Railroads In The 2nd Industrial Revolution (1890s)

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

A multitude of events were affecting the railroad industry during the 1890's:

- A financial panic ensued in 1893, the first federal regulations were enacted that decade.

- A new mode of transportation took root (interurbans).

- Labor made a greater push for fair working conditions.

- A locomotive reached speeds beyond 100 mph (New York Central & Hudson River 4-4-0 #999, which attained a speed of 112.5 miles per hour on May 9, 1893)

- The mighty Southern Railway was born.

In general, what is now regarded as the Second Industrial Revolution was great time in America; business was rapidly expanding (especially in the west) and new construction continued with nearly 30,000 miles completed between 1890 and 1900.

Much of this trackage was laid down across the Midwest and western states, particularly through Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin and eastern Nebraska and Kansas; the so-called "granger railroads."

History

Alas, the building blitzkrieg resulted in a great deal of redundant trackage throughout America's Breadbasket.

As federal regulations tightened, railroads were forced to continue operating many of these branches at a loss until the 1970's and 1980's.

Dr. George W. Hilton points out railroads had reached their economic maturation by the late 19th century and would remain the only viable and efficient mode of transportation until the 1920's.

Images

The Baltimore & Ohio's quaint depot in Friendly, West Virginia is seen here along the former Ohio River Rail Road (Wheeling - Huntington) circa 1920. Author's collection.

The Baltimore & Ohio's quaint depot in Friendly, West Virginia is seen here along the former Ohio River Rail Road (Wheeling - Huntington) circa 1920. Author's collection.Contribution

They dominated every aspect of American commerce. The information here highlights the industry during the 19th century's final decade.

As the 1890's dawned, railroads were riding a great wave of euphoria.

The industry had witnessed more than 70,000 miles of new construction in the 1880's, trains were the undisputed leader in transportation (which drove an economic explosion), rail barons became increasingly richer, and it appeared nothing would slow America's largest industry.

As their power grew into what Dr. Hilton described as a cartel, railroads used their influence to place supportive politicians throughout Washington and at the state level. As a result, complaints by the general public were largely ignored.

At A Glance

First Main Line Electric Enters Service (Baltimore & Ohio, 1895) Legislation Adopts Automatic Air Brake and Coupler (March, 1893) First Electrified Interurbans Appear |

|

7 Miles (1890) 1,538 Miles (1899) |

|

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Hilton, George and Due, John. Electric Interurban Railways in America, The. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

That began to change following the Great Railroad Strike Of 1877. While it did not win concessions for the common worker, Americans recognized the corporate machine could potentially be taken down. Continued efforts eventually led to the Interstate Commerce Commission's formation on February 4, 1887.

In his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," author John F. Stover points out that Richard S. Olney, a corporate attorney, noted the new ICC only "...satisfied the popular clamour for a government supervision of the railroads," but would do nothing in actually dampening their power.

At first, Olney's words rang true but over time they were proven wrong as further acts ended railroads' free reign.

Important Inventions

The decade's most important legislation was in the area of safety.

As Jim Boyd notes in his book, "The American Freight Train," the Railway Safety Appliance Act of 1893, passed by Congress that year, federally mandated all rail equipment include two important devices, George Westinghouse's automatic air brake and Eli Janney's automatic knuckle coupler (also known as the Master Car Builders, or MCB, coupler).

Both were revolutionary as the most practical and efficient way to stop a train and join/detach equipment.

The former had been tested as early as 1869 and the latter in 1873 but railroads continually refused to use either citing cost concerns. The decade's only significant downturn was the financial Panic of 1893.

There were many reasons for this particular depression, some of which were international in nature. For the railroad industry, it all began when the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, a mighty northeastern anthracite carrier which had been attempting to create a regional monopoly, entered receivership on February 20, 1893.

This sparked a domino effect that witnessed 40,000 miles of railroad in bankruptcy that year including the Erie Railway, Baltimore & Ohio, Northern Pacific, Richmond & Danville, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific. While recovery took time the panic was not nearly as severe as the 1873 incident.

Strikes At The Pullman Palace Car Company

The strikes at George Pullman's Pullman Palace Car Company in May, 1894 were not directly related to the railroad industry but would eventually involve railroaders. It also signified another shift towards organized labor gaining concessions against the corporate empire.

If you have any interest in this subject, its history, and effects on American society you should consider a copy of Jack Kelly’s book, “The Edge Of Anarchy.”

It covers these subjects and specifically details the great uprising which began when workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company walked off the job in a fight for higher wages.

The battle soon escalated into a nationwide strike involving American Railway Union’s 150,000 members, led by Eugene V. Debs. Mr. Kelly’s book eloquently details the struggle, which ultimately ended in failure when the U.S. government dispatched federal troops to quell the unrest.

While “The Edge Of Anarchy” is a fascinating look at a different time in America it also highlights similarities to labor issues in modern times. Without this fight, the industry's modern labor movement in the 20th century would likely never have been successful.

A significant positive event did result from the depression, creation of the Southern Railway.

After the Richmond & Danville's struggles, the Southern was born in 1894 through the efforts of banking mogul J.P. Morgan; it was comprised of the original R&D along with several smaller systems that, combined, formed a 6,000 mile system.

Morgan used his extensive assets to spent heavily on upgrading the new conglomerate. After the initial merger the Southern continued to grow, peaking at nearly 6,500 miles by 1900.

During the 20th century it became one of the most profitable railroads of all time before its merger with the Norfolk & Western in 1982 (forming today's Norfolk Southern Railway).

In its final incarnation the railroad stretched from Richmond to Jacksonville, Memphis to New Orleans, Washington to Atlanta, St. Louis to Chattanooga, and was comprised of some 125 smaller railroads. Its most important main line linked Atlanta with Washington, D.C. and was entirely double-tracked.

Two other systems that helped rebuild the South were the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line. The former, also known as the ACL or 'Coast Line,' served points from Richmond to Florida and west to Birmingham, Alabama.

A crowd has gathered at the new depot in New Martinsville, West Virginia to celebrate the opening of the Baltimore & Ohio's Clarksburg Northern Railroad on February 26, 1914. Author's collection.

A crowd has gathered at the new depot in New Martinsville, West Virginia to celebrate the opening of the Baltimore & Ohio's Clarksburg Northern Railroad on February 26, 1914. Author's collection.The Seaboard Air Line is perhaps best remembered as a smaller version of the ACL; both railroads served many of the same cities. The long-time competitors would eventually merge in 1967 forming the Seaboard Coast Line.

The industry in the 1890's saw two major improvements. Firstly, railroads began switching to steel rails in favor of iron.

Steel, created from molten pig iron (before the development of the open hearth furnace), was not only much stronger but also had a longer lifespan. The modern steel movement is credited to Englishmen Henry Bessemer, who invented the so-called "Bessemer Process" in 1857.

It was the first of its kind enabling steel to be produced cheaply on a large scale. A license for his process was acquired by Alexander Lyman Holley, an American mechanical engineer, which brought steel-making to the United States in 1863. He, along with John F. Winslow and John Augustus Griswold, placed the first steel mill into operation at Troy, New York in 1865.

Afterwards, the use of steel rail rose sharply; in 1880 about 25% of America's rail network consisted of steel rails. This number had jumped to 80% by 1890, and by 1900 nearly all corridors were laid with steel.

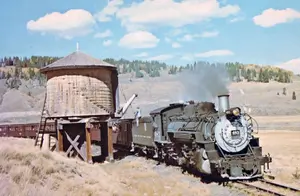

Seen here is Baltimore & Ohio's water tower and pump station at Foster, West Virginia in the early 1900s. Author's collection.

Seen here is Baltimore & Ohio's water tower and pump station at Foster, West Virginia in the early 1900s. Author's collection.Electric Locomotives

The decade's other advancement was the electric locomotive's introduction, first employed by the B&O. The Baltimore Belt Railroad and Howard Street Tunnel project essentially kicked off main line electrification in the United States.

Its origins can be traced as far back as the 1830's although modern electrified operations began with Frank Sprague's successful demonstrations on the Richmond Union Passenger Railway in 1888.

The Baltimore Belt Railroad, was built to close a gap between the railroad’s New York-Washington (north-south) and Washington-Cumberland (east-west) main lines. To learn more about the B&O's electrified operations, please click here.

Prior to this the railroad relied on a circuitous car ferry operation across Baltimore Harbor, making competition against nearby rival Pennsylvania Railroad nearly impossible.

As Dr. George Hilton and John Due's authoritative piece, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," points out the birth of the true American interurban began around the same time, in 1886, when the same Frank Sprague was involved with another, the New York Elevated Railway.

There, he developed an electric motorcar whereby the traction motor was situated between the axle, along with a trolley pole and multiple-unit control stand.

A view of the small depot in Ravenswood, West Virginia around the turn of the 20th century. The train is either the Ohio River Rail Road or successor Baltimore & Ohio. Author's collection.

A view of the small depot in Ravenswood, West Virginia around the turn of the 20th century. The train is either the Ohio River Rail Road or successor Baltimore & Ohio. Author's collection.Streetcar Development

This gave way to the typical streetcar which became such a common sight throughout America.

There were three great periods of interurban development; the first occurred during the 1890's and reached a great flurry of construction between 1901 and 1904 when more than 5,000 miles were laid down.

The Panic of 1903 ended this fervor but it reignited again between 1905 and 1908 when another 4,000 miles were built. There was one casualty of the 1890's, the narrow gauge railroad.

In another book by Dr. Hilton entitled, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," he details this unique movement, which sprang up during the 1870's.

It reached its zenith in 1885 when 11,699 miles were placed into operation. Proponents felt it a more efficient alternative to the standard gauge of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches. However, their data was later proven flawed and by 1890, mileage had tumbled to 8,757 as lines were either abandoned or converted.

By 1900 this number had decreased to just 6,733. In 1900 the country's total rail mileage had increased from 163,597 (1890) to 193,346.

By this time the railroad industry was so well entrenched that it seemed rails reached every small community of the country, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast.

The era would see several east-west and north-south main lines in operation including no less than five routes connecting the west coast. Revenues by this time had topped $1 billion with three quarters of a million workers employed on the railroad. By the 20th century this number continued to increase.

Recent Articles

-

New York & Lake Erie Unveils M636 No. 636 In New Colors (2025)

Feb 17, 26 02:05 PM

In mid-May 2025, railfans along the former Erie rails in Western New York were treated to a sight that feels increasingly rare in North American railroading: a big M636 in new paint. -

First Siemens “Northlander” Trainset Arrives In Ontario

Feb 17, 26 11:46 AM

Ontario’s long-awaited return of the Northlander passenger train took a major step forward this winter with the arrival of the first brand-new Siemens-built trainset in the province. -

Sound Transit Set to Launch Cross-Lake Service

Feb 17, 26 10:09 AM

For the first time in the region’s modern transit era, Sound Transit light rail trains will soon carry passengers directly across Lake Washington -

Michigan’s Old Road Dinner Train Still Seeks New Home

Feb 17, 26 10:04 AM

In May, 2025 it was announced that Michigan's Old Road Dinner Train was seeking a new home to continue operations. As of this writing that search continues. -

WMSR Acquires Conemaugh & Black Lick SW7 No. 111

Feb 17, 26 10:00 AM

In a notable late-summer preservation move, the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) announced in August 2025 that it had acquired former Conemaugh & Black Lick Railroad (C&BL) EMD SW7 No. 111. -

MBTA Unveils New Haven-Inspired Locomotive

Feb 17, 26 09:58 AM

he Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority has pulled back the curtain on its newest heritage locomotive, F40PH-3C No. 1071, wearing a bold, New Haven–inspired paint scheme that pays tribute to the… -

Ohio's Dinner Train Rides At The CVSR!

Feb 17, 26 09:56 AM

While the railroad is well known for daytime sightseeing and seasonal events, one of its most memorable offerings is its evening dining program—an experience that blends vintage passenger-car ambience… -

Missouri Dinner Train Rides In Branson

Feb 17, 26 09:53 AM

Nestled in the heart of the Ozarks, the Branson Scenic Railway offers one of the most distinctive rail experiences in the Midwest—pairing classic passenger railroading with sweeping mountain scenery a… -

Texas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:49 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:48 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

RTA To Become The Northern Illinois Transit Authority

Feb 16, 26 12:49 PM

Later this year, the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)—the umbrella agency that plans and funds public transportation across the Chicago region—will be reorganized into a new entity: the Norther… -

CPKC Holiday Train Sets New Record In 2025

Feb 16, 26 11:06 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City’s (CPKC) beloved Holiday Train wrapped up its 2025 tour with a milestone that underscores just how powerful a community tradition can become. -

Historic Izaak Walton Inn Slated To Close

Feb 16, 26 10:51 AM

A storied rail-side landmark in northwest Montana—the Izaak Walton Inn in Essex—appears headed for an abrupt shutdown, with employees reportedly told their work will end “on or about March 6, 2026.” -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils Restored American Freedom Train No. 1

Feb 16, 26 10:31 AM

The B&O Railroad Museum has completed a comprehensive cosmetic restoration of American Freedom Train No. 1, the patriotic 4-8-4 steam locomotive that helped pull the famed American Freedom Train durin… -

Union Pacific, Wabtec Ink $1.2B Deal To Modernize AC4400 Fleet

Feb 16, 26 10:25 AM

Union Pacific has signed a $1.2 billion agreement with Wabtec to modernize a significant portion of its GE AC4400 fleet, doubling down on the strategy of rebuilding proven high-horsepower road units r… -

CSX Taps Wabtec For $670M Locomotive And Digital Upgrade

Feb 16, 26 10:19 AM

CSX Transportation says it is moving to refresh and standardize a major piece of its operating fleet, announcing a $670 million agreement with Wabtec. -

New Mexico "Dinner" Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 10:15 AM

If your heart is set on clinking glasses while the desert glows at sunset, you can absolutely do that here—just know which operator offers what, and plan accordingly. -

West Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Elkins

Feb 16, 26 10:13 AM

The D&GV offers the kind of rail experience that feels purpose-built for railfans and casual travelers. -

Indiana Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 10:11 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 09:52 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

West Side Lumber Shay No. 12 Heads Home

Feb 16, 26 09:48 AM

A century-old survivor of Sierra Nevada logging railroading is returning west, recently acquired by the Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine Railroad. -

Building A T1 Again: The PRR 5550 Project

Feb 15, 26 06:10 PM

Today, a nonprofit group, the PRR T1 Steam Locomotive Trust, is doing something that would have sounded impossible for decades: building a brand-new T1 from the ground up. -

PRR T1 No. 5550’s Cylinders Nearing Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:53 PM

According to a project update circulated late last year, fabrication work on 5550’s cylinders has advanced to the point where they are now “nearing completion,” with the Trust reporting cylinder work… -

Santa Fe 3415's Rebuild Nears Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:14 PM

One of the Midwest’s most recognizable operating steam locomotives is edging closer to the day it can lead excursions again. -

Ohio Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:59 AM

Among Lebanon Mason & Monroe Railroad's easiest “yes” experiences for families is the Family Pizza Train—a relaxed, 90-minute ride where dinner is served right at your seat, with the countryside slidi… -

Wisconsin Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:57 AM

Among Wisconsin Great Northern's lineup, one trip stands out as a simple, crowd-pleasing “starter” ride for kids and first-timers: the Family Pizza Train—two hours of Northwoods views, a stop on a tal… -

Illinois "Pizza" Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:55 AM

For both residents and visitors looking to indulge in pizza while enjoying the state's picturesque landscapes, the concept of pizza train rides offers a uniquely delightful experience. -

Tennessee's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:50 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:48 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Staunton!

Feb 15, 26 10:46 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a classic scenic train ride with a genuinely satisfying meal—served at your table while the countryside rolls by—the Virginia Scenic Railway was built for you. -

New Hampshire's Dinner Train Rides In N. Conway

Feb 15, 26 10:45 AM

Tucked into the heart of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Valley, the Conway Scenic Railroad is one of New England’s most beloved heritage railways. -

Union Pacific 4014 Begins Coast-To-Coast Tour

Feb 15, 26 12:30 AM

Union Pacific’s legendary 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 is scheduled to return to the main line in a big way this spring, kicking off the railroad’s first-ever coast-to-coast steam tour as part of a broa… -

Amtrak Introduces The Cascades Airo Trainset

Feb 15, 26 12:11 AM

Amtrak pulled the curtain back this month on the first trainset in its forthcoming Airo fleet, using Union Station as a stage to preview what the railroad says is a major step forward in comfort, acce… -

Nevada Northern Railway 2-8-0 81 Returns

Feb 14, 26 11:54 PM

The Nevada Northern Railway Museum has successfully fired its Baldwin-built 2-8-0 No. 81 after a lengthy outage and intensive mechanical work, a major milestone that sets the stage for the locomotive… -

Metrolink F59PH 851 Preserved In Fullerton, CA

Feb 14, 26 11:41 PM

Metrolink has donated locomotive No. 851—its first rostered unit—to the Fullerton Train Museum, where it will be displayed and interpreted as a cornerstone artifact from the region’s modern passenger… -

Oregon's Dinner Train Rides Near Mt. Hood!

Feb 14, 26 09:16 AM

The Mt. Hood Railroad is the moving part of that postcard—a century-old short line that began as a working railroad. -

Maryland's Dinner Train Rides At WMSR!

Feb 14, 26 09:15 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) has become one of the Mid-Atlantic’s signature heritage operations—equal parts mountain railroad, living museum, and “special-occasion” night out. -

Colorado Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:13 AM

If there’s one weekend (or two) at the Colorado Railroad Museum that captures that “living history” spirit better than almost anything else, it’s Wild West Days. -

South Dakota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:11 AM

While the 1880 Train's regular runs are a treat in any season, the Oktoberfest Express adds an extra layer of fun: German-inspired food, seasonal beer, and live polka set against the sound and spectac… -

Kentucky Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:10 AM

One of KRM’s most crowd-pleasing themed events is “The Outlaw Express,” a Wild West train robbery ride built around family-friendly entertainment and a good cause. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:08 AM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Indiana "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:06 AM

Indiana offers a unique opportunity to experience the thrill of the Wild West through its captivating train rides. -

B&O Observation "Washington" Cosmetically Restored

Feb 14, 26 12:25 AM

Visitors to the B&O Railroad Museum will soon be able to step into a freshly revived slice of postwar rail luxury: Baltimore & Ohio No. 3316, the observation-tavern car Washington. -

Southern 2-8-2 4501 Returns To Classic Green

Feb 14, 26 12:24 AM

Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum officials announced that Southern Railway steam locomotive No. 4501—the museum’s flagship 2-8-2 Mikado—will reappear from its annual inspection wearing the classic Sou… -

Illinois Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:04 PM

Among Illinois's scenic train rides, one of the most unique and captivating experiences is the murder mystery excursion. -

Vermont ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:00 PM

There are currently murder mystery dinner trains offered in Vermont but until recently the Champlain Valley Dinner Train offered such a trip! -

Missouri Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 11:47 AM

Among the Iron Mountain Railway's warm-weather offerings, the Ice Cream Express stands out as a perfect “easy yes” outing: a short road trip, a real train ride, and a built-in treat that turns the who… -

Florida "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:53 AM

This article delves into wild west rides throughout Florida, the historical context surrounding them, and their undeniable charm. -

West Virginia "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:49 AM

While D&GV is known for several different excursions across the region, one of the most entertaining rides on its calendar is the Greenbrier Express Wild West Special. -

Alabama "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:47 AM

Although Alabama isn't the traditional setting for Wild West tales, the state provides its own flavor of historic rail adventures that draw enthusiasts year-round.