Class 1 Railroads (USA): Revenue, Statistics, Overview

Last revised: February 27, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The history of the Class 1 railroad traces back to our country's first common-carrier, the Baltimore & Ohio. During the next century more than 140 such systems came to serve this great country.

After World War II a series of mergers, bankruptcies, and takeovers reduced the number to the current seven.

These enormous operations are spread throughout North America and include Canadian National, Canadian Pacific Kansas City, CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern, Union Pacific, and BNSF Railway.

There was a major shakeup in the North American rail map following CP's announcement on March 21, 2021 that it would acquire KCS. The new railroad became known as Canadian Pacific-Kansas City.

Interestingly, rival Canadian National had soon made a counterproposal of $33.6 billion to acquire KCS. It appeared CN would be the winning bidder before Surface Transportation Board unanimously rejected the proposal on August 31, 2021, paving the way once more for the CP-KCS union.

As the industry leaders these six Class 1's contain the most trackage, largest annual operating revenue, greatest number of employees, and newest locomotives.

With annual earnings in the billions Class 1's are always at the forefront of technology and innovation. The long-held dream since the early 20th century has been the creation of a true, transcontinental railroad. To date this hope remains elusive.

However, the chances are high that one day two gigantic railroads linking the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans will eventually become a reality.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe C44-9W #4723, the official Microsoft Train Simulator locomotive, is seen here on display at St. Louis Union Station in May, 2001. American-Rails.com collection.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe C44-9W #4723, the official Microsoft Train Simulator locomotive, is seen here on display at St. Louis Union Station in May, 2001. American-Rails.com collection.Definition and Revenue

While the monetary figure designating a Class 1 has changed over time its principal meaning has remained the same; it is the largest railroad, in terms of annual operating revenue, based in either the United State or Canada.

During the industry's classic era, predating the 1970's, such a carrier could have been only a few hundred miles in length as long as it met the minimum operating revenue.

Small names then like the Detroit & Mackinac, Lehigh & Hudson River, Green Bay & Western, and Spokane International all earned sufficient revenue to wear the designation of Class 1.

Today, this has vastly changed as no railroad smaller than Canadian Pacific-Kansas City's 20,000 route miles holds such a title.

As of 2021, the Association of American Railroads (AAR) defines a Class 1 as having operating revenues of, or exceeding, $900 million annually (previously the figure had been $505 million).

At A Glance

The association also notes, "...[Class 1's] contain 69% of the industry’s mileage, 90% of its employees, and 94% of its freight revenue.

They operate in 44 states and the District of Columbia and concentrate largely on long-haul, high-density intercity traffic."

(The latter point is a stark change from years ago when railroads sought local and less-than-carload, or LCL, business.)

History

In 1939 a premier U.S. railroad was defined as having annual operating revenues of at least $1 million. However, this figure has been updated several times over the years to meet inflation and other market factors.

For instance, in 1956 it was revised to $3 million, $5 million in 1965, $10 million in 1976, $50 million in 1978, $250 million in 1993, $319.3 million in 2005, $475.5 million in 2014, and $505 million in 2019.

As railroads felt the pinch of federal regulation and competition they turned to merger as a way of reducing costs.

It's the early Burlington Northern Santa Fe era as a pair of former Santa Fe GP60M's, led by #129, along with BNSF C44-9W (#1014), work an eastbound up the west side of Cajon Pass at Blue Cut, California in June, 1997. American-Rails.com collection.

It's the early Burlington Northern Santa Fe era as a pair of former Santa Fe GP60M's, led by #129, along with BNSF C44-9W (#1014), work an eastbound up the west side of Cajon Pass at Blue Cut, California in June, 1997. American-Rails.com collection.These consolidations eventually resulted in today's seven conglomerates. In addition, mileage was abandoned when deemed superfluous, shrinking from 1916's peak figure of 254,037 to 138,000 today. Of the current mileage Class 1's own about 95,000, or 68%.

Much of the rest (32%) has been spun off to short lines or regionals, many formed in the post-Staggers Act era (1980). In all, there are more 560 railroads currently in operation across the country including Class 1's, regionals (Class 2's), and short lines (Class 3's).

Could There Ever Be A New Class 1?

In today's modern age it is unlikely a new Class 1 will ever appear although the idea is not entirely impossible. For instance, during the 1990's a growing Wisconsin Central came close to achieving this threshold.

It was formed in January of 1987 when Soo Line sold 2,300 miles of track stretching from northern Illinois, into the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and across Wisconsin.

By the 1990's it had transformed this derelict trackage into a profitable enterprise eclipsing $100 million annually. Perhaps weary of its growing influence, Canadian National purchased the carrier in 2001.

If a similar situation were to occur today, another prominent regional would be the obvious candidate. The most likely way for this to occur, of course, would be some type of continued growth through new acquisition.

During the industry's formative era it was relatively easy to acquire property for new route construction. The difficulty lay in gaining the necessary funding for actual grading and materials.

Unfortunately, the thought of doing this today is nearly unheard of due to the extensive regulatory process, environmental laws, and public opposition ("NIMBY," Not-In-My-Backyard). A good example is the Tongue River Railroad of southern Montana.

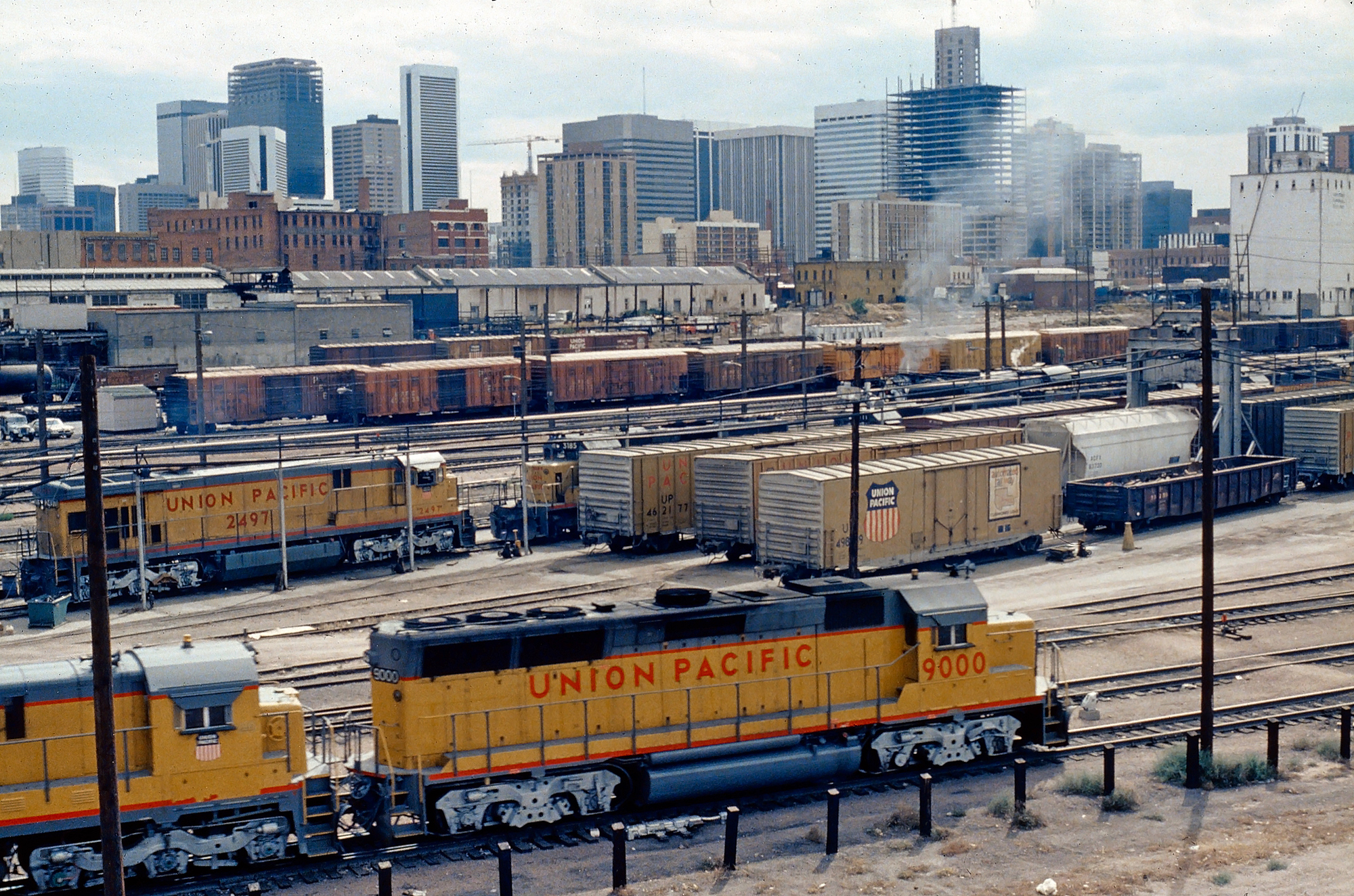

Union Pacific power, including GP40X #9000, along with C30-7 #2497 and SD40-2 #3185, layover at Rio Grande's Burnham Shops in downtown Denver, Colorado, in the summer of 1982. Barely visible in the background is Union Pacific 4-8-4 #8444, which was hosting excursions from Denver to Sterling. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific power, including GP40X #9000, along with C30-7 #2497 and SD40-2 #3185, layover at Rio Grande's Burnham Shops in downtown Denver, Colorado, in the summer of 1982. Barely visible in the background is Union Pacific 4-8-4 #8444, which was hosting excursions from Denver to Sterling. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.The first proposal for this new 80-mile route was launched in 1981; projected to serve a surface coal mine at Ashland it would reach Miles City and link with the then-Burlington Northern (now BNSF Railway).

After numerous battles with environmental groups and land owners, all the while completing several environmental studies, the Surface Transportation Board (STB) finally rejected the idea in April of 2016.

The other possibility would be to revive a long-abandoned corridor. This idea has been carried out in a few cases since the 1990's but only along short stretches.

The thought of seeing a major rebuild, such as the Milwaukee Road's Pacific Coast Extension (central Montana to Seattle), the Erie Railroad's/Erie Lackawanna's Chicago main line (Ohio to Chicago), or Baltimore & Ohio's St. Louis main line (central West Virginia - southern Ohio) appears unlikely for the same reasons previously mentioned.

While these lines were direct, high-quality corridors that saw extensive use, even up until their abandonment (the closing of all three remains a hot-button issue), the idea of reactivation is remote.

But, there are many miles of preserved rights-of-way all across the country, railbanked for the express purpose of possible future use.

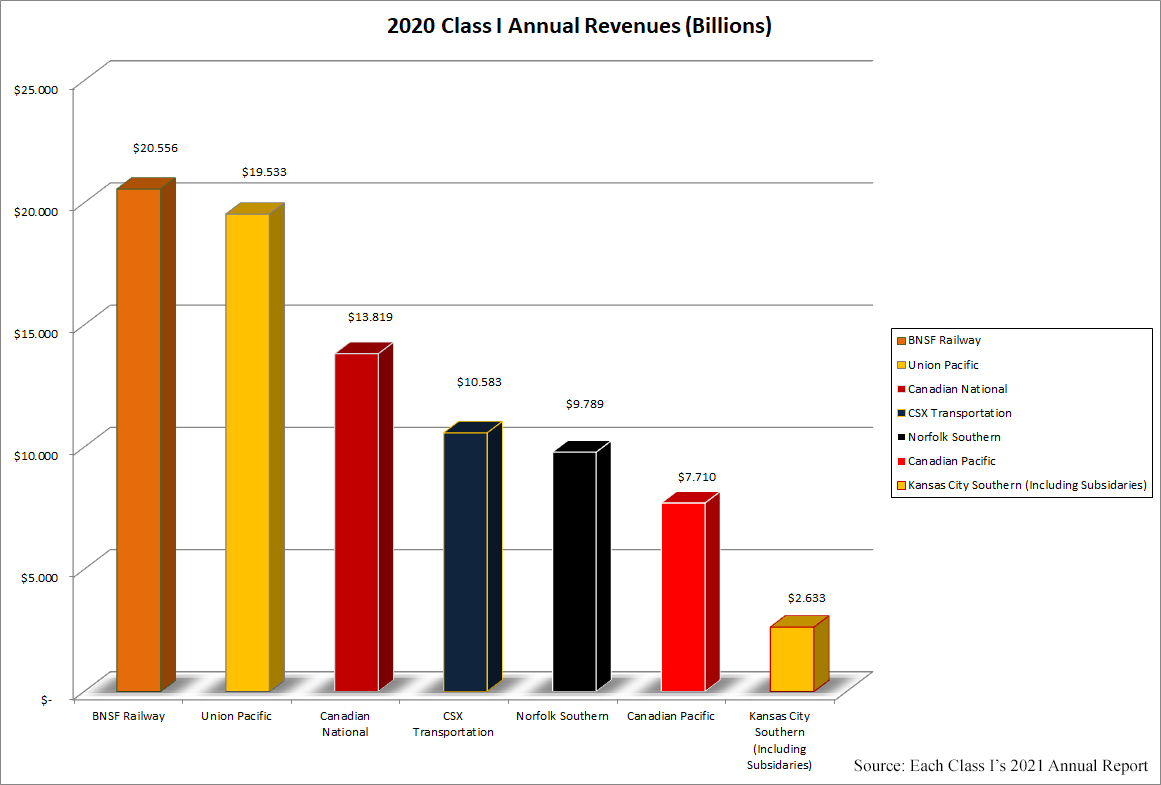

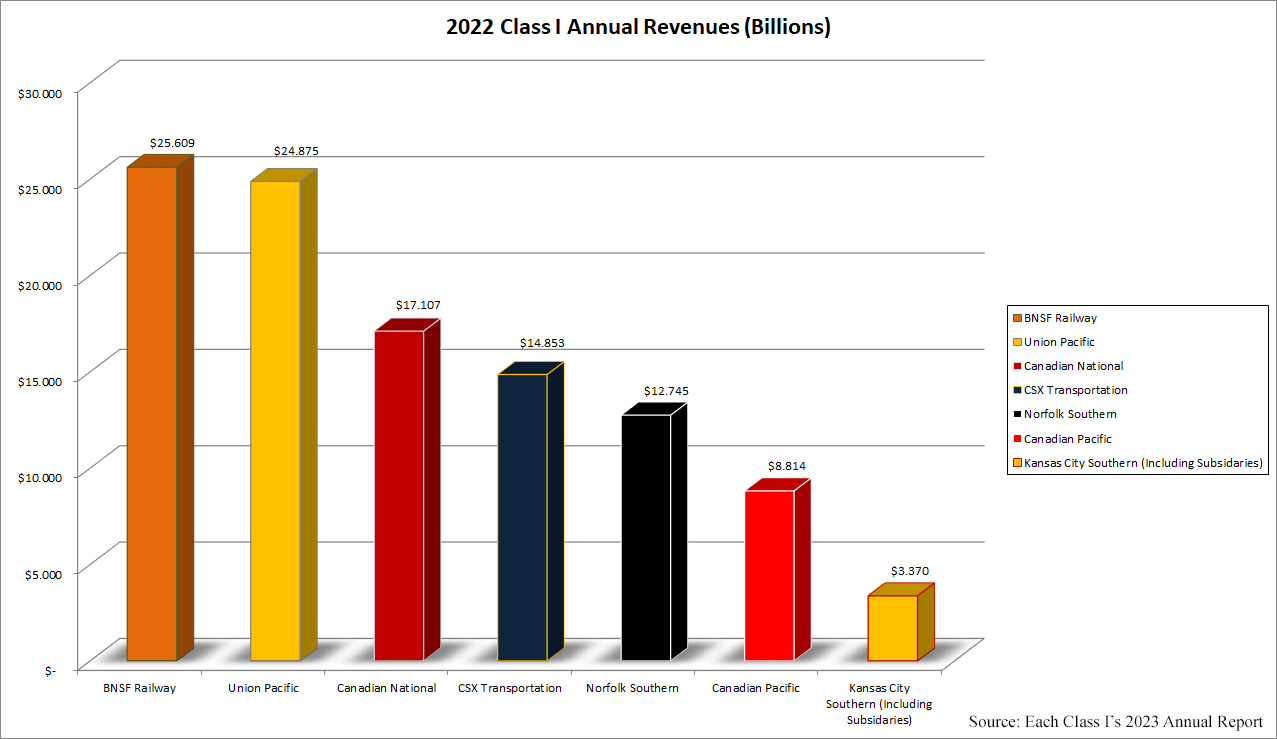

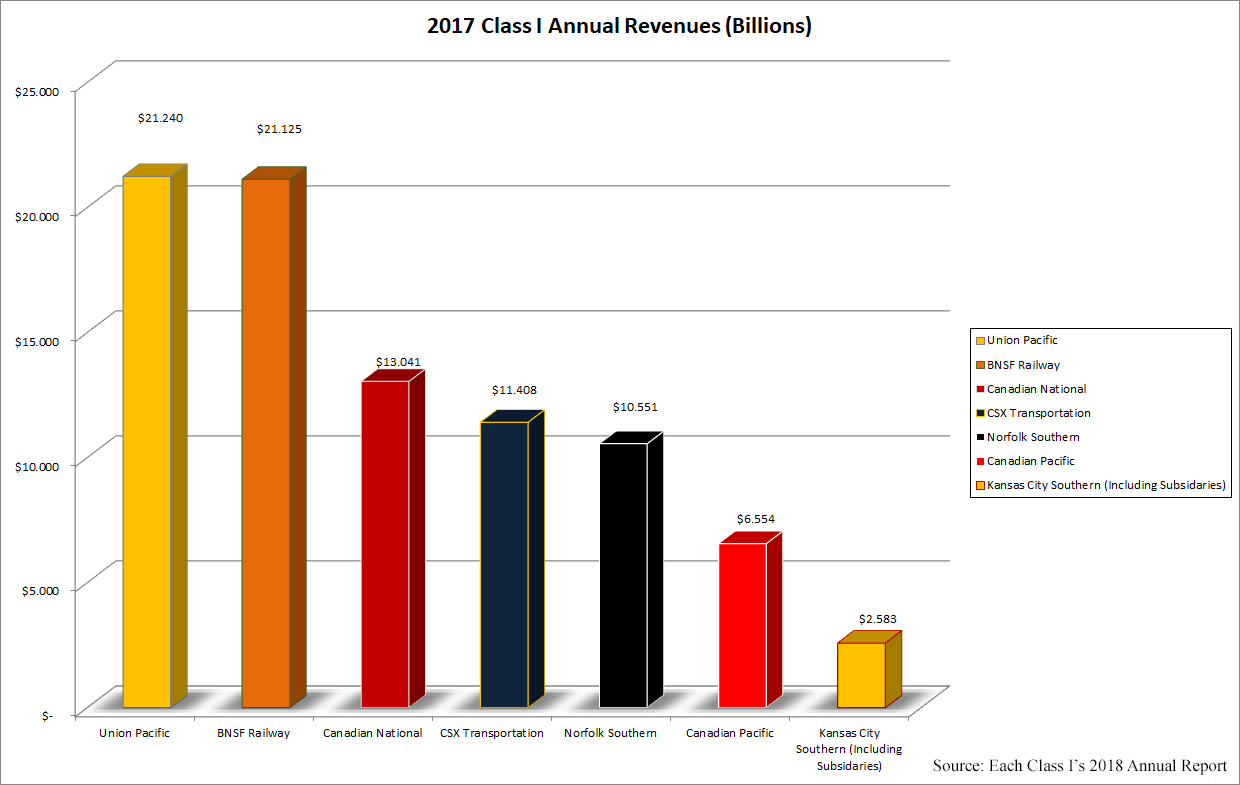

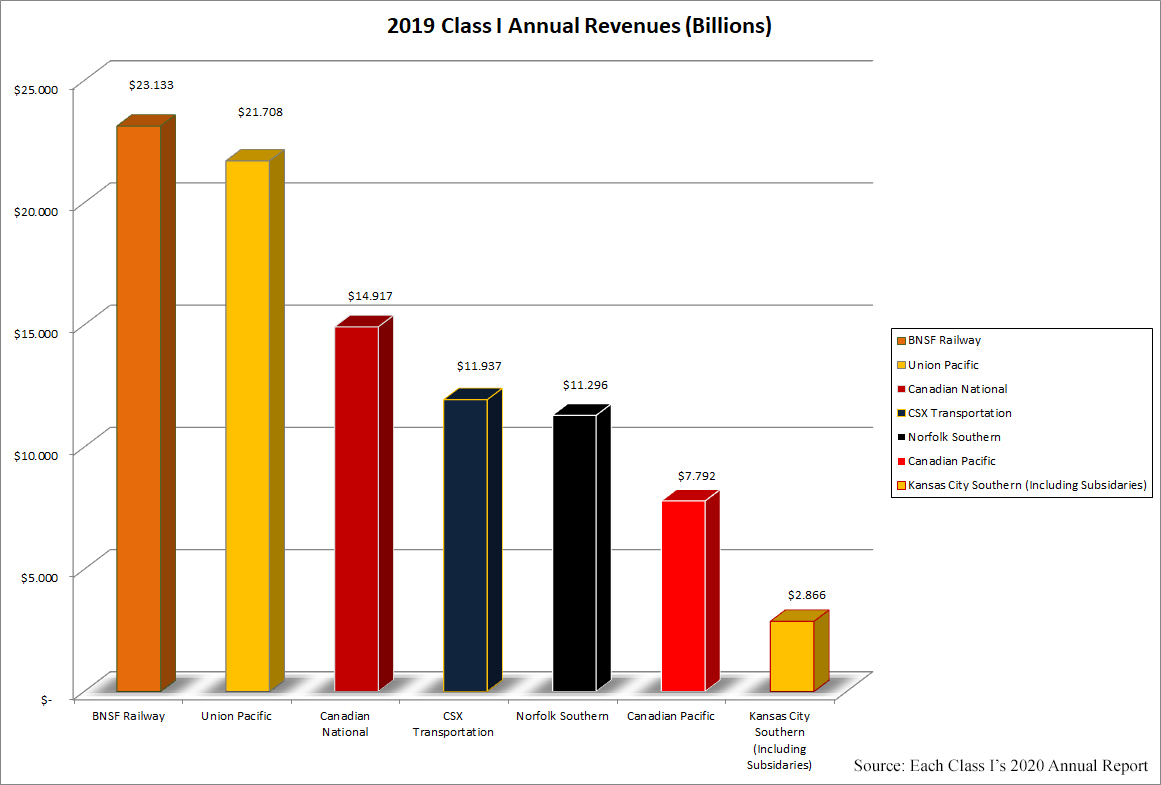

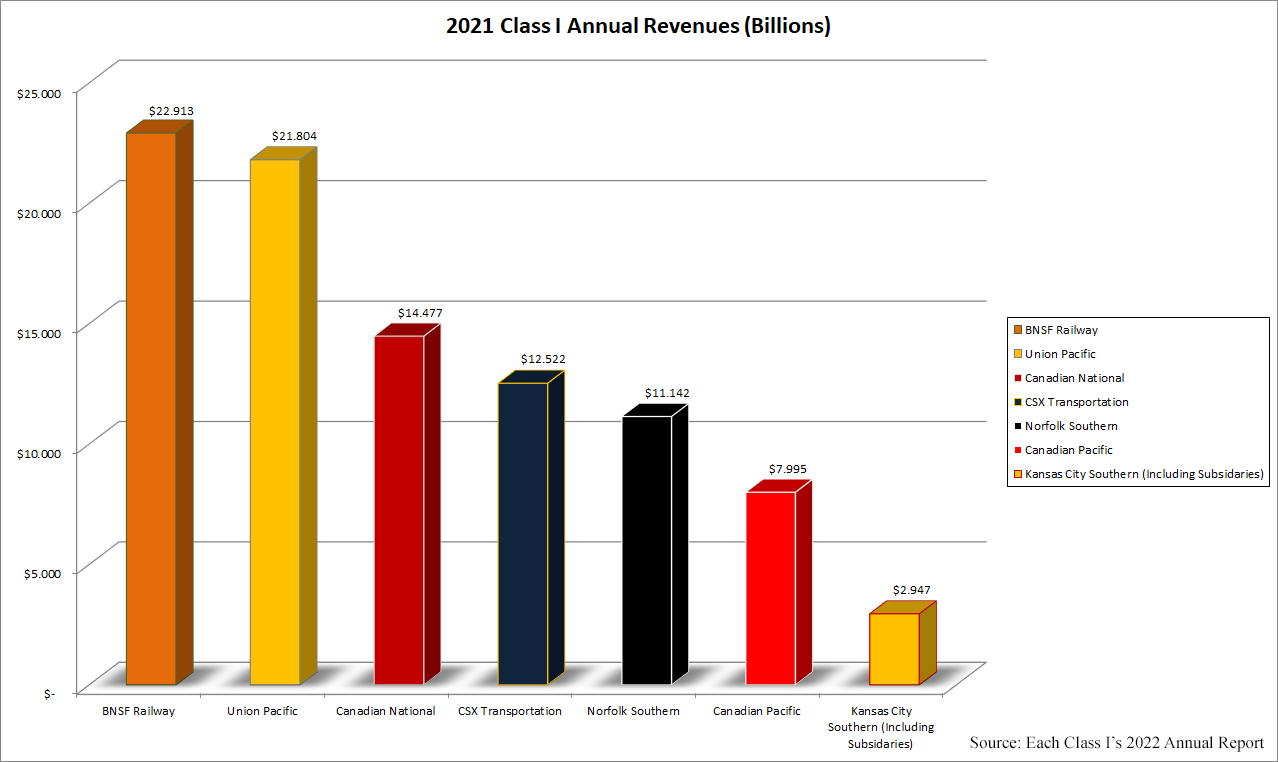

The below tables highlight each railroad (including Canadian National) regarding their 2020 operating revenue (the latest figures available). Leading the pack is Union Pacific and BNSF Railway; the former an American institution.

For generations UP has carried strong profits and keen management, traits which enabled the Omaha-based road to fluidly navigate the turbulent 1970's. BNSF Railway was a 1995 merger of Burlington Northern and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, two of the West's largest systems.

The Santa Fe was especially noteworthy, known worldwide for its legendary Chiefs and the only pre-merger railroad to boast its own transcontinental main line from Chicago to Los Angeles.

The BN came into existence on March 2, 1970 through the Burlington, Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Spokane, Portland & Seattle. BNSF is the only Class 1 privately owned, purchased by Warren Buffett in late 2009. Also of note is the Kansas City Southern.

Its heritage can be traced back to 1887 where it eventually grew into a modest network linking Kansas City with the Gulf Coast. Beginning in the 1990's a series of takeovers pushed its network from Mexico to Chicago (via trackage rights).

Statistics

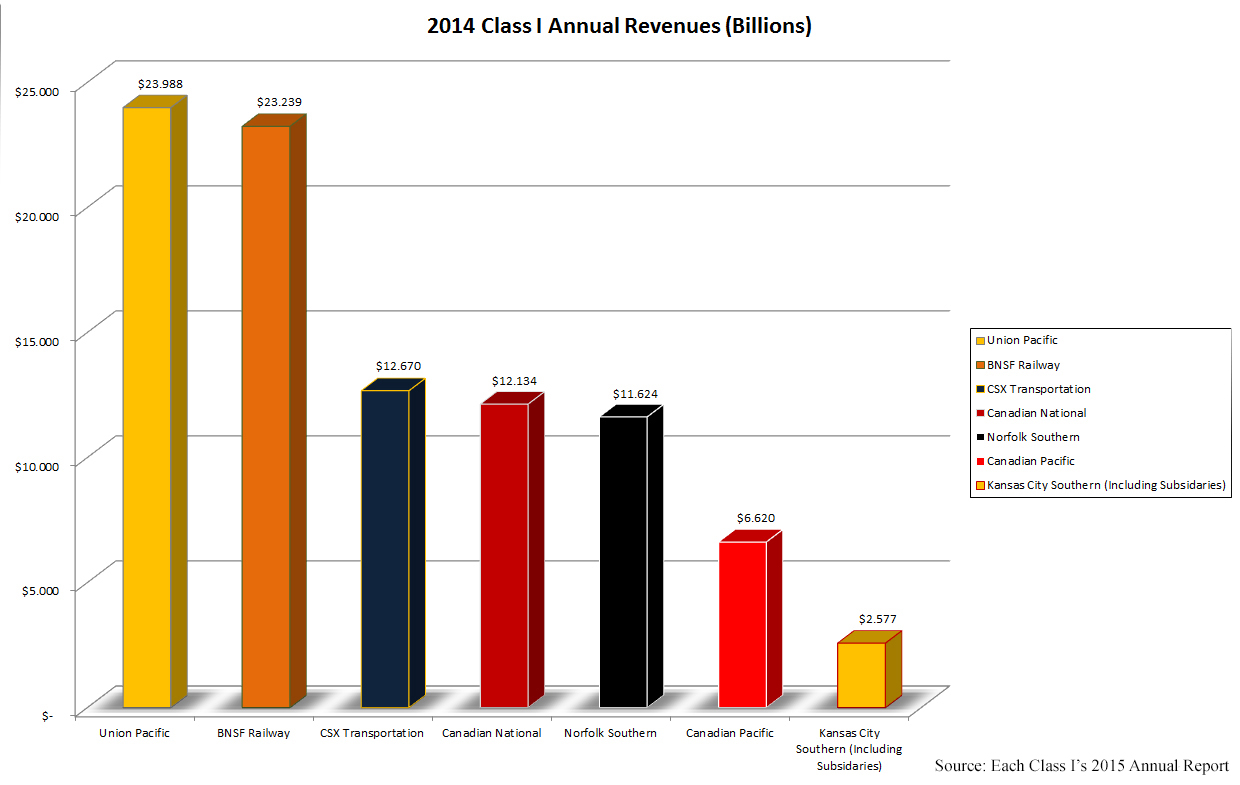

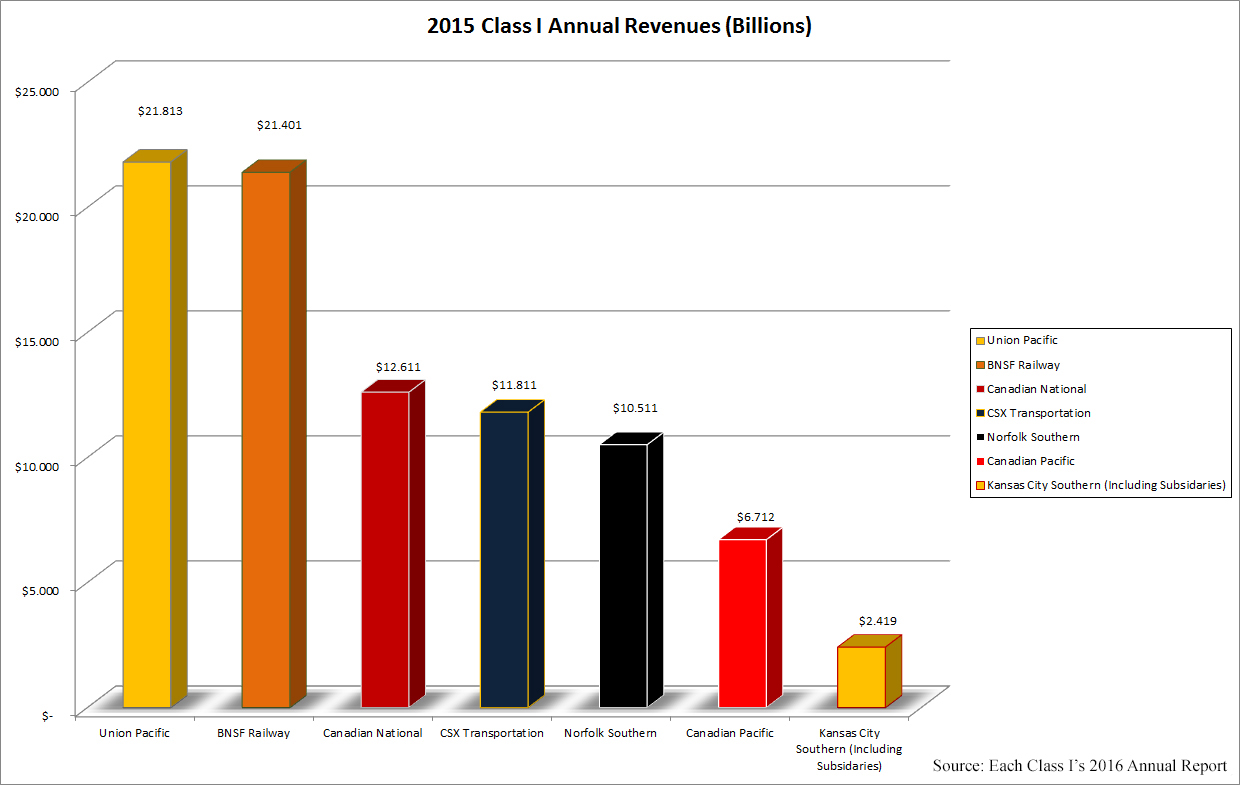

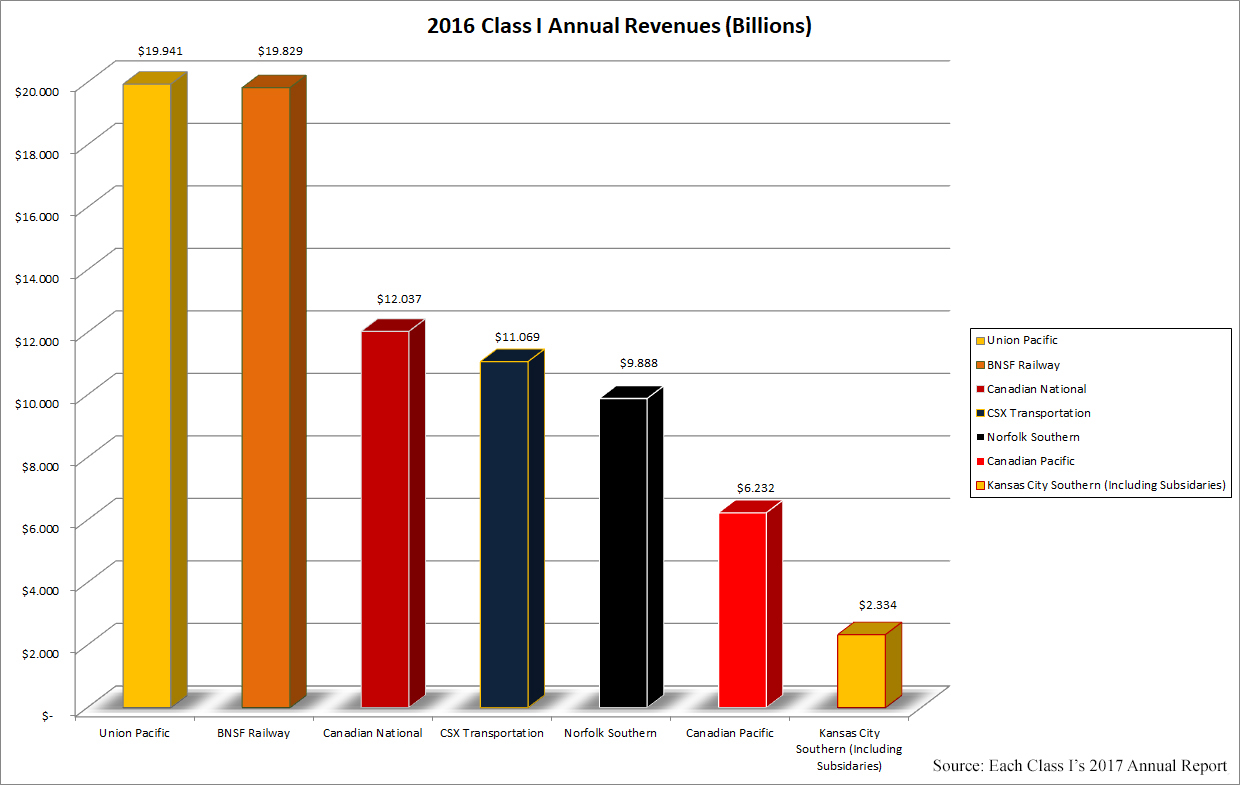

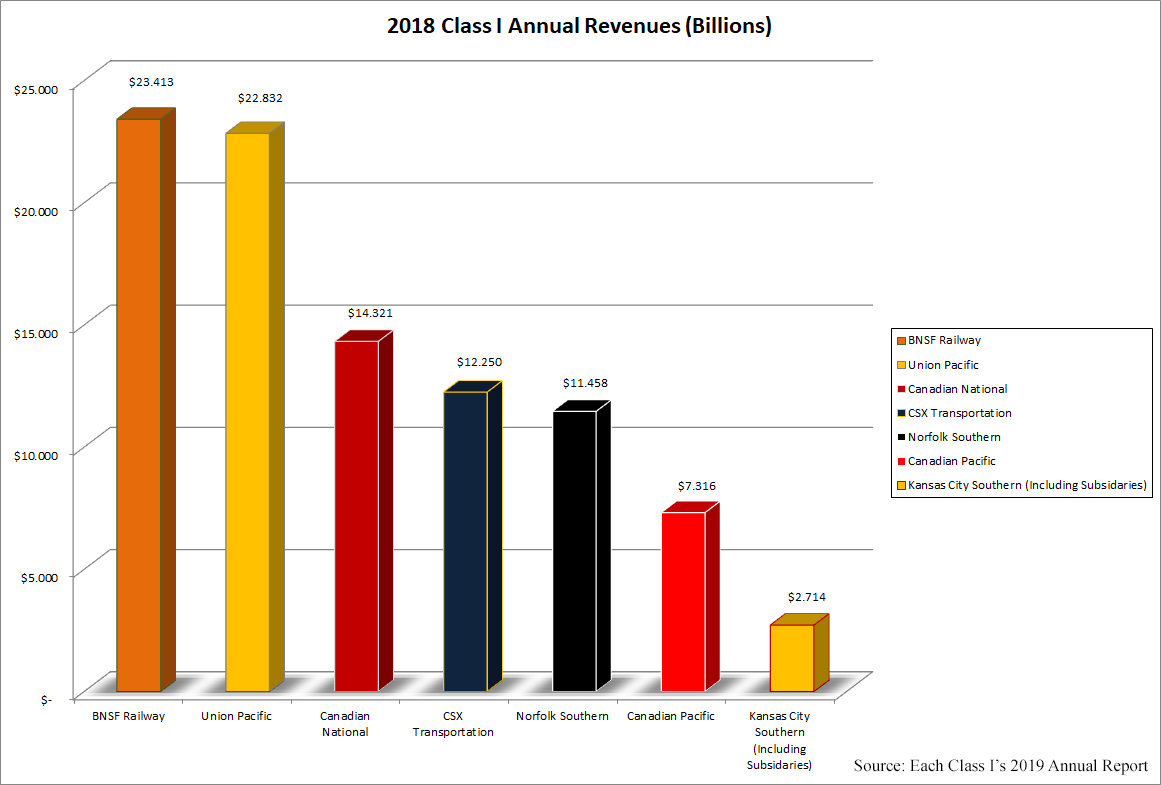

Note that in the below graphs, Canadian National has overtaken CSX as the third highest-grossing Class 1. This can be partially blamed on shifting traffic patterns and the loss of coal tonnage while CSX's leadership has also come into question.

For more statistical data please click here. As you can see from the previous link, the Association of American Railroads' website provides a great wealth of the information for research purposes.

If you are interested in digging deeper into railroad statistics, another fine resource is the Bureau of Transportation Statistics' website.

Annual Reports

Revenues (Since 2014)

One of the industry's most interesting recent developments occurred in the fall of 2015 when Canadian Pacific openly announced plans to seek a merger with Norfolk Southern. CP had already sought a similar union with CSX, which flatly rejected the idea.

The Canadian road, through then-CEO, E. Hunter Harrison, sent a letter to NS in November, 2015 hoping for a friendly response.

But after some time, and careful deliberation, NS also turned down the proposal. CP continued to pursue the endeavor by sending additional requests, each also rejected.

Despite talk of a potential hostile takeover CP quietly dropped the idea. Had the marriage taken place it would almost certainly have caused a domino effect of other mergers, resulting in two gigantic, coast-to-coast railroads.

Current Railroads

Burlington Northern Santa Fe SD70MAC #8957, wearing the "Heritage II" livery, and SD70MAC #9787, sporting the "Executive" scheme, have a cut of loaded coal hoppers at Oregon, Ohio on the Norfolk Southern in March, 2002. American-Rails.com collection.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe SD70MAC #8957, wearing the "Heritage II" livery, and SD70MAC #9787, sporting the "Executive" scheme, have a cut of loaded coal hoppers at Oregon, Ohio on the Norfolk Southern in March, 2002. American-Rails.com collection.In the end, it was not a particularly savvy proposal fraught with numerous issues, the least of which was U.S/Canadian regulatory complications.

Many experts considered the marriage a bad business decision for this reason and others. During the entire process CP had drawn little support, from within the industry and among shippers.

Interestingly, as mentioned at the top of this article, CP has continued to look for a merger partner and appears it will acquire Kansas City Southern to form the Canadian Pacific-Kansas City Railroad. The merger is expected to be finalized within the next 18-24 months

Recent Articles

-

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra…