements allowed trains to reach the Midwest in a mere two days instead of a month at the 19th century's dawning.

The 1850s would witness railroads breaking across the Mississippi River into Texas while plans were being drawn up for a transcontinental route into California.

The book "Railroads In The Days Of Steam" by Albert L. McCready and Lawrence W. Sagle, notes that in 1835 more than 200 railroads were either proposed or under construction with around 1,000 miles in operation. By 1850, 9,022 miles of railroad were in service which constituted an investment of $372 million.

Recent Articles

-

North Carolina's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 10:14 AM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Connecticut's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:59 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

New Mexico's Murder Mystery Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:55 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails. -

Michigan Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:50 AM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Florida Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:45 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards. -

Texas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:43 AM

This article invites you on a metaphorical journey through some of these unique wine tasting train experiences in Texas. -

Nevada Museum Acquires Amtrak F40PHR 315

Mar 02, 26 10:32 PM

The Nevada State Railroad Museum has stated they have acquired Amtrak F40PHR 315 from Western Rail, Inc. where it will be used for static display. -

Virginia Railway Express Surpasses 100 Million Riders

Mar 02, 26 09:42 PM

In October 2025, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) reached one of the most significant milestones in its history, officially carrying its 100 millionth passenger since beginning operations more than… -

Restoration Continues On New Haven RS3 529

Mar 02, 26 11:29 AM

The Railroad Museum of New England's efforts to completely restore New Haven RS3 529 to operating condition as they provide the latest updates on the project. -

American Freedom Train No. 250 Completes FRA Steam Test

Mar 02, 26 10:17 AM

One of the most anticipated steam locomotive restorations in modern preservation reached a major milestone this week as American Freedom Train 4-8-4 No. 250 successfully completed a federally observed… -

Indiana's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 10:00 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Maryland's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:54 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

California's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:46 AM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:42 AM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

New York Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:32 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:30 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

NS Completes 1,000th DC-to-AC Locomotive Conversion

Mar 01, 26 11:26 PM

In October 2025, Norfolk Southern Railway reached one of the most significant mechanical milestones in modern North American railroading, announcing completion of its 1,000th DC-to-AC locomotive conve… -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:11 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

North Carolina Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:09 AM

The springs are typically warm and balmy in the Tarheel State and a few tourist trains here offer Easter-themed train rides. -

Maryland Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:05 AM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:03 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Indiana Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:01 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 09:58 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Metro-North Unveils Veterans Heritage Locomotive

Feb 28, 26 11:02 PM

The Metro-North Railroad marked Veterans Day 2025 with the unveiling of a striking new heritage locomotive honoring the service and sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Pennsylvania's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:46 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Alabama's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:44 AM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Georgia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:43 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:40 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Mexico Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:37 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:35 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

KC Streetcar Ridership Surges With Opening of Main Street Extension

Feb 27, 26 11:24 AM

Kansas City’s investment in modern urban rail transit is already paying dividends, especially following the opening of the Main Street Extension. -

“Auburn Road Special” Excursions To Aid URHS

Feb 27, 26 09:04 AM

The United Railroad Historical Society of New Jersey (URHS) and the Finger Lakes Railway have jointly announced a special series of rare-mileage passenger excursions scheduled for April 18–19, 2026. -

New Jersey Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:53 AM

New Jersey is home to several museums and a few heritage railroads that vividly illustrate its long history with the iron horse. A few host special events for the Easter holiday. -

Washington Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:49 AM

You can find many heritage railroads in Washington State which illustrates its rich history with the iron horse. A few host Easter-themed events each spring. -

South Dakota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:46 AM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:42 AM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Pennsylvania Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:38 AM

Wine tasting trains are a unique and enchanting way to explore the state’s burgeoning wine scene while enjoying a leisurely ride through picturesque landscapes. -

West Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:37 AM

West Virginia, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes and rich history, offers visitors a unique way to explore its rolling hills and picturesque vineyards: wine tasting trains. -

Nebraska Lawmakers Advance UP Tax Incentive Bill

Feb 27, 26 08:31 AM

Nebraska lawmakers are advancing new economic development legislation designed in large part to ensure that Union Pacific Railroad maintains its historic corporate headquarters in Omaha. -

UP And NS Ask FRA To Waive Cab-Signals For Big Boy 4014

Feb 26, 26 01:44 PM

Union Pacific’s famed 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 could see new eastern mileage on Norfolk Southern in 2026—but first, the two railroads are asking federal regulators for help bridging a technology gap… -

Cando Rail & Terminals to Acquire Savage Rail

Feb 26, 26 11:29 AM

Cando Rail & Terminals has signed a definitive agreement to acquire Savage Rail, the U.S. rail-services business of Savage Enterprises LLC. -

Dollywood To Convert Steam Locomotives From Coal To Oil

Feb 26, 26 09:20 AM

Dollywood’s most recognizable moving landmark—the Dollywood Express—will soon look and feel a little different. -

Missouri Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:10 AM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:08 AM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Utah Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:04 AM

Utah, a state widely celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty and dramatic landscapes, is also gaining recognition for an unexpected yet delightful experience: wine tasting trains. -

Vermont Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:02 AM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Amtrak San Joaquins Becomes Gold Runner

Feb 26, 26 08:59 AM

California’s busy state-supported rail link between the Bay Area and the Central Valley entered a new chapter in early November 2025, when the familiar Amtrak San Joaquins name was officially retired. -

Canadian National Marks 30 Years Since Privatization

Feb 25, 26 02:07 PM

Canadian National Railway marked a milestone last fall that helped redefine not only the company, but the modern Canadian freight-rail landscape: 30 years since CN went private. -

Western Rail Coalition: Returning Passenger Trains To Colorado

Feb 25, 26 11:48 AM

Colorado’s passenger-rail conversation is often framed as two separate stories: a Front Range “spine” along I-25, and a harder, longer-term quest to offer real alternatives to the I-70 mountain drive. -

Union Pacific Unveils Full Schedule For Big Boy 4014

Feb 25, 26 09:24 AM

Union Pacific Railroad has released the complete western leg schedule for its groundbreaking 2026 Big Boy No. 4014 Coast-to-Coast Tour.