Canadian National Railway: Map, Logo, History, Photos

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

When the final pieces of Canadian National Railways (as originally spelled) came together in 1923, its network was even greater than rival Canadian Pacific's (CP). At more than 22,000 route miles CN operated from Nova Scotia to British Columbia.

It served virtually every corner of its home country although its creation was the result of nationalization in an effort to save several financially troubled railroads.

The entire process required several years, dating back to World War I, and brought together these systems under one flag.

- On March 21, 2021 rival Canadian Pacific announced it would be acquiring Kansas City Southern for $25 billion. The new railroad to emerge would be known as Canadian Pacific-Kansas City.

Canadian National subsequently made a counterproposal of $33.7 billion to acquire KCS. Ultimately, the Surface Transportation Board killed the CN proposal on August 31, 2021 by unanimously rejecting the CN-KCS Voting Trust. -

Throughout most of its corporate existence CN never enjoyed the financial success of CP. However, that has changed since the 1980's.

Today, as a privately owned corporation, Canadian National has shed its money-losing ways and today ranks fourth in annual revenue among the North American Class I's.

Photos

One of the Canadian National's handsome 4-8-4's, #6214, steams through Bayview, Ontario with commuter train #76 (Toronto - Hamilton) during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.

One of the Canadian National's handsome 4-8-4's, #6214, steams through Bayview, Ontario with commuter train #76 (Toronto - Hamilton) during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.History

This turnaround was achieved in many ways from abandoning hundreds of miles in redundant trackage to expanding its reach deep into the United States by purchasing Wisconsin Central and Illinois Central.

CN is one of seven remaining Class I's and its future appears quite bright. If the merger movement again reignites, expect Canadian National to be at the forefront of whatever realignment(s) take place.

The Canadian National Railway shares many similarities with the Consolidated Rail Corporation. Conrail was a quasi-public entity created by the United States Congress in the 1970's to save the ailing Northeastern rail industry. For most of its existence CN was also a publicly-owned corporation.

At A Glance

23,400 (1930) 15,292 (1997) 20,400 (2020) | |

If you were a railfan during, or before, the 1980s Canadian National was quite a treat to witness in action. Here was a railroad that offered everything from quaint branch line service, at far away places like bucolic Prince Edward Island, to electrified boxcabs serving Montreal commuters.

It also maintained an eclectic motive power fleet of first-generation diesels built by four of the five major manufacturers (General Electric, General Motors Diesel/Electro-Motive, Fairbanks-Morse/Canadian Locomotive Company, and Montreal Locomotive Works/American Locomotive). For purposes of this article only a brief synopsis of the CN will be presented.

If you would like a detailed history of the railroad there are several excellent titles out there, such as Mr. Murray's previously mentioned and the much more thorough "History Of The Canadian National Railways" by author G.R. Stevens.

Logo

Formation

To understand Canadian National's heritage a brief look at its predecessors is needed. The formation of CN officially began when the Canadian government took possession of the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR) following its completion in May of 1915.

Despite its name the NTR, at a total of 2,019 miles, was not a true transcontinental although it did help establish one by connecting with the Grand Trunk Pacific at Winnipeg, Manitoba and the Intercolonial Railway at Moncton, New Brunswick.

The addition of NTR added a third railroad to the government's portfolio as it also controlled the small Prince Edward Island Railway (PEI) and previously mentioned Intercolonial.

The PEI served its home island and was created following passage of the Prince Edward Island Railway Act on April 5, 1871.

The picturesque island, surrounded by the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Northumberland Strait, was made famous when author Lucy Maud Montgomery wrote "Anne Of Green Gables," in 1908.

It earned pop culture status with Canadian Broadcasting's 1985 release of the "Anne Of Green Gables" series starring Megan Follows as Anne Shirley.

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6024 has westbound train #80, a Toronto run, passing through Bayview, Ontario during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6024 has westbound train #80, a Toronto run, passing through Bayview, Ontario during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.The island also holds an important place in Canadian history. The Charlottetown Conference was held there from September 1st through 9th of 1864 where those representing colonies of British North America considered Confederation.

These efforts led to the Dominion of Canada's creation on July 1, 1867. Following passage of the railway act the PEI was envisioned to serve the entirety of the island (120 miles).

Its construction officially began on October 5, 1871 although, ironically, Prince Edward Island was not a part of Canada at that time.

The distrustful and independent islanders held out until finally joining on July 1, 1873. By then the railroad was largely complete although as Mr. Stevens' book notes it was poorly built.

When Canada assumed responsibility of the PEI this issue was remedied when the Intercolonial Railway oversaw its rebuilding, completed by 1875. At its peak the PEI connected Tignish with Elmira with branches to Georgetown, Murray Harbour, and Borden.

The later point provided car ferry service across the Northumberland Strait to Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick and an interchange with the Intercolonial.

The PEI primary handled agricultural products for the island's local communities and despite its superfluous nature (or, as Mr. Stevens put it, "...a stupid project from the start"), remnants of its network remained in operation until 1989.

A pair of Canadian National FPA4's, #6775 and #6752, board their train at Ottawa, Ontario on a gloomy November day in 1968. Author's collection.

A pair of Canadian National FPA4's, #6775 and #6752, board their train at Ottawa, Ontario on a gloomy November day in 1968. Author's collection.Expansion

The Intercolonial was the government's first involvement with railroads and was intertwined with Confederation. When the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia became part of Canada the new government agreed to connect the Maritimes by rail.

It was to be named the Intercolonial Railway and would link Truro, Nova Scotia with Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec where an interchange would be established with the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR).

It opened the same year the PEI was finished, 1875. The largest single system comprising Canadian National was one of similar name, the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) formed on January 13, 1899.

It was a joint effort of William Mackenzie and Donald Mann to break Canadian Pacific's transcontinental monopoly, which it had enjoyed since the early 1880's. Their endeavor began with the completion of the Winnipeg Great Northern Railway between Gladstone and Winnipegosis, Manitoba in late 1896.

With government assistance (loans and land grants) they pieced together a network across the western territories through new construction and acquisition. By 1906 the CNoR maintained a route from Port Arthur, Ontario to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan via Winnipeg.

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6214 steams west with train #117 at Komoka, Ontario bound for Detroit during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6214 steams west with train #117 at Komoka, Ontario bound for Detroit during the 1950's. Paul Meyer photo. Author's collection.Over the next few years MacKenzie and Mann continued pushing west, reaching Edmonton and then followed the Grand Trunk Pacific through Yellowhead Pass before turning southwesterly towards Vancouver. The line was completed when a final spike was driven at Basque, British Columbia.

By then the company had also established eastern connections linking Montreal with Toronto and extending service as far as the Maritimes. Despite these great achievements, a large central gap remained.

This changed in 1911 when the two businessmen began building a long, 1,050-mile route to join their eastern and western segments. It was finished in only a few years and the Canadian Northern officially opened as a transcontinental carrier on January 1, 1914.

With completion of the CNoR, boasting 11,000 route miles, MacKenzie and Mann finally had a railroad to compete against Canadian Pacific. Unfortunately, they had also overstretched their finances, which led to their largest creditor, the Canadian government, taking over the property on December 20, 1917.

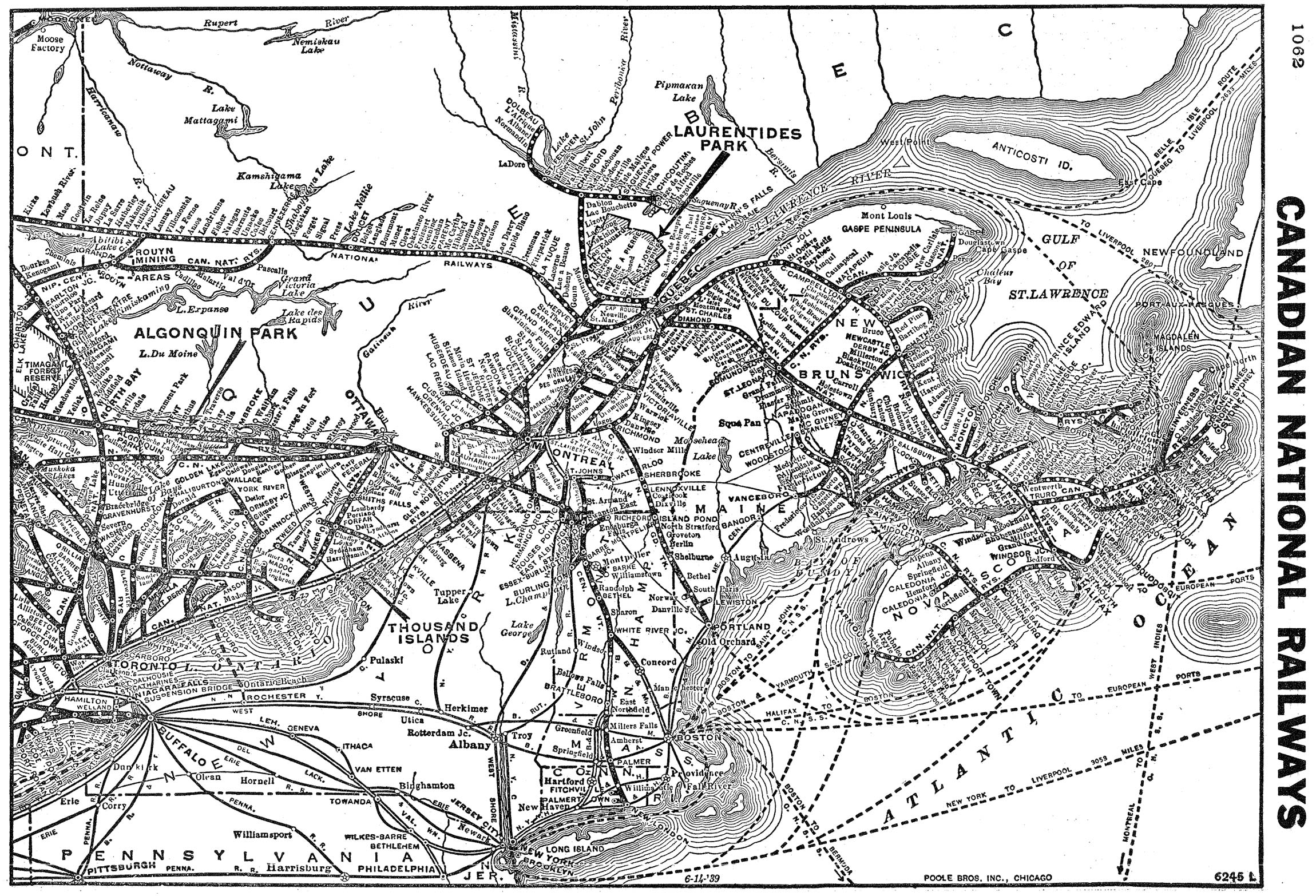

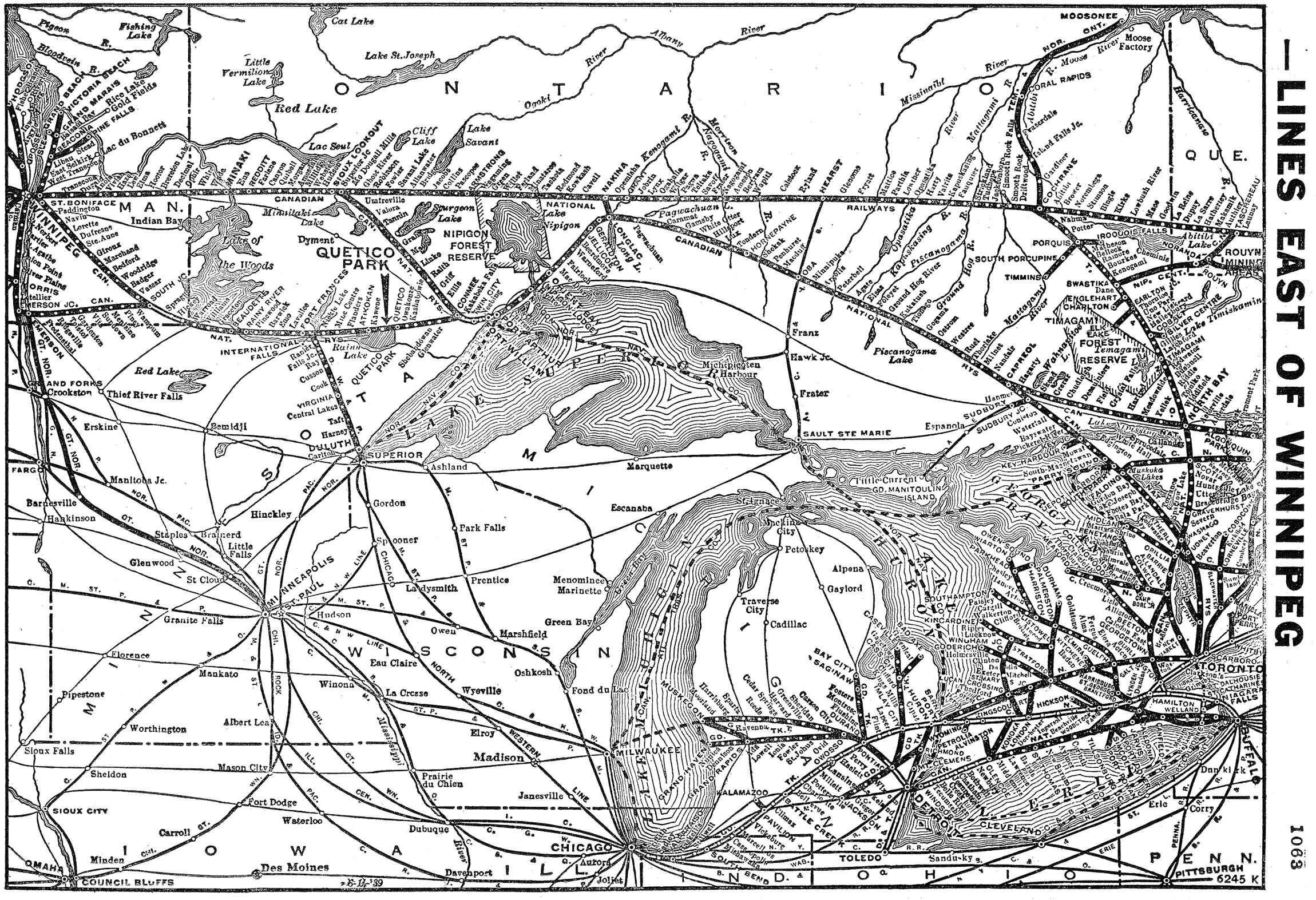

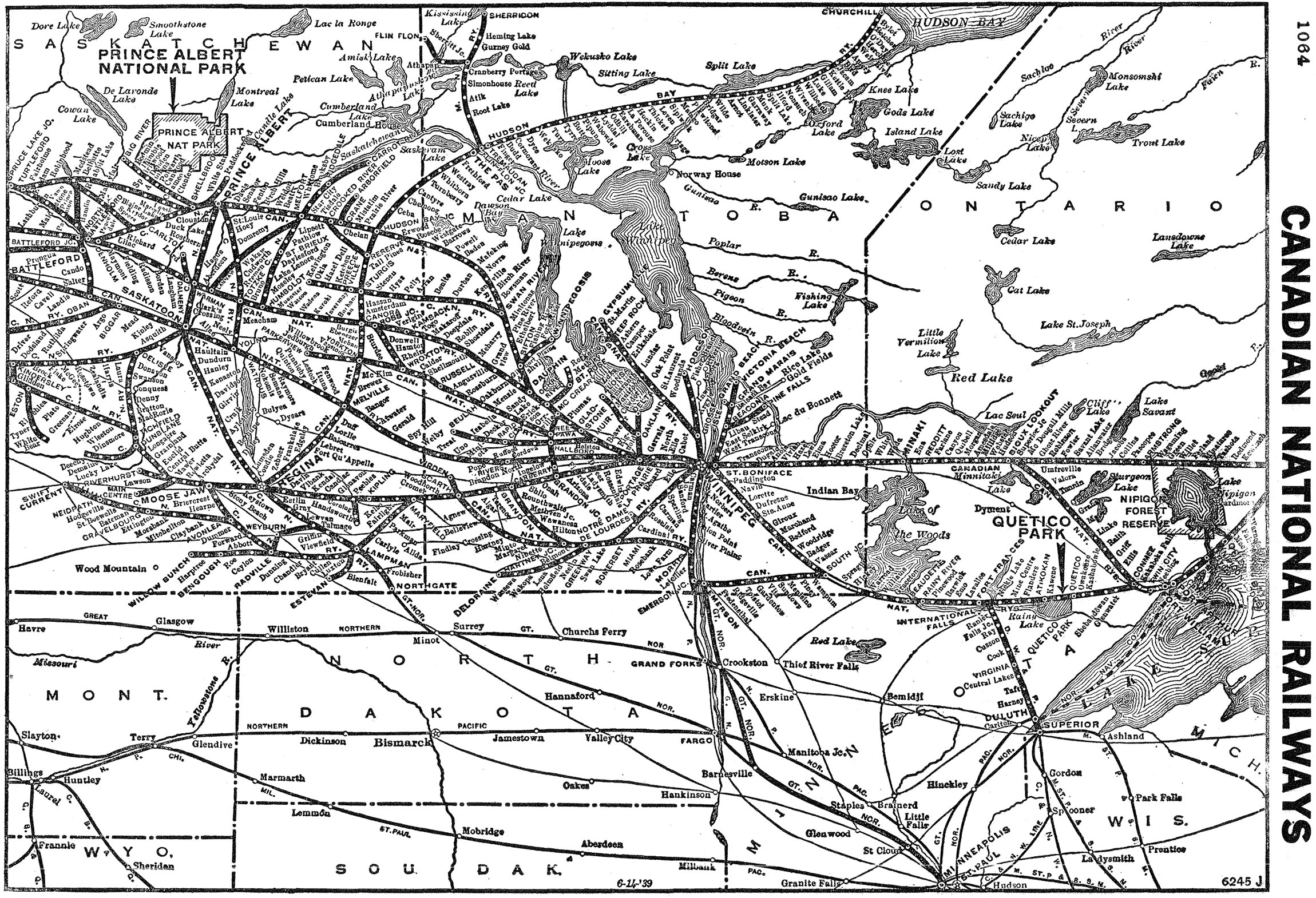

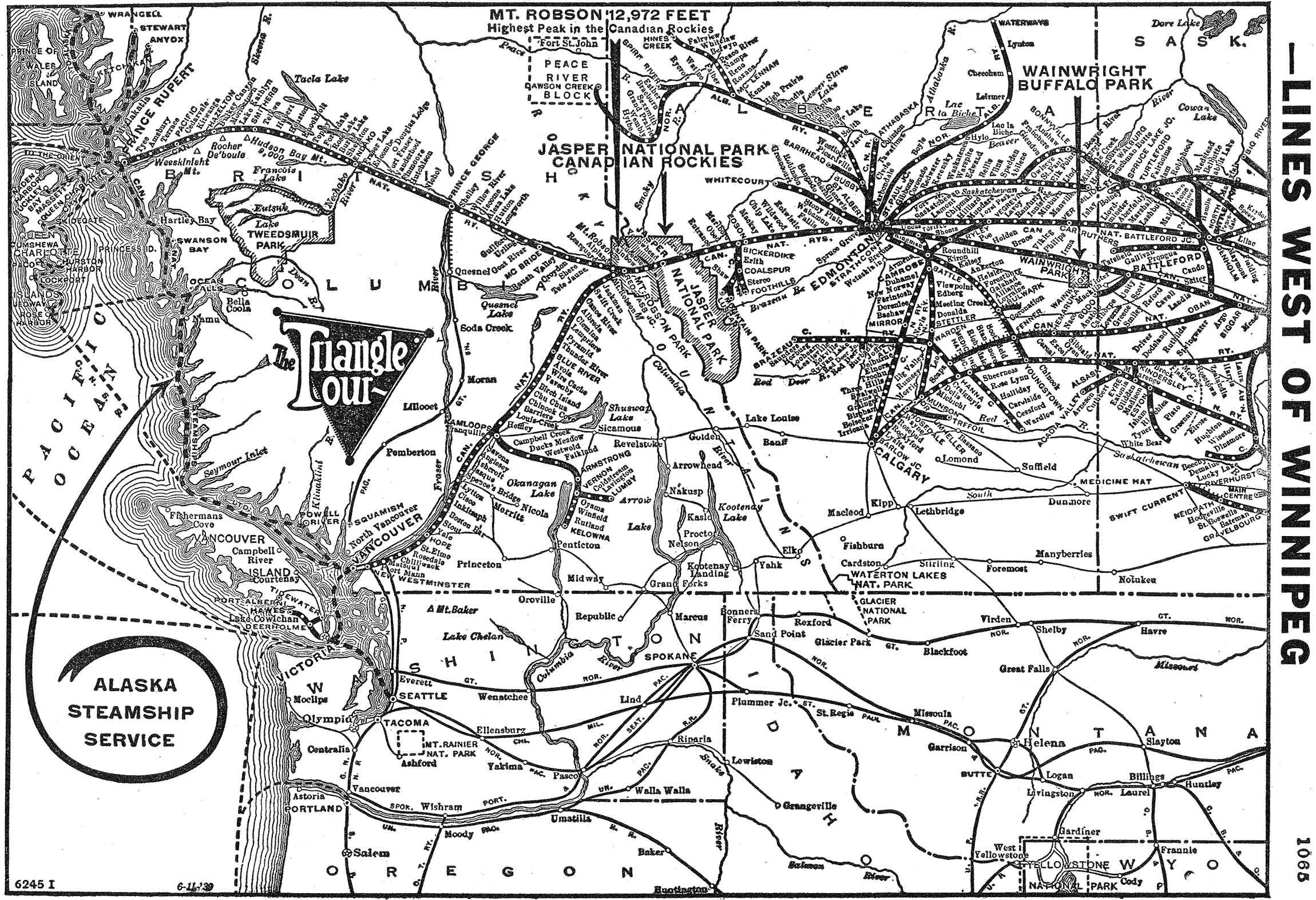

System Map (1939)

As part of this endeavor the government initiated a series of corporate restructurings; the Eastern Division of the National Transcontinental Railway (Moncton - Winnipeg), Intercolonial Railway, Prince Edward Island Railway, and eight short lines serving New Brunswick (totaling 4,205 miles) would be operated by the Canadian Northern and known as the "Canadian National Railways" with a combined total network of 13,610 miles.

The name at this time was used only loosely to describe the combined properties but that would soon change. CN's last notable component was the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) and its subsidiary, Grand Trunk Pacific (GTP).

The two provided another transcontinental option while subsidiaries offered connections in the U.S. at Duluth, Minnesota (Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific) and Chicago via Detroit (Grand Trunk Western).

A handsome Canadian National 4-6-2, #5302 (J-7c), departs Georgetown, Ontario during the 1950's. Author's collection.

A handsome Canadian National 4-6-2, #5302 (J-7c), departs Georgetown, Ontario during the 1950's. Author's collection.According to Don Hofsommer's book, "Grand Trunk Corporation: Canadian National Railways In The United States, 1971-1992" the GTR was incorporated on November 10, 1852 with intentions of connecting Portland, Maine with Detroit, Michigan via Montreal and Toronto. In just four years it had established a through route from Sarina, Ontario to Montreal via Toronto and Hamilton.

From this point it reached New England by acquiring full control of the bankrupt Central Vermont Railroad (1898) which ran south to New London, Connecticut.

In the west GTR had been working since the late 1850's to reach Chicago through a subsidiary later known as Grand Trunk Western. After outfoxing William Vanderbilt (son of the "Commodore") the railroad's promoters had stitched together a route into Chicago by early 1880.

Canadian National SW900m #7251 at work in Calgary, Alberta during early September of 1981. American-Rails.com collection.

Canadian National SW900m #7251 at work in Calgary, Alberta during early September of 1981. American-Rails.com collection.Despite a network that totaled more than 1,100 route miles, GTR's promoters sought their own extension to the Pacific coast in an effort to break up a status enjoyed by only Canadian Pacific and Canadian Northern. To do this the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was incorporated on October 24, 1903.

The entire project was led by Charles Hays, an American who held experience in operating American railroads. Alas, he was tragically killed when the Titanic sank on April 14, 1912. However, before that fateful voyage Hays oversaw GTP's completion and a third transcontinental serving Canada.

While the previously mentioned National Transcontinental focused on the segment east of Moncton, GTP constructed the Western Division (1,804 miles) to reach the Pacific. The project officially began on August 29, 1905 with the final alignment crossing Yellowhead Pass at the border with British Columbia/Alberta.

Curiously, it did not turn south towards Vancouver like CP and CNoR. Instead, it pushed west to a desolate point on the coast known as Prince Rupert, situated not far from the Alaska border.

The line was completed on April 9, 1914 and a deep water port was eventually established there. However, it never enjoyed the substantial business of Vancouver and largely played an insignificant role on west coast trade.

A trio of Canadian National GP38-2's, led by #5547, have an eastbound near Beachville, Ontario on August 27, 1977. J. Bryce Lee photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A trio of Canadian National GP38-2's, led by #5547, have an eastbound near Beachville, Ontario on August 27, 1977. J. Bryce Lee photo. American-Rails.com collection.Alas, GTR suffered the CNoR's fate; having overstretched is financial resources its primary creditor, the Canadian government, took control on May 21, 1920. It was eventually folded into the new Canadian National Railway (created on June 6, 1919) during January of 1923.

From that point forward the 22,681-mile system was collectively known as Canadian National Railways (the "s" was later dropped).

It was certainly an impressive railroad in terms of size but CN was constantly plagued with a high operating ratio (expenses as a percentage of revenue), which sometimes topped 100%.

Canadian National FP9 #6526 leads train #48 at Deep Cut Junction in Ottawa in September, 1963. Rick Burn photo.

Canadian National FP9 #6526 leads train #48 at Deep Cut Junction in Ottawa in September, 1963. Rick Burn photo.As a result, it consistently posted deficits. Only during the traffic surge of World War II did CN boast a ratio in the low 70's (73%), a number it would not enjoy again until the 1990's.

In spite of its problems the railroad was important to the Canadian economy by moving millions in freight tonnage annually, offering high quality passenger service, and hosting necessary suburban operations within Montreal.

- This electrified service was the result of a tunneling project, which began in 1913 and completed in 1918, to reach the city's downtown area. Running via Mount Royal it was 3.2 miles in length and utilized six boxcab electrics manufactured by General Electric. -

After World War II CN began replacing its steam fleet with new diesels; interestingly, while it had experimented with the technology since 1929 (1,330-horsepower boxcabs #9000 and #9001 built by the Canadian Locomotive Company in Kingston, Ontario, designed by chief of motive power C.E. Brooks) the railroad was slow to fully dieselize.

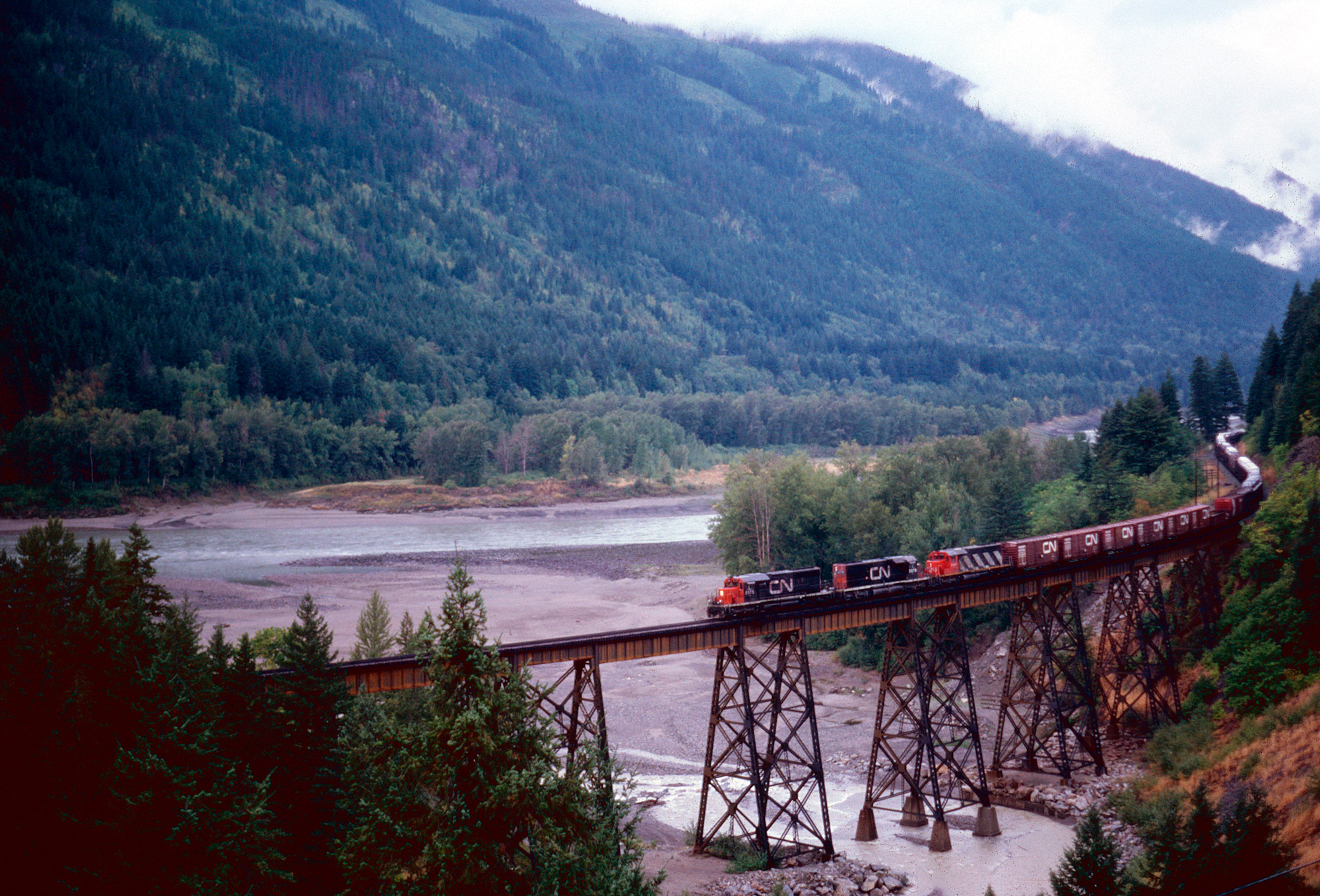

A trio of Canadian National SD40-2's, led by #5175, head west through the Fraser River Canyon in British Columbia; August, 1981. American-Rails.com collection.

A trio of Canadian National SD40-2's, led by #5175, head west through the Fraser River Canyon in British Columbia; August, 1981. American-Rails.com collection.It purchased its first road service models in 1948 when F3's arrived from Electro-Motive that year. The railroad also acquired a batch of 650 horsepower units from Whitcomb and the Canadian Locomotive Company to operate on Prince Edward Island.

As new diesels continued arriving they were assigned on a territory-by-territory basis until steam had been retired completely by April of 1960.

The new motive power wore an attractive livery of Pullman green with yellow and black accents in addition to a Maple Leaf logo within which was displayed "Canadian National Railways."

If you were a railroad enthusiast at this time CN's first-generation motive power offered a fascinating look at a variant of models from FP9's and Rs18's to the unique GMD-1 and odd RSC24 (a stubby road-switcher rebuilt by Montreal Locomotive Works from FPA-2's).

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6218 (Class U-2-g) leads a fan trip over the Grand Trunk Western at Stillwell, Indiana in November 20, 1966. Rick Burn photo.

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6218 (Class U-2-g) leads a fan trip over the Grand Trunk Western at Stillwell, Indiana in November 20, 1966. Rick Burn photo.The railroad would later pioneer the use of ditch lights in the 1950's along with the now standard “safety cab."

Into the 1960's other initiatives aimed at improving operations included installation of centralized traffic control (CTC) and a computerized car/train tracking system known as "Traffic Reporting And Control System" (TRACS).

With shifts in traffic patterns and customer needs, CN became adept at producing specialized equipment, not hesitating to test/build new car types when needed. It was quick to jump into the trailer-on-flatcar movement (TOFC) in the postwar years and later adopted container-on-flatcar (COFC) service still in widespread use today.

Timetables (1952)

The road to Canadian National's transformation into a perennially successful railroad began during the 1970's. In 1977 VIA Rail was established as a CN subsidiary to handle countrywide passenger services, including those offered by Canadian Pacific.

It was essentially Canada's version of America's Amtrak formed a few years earlier in 1971.

In 1978, VIA Rail became a separate corporate entity (a "Crown" corporation), and was completely free from CN control thus removing the railroad's burden of maintaining passenger services entirely.

There were two other important initiatives undertaken at this time; in 1967 the government had passed the National Transportation Act.

This legislation was somewhat similar to the United States' Staggers Act of 1980 which greatly deregulated the industry, enabling Canadian roads to more freely abandon unprofitable branch lines.

In 1971 CN created the Grand Trunk Corporation (GTC) which brought together its American properties under one name (Central Vermont; Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific; Grand Trunk Western).

The effort was designed to improve and streamline operations, particularly at Grand Trunk Western. Like CN, GTW was historically a money-losing venture even though it operated a key route between Detroit and Chicago.

The creation of GTC changed all of that and by the late 1970's GTW had posted its first stand-alone net profit in several decades.

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6218 (U-2-g) departs Belleville, Ontario with a special excursion on May 3, 1971. Carl Sturner photo. Author's collection.

Canadian National 4-8-4 #6218 (U-2-g) departs Belleville, Ontario with a special excursion on May 3, 1971. Carl Sturner photo. Author's collection.As one of Canada's two largest railroads, Canadian National fielded an expansive passenger fleet. Its best remembered trains were the Maple Leaf, International Limited, Montrealer, Super Continental, Continental Limited, Washingtonian and Ambassador but there were many others.

Interestingly, while CN employed streamlining it found the styling was most advantageous on steam locomotives where it created greater benefits for improved crew visibility through the use of smoke deflectors.

In later years CN adopted second-hand streamlined equipment from U.S. roads, most famous of which were Milwaukee Road’s "Super Domes" and "Skytops" no longer needed after the railroad gave up its transcontinental Olympian Hiawatha in 1961.

Passenger Trains

Ambassador/New Englander: (Boston - Montreal)

Caribou: (St. John's - Port aux Basques)

Continental Limited: (Montreal/Toronto - Vancouver)

The Gull: (Boston - Halifax, Nova Scotia)

Canadian National CPA16-5 #6705 ("C-Liner") leads train #55, the westbound "Bonaventure," at Brockville, Ontario during August of 1966. Bill Linley photo.

Canadian National CPA16-5 #6705 ("C-Liner") leads train #55, the westbound "Bonaventure," at Brockville, Ontario during August of 1966. Bill Linley photo.Inter-City Limited: (Montreal - Toronto - Detroit/Chicago)

International Limited: (Montreal - Toronto - Chicago)

Maple Leaf: (Toronto - Philadelphia/New York City)

Montrealer/Washingtonian: (Washington - New York - Montreal)

Northland: (Toronto - North Bay/Timmins/Kapuskasing, Ontario)

Ocean Limited: (Montreal - Halifax)

Scotian: (Montreal - Halifax)

Super Continental: (Montreal/Toronto - Vancouver)

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6060 hosts a fan trip near La Malbaie, Quebec on September 26, 1976. Ken Wadden photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6060 hosts a fan trip near La Malbaie, Quebec on September 26, 1976. Ken Wadden photo. American-Rails.com collection.Today

Canadian National earned its first profit in some twenty years for fiscal year 1976 and slowly worked to improve its operating ratio as the government forgave millions in obligated debt. The 1980's and 1990's were spent shedding redundant secondary trackage.

By the 1990's the railroad was generating enough positive cash flow to operate independently. It continued reducing its network, which by 1997 had dropped to just 15,292 route miles.

That same year its operating ratio dipped below 80%. In an interesting twist, it grew a year later when it acquired the storied Illinois Central, taking formal control on July 1, 1999.

While the IC was also greatly slimmed down it offered access to America's Gulf Coast at New Orleans and interchanged with Union Pacific at Council Bluffs/Omaha. On November 17, 1995 Canadian National was officially privatized when its shares went public.

Ironically, U.S. investors, with more confidence than their northern neighbors in the railroad's future, wound up as the largest stockholders. More takeovers continued into the 2000's when regional Wisconsin Central was purchased in 2001.

A few years later on January 31, 2009 CN picked up the historic Elgin, Joliet & Eastern to bypass congested Chicago.

Today, Canadian National is one of the top North American Class I's earning healthy profits in a revitalized industry. Whether its name will remain in the next round of mega-mergers is unknown but the railroad will almost certainly be a major player when they do occur.

Recent Articles

-

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail. -

Duffy's Cut: A Forgotten Railroad Tragedy

Jan 29, 26 11:05 AM

Duffy's Cut is an unfortunate incident which occurred during the early railroad industry when 57 Irish immigrants died of cholera during the second cholera pandemic. -

Wisconsin Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:47 PM

This article delves deep into the passenger and commuter train services available throughout Wisconsin, exploring their history, current state, and future potential. -

Connecticut Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:30 PM

Connecticut's passenger and commuter train network offers an array of options for both local residents and visitors alike. Learn more about these services here. -

South Dakota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:29 PM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:23 PM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Florida ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:18 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards. -

Texas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:08 AM

This article invites you on a metaphorical journey through some of these unique wine tasting train experiences in Texas. -

New York ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:05 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:04 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

Indiana ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:59 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:57 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Minnesota Valentine's Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:51 AM

One of the most charming examples of MTM’s family-friendly programming is “The Love Train,” a Valentine’s-themed day that blends short train rides with crafts, treats, and playful activities inside th… -

Georgia Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 10:03 PM

Georgia offers a variety of train services, from historic scenic routes to modern commuter trains serving the Atlanta metropolitan area. -

Illinois Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 02:49 PM

Learn more about Illinois's current passenger rail options, ranging from Amtrak to the Twin Cities' light rail service. -

Pennsylvania Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 02:40 PM

Here is a detailed, statewide look at the passenger rail services you can use today—focusing on intercity (long-distance and regional) options, primarily operated by Amtrak—plus the major commuter and…