Railroad Freight Cars (Trains): Types, History, Dimensions

Last revised: February 22, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The freight car has a long and fascinating history, tracing its heritage to England's primitive railroads of the 1820's. The earliest devices were made of wood, traveled on tramways pulled by horses/mules, and carried coal or quarried stone.

The Granite Railway of Massachusetts is recognized as the country's first, launched in 1826 to move granite from a quarry at Quincy to a dock on the Neponset River at Milton.

In his book, "Railroads Across America," historian Mike Del Vecchio notes the first use of iron rails occurred in 1740 at Whitehaven, Cumberland while the flanged wheel was introduced in 1789 at Loughborough, Leicestershire. The railroad gained acclaim in the United States soon after the Granite Railway entered service.

Pioneering systems like the Baltimore & Ohio, Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, South Carolina Canal & Rail Road Company, and Camden & Amboy worked to establish precedents which later became industry-wide standards.

The first freight cars were simple flatcars. As shippers requested specialization to handle specific products new types were born such as the boxcar, gondola, hopper, and tank car. In this section we will look at each, including a brief history which led to their development.

Photos

Conrail's "TripleCrown" roadrailer service is seen here passing through Gallitzin, Pennsylvania along the former PRR in July, 1994. American-Rails.com collection.

Conrail's "TripleCrown" roadrailer service is seen here passing through Gallitzin, Pennsylvania along the former PRR in July, 1994. American-Rails.com collection.Overview

After the Stockton & Darlington opened in England during September of 1825 railroad technology quickly made its way across the Atlantic. During those early years America leaned heavily on English influence.

When the B&O opened its original 13-mile main line from Baltimore to Ellicotts Mills (Ellicott City) it utilized simple passenger cars based from the stagecoach while freight was handled in rudimentary flatcars featuring a single axle at each end. Another B&O invention was the gondola, a classic car still in use today.

It was created in 1832 when the railroad took a basic flatcar and attached short side-boards to keep barrels of flour from falling out. Before long the limitations of both designs were recognized.

First, the ladding (freight) was exposed to weather while two rigid axles offered virtually no suspension.

While liquid or free-flowing products (like flour) could be hauled in sealed barrels carried in exposed cars the efficiency of doing so in a completely covered car held a great many advantages. This led to the development of first covered gondola by the Mohawk & Hudson in 1833.

A former Missouri Pacific gondola is seen here at Austin, Texas in early December of 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A former Missouri Pacific gondola is seen here at Austin, Texas in early December of 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.According to Mike Schafer's book, "Freight Train Cars," the use of springs was one of the earliest known freight car improvements.

By the 1830's the first four-wheel truck, one attached at each end, was employed on the B&O. The original inventor of the device has been lost to history although its advantages were unquestioned.

It was an iron (later steel) assembly capable of holding two axles with springs for suspension in-between. From a center bolster the truck swiveled freely beneath the car's frame.

The advantages were many including increased structural support, track wear reduction (by spreading out the car's weight more evenly), and an ability to more easily negotiating curves.

The truck was one of the few technological improvements railroads collectively embraced from an early period (others, such as the automatic air brake, knuckle coupler, and a universally standard-gauge took many years to gain acceptance).

As Mr. Schafer argues, American railroads began distancing themselves from English designs following development of this device.

Locomotives and cars grew ever larger as they were unencumbered by width restrictions associated with England's high-level station platforms (which allowed passengers to step directly onto trains instead of at ground level in the United States).

Norfolk & Western side dump car #514270 is seen here hauling what appears to be a load of riprap for right-of-way stabilization in March, 1983. These cars are often employed in such applications for maintenance-of-way (MOW). American-Rails.com collection.

Norfolk & Western side dump car #514270 is seen here hauling what appears to be a load of riprap for right-of-way stabilization in March, 1983. These cars are often employed in such applications for maintenance-of-way (MOW). American-Rails.com collection.The transport of aggregates and coal via a type of hopper, the "jimmy," was another invention born out of the early mining tramways. The first use of this car was employed on the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (also known as the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway) in 1827.

Interestingly, despite its creation, some railroads, like the B&O, were still using a flatcar-type contraption with large bins to haul coal into the latter 19th century. Without question the boxcar was the greatest developed during that period, evolving from the covered gondola.

A Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific 50-foot bulkhead flatcar (51', 6" inside length) is seen here in service during September of 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

A Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific 50-foot bulkhead flatcar (51', 6" inside length) is seen here in service during September of 1982. American-Rails.com collection.It was beloved for an ability to handle virtually everything from lumber to automobiles and could be found comprising entire trains through the mid-20th century.

In his book, "Field Guide To Trains: Locomotives And Rolling Stock," author and historian Brian Solomon points out that there 251,000 standard and 179,000 insulated/specially equipped boxcars in service through 1980.

However, following deregulation their combined total in 2010 had fallen to just 95,514. The reasons were many but largely due to mergers, loss of general manufacturing, and the rise in intermodal traffic.

Lettering And Markings

Below is a list of tables describing codes used by freight clerks to identify specific car types and/or what they handled in service.

These could be found on all types of paperwork such as waybills and lading forms to help keep an otherwise chaotic army of cars organized and efficiently on the move to the right destination.

Boxcars

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| XM | General Service: Equipped with side or side and end doors. |

| XI | General Service: Equipped with side or side and end doors. Insulated. |

| XAR | General Service: Equipped with side or side and end doors. Automobile loading racks. |

| XAP | General Service: Equipped with side or side and end doors. Auto-part loading racks. |

| XME | General Service: Equipped to handle/secure merchandise. Wood-lined. |

| XML | General Service: Equipped with stanchions and crossbars to secure freight. |

| XMP | General Service: Equipped for specific freight. |

Flatcars

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| FM | General Service. |

| FD | Depressed-Center Flatcar. |

| FC | Piggyback. |

| FA | Autorack. |

| LP | Bulkhead Flatcar. |

Gondolas

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| GB | Mill Gondola: Fixed/drop ends. |

| GS | Fixed sides/ends with drop bottom. |

Hoppers

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| HM | Twin Bays. |

| HT | Triple Or Quadruple Bays. |

| HD | Twin-Bay Ballast Car. |

| LO | Covered Hopper. |

Reefers/Refrigerator Cars

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| RB | Bunkerless (no ice). Only insulated. |

| RBL | Bunkerless (no ice). Only insulated. Changeable interior loading fixtures. |

| RS | Bunkers (ice). |

| RSB | Bunkers (ice). Circulation fans. Mechanical loading devices. |

| RSM | Bunkers (ice). Beef rails. |

Special Service

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| LF | Container/Well Car. |

Tank Cars

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| TA | Standard Tank Car. |

| TG | Standard Tank Car. Glass Lined. |

If it were up to railroads, boxcars would probably still be in widespread use today. The redundancy they offered was unmatched. Shippers, though, continued pushing for unique types to meet ever-greater needs.

One of the first truly specialized designs was the tank car, born following Edwin Laurentine Drake (Colonel Drake) discovering of oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania during August of 1858.

This vital fossil fuel was viscous and could not be transported in a standard gondola or boxcar. The first of its kind was essentially a basic flatcar featuring horizontal vats.

But this system proved too cumbersome and inefficient so within a few years the more modern horizontal tank with a centralized top dome and safety valve came into use. In the 1890's the first steel tank cars appeared.

Interestingly, through the early 20th century they could still be found manufactured of wood, with a tank that looked like a barrel on its side, suspended above a support system which was then attached to a steel underframe.

Over time the car became larger and heavier, carrying many other products ranging from basic water to dangerous chlorine.

A Detroit, Toledo & Ironton 85-foot flatcar, #90142, is seen here in service during September of 1982. These cars typically handled truck trailers. American-Rails.com collection.

A Detroit, Toledo & Ironton 85-foot flatcar, #90142, is seen here in service during September of 1982. These cars typically handled truck trailers. American-Rails.com collection.The transition from wood to iron/steel in car construction first appeared during the 1880s. At this time it was used predominantly in the areas of structural integrity such as sills and trusses.

Eventually, steel became the preferred means for all components due to its superior strength. However, just as with the tank car, equipment carrying some elements of wood remained in use as late as the 1960's.

These were predominantly outside-braced boxcars and gondolas, which would pop up from time to time at local sidings.

After the Federal Railroad Administration set a 50-year shelf life on all rail equipment (mandating a ten-year period between overhauls) the wooden cars were finally forced into retirement.

The basic freight car designs fell into one of seven categories; autoracks, gondolas, hoppers, tank cars, well/spine cars, boxcars, and the common flatcar. Of these, the well/spine car and autorack are relatively new, developed after World War II to handle automobiles and intermodal freight.

Car Types

An aging wooden Great Northern caboose still looks good as it rides along on a Burlington Northern freight, which is operating over the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range at Iron Junction, Minnesota during August of 1976. Rob Kitchen photo.

An aging wooden Great Northern caboose still looks good as it rides along on a Burlington Northern freight, which is operating over the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range at Iron Junction, Minnesota during August of 1976. Rob Kitchen photo.Modern Designs

Today, specialization remains a vital part of the railroad industry. Take, for instance, the flatcar which has morphed far beyond a basic horizontal bed with trucks.

In contemporary times there is the aforementioned spine car (a special flatcar to haul truck trailers), bulkhead flat (carrying very high ends to haul products like pulpwood), depressed-center flat (to haul incredibly heavy loads), and spine-bulkhead flat (this special unit carries a center sill for added strength to haul special loads like insulation).

The gondola is another example; they can now be found hauling coiled steel in what are called coil cars or feature higher sides with a drop bottom to transport coal.

Finally, there is specialization of the utilitarian boxcar; two of its more important refinements included open-slats to haul livestock, such as cattle and pigs, and refrigeration.

The so-called reefer got its start in the 1850's. For many years ice did the trick via heavy insulation to keep the product cool.

Later, mechanization did away with the standard icing stations needed at various points to repack ice. Today, reefers are still found in widespread use but the stock car has been relegated to history.

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:57 PM

The Wisconsin Great Northern Railroad will once again welcome passengers aboard its popular Spring BBQ Dinner Train in 2026. -

Connecticut DOT Awards $20 Million In Railroad Grants

Mar 12, 26 01:19 PM

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) has announced a new round of funding aimed at improving the safety, reliability, and capacity of the state’s freight rail network. -

California's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 12:59 PM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Reading & Northern Unveils Semiquincentennial 1776

Mar 12, 26 12:48 PM

In November 2025, the Reading, Blue Mountain & Northern Railroad (RBMN)—commonly known as the Reading & Northern—announced the debut of a striking patriotic locomotive commemorating the upcoming 250th… -

New Jersey's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:35 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Florida BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:28 AM

While Florida does not currently offer any BBQ train rides the Florida Railroad Museum does host a similar event, a campfire experience! -

Texas "Murder Mystery" Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:40 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:36 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

Missouri's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:33 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:28 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Charlotte Approves $37.9M For "Red Line" To Lake Norman

Mar 11, 26 02:18 PM

The Charlotte City Council has approved $37.9 million in funding for the next phase of design work on the long-planned Red Line commuter rail project. -

NS, Progress Rail Announce SD70ICC Modernization

Mar 11, 26 12:15 PM

Norfolk Southern Railway has announced a significant locomotive modernization initiative in partnership with Progress Rail Services Corporation that will rebuild 96 existing road locomotives into a ne… -

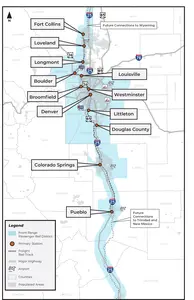

Colorado Seeks Input On Proposed Front Range Passenger Train Name

Mar 11, 26 11:55 AM

Colorado officials are inviting the public to help name a proposed passenger train that could one day connect major cities along the state’s heavily traveled Interstate 25 corridor. -

Virginia Whiskey Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 11:22 AM

Among the Virginia Scenic Railway's most popular specialty excursions is the “Bourbon & BBQ” tasting train, an adults-oriented rail journey that pairs scenic views of the Shenandoah Valley with guided… -

Minnesota's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:32 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train. -

New Mexico's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:23 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Indiana's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:19 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:02 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Kentucky Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 11:39 AM

The Bluegrass State is home to beautiful rolling farms and the western Appalachian Mountain chain, which comes alive each spring. A few railroad museums host Easter-themed events during this time. -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:26 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

NS Faces Multiple Derailments Near Historic Horseshoe Curve

Mar 10, 26 10:15 AM

One of America’s most famous railroad landmarks, the legendary Horseshoe Curve west of Altoona, Pennsylvania, has recently been the site of multiple freight-train derailments involving Norfolk Souther… -

Oregon's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:11 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:57 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Connecticut's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:54 AM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on… -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:37 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Union Pacific Restores Rail Bridge Service in Lincoln

Mar 09, 26 11:34 PM

Union Pacific crews have successfully restored freight rail service across a key bridge in Lincoln, Nebraska, completing a rapid reconstruction effort in just a few weeks. -

TVRM To Assist In Gas-Powered Locomotive's Restoration

Mar 09, 26 11:15 PM

The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum has announced it is assisting in the eventual cosmetic restoration of a former gas powered locomotive used in the logging industry. -

Michigan's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:37 AM

Spring sometimes comes late to Michigan but this doesn't stop a handful of the state's heritage railroads from hosting Easter-themed rides. -

Pennsylvania's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:05 AM

Pennsylvania is home to many tourist trains and several host Easter-themed train rides. Learn more about these special events here. -

Tennessee's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:33 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Michigan's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:07 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:56 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Maryland Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:37 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

New York's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:16 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:15 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Colorado Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:14 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:13 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 1356 Receives Cosmetic Restoration

Mar 07, 26 02:19 PM

A significant preservation effort is underway in Missoula, Montana, where volunteers and local preservationists have begun a cosmetic restoration of Northern Pacific Railway steam locomotive No. 1356. -

New York's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 02:08 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Kentucky's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:17 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Ohio's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:15 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

Georgia 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides In Cordele

Mar 07, 26 10:13 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel… -

Arizona Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:12 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Massachusetts's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 09:00 AM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:57 AM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

Indiana's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:55 AM

Among IRE’s most talked-about offerings is the Wine & Whiskey Train—an adults-only, evening-style trip that leans into the best parts of classic rail travel: atmosphere, comfort, and a little cele… -

North Carolina's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:53 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Arkansas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:50 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

California Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:49 AM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Construction Continues On Railroad Museum Of Pennsylvania Roundhouse

Mar 05, 26 01:52 PM

Construction is underway on a long-anticipated roundhouse exhibit building at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, a project designed to preserve several of the most historically signific…