Chicago Great Western Railway: Map, Photos, History, Rosters

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Chicago Great Western Railway was a somewhat obscure Midwestern granger, operating in the shadows of the much larger Chicago & North Western, Burlington, Rock Island, and Milwaukee Road.

It largely kept to itself with a focus towards customer service and modernity to maintain an efficient, profitable business. The 1,500-mile carrier was a David among Goliath's surrounding by roads nearly or over 10,000 route miles in length.

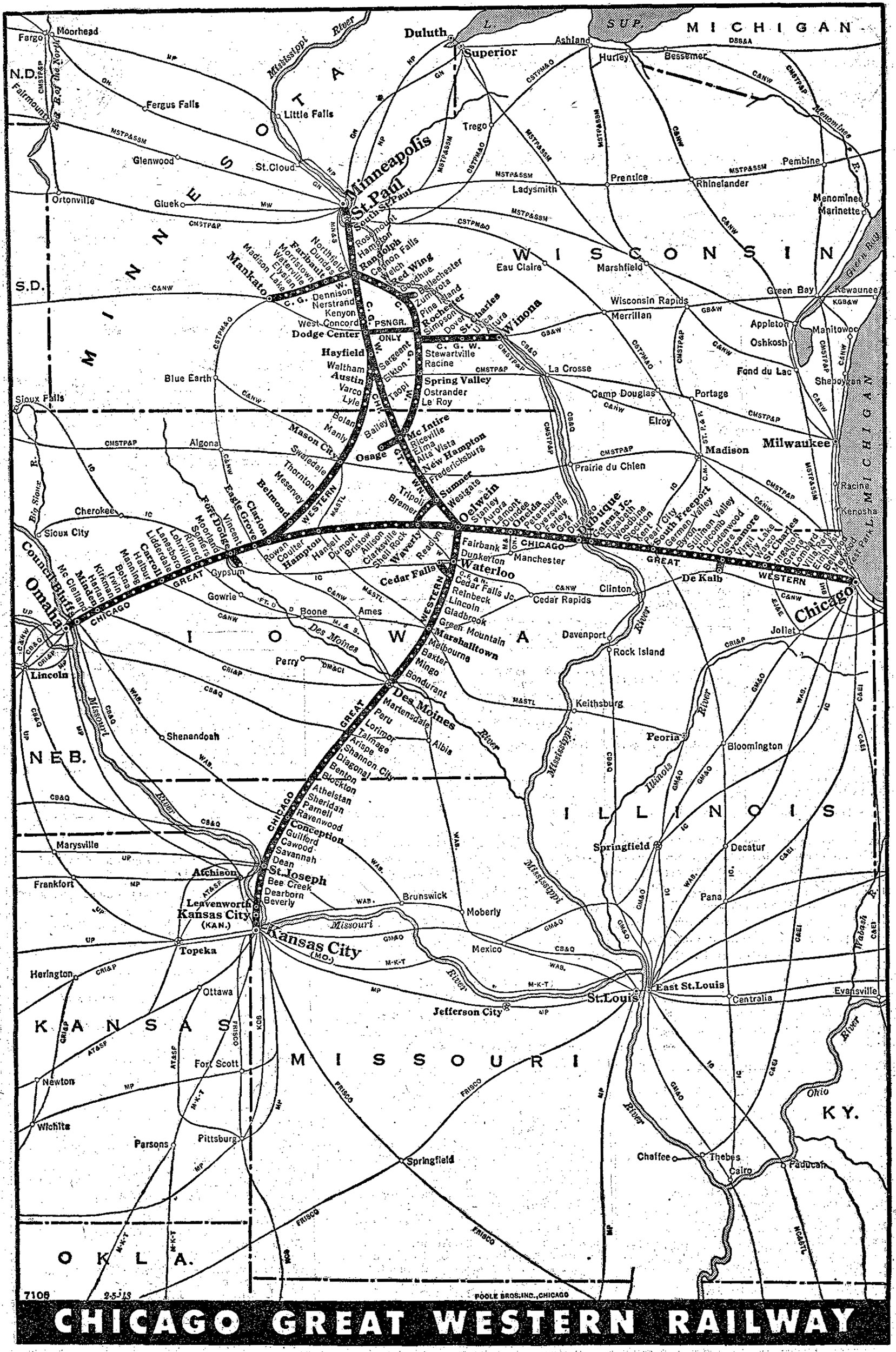

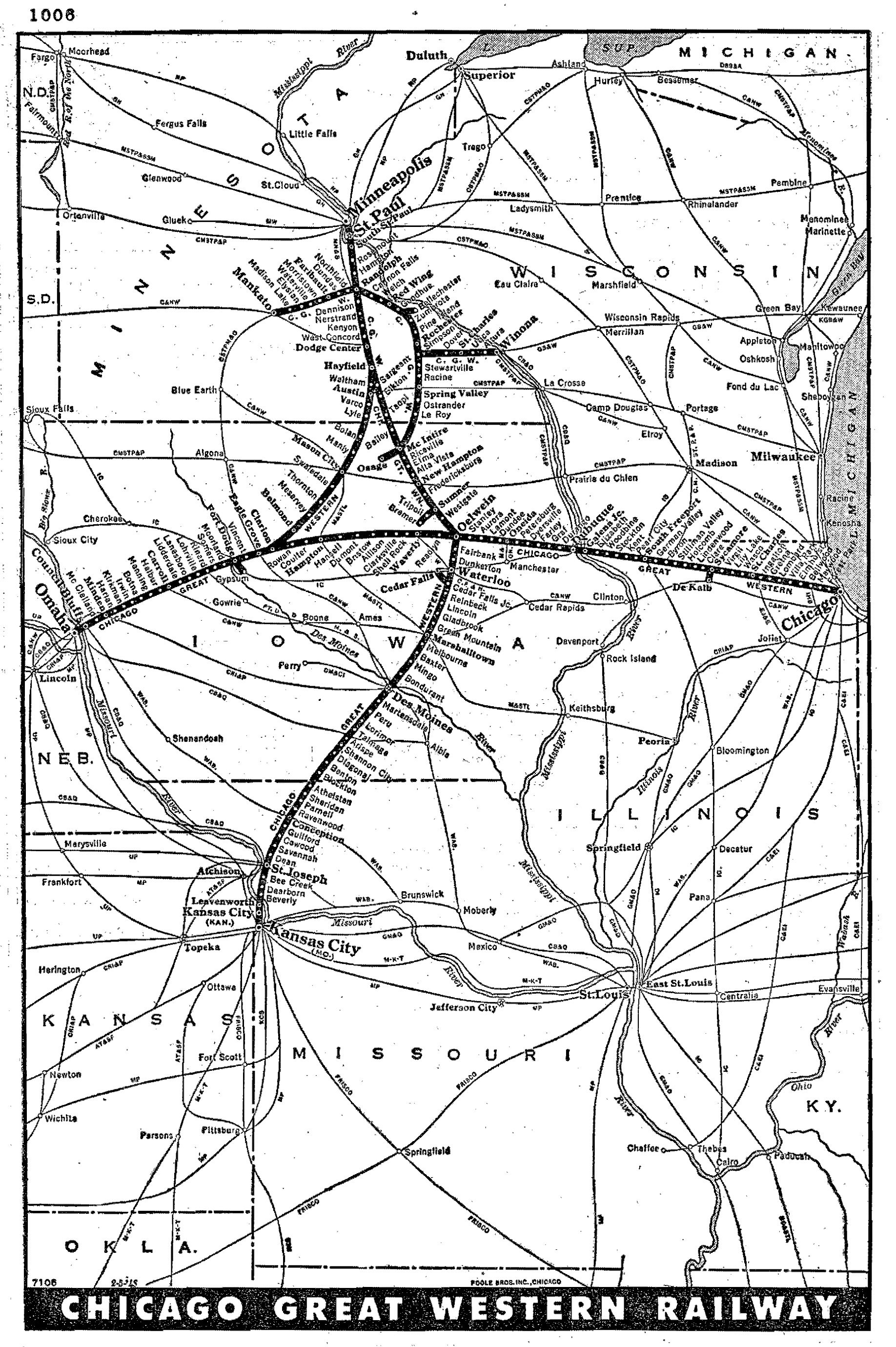

While its system was not large it did reach many notable markets such as Chicago, St. Paul/Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City. What the railroad lacked in size it more than made up for in customer service.

Always the innovator the CGW was constantly looking to reach new customers, streamline operations, cut costs, and generally carry out any measure possible to grow business.

Alas, its small size coupled with stifling federal regulations, rising costs, and competition from other transportation modes eventually brought about its end.

The much larger C&NW, in an effort to reach the Kansas City gateway, purchased the Corn Belt Route in the late 1960's and set about abandoning much of its network.

A manufacturer's photo of new Chicago Great Western covered wagons featuring F7A #156 and an F7B at Electro-Motive's plant in Illinois, circa 1949.

A manufacturer's photo of new Chicago Great Western covered wagons featuring F7A #156 and an F7B at Electro-Motive's plant in Illinois, circa 1949.History

What became one of the great Midwestern railroads would not have happened without the vision and hard work of Alpheus Beede (A.B.) Stickney.

Predecessors

While the Chicago Great Western's immediate heritage begins during the 1880's the company's earliest roots date back to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Air Line Railroad (CStC&MAL) organized in 1850 to link Chicago with the Mississippi River.

There was some grading carried out by this predecessor but ultimately it never secured the financial backing needed to actually begin construction.

There were many such projects launched around this time in an effort to reach Chicago, such as early components of the C&NW, Milwaukee Road, and Burlington.

Hopeful visionaries not only realized the growing importance of this city but also the Midwest's traffic potential in agriculture and natural resources (timber and iron ore to the north, and coal to the south).

With the CStC&MAL project going nowhere the Minnesota & Northwestern Railroad (M&NW) was granted a charter by the Minnesota state legislature on March 4, 1854.

According to historian H. Roger Grant's authoritative book, "The Corn Belt Route: A History Of The Chicago Great Western Railroad Company," the M&NW was to build:

"...from a point on the North West shore of Lake Superior...by St. Anthony and St. Paul...to such a point on the northern boundary of the State of Iowa - as the board of Directors may designate; which shall be selected with reference to the best route to the City of Dubuque."

Chicago Great Western motorcar #1000, built by McKeen in 1910 and later repowered by EMC, is seen here at the end of the Winona Branch in Winona, Minnesota on June 24, 1952. Roger Puta photo.

Chicago Great Western motorcar #1000, built by McKeen in 1910 and later repowered by EMC, is seen here at the end of the Winona Branch in Winona, Minnesota on June 24, 1952. Roger Puta photo.A.B. Stickney

This project also ran into trouble although it may have experienced greater success had it not been for the financial Panic of 1857. As with the CStC&MAL nothing more happened with the M&NW project until A.B. Stickney got involved.

Along with business partner and investor William Marshall the two purchased the company's 10,000 shares outstanding believing it could be turned into a successful operation.

Logos

By then, Stickney was no stranger to the railroad industry. He was born in Maine on June 17, 1840 and became interested in the railroad industry after the Civil War.

The energetic and sharp young man worked his way up through ranks with several different railroads; he helped build predecessors of the Chicago & North Western and then went to work for James J. Hill's, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway (early component of the Empire Builder's later Great Northern Railway).

He later found top positions at Canadian Pacific and another Midwestern granger, the Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway ("The Peoria Gateway"), before going off on his own with the Minnesota & Northwestern.

Chicago Great Western F3A #150 has arrived at the railroad's small depot in Council Bluffs, Iowa (situated near South 3rd Street and 16th Avenue) with train #13, the overnight run from Minneapolis, circa 1957. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago Great Western F3A #150 has arrived at the railroad's small depot in Council Bluffs, Iowa (situated near South 3rd Street and 16th Avenue) with train #13, the overnight run from Minneapolis, circa 1957. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

Now heading his own company, Stickney's project quickly took off as he began track surveys for a 110-mile line from St. Paul to Mona, Iowa where a connection would be established with the Cedar Falls & Minnesota (leased by the Illinois Central).

Actual construction of the route began in 1884 and was officially ready for service on September 27, 1885. Having a great deal of experience in both managing and building railroads, particularly within the hotly contested Midwestern market, Stickney realized for his venture to sustain long term success it must link the largest cities.

There was none larger, of course, than Chicago and he quickly made reaching America's railroad capital a top priority.

During May of 1885, Stickney acquired the assets of the Dubuque & Northwestern Railroad (D&NW) for this purpose, a system originally incorporated on June 20, 1883 as a narrow-gauge to connect Dubuque with an unspecified northwesterly point ("...to run in a northwestern direction into Minnesota and Dakota and connect with the Northern Pacific...").

Before any construction could take place the road encountered financial troubles which allowed Stickney to become involved.

Chicago Great Western F7A #155 departs St. Paul, Minnesota during the early 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago Great Western F7A #155 departs St. Paul, Minnesota during the early 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.It would build a 50-mile line west from Dubuque to reach Compton (near Lamont). From there, another new segment would branch from the existing M&NW at Hayfield and run in a southeasterly direction. The D&NW began construction on July 29, 1885 with the first eight miles opening to Durango by year's end.

Into 1886 work quickened while at the same time the M&NW began construction of its section. On October 20, 1886 a through route from Dubuque, along the Mississippi River, to St. Paul was completed and ready for service.

The 253-mile pike was still a relatively small operation in comparison to the surrounding Chicago & North Western, Rock Island, Burlington, and Milwaukee Road.

However, considering the relatively late time period in which he began it is rather incredible Stickney accomplished what he did.

This is because that while the 1880's witnessed more trackage laid across the country than during any other decade, the big grangers mentioned above used a great deal of resources to keep out potential new threats.

At A Glance

1,495.27 (1930) 1,458 (1950) | |

Chicago - Oelwein, Iowa - Minneapolis Oelwein - Des Moines, Iowa - Kansas City Oelwein - Clarion, Iowa Minneapolis - Mason City, Iowa - Fort Dodge, Iowa - Omaha, Nebraska Randolph, Minnesota - Mankato Randolph - Red Wing - Rochester, Minnesota - McIntire, Iowa Rochester - Winona | |

Freight Cars: 4,490 Passenger Cars: 33 | |

While the D&NW/M&NW projects were under way Stickney established a new system, the Minnesota & Northwestern Railroad Company of Illinois.

It was officially incorporated on February 25, 1886 and would build a direct link into Chicago via Dubuque. Once again he wasted little time as construction commenced that same July.

The line would not actually reach downtown Chicago but the nearby suburb of Forest Home (Forest Park) and then utilize trackage rights over what later became the Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal (B&OCT).

By February of 1887 the 97-mile line from Forest Home to South Freeport was finished although regular service did not commence until later that summer.

Part of the route, which included 27 miles from Forest Home to St. Charles, utilized the grading work of the moribund Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Air Line previously mentioned.

To reach home rails into Dubuque, trackage rights were initially secured over the Illinois Central before construction of this final extension began in March of 1887. After only a year the 50-mile line was completed in early 1888 and opened for service on February 9th.

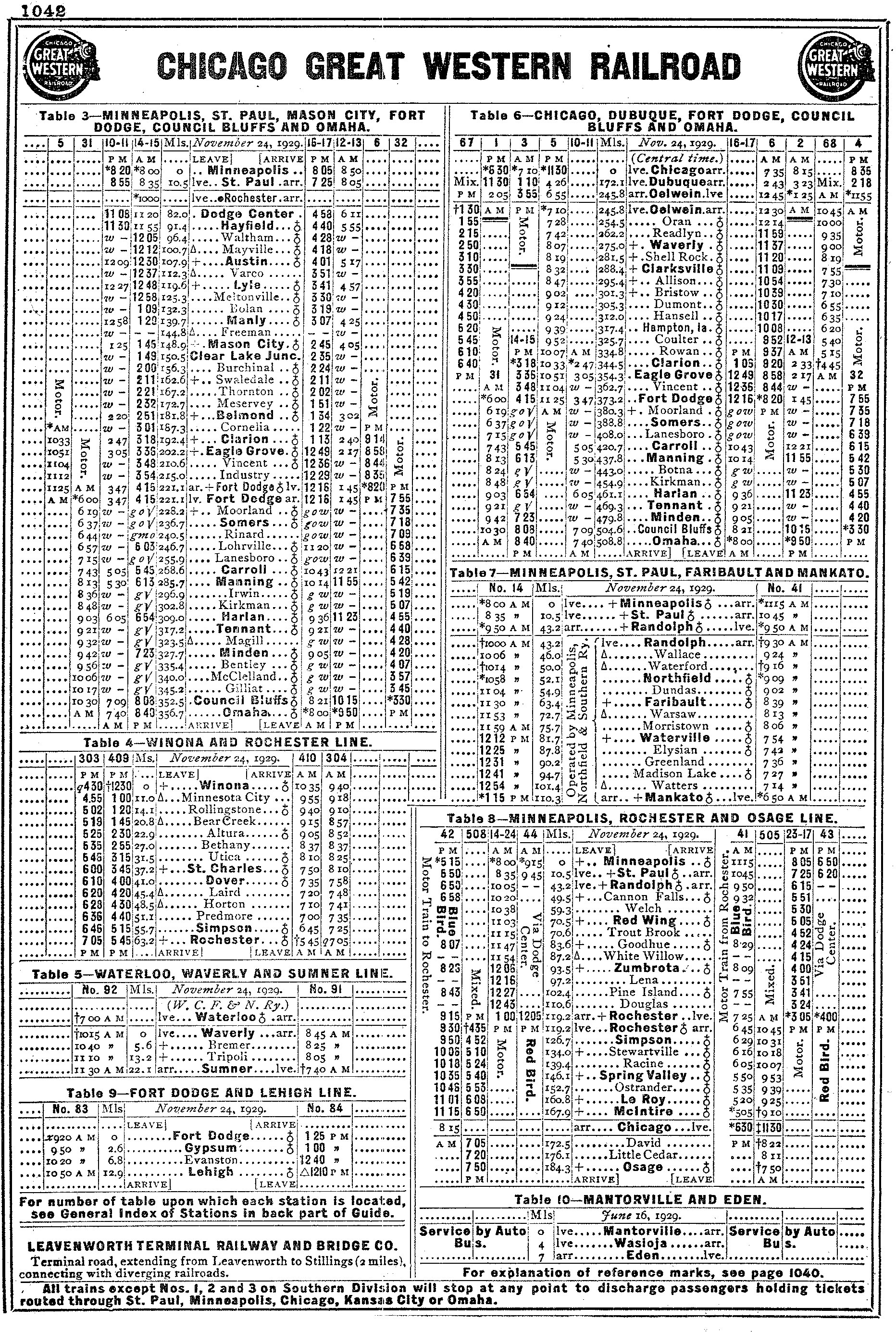

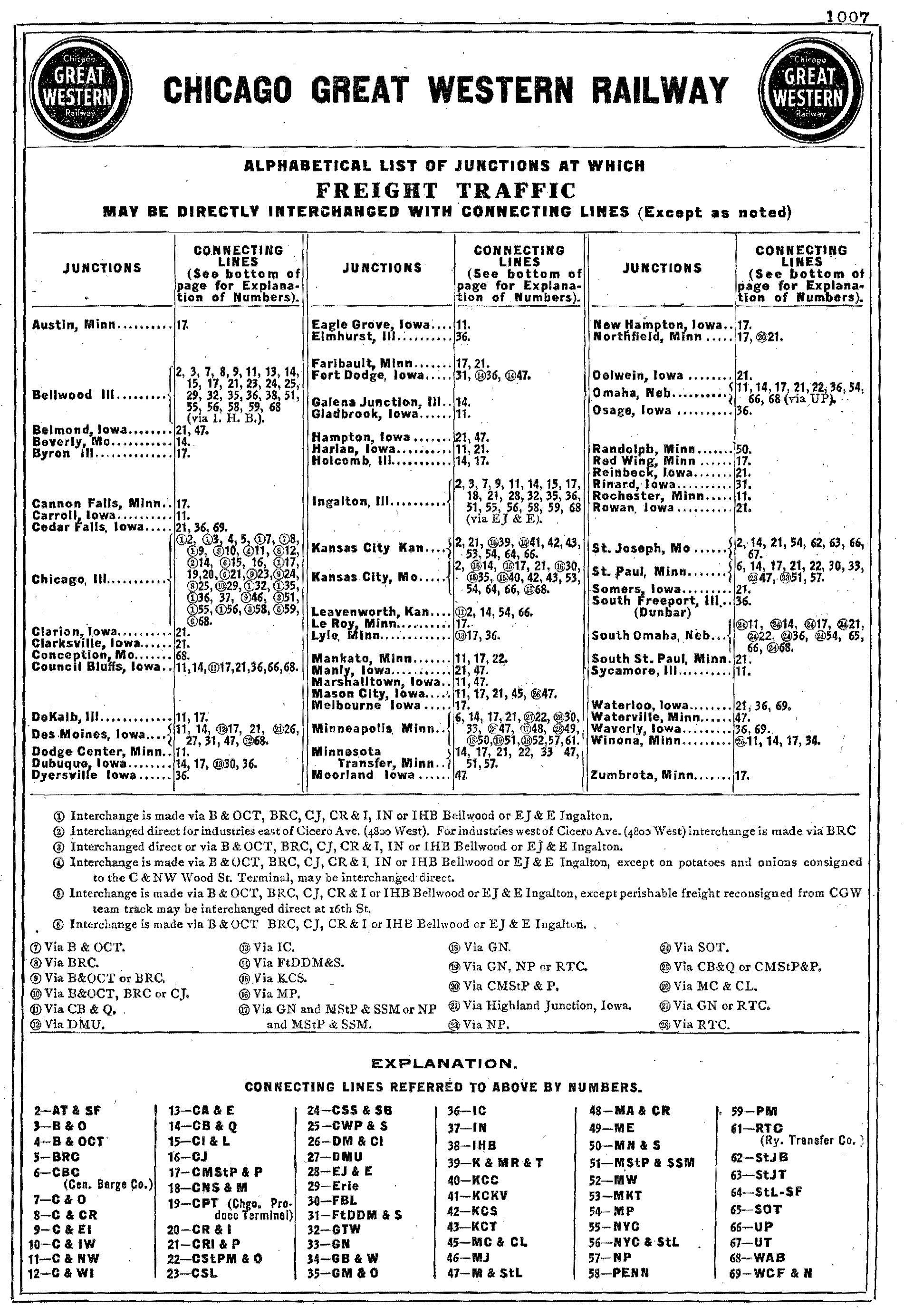

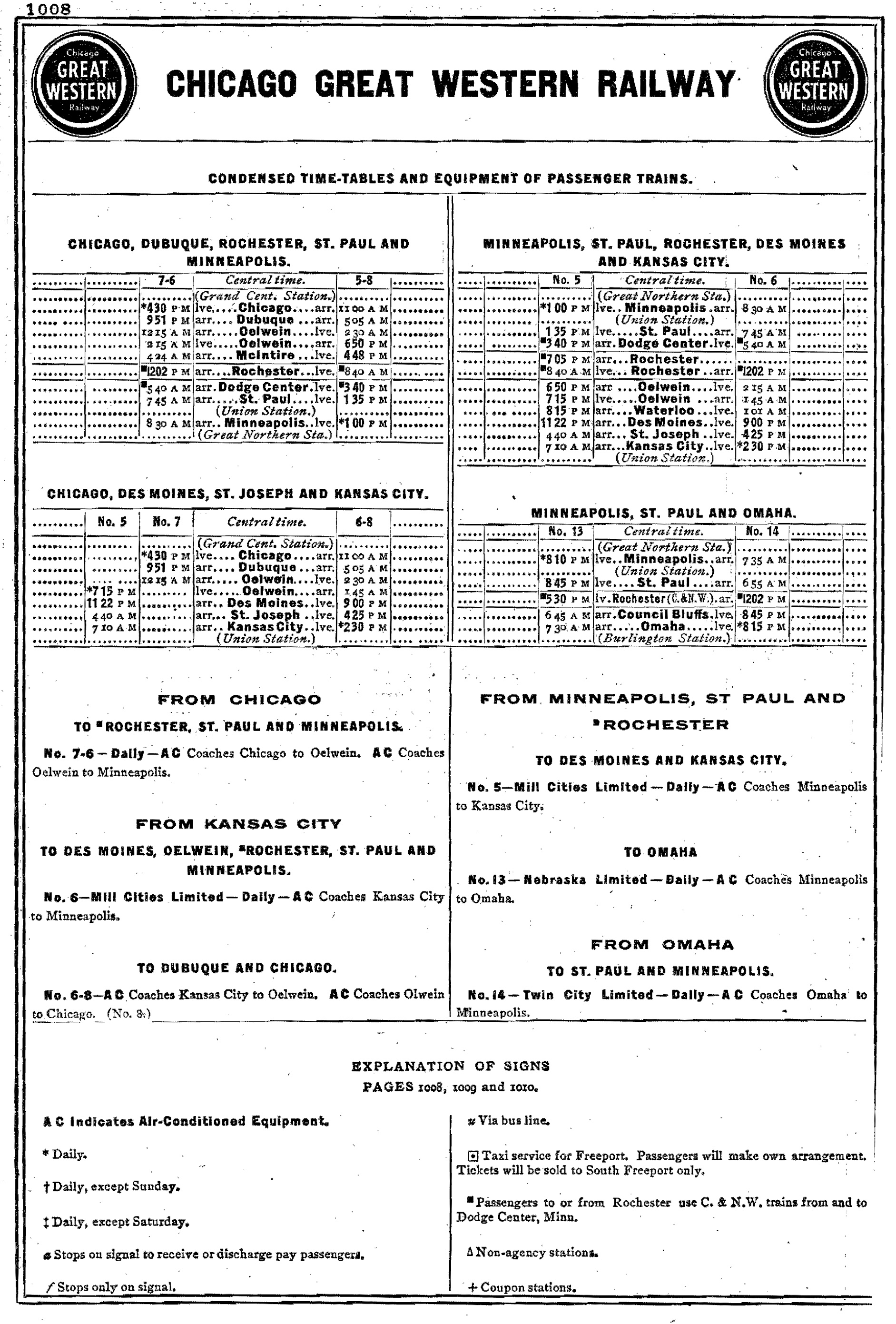

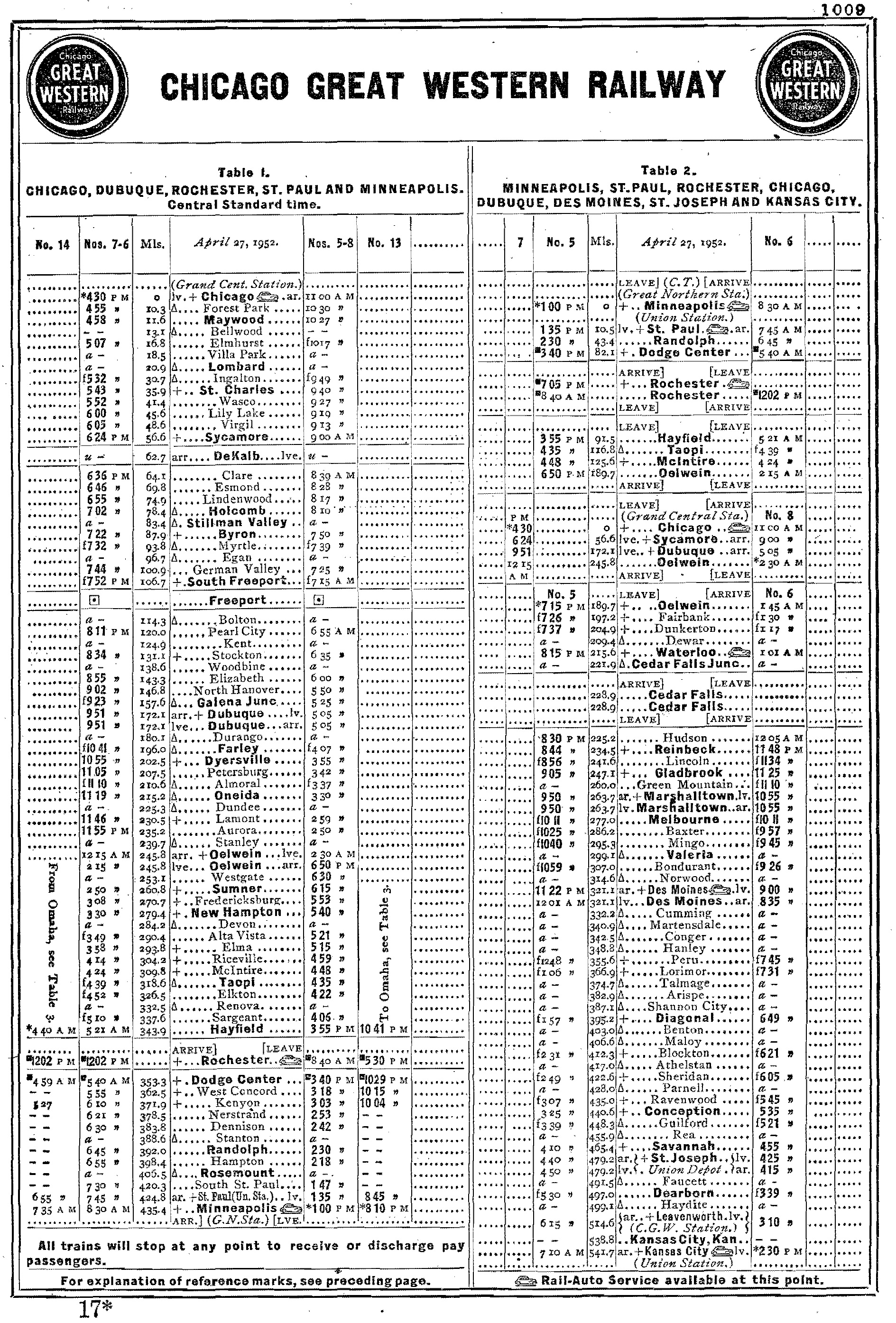

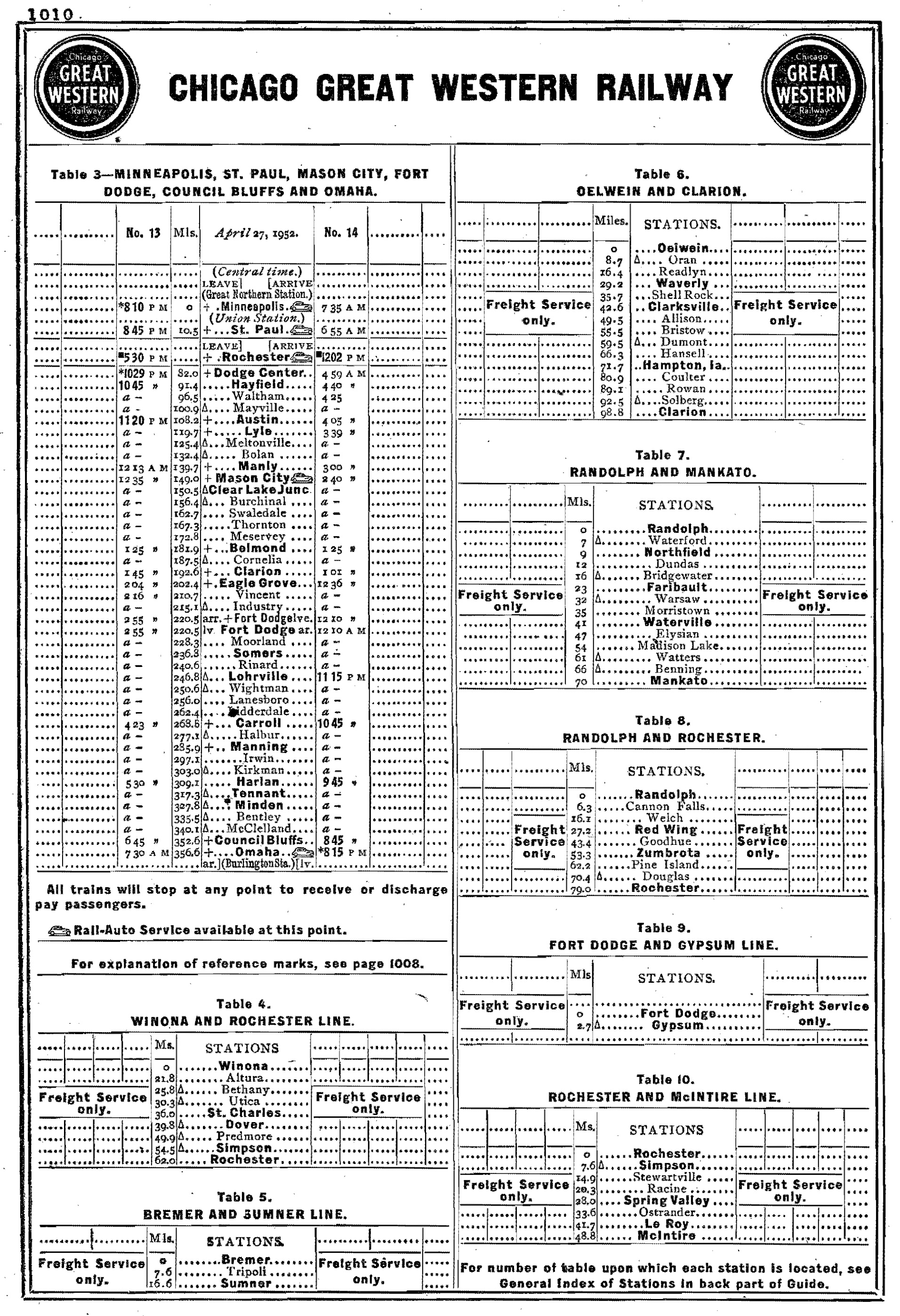

Timetables (1930)

The Chicago main line contained one notable infrastructure project, the 2,493-foot Winston Tunnel. It proved an expensive and contentious operational problem throughout its history.

The bore was completed in early 1888 but the unstable blue clay through which it was built required extensive maintenance over the years and major rebuilds at various times.

As the route was being finished three significant events occurred during 1887: first, Stickney acquired the small Dubuque & Dakota on January 19th which branched from the M&NW at Sumner, reached Waverly, and extended as far west as Hampton; later that year he added the Wisconsin, Iowa & Nebraska, which had opened a section of track from Waterloo to Des Moines, Iowa (as well as a branch to Cedar Falls).

He connected it to Oelwein and then pushed southward into Kansas City reaching as far as St. Joseph in May of 1888.

From there, a new company was chartered, the Leavenworth & St. Joseph which was completed to Beverly along the east bank of the Missouri River in December of 1890.

To reach Kansas City directly, trackage rights were carried out over the Rock Island, Union Pacific, and Kansas City, Wyandotte & Northwestern (Missouri Pacific).

Finally, while all of this was ongoing his entire enterprise was renamed the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad in December of 1887 to better reflect the company's future intentions.

Chicago Great Western freights meet at Poplar Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois in May, 1960. Rick Burn photo.

Chicago Great Western freights meet at Poplar Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois in May, 1960. Rick Burn photo.Creation

As Stickney eyed a westward extension towards the important western gateway of Omaha, where interchange could be established with the transcontinental Union Pacific, his railroad ran into financial issues and entered receivership on January 16, 1892.

The bankruptcy was short-lived, however, and assets of the CStP&KC were acquired (initially via lease, the CStP&KC was later dissolved in 1893) by the newly formed Chicago Great Western Railway on July 1st of that same year with Stickney remaining in control.

Interestingly, while the company weathered the crippling financial Panic of 1893 the troubled economic conditions warranted no further expansion at that time.

One notable event which took place was moving the primary shops from South St. Paul to Oelwein, Iowa. This town was situated exactly in the center of the Great Western system, making it an ideal location for such facilities.

The Oelwein Shops opened in April of 1899 containing locomotive and car repair shops, back shops, store house, and other buildings related to maintaining the company's equipment and infrastructure. They were expanded a few years later when a large 40-stall roundhouse opened in 1904.

Recently delivered Chicago Great Western GP30's, including #201 and #202 closest to the photographer, at Oelwein, Iowa in July, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

Recently delivered Chicago Great Western GP30's, including #201 and #202 closest to the photographer, at Oelwein, Iowa in July, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.By the early 20th century the railroad's financial situation had greatly improved as Stickney sought another round of expansion. The railroad had already opened its only branch in Illinois to DeKalb, a 6-mile spur running via Sycamore completed in October of 1895 via subsidiary DeKalb & Great Western Railway.

It also began branching out to the east and west of its Twin Cities main line during the 1890's, a process which continued into the early 1900's. Most of this trackage came through acquisition of the Wisconsin, Minnesota & Pacific in 1899 which by 1903 connected Mankato to the west, crossed the Great Western at Randolph, then proceed south to link Red Wing, Bellechester (via a short branch), and Rochester.

The latter town also contained a westward spur running back to the CGW main line at Dodge Center. Finally, an extension from Rochester headed east to Winona and south to another CGW connection at McIntire, Iowa before terminating at Osage. The last significant Great Western component was the extension into Omaha.

System Map (1943)

It began with the takeover of the Mason City & Fort Dodge in March of 1901, sold by close friend James J. Hill. The small line was originally completed between its namesake cities on October 24, 1886 and once under Chicago Great Western control, Stickney pushed for Omaha.

First, the 9 miles from Manly to Mason City had to be closed and this segment was ready for service by November 1, 1901. Then, new construction was carried out west of Dodge City in August of 1901. Passing through small agricultural communities like Carroll and Minden it opened to Council Bluffs in the late summer of 1903.

Finally, a trackage rights agreement was secured with Union Pacific later that November to cross its Missouri River bridge and reach Omaha Union Station. With this the Chicago Great Western Railway was complete, operating a network of 1,458 route miles. The system was the classic granger, relying heavily on agricultural traffic.

However, the road did handle other freight including cement, aggregates, manufacturing, various less-than-carload movements, and interchange business (of note was the CGW's openness to work with local interurban carriers, an industry most other large railroads shunned).

Chicago Great Western F3A #103-A leads a long freight through heavy snow and past the depot at Esmond, Illinois in December, 1965. Rick Burn photo.

Chicago Great Western F3A #103-A leads a long freight through heavy snow and past the depot at Esmond, Illinois in December, 1965. Rick Burn photo.The Modern "Corn Belt Route"

The 20th century got off to a rocky start as the CGW entered receivership once more during 1908; an aging Stickney, despite being named a co-receiver of the bankrupt property, quietly resigned on December 21st, electing instead to allow others to run the railroad which he had built.

The reorganization was again brief as the Chicago Great Western Railroad took over the Chicago Great Western Railway's assets on August 19, 1909.

The new CGW saw heavy traffic during World War I when it was operated by the government through the United States Railroad Administration (USRA). The 1920's were a generally good decade until the market crash.

The company's innovation also shown through at this time when it placed gas-electric "Doodlebugs" and streamlined McKeen Cars in service between Chicago and Omaha in 1924, the purpose of which was to cut costs on lightly-patronized trains.

The good times of the "Roarin '20's" would not last, however, as the Great Depression of October, 1929 hit the country, and railroad industry, quite hard. The Great Western at first weathered the troubles but eventually slipped into bankruptcy once more on February 28, 1935.

Chicago Great Western S1 #13 at the road's terminal in Oelwein, Iowa, circa 1965. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago Great Western S1 #13 at the road's terminal in Oelwein, Iowa, circa 1965. American-Rails.com collection.This time the reorganization required much longer due to the economic troubles of the 1930's. However, in comparison to some roads, which spent more than a decade dealing with such proceedings, the CGW was back on its feet before World War II. Its final bankruptcy ended on February 19, 1941 when it became the Chicago Great Western Railway once more.

Given its size and the intensely competitive markets in which it operated the modern CGW was a respectable system boasting a stretch of double-tracked territory extending out of Chicago, hosting one of the earliest trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) services in 1936, and completely dieselizing its motive power fleet by 1949.

While these first-generation models wore an attractive two-tone burgundy/red livery the railroad never bothered with the streamliner craze and instead focused all of its efforts on business development and customer service.

It is interesting that despite Stickney early in the company's history the innovated and resourceful management practices he implemented forever endured.

Chicago Great Western F3A 110-A leads a freight train at Villa Park, Illinois in January, 1968. Rick Burn photo.

Chicago Great Western F3A 110-A leads a freight train at Villa Park, Illinois in January, 1968. Rick Burn photo.Passenger Trains

Blue Bird: (Twin Cities - Rochester)

Bob-O-Link: (Chicago - Rochester)

Great Western Limited: (Chicago - Twin Cities)

Legionnaire: (Chicago - Twin Cities)

Mills Cities Limited: (Kansas City - Twin Cities)

Minnesotan: (Chicago - Twin Cities)

Nebraska Limited: (Twin Cities - Omaha)

Omaha Express: (Twin Cities - Omaha)

Omaha Limited: (Twin Cities - Omaha)

Rochester Special: (Twin Cities - Rochester)

Red Bird: (Twin Cities - Rochester)

Twin Cities Express: (Twin Cities - Omaha)

Twin Cities Limited: (Omaha - Twin Cities)

A matching A-B-A set of new Chicago Great Western F3s, led by #112-C and wearing the road's attractive original livery, are seen here at Oelwein, Iowa on August 22, 1948. The locomotives were about five months old in this scene. Photographer unknown.

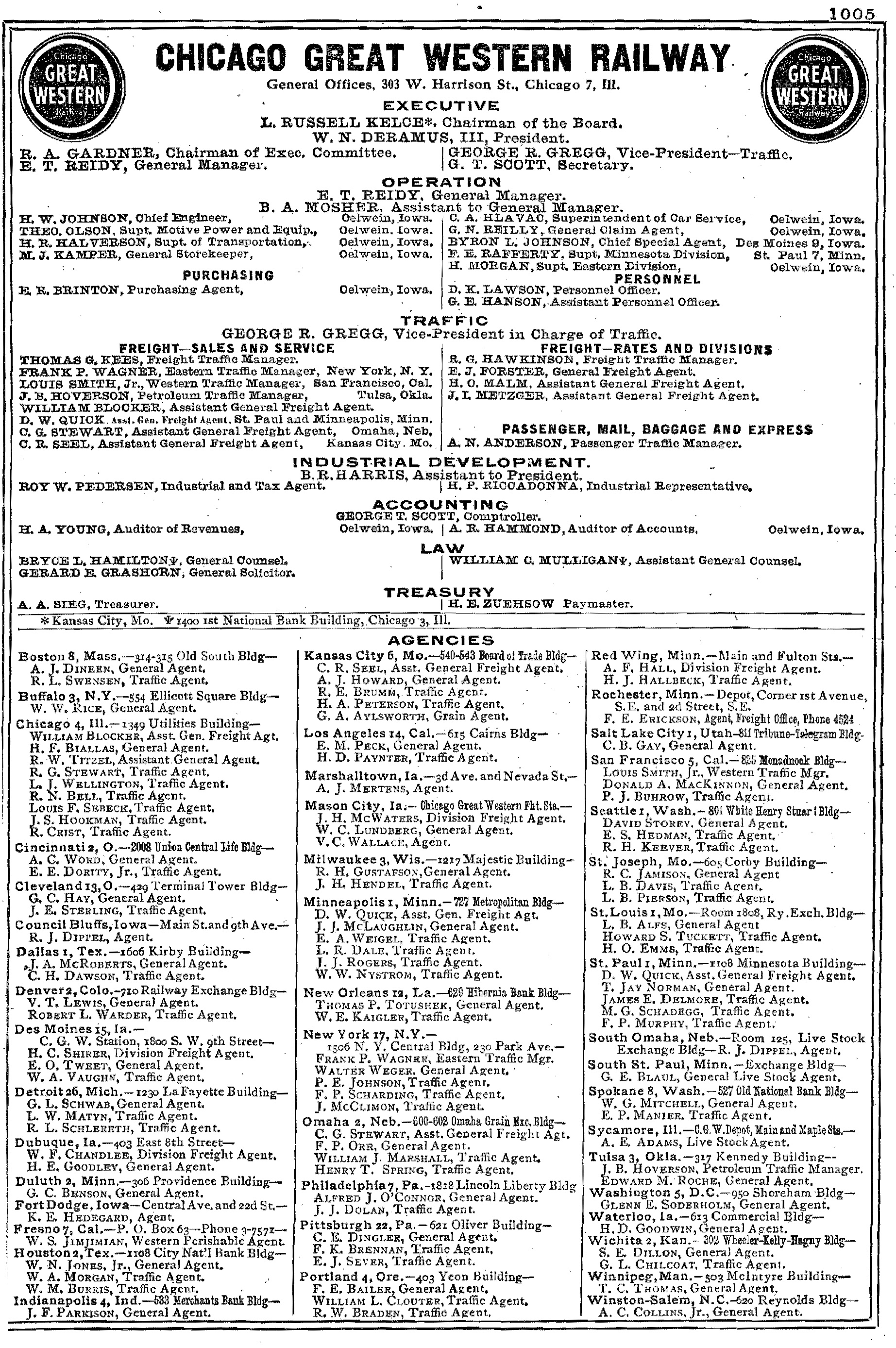

A matching A-B-A set of new Chicago Great Western F3s, led by #112-C and wearing the road's attractive original livery, are seen here at Oelwein, Iowa on August 22, 1948. The locomotives were about five months old in this scene. Photographer unknown.Into the 1950's, under President William N. Deramus III, the CGW launched efforts to significantly cut back its modest passenger services, ending locals and reducing as many through trains as possible. It realized competition from the highways and other railroads proved the concept fruitless.

According to Mike Schafer's book, "More Classic American Railroads," by 1956 there were only two through trains remaining, the Twin Cities - Kansas City, Mills Cities Limited, and Twin Cities - Omaha, Nebraska Limited/Twin City Limited.

The company also took steps to reduce operating costs associated with depots by demolishing these structures for ugly but utilitarian cinder-block buildings.

One of the CGW's classic long freights between Popular Avenue and York Streets at Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1962. Rick Burn photo.

One of the CGW's classic long freights between Popular Avenue and York Streets at Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1962. Rick Burn photo.The Twin Cities - Kansas City ended on April 27, 1962 when trains #6 (northbound) and #5 (southbound) made their final runs while the Twin Cities - Omaha serviced lasted a bit longer until September 29, 1965 when eastbound/northbound train #14 departed Omaha's Burlington Station for the final time.

The focus then rested squarely on freight where the railroad became famous for its propensity to operate extremely long, 200-car consists.

According to Mr. Grant this was actually a long-held practice on CGW to increase efficiency and reduce operating costs, dating back to October, 1894 when it had tested an 84-car consist between St. Paul and Oelwein.

Chicago Great Western RS2 #56 switches the Hormel plant in Austin, Minnesota in February, 1964. Rick Burn photo.

Chicago Great Western RS2 #56 switches the Hormel plant in Austin, Minnesota in February, 1964. Rick Burn photo.Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | 8-10 | 1947 | 3 |

| S1 | 11-15 | 1948 | 5 |

| RS2 | 50-57 | 1949 | 8 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DS-4-4-1000 | 32-41 | 1949 | 10 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 5-7 | 1936 | 3 |

| SW900 | 5 | 1957 | 1 |

| NW2 | 16-31, 42 | 1948-1949 | 17 |

| TR2 | 58A-66A, 58B-66B | 1948-1949 | 18 |

| F3A | 101A-115A, 101C-115C, 150-152 | 1946-1949 | 33 |

| F3B | 101B-112B, 101D-104D | 1947-1949 | 16 |

| F7B | 113B-116B, 108D-116D, 116E, 116F, 116G | 1949-1951 | 16 |

| GP7 | 120-121 | 1951 | 2 |

| GP9 | 120 | 1956 | 1 |

| F7A | 153-156 | 1949 | 4 |

| GP30 | 201-208 | 1963 | 8 |

| SD40 | 401-409 | 1966 | 9 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| B-3 Through B-8 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| C-8 Through C-14 | American | 4-4-0 |

| D-1 Through D-4 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| E-1 Through E-7 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| F-2 Through F-7b | Prairie | 2-6-2 |

| G-1 Through G-4 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| H-1, J-2 Through J-2s | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| K-1 Through K-6 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| L-1 Through L-3 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| M-1 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| T-1 Through T-3 | Texas | 2-10-4 |

A quartet of Chicago Great Western GP30s, led by #201, are at Fair Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1966. Rick Burn photo.

A quartet of Chicago Great Western GP30s, led by #201, are at Fair Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1966. Rick Burn photo.Chicago & North Western Merger

During January of 1957 the Great Western's final president took the helm, Edward Reidy. He did his best to maintain a quality railroad by acquiring new second-generation diesels, maintaining a conservative stance towards spending, offering high top notch customer service, and operating freights as long and as fast as possible.

Alas, government regulations, rising costs, the surrounding competition, and other issues made a regional carrier like the Great Western quite vulnerable.

During the postwar years it had considered several different mergers with the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway (Frisco), Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy), Chicago & Eastern Illinois, Kansas City Southern, Rock Island, and Soo Line.

In hindsight, any of those choices would likely have been better than its ultimate choice, the Chicago & North Western. The merger was finalized on July 1, 1968 and the C&NW, already in a weak financial condition, wanted only the Great Western's Kansas City gateway.

Much of the rest was promptly abandoned, a fact greatly resented by CGW employees. The Chicago Great Western was certainly one of the more interesting granger roads and will forever be remembered for its innovation and commitment to not only itself but also the customers it served.

Photos

A group of Chicago Great Western 'F' units, led by F3A #103C have a long freight at Fair Street in Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1961. Note the GP7 wedged in and the North Shore Line right-of-way at left. Rick Burn photo.

A group of Chicago Great Western 'F' units, led by F3A #103C have a long freight at Fair Street in Elmhurst, Illinois in February, 1961. Note the GP7 wedged in and the North Shore Line right-of-way at left. Rick Burn photo. Classic CGW power, with F3A #101-C closest to the photographer, layover at the Oelwein Shops in Iowa in March, 1967. Little remains of CGW's most important maintenance facility today. Rick Burn photo.

Classic CGW power, with F3A #101-C closest to the photographer, layover at the Oelwein Shops in Iowa in March, 1967. Little remains of CGW's most important maintenance facility today. Rick Burn photo.Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Recent Articles

-

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase. -

CSX Advances Locomotive Technology to Cut Fuel Use and Emissions

Feb 19, 26 09:43 AM

CSX recently highlighted major progress on its ongoing efforts to reduce fuel consumption, cut greenhouse-gas emissions, and improve operational efficiency across its freight rail network through adva… -

Ohio Railway Museum Unveils “Vision for the Future” Plan

Feb 19, 26 09:39 AM

The Ohio Railway Museum (ORM), one of the nation’s oldest all-volunteer rail preservation organizations, has laid out an ambitious blueprint aimed at transforming its organization. -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils $38M Expansion

Feb 19, 26 09:24 AM

Western Maryland Railway F7 236 points towards the Mount Clare Roundhouse in Baltimore as part of the B&O Museum. -

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic To Repower Two FPA4s

Feb 19, 26 09:21 AM

A pair of classic, streamlined Alco/MLW FPA4 locomotives that have become signature power on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) are slated for a major mechanical transformation. -

Ohio's Dinner Train Rides At The CVSR

Feb 19, 26 09:18 AM

While the railroad is well known for daytime sightseeing and seasonal events, one of its most memorable offerings is its evening dining program—an experience that blends vintage passenger-car ambience… -

Indiana Dinner Train Rides In Jasper

Feb 19, 26 09:16 AM

In the rolling hills of southern Indiana, the Spirit of Jasper offers one of those rare attractions that feels equal parts throwback and treat-yourself night out: a classic excursion train paired with… -

New Hampshire Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:12 AM

The state's murder mystery trains stand out as a captivating blend of theatrical drama, exquisite dining, and scenic rail travel. -

New York Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:07 AM

New York State, renowned for its vibrant cities and verdant countryside, offers a plethora of activities for locals and tourists alike, including murder mystery train rides! -

UP, NS Set April 30 Date To Refile Merger Application

Feb 18, 26 04:36 PM

Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern have told federal regulators they will submit a revised merger application on April 30, restarting the formal review process for what would become one of the most co… -

CTDOT May Swap Shore Line East’s Electrics For Diesels

Feb 18, 26 04:20 PM

Connecticut’s Shore Line East (SLE) commuter rail service—one of the state’s most scenic and strategically important passenger corridors—could soon see a major operational change. -

NPS Awards $1.93M To Sioux City Railroad Museum

Feb 18, 26 01:21 PM

The Sioux City Railroad Museum has received a $1.93 million National Park Service grant aimed at pushing the museum’s long recovery from the June 2024 flooding. -

$1.3M Mott Foundation Grant To Help Rebuild Rio Grande 2-8-2 No. 464

Feb 18, 26 09:43 AM

A $1.3 million grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation will fund critical work on steam locomotive No. 464, the railroad’s 1903-built 2-8-2 “Mikado” that has been out of service awaiting heavy… -

NS Unveils Third “Landmark Series” Locomotive

Feb 18, 26 09:38 AM

Norfolk Southern has officially introduced ES44AC No. 8184, the third locomotive in its new “Landmark Series,” a program that spotlights the historic rail cities and communities that helped shape both… -

WMSR's Georges Creek Division: Reviving A Long-Dormant Line

Feb 18, 26 09:34 AM

In 2024 the WMSR announced it was rebuilding part of the old WM. The Georges Creek Division will provide both heritage passenger service and future freight potential in a region once defined by coal… -

Chesapeake & Ohio 614 Restoration Pushes Forward

Feb 18, 26 09:32 AM

One of the most recognizable mainline steam locomotives to survive the post–steam era, C&O 614, is steadily moving through an intensive return-to-service overhaul. -

Montana Dinner Train Rides Near Lewistown

Feb 18, 26 09:30 AM

The Charlie Russell Chew Choo turns an ordinary rail trip into an evening event: scenery, storytelling, live entertainment, and a hearty dinner served as the train rumbles across trestles and into a t… -

Wisconsin Dinner Train Rides In North Freedom

Feb 18, 26 09:18 AM

Featured here is a practical guide to Mid-Continent’s dining train concept—what the experience is like, the kinds of menus the museum has offered, and what to expect when you book. -

Pennsylvania Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:09 AM

Pennsylvania, steeped in history and industrial heritage, offers a prime setting for a unique blend of dining and drama: the murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Jersey Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:06 AM

There are currently no murder mystery dinner trains available in New Jersey although until 2023 the Cape May Seashore Lines offered this event. Perhaps they will again soon! -

Huckleberry Railroad: Riding Narrow-Gauge Steam In Michigan!

Feb 18, 26 09:03 AM

The Huckleberry Railroad is a tourist attraction that is part of the Crossroads Village & Huckleberry Railroad Park located in Flint, Michigan featuring several operating steam locomotives. -

New York & Lake Erie Unveils M636 No. 636 In New Colors (2025)

Feb 17, 26 02:05 PM

In mid-May 2025, railfans along the former Erie rails in Western New York were treated to a sight that feels increasingly rare in North American railroading: a big M636 in new paint. -

First Siemens “Northlander” Trainset Arrives In Ontario

Feb 17, 26 11:46 AM

Ontario’s long-awaited return of the Northlander passenger train took a major step forward this winter with the arrival of the first brand-new Siemens-built trainset in the province. -

Sound Transit Set to Launch Cross-Lake Service

Feb 17, 26 10:09 AM

For the first time in the region’s modern transit era, Sound Transit light rail trains will soon carry passengers directly across Lake Washington -

Michigan’s Old Road Dinner Train Still Seeks New Home

Feb 17, 26 10:04 AM

In May, 2025 it was announced that Michigan's Old Road Dinner Train was seeking a new home to continue operations. As of this writing that search continues. -

WMSR Acquires Conemaugh & Black Lick SW7 No. 111

Feb 17, 26 10:00 AM

In a notable late-summer preservation move, the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) announced in August 2025 that it had acquired former Conemaugh & Black Lick Railroad (C&BL) EMD SW7 No. 111. -

MBTA Unveils New Haven-Inspired Locomotive

Feb 17, 26 09:58 AM

he Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority has pulled back the curtain on its newest heritage locomotive, F40PH-3C No. 1071, wearing a bold, New Haven–inspired paint scheme that pays tribute to the… -

Missouri Dinner Train Rides In Branson

Feb 17, 26 09:53 AM

Nestled in the heart of the Ozarks, the Branson Scenic Railway offers one of the most distinctive rail experiences in the Midwest—pairing classic passenger railroading with sweeping mountain scenery a… -

Texas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:49 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:48 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

RTA To Become The Northern Illinois Transit Authority

Feb 16, 26 12:49 PM

Later this year, the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)—the umbrella agency that plans and funds public transportation across the Chicago region—will be reorganized into a new entity: the Norther… -

CPKC Holiday Train Sets New Record In 2025

Feb 16, 26 11:06 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City’s (CPKC) beloved Holiday Train wrapped up its 2025 tour with a milestone that underscores just how powerful a community tradition can become. -

Historic Izaak Walton Inn Slated To Close

Feb 16, 26 10:51 AM

A storied rail-side landmark in northwest Montana—the Izaak Walton Inn in Essex—appears headed for an abrupt shutdown, with employees reportedly told their work will end “on or about March 6, 2026.” -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils Restored American Freedom Train No. 1

Feb 16, 26 10:31 AM

The B&O Railroad Museum has completed a comprehensive cosmetic restoration of American Freedom Train No. 1, the patriotic 4-8-4 steam locomotive that helped pull the famed American Freedom Train durin… -

Union Pacific, Wabtec Ink $1.2B Deal To Modernize AC4400 Fleet

Feb 16, 26 10:25 AM

Union Pacific has signed a $1.2 billion agreement with Wabtec to modernize a significant portion of its GE AC4400 fleet, doubling down on the strategy of rebuilding proven high-horsepower road units r… -

CSX Taps Wabtec For $670M Locomotive And Digital Upgrade

Feb 16, 26 10:19 AM

CSX Transportation says it is moving to refresh and standardize a major piece of its operating fleet, announcing a $670 million agreement with Wabtec. -

New Mexico "Dinner" Train Rides

Feb 16, 26 10:15 AM

If your heart is set on clinking glasses while the desert glows at sunset, you can absolutely do that here—just know which operator offers what, and plan accordingly. -

West Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Elkins

Feb 16, 26 10:13 AM

The D&GV offers the kind of rail experience that feels purpose-built for railfans and casual travelers.