Amtrak: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation

Last revised: February 24, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Our country's intercity rail carrier, Amtrak (officially the the National Railroad Passenger Corporation), is a unique, interesting, and little understood entity which has served the public since 1971.

Its creation came about solely to sustain a service which private railroads could no long afford. After many years of planning and lobbying, President Richard Nixon signed into law the bill that would later establish Amtrak.

Unfortunately, the carrier was designed to neither succeed nor survive; after its subsidy expired many believed it would simply shutdown.

As Tom Carper writes in the book, "Amtrak: An American Story," the president of Burlington Northern stated, "I guarantee you, Amtrak will not last more than five years." This assertion would very likely have came true if not for the rallying cry of so many.

Amtrak SDP40F #601 is stopped with its train at the Route 128 Depot in Massachusetts on October 16, 1974. Robert Newbegin photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Amtrak SDP40F #601 is stopped with its train at the Route 128 Depot in Massachusetts on October 16, 1974. Robert Newbegin photo. American-Rails.com collection.History

Such strong public support spared Amtrak from a certain fate although has not guaranteed its future. During its last 40+ years the company has lived a meager existence, surviving on woefully inadequate funding despite nearly doubling its ridership since 1971.

Amtrak will likely carry on as it always has, providing a vital service for millions of Americans without the benefit of sufficient capital. The following article is a brief overview of its history and present-day operations.

Today, rail travel is stronger than ever, particularly between intermediate points, as Americans look to escape evermore highway congestion. Since the year 2000, when the high-speed Acela Express was introduced on the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak has witnessed a 41% leap in ridership.

Photos

Amtrak E8A #437 leads train #31, the westbound "National Limited," through Coshocton, Ohio on June 26, 1977. American-Rails.com collection.

Amtrak E8A #437 leads train #31, the westbound "National Limited," through Coshocton, Ohio on June 26, 1977. American-Rails.com collection.It now handles more than 30 million travelers annually. In addition, several states subsidize some type of commuter/intrastate service, or contract with Amtrak to do so. Perhaps the two most noteworthy are North Carolina and California.

Both are doing incredible work by developing corridors in their respective states as an alternative to pavement; North Carolina continues its endeavor for an intrastate route Wilmington to Asheville while California has numerous services linking its largest cities.

Other states supporting commuter rail include Washington, Florida, Virginia, Texas, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and New Mexico while others have commuter rail projects in development.

The story of Amtrak begins decades prior to its creation. Many moons ago, America enjoyed worldwide envy by offering top-notch passenger service.

These trains of yore remain fondly remembered today. Rail travel in the United States can be traced back to the tiny Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, a gravity railroad that began in 1827.

The operation primarily handled anthracite coal from mines situated in Eastern Pennsylvania to the nearby Lehigh Canal.

However, it has also been documented the LC&N hosted passengers as early as the summer of 1829. The first railroad to operate a passenger train pulled by an American-built steam locomotive was the South Carolina Canal & Railroad Company, once the longest in the world connecting Charleston with Hamburg.

Its locomotive, the Best Friend of Charleston (a product of the West Point Foundry in New York) carried the first paying customers on December 25, 1830. From that point, railroads in America were a mainstay allowing the public to move between far away points in mere hours or days instead of weeks or months.

In this book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," author and historian John F. Stover provides an overview of how the iron horse so dramatically changed how folks traveled.

In 1800, an individual making a trip from New York City would need at least three weeks to reach the western frontier of what is now Ohio and Kentucky.

It was an arduous, uncomfortable, and sometimes dangerous affair that carried few luxuries. At that time there were only two notable roadways in service; the Philadelphia & Lancaster Turnpike Company (our nation's first toll road) which served eastern Pennsylvania and the National Road connecting Cumberland, Maryland and Wheeling, Virginia.

As the 19th century progressed, canals gained widespread fervor which was immediately followed by the railroad's development.

Our country's first common-carrier (established specifically for public use), the Baltimore & Ohio, was chartered on February 28, 1827 and officially incorporated and organized on April 24, 1827.

The B&O hosted its first passengers over its initial 1.5 miles from Baltimore, Maryland's Pratt Street during January of 1830. Later that May, 13 miles had been opened to Ellicotts Mills (today Ellicott City) where a sturdy, two-story stone depot and small turntable were built.

Aging Santa Fe F7's labor on under the Amtrak banner with a "San Diegan" at the beautiful station in San Diego, California during March of 1973. Drew Jacksich photo.

Aging Santa Fe F7's labor on under the Amtrak banner with a "San Diegan" at the beautiful station in San Diego, California during March of 1973. Drew Jacksich photo.Three decades following the B&O's groundbreaking, more than 30,000 miles of tracks crisscrossed the eastern U.S.

Thanks to this extraordinary and rapid infrastructure development, travel time from New York was vastly reduced; one could now reach Chicago in just two days or the territories of Nebraska and Kansas in only a week.

As technology advanced and the industry became better organized, speeds continued to increase.

For instance, as Mark Wegman points out in his book, "American Passenger Trains And Locomotives Illustrated," New York Central & Hudson River (New York Central) 4-4-0 #999, which led the crack "Empire State Express," became the world's first locomotive to surpass 100 mph when it reached 112.5 mph over a 1-mile stretch near Batavia, New York on May 10, 1893.

Its achievement immediately earned worldwide acclaim and thanks to the good PR, NYC&HR showcased the "American" type at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago that year. Just prior to U.S. involvement in World War I, railroads reached their zenith with the industry boasting a network of 254,037 miles in 1916.

Again, most of this was concentrated east of the Great Plains. It could also be rightfully argued that in some regions, particularly the Heartland, overzealous competition led to considerable over-development.

But with little competition there was great money to made in railroads during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The year 1916 also witnessed one of the highest percentages of people and goods moving by train, accounting for an incredible 98% of intercity travel and 77% of intercity freight.

Unfortunately, these numbers slowly declined after this recording-breaking year. On October 1, 1908 Ford Motor Company's first Model T rolled off the assembly line and the country's future changed forever.

By 1917 nearly 5 million automobiles were registered in the United States, a number that quickly rose as these innovative machines provided Americans unprecedented freedom.

Streetcars and interurbans, electrified commuter railroads situated between, or within, local population centers, felt the effects first. Since their inception, they had largely struggled to compete against their larger counterparts.

Logos

A few had been successful (like the Pacific Electric; Chicago, Aurora & Elgin; Illinois Terminal; and Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee) but, as John Due and George Hilton point out in their authoritative title, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," many were on the verge of bankruptcy by World War I.

Even during that era of poor roads and spindly automobiles, the novel motorized machines could easily erode the trolley's market share. Those which survived were either done in by the depression or called it quits by World War II (a few managed to continue on as standard freight carriers).

Amtrak P30CH "Pooch" #721 has "The Illini" at the east end of the St. Charles Air Line heading southtbound out of Union Station and is about to swing on to the Illinois Central in August, 1978. Rick Burn photo.

Amtrak P30CH "Pooch" #721 has "The Illini" at the east end of the St. Charles Air Line heading southtbound out of Union Station and is about to swing on to the Illinois Central in August, 1978. Rick Burn photo.For major steam railroads, the 1920's saw a dip in patronage but it was the Great Depression, and subsequent economic downturn, which greatly hurt ridership. To combat the losses Union Pacific introduced the flashy streamliner in 1934.

The so-called "M-10000" (or simply "The Streamliner" as UP described it) debuted in February that year and was followed just weeks later by Chicago, Burlington & Quincy's Pioneer Zephyr (also known as the "Zephyr 9900").

These trains immediately sold out as, for the first time, trains were no longer viewed as uninteresting, colorless, and moribund devices only good for travel. The streamliner's speed and vibrancy created a renewed interest in trains that continued for another two decades.

As the book, "Streamliners: History Of A Railroad Icon" by author Mike Schafer and Joe Welsh notes, of the 4,700 riders aboard the early Zephyr, nearly 23% took the train simply because of its speed and appeal.

When the United States entered World War II, following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, railroads witnessed record-breaking passenger demand that has never since been duplicated.

Amtrak CF7 #590 shunts cars belonging to the "Auto Train" around the yard in Sanford Florida during March of 1997. This unit began its career as Santa Fe F7A #340-L in 1953. It was rebuilt by the AT&SF as CF7 #2462 in April, 1977 and traded to Amtrak in September, 1984 for an SDP40F. American-Rails.com collection.

Amtrak CF7 #590 shunts cars belonging to the "Auto Train" around the yard in Sanford Florida during March of 1997. This unit began its career as Santa Fe F7A #340-L in 1953. It was rebuilt by the AT&SF as CF7 #2462 in April, 1977 and traded to Amtrak in September, 1984 for an SDP40F. American-Rails.com collection.Don DeNevi notes in his book, "America's Fighting Railroads: A World War II Pictorial History," the year 1942 broke all the records as passenger miles (measured as the number of travelers multiplied by the distance traveled) reached 53 billion.

This number had smashed the previous record by more than 6 billion passenger miles (1920) and was an increase of 80% over 1941. Unfortunately, such copious business levels did not last.

As peace returned in 1945 so too did pre-1941 traffic volumes. With a prosperous economy, Americans traded the train for the automobile or an even faster mode of transportation, airliners (the first jet liner took to the skies in 1958).

As a result, the 1950's were trying times; railroads could not regain public interest despite massive investments in marketing, new equipment, and improved accommodations.

As Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon point out in their book, "New York Central Railroad," the NYC ordered 420 new lightweight, streamlined cars in 1945 to overhaul its passenger fleet. This purchase had joined 300 cars acquired a year earlier.

Combined, the addition of 720 new cars was the largest single order ever placed by an American railroad but did little to attract ridership. The mighty NYC was suffering financially during the 1950's, which led to the poorly conceived merger with the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1968 (Penn Central).

But some, like the Southern Pacific and Milwaukee Road, recognized the signs early and reduced services accordingly.

The industry was further hurt by its own government, which increasingly supported highways and airlines as the 20th century progressed.

Uncle Sam's love/hate relationship with the railroad had been ongoing since the early 1900's when they were heavily regulated in lieu of perceived monopolism; three specific Congressional acts, the Elkins Act of 1903, Hepburn Act of 1906, and Mann-Elkins Act of 1910, considerably expanding the Interstate Commerce Commission's (ICC) power.

Some larger carriers in major metropolitan areas like Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago dealt with the added burden of running commuter trains.

While vital, these operations were woefully unprofitable. However, state public service commissions nearly always denied cutbacks. In the postwar era railroads could no longer afford to subsidize these services through freight earnings alone.

The problem was compounded by the Federal-Aid Highway Act, signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on June 29, 1956. This legislation paved the way for federally funded highways, today's network of Interstates that crisscross the country.

The first signs of relief came in 1958 when Congress eased the process of discontinuing unprofitable intercity trains and Philadelphia offered financial assistance for commuter service by forming the Passenger Service Improvement Corporation.

In spite of this help the heavy losses persisted and only the strongest, like the Santa Fe, Great Northern, Union Pacific, and Southern Railway, could continue maintaining highly quality service throughout the 1960's.

After the Department of Transportation was established on October 15, 1966 the new agency began a serious study of the industry's "passenger problem."

Brian Solomon notes his book, "Amtrak," they concentrated on eliminating this issue while simultaneously sustaining an intercity network. As with everything in Washington, true progress was slow which led to further service declines.

To illustrate how dire the situation had become, just prior to the Great Depression there had been roughly 20,000 passenger trains in operation but by 1970 this number had alarmingly declined to just 420.

Discontinued Services

Abraham Lincoln: Chicago - St. Louis (1935 - 1978)

Ann Rutledge: St. Louis - Kansas City (1937 - 2009)

Arrowhead: Minneapolis - Superior/Duluth (April 15, 1975 - April 30, 1978)

Atlantic City Express: New York City/Philadelphia/Washington, D.C. - Atlantic City (May 21, 1989 - April 1, 1995)

Beacon Hill: Boston - New Haven (1978 - 1981)

Black Hawk (formerly Illinois Central's Land O' Corn): Chicago - Waterloo, Iowa (February 14, 1974 - September 30, 1981)

Blue Ridge: Washington, D.C. - Martinsburg - Parkersburg, West Virginia (May 7, 1973 - September 30, 1981)

Broadway Limited: New York - Chicago (November 14, 1912 - September 9, 1995)

Calumet: Chicago - Valparaiso, Indiana (October 29, 1979 - May 3, 1991)

Campus: Chicago - Champaign, Illinois (November 14, 1971 - March 5, 1972)

Cape Codder: New York City - Hyannis, Massachusetts (July 3, 1986 - September 29, 1996)

Champion: New York City -Miami/St. Petersburg (December 1, 1939 - October 1, 1979)

Chesapeake: Washington, D.C. - Philadelphia (May 1, 1978 - October 29, 1983)

Clockers: Philadelphia - New York (May 1, 1971 - October 28, 2005)

Denver Zephyr: Chicago - Denver (1936 - October 26, 1973)

Desert Wind: Los Angeles - Las Vegas - Ogden (October 28, 1979 - 1981), Los Angeles - Las Vegas - Salt Lake City (1981 - 1983)

El Capitan: Chicago - Los Angeles (February 22, 1938 - April 29, 1973)

Floridian: Chicago - Miami/St. Petersburg (November 14, 1971 - October 9, 1979)

Fort Pitt: Pittsburgh - Altoona (April 26, 1981 - January 30, 1983)

Gulf Breeze: Birmingham - Mobile, Alabama (October 27, 1989 - April 1, 1995)

Gulf Coast Limited: Mobile - New Orleans (April 29, 1984 - March 31, 1997)

Hilltopper: Boston, Massachusetts (South Station) - Petersburg, Virginia - Catlettsburg, Kentucky (June 1, 1977 - October 1, 1979)

Inter-American: Chicago - Laredo, Texas (January 27, 1973 - October 1, 1981)

International: Chicago - Toronto (October 31, 1982 - April 23, 2004)

James Whitcomb Riley: Chicago - Indianapolis - Cincinnati (April 28, 1941 - October 30, 1977)

Kansas City Mule/St. Louis Mule: St. Louis - Kansas City (October 26, 1980 - January 27, 2009)

Kentucky Cardinal: Chicago - Indianapolis - Louisville (December 17, 1999 - July 5, 2003)

Lake Cities: Chicago - Toledo - Detroit (August 3, 1980 - April 26, 2004)

Lake Country Limited: Chicago - Janesville, Wisconsin (April 15, 2000 - September 23, 2001)

Lake Shore: Chicago - Cleveland - New York (May 10, 1971 - January 6, 1972)

Las Vegas Limited: Los Angeles - Los Vegas (May 21, 1976 - August 6, 1976)

Lone Star: Chicago - Dallas - Houston (May 19, 1974 - October 8, 1979)

Loop: Chicago - Springfield (April 27, 1986 - June 28, 1996)

Merchants Limited: Boston - New York (December 14, 1903 - October 28, 1995)

Metroliners: New York - Washington, D.C. (January 16, 1969 - October 27, 2006)

Montrealer/Washingtonian: Washington, D.C. - Montreal (September 30, 1972 - March 31, 1995)

Mountaineer: Norfolk - Cincinnati - Chicago (March 24, 1975 - May 31, 1977)

National Limited: New York - Washington, D.C. - St. Louis - Kansas City (May 1, 1971 - October 1, 1979)

Niagara Rainbow: New York - Buffalo - Detroit (October 31, 1974 - January 31, 1979)

Night Owl: Washington, D.C. - New York - Boston (June 6, 1972 - July 10, 1997)

North Coast Hiawatha: Chicago - Seattle (June 5, 1971 - October 6, 1979)

North Star: Duluth - St. Paul (April 30, 1978 - April 7, 1985)

Pacific International: Seattle - Vancouver (July 17, 1972 - September 30, 1981)

Pioneer: Chicago - Denver - Salt Lake City - Portland - Seattle (June 7, 1977 - May 10, 1997)

Potomac Special/Potomac Turbo: Washington, D.C. - Parkersburg, West Virginia (September 8, 1971 - April 28, 1973)

Prairie Marksman: Chicago - East Peoria, Illinois (August 10, 1980 - October 4, 1981)

River Cities: Kansas City - St. Louis - New Orleans (April 29, 1984 - November 4, 1993)

San Diegan: Los Angeles - San Diego (March 27, 1938 - June 1, 2000)

San Francisco Zephyr: Chicago - San Francisco (June 11, 1972 - July 15, 1983)

Shawnee: Chicago - Carbondale, Illinois (June 3, 1969 - January 2, 1986)

Shenandoah: Washington, D.C. - Parkersburg - Cincinnati (October 31, 1976 - September 30, 1981)

Silver Palm: Miami - Tampa (November 21, 1982 - April 30, 1985)

South Wind: Chicago - Miami (December, 1940 - November 14, 1971)

Spirit Of California: Los Angeles - Sacramento (October 25, 1981 - September 30, 1983)

Spirit Of St. Louis: New York - St. Louis (June 15, 1927 - July, 1971)

State House: Chicago - St. Louis (October 1, 1973 - October 30, 2006)

Super Chief: Chicago - Los Angeles (May 12, 1936 - May 19, 1974)

Texas Chief: Chicago - Houston - Galveston (April 3, 1948 - May 19, 1974)

Three Rivers: New York - Chicago (September 10, 1995 - March 7, 2005)

Twilight Limited: Chicago - Detroit (April 25, 1926 - April 25, 2004)

Willamette Valley: Portland - Eugene (August 3, 1980 - December 31, 1981)

Amtrak E8A #283, E9A #423, and former Penn Central E8A #264 at Rensselaer, New York; July 25, 1976. Carl Sturner photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Amtrak E8A #283, E9A #423, and former Penn Central E8A #264 at Rensselaer, New York; July 25, 1976. Carl Sturner photo. American-Rails.com collection.The issue which finally spurred Congress to action was Penn Central's collapse. When I was in college a few professors highlighted the Penn Central Transportation Company's story.

The lectures were interesting albeit too brief for someone who enjoyed railroad history. At the time, Rush Loving, Jr.'s, "The Men Who Loved Trains," had not yet been published. If so, I am sure it would have been required reading.

Today, many educators, both at the high school and collegiate levels, have likely recommended Loving's title which not only provides an in-depth study of the company's failings but also the intricate politics which pervade large corporations.

It it is an excellent book vividly illustrating how arrogance can destroy even the most powerful companies.

While hubris was a serious issue at Penn Central there were many other factors leading to its downfall. This ill-fated 20,000+ mile monster was officially born at 12:01 AM on Thursday, February 1, 1968 through the merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroads.

It was an immediate disaster that was soon losing more than $1 million a day. Things fell apart so quickly that late in the day on June 21, 1970, Penn Central's board voted to seek voluntary relief from creditors under Section 77 of the federal Bankruptcy Act.

While the "passenger problem" affected the nation, Penn Central's collapse was particularly alarming since it, alone, served the densely populated Northeast.

With its impending shutdown, politicians took notice as the railroad's bankruptcy judge, John P. Fullam, and chief trustee Jervis Langdon, Jr., sought significant service reductions in an effort to eliminate the red ink.

As Langdon stated, "I knew this was a losing game. Hauling passengers made no money. Hauling passengers was killing railroads in the Northeast."

It became so bad that Judge Fullam threatened to discontinue the trains with or without the ICC's authority. At first, politicians wanted to create legislation providing railroads an annual subsidy but this idea failed to garner support.

Following Penn Central's bankruptcy, a bipartisan bill finally passed both houses and the creation of a national carrier was imminent. It was to be called the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPS), or Railpax.

This new, quasi-public entity (a private corporation owned by the federal government) would work by having railroads pay a stipend to join and provide Railpax with hand-me-down equipment in exchange for dropping their remaining trains (Amtrak was paid a total of $197 million, including $40 million from Congress).

One of Amtrak's interesting test-bed models (SNCF Class CC 21000) it put into service during the 1970s, X996 (CC 21003), a French-built electric. It is seen here at Wilmington, Delaware on May 14, 1977.

One of Amtrak's interesting test-bed models (SNCF Class CC 21000) it put into service during the 1970s, X996 (CC 21003), a French-built electric. It is seen here at Wilmington, Delaware on May 14, 1977.Original Network

Northeast Corridor: Boston - Washington, D.C.

"Empire Service": New York - Albany - Buffalo (Via Grand Central Terminal)

New York - Philadelphia - Pittsburgh - Chicago (Via Penn Station)

New York - Kansas City

New York - Miami/Tampa/St. Petersburg

Chicago - Milwaukee/Detroit/Cincinnati/St. Louis

Chicago - Louisville - Birmingham - Miami

Chicago - New Orleans

Chicago - Kansas City - Oklahoma City - Houston

Chicago - Los Angeles

Chicago - Oakland

Chicago - Seattle

Newport News - Charlottesville - Cincinnati

New Orleans - Los Angeles

San Diego - Los Angeles - Seattle

Santa Fe CF7 #2442 leads the Houston Section of Amtrak's "Texas Eagle" through Taylor, Texas, circa 1982. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Santa Fe CF7 #2442 leads the Houston Section of Amtrak's "Texas Eagle" through Taylor, Texas, circa 1982. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Any railroad which chose not to join Railpax by its inauguration date (May 1, 1971) was required to continue running trains until at least 1975.

In the end, every Class I would join except for the Southern Railway (which held out until 1979), Denver & Rio Grande Western (which continued running the Rio Grande Zephyr until 1983), and the Rock Island.

In his book, "Rock Island Requiem," author Greg Schneider notes the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (Rock Island) had been too poor to afford the required entrance fee and continued hosting a sad, dilapidated service informally known as the Peoria Rocket/Quad Cities Rocket until December 31, 1978.

The man ultimately responsible for designing Amtrak's network was Jim McClellan, a then 32-year-old planner from the Federal Railroad Administration (he would later ascend to the top of Norfolk Southern).

He also loved railroads, which made the task of slashing so many once-proud services into a condensed network quite difficult.

Along with help from William Loftus and the consulting firm, McKinsey & Company of Chicago, the group worked out the details inside a small office at L'Enfant Plaza, located near DOT's headquarters.

On October 29, 1970 President Richard Nixon signed into law the Rail Passenger Service Act and the NRPC was officially born.

It was originally designed to provide only intercity services, described as:

"...all rail service other than (A) commuter and other short-haul service in metropolitan and suburban areas, usually characterized by reduced fare, multiple ride and commutation tickets, and by morning and evening peak period operations, and (B) auto-ferry service characterized by transportation of automobiles and their occupants where contracts for such service have been consummated prior to enactment of this Act."

In a last minute change that took place on April 21, 1971, "Railpax" was dropped in favor of "Amtrak," a name conceived by the publication relations company, Lippincott & Marqulies of New York City.

The term came from the words "America" and "Track." This firm also designed the railroad's original "Pointless Arrow" logo.

And so, on May 1, 1971, America entered a new age of rail travel, one provided almost exclusively by the government and not the private sector.

At first, service remained somewhat respectable but, with a lack of adequate funding, things soon declined. The romanticized glory days were over...

To make matters worse, Amtrak was left with many dilapidated stations needing hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in restoration costs.

With such financing not available the carrier sometimes had to vacate larger, better equipped buildings for smaller, inefficient structures. Once grand terminals in cities like Cincinnati (later re-purposed), Detroit, Kansas City (since restored), and Buffalo were simply too rundown for continued use.

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio E7A #101 with an Amtrak consist at Springfield, Illinois in November, 1973. Rick Burn photo.

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio E7A #101 with an Amtrak consist at Springfield, Illinois in November, 1973. Rick Burn photo.Early Years

When Amtrak began on May 1, 1971 eighteen major Class I's joined the carrier. These companies included:

- Baltimore & Ohio

- Burlington Northern

- Chesapeake & Ohio

- Chicago & North Western

- Delaware & Hudson

- Grand Trunk Western

- Gulf, Mobile & Ohio

- Illinois Central

- Louisville & Nashville

- Milwaukee Road

- Missouri Pacific

- Norfolk & Western

- Penn Central

- Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac

- Santa Fe;

- Seaboard Coast Line

- Southern Pacific

- Union Pacific

While railroaders, management, and industry experts understood Amtrak had no hope of ever achieving profitability many politicians erroneously believed it could be attained. This included the Nixon Administration along with Transportation Secretary John A. Volpe.

The latter felt it could break even after just three years and earn a profit thereafter. Of course, this never occurred but Amtrak did streamline the process of purchasing tickets while also lowering prices in an attempt to attract new ridership.

During its first half-year (1971) it handled 6,450,304 travelers, a number which jumped to 15,848,327 in its first full-year (1972).

Its patronage would subsequently increase throughout that decade. Barely a week into operations, Amtrak initiated a new type of operation made available in its chartering, state-sponsored service.

This kicked off on May 10, 1971 when the Lake Shore Limited began running between New York and Chicago via Albany, Buffalo, and Cleveland.

Over the years, the train has carried an on-again/off-again status but when inaugurated it paved the way for future state-sponsored trains which are so common today.

Ridership (1971-1989)

| Fiscal Year | Ridership | Passenger Miles (Millions) | Passenger Revenue (Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 6,450,304 | - | - |

| 1972 | 15,848,327 | 3.038 | $170 |

| 1973 | 16,958,056 | 3.806 | $200 |

| 1974 | 18,670,319 | 4.258 | $256.9 |

| 1975 | 17,269,000 | 3.939 | $252.7 |

| 1976 | 18,046,136 | 4.155 | $277.8 |

| 1977 | 18,961,876 | 4.333 | $310 |

| 1978 | 18,922,652 | 4.029 | $315 |

| 1979 | 21,406,768 | 4.915 | $375 |

| 1980 | 21,219,149 | 4.582 | $428.7 |

| 1981 | 20,609,944 | 4.762 | $612.2 |

| 1982 | 19,042,325 | 4.172 | $630.7 |

| 1983 | 19,038,563 | 4.246 | $664.4 |

| 1984 | 19,943,075 | 4.552 | $758.8 |

| 1985 | 20,776,091 | 4.825 | $825.8 |

| 1986 | 20,327,909 | 5.013 | $861.4 |

| 1987 | 20,414,714 | 5.221 | $847 |

| 1988 | 21,496,303 | 5.678 | $947 |

| 1989 | 21,363,151 | 5.859 | $1.072B |

The above information was gleaned from the book, "Amtrak: An American Story."

Amtrak's financial problems began almost immediately. Since it was designed to achieve profitability, Congress never appropriated an annual subsidy, an issue that continues through the present day.

Despite the persistent threat of shutdown the carrier has continually shown its importance within the national transportation network as ridership has steadily increased since its inception. This was first displayed during the energy crisis of 1973, which brought about a severe fuel shortage.

Then, Amtrak gained a leader with considerable railroad experience in 1975. That individual was Paul Reistrup who replaced Roger Lewis, a former executive at Pan American Railways and General Dynamics.

Reistrup had worked in the passenger departments of both Illinois Central and Baltimore & Ohio, understanding the intricacies of rail travel. During his time, ridership rose by nearly 2 million but even more importantly gross revenues increased by 25%.

In the succeeding years more trains were added, new equipment purchased, and Amtrak, for the first time, began operating trackage it directly owned. The latter became a contentious issue.

After Penn Central's bankruptcy the Northeast Corridor (NEC), the vaunted high-speed route linking Boston with Baltimore, Maryland (originally owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York, New Haven & Hartford), was expected to become property of the Consolidated Rail Corporation, better known as Conrail.

This startup began on April 1, 1976 to preserve freight service in the region. In a move fervently disputed, Conrail was forced to sell the NEC to Amtrak for $87 million.

Today, freight trains can still operate on the line but only at Amtrak's discretion and only during the overnight hours. As Mr. Solomon's book notes, Reistrup had been quite successful at turning around a dying industry.

Unfortunately, he also faced the frustrating political climate of Washington where one never seemed to escape the carousel of criticism and lack of progress. Notwithstanding his successes, Reistrup was condemned for an inability to attain profitability.

Typical of Amtrak's plight, it was forced to cut much needed improvement programs due to funding shortfalls. Its hodgepodge, "Rainbow Fleet" of hand-me-down equipment was largely worn out upon arrival.

Other reductions included canceling the least patronized trains and shelving much-needed Northeast Corridor infrastructure upgrades. To make matters worse, its first new locomotives proved less than satisfactory; General Electric's E-60 (electric) and Electro-Motive's SDP40F (diesel-electric).

The former was specifically designed for the NEC and units began arriving in 1973. They boasted an impressive 6,000 horsepower and were intended to operate at speeds up to 110 mph.

However, yawing problems developed, which stressed the rails and led to derailments. They replaced entirely Electro-Motive's much more reliable "AEM-7's" in 1977/1978 (a number of E-60's were later sold while others were rebuilt during the 1980's).

The SDP40F's carried problems similar to the E-60 by swaying at high speeds, apparently made worse when encountering poor track conditions. Amtrak spent a total of $65 million for its fleet of 150 units, geared for speeds up to 103 mph.

CEOs/Presidents

Roger Lewis: April 28, 1971 - March 1, 1975

Paul Reistrup: March 1, 1975 - April 25 1978

Alan S. Boyd: April 25, 1978 - June 11, 1982

William Graham Claytor Jr.: June 11, 1982 - December 7, 1993

Thomas M. Downs: December 7, 1993 - December 11, 1997

George David Warrington: December 11, 1997 - May 15, 2002

David L. Gunn: May 15, 2002 - November 9, 2005

David J. Hughes: November 9, 2005 - August 29, 2006

Alexander Kummant: August 29, 2006 - November 14, 2008

William Crosbie (Interim): November 14, 2008 - November 25, 2008

Joseph H. Boardman: November 25, 2008 - September 1, 2016

Charles Wickliffe "Wick" Moorman IV: September 1, 2016 – July 12, 2017

Richard H. Anderson: July 12, 2017 - April 14, 2020

William J. Flynn: April 15, 2020 - November 30, 2020

Stephen Gardner: December 1, 2020 - Present

The SDP40F's were intended for use on all non-electrified corridors. At the time, Electro-Motive was the proven and trusted locomotive manufacturer.

Its latest 16-cylinder, model 645E3 prime mover, rated at 3,000 horsepower, was used in the incredibly popular SD40-2 freight model, after which the SDP40F was modeled.

The only differences included a smooth, "cowl" carbody, weight (396,000 pounds compared to the SD40-2's 368,000 pounds), and additional length of 3 feet, 6 inches to carry a steam generator for car heating (prior to the days of HEP).

Unfortunately, engineers could never correct the swaying problem and after several derailments, some railroads began imposing speed restrictions. Finally, in 1977 Amtrak gave up on the SDP40F altogether, trading in the locomotives for the new F40PH.

This model proved so reliable it can still be found in service today (albeit not at Amtrak). As 1980 neared, the carrier further reduced its network by eliminating 12,000 miles of service area to address its funding crisis.

The new decade also brought another problem, an unsympathetic president disinterested in publicly funded rail travel.

Ronald Reagan, elected as the 40th President of the United States in November, 1980, had little interest in Amtrak which he viewed as a waste of federal funding.

He was interested in greatly downsizing the government and that included, in his opinion, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. In a strange turn of events, Reagan appointed a new leader who brought about Amtrak's most prosperous era. On June 11, 1982 William Graham Claytor, Jr. was elected president/CEO.

This legendary railroader was well known for heading the Southern Railway, one of America's most affluent, successful, and profitable railroads. From an early period, excellent management had defined the Southern.

So well in fact that legendary railroader Jim McClellan is quoted as saying the company was a rather boring place to work (from Rush Loving, Jr.'s book, "The Men Who Loved Trains").

As a longtime officer who later worked at Norfolk Southern, McClellan knew of what he spoke. The Southern was a well-oiled machine with precision-like efficiency.

Outwardly, it lived up to its name quite well as the South's largest railroad serving virtually every state below the Mason-Dixon Line and east of the Mississippi River.

It had operated throughout the turbulent 1970's without difficulty and would continue to do so until merging with the Norfolk & Western in 1982 to form today's Norfolk Southern Railway.

Amtrak SDP40F #611 is stopped in Winter Park, Florida with the southbound "Champion" in February, 1980. American-Rails.com collection.

Amtrak SDP40F #611 is stopped in Winter Park, Florida with the southbound "Champion" in February, 1980. American-Rails.com collection.Claytor was an efficiency philosopher and worked his magic at Amtrak, often engaging the Reagan Administration at every turn in an attempt to keep the money flowing.

He was eventually successful on both fronts as new, popular services were inaugurated (like the "Auto Train" and return of the California Zephyr, both in 1983) and public support swelled. Claytor also made use of Amtrak's Congressional allies for financial aid. Without them, it would have certainly been doomed.

Ridership remained relatively stagnate throughout the 1980's, hovering around the 20 million mark. However, Claytor's efforts brought about a significant increase in passenger miles. So, too, did overall revenue; in 1980 it posted earnings of $428.7, a number which had skyrocketed to over $1 billion by 1989.

Claytor was constantly looking for ways to increase revenue. Two noteworthy endeavors included mail/express traffic and an expansion of state-sponsored intrastate/commuter services. In 1984 mail trains returned to the Northeast Corridor followed shortly thereafter by a new fleet of material handling cars (MHC's).

After branching out into the commuter field that decade (following amended legislation enabling it to do so) Amtrak was handling more commuters than long-distance travelers by the 1990's.

Unique Trainsets

Since Amtrak's inception it has fielded some interesting and distinctive trainsets; some have been testbed units while others enjoyed several years of service. The carrier's problem has always been one of funding, poor infrastructure, and dedicated rights-of-way.

Outside of the Northeast Corridor (Boston - Washington, D.C.) it pays freight railroads a stipend to use their property.

These combined issues make it virtually impossible to provide the high-speed services found in countries such as France, Germany or Japan. A brief overview of these models are highlighted here.

TurboTrain

Amtrak's earliest trainset was the TurboTrain, a product of the United Aircraft Corporation.

As a semi-articulated design its heritage can be traced back to the very early streamliners of the 1930's. The first TurboTrain, powered by a 400 horsepower ST-6B gas turbine engine from Pratt & Whitney, was manufactured by Pullman-Standard in Chicago and debuted in May of 1967.

Its first test was carried out in November of that year when it reached a speed of 170.8 mph along the Pennsylvania Railroad between New Brunswick and Trenton, New Jersey.

UAC believed their design, which carried tilting technology, could provide high-speed service without the need for major infrastructure investment (such as electrification).

The first TurboTrain officially entered service on Penn Central in June of 1969. Amtrak had a total of three, which were later upgraded from three to five cars in 1972. They were generally well-liked by travelers but tended to generate a rough ride on poorly maintained track.

This issue, in conjunction with maintenance problems, prevented the TurboTrains from ever reaching their projected top speed of 160 mph. Amtrak pulled them from service in 1976 and they were scrapped by the early 1980's.

Turboliner

The Turboliner was Amtrak's first, dedicated trainset purchased new. Despite problems with the TurboTrain officials still sought a design utilizing gas turbine propulsion. After studying the French SNCF Class T 2000 RTG (Rame à Turbine à Gaz) "Turbotrain," the carrier settled on a model based from this design.

Manufactured by ANF Industrie (Ateliers de Construction du Nord de la France), these trains were the precursor to the highly successful and well known TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) electrified trainsets developed during the 1970s (newer versions of the TGV remain in regular use today).

Unlike the turboprop used in UAC's TurboTrain, Amtrak's Turboliner was equipped with a Turbomeca (another French manufacturer) gas turbine turboshaft traditionally used in helicopters.

During October of 1973 Amtrak began receiving the first of its two "RTG," five-car trainsets (two power cars, two coaches, and a basic bar/grill cafe car); they were equipped with the common European coupler featuring buffers and turnbuckles.

All six units were used exclusively in the Midwest between Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. They remained in service until only 1981.

A variant of the "RTG's" were the similar Turboliners manufactured stateside, under license by Rohr Industries of Chula Vista, California. A total of seven "RTL" sets were produced between 1976 and 1977, carrying several upgrades including standard knuckle-couplers, better forward visibility, and improved handling on poor track.

They were most often assigned to New York's "Empire Corridor/Service" between New York City - Buffalo and occasionally led the Adirondack into Montreal, Quebec. The Rohr Turboliners proved quite reliable, spending nearly 30 years in regular service.

Following a few upgrades, the last of which were completed in 2003, the state of New York sued Amtrak in 2004 over its perceived failure to operate the "Empire Corridor" at 125 mph. After remaining in storage for years the remaining Turboliners were scrapped in 2012.

German Inter-City Express ("ICE Train")

During the 1990's Amtrak imported two European designs for testing as it aimed for high speed service on the Northeast Corridor; one was the Swedish X2000 and the other Germany's "ICE Train."

Officially known as the "German Inter-City Express" it was a product of Siemens and operated between Washington and New Haven, Connecticut during 1993.

Amtrak states the ICE reached a top speed of 165 mph and was occasionally placed on display at various cities throughout the country. Ultimately, the carrier opted against purchasing the ICE Train.

X-2000

The X-2000, or "X-2," was an electrified trainset manufactured by Kalmar Verkstad AB (KVAB) of Kalmar, Sweden. It was shipped to the United States for testing in 1992 and like Germany's "ICE Train" operated on the Northeast Corridor.

Amtrak also passed on this design although former President David Gunn stated it was the best and most logical choice:

"It was reliable, simple, and proven. The reason we got into this mess [regarding Amtrak's purchase of the Acela Express] is because the Canadian government is great at providing financing."

Once again, the failure to purchase the X-2000 likely stemmed from lack of Congressional funding. While the Acela Express proved popular with the public it was plagued with maintenance and reliability issues, including a cracked frame after only a few years of service.

Metroliner

The Metroliner was not necessarily a unique design but the trainsets were a mainstay along the NEC. They were a product of the Budd Company and originally designed for the Pennsylvania Railroad's 11,000-volt, AC Northeast Corridor.

The tube-shaped MU sets first entered service in 1969 during the early Penn Central era but by the time Amtrak launched reliability issues again cropped up, despite their popularity.

The Metroliners were later rebuilt by General Electric with some cars remaining in service for nearly 40 years (no longer powered they were pulled by AEM-7 electrics); the last units made their final runs on October 27, 2006 when they were replaced by the Acela Express.

Claytor was at the helm until 1993; his eleven years of leadership brought Amtrak through its most profitable period.

Columnist Don Phillips, who has written for the Washington Post and covered the railroad industry for decades at Trains Magazine, noted that in 1982 Amtrak's revenues covered only 53% of its total operating costs.

This term describes day-to-day expenses only and does not factor in the additional costs associated with track maintenance/infrastructure improvements.

By 1993 this figure at increased to an astounding 79%. While all of Claytor's initiatives were not realized (Such as the implementation of a 1-cent gasoline tax, the so-called "Ampenny," designed to provide Amtrak with a regular subsidy. He also believed Amtrak could, through continued operational improvements, nearly eliminate its need for federal funding. Unfortunately, this dream was never realized.) the 1990's ushered in the modern era.

By then, freight railroads had strongly rebounded from the dark years of the 1970's thanks to the Staggers Act (which greatly deregulated the industry) and a series of mega-mergers.

In addition, Amtrak's success saw new locomotives purchased for the first time in fifteen years when a large fleet of diesels were ordered from General Electric (the Dash 8-32BWH [or P32BH according to Amrak's lexicon] and "Genesis" series).

At that time it also began testing high speed trainsets (HST's), notably Germany's Intercity City Express (ICE) and Sweden's X2000, for reequipping the electrified Northeast Corridor.

These efforts led to the Acela Express's (a product of Bombardier and Alstom) debut on December 11, 2000. The sets were rated at a top speed of 165 mph, a figure which proved elusive.

Only on a short stretch between Trenton and New Brunswick, New Jersey could they actually attain anywhere near that speed (160 mph).

Along the entire, 457-mile Northeast Corridor the Acela's average was only 68 mph. Still, the trains were loved by the public during their two decades of service.

They are scheduled to be replaced by the latest Avelia Liberty trainsets in 2021 and all will be phased out entirely by 2022. (For Amtrak, the Acela's were never popular due to numerous mechanical and maintenance problems.

Then-president David Gunn stated in the December 2003/January 2004 issue of Mass Transit Magazine Amtrak would have rather purchased Sweden's X2000.)

The new HST's will also be manufactured by Alstom and based from the successful line of TGV and New Pendolino sets. Unfortunately, the NEC's many curves and antiquated electrical grid means the new trains will still fail to offer true high-speed service.

For the many achievements during Claytor's time, Amtrak faced another financial crisis after his departure. It also had to renegotiate its contract with the freight railroads, which expired in 1996.

After slashing more services and working out an agreement with the Class I's, Amtrak managed to weather the worst of these times.

It continued to carry a business-like approach under President Thomas Downs, who continued Clatyor's legacy. While Downs was able to secure federal funding through 2002 he was subsequently replaced by George Warrington in December of 1998.

The idea of turning Amtrak into a profitable corporation "above the rail" (i.e., covering all operating expenses except track maintenance and capital improvements) was consistently pushed by Warrington and a stipulation of Amtrak's latest 5-year Congressional subsidy period.

This, again, proved unrealistic although it continued showing strong ridership as a new century dawned.

Into the 21st century, Amtrak entered a new age with a new livery. Just before the Acela Express launched the long-awaited dream of continuous electrified service into Boston became a reality in January of 2000.

Train Routes

Services

Amtrak California

Auto Train

Turboliner

TurboTrain

Defunct Trains

Other Trains

Adirondack

California Zephyr

Capitol Limited

Cardinal

Carolinian

Cascades

City of New Orleans

Coast Starlight

Downeaster

Empire Service

Ethan Allen Express

Heartland Flyer

Maple Leaf

Missouri River Runner

Northeast Regional

Palmetto

Pennsylvanian

San Joaquin

Southwest Chief

Texas Eagle

Equipment

1993 Tests

More Reading

Modern Era

Amtrak's history has been an ebb and flow affair of success and setback. While it has proven travelers will still take the train in spite of today's fast-paced world, funding shortfalls preclude serious investment and greater ridership.

While ignorant politicians remain in control of the railroad's financial outlook, loudly proclaiming it should be a self-sufficient entity, there is little hope for indefinite service improvements.

What many have never understood is that railroads have largely never profited from hauling passengers; only during the 19th and early 20th centuries did such business generate any type of positive revenue.

In the post-depression era, railroads subsidized the service through freight revenue. However, after World War II this became increasingly difficult. As service declined and Penn Central collapsed, Washington was forced to create Amtrak.

Unless our lawmakers provides annual funding (such as the small gasoline tax proposed by Graham Claytor) the merry-go-round will continue indefinitely.

With Class I's having no interest in hosting its trains (which lead to constant delays) the only answer is to build (or rebuild) dedicated corridors directly-owned by Amtrak for greater ridership and high-speed service.

It seems, though, this scenario is also unlikely given decades of infrastructure neglect. Don Phillips has addressed these issues and many others related to Amtrak. In an article from the May, 2010 issue of Trains Magazine he poignantly stated how political ignorance has gravely hurt any chance for true change:

"I've learned a lesson about the new 'high speed rail' movement. We should never assume that even the most enthusiastic new supporter of high speed knows much about railroads or railroad history. It would be to their advantage to learn a few things."

"Even some of the most responsible and enthusiastic high speed advocates don't seem to understand that the first steps towards faster trains will involve merely bringing us back to what railroading was doing in the 1930s.

They talk as if 90 or 110 mph will be a great leap forward, but in reality, steam locomotives running on jointed rail did the very same thing every day back then."

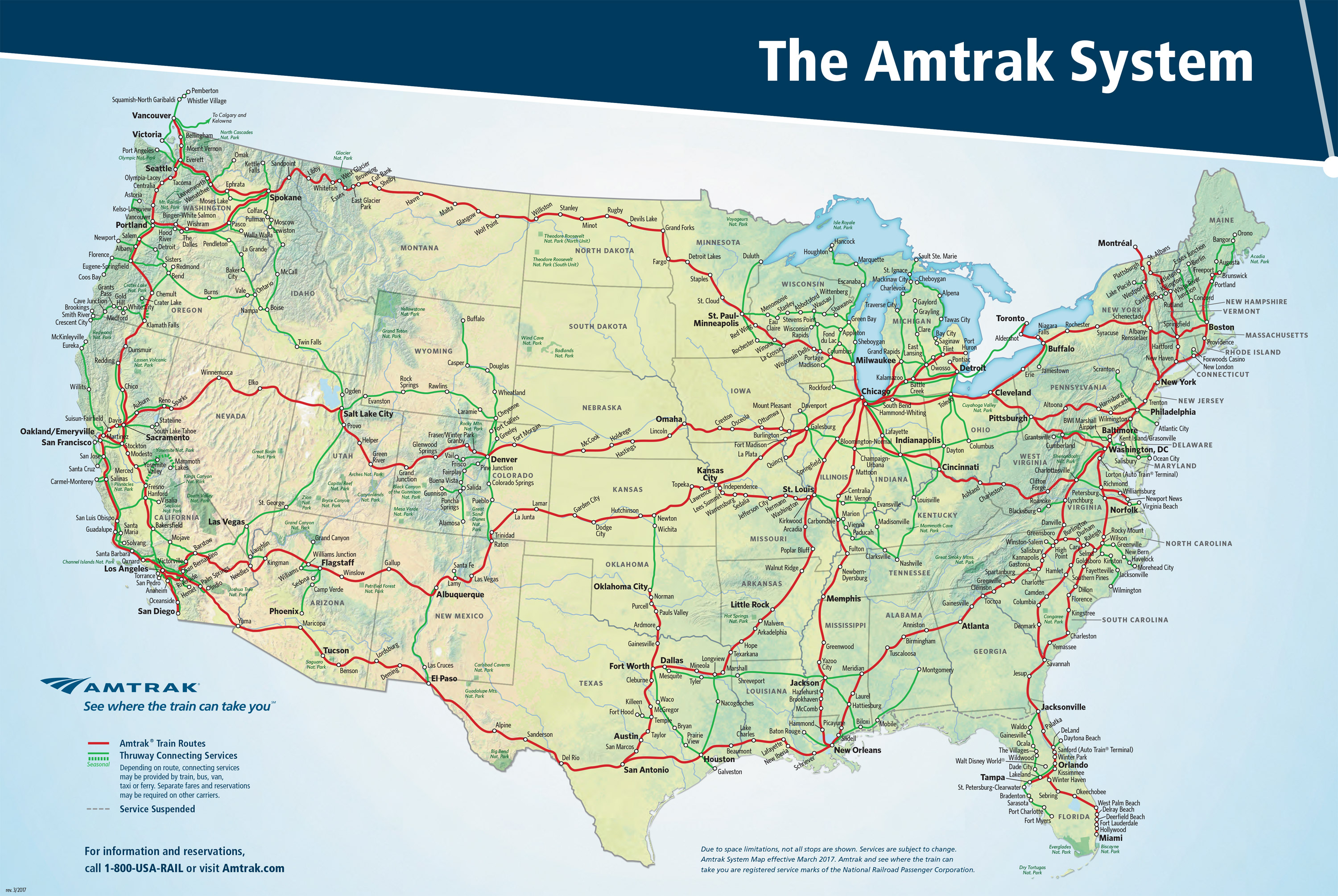

System Map

As Amtrak's ridership continues to grow, breaking 31 million for the first time in 2012, other modes of rail transportation have also increased in popularity. Light rail transit (or LRT) is the most noteworthy, a type of reincarnated interurban/streetcar operation.

Many have popped up in cities large and small throughout the country as a cheaper and more efficient alternative to highways; they not only reduce wear on city streets but also reduce congestion. In addition, since they produce few, if any, emissions they are environmentally friendly.

In some places, LRT's are a nostalgic look at the classic trolley and marketed as such. Locations where these can now be found include Charlotte, North Carolina; Denver, Colorado; Seattle, Washington; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Norfolk, Virginia. A few cities with future plans to add LRT include Kansas City, Kansas and Austin, Texas. If you are interested in keeping up-to-date on the latest LRT news and projects, please visit Mass Transit's website.

Ridership, 1990-2019 (Latest Year Available)

| Fiscal Year | Ridership | Passenger Miles (Millions) | Passenger Revenue (Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 22,186,300 | 6.057 | $878 |

| 1991 | 22,062,425 | 6.273 | $908 |

| 1992 | 21,345,247 | 6.091 | $872 |

| 1993 | 22,065,869 | 6.199 | $885 |

| 1994 | 21,837,626 | 5.921 | $827 |

| 1995 | 20,726,490 | 5.545 | $827 |

| 1996 | 19,605,398 | 5.050 | $850 |

| 1997 | 20,190,450 | 5.166 | $916 |

| 1998 | 21,094,165 | 5.304 | $946 |

| 1999 | 21,508,694 | 5.330 | $1.003 billion |

| 2000 | 22,517,264 | 5.498 | $1.088 billion |

| 2001 | 23,493,805 | 5.559 | $1.178 billion |

| 2002 | 23,406,597 | 5.468 | $1.250 billion |

| 2003 | 24,028,119 | 5.503 | $1.183 billion |

| 2004 | 25,053,564 | 5.558 | $1.231 billion |

| 2005 | 25,374,998 | 5.420 | $1.216 billion |

| 2006 | 24,392,065 | 5.362 | $1.371 billion |

| 2007 | 25,847,503 | 5.652 | $1.519 billion |

| 2008 | 28,716,403 | 6.160 | $1.732 billion |

| 2009 | 27,166,936 | 5.898 | $1.599 billion |

| 2010 | 28,716,804 | 6.332 | $1.743 billion |

| 2011 | 30,200,000 | 6.568 | $2.683 billion |

| 2012 | 31,200,000 | 6.752 | $2.866 billion |

| 2013 | 31,600,000 | 7.283 | $2.990 billion |

| 2014 | 30,900,000 | 6.675 | $3.236 billion |

| 2015 | 30,900,000 | 6.536 | $3.211 billion |

| 2016 | 31,300,000 | 6.520 | $3.200 billion |

| 2017 | 31,700,000 | 6.563 | $3.306 billion |

| 2018 | 31,700,000 | 6.361 | $3.387 billion |

| 2019 | 32,500,000 | 6.420 | $3.506 billion |

The above information was gleaned from official Amtrak annual reports, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, and the book, "Amtrak: An American Story."

More than ten years ago, Amtrak experienced another roller-coaster ride when a report came out in December, 2007 proposing $357 billion towards passenger rail improvements over the following four decades. It would have been a jointly funded endeavor at the federal and state level.

Then, during the spring of 2009, newly elected President Barack Obama appropriated $8 billion towards the development of ten high speed rail corridors ranging from 100 to 600 miles in length.

Unfortunately, both the president's plan and the 2007 report never gained serious interest leaving the passenger train in limbo once more.

One of Amtrak's popular bilevel "Superliner" sleepers at Reno, Nevada in June, 2000. This car was part of the original Superliner I fleet (284 cars) manufactured by Pullman-Standard between 1975-1981 and based from the Santa Fe's Hi-Level cars (Budd) used on its "El Capitan." Bombardier Transportation would later build another 195 "Superliner II" cars between 1991-1996. American-Rails.com collection.

One of Amtrak's popular bilevel "Superliner" sleepers at Reno, Nevada in June, 2000. This car was part of the original Superliner I fleet (284 cars) manufactured by Pullman-Standard between 1975-1981 and based from the Santa Fe's Hi-Level cars (Budd) used on its "El Capitan." Bombardier Transportation would later build another 195 "Superliner II" cars between 1991-1996. American-Rails.com collection.Historically, Republicans have been less receptive in utilizing federal funds towards infrastructure improvements. However, Democrats have also failed, particularly during President Obama's first term (when they controlled the White House and Congress) to radically change Amtrak's outlook for the better.

With Republicans currently in control it appears the carrier will continue limping along, garnering only enough funding to remain operable on a year-to-year basis.

Diesel Roster

| Road Number | Builder | Model Type | Date Built | Notes/History |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-207 | GE | P42DC | 8/1996-12/2001 | (Purchased New) |

| 1, 3 | EMD | SW8 | 12/1953 | New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal #1, #3 |

| 5 | GE | 65-Tonner | 6/1943 | U.S. Army #7179 |

| 6 | GE | 65-Tonner | 4/1942 | Weldon Springs Ordinance Works |

| 7, 77 | GE | 45-Tonner | 5/1941 | Kingsbury Ordinance Works |

| 9 | GE | 65-Tonner | 4/1942 | Weldon Springs Ordinance Works |

| 1000, 1100 | GE | 80-Tonner | 11/1951-1/1952 | U.S. Army #1602, #1600 |

| 44, 46-47, 59, 62 | Alco | RS1 | 7/1945-3/1950 | Washington Terminal #44, #46-47. #59, #62 |

| 100 | EMD | F7A | 5/1949 | Northern Pacific #6502C |

| 100 | Alco | RS3 | 8/1950 | New York Central #8223 |

| 101 | EMD | F7A | 4/1949 | Northern Pacific #6508C |

| 101 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1951 | New York Central #8232 |

| 102 | EMD | F7A | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6509A |

| 102 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1951 | New York Central #8233 |

| 103 | EMD | F7A | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6509C |

| 103 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1951 | New York Central #8236 |

| 104 | EMD | F7A | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6511A |

| 104 | Alco | RS3M | 5/1951 | New York Central #8246 (Re-powered With EMD 567) |

| 105 | EMD | F7A | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6511C |

| 105 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1951 | New York Central #8258 |

| 106 | EMD | F7A | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6512A |

| 106 | Alco | RS3M | 6/1951 | New York Central #8263 (Re-powered With EMD 567) |

| 107 | EMD | F7A | 2/1950 | Northern Pacific #6513A |

| 107 | Alco | RS3M | 10/1951 | New York Central #8282 (Re-powered With EMD 567) |

| 108-109 | Alco | RS3 | 9/1951, 4/1952 | New York Central #8302, #8316 |

| 110 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6446 |

| 110 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1952 | New York Central #8220 |

| 111 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6447 |

| 111 | Alco | RS3 | 5/1952 | New York Central #8340 |

| 112 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6448 |

| 112 | Alco | RS3 | 9/1953 | New York Central #8348 |

| 113 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6449 |

| 113 | Alco | RS3 | 12/1955 | Pennsylvania #8602 |

| 114 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6450 |

| 114 | Alco | RS3 | 12/1955 | Pennsylvania #8604 |

| 115 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6451 |

| 115 | Alco | RS3 | 11/1953 | Pennsylvania #8436 |

| 116 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6453 |

| 116 | Alco | RS3 | 11/1951 | Pennsylvania #8828 |

| 117 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6454 |

| 117 | Alco | RS3 | 11/1953 | Pennsylvania #8441 |

| 118 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #6455 |

| 118 | Alco | RS3 | 11/1953 | Pennsylvania #8442 |

| 119 | EMD | FP7 | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #6456 |

| 119 | Alco | RS3 | 6/1952 | Pennsylvania #8456 |

| 120 | EMD | FP7 | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #6457 |

| 120 | Alco | RS3 | 6/1952 | Pennsylvania #8458 |

| 121 | EMD | FP7 | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #6458 |

| 121 | Alco | RS3 | 6/1952 | Pennsylvania #8465 |

| 122 | EMD | FP7 | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #6459 |

| 122 | Alco | RS3 | 8/1950 | New Haven #523 |

| 123 | EMD | FP7 | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #6461 |

| 123 | Alco | RS3 | 8/1950 | New Haven #527 |

| 124-136 | Alco | RS3 | 6/1951-10/1951 | New York Central #8252-8255, #8264, #8268-8270, #8275, #8277, #8280, #8285, #8291 |

| 137-139, 141, 143-144 | Alco | RS3 | 8/1950-1/1952 | New Haven #524, #529, #533, #539, #553-554 |

| 140, 142 | Alco | RS3 | 4/1951, 7/1952 | Pennsylvania #8912, #8479 |

| 150 | EMD | F7B | 1/1953 | Great Northern #462C |

| 151 | EMD | F7B | 1/1953 | Great Northern #464B |

| 152 | EMD | F7B | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6510-B |

| 153 | EMD | F7B | 9/1949 | Northern Pacific #6511-B |

| 154 | EMD | F7B | 2/1950 | Northern Pacific #6513-B |

| 155 | EMD | F3B | 1/1947 | Northern Pacific #6505-C |

| 156 | EMD | F3B | 4/1947 | Northern Pacific #6506-C |

| 160 | EMD | F7B | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #8290 |

| 161 | EMD | F7B | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #8291 |

| 162 | EMD | F7B | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #8294 |

| 163 | EMD | F7B | 2/1953 | Southern Pacific #8296 |

| 164 | EMD | F7B | 3/1953 | Southern Pacific #8303 |

| 192-199 | GMDD | GP40TC | 11/1966-12/1968 | Canadian Pacific #600-607/GO Transit #500-507, #9800-9807 |

| 200 | EMD | E8A | 9/1950 | Baltimore & Ohio #90A/#1439 |

| 201 | EMD | E8A | 9/1950 | Baltimore & Ohio #94A/#1443 |

| 202 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #26/#1446 |

| 203 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #26A/#1447 |

| 204 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #28/#1448 |

| 205 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #28A/#1449 |

| 206 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #30/#1450 |

| 207 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #30A/#1451 |

| 208 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #32/#1452 |

| 209 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Baltimore & Ohio #32A/#1453 |

| 210 | EMD | E8A | 9/1950 | Baltimore & Ohio #92/#1440 |

| 211 | EMD | E8A | 11/1951 | Chesapeake & Ohio #4013/Baltimore & Ohio #1467 |

| 212 | EMD | E8A | 1/1952 | Chesapeake & Ohio #4026 |

| 213 | EMD | E8A | 11/1949 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1001 |

| 214 | EMD | E8A | 11/1949 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1005 |

| 215 | EMD | E8A | 2/1952 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1006 |

| 216 | EMD | E8A | 2/1952 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1007 |

| 217 | EMD | E8A | 2/1952 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1008 |

| 218 | EMD | E8A | 8/1952 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1010 |

| 219 | EMD | E8A | 8/1952 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1011 |

| 220 | EMD | E8A | 9/1953 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1012 |

| 221 | EMD | E8A | 9/1953 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1013 |

| 222 | EMD | E8A | 9/1953 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1014 |

| 223 | EMD | E8A | 10/1953 | Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac #1015 |

| 224 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Louisville & Nashville #794 |

| 225 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Louisville & Nashville #795 |

| 226 | EMD | E8A | 2/1950 | St. Louis-San Francisco #2007 |

| 227 | EMD | E8A | 2/1950 | St. Louis-San Francisco #2014 |

| 200-229 | EMD | F40PH | 3/1976-5/1976 | (Purchased New) |

| 230 | EMD | E8A | 12/1952 | Fort Worth & Denver (Burlington) #9981A |

| 231 | EMD | E8A | 12/1952 | Fort Worth & Denver (Burlington) #9981B |

| 231 | EMD | FL9 | 10/1956 | New Haven #2001 |

| 230-269 | EMD | F40PHR | 7/1977-1/1978 | (Purchased New) |

| 232 | EMD | E8Am | 11/1939 | Rebuilt From E3A |

| 232 | EMD | FL9 | 8/1957 | New Haven #2004 |

| 233 | EMD | E8A | 6/1946 | Atlantic Coast Line #532 (2nd) |

| 233 | EMD | FL9 | 8/1957 | New Haven #2006 |

| 234 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #544 |

| 234 | EMD | FL9 | 9/1957 | New Haven #2008 |

| 235 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #545 |

| 235 | EMD | FL9 | 9/1957 | New Haven #2009 |

| 236 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #546 |

| 236 | EMD | FL9 | 9/1957 | New Haven #2010 |

| 237 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #548 |

| 237 | EMD | FL9 | 9/1957 | New Haven #2013 |

| 238 | EMD | E8A | 3/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #549 |

| 238 | EMD | FL9 | 9/1957 | New Haven #2014 |

| 239 | EMD | E8A | 3/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #550 |

| 239 | EMD | FL9 | 10/1957 | New Haven #2016 |

| 240 | EMD | E8A | 3/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #551 |

| 240 | EMD | FL9 | 10/1957 | New Haven #2021 |

| 241 | EMD | E8A | 3/1950 | Atlantic Coast Line #552 |

| 241 | EMD | FL9 | 10/1957 | New Haven #2025 |

| 242 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Atlantic Coast Line #553 |

| 242 | EMD | FL9 | 11/1957 | New Haven #2029 |

| 243 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Atlantic Coast Line #554 |

| 243/730 | EMD | SW1 | 5/1949 | New York Central #599 |

| 244 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Atlantic Coast Line #555 |

| 244/731 | EMD | SW1 | 6/1949 | New York Central #602 |

| 245 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Atlantic Coast Line #556 |

| 245/732 | EMD | SW1 | 5/1939 | New York Central #605 |

| 246 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Seaboard Air Line #3050 |

| 246/733 | EMD | SW1 | 5/1939 | New York Central #616 |

| 247 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Seaboard Air Line #3051 |

| 247/734 | EMD | SW1 | 5/1941 | New York Central #628 |

| 248 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Seaboard Air Line #3052 |

| 248/735 | EMD | SW1 | 5/1941 | New York Central #629 |

| 249 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Seaboard Air Line #3053 |

| 249/736 | EMD | SW1 | 1/1942 | New York Central #651 |

| 250 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Seaboard Air Line #3054 |

| 250/737 | EMD | SW1 | 1/1942 | New York Central #653 |

| 251 | EMD | E8A | 11/1952 | Seaboard Air Line #3055 |

| 251/738 | EMD | SW1 | 11/1950 | Pennsylvania #9422 |

| 252 | EMD | E8A | 12/1952 | Seaboard Air Line #3056 |

| 252/739 | EMD | SW1 | 11/1950 | Pennsylvania #9423 |

| 253 | EMD | E8A | 12/1952 | Seaboard Air Line #3057 |

| 253/740 | EMD | SW1 | 11/1950 | Pennsylvania #9428 |

| 254 | EMD | E8A | 12/1952 | Seaboard Air Line #3059 |

| 254/741 | EMD | SW1 | 7/1948 | Pennsylvania #9150 |

| 255 | EMD | E8A | 6/1953 | New York Central #4020 |

| 255/742 | EMD | SW1 | 7/1948 | Pennsylvania #9143 |

| 256 | EMD | E8A | 6/1951 | New York Central #4036 |

| 256/743 | EMD | SW1 | 8/1950 | Pennsylvania #9399 |

| 257 | EMD | E8A | 6/1951 | New York Central #4038 |

| 257/744 | EMD | SW1 | 7/1948 | Pennsylvania #9145 |

| 258 | EMD | E8A | 8/1951 | New York Central #4040 |

| 258/745 | EMD | SW1 | 4/1949 | Pennsylvania #5987 |

| 259-276 | EMD | E8A | 8/1951-4/1952 | New York Central #4041, #4043-4049, #4051-4061 |

| 270-279 | EMD | F40PH | 11/1977-1/1978 | (Purchased New) |

| 280-299 | EMD | F40PHR | 4/1978-7/1979 | (Purchased New) |

| 300-309 | EMD | F40PH | 4/1979-5/1979 | (Purchased New) |

| 310-331 | EMD | F40PHR | 7/1979-8/1980 | (Purchased New) |

| 332-359 | EMD | F40PH | 8/1980-12/1980 | (Purchased New) |

| 277-324 | EMD | E8A | 4/1950-11/1952 | Pennsylvania #5790-A, #5792A, #5769A, #5701A, #5703A-5710A, #5804A, #5802A-5803A, #5884A, #5886A-5892A, #5892, #5893A, #5894-5899, #5700A, #5801A, #5902-5904, #5806A-5807A, #5808-5810, #5711A-5716A, #5835, #5839 |

| 325-331 | EMD | E8A | 5/1950-4/1953 | Union Pacific #926A, #929A, #931A-933A, #938A-939A |

| 332-352 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950-10/1952 | Burlington #9940B-9941B, #9943B, #9937B, #9941A-9949A, #9944B, #9946B-9948B, #9964-9966, #9968, #9969 |

| 360-409 | EMD | F40PHR | 12/1980-2/1988 | (Purchased New) |

| 367-368 | EMD | E8A | 5/1950, 8/1950 | Ex-#325, #326 |

| 370-374 | EMD | E8B | 6/1950-4/1953 | Union Pacific #927B, #932B, #940B-941B, #948B |

| 376-377 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Ex-#116, #117 |

| 400-412 | EMD | E9A | 5/1955-6/1956 | Baltimore & Ohio #34, #36, #38; Seaboard Air Line #3060; Milwaukee Road #200A, #200C, #201A, #201C, #205A, #205C; Union Pacific #904A, #907A |

| 413 | EMD | E8A | 4/1950 | Burlington #9944B |

| 414-435 | EMD | E9A | 5/1954-8/1961 | Union Pacific #909A-914A, #943A-948A, #952A-953A, #955A-957A |

| 436 | EMD | E8A | 5/1952 | Illinois Central #4029 |

| 437 | EMD | E8A | 5/1950 | Ex-#325 |

| 437 | EMD | E8A | 11/1949 | Ex-#213 |

| 438 | EMD | E8A | 8/1950 | Ex-#326 |

| 438 | EMD | E8A | 2/1952 | Ex-#215 |

| 439 | EMD | E8A | 2/1952 | Ex-#216 |

| 440 | EMD | E8A | 9/1953 | Ex-#220 |

| 441 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Ex-#224 |

| 442 | EMD | E8A | 5/1951 | Ex-#225 |

| 443 | EMD | E8A | 2/1950 | Ex-#226 |

| 444 | EMD | E8Am | 3/1953 | Ex-#232 |

| 445 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Ex-#236 |

| 446 | EMD | E8A | 10/1950 | Ex-#249 |

| 446 | EMD | E9B | 5/1954 | Union Pacific #952B |

| 447 | EMD | E8A | 5/1952 | Ex-#277 |

| 448 | EMD | E8A | 9/1952 | Ex-#280 |

| 449 | EMD | E8A | 3/1951 | Ex-#302 |

| 450 | EMD | E8A | 8/1951 | Ex-#259 |

| 450-470 | EMD | F59PHI | 4/1998-11/1998 | (Purchased New) |

| 450 | EMD | E9B | 4/1956 | Milwaukee Road #202B |

| 451 | EMD | E9B | 4/1956 | Milwaukee Road #204B |

| 452 | EMD | E8A | 4/1952 | Ex-#273 |

| 452 | EMD | E9B | 4/1956 | Milwaukee Road #205B |

| 453-455 | EMD | E9B | 5/1954-11/1962 | Union Pacific #911B-912B, #951B |

| 456 | EMD | E8A | 4/1950 | Ex-#295 |

| 456 | EMD | E9B | 5/1954 | Union Pacific #952B |

| 457 | EMD | E8A | 9/1952 | Ex-#307 |

| 457 | EMD | E9B | 5/1954 | Union Pacific #954B |

| 458 | EMD | E8A | 3/1951 | Ex-#310 |

| 458-460 | EMD | E9B | 6/1954 | Union Pacific #956B-958B |

| 461 | EMD | E8A | 11/1952 | Ex-#322 |

| 461 | EMD | E9B | 6/1954 | Union Pacific #959B |

| 462 | EMD | E8A | 3/1953 | Ex-#328 |

| 462 | EMD | E9B | 5/1955 | Union Pacific #961B |

| 463 | EMD | E8A | 1/1950 | Ex-#332 |

| 463 | EMD | E9B | 6/1955 | Union Pacific #963B |

| 464 | EMD | E8A | 3/1950 | Ex-#334 |

| 464 | EMD | E9B | 6/1955 | Union Pacific #964B |

| 465 | EMD | E8A | 8/1950 | Ex-#345 |

| 465-467 | EMD | E9B | 6/1955-9/1955 | Union Pacific #965B-967B |

| 468 | EMD | E8A | 5/1950 | Ex-#367 |

| 468 | EMD | E9B | 10/1955 | Union Pacific #970B |

| 469 | EMD | E8A | 8/1950 | Ex-#368 |

| 469-470 | EMD | E9B | 10/1955 | Union Pacific #971B-972B |

| 470 | EMD | Fuel Car | 5/1955 | Ex-E8A #400 |

| 471-472 | EMD | E9B | 2/1956, 4/1956 | Milwaukee Road #201B, #203B |

| 473-476 | EMD | E9B | 5/1954-4/1956 | Ex-#450-452, #457 |

| 480-491 | EMD | FL9 | 10/1956-11/1957 | Ex-#231-242 |

| 492-493 | EMD | FP7 | 2/1953 | Ex-#376, #377 |

| 495-499 | EMD | E8A | 1/1951-10/1952 | Ex-#284, #288, #305, #315, #317 |

| 500-649 | EMD | SDP40F | 6/1973-8/1974 | (Purchased New) |

| 500-519 (2nd) | GE | B32-8WH (Dash32-BWH) | 12/1991 | (Purchased New) |

| 530-539 | EMD | MP15DC | 5/1975 | Pittsburgh & Lake Erie #1585-1586, #1589-1595, #1597 |

| 540-541 | EMD | SW1500 | 9/1973 | Penn Central #9563, #9572 |

| 569 | EMD | SW1001 | 11/1973 | Reading #2602 |

| 570-579 | MPI | GP15D | 10/2004-12/2004 | (Acquired New) |

| 590, 592-593 | MPI | MP14B | 2010-8/2013 | (Acquired New) |

| 591 | MPI | MP21B | 2010 | (Acquired New) |

| 597, 599 | NRE | 2GS12B | 2014-2015 | (Acquired New) |

| 700-724 (1st) | GE | P30CH "Pooch" | 1975-1976 | (Purchased New) |

| 720 | EMD | GP38-3 | 4/1967 | Clinchfield GP38 #2002 |

| 721 | EMD | GP38-3 | 10/1967 | Baltimore & Ohio GP38 #3805 |

| 722 | EMD | GP38-3 | 11/1967 | Chesapeake & Ohio GP38 #3874 |

| 723 | EMD | GP38-3 | 8/1969 | Penn Central GP38 #7758 |

| 724 | EMD | GP38-3 | 6/1970 | Louisville & Nasvhille GP38 #4003 |

| 700-717 (2nd) | GE | P32AC-DM | 4/1995-3/1998 | (Purchased New) |

| 746 | Alco | S2 | 7/1943 | U.S. Army #7110 |

| 747 | EMD | SW8 | 2/1953 | New York Central #9623 |

| 748 | EMD | SW8 | 2/1953 | New York Central #9625 |

| 749 | EMD | SW8 | 9/1951 | Lehigh Valley #267 |

| 750 | EMD | SW8 | 12/1952 | Lehigh Valley #275 |

| 760 | EMD | GP7 | 1/1952 | St. Louis-San Francisco #610 |

| 761 | EMD | GP7 | 2/1952 | St. Louis-San Francisco #621 |

| 762 | EMD | GP7 | 9/1950 | Wabash #452 |

| 763 | EMD | GP9 | 1/1954 | Union Pacific #208 |

| 764 | EMD | GP9 | 4/1954 | Union Pacific #185 |

| 765-768 | EMD | GP9 | 1/1954 | Union Pacific #241, #207, #242, #234 |

| 769-770 | EMD | GP9 | 8/1952, 3/1957 | Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha #160; Chicago & North Western #1726 |

| 771 | EMD | GP9 | 2/1953 | Louisville & Nashville #432 |

| 772 | EMD | GP7 | 9/1950 | Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis #710 |

| 773 | EMD | GP7 | 7/1951 | Quebec North Shore & Labrador #100 |

| 774-776 | EMD | GP7 | 8/1950-2/1953 | Wasbash #451, #461; Union Pacific #702 |

| 777 | EMD | GP7 | 2/1953 | Union Pacific #704 |

| 778 | EMD | GP7 | 6/1953 | Union Pacific #710 |

| 779 | EMD | GP7 | - | - |

| 780 | EMD | GP7 | 3/1950 | Chicago & Eastern Illinois #210 |

| 781, 783 | EMD | GP7 | 1/1950, 7/1950 | Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis #703; Rock Island #433 |

| 782 | EMD | GP7 | 2/1950 | Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis #705 |

| 790-791 | NRE | SW1000R | 2/1952 | Missouri-Kansas-Texas SW9 #1228, #1230 |

| 792-794 | NRE | SW1000R | 12/1952-1/1953 | Montour Railroad SW9 #73, #78, #83 |

| 795 | NRE | SW1000R | 11/1954 | Milwaukee Road SW1200 #2028 |

| 796-798 | NRE | SW1000R | 3/1952 | Pittsburgh & Lake Erie SW9 #8959, #8957, #8955 |

| 799 | NRE | SW1000R | 3/1952 | Baltimore & Ohio SW9 #593 |

| 800-845 | GE | P40-8 "Genesis" | 3/1993-3/1994 | (Purchased New) |

| 300–424 | Siemens | ALC-42 | 2018-Present | (Purchased New) |

| 4601–4633 | Siemens | SC-44 | 2016-Present | (Purchased New) |

Self-Propelled Rail Car Roster

| Road Number | Builder | Model Type | Date Built | Notes/History |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-20 | Budd | RDC-1 | 4/1952-3/1953 | New Haven #36-39, #41, #44, #48, #21, #23, #32, #34 |

| 27-28 | Budd | RDC "Roger Williams" | 1956 | New Haven |

| 29 | Budd | RDC | 1957 | New Haven #162 |

| 30 | Budd | RDC-2 | 1/1955 | Northern Pacific #B-30 |

| 31-32 | Budd | RDC-2 | 5/1950, 7/1950 | Western Pacific #375-376 |

| 34 | Budd | RDC-2 | 7/1951 | New York Central #M-480 |

| 36 | Budd | RDC-2 | 5/1952 | New Haven #121 |

| 38-39 | Bombardier | LRC-2 | 2/1980-6/1980 | (Leased) |

| 40-42 | Budd | RDC-3 | 12/1952-9/1956 | Northern Pacific #B40-B42 |

| 43 | Budd | RDC-3 | 7/1956 | Great Northern #2350 |

| 50-53 | United Aircraft/Pullman | TurboTrain | 1967 | (Purchased New) |

| 54-57 | United Aircraft/Milwaukee Road | TurboTrain | 5/1968-7/1968 | Canadian National #127-128, #152-153 |

| 58-69 | ANF Industrie | RTG Turboliner | 7/1973-2/1975 | (Purchased New) |

| 150-163 | Rohr | RTL Turboliner | 1976 | (Purchased New) |

Electric Locomotive Roster

| Road Number | Builder | Model Type | Date Built | Notes/History |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500-507 | GE | E-44 | 5/1963 | Pennsylvania #4463-4465, #4460, #4462, #4458, #4459, #4461 |

| 600 | GE | E60MA | 2/1976 | Ex-E60CH #974 |

| 601 | GE | E60MA | 10/1975 | Ex-E60CP #956 |

| 602 | GE | E60MA | 3/1976 | Ex-E60CH #975 |

| 603 | GE | E60MA | 6/1976 | Ex-E60CH #964 |

| 604 | GE | E60MA | 11/1975 | Ex-E60CH #957, nee-#951 |

| 605 | GE | E60MA | 6/1975 | Ex-E60CH #965 |

| 606 | GE | E60MA | 3/1976 | Ex-E60CH #970 |

| 607 | GE | E60MA | 3/1976 | Ex-E60CH #969 |

| 608 | GE | E60MA | 11/1975 | Ex-E60CP #952 |

| 609 | GE | E60MA | 11/1975 | Ex-E60CP #951, nee-#957 |

| 610 | GE | E60MA | 11/1975 | Ex-E60CP #955 |

| 620-621 | GE | E60 | 12/1974, 11/1975 | Ex-E60CP #950, #953 |

| 650-664 | Bombardier/Alstom | HHP-8 | 1998-2001 | (Purchased New) |

| 600-670 | Siemens | ACS-64 | 2/2014-7/2016 | (Purchased New) |

| 900 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 3/1940 | Pennsylvania #4892 |

| 901 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 4/1940 | Pennsylvania #4897 |

| 902 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 5/1940 | Pennsylvania #4899 |

| 903 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 5/1940 | Pennsylvania #4900 |

| 904 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 5/1940 | Pennsylvania #4901 |

| 905 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 5/1940 | Pennsylvania #4902 |

| 906 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 5/1940 | Pennsylvania #4903 |

| 907 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 6/1940 | Pennsylvania #4906 |

| 908 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 8/1940 | Pennsylvania #4908 |

| 909 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 8/1940 | Pennsylvania #4909 |

| 910 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 12/1941 | Pennsylvania #4910 |

| 911 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 1/1942 | Pennsylvania #4911 |

| 912 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 1/1942 | Pennsylvania #4912 |

| 913 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 1/1942 | Pennsylvania #4913 |

| 914 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 6/1942 | Pennsylvania #4914 |

| 915 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 6/1942 | Pennsylvania #4916 |

| 916 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 6/1942 | Pennsylvania #4918 |

| 917 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 7/1942 | Pennsylvania #4919 |

| 918 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 7/1942 | Pennsylvania #4920 |

| 919 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 7/1942 | Pennsylvania #4924 |

| 920 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 8/1942 | Pennsylvania #4925 |

| 921 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 8/1942 | Pennsylvania #4926 |

| 922 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 9/1942 | Pennsylvania #4928 |

| 923 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 2/1943 | Pennsylvania #4929 |

| 924 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 2/1943 | Pennsylvania #4931 |

| 925 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 2/1943 | Pennsylvania #4932 |

| 926 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 3/1943 | Pennsylvania #4933 |

| 927 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 3/1943 | Pennsylvania #4934 |

| 928 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 4/1943 | Pennsylvania #4937 |

| 929 | Altoona (PRR) | GG-1 | 6/1943 | Pennsylvania #4938 |

| 901-953 | EMD | AEM-7 | 11/1979-12/1988 | (Purchased New) |

| 901-953 | EMD | AEM7-AC | 2000-2002 | (Rebuilt From AEM-7s) |

| 957-975 | GE | E60CH (HEP Generator) | 11/1975-6/1976 | (Purchased New) |

| 950-956 | GE | E60CP (Steam Generator) | 12/1974-10/1975 | (Purchased New) |

| 2000-2039 | Bombardier | Acela Express Power Car | 10/2000-6/2003 | (Purchased New) |

Other Roster Information

| Road Number | Builder | Model Type | Date Built | Notes/History |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 406 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 1/1988 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PHR #406 |

| 90200, 90208, 90213-15 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 3/1976-4/1976 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PH's #200, #208, #213-215 |

| 90218-90225, 90229 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 4/1976-5/1976 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PH's #218-225, #229 |

| 90230, 90250-90253 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 7/1977-10/1977 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PHR's #230, #250-253 |

| 90278, 90340 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 12/1977, 10/1980 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PH #278, #340 |

| 90368 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 6/1981 | Rebuilt From Amtrak F40PHR #368 |

| 90413 | EMD | NPCU (Non-Powered Control Unit) | 5/1978 | Rebuilt From GO Transit F40PHR #513 |