Chicago, Aurora and Elgin Railroad: Map, Timetables, Photos

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Chicago, Aurora and Elgin Railroad was once a first-class operation which provided the Fox River Valley with high-speed service into Chicago. It was well-financed from the start, backed by two powerful eastern syndicates.

With money to spend the system was built to incredibly high-standards, carrying a private right-of-way and partially double-tracked main line; west of Wheaton, branches fanned out to the river communities of Elgin, Aurora, Geneva, and Batavia.

In addition, planners settled on a third rail operation which earned it the nickname, "Great Third Rail." Until World War I the CA&E was relatively profitable but then suffered from ridership losses and rising costs.

The years after the depression were a struggle although the fatal blow proved to be the Eisenhower Expressway. It not only hurt ridership but also eliminated the interurban's direct route into Chicago's Loop.

After a drawn out fight the company abruptly ended passenger service without warning on July 3, 1957. The carload freight business continued but could not outpace expenses and operations ceased entirely a few years later.

Photos

A pair of Chicago, Aurora & Elgin steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, work the Indiana Harbor Belt interchange at Bellwood, Illinois in March, 1959. Gordon Lloyd photo.

A pair of Chicago, Aurora & Elgin steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, work the Indiana Harbor Belt interchange at Bellwood, Illinois in March, 1959. Gordon Lloyd photo.History

What became the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin was envisioned as a bridge line, if you will, linking the interurban network already serving the Fox River communities with downtown Chicago.

According to Dr. George Hilton's and John Due's book, "The Electric Interurban Railways in America," these towns, which blossomed into Windy City suburbs, had enjoyed electrified rail service long before the CA&E was built; during the early 1890's the first segment opened between Carpentersville and Elgin, followed by a southward extension to Geneva completed in July of 1896.

At A Glance

Chicago - Wheaton Bellwood - Westchester Wheaton - Elgin Lakewood - St. Charles - Geneva Wheaton - Aurora Batavia Junction - Batavia |

|

Finally, rails reached Aurora in 1899 with a branch to Yorkville put into service during 1901. The property, while carrying a great deal of its own right-of-way, was largely financed by local interests, and built to the typical light construction standards inherent of most interurbans.

In 1901 the Fox River lines were acquired by the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum Syndicate which reorganized them as the Elgin, Aurora & Southern Traction Company. In 1906 the EA&ST was consolidated into the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago (CA&E's immediate predecessor) becoming its Fox River Division.

Construction

The Chicago, Aurora & Elgin began as two separate, paper corporations. On February 24, 1899 members of the Everett-Moore Syndicate incorporated both the Aurora & Chicago Railway and Elgin & Chicago Railway; each had intentions of building east from the Fox River to connect their respective communities with Chicago.

The very next day, February 25, 1899, associates involved with the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum Syndicate formed the Chicago, Wheaton & Aurora Railroad (CW&A) as competition against the Everett-Moore's endeavors. Both groups were relatively well-financed, acquiring the needed franchises and right-of-way in short order.

On February 21, 1901 Pomeroy-Mandelbaum formed another subsidiary known as the Batavia & Eastern Railway to build a branch off its CW&A line into Batavia.

Thankfully, common sense prevailed early on; in 1901 both syndicates agreed to merge operations into a single entity, the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago Railway (AE&C), created on April 10, 1901. This new company absorbed all previous charters, as well as the aforementioned Fox River lines.

Logo

The AE&C was rare for an interurban by receiving strong financial backing right from the start. This largely explains how it survived decades after many others had been abandoned.

Most interurbans were initially capitalized between $10,000 and $100,000 but the AE&C enjoyed an incredible $3 million in startup funding.

With such deep pockets, engineers set about designing a corridor that arguably even surpassed that of the surrounding standard railroads. According to Larry Plancho's excellent book, "The Story Of The Chicago, Aurora & Elgin Railroad: 2 - History," it was planned to operate via third-rail with speeds reaching 65 mph.

At the time, the Midwest's electrical grid was still relatively sporadic, which led to construction of its own power plant at Batavia. An unexpected benefit of this plan turned out to be additional revenue by selling power to third parties.

Another early decision was the location of the AE&C's primary shops and maintenance facilities. It was decided these would be based in Wheaton, the central point of the system, where the Fox River branches met before heading east towards Chicago.

A pair of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, were photographed here at the road's shops in Wheaton, Illinois, circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, were photographed here at the road's shops in Wheaton, Illinois, circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.Construction of the AE&C had actually commenced under the AW&C banner which began building right-of-way northeastward from Aurora on September 18, 1900. This was then continued under the AE&C.

Interestingly, officials did not experience considerable push-back from the standard railroads regarding right-of-way crossings, an issue interurbans often dealt with.

Perhaps it was due to the system's high quality of construction, which included fully protected interlockings; whatever the case, by 1902 the 32.5 miles from Chicago's 52nd Avenue to Aurora, which included double-tracking as far as Wheaton, was completed and ready for service.

Following a series of tests, trials, and troubleshooting operations officially launched on August 25, 1902. That year also marked another important event when the Everett-Moore Syndicate, always the financially stronger of the two, sold-out after the company experienced monetary troubles which left Pomeroy-Mandelbaum as the primary owner. The first branch to open was the Batavia line, put into operation at the end of September that year.

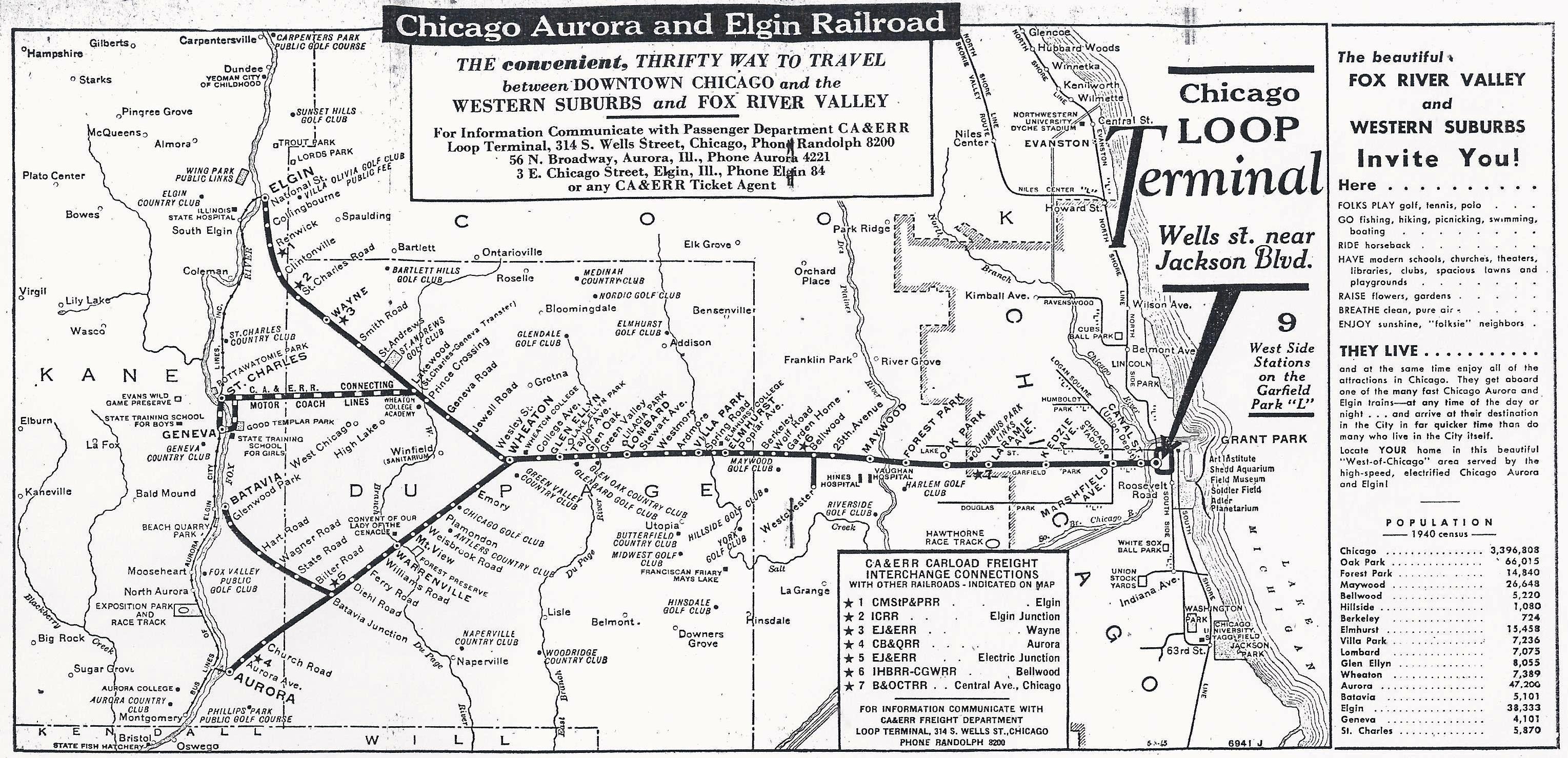

System Map (1946)

Following this event the northwestern 17.5-mile leg into Elgin officially opened just a year later on May 26, 1903. This left only the Geneva Branch. The AE&C's lines beyond Wheaton were not double-tracked although were operated via third-rail.

The branch to Geneva was the only one not served by its own substation since the corridor had not been built by A&EC interests. It was originally incorporated as the Chicago, Wheaton & Western Railway (CW&W) on August 27, 1908 to head west from a point along the AE&C's Elgin Branch (which became Geneva Junction) to West Chicago.

While construction commenced quickly the CW&W never operated its own equipment. Instead, its promoters agreed to hand these duties off to the AE&C which went on to officially lease the CW&W on June 3, 1910.

By December of 1909 rails had reached Geneva and the following year, on July 25, 1910, service was extended to St. Charles under catenary of the Fox River Division.

The Aurora, Elgin & Chicago's management contemplated many times, on a few occasions seriously, about extending service far beyond the Fox River Valley.

However, they ultimately decided against such ideas due to low ridership projections. In any event, their initial assessment of a profitable system linking the Fox River with Chicago was proven correct as patronage was strong from the start.

Electrification and Substations

When built, the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago's electrical components were supplied entirely through General Electric.

The coal-fired power plant produced three-phase, alternating current at 26,000 volts. This was stepped down to single-phase direct current at 600 volts via six substations which carried transformers and generators for this purpose.

These six substations included #1 on the north side of Aurora, #2 at Warrenville, #3 at Lombard, #4 at Maywood, #5 at Ingalton, and #6 at Clintonville.

During the 1920's, under the direction of new leader Dr. Thomas Conway, Jr., more were needed which gave way to new facilities at Wheaton and Bellwood while the Maywood building was expanded.

In 1909 the power plant was also expanded to meet demand. In addition, it supplied power to other area interurbans and for general use. The power plant was later sold in 1926 to the Public Service Company of Northern Illinois. After that time the CA&E contracted out its power needs.

The Chicago "Loop"

By the time service had been established to Geneva the AE&C was already running into Chicago's downtown Loop. As Mr. Plachno points out this single factor is largely why the system was so successful since Fox River commuters could reach the city directly without changing trains in the process.

As early as 1903 the AE&C had been accessing the Loop over tracks of the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad although did not begin formal service into the Fifth Avenue Terminal (this facility opened on October 3, 1904 and it was later renamed the Wells Street Terminal) until March 11, 1905.

Following this event, one final addition was the Cook County & Southern Railway Company (incorporated, November 23, 1905), a 2.25-mile branch running from Bellwood to the Mt. Carmel and Oak Ridge cemeteries. In what would be perceived unusual today, at the time interurbans could derive considerable business from operating funeral trains to such locations.

The Cook County Branch opened on March 18, 1906 but operations survived for only two decades before its replacement by the Westchester Branch which commenced service on October 1, 1926. This line was never operated by either the AE&C or CA&E; instead it was leased to the Chicago Rapid Transit Company.

At its height the AE&C system totaled 66 route miles (Third Rail Division), including all branches and main lines. Its Fox River Division, running north to south (Carpentersville - Elgin - Geneva - Aurora - Yorkville), maintained another 35 route miles. When including all branches, main lines, sidings, city trackage, spurs, etc. the AE&C boasted a network of just under 170 miles.

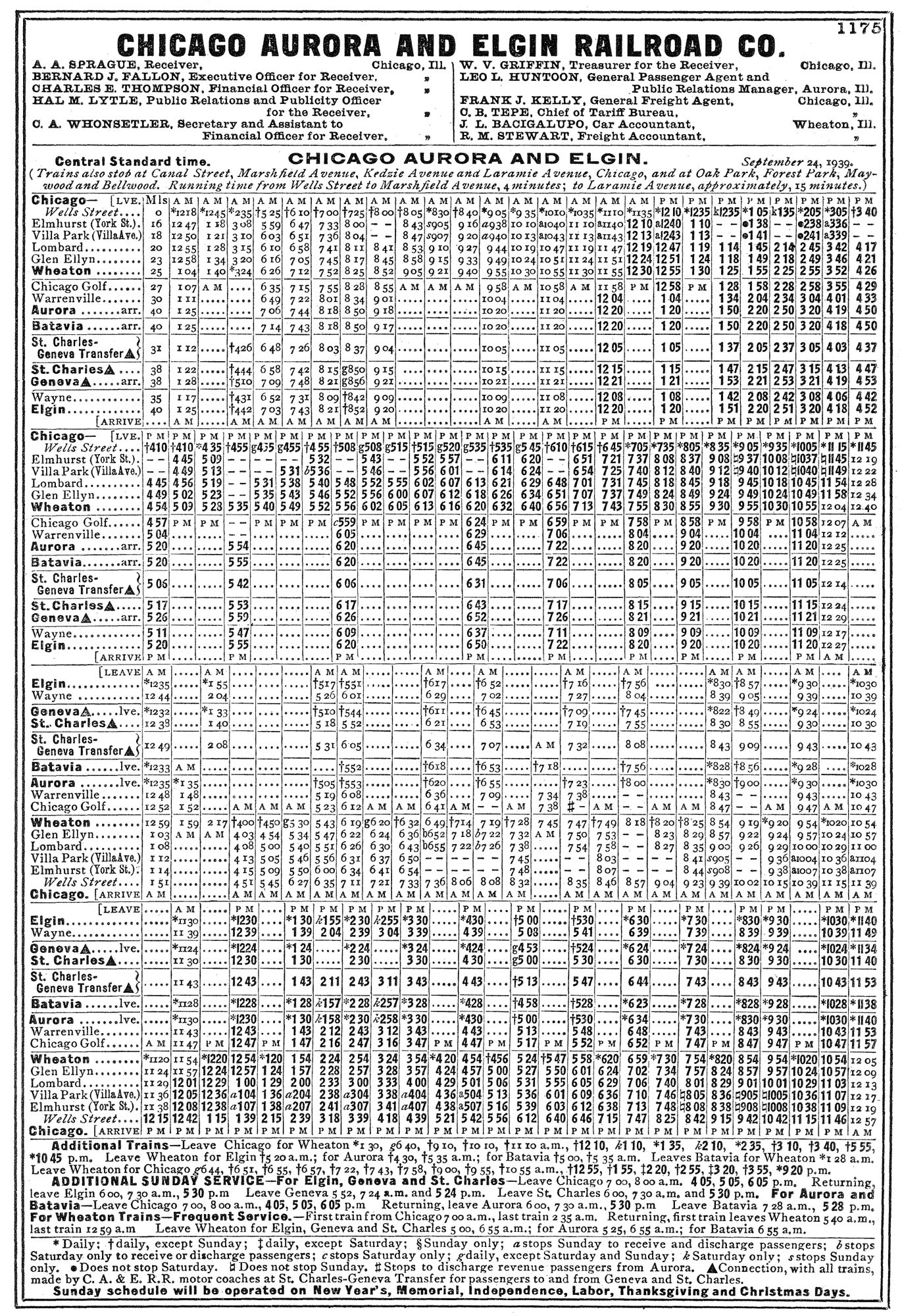

Timetables (1939)

Abandonment of the Cook County Branch was actually not the first cutbacks to take place. The Fox River Division had long fought low ridership, eventually entering bankruptcy in 1919. The property was reorganized as the Aurora, Elgin & Fox River Electric Company in 1924 and then permanently separated from the AE&C.

It continued to struggle as an independent until finally discontinuing all passenger operations on March 31, 1935 (replaced with bus service). The early era of the AE&C was relatively profitable although the interurban never delved heavily into the carload freight business (less-than-carload, or LCL, service did not start until 1905).

But it was an early proponent of milk trains which launched on May 1, 1903 and had initiated express service that same year (October). As a way of further boosting ridership the AE&C running upscale parlor-buffet cars on August 30, 1904.

During the industry's height such extravagances were not uncommon although generally short-lived since standard railroads could outperform interurbans in this market. It proved no different on the AE&C which ended the practice in 1929.

Receivership and the Insull Era

The World War I period was the financial height of the interurban industry, peaking at 15,580 miles in 1916. After that time they slowly declined, squeezed by the new automobile, competition from standard railroads, and the depression years. During July of 1919 AE&C employees went on strike when negotiations over a pay raise could not be settled.

This event, followed by the company's struggles to make interest payments, led to its first bankruptcy on August 9, 1919. On March 16, 1922 the property was sold at foreclosure giving rise to the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin Railroad, which officially took over the AE&C's lines as of July 1st that year. New management brought in Dr. Thomas Conway, Jr. as president.

He immediately put a plan in motion to entirely rebuild the worn-out infrastructure, which had received little attention during the first two decades of operation.

There was new rail laid (some as heavy as 101 pounds), ties replaced, fresh ballast poured, new cars purchased, expansion of the Wheaton Shops, new automatic block signaling installed, and construction of additional substations (see inset paragraph).

Conway's involvement lasted only a few years for in 1926 he moved on to another troubled interurban, the Cincinnati & Dayton Traction Company.

However, he was quite effective during his tenure, returning the Roarin' Elgin to a solid footing. With his departure Samuel Insull's empire gained control and was so impressed with Conway's work that few additional improvements were needed.

Insull's primary involvement centered around electric and gas utilities but he was also a big believer in electrified railroads, ultimately controlling all three of Chicago's major interubans. Altogether, he held interests in 32 states with assets totaling $2 billion.

Despite the CA&E's sinking profits after the Great Depression, Insull's deep pockets helped shield the company from another bankruptcy. His management tried very hard to build up lucrative freight traffic, an area in which the Insull-controlled Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee and Chicago, South Shore & South Bend had been successful.

Unfortunately, despite these efforts CA&E's carload freight never reached $500,000 in any year (by comparison, the South Shore Line was totaling nearly $2 million annually by the start of World War II). In 1930, it peaked at $471,878 from gross total revenues of $2,661,061.

A pair of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, led by #2002, are seen here in freight service near Wheaton, Illinois, circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, led by #2002, are seen here in freight service near Wheaton, Illinois, circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.Final Years

Alas, the Insull era and security it provided were both short-lived. The depression strained his company's finances and bankruptcy soon followed; he resigned control of the Chicago, Auora & Elgin as of June 7, 1932. With the umbrella this protection gone the CA&E also fell into bankruptcy only a month later on July 21st.

This time, receivership persisted throughout the decade and beyond World War II. The CA&E's struggles continued, despite climbing ticket sales as evermore families moved into the western suburbs.

The nature of its clientele, which was transitioning to a commuter base, made them an increasingly unprofitable lot since fares were never high enough to cover all expenses let alone generate a profit.

The nearby South Shore and North Shore were experiencing a similar problem. To help reduce deficits the company successfully discontinued operations over the Geneva Branch, which shutdown after October 31, 1937.

The war years were generally good as business increased to the point the interurban had exited receivership on October 1, 1946, renamed as the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin Railway.

After the war the good times persisted, so much so that a profit of more than $200,000 was expected for 1946. Unfortunately, trouble hit within weeks of exiting receivership when another brief strike occurred due to wage increase demands.

This was eventually granted but plunged the company back into red ink. Then, yet another strike arose in early 1951 for the same reason with all parties finally agreeing to an additional wage hike in March.

Chicago, Aurora & Elgin car #420 has an express run to Chicago, circa 1957. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago, Aurora & Elgin car #420 has an express run to Chicago, circa 1957. American-Rails.com collection.The next significant service reduction was abandonment of the Westchester Branch when the Chicago Transit Authority stopped running the line after December 9, 1951. The Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's end can be tied directly to construction of what was originally known as the West-Side Super Highway, later renamed the Eisenhower Expressway (in honor of President Dwight D. Eisenhower).

Today it is referred to as Interstate 290. The idea for such a highway traced back to the 1930's, designed to connect the downtown area with the western Fox River Valley suburbs; the very same area served by the CA&E.

Just like Southern California's great Pacific Electric Railway, Chicago gave little regard to the interurban's importance as a commuter carrier when planning this freeway. Aside from hurting ridership it also took its right-of-way from Austin Boulevard to Forest Park. In the meantime a temporary right-of-way was built, running east along Van Buren Street.

Not surprisingly, the CA&E was not thrilled with this arrangement due to its service disruptions, numerous grade crossings, and slower running times. It was also unclear where the primary downtown terminal would be situated since the Wells Street Terminal had to be demolished for the project.

The CA&E, which never agreed to the street-running proposal, put forth its own plan. It worked in in conjunction with the CTA to establish a new terminal at Forest Park.

Here, CA&E riders would interchange onto the CTA, and vice-versa. Just after midnight on September 20, 1953 the CA&E's final train pulled out from the Wells Street Terminal and an era came to a close.

The effects of this move were swift and immediate as folks were extremely unhappy with the new arrangement and did not particularly care for CTA's services.

Ridership declined by nearly half; in October of 1952 there were 631,597 riders traveling the CA&E but the following year (October/1953) after the new Forest Park terminal opened this number had dropped to only 350,735.

Already cash-starved, this proved the fatal blow; countless proposals and ideas were put forth to remedy the situation but none adopted. In the meantime, management threatened to end service entirely on its own accord and was only stopped by a court order.

Rosters

The better days brought about by World War II allowed purchase of six new cars from the St. Louis Car Company in November of 1941, #451-456. It was the last new equipment acquired and some of the last such cars ever built for an interurban.

Third-Rail Division

Wooden Passenger Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10-28 (Evens) | Niles | 1902 | Acquired new. |

| 30-58 (Evens) | John Stephenson | 1902 | Acquired new. |

| 101-109 (Odds) | John Stephenson | 1902 | Acquired new. |

| 109 (2nd) | Wheaton Shops | 1906 | Funeral Car |

| 129-130, 133-134, 137 | Jewett | 1907 | ex-Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee ("North Shore Line") |

| 138-141, 144 | American | 1910 | ex-Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee ("North Shore Line") |

| 142-143 | Jewett | 1909 | ex-Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee ("North Shore Line") |

| 201-207 (Odds) | Niles | 1905 | Acquired new. |

| 209 | Wheaton Shops | 1924 | ex-Carolyn Parlor-Buffett |

| 300-308 | Niles | 1906 | Acquired new. |

| 309-310 | Hicks Locomotive Works | 1908 | Acquired new. |

| 311-315 | G.C. Kuhlman | 1909 | Acquired new. |

| 316-321 | Jewett | 1913-1914 | Acquired new. |

Steel Passenger Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400-419 | Pullman | 1923 | Acquired new. |

| 420-434 | Cincinnati | 1927 | Acquired new. |

| 435-436 | Wheaton Shops | 1929 | ex-Parlor-Buffet cars #600-601. |

| 451-460 | St. Louis | 1945 | Acquired new. |

| 600-604 | Cincinnati | 1913 | ex-Washington, Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Railway |

| 700-702 | Cincinnati | 1913 | ex-Washington, Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Railway |

Lightweight Car

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | St. Louis | 1927 | Acquired new. |

Parlor-Buffett Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carolyn (No Number) | Niles | 1905 | Acquired new. |

| Florence (No Number) | Niles | 1906 | Acquired new. |

| 600-601 | Wheaton Shops | 1923 | ex-#305, ex-Florence |

Freight Locomotives

| Car Number | Builder | Type | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001-2002 | General Electric | Steeple-Cab | 1921-1922 | Acquired new. |

| 3003-3004 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab | 1926 | Acquired new. |

| 4005-4006 | Oklahoma Railway | Steeple-Cab | - | Acquired 1955.* |

* Ex-Cedar Rapids & Iowa City Railway (#72-73), Exx-Union Electric Company (#603-604), Nee-Oklahoma Railway (#603-604)

Fox River Division

Single-Truck City Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | St. Louis | Unknown | Acquired 1924, ex-Aurora, Plainfield & Joliet Railway #101 |

| 50-89 | St. Louis | 1923 | Acquired new. |

| 90-97 | St. Louis | 1926 | Acquired new. |

| 108-146 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1902 | Acquired new. |

| 117-127 (Odds) | Briggs | 1893 | ex-Aurora Street Railway. Open design. |

| 131-137 | John Stephenson | 1897 | Acquired new. Open design. |

| 154, 158, 160-166 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1897 | Acquired new. |

| 182 | J.G. Brill | 1897 | Acquired new. |

| 250-258 (Evens) | Niles | 1910 | Acquired new. |

Double-Truck City Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 111-115 (Odds) | J.G. Brill | 1897 | Acquired new. Open design. |

| 144-149 (Odds) | St. Louis | 1894 | Acquired new. Open design. |

| 234-240 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1916 | Acquired new. |

| 242-248 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1913 | Acquired new. |

Double-Truck City/Interurban Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 148, 150 | J.G. Brill | 1898 | ex-Aurora & Geneva Railway |

| 152 | St. Louis | 1894 | Acquired new. |

| 156, 168 | J.G. Brill | 1909 | Acquired secondhand. |

| 170 | J.G. Brill | 1898 | Acquired secondhand. |

| 172 | J.G. Brill | 1898 | Acquired secondhand. |

| 184-188 (Evens) | Pullman | 1894-1895 | ex-Southern Street Railway |

| 190-196 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1908 | Acquired secondhand. |

Double-Truck Interurban Cars

| Car Number | Builder | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100-106 (Evens) | St. Louis | 1901 | Acquired new. |

| 200, 202 | Niles | 1906 | Acquired new. |

| 204, 206 | McGuire-Cummings | 1907 | Acquired new. |

| 208-214 (Evens) | Twin City Rapid Transit | 1899 | ex-TCRT, acquired 5/1913. |

| 216-226 (Evens) | Cincinnati | Unknown | Acquired secondhand. |

| 300-306 | St. Louis | 1924 | Acquired new. |

Above roster information courtesy of the book, "The Great Third Rail," by the Central Electric Railfans' Association (1970 Edition).

Another view of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, and the Wheaton Shops, circa 1959. American-Rails.com collection.

Another view of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin's steeple-cab electrics, #2001 and #2002, and the Wheaton Shops, circa 1959. American-Rails.com collection.Shutdown

But court intervention only delayed the inevitable. The company stated it had lost $2.3 million since closure of the Wells Street Terminal and continued to push for discontinuance. With a grim future outlook, the court granted permission to cease all passenger services on July 3, 1957.

In one of the most extraordinary events ever recorded in the history of interurban operation, CA&E management wasted no time in exercising its opportunity.

At approximately 12:13 PM that day an immediate shutdown was ordered, a move which stranded, confused, and angered thousands of commuters. In the aftermath many were upset but little could be done.

The company tried to persevere as a profitable freight carrier, even contemplating purchasing diesels and scrapping the road's electrification. Unfortunately, there was simply not enough business to do so.

The western area of Chicago had never enjoyed the strong industrial base of its surrounding counterparts, particularly to the south which had allowed the South Shore to prosper.

A petitioned was filed on April 29, 1959 to cease remaining freight services. Between May and June of 1961 separate orders were sent down from the Interstate Commerce Commission and Illinois Commerce Commission granting CA&E the authorization and scrapping crews moved in later that November.

Recent Articles

-

CSX Advances Locomotive Technology to Cut Fuel Use and Emissions

Feb 19, 26 09:43 AM

CSX recently highlighted major progress on its ongoing efforts to reduce fuel consumption, cut greenhouse-gas emissions, and improve operational efficiency across its freight rail network through adva… -

Ohio Railway Museum Unveils “Vision for the Future” Plan

Feb 19, 26 09:39 AM

The Ohio Railway Museum (ORM), one of the nation’s oldest all-volunteer rail preservation organizations, has laid out an ambitious blueprint aimed at transforming its organization. -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils $38M Expansion

Feb 19, 26 09:24 AM

Western Maryland Railway F7 236 points towards the Mount Clare Roundhouse in Baltimore as part of the B&O Museum. -

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic To Repower Two FPA4s

Feb 19, 26 09:21 AM

A pair of classic, streamlined Alco/MLW FPA4 locomotives that have become signature power on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) are slated for a major mechanical transformation. -

Ohio's Dinner Train Rides At The CVSR

Feb 19, 26 09:18 AM

While the railroad is well known for daytime sightseeing and seasonal events, one of its most memorable offerings is its evening dining program—an experience that blends vintage passenger-car ambience… -

Indiana Dinner Train Rides In Jasper

Feb 19, 26 09:16 AM

In the rolling hills of southern Indiana, the Spirit of Jasper offers one of those rare attractions that feels equal parts throwback and treat-yourself night out: a classic excursion train paired with… -

New Hampshire Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:12 AM

The state's murder mystery trains stand out as a captivating blend of theatrical drama, exquisite dining, and scenic rail travel. -

New York Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:07 AM

New York State, renowned for its vibrant cities and verdant countryside, offers a plethora of activities for locals and tourists alike, including murder mystery train rides! -

UP, NS Set April 30 Date To Refile Merger Application

Feb 18, 26 04:36 PM

Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern have told federal regulators they will submit a revised merger application on April 30, restarting the formal review process for what would become one of the most co… -

CTDOT May Swap Shore Line East’s Electrics For Diesels

Feb 18, 26 04:20 PM

Connecticut’s Shore Line East (SLE) commuter rail service—one of the state’s most scenic and strategically important passenger corridors—could soon see a major operational change. -

NPS Awards $1.93M To Sioux City Railroad Museum

Feb 18, 26 01:21 PM

The Sioux City Railroad Museum has received a $1.93 million National Park Service grant aimed at pushing the museum’s long recovery from the June 2024 flooding. -

$1.3M Mott Foundation Grant To Help Rebuild Rio Grande 2-8-2 No. 464

Feb 18, 26 09:43 AM

A $1.3 million grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation will fund critical work on steam locomotive No. 464, the railroad’s 1903-built 2-8-2 “Mikado” that has been out of service awaiting heavy… -

NS Unveils Third “Landmark Series” Locomotive

Feb 18, 26 09:38 AM

Norfolk Southern has officially introduced ES44AC No. 8184, the third locomotive in its new “Landmark Series,” a program that spotlights the historic rail cities and communities that helped shape both… -

WMSR's Georges Creek Division: Reviving A Long-Dormant Line

Feb 18, 26 09:34 AM

In 2024 the WMSR announced it was rebuilding part of the old WM. The Georges Creek Division will provide both heritage passenger service and future freight potential in a region once defined by coal… -

Chesapeake & Ohio 614 Restoration Pushes Forward

Feb 18, 26 09:32 AM

One of the most recognizable mainline steam locomotives to survive the post–steam era, C&O 614, is steadily moving through an intensive return-to-service overhaul. -

Montana Dinner Train Rides Near Lewistown

Feb 18, 26 09:30 AM

The Charlie Russell Chew Choo turns an ordinary rail trip into an evening event: scenery, storytelling, live entertainment, and a hearty dinner served as the train rumbles across trestles and into a t… -

Wisconsin Dinner Train Rides In North Freedom

Feb 18, 26 09:18 AM

Featured here is a practical guide to Mid-Continent’s dining train concept—what the experience is like, the kinds of menus the museum has offered, and what to expect when you book. -

Pennsylvania Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:09 AM

Pennsylvania, steeped in history and industrial heritage, offers a prime setting for a unique blend of dining and drama: the murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Jersey Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:06 AM

There are currently no murder mystery dinner trains available in New Jersey although until 2023 the Cape May Seashore Lines offered this event. Perhaps they will again soon! -

Huckleberry Railroad: Riding Narrow-Gauge Steam In Michigan!

Feb 18, 26 09:03 AM

The Huckleberry Railroad is a tourist attraction that is part of the Crossroads Village & Huckleberry Railroad Park located in Flint, Michigan featuring several operating steam locomotives. -

New York & Lake Erie Unveils M636 No. 636 In New Colors (2025)

Feb 17, 26 02:05 PM

In mid-May 2025, railfans along the former Erie rails in Western New York were treated to a sight that feels increasingly rare in North American railroading: a big M636 in new paint. -

First Siemens “Northlander” Trainset Arrives In Ontario

Feb 17, 26 11:46 AM

Ontario’s long-awaited return of the Northlander passenger train took a major step forward this winter with the arrival of the first brand-new Siemens-built trainset in the province. -

Sound Transit Set to Launch Cross-Lake Service

Feb 17, 26 10:09 AM

For the first time in the region’s modern transit era, Sound Transit light rail trains will soon carry passengers directly across Lake Washington -

Michigan’s Old Road Dinner Train Still Seeks New Home

Feb 17, 26 10:04 AM

In May, 2025 it was announced that Michigan's Old Road Dinner Train was seeking a new home to continue operations. As of this writing that search continues. -

WMSR Acquires Conemaugh & Black Lick SW7 No. 111

Feb 17, 26 10:00 AM

In a notable late-summer preservation move, the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) announced in August 2025 that it had acquired former Conemaugh & Black Lick Railroad (C&BL) EMD SW7 No. 111. -

MBTA Unveils New Haven-Inspired Locomotive

Feb 17, 26 09:58 AM

he Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority has pulled back the curtain on its newest heritage locomotive, F40PH-3C No. 1071, wearing a bold, New Haven–inspired paint scheme that pays tribute to the… -

Missouri Dinner Train Rides In Branson

Feb 17, 26 09:53 AM

Nestled in the heart of the Ozarks, the Branson Scenic Railway offers one of the most distinctive rail experiences in the Midwest—pairing classic passenger railroading with sweeping mountain scenery a… -

Texas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:49 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:48 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

RTA To Become The Northern Illinois Transit Authority

Feb 16, 26 12:49 PM

Later this year, the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)—the umbrella agency that plans and funds public transportation across the Chicago region—will be reorganized into a new entity: the Norther… -

CPKC Holiday Train Sets New Record In 2025

Feb 16, 26 11:06 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City’s (CPKC) beloved Holiday Train wrapped up its 2025 tour with a milestone that underscores just how powerful a community tradition can become. -

Historic Izaak Walton Inn Slated To Close

Feb 16, 26 10:51 AM

A storied rail-side landmark in northwest Montana—the Izaak Walton Inn in Essex—appears headed for an abrupt shutdown, with employees reportedly told their work will end “on or about March 6, 2026.” -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils Restored American Freedom Train No. 1

Feb 16, 26 10:31 AM

The B&O Railroad Museum has completed a comprehensive cosmetic restoration of American Freedom Train No. 1, the patriotic 4-8-4 steam locomotive that helped pull the famed American Freedom Train durin… -

Union Pacific, Wabtec Ink $1.2B Deal To Modernize AC4400 Fleet

Feb 16, 26 10:25 AM

Union Pacific has signed a $1.2 billion agreement with Wabtec to modernize a significant portion of its GE AC4400 fleet, doubling down on the strategy of rebuilding proven high-horsepower road units r… -

CSX Taps Wabtec For $670M Locomotive And Digital Upgrade

Feb 16, 26 10:19 AM

CSX Transportation says it is moving to refresh and standardize a major piece of its operating fleet, announcing a $670 million agreement with Wabtec. -

New Mexico "Dinner" Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 10:15 AM

If your heart is set on clinking glasses while the desert glows at sunset, you can absolutely do that here—just know which operator offers what, and plan accordingly. -

West Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Elkins

Feb 16, 26 10:13 AM

The D&GV offers the kind of rail experience that feels purpose-built for railfans and casual travelers. -

Indiana Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 10:11 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 09:52 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

West Side Lumber Shay No. 12 Heads Home

Feb 16, 26 09:48 AM

A century-old survivor of Sierra Nevada logging railroading is returning west, recently acquired by the Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine Railroad. -

Building A T1 Again: The PRR 5550 Project

Feb 15, 26 06:10 PM

Today, a nonprofit group, the PRR T1 Steam Locomotive Trust, is doing something that would have sounded impossible for decades: building a brand-new T1 from the ground up. -

PRR T1 No. 5550’s Cylinders Nearing Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:53 PM

According to a project update circulated late last year, fabrication work on 5550’s cylinders has advanced to the point where they are now “nearing completion,” with the Trust reporting cylinder work… -

Santa Fe 3415's Rebuild Nears Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:14 PM

One of the Midwest’s most recognizable operating steam locomotives is edging closer to the day it can lead excursions again. -

Ohio Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:59 AM

Among Lebanon Mason & Monroe Railroad's easiest “yes” experiences for families is the Family Pizza Train—a relaxed, 90-minute ride where dinner is served right at your seat, with the countryside slidi… -

Wisconsin Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:57 AM

Among Wisconsin Great Northern's lineup, one trip stands out as a simple, crowd-pleasing “starter” ride for kids and first-timers: the Family Pizza Train—two hours of Northwoods views, a stop on a tal… -

Illinois "Pizza" Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:55 AM

For both residents and visitors looking to indulge in pizza while enjoying the state's picturesque landscapes, the concept of pizza train rides offers a uniquely delightful experience. -

Tennessee's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:50 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:48 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Staunton!

Feb 15, 26 10:46 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a classic scenic train ride with a genuinely satisfying meal—served at your table while the countryside rolls by—the Virginia Scenic Railway was built for you. -

New Hampshire's Dinner Train Rides In N. Conway

Feb 15, 26 10:45 AM

Tucked into the heart of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Valley, the Conway Scenic Railroad is one of New England’s most beloved heritage railways.