Rio Grande's "Chili Line": History, Route, Map

Last revised: February 25, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Denver & Rio Grande Western's so-called "Chili Line" certainly held a catchy title and was appropriately-named given its location in the United States' southwestern region.

The corridor officially became known by the D&RGW as the Santa Fe Branch and when originally built in the late 19th century was envisioned as the road's primary route from Denver to the Mexican border.

Unfortunately, a number of factors precluded this from ever happening although the Rio Grande did prosper into a profitable railroad thanks to leadership that took the company in a different direction and opened new lines to the west.

Over time the Chili Line saw decreasing use as competition increased and was eventually abandoned during the early 1940s.

The history of the Rio Grande has been thoroughly covered over the years in countless books, articles, and other publications highlighting everything from its construction and operation to motive power and individual lines.

The D&RGW holds a mystique and fascination for a multitude of reasons, largely due to its once expansive narrow-gauge operations.

The railroad was originally conceived as a three-foot system but its principal routes were later upgraded to standard-gauge for more efficient service and interchange with other carriers.

However, a collection of its southerly network, located west and south of Alamosa, Colorado maintained its three-foot status until abandonment during the 20th century. One such corridor was the so-called "Chili Line."

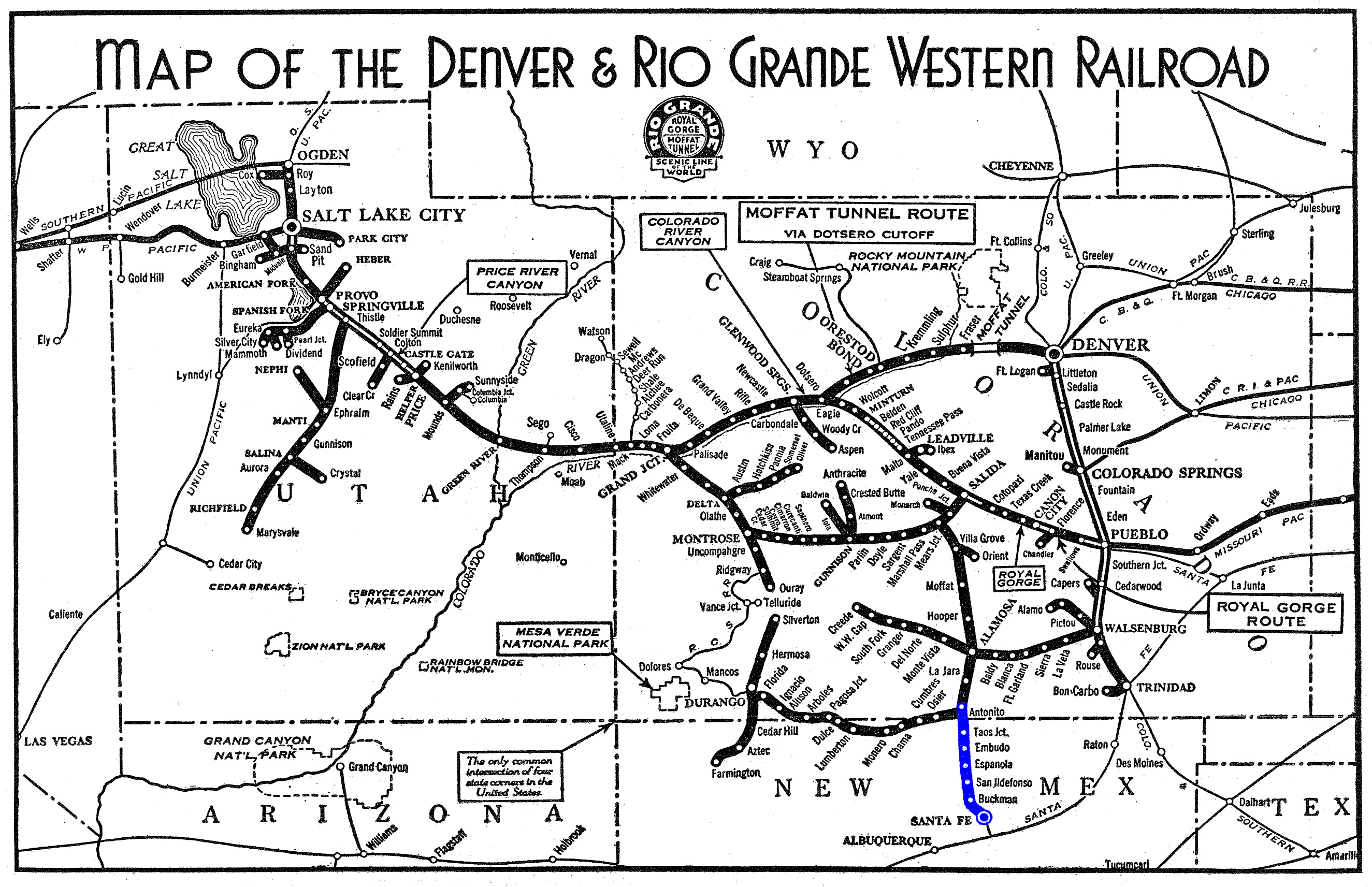

Map

What later became a stub-end branch was envisioned by William J. Palmer, original promoter of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway incorporated on October 27, 1870, as part of a through extension to the Mexican border.

The D&RG began construction on July 28, 1871 and as George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," was the first to employ the three-foot gauge in the United States, the most widely adopted of the narrow-gauge layouts.

Palmer's plan would entail running a line south through New Mexico and reaching El Paso, Texas where an interchange would be established with the Mexican Central Railway. Ultimately, the dream was to have rail service established to Mexico City made up entirely of three-foot gauge.

While Palmer's primary interest with the D&RG did encompass this southern connection what is often unknown is that the railroad was originally projected to stretch west as well to Salt Lake City via Grand Junction, Colorado just as it would eventually do some years later.

This effort began soon after rails reached Pueblo in 1872 when a branch was constructed to Cañon City along the Arkansas River to tap coal mines.

After the financial Panic of 1873 slowed work things resumed in 1876 when Palmer pushed the line south to Cucharas and west to Alamosa, reaching the latter town by July of 1878.

It was then that warfare broke out with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe as both roads staked claim to Raton Pass, a prize AT&SF ultimately claimed.

Unfortunately, the fighting did not end here as both companies then began battling for access into the lucrative mining region near Leadville.

After Jay Gould acquired a large interest in the D&RG he was able to negotiate a treaty between the two parties that led signing the Tripartite Agreement on March 27, 1880.

In this document the companies agreed to a number of stipulations; the D&RG would not attempt to build south of Trinidad, Colorado or Espanola, New Mexico while the Santa Fe turned over its subsidiaries located west of Cañon City to the D&RG and stayed out of Denver and Leadville for 10 years.

While Gould steered the D&RG westward, Palmer did not give up his intentions of completing a southern routing.

With work already underway towards Alamosa, with a goal of reaching Albuquerque, he finished the line as far south as he could at Espanola on December 30, 1880. However, to complete the route to Santa Fe required a bit of corporate ingenuity.

A group of independent businessman, hoping to see the Rio Grande reach the city formed the Texas, Santa Fe & Northern Railroad.

During 1881 grading for the 34-mile line was predominantly completed but funding was exhausted. In 1886 it came under the control of General L.M. Meily which finished the project on January 8, 1887.

It was renamed as the Santa Fe Southern on January 4, 1889 but financial difficulties led to bankruptcy at which point it was acquired by D&RG and renamed again as the Rio Grande & Santa Fe Railroad. The RG&SF was then merged into its parent on August 1, 1908.

Under Rio Grande operation the line became known officially as the Santa Fe Branch although it quickly earned a nickname as the "Chili Line" due to the propensity by local farmers to ship their red chili crop by train.

While agriculture, and some manufactured goods, comprised part of the line's traffic base according to Dr. Hilton's book it was fed largely by timber and related products.

Unfortunately, while the Rio Grande eventually boasted a system stretching more than 2,400 miles, reaching as far west as Salt Lake City and Ogden, the Chili Line wasn't particularly profitable.

The route ran 153 miles between Alamosa-Santa Fe and was plagued by stiff grades (as high as 4% between Embudo and Barranca) with curves as sharp as 22 degrees.

Aside from the main line there were two short branches; one ran between No Agua, New Mexico and Stewart Junction while another extended 16 miles between La Madera via Taos Junction.

The latter was constructed in 1914 to ship out finished lumber from the Halleck & Howard company.

Alas, this operation was brief; unhappy with the quality of timber its mill was shuttered in 1927 along with rail operations soon afterwards.

For whatever reason the Rio Grande chose to leave the Chili Line as a narrow gauge corridor although a third-rail was added along the 28 miles between Alamosa and Antonito in 1901.

Additional infrastructure upgrades included the installation of heavier rail, which allowed larger Class K 28 Mikados to use the line. In any event, the decision to leave most of the route narrow-gauge certainly hurt additional interchange traffic potential with the Santa Fe.

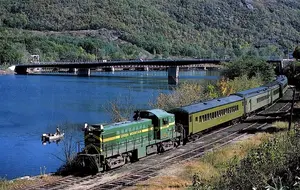

Despite its inherent problems the line has drawn a lot of interest over the years from enthusiasts and historians due to its narrow-gauge operations.

Passenger service remained until the very end with mixed trains, #425 and 426, running until all operations ceased after September 1, 1941. The Rio Grande had received permission to abandon line earlier that January and tracks were removed within days of the final runs.

Recent Articles

-

PRR T1 No. 5550’s Cylinders Nearing Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:53 PM

According to a project update circulated late last year, fabrication work on 5550’s cylinders has advanced to the point where they are now “nearing completion,” with the Trust reporting cylinder work… -

Santa Fe 3415's Rebuild Nears Completion

Feb 15, 26 12:14 PM

One of the Midwest’s most recognizable operating steam locomotives is edging closer to the day it can lead excursions again. -

Ohio Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:59 AM

Among Lebanon Mason & Monroe Railroad's easiest “yes” experiences for families is the Family Pizza Train—a relaxed, 90-minute ride where dinner is served right at your seat, with the countryside slidi… -

Wisconsin Pizza Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:57 AM

Among Wisconsin Great Northern's lineup, one trip stands out as a simple, crowd-pleasing “starter” ride for kids and first-timers: the Family Pizza Train—two hours of Northwoods views, a stop on a tal… -

Illinois "Pizza" Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:55 AM

For both residents and visitors looking to indulge in pizza while enjoying the state's picturesque landscapes, the concept of pizza train rides offers a uniquely delightful experience. -

Tennessee's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:50 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 15, 26 10:48 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

Virginia's Dinner Train Rides In Staunton!

Feb 15, 26 10:46 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a classic scenic train ride with a genuinely satisfying meal—served at your table while the countryside rolls by—the Virginia Scenic Railway was built for you. -

New Hampshire's Dinner Train Rides In N. Conway

Feb 15, 26 10:45 AM

Tucked into the heart of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Valley, the Conway Scenic Railroad is one of New England’s most beloved heritage railways. -

Union Pacific 4014 Begins Coast-To-Coast Tour

Feb 15, 26 12:30 AM

Union Pacific’s legendary 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 is scheduled to return to the main line in a big way this spring, kicking off the railroad’s first-ever coast-to-coast steam tour as part of a broa… -

Amtrak Introduces The Cascades Airo Trainset

Feb 15, 26 12:11 AM

Amtrak pulled the curtain back this month on the first trainset in its forthcoming Airo fleet, using Union Station as a stage to preview what the railroad says is a major step forward in comfort, acce… -

Nevada Northern Railway 2-8-0 81 Returns

Feb 14, 26 11:54 PM

The Nevada Northern Railway Museum has successfully fired its Baldwin-built 2-8-0 No. 81 after a lengthy outage and intensive mechanical work, a major milestone that sets the stage for the locomotive… -

Metrolink F59PH 851 Preserved In Fullerton, CA

Feb 14, 26 11:41 PM

Metrolink has donated locomotive No. 851—its first rostered unit—to the Fullerton Train Museum, where it will be displayed and interpreted as a cornerstone artifact from the region’s modern passenger… -

Oregon's Dinner Train Rides Near Mt. Hood!

Feb 14, 26 09:16 AM

The Mt. Hood Railroad is the moving part of that postcard—a century-old short line that began as a working railroad. -

Maryland's Dinner Train Rides At WMSR!

Feb 14, 26 09:15 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) has become one of the Mid-Atlantic’s signature heritage operations—equal parts mountain railroad, living museum, and “special-occasion” night out. -

Colorado Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:13 AM

If there’s one weekend (or two) at the Colorado Railroad Museum that captures that “living history” spirit better than almost anything else, it’s Wild West Days. -

South Dakota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:11 AM

While the 1880 Train's regular runs are a treat in any season, the Oktoberfest Express adds an extra layer of fun: German-inspired food, seasonal beer, and live polka set against the sound and spectac… -

Kentucky Wild West Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:10 AM

One of KRM’s most crowd-pleasing themed events is “The Outlaw Express,” a Wild West train robbery ride built around family-friendly entertainment and a good cause. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:08 AM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Indiana "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 14, 26 09:06 AM

Indiana offers a unique opportunity to experience the thrill of the Wild West through its captivating train rides. -

B&O Observation "Washington" Cosmetically Restored

Feb 14, 26 12:25 AM

Visitors to the B&O Railroad Museum will soon be able to step into a freshly revived slice of postwar rail luxury: Baltimore & Ohio No. 3316, the observation-tavern car Washington. -

Southern 2-8-2 4501 Returns To Classic Green

Feb 14, 26 12:24 AM

Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum officials announced that Southern Railway steam locomotive No. 4501—the museum’s flagship 2-8-2 Mikado—will reappear from its annual inspection wearing the classic Sou… -

Illinois Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:04 PM

Among Illinois's scenic train rides, one of the most unique and captivating experiences is the murder mystery excursion. -

Vermont ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 12:00 PM

There are currently murder mystery dinner trains offered in Vermont but until recently the Champlain Valley Dinner Train offered such a trip! -

Missouri Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 11:47 AM

Among the Iron Mountain Railway's warm-weather offerings, the Ice Cream Express stands out as a perfect “easy yes” outing: a short road trip, a real train ride, and a built-in treat that turns the who… -

Florida "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:53 AM

This article delves into wild west rides throughout Florida, the historical context surrounding them, and their undeniable charm. -

West Virginia "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:49 AM

While D&GV is known for several different excursions across the region, one of the most entertaining rides on its calendar is the Greenbrier Express Wild West Special. -

Alabama "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:47 AM

Although Alabama isn't the traditional setting for Wild West tales, the state provides its own flavor of historic rail adventures that draw enthusiasts year-round. -

Michigan "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 13, 26 09:46 AM

While the term "wild west" often conjures up images of dusty plains and expansive deserts, Michigan offers its own unique take on this thrilling period of history. -

Grand Trunk Western 4-6-2 No. 5629

Feb 13, 26 12:10 AM

Included here is a detailed look at 5629’s build date and design, key specifications, revenue career on the Grand Trunk Western, its surprisingly active excursion life under private ownership, and its… -

New York Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:19 PM

New York is home to several Easter-themed train rides including the Adirondack Railroad, Catskill Mountain Railroad, and a few others! -

Missouri Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:13 PM

The beautiful state of Missouri is home to a handful of heritage railroads although only one provides an Easter-themed train ride. Learn more about this event here. -

Arizona's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:05 PM

Let's delve into the captivating world of Arizona's Wild West train adventures, currently offered at the popular Grand Canyon Railway. -

Missouri's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:49 PM

In Missouri, a state rich in history and natural beauty, you can experience the thrill of a bygone era through the scenic and immersive Wild West train rides. -

Maine's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:42 PM

Tea trains aboard the historic WW&F Railway Museum promises to transport you not just through the picturesque landscapes of Maine, but also back to a simpler time. -

Pennsylvania Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:09 PM

In this article, we explore some of the most enchanting tea train rides in Pennsylvania, currently offered at the historic Strasburg Rail Road. -

Nevada St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 11:39 AM

Today, restored segments of the “Queen of the Short Lines” host scenic excursions and special events that blend living history with pure entertainment—none more delightfully suspenseful than the Emera… -

Minnesota Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 10:22 AM

Among MTM’s most family-friendly excursions is a summertime classic: the Dresser Ice Cream Train (often listed as the Osceola/Dresser Ice Cream Train). -

Wisconsin's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:54 PM

Through a unique blend of interactive entertainment and historical reverence, Wisconsin offers a captivating glimpse into the past with its Wild West train rides. -

Georgia's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:44 PM

Nestled within its lush hills and historic towns, the Peach State offers unforgettable train rides that channel the spirit of the Wild West. -

North Carolina's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:36 PM

North Carolina, a state known for its diverse landscapes ranging from serene beaches to majestic mountains, offers a unique blend of history and adventure through its Wild West train rides. -

South Carolina's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:16 PM

There is only location in the Palmetto State offering a true dinner train experience can be found at the South Carolina Railroad Museum. Learn more here. -

Rhode Island's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:08 PM

Despite its small size, Rhode Island is home to one popular dinner train experience where guests can enjoy the breathtaking views of Aquidneck Island. -

New York Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:56 PM

Tea train rides provide not only a picturesque journey through some of New York's most scenic landscapes but also present travelers with a delightful opportunity to indulge in an assortment of teas. -

California Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:37 PM

In California you can enjoy a quiet tea train experience aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train, which offers an afternoon tea service. -

Tennessee Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:19 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Ohio "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:34 AM

For those enamored with tales of the Old West, Ohio's railroad experiences offer a unique blend of history, adventure, and natural beauty.