Cornelius Vanderbilt: Biography, Facts, Net Worth

Last revised: February 24, 2025

By: Adam Burns

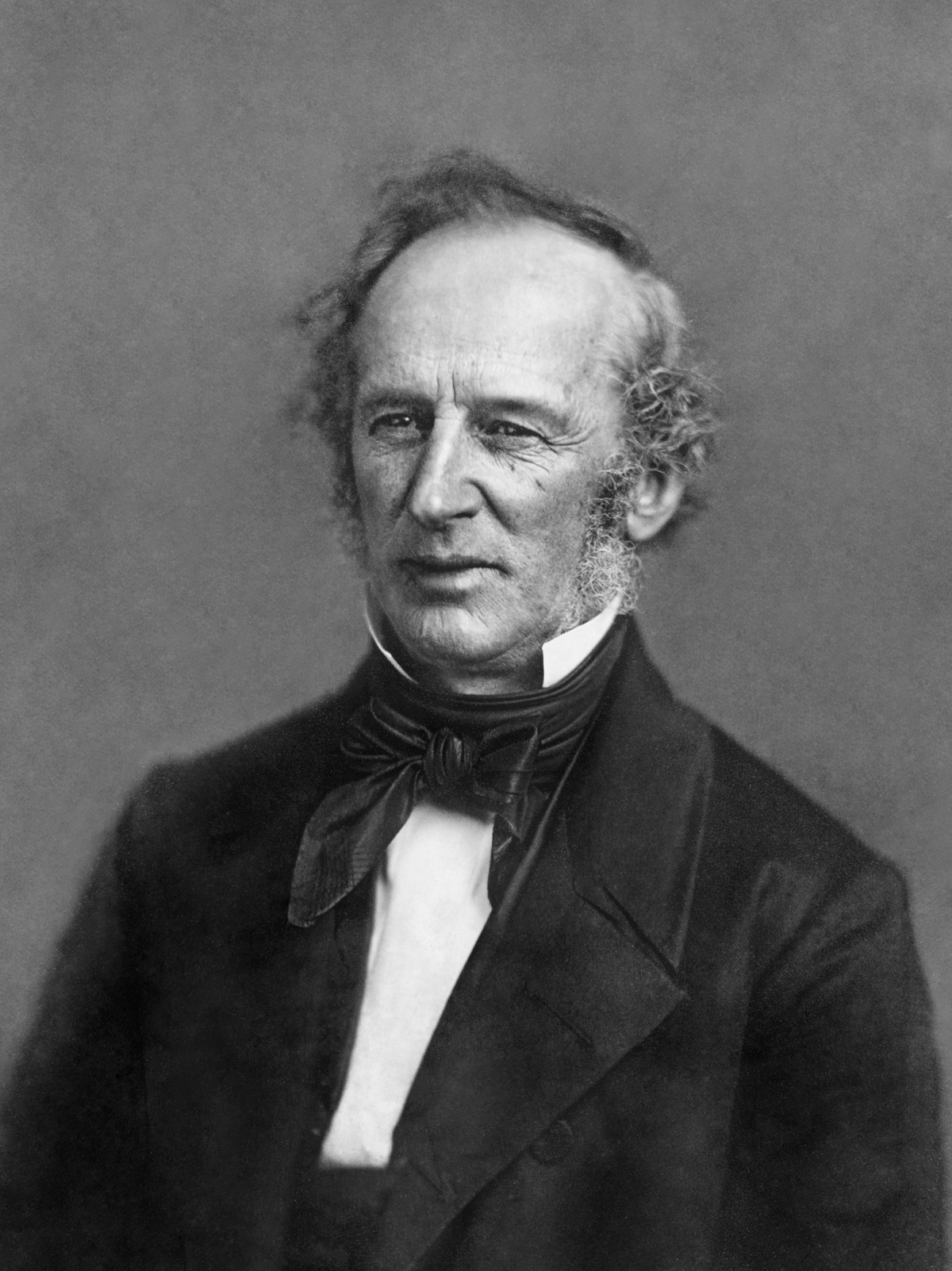

Even today, more than 140 years since his passing, Cornelius Vanderbilt's name continues to evoke power, prestige, and fame. He remains the most revered railroad executive of all time although his direct involvement did not begin until age 70!

For most of his life, this self-taught Staten Islander, with almost no formal education, made millions in the marine/ferry trade.

Vanderbilt was born decades prior to the steam engine's widespread use. However, following its development, he was quick to harness its advantages to amass a fortune which eventually earned him the title of Commodore.

He was a celebrity and legend in his own time, becoming one of the richest individuals in America thanks to his relentless competitiveness.

Vanderbilt fervently believed in laissez-faire economics, using it to great advantage in crushing his rivals. After a lifetime on the sea, he shifted all focus to railroads in 1863.

While Vanderbilt could be rightfully argued as a profiteer with little interest in the public good he was nevertheless fair in business dealings. By the time of his death in 1877 he had laid the foundation for what would become the modern New York Central System.

Background and Early Life

The early life and childhood of Cornelius Vanderbilt is not particularly noteworthy. While it will be discussed here in brief this article will predominantly focus on the Commodore's railroad career.

If interested in a complete biography of Vanderbilt please consider a copy of T.J. Stiles' "The First Tycoon: The Epic Life Of Cornelius Vanderbilt."

It is the quintessential book on his life. Cornelius Vanderbilt was born on May 27, 1794, the fourth child of Phebe Hand and Cornelius Van Der Bilt (original spelling).

His parents were Dutch although their family's history can be traced back to immigrants who settled the colony of "New Netherlands" in 1650.

Overview

Cornelius Van Der Bilt (father) Phebe Hand (mother) | |

Frank Armstrong Crawford Vanderbilt (married, 1869 – 1877) Sophia Johnson (married, 1813 – 1868) | |

By trade, father Cornelius was a farmer and, living so close to New York (then a city of only 33,000), would sell his produce in the city. Ferrying his goods to market required water transport. In Van Der Bilt's case he piloted a two-masted vessel known as a periauger.

This little boat was a Dutch invention specifically meant to carry people and/or goods across the bay. Cornelius never became rich in this trade although it did supplement farming.

Because of their limited means, he and his wife were quite frugal and always saved what disposable income they had. Phebe even lent her silver, earning a profit through the accrued interest.

Industry and Facts

This background set the stage for young Cornelius's future endeavors. As a child he put in long hours on his father's farm and from this impressionable age learned the value of hard work. His father was often overbearing in pursuit of the family farm.

For this reason the lad never had a great interest in formal schooling and quit at the age of 11 to focus exclusively on farming. Vanderbilt's lack of education would prove costly as he climbed the corporate ladder. He never learned to write proper English and instead spelled words phonetically.

This handicap plagued Vanderbilt throughout his life; it was not only embarrassing but also caused his shunning by the social elite for many years. Over the years he partially tackled the issue but always hated putting pen to paper.

By the age of 12, he had grasped the ferry business quite well; coupled with his mother's teachings of savings, borrowing, and collateral he was primed to enter the business world.

This came at the age of 16 when he put a periauger to work, which was technically the property of his parents. After saving enough money he acquired his very own boat by 1813 and his career on the water officially began (that same year, on December 19, he married first cousin, Sophia Johnson).

A New York Central publicity photo featuring the railroad's flagship service, the "20th Century Limited," at Cold Spring, New York in June, 1947.

A New York Central publicity photo featuring the railroad's flagship service, the "20th Century Limited," at Cold Spring, New York in June, 1947.During the War of 1812, Vanderbilt secured a government contract for the movement of military supplies to forts and other projects under construction around New York Harbor.

While the story's validity cannot be confirmed it is said he was awarded this undertaking due to his growing reputation as a competent and able ferryman who offered fair prices.

Vanderbilt's attention to cost, frugality, customers, and his tenacious competitiveness earned him increasingly more money. His aggression continually drove rivals out of business. In some cases they bought him off simply to eliminate the headache.

His usual tactic involved slashing prices so low the opposition would capitulate. He usually lost money himself in the short term but nearly always achieved victory in the long term.

Vanderbilt continually accrued hard capital through either direct cash savings, real estate, or interest earned on loans. As his financial security grew it aided future conquests.

On November 24, 1817, at the age of 23, he took command of the steamboat Mouse, a vessel owned by the wealthy Thomas Gibbons, then one of the nation's most successful merchants.

Steamboats

Steam, of course, was the future in transportation as one no longer needed the winds or currents to power vessels. During his time overseeing Gibbons' fleet he honed his skills as both a seaman and businessman.

On May 16, 1826 Vanderbilt's long-time mentor passed away and the estate passed on to his son. Vanderbilt never cared much for William Gibbons who he saw as weak, a trait the Commodore loathed.

In early 1828 the rising seafarer launched his very own steamboat, the Citizen; a 106-foot, 145-ton sidewheeler. As his means grew, Vanderbilt became a force within the maritime industry.

He acquired evermore steamships and was equally adept at designing his own boats with a constant eye towards cost and speed. A personal clerk who he hired in 1837, Lambert Wardell, once remarked, "He never had a debt and never bought anything on credit. He was economical almost to extremes."

Vanderbilt was believed to be worth a half-million dollars by 1834 and six years later set foot in his new mansion on Staten Island. (Interestingly, he would live in this home for only 13 years. In 1846 he moved into a new home at 10 Washington Place in Manhattan. This would remain his residence until his death.)

An A-B set of New York Central F3's have a westbound manifest as the train passes the eastbound "New England States" (Chicago - Cleveland - Boston) near U.S. Steel's South Works at 87th Street (Chicago) during January, 1951.

An A-B set of New York Central F3's have a westbound manifest as the train passes the eastbound "New England States" (Chicago - Cleveland - Boston) near U.S. Steel's South Works at 87th Street (Chicago) during January, 1951.Earning The Title Of "Commodore"

Until the late 1840's, Vanderbilt had largely concentrated solely on freight and passenger traffic (both ferry and maritime) between New York-Boston, and Long Island Sound in particular.

That changed with the California Gold Rush of 1849. He also became involved with railroads at this time and as his prestige grew so, too, did his celebrity.

The New York Herald reported on March 6, 1851, "Commodore Vanderbilt's character for energy and go-aheadativeness is well known in this community...

He is a man whose resolution is indomitable, and before whose determination obstacles, no matter how great, disappear as the morning dew before a July sun."

The result of the Gold Rush brought thousands of settlers into California, especially into the then-small community of San Francisco.

As an increasing number of Europeans flocked westward, predominantly via steamboat around Cape Horn, California achieved statehood on September 9, 1850; with travel needs so strong, many companies stepped forward to fill the demand as millions of dollars was poured into waterborne transportation.

On April 19, 1849, 226 steamships alone would depart New York for California, carrying some 20,000 travelers. In addition to people, the federal government was interested in shipping mail to and from the west coast. The most practical way was the ocean and South America's Cape Horn.

Recognizing this immense monetary opportunity, Vanderbilt and a few associates believed a canal across Nicaragua was not only practical but could also shave days off the journey.

It was an arduous albeit predominately natural passage, one which would utilize the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

The only man-made section was a 12-mile component along the western fringe. The project was incorporated as the American Atlantic & Pacific Ship Canal Company and following considerable delays, dealings, and political bickering (particularly involving England) Vanderbilt's steamship Prometheus made its way to Greytown, Nicaragua on a trail run from New York.

After arriving at its destination, the goods and passengers were offloaded onto smaller vessels to complete the inland journey. Vanderbilt, himself, was on this trip and became convinced of its merits once he had returned to New York.

On July 14, 1851 the Prometheus again departed New York Harbor, this time on the American Atlantic & Pacific Ship Canal Company's inaugural run. It proved a short-lived venture as the corporation's charter was transferred to another Vanderbilt-controlled entity on August 14th that year, the Accessory Transit Company.

An A-B-A set of New York Central covered wagons led by F7A #1707 is stopped at St. Thomas, Ontario on subsidiary Canadian Southern (CASO) with a westbound freight as the train waits for the electrified London and Port Stanley Railway during September of 1957. Much of this double-tracked route, a very important corridor under the Central, has since been abandoned. David Sweetland photo.

An A-B-A set of New York Central covered wagons led by F7A #1707 is stopped at St. Thomas, Ontario on subsidiary Canadian Southern (CASO) with a westbound freight as the train waits for the electrified London and Port Stanley Railway during September of 1957. Much of this double-tracked route, a very important corridor under the Central, has since been abandoned. David Sweetland photo.Unfortunately, his interest in the Nicaraguan venture was always a tumultuous affair, largely due to a meddling associate, one Joseph L. White.

The operation nevertheless proved quite successful and by the 1850's his nickname as the Commodore, typically reserved for the highest ranking title of a naval officer, was well-established.

He later tapped the transatlantic steamship market (late 1854), a venture which also proved successful. For his many achievements at home and abroad, Vanderbilt's coveted U.S. mail contract always alluded him. Over the next decade he continued to focus on his various maritime dealings.

With a great sense of patriotism he even played a key role during the Civil War. More than once Vanderbilt was offered top positions within President Abraham Lincoln's staff. However, always fiercely against the politic arena he declined each time.

His primary contribution to the war effort involved lending his maritime expertise and gifting the United States his most prized steamship, the five-decked Vanderbilt.

This enormous boat was placed into service on May 5, 1857 where it competed in the transatlantic arena. It was not only large but also fast, able to reduce the New York-Liverpool run from eighteen days to nine. At first, the Navy rejected his offer. However, when the Confederacy unveiled the ironclad CSS Virginia on March 8, 1862 everything changed.

- The CSS Virginia was always referred to as the Merrimack by Union forces as the warship was rebuilt from the salvaged USS Merrimack. -With nearly impenetrable armor the vessel was capable of single-handedly crushing the Union fleet which consisted of traditional wooden-hauled designs.

During that day it sank the USS Cumberland and USS Congress while severely damaging the USS Minnesota. On March 9th, it was met by the United States' own new ironclad, the USS Monitor. The two battled to a stalemate within the James River at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

As an added protection against the Rebels' new creation, President Lincoln and the War Department acquired the Vanderbilt. While it would never engage the CSS Virginia directly the titanic sidewheeler nevertheless kept her from wreaking further havoc.

On May 10, 1862 Union forces captured Norfolk, denying the Virginia port facilities. With nowhere to refit and reequip itself, Confederate forces scuttled the ship on May 11th to avoid its capture.

The Vanderbilt would later earn acclaim chasing another infamous Confederate warship, the CSS Alabama. This sloop-of-war earned recognition as one of the war's most successful raiders. Once again, the Vanderbilt never engaged the Alabama although she did prevent the vessel from creating further trouble along the U.S. coast.

The Alabama was eventually sunk by the USS Kearsarge at the Battle of Cherbourg outside the port of Cherbourg, France on June 19, 1864. For the service to his country, Vanderbilt was awarded a special gold medal following a resolution passed by Congress on January 28, 1864.

A New Era, The Railroads

While the Commodore's direct involvement with railroads did not begin until age 70, he had nevertheless maintained a long history in the industry. It began on November 8, 1833 when he traveled to nearby South Amboy, New Jersey to inspect the recently completed Camden & Amboy Railroad.

At the time the new technology was little more than a novelty although that would soon change. In a decision that nearly killed him, Vanderbilt rode the new contraption that day.

The train derailed en route and despite the traumatic event he held no serious grudge against the iron horse. In fact, Vanderbilt remained keenly interested in the newfangled device.

On November 10, 1837 the New York, Providence & Boston Railroad (NYP&B) opened its first 50 miles southwestward from Providence, Rhode Island. Better known as the "Stonington Railroad" (a future component of the modern New York, New Haven & Hartford) Vanderbilt also rode this line and became convinced of its potential.

He stated it was the fastest way to Boston (from New York) and later, during the summer of 1845, purchased considerable shares in the NYP&B. The following year he also acquired substantial stakes in the Hartford & New Haven Railroad (the precursor to the modern New Haven).

By 1847, he had ascended to the presidency of the Stonington. While the system was well-managed under his direction, the Commodore's interest in railroads remained subdued as he pursued the Nicaragua canal project. This led to his resignation from the Stonington on May 14, 1849.

It was in 1854 that he first became involved with the railroad he would later control, the New York & Harlem Railroad (NY&H). It was the city's first such system, incorporated on April 25, 1831.

While the NY&H maintained a strategic link into downtown Manhattan, running 130 miles from a depot at 26th Street to Chatham, New York, it was not particularly successful (steam locomotives ran only as far as 42nd Street; the remainder was a horse-drawn operation).

Only after Vanderbilt's involvement (On May 18, 1863 he won a directorship and the following day was elected president.), who recognized the railroad's potential, did it thrive.

Prior to this the NY&H had been a poorly managed, unprofitable operation. In 1864 he took control of the nearby Hudson River Railroad, which maintained a roughly parallel route between Albany and New York City.

Interestingly, as Mr. Stiles notes, Vanderbilt's business tactics changed as his railroad involvement deepened. Perhaps, in part, due to his advancing age he often chose diplomacy over open hostility.

Another reason was a result of railroading's very nature; unlike steamships, where one could simply chart a course between two points, railroads operated on fixed infrastructure. Since no singular company then owned a through route between major cities, companies were forced to work together.

Children

Phebe Jane Vanderbilt (1814–1878)

Ethelinda Vanderbilt (1817–1889)

Eliza Vanderbilt (1819–1890)

William Henry "Billy" Vanderbilt (1821–1885)

Emily Almira Vanderbilt (1823–1896)

Sophia Johnson Vanderbilt (1825–1912)

Maria Louisa Vanderbilt (1827–1896)

Frances Lavinia Vanderbilt (1828–1868)

Cornelius Jeremiah Vanderbilt (1830–1882)

George Washington Vanderbilt I (1832–1836)

Mary Alicia Vanderbilt (1834–1902)

Catherine Juliette Vanderbilt (1836–1881)

George Washington Vanderbilt II (1839–1864)

Corporate America of the 19th century was a cutthroat affair with speculators and Wall Street magnates constantly undercutting one another in an attempt to line their own pockets. This was especially true with railroads, the largest businesses in the country.

Unfortunately, with little government oversight, executives like Jay Gould, Daniel Drew, and Collis Huntington often put profits ahead of public service.

Even Vanderbilt could be rightfully accused of this although his empire was not the result of direct conquests. Time and again he added systems as a defensive measures.

After becoming involved in the Harlem, he acquired the competing Hudson River Railroad (via stock control) to protect the NY&H. A plot by Leonard Jerome in 1864 to takeover the original New York Central Railroad (NYC) would have essentially made the NY&H redundant.

Jerome also controlled the Hudson River and his addition of the NYC would have provided him a direct route from New York City to Buffalo via Albany.

Following Vanderbilt's Hudson River conquest he stated: "I said this is wrong, these roads should not clash. Then step-by-step I went into the Hudson River."

Typical of Vanderbilt he was concise and to the point although the actual process of acquiring the system was a chess game, one in which he had become a master. As his railroad portfolios grew, Vanderbilt left the ocean for good in 1864.

New York Central's eastbound "Missourian" (St. Louis - New York) skirts the Mohawk River between Utica and Albany, New York during July of 1952.

New York Central's eastbound "Missourian" (St. Louis - New York) skirts the Mohawk River between Utica and Albany, New York during July of 1952.Interestingly, his railroading career was predominantly from a leadership level. Vanderbilt was rarely involved in the day-to-day, operational management of his properties; instead, he delegated these responsibilities to subordinates. He did, however, regularly take inspection trips.

According to Mr. Stiles' book, "Vanderbilt...set general policies, as well as the overall tone of management...The Commodore created an atmosphere of efficiency, frugality, and diligence, as well as swift retribution for dishonesty or sloth." The Commodore's greatest single acquisition was the original New York Central Railroad.

While his Hudson River and New York & Harlem systems were smaller, they provided the only direct link into downtown Manhattan.

For years, the NYC was controlled by Erastus Corning, a man who, after some time, became an ally of Vanderbilt's. In April, 1864 Corning retired and was replaced by vice president Dean Richmond, another competent railroader who Vanderbilt respected.

During his tenure they enjoyed friendly, mutual traffic interchanges. Alas, he passed away unexpectedly in late 1866 and was subsequently replaced by Henry Keep on December 12, 1866.

Keep had no interest in working with the Commodore and became extremely hostile to Vanderbilt's railroads.

So much so the NYC refused to handle westbound shipments of the Harlem and Hudson River. After many failed attempts at appeasement, Vanderbilt retaliated by refusing to send eastbound NYC shipments beyond the Albany gateway after January 18, 1867.

New York Central & Hudson River Railroad

As the largest American city, New York was a vital market and Vanderbilt controlled the only direct entry. His move scared Keep so badly the man yielded and immediately settled for terms on January 19th. In the aftermath, Keep and his associates sold large blocks of their NYC shares, which Vanderbilt acquired.

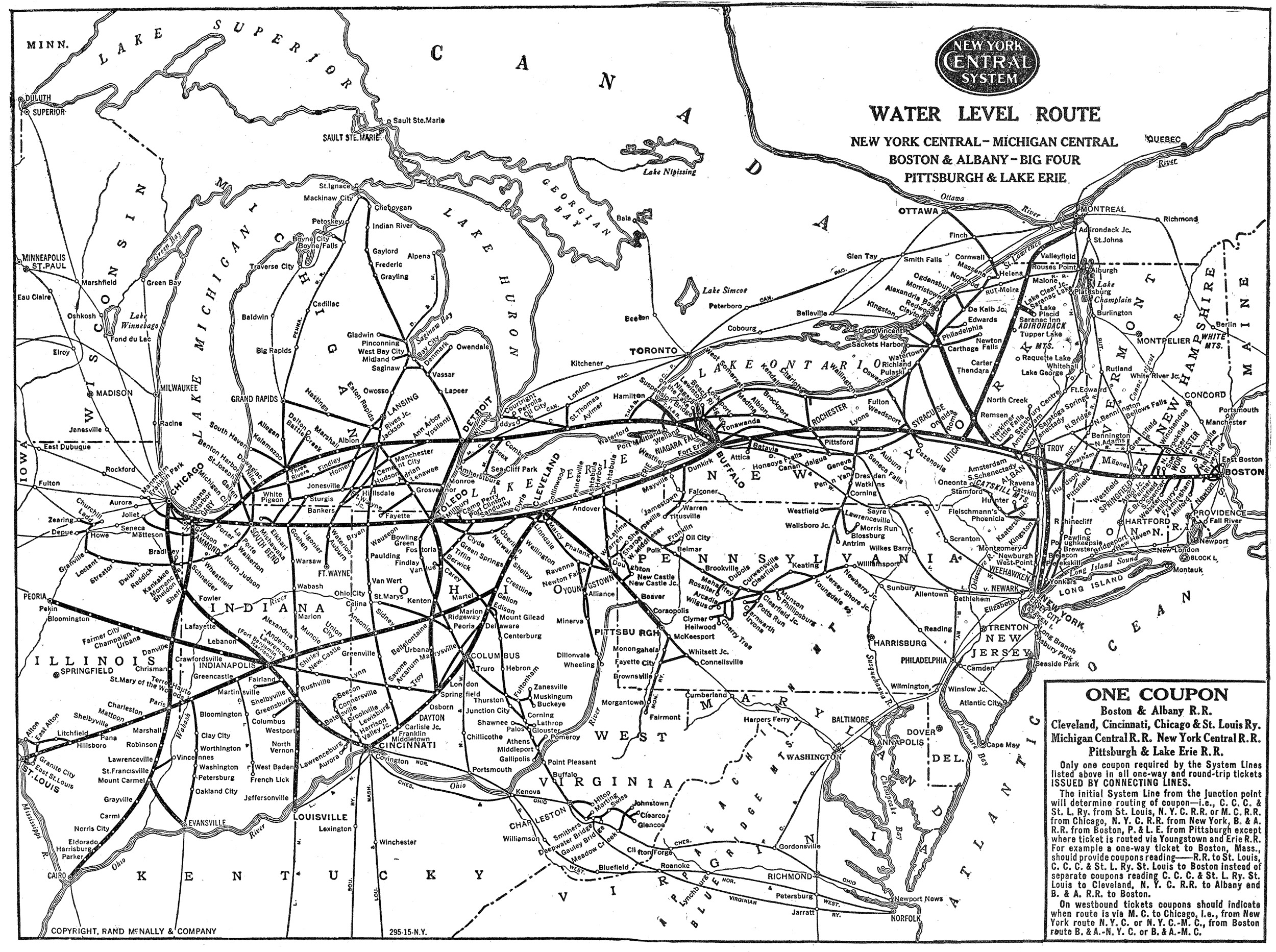

Less than a year later he was named New York Central's president (December 11, 1867). Now under control of all lines between New York and Buffalo, the Commodore formed the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad in 1869; the HRRR and NYC were merged into the new operation while the Harlem was leased.

As Brian Solomon and Mike Schafer note in their book, "New York Central Railroad," another important addition was the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway.

This very large Midwestern had a history tracing as far back as the 1830s and grew through a combination of takeovers and mergers. At its peak the LS&MS connected Buffalo with Chicago via Toledo, Cleveland, and Elkhart.

It also reached Detroit, southern parts of Michigan, and Oil City, Pennsylvania. Vanderbilt assumed the presidency of this road on July 2, 1873 after learning the previous management had nearly bankrupted the railroad. Thanks to his leadership, within a year the company had paid off its debts.

Vanderbilt's last major acquisition occurred on January 1, 1876 when he added the Canada Southern Railway through stock control. Better known by its initials, "CASO," it offered a shorter route through southern Ontario between Buffalo and Detroit. It remained an integral part of the New York Central throughout the 20th century.

After the Commodore's death the New York Central continued to expand reaching Boston; Pittsburgh (through the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie); Wheeling (West Virginia); the coalfields of southern West Virginia (via the Toledo & Ohio Central); Columbus; Cincinnati; Cleveland; St. Louis over the Big Four Route (Cincinnati, Cleveland, Chicago & St. Louis Railway); Detroit (via the Michigan Central); and even Montreal, Quebec.

In addition, the Indiana Harbor Belt provided the NYC terminal and switching services throughout Chicago. In 1868 Vanderbilt sparked the "Erie War" with Jim (James) Fisk, Jay Gould, and Daniel Drew when he attempted to gain control of the Erie Railroad.

An A-B-A set of New York Central "C-Liners" (CFA/B-16-4's) help showcase the railroad's "Pacemaker" high-speed freight service, circa 1952. Ed Nowak photo.

An A-B-A set of New York Central "C-Liners" (CFA/B-16-4's) help showcase the railroad's "Pacemaker" high-speed freight service, circa 1952. Ed Nowak photo.During this time the Erie was one of the largest American railroads. The fight was a battle of wills between Gould and Vanderbilt.

As the Commodore gained increasingly more shares, Gould and his associates issued evermore stock to inflate the Erie's stock value (also known as "watered stock") and prevent Vanderbilt from acquiring majority control.

Gould would eventually win the tilt by bribing the New York state legislature, which authorized the stock as legal. Over the years Cornelius Vanderbilt had disputes with many in the business world such as Drew, Fisk, and others.

His quarrels were almost never personal and he became friends with most later on in life; Gould and Jim Fisk, though, proved an exception.

Net Worth and Estate

The Commodore passed away on January 4, 1877 at the age of 82 having amassed a fortune of nearly $100 million, which would be worth more than $233 billion in today's dollars making him one of the richest Americans in history.

In his will Vanderbilt left $95 million directly to his son, William, with his eight daughters receiving between $250,000 and $500,000 each.

Unlike James Hill, and a number of the other famed railroad tycoons, Vanderbilt was not noteworthy for philanthropy. He did, however, endow $1 million for the establishment of Central University in Nashville, Tennessee. This higher institution of learning became today's prestigious Vanderbilt University.

Recent Articles

-

Virginia Railway Express Surpasses 100 Million Riders

Mar 02, 26 07:57 PM

In October 2025, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) reached one of the most significant milestones in its history, officially carrying its 100 millionth passenger since beginning operations more than… -

Restoration Continues On New Haven RS3 529

Mar 02, 26 11:29 AM

The Railroad Museum of New England's efforts to completely restore New Haven RS3 529 to operating condition as they provide the latest updates on the project. -

American Freedom Train No. 250 Completes FRA Steam Test

Mar 02, 26 10:17 AM

One of the most anticipated steam locomotive restorations in modern preservation reached a major milestone this week as American Freedom Train 4-8-4 No. 250 successfully completed a federally observed… -

Indiana's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 10:00 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Maryland's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:54 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

California's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:46 AM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:42 AM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

New York Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:32 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:30 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

NS Completes 1,000th DC-to-AC Locomotive Conversion

Mar 01, 26 11:26 PM

In October 2025, Norfolk Southern Railway reached one of the most significant mechanical milestones in modern North American railroading, announcing completion of its 1,000th DC-to-AC locomotive conve… -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:11 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

North Carolina Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:09 AM

The springs are typically warm and balmy in the Tarheel State and a few tourist trains here offer Easter-themed train rides. -

Maryland Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:05 AM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:03 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Indiana Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:01 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 09:58 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Metro-North Unveils Veterans Heritage Locomotive

Feb 28, 26 11:02 PM

The Metro-North Railroad marked Veterans Day 2025 with the unveiling of a striking new heritage locomotive honoring the service and sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Pennsylvania's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:46 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Alabama's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:44 AM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Georgia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:43 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:40 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Mexico Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:37 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:35 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

KC Streetcar Ridership Surges With Opening of Main Street Extension

Feb 27, 26 11:24 AM

Kansas City’s investment in modern urban rail transit is already paying dividends, especially following the opening of the Main Street Extension. -

“Auburn Road Special” Excursions To Aid URHS

Feb 27, 26 09:04 AM

The United Railroad Historical Society of New Jersey (URHS) and the Finger Lakes Railway have jointly announced a special series of rare-mileage passenger excursions scheduled for April 18–19, 2026. -

New Jersey Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:53 AM

New Jersey is home to several museums and a few heritage railroads that vividly illustrate its long history with the iron horse. A few host special events for the Easter holiday. -

Washington Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:49 AM

You can find many heritage railroads in Washington State which illustrates its rich history with the iron horse. A few host Easter-themed events each spring. -

South Dakota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:46 AM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:42 AM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Pennsylvania Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:38 AM

Wine tasting trains are a unique and enchanting way to explore the state’s burgeoning wine scene while enjoying a leisurely ride through picturesque landscapes. -

West Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:37 AM

West Virginia, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes and rich history, offers visitors a unique way to explore its rolling hills and picturesque vineyards: wine tasting trains. -

Nebraska Lawmakers Advance UP Tax Incentive Bill

Feb 27, 26 08:31 AM

Nebraska lawmakers are advancing new economic development legislation designed in large part to ensure that Union Pacific Railroad maintains its historic corporate headquarters in Omaha. -

UP And NS Ask FRA To Waive Cab-Signals For Big Boy 4014

Feb 26, 26 01:44 PM

Union Pacific’s famed 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 could see new eastern mileage on Norfolk Southern in 2026—but first, the two railroads are asking federal regulators for help bridging a technology gap… -

Cando Rail & Terminals to Acquire Savage Rail

Feb 26, 26 11:29 AM

Cando Rail & Terminals has signed a definitive agreement to acquire Savage Rail, the U.S. rail-services business of Savage Enterprises LLC. -

Dollywood To Convert Steam Locomotives From Coal To Oil

Feb 26, 26 09:20 AM

Dollywood’s most recognizable moving landmark—the Dollywood Express—will soon look and feel a little different. -

Missouri Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:10 AM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:08 AM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Utah Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:04 AM

Utah, a state widely celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty and dramatic landscapes, is also gaining recognition for an unexpected yet delightful experience: wine tasting trains. -

Vermont Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:02 AM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Amtrak San Joaquins Becomes Gold Runner

Feb 26, 26 08:59 AM

California’s busy state-supported rail link between the Bay Area and the Central Valley entered a new chapter in early November 2025, when the familiar Amtrak San Joaquins name was officially retired. -

Canadian National Marks 30 Years Since Privatization

Feb 25, 26 02:07 PM

Canadian National Railway marked a milestone last fall that helped redefine not only the company, but the modern Canadian freight-rail landscape: 30 years since CN went private. -

Western Rail Coalition: Returning Passenger Trains To Colorado

Feb 25, 26 11:48 AM

Colorado’s passenger-rail conversation is often framed as two separate stories: a Front Range “spine” along I-25, and a harder, longer-term quest to offer real alternatives to the I-70 mountain drive. -

Union Pacific Unveils Full Schedule For Big Boy 4014

Feb 25, 26 09:24 AM

Union Pacific Railroad has released the complete western leg schedule for its groundbreaking 2026 Big Boy No. 4014 Coast-to-Coast Tour. -

Kentucky Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:55 AM

In the realm of unique travel experiences, Kentucky offers an enchanting twist that entices both locals and tourists alike: murder mystery dinner train rides. -

Utah Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:53 AM

This article highlights the murder mystery dinner trains currently avaliable in the state of Utah! -

Rhode Island Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:50 AM

It may the smallest state but Rhode Island is home to a unique and upscale train excursion offering wide aboard their trips, the Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad. -

Oregon Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:45 AM

For those looking to explore this wine paradise in style and comfort, Oregon's wine tasting trains offer a unique and enjoyable way to experience the region's offerings. -

Amtrak Posts Record Ridership and Revenue in Fiscal Year 2025

Feb 24, 26 11:22 PM

Amtrak, the national passenger rail operator, has announced historic results for Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25), reporting the highest ridership and revenue in its history as demand for train travel across t… -

NC By Train Posts Busiest Month In 35-year History

Feb 24, 26 06:17 PM

North Carolina’s state-supported passenger rail service, marketed under the NC By Train brand, reached a milestone last fall. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years.