Cascade Tunnel (Washington): Map, Avalanche, Ventilation

Last revised: August 24, 2024

By: Adam Burns

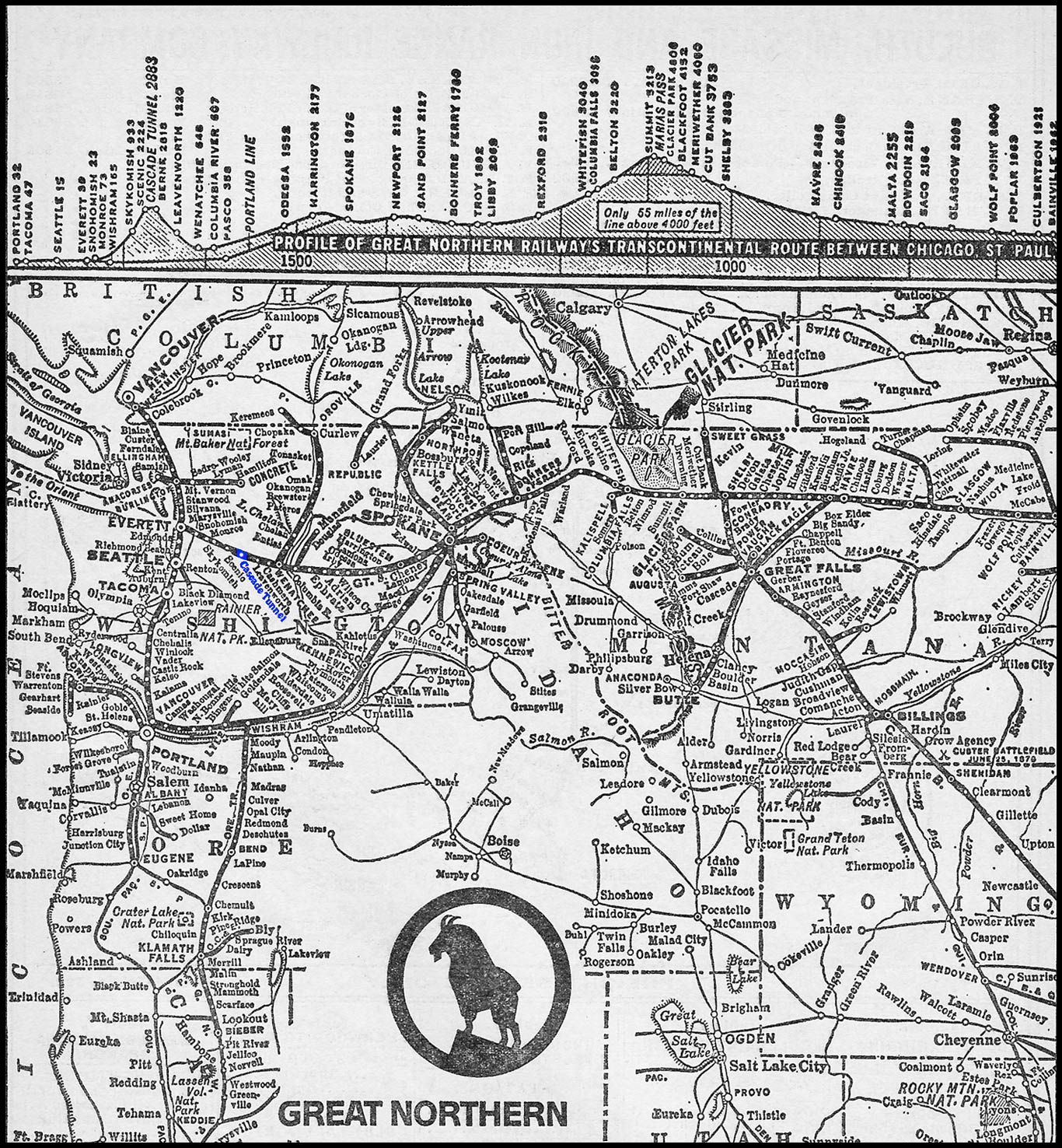

The Great Northern Railway, an esteemed titan in the North American rail transportation industry, was the proud owner of the Cascade Tunnel.

Known for their significant contribution to expanding the railway grid across northwestern U.S., the railway company's inception of the tunnel underpinned its commitment to innovation and progressivism.

Cascade Tunnel, also known as the Stevens Pass Tunnel, is actually the second structure to be built through the mountain, replacing the original in the late 1920s.

At nearly eight miles in length it is one of the longest railroad tunnel ever built and remains in operation today by successor BNSF Railway as part of its transcontinental main line connecting Seattle and Chicago.

For roughly 25 years the tunnel was electrified by GN but this was discontinued in the mid-1950s when conventional diesels took over.

Due to the tunnel's length it has a rather problematic handicap, even today, of requiring ventilation of the shaft for up to 45 minutes.

As a result, Cascade is somewhat of a bottleneck on the BNSF system. Of all the railroads James Hill either owned or controlled in some way, the Great Northern Railway is by far his greatest masterpiece earning him the legendary nickname, Empire Builder.

Photos

History

Nestled within the mountains of Washington state, the Cascade Tunnel stands as an engineering marvel that revolutionized railway transport for the Great Northern Railway.

Construction of this momentous project began on January 12, 1925, a venture inspired by the need for a lower elevation, safer, and more efficient railway route through the treacherous Cascade Mountains.

At A Glance

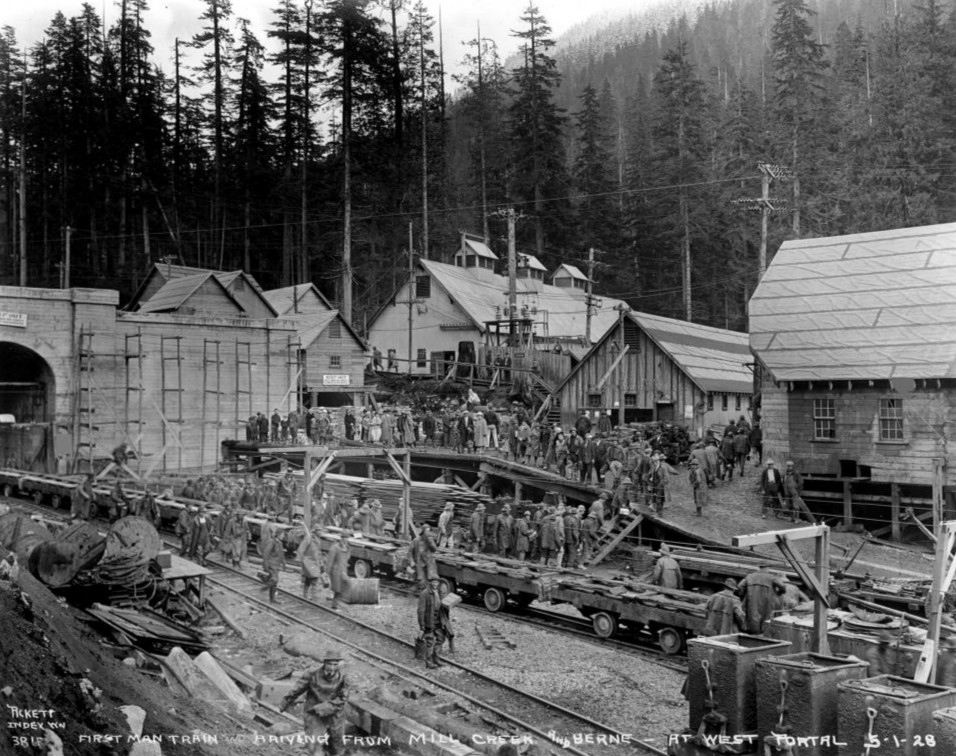

After four years of arduous labor under challenging mountain terrain, the tunnel officially opened on January 12, 1929. This milestone marked a significant advancement in the railway industry, providing safer and more efficient transit for goods and passengers alike.

Astoundingly, the construction of the Cascade Tunnel was a costly endeavor — the total expenditure amounting to a staggering $25.6 million.

Given the inflation rates and economic contexts of the 1920s, this represented a monumental investment, indicative of the tunnel's importance and anticipated potential.

The total cost for both the construction and ongoing maintenance of the Cascade Tunnel was significant. Coupled with the $25 million construction cost were untold millions spent over decades on its upkeep, making it one of the most expensive railway projects of its time.

Original Tunnel

The original tunnel began construction in the late summer of 1897 and took more than three years to complete; the bore opened just prior to the Christmas of 1900. Only July 10, 1909 GN further improved the tunnel by completing a short, 6,600-volt 25 Hz three-phase AC electrification system to eliminate asphyxiation issues caused by steam locomotives.

While the original tunnel still sat at a very high elevation of nearly 3,383 feet it eliminated a hellish grouping of switchbacks required to scale Stevens Pass, totaling more than eight miles in length.

This setup was not only a major issue due to the steep grades but also unrelenting snowfalls could bury trains for days.

During one such incident in 1910 an avalanche toppled a passenger train waiting to be dug out, killing nearly 100 souls. The accident is chronicled in Martin Burwash's book Vis Major listed below.

While the original 2.6-mile long tunnel improved railroad operations by reducing grades to between 1.7% and 2.2%, it still sat high on the mountain within range of punishing Cascade blizzards.

Following the avalanche disaster at Wellington, Washington the GN was forced to find a better route over the

mountain.

In 1925 the railroad began construction on a new Cascade Tunnel, located about 500 feet down the mountainside. For the most part this tunnel sat away from the worst of the mountain's winters being located below the highest elevations.

The tunnel is situated in the beautiful county of King, Washington state. The western portal is near the unincorporated community of Scenic, while the eastern portal located near Berne, at the base of Stevens Pass in the Cascade Mountain range.

Testifying to its engineering prowess, Cascade is an impressive 7.8 miles long, making it the longest railway tunnel in the United States. In its time, it was also the longest tunnel of its kind in the world, announcing America's standing in the realm of railway engineering.

The ruling grade is a manageable 1.7 percent. This relatively gradual grade permits trains to traverse through the mountainous terrain effortlessly, ensuring safe and efficient cargo and passenger transportation.

Location

Electrification

The extraordinary length forced the Great Northern to electrify the tunnel to avoid fumigation issues, caused by operating steam locomotives. Prior to the new bore's completion, GN updated its electrification to a modern, 11,000-volt, 25 Hz AC monophase system.

It was finished in 1928 and ran a length of 73 miles between Skykomish and Wenatchee. Electrification was provided by Puget Sound Power and Light Company, which constructed new power plants at Wenatchee and Skykomish that supplied 7,500 kilowatts of power to the railroad.

In addition, GN built new shops at the Appleyard Terminal in South Wenatchee to maintain its fleet of electrics. The electrification continued until January, 1956 when the system was shutdown in favor of diesels.

Today, Cascade is equipped with a unique ventilation system to manage the hazardous exhaust fumes from diesel locomotives. Originally relying on natural drafts, the tunnel now employs powerful fans at the eastern end, which operate between trains to expel exhaust and draw in fresh air, maintaining the tunnel's air quality.

Great Northern 1-C+C-1 #5011 (Class Y-1) was already retired when photographed here by Stan Kistler at Wenatchee, Washington on July 5, 1957. The 3,000 horsepower unit was originally completed as a boxcab by General Electric/Alco in 1927. It was involved in a derailment during World War II while leading the "Fast Mail" and completely destroyed. GN shop forces managed to salvage the running gear and frame and rebuilt the unit using FT cab ends acquired from Electro-Motive. After retirement she was acquired by the Pennsylvania Railroad as a parts source for the other Class Y's the PRR had purchased for use in freight service between Philadelphia - Enola - Baltimore. Author's collection.

Great Northern 1-C+C-1 #5011 (Class Y-1) was already retired when photographed here by Stan Kistler at Wenatchee, Washington on July 5, 1957. The 3,000 horsepower unit was originally completed as a boxcab by General Electric/Alco in 1927. It was involved in a derailment during World War II while leading the "Fast Mail" and completely destroyed. GN shop forces managed to salvage the running gear and frame and rebuilt the unit using FT cab ends acquired from Electro-Motive. After retirement she was acquired by the Pennsylvania Railroad as a parts source for the other Class Y's the PRR had purchased for use in freight service between Philadelphia - Enola - Baltimore. Author's collection.Interestingly, this ventilation system proved to be more difficult to operate than originally expected; fumigation problems haunted the railroad and

its successor, Burlington Northern, not only because of the tunnel's

length but also due to the grade, about 1.7% from west to east.

The first ventilation systems took up to, if not more than, an hour to clear the tunnel of fumes before another train was allowed to enter. Additionally, crews were required to wear, or at least with them, respirators in the event of a ventilation failure as it usually took a train a full hour to scale the tunnel.

Great Northern B-D+D-B electric #5019 (Class W-1) is seen here between assignments at Skykomish, Washington on June 9, 1956. Capable of producing 5,000 continuous horsepower (6,000 starting) the big electric (and sister #5018), built by Alco/General Electric in 1947, saw less than ten years of service before GN turned off the electricity through 7.8-mile Cascade Tunnel in August, 1956. Stan Kistler photo. Author's collection.

Great Northern B-D+D-B electric #5019 (Class W-1) is seen here between assignments at Skykomish, Washington on June 9, 1956. Capable of producing 5,000 continuous horsepower (6,000 starting) the big electric (and sister #5018), built by Alco/General Electric in 1947, saw less than ten years of service before GN turned off the electricity through 7.8-mile Cascade Tunnel in August, 1956. Stan Kistler photo. Author's collection.Today

Today, owner BNSF Railway has installed a ventilation system capable of removing exhaust within 20 minutes although crews are still required to have respirators with them at all times.

For an idea of just how bad it could be for crewmen operating through tunnel please read this account by John Crosby who worked this segment of the line during the Burlington Northern era.

Train speeds today for BNSF freights and Amtrak passenger trains are held to 25 mph. One still has to wonder, however, why Burlington Northern did not exercise its ownership of nearby Snoqualmie Tunnel after the Milwaukee Road abandoned its main line through this region in 1980.

Using that bore, which was the best engineered tunnel across the Cascade range, would have saved BN and BNSF millions in maintenance costs and liability.

Legacy

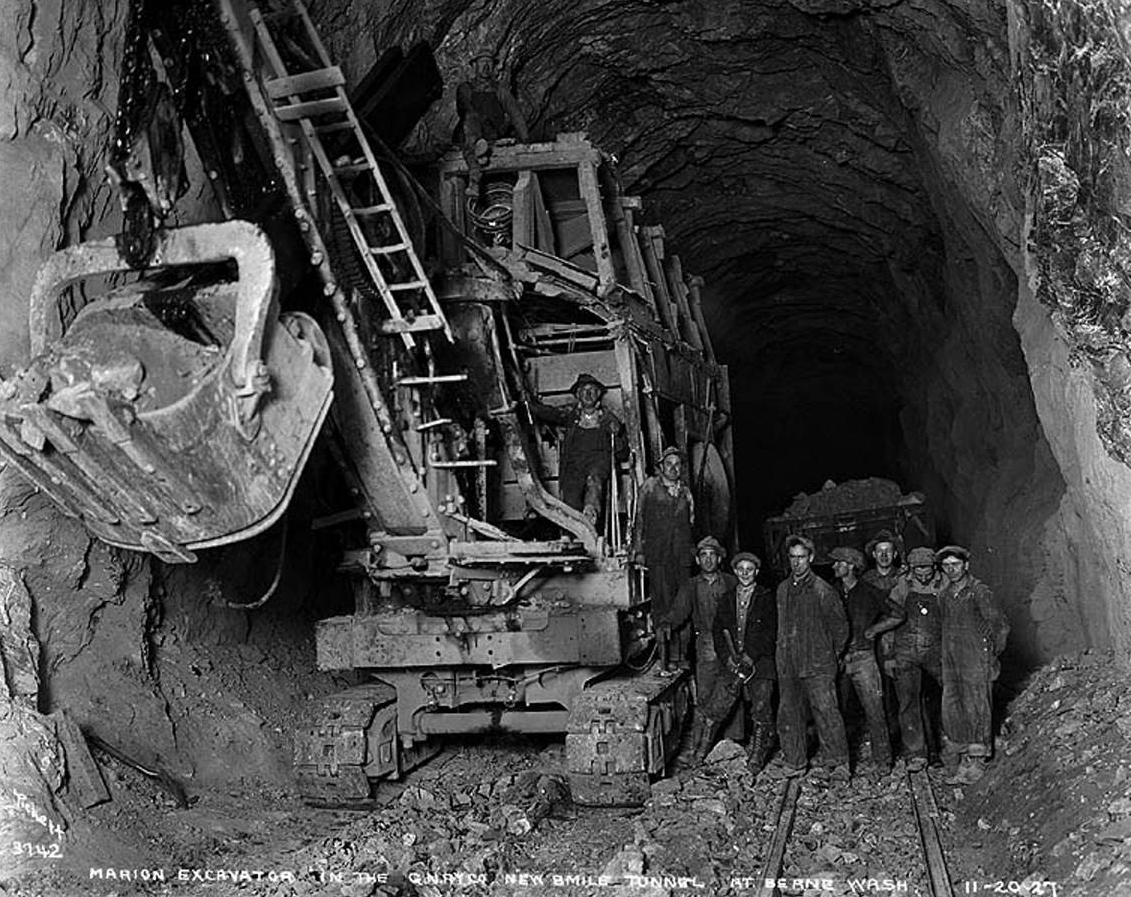

Given its impressive length, constructing the Cascade Tunnel was no ordinary feat. The project demanded advanced engineering techniques, sturdy machinery, and a sizable and dedicated workforce who toiled in difficult conditions to bring this ambitious project to fruition.

The decision to drill a tunnel of this magnitude through the Cascade Mountains was driven by necessity. The Great Northern Railway's existing route over Stevens Pass was perilous, particularly during the harsh winter months when avalanches posed significant threats.

The safer, lower elevation route through the Cascade Tunnel offered a solution, forever changing the way cargo and passengers transited the treacherous Cascade ranges.

Despite its significant initial cost and ongoing maintenance expenses, the Cascade Tunnel proved an excellent investment for the Great Northern Railway, allowing for consistent, year-round operation. It greatly enhanced the railway's efficiency, providing a more reliable route for goods and passenger traffic.

Over the decades, the Cascade Tunnel has undergone numerous upgrades and modifications. The original wooden interior was replaced with concrete lining, electrical systems were updated, and ventilation techniques improved, ensuring the tunnel's functionality in line with evolving railway technologies.

The electrification process employed in the Cascade Tunnel was an ambitious endeavor by the Great Northern Railway. Far ahead of its time, the overhead catenary system powered trains through the tunnel for nearly half a century.

The Cascade Tunnel's operational status today stands as a testament to its enduring robustness and relevance. Despite being nearly a century old, the tunnel continues to operate under the auspices of the BNSF Railway, attesting to its durability and significance.

In its time, the Cascade Tunnel saw various locomotives pass through it. From sturdy steam engines to efficient electric locomotives, and powerful diesel trains, the types of locomotives used reflected the evolution of rail transportation technology.

Today, the Cascade Tunnel remains a vital artery for freight transportation. Amid America's vast railway network, it ensures the smooth and efficient movement of goods over the Cascade Mountains, playing a crucial role in the national supply chain.

The tunnel stands not just as an architectural triumph but also a symbol of human grit, determination, and ingenuity. The many men who worked relentlessly to first conceive, design, and then construct this engineering marvel are a testament to the human spirit's resilience and inventiveness.

As a national asset, Cascade Tunnel showcases America's industrial prowess during the early 20th century. It records the country's epoch marked by significant industrial growth, the propagation of railway networks, and a nationwide commitment towards infrastructural development, progress, and expansion.

For historians and railroad enthusiasts, the Cascade Tunnel offers a wealth of information. It intertwines engineering prowess with human stories of perseverance, painting a comprehensive picture of the challenges and triumphs seen during the era of its construction.

Today, although goods trains constitute the bulk of its traffic, the Cascade Tunnel occasionally services passenger trains as well. It's an integral part of Amtrak's Empire Builder route, an experience that offers passengers a firsthand view of this historic tunnel.

Modern train control technology plays an indispensable role in keeping the Cascade Tunnel operational and efficient. Advanced signal systems, slide detection technologies, and electric door systems ensure the safe transit of trains through this enormous tunnel.

The Cascade Tunnel's climactic inclusion in various works of literature and film underscores its inspirational status and relevance. Its monumental struggle during construction and triumphant landmark status is a compelling narrative that continues to captivate audiences.

While Cascade Tunnel was relinquished of its title as the world's longest railway tunnel many years ago, its legacy has not diminished. It continues to inspire modern engineering feats, and its historical significance in American rail transportation remains unparalleled.

In an era of expanding and improving transportation infrastructures, the story of the Cascade Tunnel provides valuable lessons. It's a testament to the power of innovation, strategic planning, and focused execution, reminding us that challenges are not impediments, but catalysts toward progress.

From its conception, construction, and continuous operation, the Cascade Tunnel embodies a significant chapter in the history of railway transportation. And while it no longer holds the title of the world's longest tunnel, its enduring operation, advanced adaptations, and rich history underline the Cascade Tunnel's prominence on the pages of American railway history.

Sources

- Hidy, Ralph W., Hidy, Muriel E., Scott, Roy V., And Hofsommer, Don L. Great Northern Railway, The: A History. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004 edition.

- Kelly, John. Great Northern Railway: Route Of The Empire Builder. Hudson: Iconografix, 2013.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

Recent Articles

-

Florida "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:53 AM

This article delves into wild west rides throughout Florida, the historical context surrounding them, and their undeniable charm. -

West Virginia "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:49 AM

While D&GV is known for several different excursions across the region, one of the most entertaining rides on its calendar is the Greenbrier Express Wild West Special. -

Alabama "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:47 AM

Although Alabama isn't the traditional setting for Wild West tales, the state provides its own flavor of historic rail adventures that draw enthusiasts year-round. -

Michigan "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:46 AM

While the term "wild west" often conjures up images of dusty plains and expansive deserts, Michigan offers its own unique take on this thrilling period of history. -

Grand Trunk Western 4-6-2 No. 5629

Feb 13, 26 12:10 AM

Included here is a detailed look at 5629’s build date and design, key specifications, revenue career on the Grand Trunk Western, its surprisingly active excursion life under private ownership, and its… -

New York Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:19 PM

New York is home to several Easter-themed train rides including the Adirondack Railroad, Catskill Mountain Railroad, and a few others! -

Missouri Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:13 PM

The beautiful state of Missouri is home to a handful of heritage railroads although only one provides an Easter-themed train ride. Learn more about this event here. -

Arizona's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:05 PM

Let's delve into the captivating world of Arizona's Wild West train adventures, currently offered at the popular Grand Canyon Railway. -

Missouri's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:49 PM

In Missouri, a state rich in history and natural beauty, you can experience the thrill of a bygone era through the scenic and immersive Wild West train rides. -

Maine's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:42 PM

Tea trains aboard the historic WW&F Railway Museum promises to transport you not just through the picturesque landscapes of Maine, but also back to a simpler time. -

Pennsylvania Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:09 PM

In this article, we explore some of the most enchanting tea train rides in Pennsylvania, currently offered at the historic Strasburg Rail Road. -

Nevada St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 11:39 AM

Today, restored segments of the “Queen of the Short Lines” host scenic excursions and special events that blend living history with pure entertainment—none more delightfully suspenseful than the Emera… -

Minnesota Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 10:22 AM

Among MTM’s most family-friendly excursions is a summertime classic: the Dresser Ice Cream Train (often listed as the Osceola/Dresser Ice Cream Train). -

Wisconsin's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:54 PM

Through a unique blend of interactive entertainment and historical reverence, Wisconsin offers a captivating glimpse into the past with its Wild West train rides. -

Georgia's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:44 PM

Nestled within its lush hills and historic towns, the Peach State offers unforgettable train rides that channel the spirit of the Wild West. -

North Carolina's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:36 PM

North Carolina, a state known for its diverse landscapes ranging from serene beaches to majestic mountains, offers a unique blend of history and adventure through its Wild West train rides. -

South Carolina's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:16 PM

There is only location in the Palmetto State offering a true dinner train experience can be found at the South Carolina Railroad Museum. Learn more here. -

Rhode Island's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:08 PM

Despite its small size, Rhode Island is home to one popular dinner train experience where guests can enjoy the breathtaking views of Aquidneck Island. -

New York Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:56 PM

Tea train rides provide not only a picturesque journey through some of New York's most scenic landscapes but also present travelers with a delightful opportunity to indulge in an assortment of teas. -

California Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:37 PM

In California you can enjoy a quiet tea train experience aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train, which offers an afternoon tea service. -

Tennessee Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:19 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Ohio "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:34 AM

For those enamored with tales of the Old West, Ohio's railroad experiences offer a unique blend of history, adventure, and natural beauty. -

New York "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:23 AM

Join us as we explore wild west train rides in New York, bringing history to life and offering a memorable escape to another era. -

New Mexico Murder Mystery Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:12 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails -

New York Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:09 AM

While CMRR runs several seasonal excursions, one of the most family-friendly (and, frankly, joyfully simple) offerings is its Ice Cream Express. -

Michigan Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:02 AM

If you’re looking for a pure slice of autumn in West Michigan, the Coopersville & Marne Railway (C&M) has a themed excursion that fits the season perfectly: the Oktoberfest Express Train. -

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 10:07 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer!