Great Railroad Strike Of 1877

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was an uprising launched in response to pay cuts enacted by the country's largest railroads following the financial Panic of 1873.

The proverbial straw that broke the camel's back was a 10% wage reduction, which had followed several others over the previous four years.

Unfortunately, in a time when blue collar employees enjoyed virtually no job protections, these measures made it all but impossible for workers to fight back.

Definition

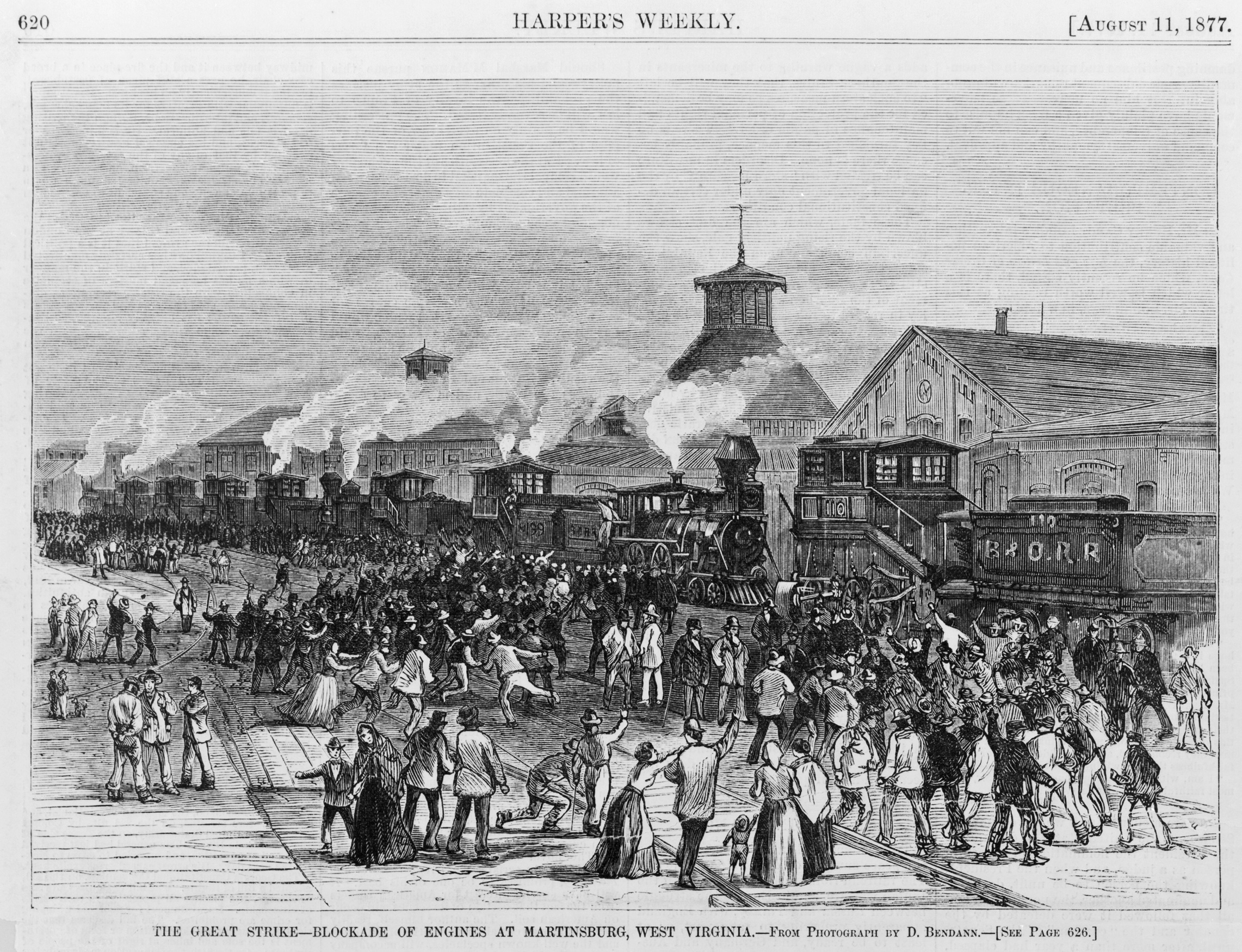

Along the Baltimore & Ohio this reached a boiling point; believing they had no other recourse, workers at the railroad's shops and major division point of Martinsburg, West Virginia walked off the job on July 26, 1877. Due to its strategic location the move paralyzed B&O's operations.

As freight trains sat idle employees of other railroads, realizing the strike's effectiveness, joined the cause; even workers outside the industry, who had also been oppressed, walked off the job.

What Happened

While the movement lasted less than a month, and ultimately ended in failure, it sparked a revolution which brought about today's modern unions. It also had a secondary effect of bringing about federal oversight and laws to protect employees.

Life as a railroader in the 1870's was not an easy occupation filled with many dangers, few safety measures, and long hours. To make matters worse the financial Panic of 1873 crippled the nation and put many Americans out of work.

According to the book, "The Great Strikes Of 1877" by David O. Stowell, there were around 30 national and international trade unions operating within the United States just prior to the panic. At the time, the country was enjoying a great economic boom in the peacetime following the Civil War.

This included the railroad industry which was rapidly expanding in the decade after the conflict by laying down more than 40,000 miles between 1870 and 1880 according to John Stover's book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads."

In addition, roughly 34,000 miles were spiked down in just an 8-year period, 1865 - 1873. By contrast, only 6,000 miles were added in the four years after the economic downturn (1873-1877).

As railroads blossomed into America's second-largest employer (trailing only the agricultural/farming industry), much of the new trackage was built on speculation thanks to cash availability and the strong economy.

Unfortunately, this led to a house-of-cards scenario; coupled with Congress's passage of the Coinage Act (American currency would no longer be backed with silver), the stage was set for the events of 1873.

That year, the Northern Pacific Railway, attempting to complete the Pacific Northwest's first transcontinental railroad, was having considerable difficulty producing enough revenue to continue selling bonds.

At A Glance

Interstate Commerce Commission (February 4, 1887) Safety Improvements National Industrial Regulations Railroad Unions Formed |

These were marketed by Jay Cooke's banking firm, Jay Cooke & Company, throughout the U.S. and abroad. With the railroad struggling, the bank essentially wrote blank checks to further bond sales.

When this failed a run on the bank commenced and Cooke's firm, along with the railroad, entered bankruptcy on September 18, 1873. The event sparked one of America's worse depressions, a crisis which would endure for six years.

As a result of the economic calamity, Mr. Stowell's book notes that the number of organized unions dropped had from 30 to 9 by the time the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 began. In response to plummeting revenue, railroads were quick to implement wage cuts although many continued to pay dividends.

As Philip S. Foner notes in his book, "The Great Labor Uprising Of 1877," railroads reduced workers' salary by an average of 21%-37% although food prices had declined only 5%. The Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) was particularly egregious by slicing pay up to 50%.

Cause And Effect

Although events along the B&O initiated the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, in essence it began slowly, taking on a life of its own over time.

In addition, a series of events which had occurred a few years prior could be rightfully argued as its genesis; between November, 1873 and July, 1874 workers struck along eighteen different railroads in response to a series of initial wage cuts.

In every case, the walkouts were brief, lasting for only a week or two and never drawing the nation's attention. For railroads, the usual tactic to quell such unrest was simply firing and blacklisting any employee(s) involved. This usually worked although the 1873/74 incidents proved a foreshadowing of things to come.

The country's very first strike is believed to have occurred between June 20th and 30th of 1831 along the B&O. What followed was a series of related events that never gained any effective traction in breaking the draconian rule large corporations held over their workers.

Empathy was sometimes expressed in local media outlets but no national change ever came about since big business controlled the political arena. As a result, organized labor had little recourse in obtaining better pay, consistent hours, and job protections.

During the 1870's there were only four significant trade unions within the railroad industry; the Machinists' and Blacksmiths' International Union (MBIU), Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF), Brotherhood of Railway Conductors (BRC), and Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE).

Only the latter, with some 10,000 members strong, held any significance but its powers were minor due to a lack of federal and state support.

In addition, the BLE's Grand Chief Engineer at the time, Charles Wilson, balked at striking. He also refused to stand with workers outside the union in a unified effort to bring about change.

Nevertheless, many, whether part of organized labor or not, felt their condition bleak by 1877. This was particularly true along the Baltimore & Ohio where workers suffered another 10% wage cut that summer.

Not only had many railroads implemented deep cuts but also provided employees with virtually no expense coverages.

For instance, they were often required to stay in opulent hotels (railroad-owned) when away from home, pay for return tickets, and, of course, cover all other expenses (such as meals) while away.

Along the B&O the latest cuts went into effect on Monday, July 16, 1877.

In response, the fireman of locomotive #32, leading a train about to depart Camden Junction, Maryland (Baltimore), walked off the job. His move triggered several fellow firemen to do the same.

These spontaneous acts forced the B&O's hand which called on Baltimore's mayor, Ferdinand C. Latrope, to mobilize the police. The show of force worked and would be used time and again to stop such uprisings along other railroads.

Just as the B&O thought the issue was over it reignited the following day when 38 engineers joined the cause, backed by 140 workers of Baltimore's Boxmakers' And Sawyers' Union and 800 tin can makers. The latter did so for the same reason as the railroaders, wage reductions.

Interestingly, despite being labeled "rioters" the strikers never once stopped passenger/mail trains (a calculated decision, no doubt, which would have halted the movement of federal property [mail] and brought further problems to their cause). Instead, they focused only on holding freight movements, the primary profit component of any railroad.

Location

From this point tensions escalated quickly. In Martinsburg, West Virginia, situated roughly 90 miles from Baltimore, B&O workers (most belonging to the local Trainmen's Union) went on strike during the evening of July 16th, declaring freight trains would not move until the railroad restored the 10% wage cut.

The railroaders were only fighting for better pay, enough to feed and house their families. Unfortunately, they were painted as rioters, vagrants, and disrupters of peace. In some newspapers they were even pegged as shadow communists, a ridiculous claim which held no merit.

But with the political cards in their favor, the railroads enjoyed all the power. The B&O successfully convinced West Virginia's governor, Henry M. Mathews, to call up the local militia to break the strike. Under guard, a scab engineer (i.e., strikebreaker), began leading a freight train out of the yard on July 17th in an effort to reestablish some semblance of service.

Determined to stop this, striker William P. Vandergriff wound up in a skirmish with militiamen. After an exchange of gunfire he was hit three times and later died. Still unable to resume full service, the B&O called for federal support but was initially rebuffed.

By this time the strike was garnering national attention as more and more papers picked up the story, particularly following the Vandergriff incident.

By July 18th, with no end in sight, Governor Matthews' call for U.S. troops was answered by President Rutherford Birchard Hayes. On the morning of July 19th Army regulars arrived in Martinsburg but were surprised to find almost nothing out of place.

There was no property destruction or other significant disturbances ongoing. The following day the B&O brought in fresh replacements and oversaw the arrest of many strikers which, backed by the army, essentially ended the unrest in Martinsburg.

The railroad's problems, though, were far from over as several other strikes had broken out across its then-2,700 mile network. Most notable was back in Baltimore where the strikes had continued but remained largely quiet and uneventful.

That changed on the night of July 20th when the B&O pressed the matter by breaking up the ongoing protest, calling for the arrest or firing of anyone involved. The railroad was backed by 120 militia (later reduced to 59 when several lost interest); with this show of force an effort was made to get the trains moving.

Perhaps not expecting such strong local support, the remaining soldiers were pelted with stones and jeers. They responded by opening fire. What was later dubbed the "Second Battle Of Bunker Hill," 11 people died and 40 others wounded.

The now enraged crowd, which swelled to 15,000, forced the militiamen to barricade themselves inside Camden Station's train sheds.

The rioters and townsfolk attempted to burn down the structure but were unsuccessful. Over the following weekend the incident subsided, aided by 1,200-2,000 federal troops to restore peace.

Pennsylvania Railroad

This was the last notable incident along the B&O, although strikes soon flared up elsewhere. The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) of 1877, like the Baltimore & Ohio, was generally despised due to its poor working conditions and even poorer pay.

On July 16th, the day the strikes began on the B&O, the PRR informed Western Division employees that as of July 19th all eastbound trains to Altoona would be double-headed due to the ongoing depression.

It further stipulated that fewer crewmen would be needed, all the while refusing to install safety devices like the knuckle coupler and automatic air bake.

By and large the PRR had received nothing more than complaints when carrying out similar actions elsewhere across its system. In this case, however, the timing couldn't have been worse.

With the workers aware of the Martinsburg ordeal, and already upset over their own wage cuts, two brakemen and one flagman of an eastbound freight train departing Pittsburgh on July 19th at 8:40 AM refused to go.

This move sparked a chain reaction which shutdown PRR's Pittsburgh operations, a major terminal and division point. With support of the local populace workers attempted arbitration, which proved unsuccessful.

Instead, PRR officials opted to use force, convincing Pennsylvania's Adjunct General James W. Latta (Governor John F. Hartranft was away in Wyoming Territory at the time) to call up the state's Sixth Division in Pittsburgh.

Fearing the Sixth would be loyal to the strikers, it was quickly replaced by Philadelphia's First Division, soldiers who had no direct connection with the men.

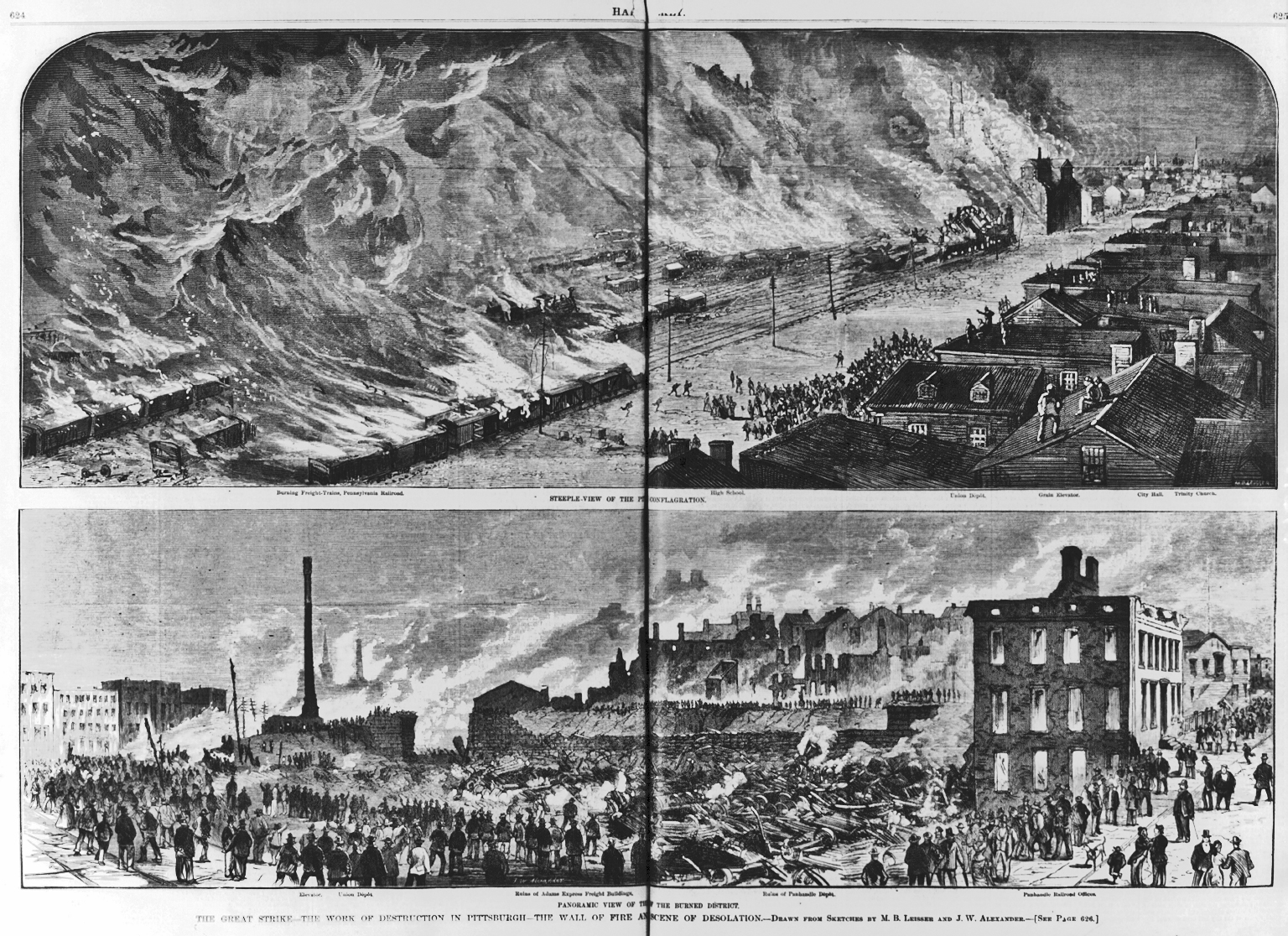

Early on the morning of July 21st, 600 soldiers departed for the Steel City, acquiring two Gatling Guns and ammunition along the way in Harrisburg. This set the stage for the day's later events, which eclipsed Baltimore's bloodshed.

That afternoon the militia arrived and were greeted with a growing crowd of on-lookers, the curious, passers-by, strikers, and sympathizers (many of whom were employed in other trades).

As the crowd became incensed, the troops were ordered to charge with fixed bayonets. Several civilians were stabbed, which only escalated the violence. The crowd then pelted the soldiers with stones whereupon the order was given to open fire.

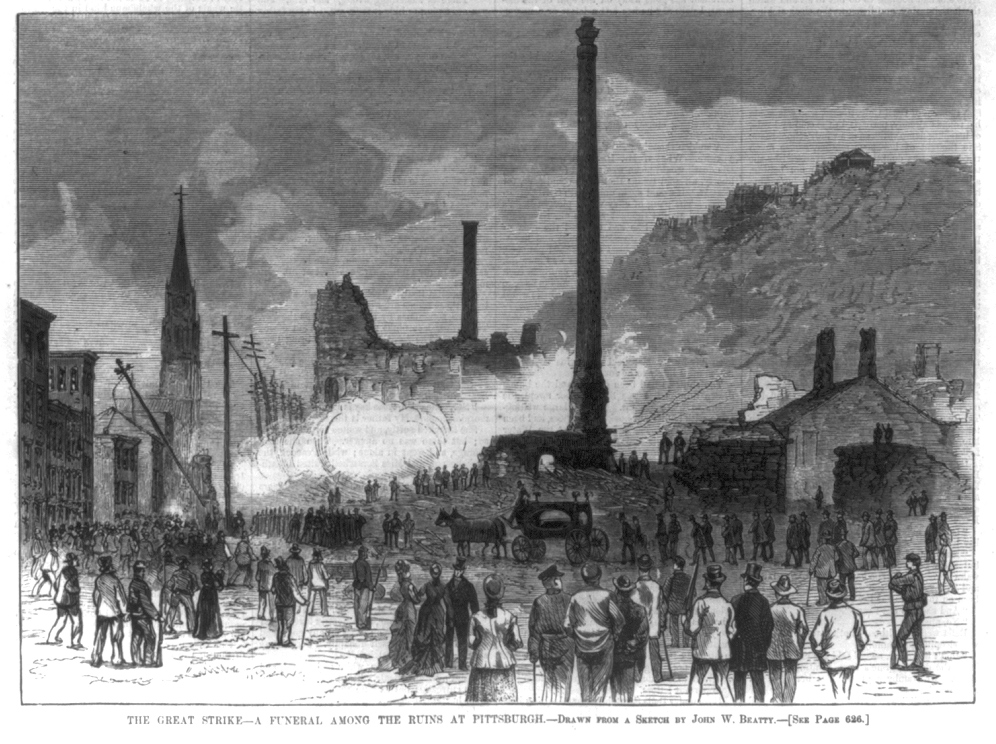

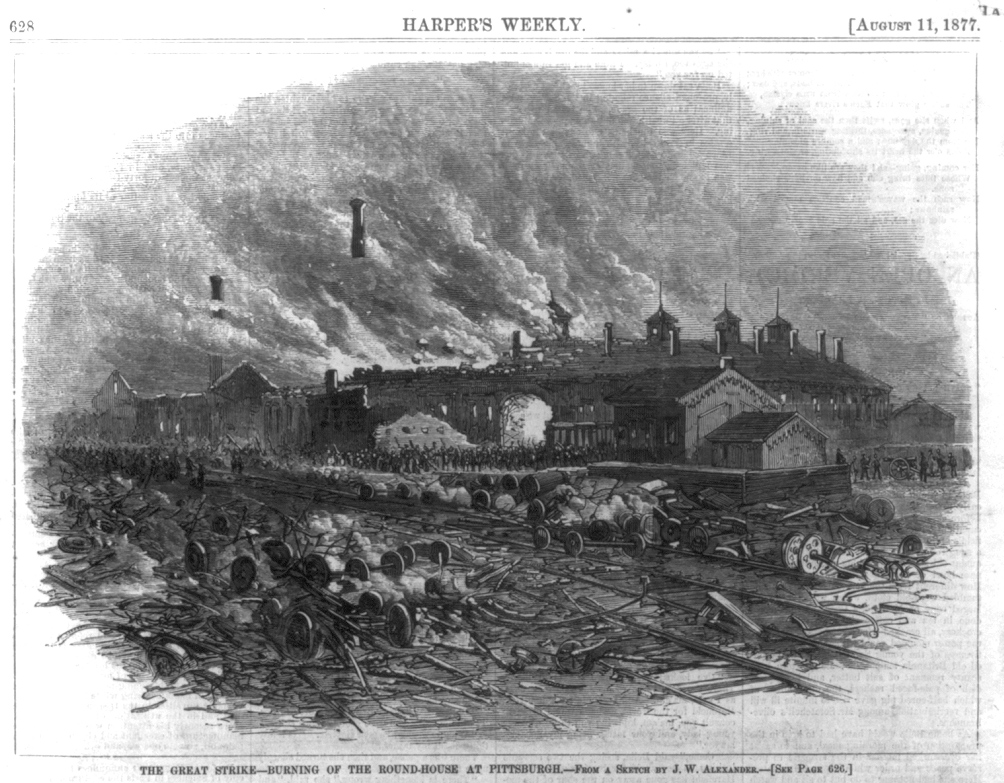

When it was over, 20 people were dead (including one woman and three children) and another 29 injured. Having incited a hornet's nest the soldiers were forced to retreat back into the local roundhouse.

The enraged crowd then began burning railroad property and took great prejudice in destroying everything the PRR owned from the roundhouse to 23rd Street.

In the end, the Pennsylvania Railroad lost 39 buildings, 104 locomotives, 46 passenger cars, and 1,200 freight cars suffering $4.1 million in damages (insurance would cover $3 million).

The militiamen holed up in the roundhouse managed to save the structure, and their lives, by using a water hose. The following morning they finally exited the building, as peace returned to the city.

Interestingly, while more soldiers were brought in it turns out they were not needed as the citizenry by and large policed themselves.

For the PRR, its issues were not over; in nearby Allegheny City, the railroad found itself with another mess. Workers there had also requested arbitration and, after being denied, stopped all traffic.

It was a devastating blow as the town was a major junction point for several PRR affiliates including the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago (PFW&C); Allegheny Valley; and the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati & St. Louis Railway ("The Panhandle"); the B&O's Connellsville Division also reached the town.

The strike was led by PFW&C brakeman Robert Adams Ammon; under his leadership the effort was successful in virtually shutting down PRR's long-distance freight service.

He proved quite effective in his newfound leadership role, wielding a great deal of support from not only fellow workers but also the general public. However, after attempting to return operations to the company on July 24th he was overruled and resigned.

Unrest Elsewhere

With Ammon's departure, strikes along the PRR rapidly disintegrated despite continued public support. The workers may not have been completely aware of what they had started as the strike had now fully engaged the nation.

Throughout Pennsylvania, both railroaders and general laborers struck in an act of unity for better pay and working conditions.

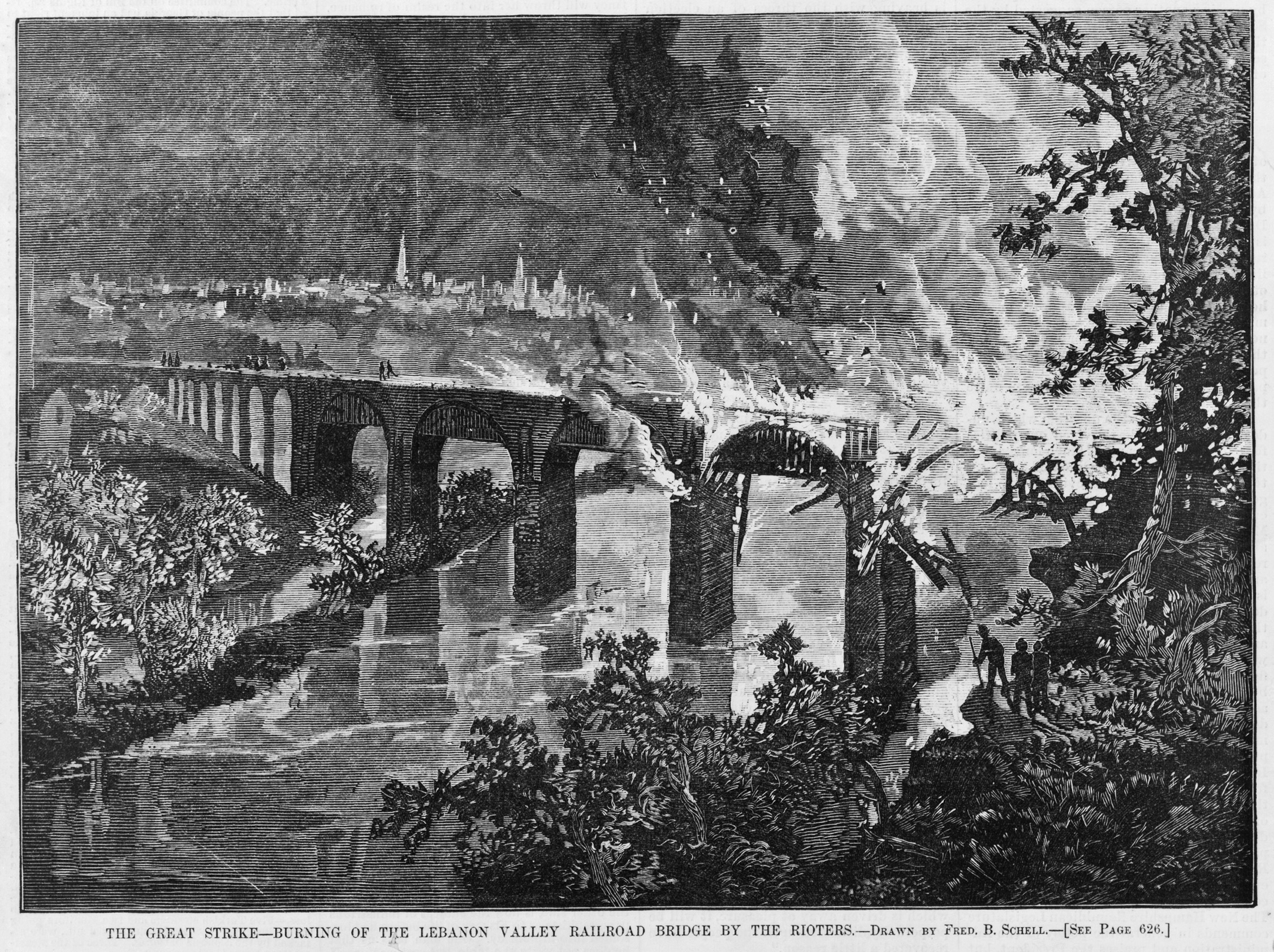

In some cases violence broke out and people were shot although most often the protests were peaceful. While the PRR was attempting to restart regular freight service another incident occurred along the nearby Philadelphia & Reading Railroad (P&R).

Headed by Franklin B. Gowen the P&R was a powerful corporation during the 1870's. It moved substantial anthracite coal from mines in northeastern Pennsylvania and controlled several regional railroads.

In Reading, P&R workers struck on July 22nd after hearing of the unrest in Pittsburgh. Similar to the PRR and B&O, Gowen also refused arbitration. Instead, the P&R president called for the National Guard and was provided Pennsylvania's Second Division.

That evening, a large crowd gathered near the P&R depot at Seventh and Penn Streets to witness the strikers' continued efforts. When troops arrived, a few men pelted them with stones and bricks. The soldiers immediately opened fire and once it was over, some 10 bystanders were killed and another 40 wounded.

Two days following the massacre, 1,500 workers of the Lackawanna Iron & Coal Company, along with firemen and brakemen of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western and Delaware & Hudson railroads, went on strike in Scranton citing wage reductions; by July 29th some 35,000 regional workers were idle!

In a last resort effort to end the stoppage, Scranton Mayor Robert H. McKune formed a hasty militia of 116 citizens referred to as the "Scranton Citizens' Corps."

Once again, shots were fired and before it was over, six miners had been killed. Afterwards, the state sought, and received, federal support with troops arriving on July 27th.

Following 12 days of interruptions, the PRR and Reading returned to normal operations on July 31st while service to Scranton resumed August 2nd (interestingly, the miners continued to strike until forced back to work by the presence of federal troops in mid-October).

A day after PRR's employees walked off the job in Pittsburgh the Erie Railway was faced with a similar situation at Hornellsville, New York.

This town was the junction of its three primary main lines which included the Buffalo Division, Susquehanna Division, and Allegheny Division.

In early June the company, which had been in bankruptcy since shortly after the 1873 panic, informed its employees a 10% pay cut would be enacted as of July 1st. Initially, the workers did nothing.

However, after witnessing the effectiveness of strikes along the B&O, PRR, and elsewhere they demanded their wages be restored.

Not surprisingly, the company (led by Hugh Jewett) refused and workers struck in Hornellsville at 1 PM on July 20th. It began a chain reaction which spread to other major Erie division points.

Once more, the militia was called out; this time by New York's governor, Lucius Robinson. While violence often followed such decisions this was not the case in Hornellsville where the militia did little to stop the strikes.

Eventually, force was enacted when fresh troops of Brooklyn's 23rd Regiment broke up the walkout and the strike ended on July 26th. Since the town was Erie's nerve center, its reopening essentially ended issues elsewhere.

Interestingly, things were not quite over in nearby Buffalo. This town was a major market for several railroads including the Lehigh Valley; Delaware, Lackawanna & Western; New York Central & Hudson River Railroad (NYC&HR), and others.

Following the Erie's strike, NYC&HR workers and those on the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern (LS&MS) walked off the job after suffering their own 10% wage reduction. In an interesting turn of events, president William H. Vanderbilt handled the issue quite differently. In response, he largely chose ignorance and stopped all service.

In the end, between Vanderbilt's disregard and Robinson's force, the strikers lost the fight without having won a single concession. The NYC&HR declared it all over by July 30th, which coincided with the day LS&MS workers also gave up.

Result

Throughout the country there were many other strikes which never enjoyed national coverage such as in Chicago, St. Louis, Columbus, Newark (Ohio), and Indianapolis.

All told, more than 100 people lost their lives during the bloodshed, many of whom were not even striking. Despite being painted as villains virtually all of the walkouts had been peaceful.

On August 5 the Great Railroad Strike Of 1877 was declared over as President Hayes noted, "The strikers have been put down by force..."

While the Great Strike would be deemed a failure from a technical standpoint its long-term prospects were much more encouraging. The working public quickly realized they held the power to shutdown business and the capitalistic system.

This led to a resurgence of organized labor, such as the Workingmen's Party Of The United States (WPUS) and Greenback-Labor Party, both of which sought to elect politicians sympathetic to their cause.

Noteworthy issues included an 8-hour work day, a national agency monitoring the industry, minimum wages, an end to discriminatory hiring practices, eliminating company scrip as wages, and nationalizing railroads.

Significance

Not all were enacted but the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was nevertheless a catalyst which saw many come to pass. The Washington Capital noted the following about the strikes (reprinted in the Martinsburg Statesman on September 4, 1877):

"The late strike was not the work of a mob nor the working of a riot, but a revolution that is making itself felt throughout the land. The afterbirth indicates the serious nature of a nativity. "

"Capitalists may stuff cotton in their ears, the subsidized press may write with apparent indifference, as boys whistle when passing a graveyard, but those who understand the forces at work in society know already that America will never be the same again. For decades, yes centuries to come, our nation will feel the effects of the tidal wave that swept over it for two weeks in July."

In the decades following the strikes, the federal government took a much more hands-on approach in protecting the general laborer. Not only did this lead to a rise in unions but also clamped down on corporations' brutal treatment of workers.

On a broader scale, railroads found themselves under far greater federal scrutiny; the Interstate Commerce Commission was born on February 4, 1887 to regulate interstate commerce while a series of acts passed in the early 20th century further strengthened the ICC's power (Elkins Act of 1903, Hepburn Act of 1906, and Mann-Elkins Act of 1910).

In addition, safety became a much more prominent issue; on March 2, 1893, Congress passed the Safety Appliance Act which went into effect in 1900.

This mandated that all cars be equipped with George Westinghouse's automatic air brake (invented in 1869) and Eli Janney's automatic coupler (invented in 1873). Once put into widespread practice, accidents on the jobs dramatically decreased.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.