Jersey Central Railroad (CNJ): Map, Rosters, History

Last revised: November 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Central Railroad of New Jersey has gone by a number of different names from CNJ to Jersey Central, and the aforementioned moniker.

Regardless of its many titles the CNJ was a New Jersey institution although it was only regional in operation and, at its peak, just 711 miles in length.

The Jersey Central served much of its home state along with northwestern Pennsylvania, including Easton, Bethlehem, and Wilkes-Barre. It also acquired a part of the old Lehigh & New England during the 1960s to pick up desperately need freight tonnage.

The demise of the CNJ was the result of several factors including a region too saturated with railroads, stiff government regulation, and markets already served by more efficient competitors (such as the Pennsylvania and Reading).

However, for all of these setbacks the railroad was further burdened by heavy taxation through the state of New Jersey.

These issues ultimately led to the railroad’s bankruptcy and inclusion into Conrail in 1976. Today, little remains of the old Jersey Central lines, many of which have been abandoned across its home state and eastern Pennsylvania.

Photos

One of the Jersey Central's double-ended DRX-6-4-2000's, #2005, is seen here tied down in Plainfield, New Jersey, circa 1955. The units were acquired by the CNJ for commuter service to eliminate turning the locomotives at the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City, New Jersey (Communipaw Terminal). Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

One of the Jersey Central's double-ended DRX-6-4-2000's, #2005, is seen here tied down in Plainfield, New Jersey, circa 1955. The units were acquired by the CNJ for commuter service to eliminate turning the locomotives at the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City, New Jersey (Communipaw Terminal). Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.History

The Central Railroad of New Jersey has a complicated and complex corporate history comprising numerous predecessors and subsidiaries which later came together to form the classic CNJ system.

During the 19th century and into the early 20th, prior to the development of efficient highways, the railroad enjoyed a robust and healthy business.

It lay in the busiest and most densely populated region in the country, moving thousands of commuters daily while a diverse traffic based handled everything from oil to milk.

The Jersey Central's earliest ancestry comprised two notable systems; the Elizabethtown & Somerville, incorporated on February 9, 1831, and the Somerville & Easton, incorporated in 1847.

An A-B-A set of Jersey Central DR-4-4-1500's are ahead of a mixed freight at the once important industrial city and interchange point of Phillipsburg, New Jersey in the fall of 1948. John Maris photo.

An A-B-A set of Jersey Central DR-4-4-1500's are ahead of a mixed freight at the once important industrial city and interchange point of Phillipsburg, New Jersey in the fall of 1948. John Maris photo.The E&S took some time to get under way but finally did so on August 13, 1836 when it opened roughly 2 miles between Elizabeth and Elizabethport along the mouth of the Arthur Kill (until 1864 the CNJ operated ferry service between Elizabethport and New York City).

At the time trains were only horse-drawn; steam power did not arrive until January 1, 1839 when the system had reached Plainfield.

Finally, on January 2, 1842 service extended to Somerville, completing the road's original charter. The Somerville & Easton began construction soon after its incorporation, opening between Somerville and White House on September 25, 1848.

The creation of the CNJ was a result of the S&E acquiring the E&S, changing the name of both as the Central Railroad Company of New Jersey on April 23, 1849. Like most of the now-classic fallen flags, the CNJ expanded and grew through a combination of new construction and take over of smaller lines.

At A Glance

Jersey City - Elizabeth - Phillipsburg, New Jersey Easton - Bethlehem - Allentown - Wilkes-Barre/Scranton, Pennsylvania High Bridge - Hopatcong Junction - Rockaway, New Jersey Newark - Perth Amboy - South Amboy - Matawan - Red Bank, New Jersey Freehold - Matawan - Highlands, New Jersey Red Bank - Bowentown, New Jersey Lakehurst - Barnegat, New Jersey | |

Soon after the name change the new company continued pushing rails west until it had spanned its home state, opening service to Phillipsburg in 1852.

This town grew into an important commercial center where five major railroads once met; including the CNJ these were the Lehigh & Hudson River; Lehigh Valley; Delaware, Lackawanna & Western; and Pennsylvania Railroad's Belvidere Division.

Logo

Pushing rails beyond Elizabethport to the Hudson River took a bit more work. However, doing so would offer the CNJ nearly-direct service into Manhattan, albeit requiring ferries to do so.

In 1864 it completed an extension across the Newark Bay, via a one-mile long bridge to Jersey City where a small terminal was opened at what is today Liberty State Park.

The facility, referred to as Communipaw Terminal, or Jersey City Terminal, was replaced with a much larger station in 1889 that served as one of the major Hudson River terminals until the postwar period. It was not only the CNJ's primary terminal into New York but also handled the trains of Reading and Baltimore & Ohio.

The completion of the railroad's Jersey City connection constituted its "Central Division" from that point to Phillipsburg. It was the busiest component of the CNJ and carried four to six tracks along the 35-mile corridor between Jersey City and Raritan.

According to the Classic Trains article, "Jersey Central: Coal, Commuters, And A Comet," this high-speed thoroughfare witnessed 300 commuter trains daily, carrying 35,000 riders, in addition to local freights which the railroad referred to as "drills." There were two other major divisions of the CNJ, which will be briefly highlighted below.

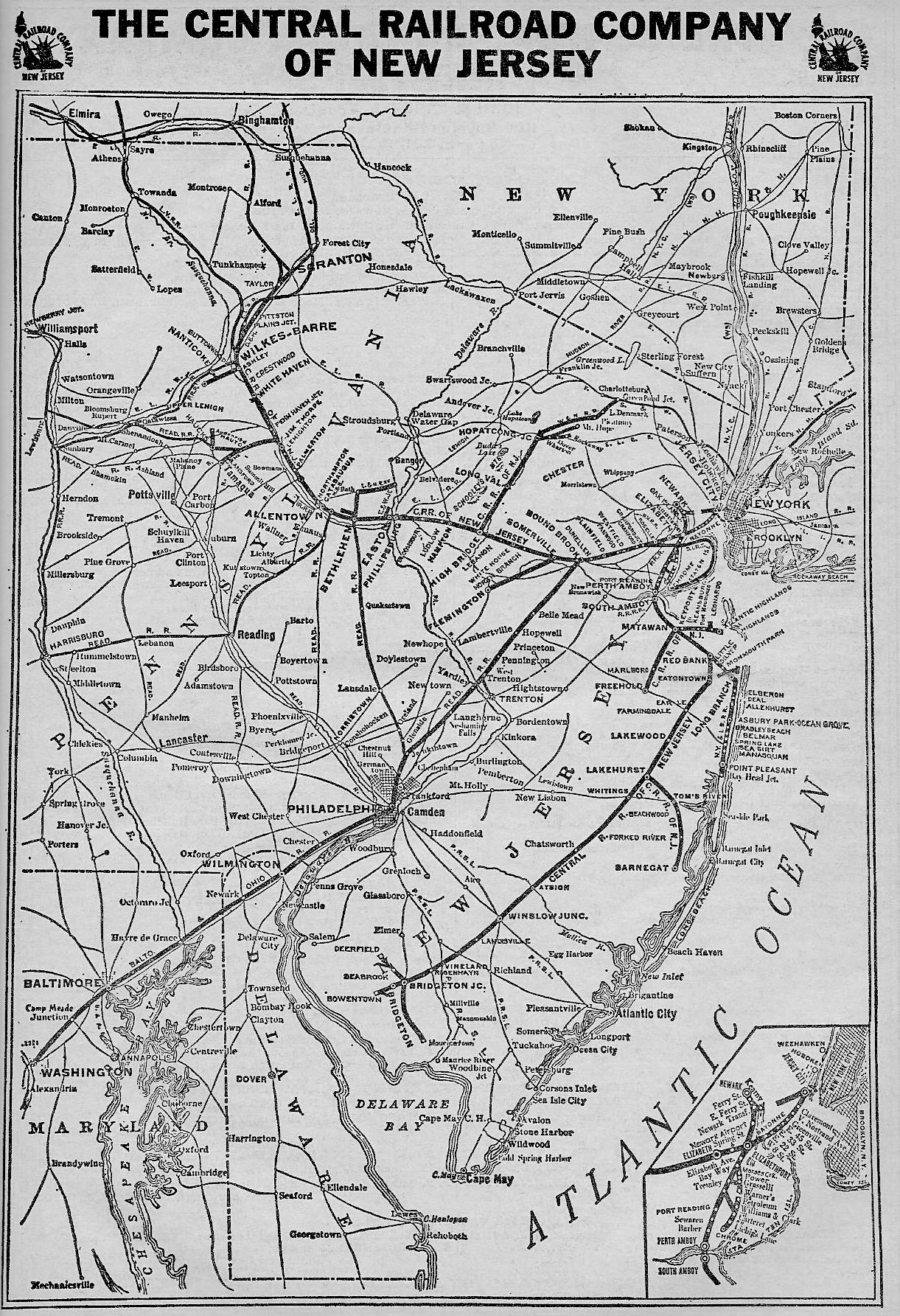

System Map (1969)

Southern Division

The Jersey Central's Southern Division, as its name implies, operated into the state's sparsely-populated southern regions (the so-called, "Pine Barrens") from Red Bank to Bridgeton/Bowentown/Bayside.

During its heyday the trackage handled a variety of freight from agriculture to aggregates. It also moved commuters and vacationers to locations such as Atlantic City, Long Branch, and Tuckerton. The largest component of the Southern Division was the Raritan & Delaware Bay Railroad chartered in 1854.

It was originally intended to link New York with the important Virginia port of Norfolk, via steamship service across the Delaware Bay. While this plan ultimately never materialized the system did construct a significant stretch of trackage across New Jersey.

It opened its first segment in 1860 between Port Monmouth and Bergen Iron Works (Lakewood) via Red Bank. Thanks to a relatively flat topography, grading and construction commenced quickly and by 1862 had reached Winslow where a connection was made with the Camden & Atlantic offering through service to Camden, New Jersey.

A handsome Jersey Central "Train Master," #2410, rests between commuter assignments along the New York & Long Branch at Bay Head Junction, New Jersey on July 15, 1956. Author's collection.

A handsome Jersey Central "Train Master," #2410, rests between commuter assignments along the New York & Long Branch at Bay Head Junction, New Jersey on July 15, 1956. Author's collection.In 1870 the R&DB was renamed as the New Jersey Southern Railroad (later reorganized as the New Jersey Southern Railway in 1880) and extensions beyond Winslow were the result of acquiring the Vineland Railway in 1872 (via lease), which had opened to Bayside in 1871.

The completion of this line constituted the extent of the Southern Division's main line although there were branches later added to the network reaching Tuckerton/Barnegat, Deerfield, and Bivalve while carferry service was established to Woodland Beach, Delaware via Bayside.

Jersey Central H15-44 #1512 has train #3357 at Long Branch, New Jersey in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.

Jersey Central H15-44 #1512 has train #3357 at Long Branch, New Jersey in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.Arguably the most important segment of the Southern Division was the New York & Long Branch Railroad, chartered on April 8, 1868. The line's construction did not begin for some time although the CNJ already held a controlling interest by 1873.

The NY&LB connected the Central's northern New Jersey lines with the NJS properties to the south. It opened for service between Perth Amboy and Long Branch in 1875, eventually extending southward to Bay Head Junction by 1882.

The NY&LB proved a major commuter corridor within a quickly expanding region and rival Pennsylvania Railroad wanted in; it launched plans to build a competing line but ultimately the two roads agreed to mutually share the NY&LB in January of 1882 with the CNJ handling freight duties.

Jersey Central RDC-1s work local service on the four-track main line at Elizabeth, New Jersey, circa 1960. The Pennsylvania Railroad's Northeast Corridor can be seen in the background. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Jersey Central RDC-1s work local service on the four-track main line at Elizabeth, New Jersey, circa 1960. The Pennsylvania Railroad's Northeast Corridor can be seen in the background. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.Lehigh & Susquehanna Division/Pennsylvania Division

The Jersey Central's trackage within Pennsylvania, west of Easton, was known by different names over the years, first as the Lehigh & Susquehanna Division and then later the Pennsylvania, or Penn Division. The territory was the road's vitally important freight corridor, earning it the status of an anthracite carrier.

The division's original moniker was derived from a railroad of the same name, the Lehigh & Susquehanna, founded in 1837 as a component of the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company.

It opened for service in 1843, moving anthracite coal from the Lehigh Canal at White Haven to Wilkes-Barre situated along the North Branch Canal.

The road was slowly extended southward from White Haven over the years reaching Mauch Chunk (later renamed Jim Thorpe) in 1867 and finally Phillipsburg in 1868.

In 1871 the CNJ formally leased the L&S and in the subsequent years added many branches to tap additional mines reaching locations such as Lehigh, Lee, Nanticoke, and Audenreid. Its last notable extension occurred with the opening of the Wilkes-Barre & Scranton in 1888 between Pittston and Scranton.

Jersey Central RS3 #1700 at Jersey City, New Jersey in the winter of 1970. American-Rails.com collection.

Jersey Central RS3 #1700 at Jersey City, New Jersey in the winter of 1970. American-Rails.com collection.This area of eastern Pennsylvania lay in the heart of anthracite country and numerous railroads could be found operating there which included the Lehigh Valley, Erie, Lackawanna, Lehigh & Hudson River, Lehigh & New England, Reading, Delaware & Hudson, Ontario & Western, and even the Pennsylvania.

In addition, cities like Easton, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, and previously-mentioned Phillipsburg grew into robust manufacturing centers while Bethlehem was a steel-producing mecca.

Following the turn of the century, in 1901 the Reading took control of the CNJ, which lasted until 1976 and Conrail (the Reading, itself was acquired by the B&O in 1903).

This railroad was similar to the Jersey Central in that it handled large volumes of anthracite coal from the eastern Pennsylvania coalfields while also carrying considerable merchandise and commuter traffic from the New Jersey, Tri-State, and Philadelphia regions.

The CNJ remained a profitable system until the Great Depression and carried out several improvement projects prior to that time. Classic Trains Magazine notes that it put the first automatic semaphore signal into service in 1893 and upgraded the bridge across Newark Bay as a four-track, 1.4-mile drawbridge in 1926 to handle increasing demand.

Led by SD40 #3063 (ex-Baltimore & Ohio #7484), an eclectic lash-up powers this Jersey Central freight at Green's Bridge, New Jersey on April 19, 1972. Bob Wilt photo/Warren Calloway collection.

Led by SD40 #3063 (ex-Baltimore & Ohio #7484), an eclectic lash-up powers this Jersey Central freight at Green's Bridge, New Jersey on April 19, 1972. Bob Wilt photo/Warren Calloway collection.At its peak, the Central Railroad of New Jersey operated 700 route miles clustered within a dense network that in total boasted some 1,900 track miles!

While the railroad was successful during its early years, as demand for anthracite waned after the 1920s and the impending Great Depression further decimated the business environment, the CNJ fell on hard times. It entered bankruptcy in 1939 and did not emerge until after World War II, in 1949.

It also struggled to deal with New Jersey's increasing tax burden while rising operating/labor costs coupled with declining patronage meant commuter and passenger trains were no longer profitable operations. The CNJ was a finely-tuned operation at the turn of the 20th century.

Its visionaries had comprised a system built for handling commuters and anthracite coal, which they believed would be a viable business virtually forever. Alas, they could never have predicted the rise of the automobile or falling demand for coal; ultimately, the railroad's busy years lasted but a few decades.

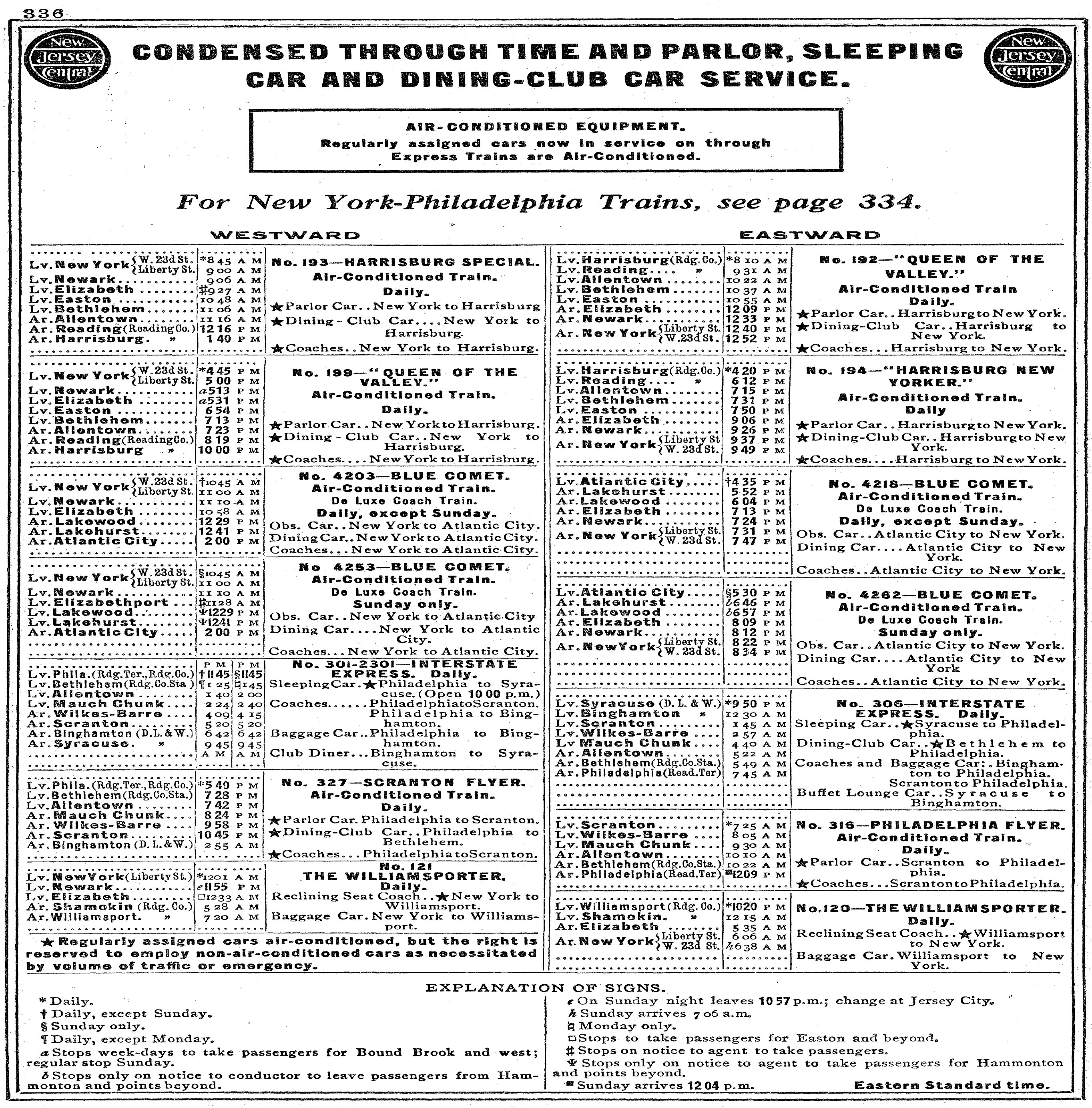

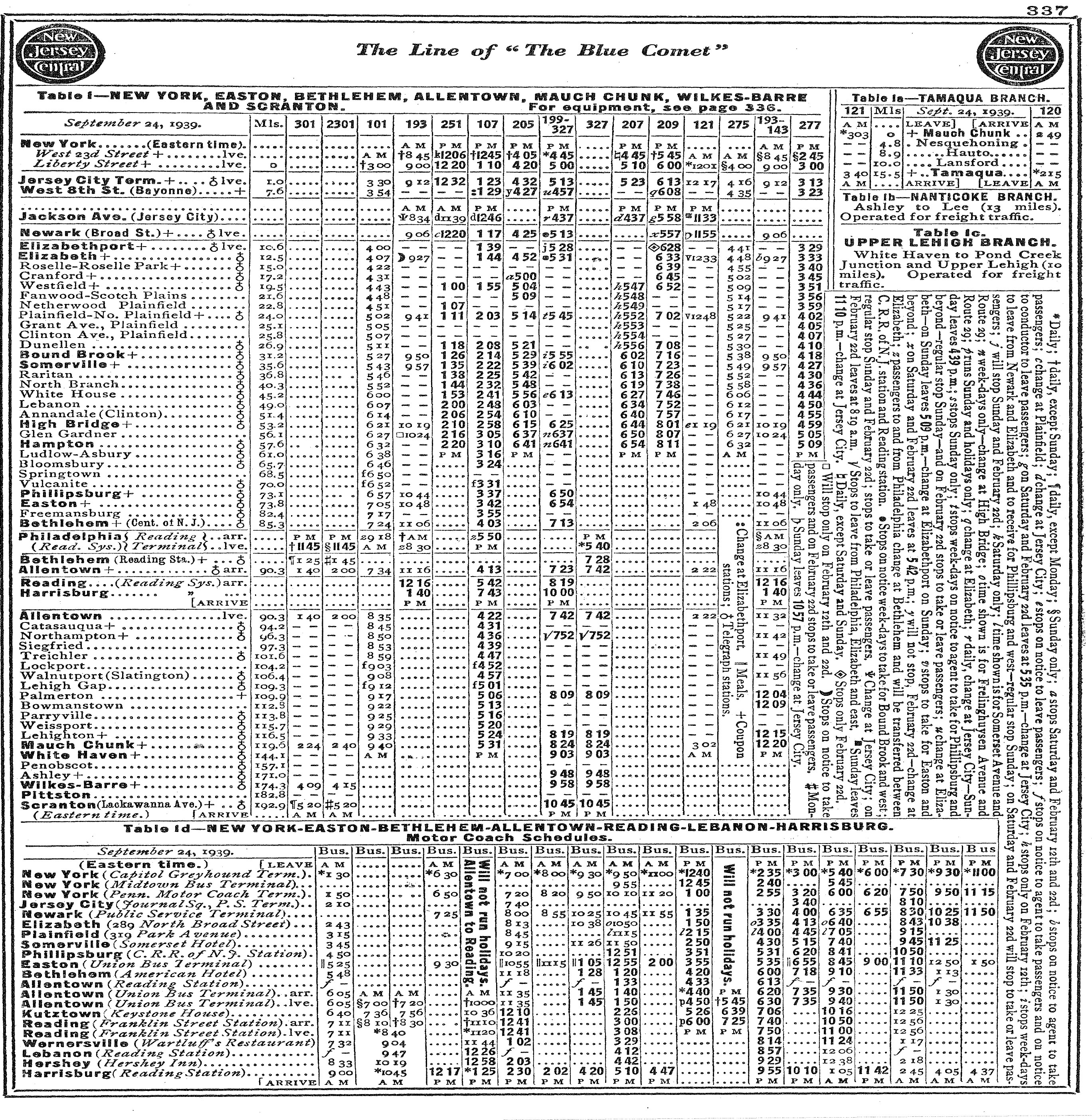

Schedule and Timetables (1940)

The Northeast’s traffic base shrank after World War II as manufacturing moved out of the region and ever-expanding highways pulled away short-haul freight. By the 1960s, the companies mentioned above were facing destitution; there were simply too many railroads and not enough traffic.

Roads like the Reading, LV, and CNJ were hit especially hard as they all relied heavily on anthracite, which was no longer profitable as demand had almost completely disappeared.

In a somewhat ironic twist, the CNJ actually grew during this period when it acquired segments of the former segments of the Lehigh & New England, totaling about 41 miles in Pennsylvania, which had shut down in 1961.

As Walter Kraus notes in his article, "Real Demise Of Rail Line Trailed Coal's Decline," from the August 24, 1989 edition of The Morning Call, the CNJ purchased this trackage for $10 million with the sale made effective on October 31, 1961.

These lines included Tadmor Yard at Bath, the Bethlehem Branch, the Martins Creek Branch, trackage around Catasauqua, and the former Panther Creek Railroad to Tamaqua.

An example of the Jersey Central's early livery, now worn by Norfolk Southern heritage unit SD70ACe #1071. The locomotive is seen here during the Class I's 30th Anniversary celebration at the North Carolina Transportation Museum on July 3, 2012. Warren Calloway photo.

An example of the Jersey Central's early livery, now worn by Norfolk Southern heritage unit SD70ACe #1071. The locomotive is seen here during the Class I's 30th Anniversary celebration at the North Carolina Transportation Museum on July 3, 2012. Warren Calloway photo.Final Years

As red ink continued to flow the CNJ entered its final bankruptcy in 1967. That same year, New Jersey's Aldene Plan went into effect in an effort to curb the significant losses railroads were incurring from passenger/commuter operations.

This move saw a new connection built to the Lehigh Valley at Aldene allowing CNJ trains to reach PRR's Pennsylvania Station in Newark and eliminating service at Jersey City Terminal.

Jersey Central SD40 #3066 (ex-B&O #7487) and #3069 (ex-B&O #7490) lead a westbound freight through Ashley, Pennsylvania along Main Street on June 27, 1971. Author's collection.

Jersey Central SD40 #3066 (ex-B&O #7487) and #3069 (ex-B&O #7490) lead a westbound freight through Ashley, Pennsylvania along Main Street on June 27, 1971. Author's collection.With the closure of JCT, the Newark Bay Drawbridge also became redundant and was eventually razed by the U.S. Coast Guard during the 1980s.

In a last ditch attempt to reduce its considerable losses the CNJ embargoed all lines in Pennsylvania in 1972, which were picked up by the Lehigh Valley.

In the end, nothing worked and the railroad, which boasted perhaps the most patriotic of all railroad logos, Lady Liberty (a logo it acquired in 1944 when the company became known as the "Jersey Central Lines"), quietly disappeared into Conrail on April 1, 1976.

Jersey Central 4-6-2 #821 gets up to speed with a commuter run after just departing eastbound from the Netherwood Station in Plainfield, New Jersey on December 29, 1952. Joe Stark photo.

Jersey Central 4-6-2 #821 gets up to speed with a commuter run after just departing eastbound from the Netherwood Station in Plainfield, New Jersey on December 29, 1952. Joe Stark photo.The Jersey Central was, of course, a small railroad in comparison to most other classic systems. However, for her small size she held numerous achievements and feats.

In addition to those previously mentioned they include the first commercially successful diesel locomotive, The Blue Comet (the CNJ's most successful and famous passenger train connecting Jersey City with Atlantic City), and a four track main line that stretched from Jersey City to Raritan, New Jersey.

Passenger Trains

The Blue Comet: Jersey City - Atlantic City

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alco | RS3 | 1564 | 80107 | 7/1952 | ex-Reading 489; became Conrail 5389 |

| Alco | RS1 | 1200-1204 | 78095-78099 | 6/1950 | - |

| Alco | RS1 | 1205 | 79234 | 9/1951 | - |

| Alco | RSD4 | 1601-1606 | 78745-50 | 11/1951-2/1952 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin | DR-4-4-1500 (B) | K, L, M | 73124-73126 | 11/1947, 7/1948-8/1948 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| Baldwin | DR-4-4-1500 (B) | R, S | 73127-73128 | 9/1948 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| Baldwin | DR-4-4-1500 (A) | 70-79 | 73114-73123 | 11/1947-9/1948 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| Baldwin | DRX-6-4-2000 | 2000-2002 | 73060-73062 | 11/1946-1/1947 | A double-ended cab design for commuter service to the Jersey City terminal. Sublettered for Wharton & Northern. |

| Baldwin | DRX-6-4-2000 | 2003-2005 | 73750-73752 | 8/1948-9/1948 | A double-ended cab design for commuter service to the Jersey City terminal. Sublettered for Wharton & Northern. |

| Baldwin | RS12 | 1206-1208 | 75446-75448 | 1/1953 | - |

| Baldwin | RS12 | 1209 | 75698 | 1/1953 | - |

Budd Company

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budd | RDC-1 | 551-554 | 5919-5922 | 4/1954 | - |

| Budd | RDC-1 | 555-557 | - | - | - |

| Budd | RDC-1 | 558-561 | - | - | ex-NYSW #M1-M4 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | F3B | A, B, C | 4056-4058 | 7/1947 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| EMD | F3B | D, E | 4059-4060 | 7/1947 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| EMD | F7A | 10 | 10230 | 8/1950 | Leased from the B&O (#4503); built as B&O #243A |

| EMD | F7A | 11-12 | 15907, 15916 | 1/1952 | Leased from the B&O (#4576-4577); built as B&O #933 and #933A |

| EMD | F7A | 13-14 | 15918, 15910 | 1/1952 | Leased from the B&O (#4581-4582); built as B&O #937A and #9492 |

| EMD | F7A | 15 | 15911 | 1/1952 | Leased from the B&O (#4584); built as B&O #941 |

| EMD | F7A | 16-17 | 15913, 15922 | 1/1952 | Leased from the B&O (#4588-4589); built as B&O #945 and #945A |

| EMD | F7A | 20-22 | 9032-9033, 12615 | 7/1951 | ex-N&W #3689-3690, #3697; built as Wabash #689-690, #697 |

| EMD | F7A | 23-25 | 15038, 15040, 15047 | 1/1952 | ex-N&W #3703, 3#705, #3712; built as Wabash #703, #705, #712 |

| EMD | F7A | 26-29 | 17069-17070, 17072-17073 | 9/1952 | ex-N&W #3714-3715, #3717-3718; built as Wabash #714-715, #717-718 |

| EMD | F3A | 50-59 | 4046-4055 | 7/1947 | Sublettered for Central Railroad of Pennsylvania. |

| EMD | GP7 | 1520-1525 | 17098-17103 | 11/1952-12/1952 | Became Conrail #5676-5677, #5681, #5902-5904 |

| EMD | GP7 | 1526 | 17104 | 11/1952 | Wrecked on 9/15/1958, involved in the Newark Bay Bridge accident. |

| EMD | GP7 | 1526 (2nd) | 17106 | 12/1952 | Renumbered from 1528 (1st). |

| EMD | SD40 | 3061-3069 | 33161-33169 | 5/1967 | ex-B&O #7482-7490; became Conrail #6285-6292 |

Fairbanks-Morse

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | H16-44 | 18 (2nd) - 19 (2nd) | 16L697-16L698 | 12/1952 | ex-B&O #6700-6701 |

| FM | H15-44 | 1500 | 15L6 | 3/1948 | Former demontrator #1500. Purchased by the CNJ in 9/1948. |

| FM | H15-44 | 1501-1513 | 15L15-15L27 | 1/1949-4/1949 | - |

| FM | H16-44 | 1514-1517 | 16L304-16L307 | 7/1950 | - |

General Electric/Ingersoll-Rand

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boxcab 60T | 1000 | 1925 | 1 |

Steam Roster (Post 1900)

| Wheel Arrangement | Class (1919) | Class (1945) | Road Numbers | Quantity | Builder | Completion Date | Retirement Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-6-0 | L5 | T28 | 150-166 | 17 | Brooks (Alco) | 1900-1901 | 1934-1952 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L5a | - | 167-168 | 2 | Brooks (Alco) | 1902 | 1936 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L5b | T32 | 169-174 | 6 | Brooks (Alco) | 1903 | 1936-1953 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L5c | T32 | 175-184 | 10 | Brooks (Alco) | 1906 | 1934-1953 | Camelback |

| 2-6-2T | J1 | SU23 | 200-219 | 20 | Baldwin | 1902-1903 | 1935-1945 | |

| 2-6-2T | J1 | SU23 | 220-224 | 5 | Baldwin | 1904 | 1945 | Ex-Long Island |

| 4-6-4T | H1s | SU31 | 225-230 | 5 | Baldwin | 1923 | 1947-1950 | |

| 0-8-0 | E2s | 8553 | 295-304 | 10 | Schenectady (Alco) | 1923 | 1951-1955 | |

| 0-8-0 | E3s | 8561 | 305-314 | 10 | Baldwin | 1927 | 1952-1955 | |

| 0-8-0 | E4s | 8564 | 315-319 | 5 | Baldwin | 1929 | 1955 | |

| 0-8-0 | E4sas | 8564 | 320-324 | 5 | Baldwin | 1930 | 1955 | |

| 4-8-0 | K1 | TW40 | 430-480 | 51 | Brooks (Alco) | 1899-1901 | 1934-1948 | Camelback |

| 4-4-2 | P1a | - | 572-574 | 3 | Baldwin | 1902 | 1928-1930 | Camelback |

| 4-4-2 | P6s | A28 | 590-595 | 6 | Brooks (Alco) | 1901-1902 | 1946-1947 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L3 | T26 | 600-630 | 31 | Brooks (Alco) | 1902 | 1934-1950 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L3s | T34 | 631-635 | 5 | Baldwin | 1902 | 1946-1950 | Camelback |

| 2-8-0 | I5 | C44 | 650-665 | 16 | Brooks (Alco) | 1903, 1905 | 1934-1940 | Camelback |

| 2-8-0 | I4 | - | 675-684 | 10 | Brooks (Alco) | 1906 | 1948-1953 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L6as | - | 750-759 | 10 | Baldwin | 1910 | 1953-1954 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L7s | T38 | 760-769 | 10 | Baldwin | 1912 | 1948-1954 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L7as | T38 | 770-779 | 10 | Baldwin | 1913-1914 | 1950-1956 | Camelback |

| 4-6-0 | L8s | T40 | 780-789 | 10 | Baldwin | 1918 | 1950-1954 | Camelback |

| 4-4-2 | P8 | - | 800-802 | 3 | Reading Shops | 1912 | 1938-1940 | Camelback |

| 4-4-2 | P7s | - | 803-805 | 3 | Reading Shops | 1912 | 1935-1937 | Camelback |

| 4-6-2 | G4s | P52 | 810-814 | 5 | Baldwin | 1930 | 1954-1955 | - |

| 4-6-2 | G1s | P43 | 820-825 | 6 | Baldwin | 1918 | 1948-1954 | - |

| 4-6-2 | G2s | P43 | 826-830 | 5 | Baldwin | 1923 | 1953-1955 | - |

| 4-6-2 | G3s | P47 | 831-835 | 5 | Baldwin | 1928 | 1950-1955 | - |

| 2-8-2 | M1s | M63 | 850-859 | 10 | Brooks (Alco) | 1918 | 1947 | A USRA design. |

| 2-8-2 | M2s | M63 | 860-870 | 11 | Brooks (Alco) | 1920 | 1947-1952 | - |

| 2-8-2 | M2as | M63 | 871-895 | 25 | Brooks (Alco) | 1922 | 1947-1955 | - |

| 2-8-2 | M3s | M63 | 896-915 | 20 | Alco | 1923 | 1947-1952 | - |

| 4-4-0 | - | - | 900 | 1 | Baldwin | 1903 | 1937 | Renumbered 999 in 1923. |

| 2-8-2 | M3as | M63 | 916-935 | 20 | Baldwin | 1925 | 1951-1955 | - |

Jersey Central "Train Master" #2401 with a westbound train at Elizabeth, New Jersey, circa 1960. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Jersey Central "Train Master" #2401 with a westbound train at Elizabeth, New Jersey, circa 1960. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.Postscript

Sadly, the State of New Jersey and its politicians were not kind to the railroad's infrastructure, which would have offered a superb commuter corridor today.

Conrail saw little need for the CNJ lines and either sold or abandoned much of the property; its four-track main is completely gone while only sparse sections remain in use.

The Jersey City Terminal is still standing as a museum but has not seen a train call to her sheds since the controversial Aldene Plan went into effect.

In the end, many historians have felt the railroad was shredded by the state, milked through taxes and abandoned over time without realizing its potential to the Tri-State area.

Today, highways and interstates are choked with traffic as politicians try to find alternatives to ease the burden. While the Jersey Central is now but a memory a few of its lines still serve commuters while others handle some freight. Finally, segments of its Southern Division have been left in place and may see freight service again one day.

Recent Articles

-

New York Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:19 PM

New York is home to several Easter-themed train rides including the Adirondack Railroad, Catskill Mountain Railroad, and a few others! -

Missouri Easter Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:13 PM

The beautiful state of Missouri is home to a handful of heritage railroads although only one provides an Easter-themed train ride. Learn more about this event here. -

Arizona's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 01:05 PM

Let's delve into the captivating world of Arizona's Wild West train adventures, currently offered at the popular Grand Canyon Railway. -

Missouri's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:49 PM

In Missouri, a state rich in history and natural beauty, you can experience the thrill of a bygone era through the scenic and immersive Wild West train rides. -

Maine's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:42 PM

Tea trains aboard the historic WW&F Railway Museum promises to transport you not just through the picturesque landscapes of Maine, but also back to a simpler time. -

Pennsylvania Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 12:09 PM

In this article, we explore some of the most enchanting tea train rides in Pennsylvania, currently offered at the historic Strasburg Rail Road. -

Nevada St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 11:39 AM

Today, restored segments of the “Queen of the Short Lines” host scenic excursions and special events that blend living history with pure entertainment—none more delightfully suspenseful than the Emera… -

Minnesota Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 12, 26 10:22 AM

Among MTM’s most family-friendly excursions is a summertime classic: the Dresser Ice Cream Train (often listed as the Osceola/Dresser Ice Cream Train). -

Wisconsin's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:54 PM

Through a unique blend of interactive entertainment and historical reverence, Wisconsin offers a captivating glimpse into the past with its Wild West train rides. -

Georgia's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 10:44 PM

Nestled within its lush hills and historic towns, the Peach State offers unforgettable train rides that channel the spirit of the Wild West. -

North Carolina's Wild West Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:36 PM

North Carolina, a state known for its diverse landscapes ranging from serene beaches to majestic mountains, offers a unique blend of history and adventure through its Wild West train rides. -

South Carolina's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:16 PM

There is only location in the Palmetto State offering a true dinner train experience can be found at the South Carolina Railroad Museum. Learn more here. -

Rhode Island's Dinner Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 02:08 PM

Despite its small size, Rhode Island is home to one popular dinner train experience where guests can enjoy the breathtaking views of Aquidneck Island. -

New York Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:56 PM

Tea train rides provide not only a picturesque journey through some of New York's most scenic landscapes but also present travelers with a delightful opportunity to indulge in an assortment of teas. -

California Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:37 PM

In California you can enjoy a quiet tea train experience aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train, which offers an afternoon tea service. -

Tennessee Tea Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 01:19 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Ohio "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:34 AM

For those enamored with tales of the Old West, Ohio's railroad experiences offer a unique blend of history, adventure, and natural beauty. -

New York "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:23 AM

Join us as we explore wild west train rides in New York, bringing history to life and offering a memorable escape to another era. -

New Mexico Murder Mystery Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:12 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails -

New York Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:09 AM

While CMRR runs several seasonal excursions, one of the most family-friendly (and, frankly, joyfully simple) offerings is its Ice Cream Express. -

Michigan Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:02 AM

If you’re looking for a pure slice of autumn in West Michigan, the Coopersville & Marne Railway (C&M) has a themed excursion that fits the season perfectly: the Oktoberfest Express Train. -

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 10:07 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar.