Montrealer/Washingtonian (Train): Timetable, Route, Consist

Last revised: February 27, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Montrealer/Washingtonian was the same route named for the two cities the train served; Washington, D.C. and Montreal, Quebec.

This once popular corridor required five different railroads to complete the journey which included - from north to south - the Canadian National, Central Vermont, Boston & Maine, New Haven, and Pennsylvania.

The PRR was an important component for any railroad interested in through service to the Northeast's major cities as the railroad's electrified Northeast Corridor provided efficient and high-speed service to Baltimore, Washington, Philadelphia, and New York.

Inaugurated a few years before the Great Depression the Montrealer/Washingtonian would close out long-distance international rail travel in New England when both were discontinued in the mid-1960s.

History

We, as a species, often think of ourselves as constantly progressing forward from both a societal and technological standpoint. In many ways this is certainly true while in other respects it it is not. Take, for example, our national infrastructure.

Highways and interstates now crisscross the nation - and continue to expand even as we speak - providing immense freedoms via the automobile. In addition, airlines can travel from coast-to-coast in only a few hours.

However, neither mode is truly stress free nor provides the level of relaxation afforded by rail. Yes, we have Amtrak for intercity service but this carrier offers only a fleeting glimpse of the so-called "Golden Age."

There is a reason trains are historically romanticized through stories, books, and movies; it really was a first-class, civilized way to travel.

Once upon a time on-board accommodations included things like lounge cars, Pullman sleepers, and five-star, gourmet meals freshly prepared en route. One such route offering this level of service was the Montrealer/Washingtonian.

In years past these trains not only hosted general passengers but also business clientele and U.S./Canadian diplomats traveling to their respective nation's capitals (Ottawa could be reached via a connection from the CN at Montreal).

According to Kevin Holland's book, "Passenger Trains Of Northern New England, In The Streamline Era") the train's overnight schedule enabled an early morning arrival at each destination city.

Inauguration

The Montrealer/Washingtonian was inaugurated on June 15, 1924 and originally steam-powered, carrying an all-heavyweight consist. The northbound run was known as the Montrealer while its southbound counterpart was referred to as the Washingtonian.

The following railroads handled the train; the Pennsy between Washington and New York, the New Haven from New York to Springfield (Massachusetts), Boston & Maine between Springfield and White River Junction (Vermont), Central Vermont from there to St. Albans (Vermont), and finally the Canadian National between Cantic, Quebec and Montreal.

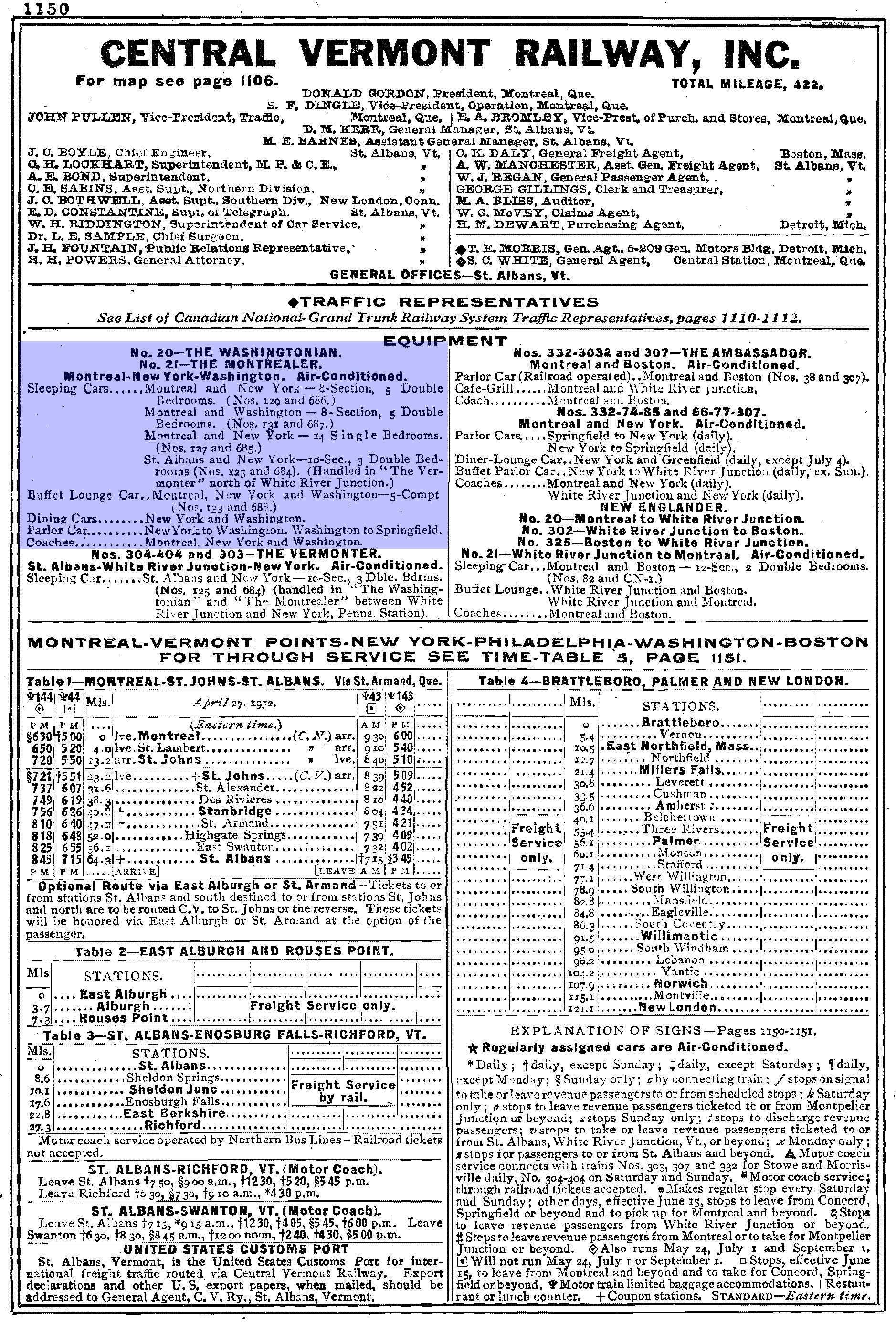

Timetable and Consist (1952)

PRR

Central Vermont

Boston & Maine

New Haven

Accommodations

The service received its first significant upgrades when, as Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon note in their book, "Pennsylvania Railroad," the PRR completed the electrification of its New York-Washington main line.

The Philadelphia-New York segment was completed in 1933 while the remaining section to Washington, D.C. opened on February 10, 1935.

A normal consist for the Montrealer/Washingtonian (although often subject to slight changes) included:

- Buffet-lounge (New York-Montreal)

- Three sleepers (6-6-4 Washington-Montreal, 6-6-4 New York-Montreal, and a 6-6-4 New York White River Junction)

- Parlor (Washington-Montreal)

- Diner (Washington-Montreal)

- Two reclining seat coaches

- Parlor-observation (New York-Washington)

While the trains were never complete streamliners they did carry lightweight sleepers after World War II, including from CN's own Green series leased to Pullman.

Timetable (August 8, 1960)

| Read Down Time/Leave (Train #152/Pennsylvania) | Milepost | Location | Read Up Time/Arrive (Train #115/Pennsylvania) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4:00 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 1:15 PM (Ar) | |

| 4:40 PM | 40.1 | 12:35 PM | |

| 5:39 PM | 108.5 | 11:33 AM | |

| 6:06 PM | 11:05 AM | ||

| 6:14 PM | 140.7 | 10:56 AM | |

| 168.5 | 10:29 AM | ||

| 7:20 PM | 216.6 | 9:45 AM | |

| 7:35 PM (Ar) | 226.6 | 9:30 AM (Dp) | |

| Time/Leave (Train #168/New Haven) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #169/New Haven) |

| 8:35 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 8:00 AM (Ar) | |

| 9:23 PM | 36.0 | ||

| 9:51 PM | 58.5 | 6:51 AM | |

| 10:10 PM (Ar) | 75.0 | 6:30 AM (Dp) | |

| 10:25 PM (Dp) | 75.0 | 6:22 AM (Ar) | |

| 10:54 PM | 93.5 | 5:58 AM | |

| 11:07 PM | 101.0 | ||

| 11:20 PM (Ar) | 111.5 | 5:35 AM (Dp) | |

| 11:35 PM (Dp) | 111.5 | 5:31 AM (Ar) | |

| 12:15 AM (Ar) | 137.0 | 5:00 AM (Dp) | |

| Time/Leave (Train #21/Boston & Maine) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #20/Boston & Maine) |

| 12:40 AM (Dp) | 137.0 | 4:20 AM (Ar) | |

| 1:29 AM | 173.1 | 3:10 AM | |

| 2:12 AM | 197.3 | ||

| 2:42 AM | 221.0 | 2:12 AM | |

| 3:45 AM (Ar) | 260.2 | 1:20 AM (Dp) | |

| Time/Leave (Central Vermont) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Central Vermont) |

| 4:00 AM (Dp) | 260.2 | 1:05 AM (Ar) | |

| 5:09 AM | 313.2 | ||

| 5:20 AM (Ar) | 321.8 | 11:47 PM (Dp) | |

| 5:25 AM (Dp) | 321.8 | 11:44 PM (Ar) | |

| 5:38 AM | 331.4 | 11:32 PM | |

| 6:04 AM (Ar) | 353.6 | 11:04 PM (Dp) | |

| 6:10 AM (Dp) | 353.6 | 11:01 PM (Ar) | |

| 6:42 AM (Ar) | 377.4 | 10:31 PM (Dp) | |

| 6:51 AM (Dp) | 377.4 | 10:28 PM (Ar) | |

| Time/Leave (Canadian National) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Canadian National) |

| 402.8 | 8:44 PM (Dp) | ||

| 6:44 AM (Dp) | 402.8 | 8:43 PM (Ar) | |

| 7:08 AM | 419.5 | 8:20 PM | |

| 7:34 AM | 438.7 | 7:54 PM | |

| 7:55 AM (Ar) | 442.7 | 7:40 PM (Dp) |

Interestingly, through the 1950s Pullman equipment remained primarily heavyweight in nature while the streamlined cars often came from the four participating roads' own pool.

Considering how ridership was rapidly declining by this time, particularly in the Northeast and New England, it's somewhat amazing that sleeper/Pullman service survived as long as it did. As Mr. Holland notes the railroads were quite aware of the declining patronage and growing financial losses.

By the 1960s the B&M, CN, and New Haven began bickering over which types of sleepers should be assigned to the train's consist when, in reality, the main issue centered around participation in the Pullman deficit.

Final Years

Because of New England's susceptibility to the automobile, rail service here faded particularly quickly. As Mr. Holland points out by 1960 only the Montrealer/Washingtonian and Ambassador were still in serving in their long distance roles. In addition, they were the only trains on the B&M still carrying conventional, non-RDC (Rail Diesel Car) equipment.

Perhaps, then, it was fitting that both disappeared together making their final runs during September 3rd and 4th of 1966 despite court battles to keep all three in service; the last northbound Montrealer operated on the 3rd while the final southbound Washingtonian, carrying a five-car consist, entered history a day later on the 4th.

Sources

- Holland, Kevin J. Passenger Trains Of Northern New England, In The Streamline Era. Lynchburg: TLC Publishing, 2004.

- Lynch, Peter E. New Haven Passenger Trains. St. Paul: MBI Publishing Company, 2005.

- Murray, Tom. Canadian National Railway. St. Paul: MBI Publishing Company, 2004.

- Schafer, Mike and Solomon, Brian. Pennsylvania Railroad. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1997.

- Stevens, G.R. History Of The Canadian National Railways. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1973.

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:54 PM

Through a unique blend of interactive entertainment and historical reverence, Wisconsin offers a captivating glimpse into the past with its Wild West train rides. -

Georgia's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:44 PM

Nestled within its lush hills and historic towns, the Peach State offers unforgettable train rides that channel the spirit of the Wild West. -

North Carolina's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:36 PM

North Carolina, a state known for its diverse landscapes ranging from serene beaches to majestic mountains, offers a unique blend of history and adventure through its Wild West train rides. -

South Carolina's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:16 PM

There is only location in the Palmetto State offering a true dinner train experience can be found at the South Carolina Railroad Museum. Learn more here. -

Rhode Island's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:08 PM

Despite its small size, Rhode Island is home to one popular dinner train experience where guests can enjoy the breathtaking views of Aquidneck Island. -

New York Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:56 PM

Tea train rides provide not only a picturesque journey through some of New York's most scenic landscapes but also present travelers with a delightful opportunity to indulge in an assortment of teas. -

California Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:37 PM

In California you can enjoy a quiet tea train experience aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train, which offers an afternoon tea service. -

Tennessee Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:19 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Ohio "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:34 AM

For those enamored with tales of the Old West, Ohio's railroad experiences offer a unique blend of history, adventure, and natural beauty. -

New York "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:23 AM

Join us as we explore wild west train rides in New York, bringing history to life and offering a memorable escape to another era. -

New Mexico Murder Mystery Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:12 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails -

New York Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:09 AM

While CMRR runs several seasonal excursions, one of the most family-friendly (and, frankly, joyfully simple) offerings is its Ice Cream Express. -

Michigan Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:02 AM

If you’re looking for a pure slice of autumn in West Michigan, the Coopersville & Marne Railway (C&M) has a themed excursion that fits the season perfectly: the Oktoberfest Express Train. -

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 10:07 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour…