"ACE 3000" Steam Locomotive: Prototype, History, Horsepower

Last revised: February 22, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The most ambitious attempt to see main line steam locomotives return to regular freight service was the ACE 3000 project of the 1980s. It was first conceived by Ross Rowland, Jr. during the 1970s as the United States saw gas and petroleum prices skyrocket due to an oil embargo.

Rowland, which had overseen the restoration of steam for use on the American Freedom Train, Chessie Steam Special, and other events during that time period was convinced the motive power could be reborn for use in road service.

He formed a new company, the American Coal Enterprises and set about soliciting his idea to railroads, engineers, steam professionals, and other companies in the field of steam/boiler technology.

The idea picked up significant traction during the early 1980s with several backers lined up. Sadly, bickering and a lack of funding doomed the project, which had withered away by the middle of the decade.

By 1980 Ross Rowland was a well-known figure that had made numerous connections within the railroad industry thanks to his efforts in restoring Southern Pacific 4-8-4 #4449 and Reading 4-8-4 #2101 for use on the American Freedom Train.

He was also popular within the railfan community for this reason as well as other steam restorations including Nickel Plate Road #759 and Chesapeake & Ohio #614 (used on Chessie System's Chessie Safety Express).

History

Using these contacts and a belief that steam could not only be a cheaper and more practical means of powering freight trains (again) but also more environmentally friendly Rowland gathered a small team of experts and formed the American Coal Enterprises (ACE) in December of 1980.

Much of Rowland's belief of a revived steam renaissance stemmed from more than just the economics. As he correctly stated, steam manufacturers during the 1940s had never, truly taken the technology to its greatest level of efficiency due to the very fast development of the diesel during the 1930s and 1940s.

Additionally, as Bill Withuhn had pointed out in a long, 13-page article/thesis "Did We Scrap Steam Too Soon?" from the June, 1974 issue of Trains builders had also become lazy and complacent in advancing steam power to effectively compete against the diesel.

With the new motive power's inherent advantages, the industry gave up on research and development by the end of World War II, offering virtually no advertising for steam locomotive products, and doing little more than criticizing General Motors' new FT model.

For instance, during exhaustive tests by the New York Central during 1946, between a 4,000 horsepower set of diesels and a Class S-1 Niagara, the cost-per-mile margin between the two was actually quite small.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614-T is eastbound at Thurmond, West Virginia during the "ACE 3000" tests in January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614-T is eastbound at Thurmond, West Virginia during the "ACE 3000" tests in January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.It was also argued that the NYC's 4-8-4s, in this instance, offered "more horsepower per dollar of total expense than the diesel." However, by that time the diesel had an added advantage of perception; it was seen as the wave of the future while steam was looked at as outdated.

Overall, Withuhn's article is quite fascinating and highly recommended although far too long and detailed to cover further here. Of course, diesels had another advantage; less need of infrastructure (water towers, an army of workers to maintain the locomotives, terminals every few hundred miles, etc.) that hampered many railroads' desire to continue running steam.

However, by the 1980s technology had advanced to the point that Rowland and his team believed all of this could be bypassed and that a new steam design could function very similar to the diesel in this regard.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T steams through the yard in Huntington, West Virginia during her "ACE 3000" tests in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T steams through the yard in Huntington, West Virginia during her "ACE 3000" tests in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Rowland's team consisted of some of the best names in the business of steam technology including:

- Livio Dante Porta (an Argentine mechanical engineer who studied under noted French steam designer Andre Chapelon)

- Physicist David Berkowitz

- Bill Withuhn mentioned above who was also an industrial engineer

- Babcock & Wilcox Company, founded in 1867 that helped design the Norfolk & Western's Jawn Henry

- Dr. John T. Harding whose background was in physics and had worked in the FRA's High Speed Ground Transportation program

- And more than a dozen other associates with exemplary backgrounds in transportation or related fields.

As the team began brainstorming the ACE 3000 concept they ultimately concluded that it was practical and a low-maintenance, economical competitor to the diesel could be built.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614-T leads westbound empties over the New River at Hawks Nest, West Virginia during the ACE 3000 tests in January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614-T leads westbound empties over the New River at Hawks Nest, West Virginia during the ACE 3000 tests in January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.It was Porta, himself, that drafted the first concept that became known as the original ACE 3000, or Second Generation Steam (SGS) locomotive.

The general consensus of the locomotive's design was that it would:

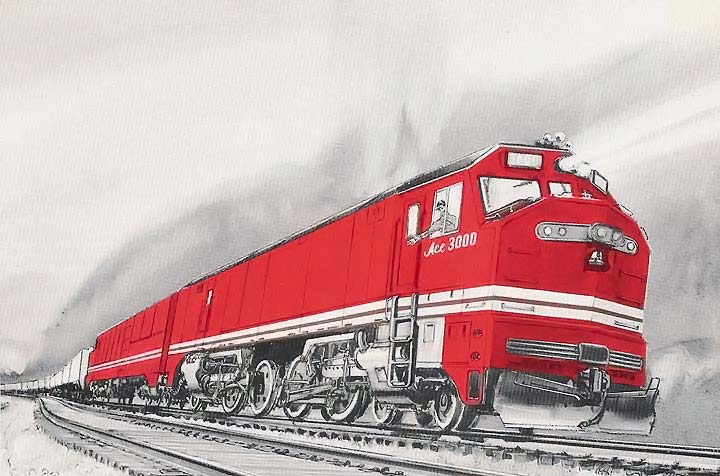

- Feature a 2-10-0 wheel arrangement, burn coal, operate at high speeds in freight service (15 to 70 mph)

- Carry a look not unlike a conventional diesel with a semi-streamlined cab design

- Feature 3,000 nominal drawbar horsepower and 4,000 at its peak (based from the, then standard GP40 series)

- Use the latest in advanced computer technology to still allow the standard crew size of the day

A drawing of the locomotive was done by Gil Reid showing it pulling an intermodal freight at speed and it was from that point interest within the railroad community began to seriously gain traction, at first by Burlington Northern.

However, BN was looking for something a little different than Porta's original 2-10-0. Instead, the parties worked together and came up with what was termed the ACE 3000-8, a 4-8-4+4-8-4 trainset that was a double-ended, streamlined design. Between the locomotives the design called for a small car which would be used to haul the coal (similar to a tender).

Just like with the original ACE 3000, the 3000-8 would use compound expansion, which offered more efficient applications of steam and water if designed correctly (as believed was possible by the 1980s). This type of steam technology was first developed in the U.S. in 1904 with the B&O's "Old Maude" 0-6-6-0 #2400.

However, most railroads shied away from compound expansion at the time since it was too complicated and offered little advantages over simple expansion.

With Burlington Northern's interest growing other major backers began to appear including the C&O/Chessie System and Babcock & Wilcox (B&W). By November of 1982 prototypes were in the works, which were to be ready for service by 1985.

Unfortunately, while no one realized it, this proved the pinnacle of the project. A year later during the spring of 1983 the Coal Oriented Advanced Locomotive Systems (COALS) group was formed with BN, Chessie, and B&W primary stakeholders since ACE simply did not have the resources to fund the multimillion endeavor.

This setback left the company essentially on the outside looking in and only providing the locomotive design itself. As quickly as the project had progressed it fell apart just as rapidly; during the fall of that year it was announced COALS would break up since the parties could not agree on the project's financing.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T stretchers her legs during the "ACE 3000" tests in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T stretchers her legs during the "ACE 3000" tests in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.This put the ACE 3000 endeavor back, squarely on the shoulders of Rowland and his team. While they believed a working prototype could sell the new steam technology the small company just did not have the millions of dollars in funding necessary to do so.

In any event, Rowland was able to put something on the rails for testing in an effort to gain publicity and hopefully fund the project; his own C&O 4-8-4 #614T.

On January 2, 1985 armed with an army of gadgets and technical equipment to gather data concerning the efficiency of the Greenbrier in service it left the C&O main line at Huntington, West Virginia heading east towards Hinton. The bitterly cold temperatures during the trials and issues with the #614T made the tests somewhat inconclusive but the big 4-8-4 overall ran relatively well.

Ultimately, the results of those trials were never published but Rowland and his team did determine, incredibly, that the steamer used less fuel than a comparable Electro-Motive diesel from that era (the GP40).One of American Coal Enterprises' final designs was the most attractive, visually, referred to as the ACE Mark I or ACE 6000.

The locomotive's design was primarily the work of Porta, once again, and it was intended for use in fast-freight service. The steamer was to be a 2-10-2 semi-articulated, double-ended setup capable of producing 6,000 horsepower.

With streamlined shrouding the locomotive it actually more closely resembled an EMD locomotive according to an artists' rendition of the design.

Further refinements, though, to the Mark I saw it converted into a Garratt configuration (an articulated steamer with three parts whereby the boiler sits between a pair of axles on each end of the locomotive).

With this latest change the Chessie System began losing interest in the project, the only remaining railroad still on-board with the concept.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T hustles away from the photographer on the Chesapeake & Ohio main line during the "ACE 3000" tests outside of Huntington, West Virginia in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614T hustles away from the photographer on the Chesapeake & Ohio main line during the "ACE 3000" tests outside of Huntington, West Virginia in late January, 1985. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.By the mid-1980s oil prices had began falling, which sealed the fate of the ACE 3000. Soon after, Chessie pulled the plug of its financial support and having never received public money to finance the concept American Coal Enterprises foundered.

It was ultimately never able to put a working prototype into service, which was estimated to cost $1.25 million per unit. The ACE had the data on their side, enough so anyway to at least push forward in producing an example of their concept.

However, with limited funds, a small design team, and lack of support/interest from most of the railroad industry they were never able to show the world their idea. Since the 1980s it is said Rowland still hasn't given up on his ACE 3000 project but has also never been able to draw renewed interest.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.

- Home ›

- Locomotives ›

- ACE 3000