Lackawanna Cutoff: Map, Progress, Restoration

Last revised: August 24, 2024

By: Adam Burns

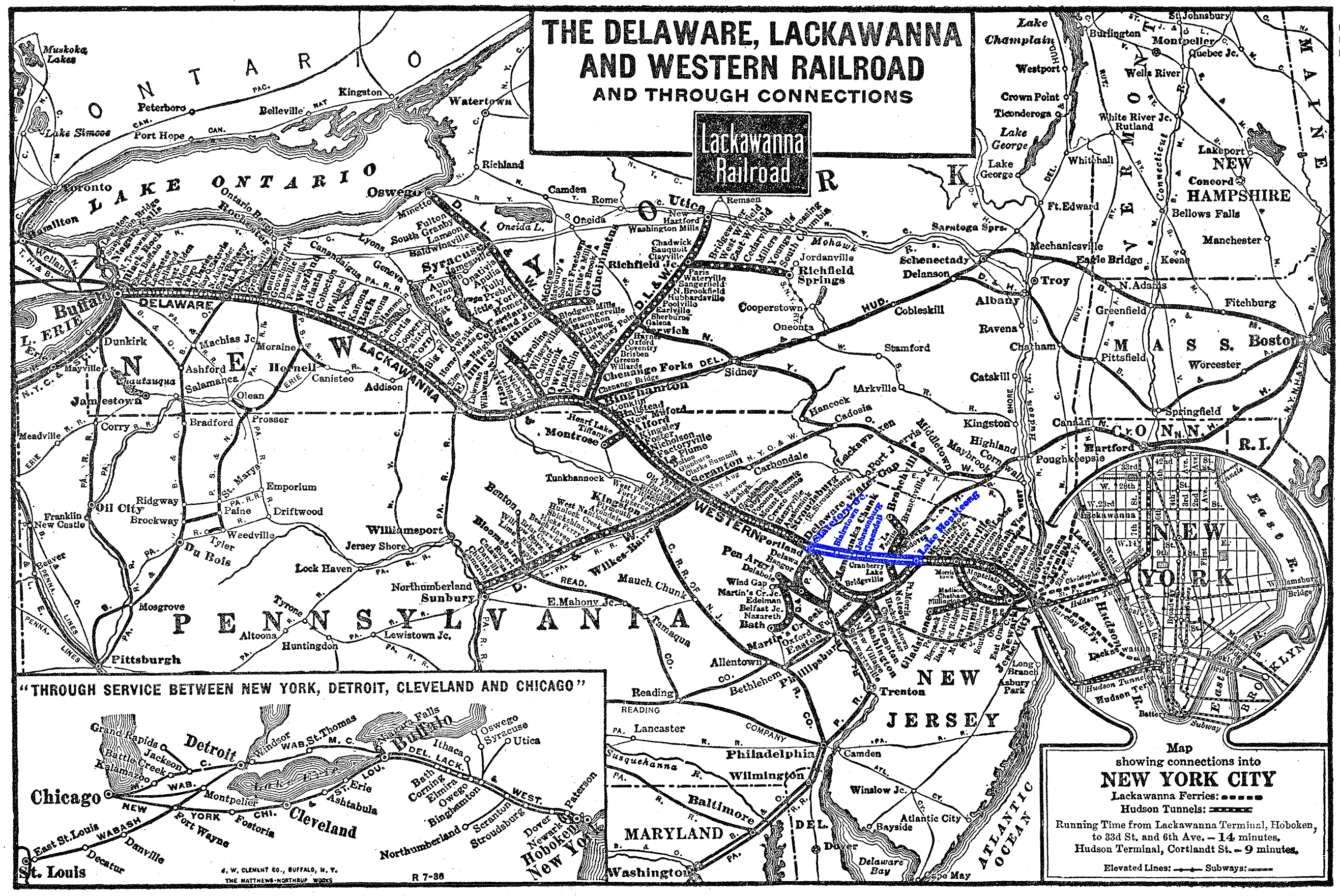

The Lackawanna Cutoff is a historic rail line in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, originally built by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) in the early 20th century.

It as one of two grand realignment projects carried out by the Lackawanna in the very early 20th century. Known for its high-speed, low-grade route, it was a significant engineering achievement, featuring large cuts, fills, and tunnels.

Working from east to west the Cutoff was built between 1908 and 1911 at a cost of $11 million. While the route was only 28.5 miles in length it eliminated more than 11 miles redundant trackage, many sharp curves, and reduced the ruling grade by more than half.

The cutoff only remained in use for 73 years before its abandonment and removal by Conrail in 1984. In the proceeding years there have been many attempts to reactive the cutoff, predominantely for passenger and commuter service.

There are few other rail corridors in such rugged terrain that offer such a superb right-of-way with few grades or curves. The property is currently owned by NJ Transit with eventual plans to restore the route to operation as a high speed commuter line.

In 2023 those plans are much closer to becoming reality when the commuter system announced plans in April to overhaul Roseville Tunnel for $32.5 million.

Photos

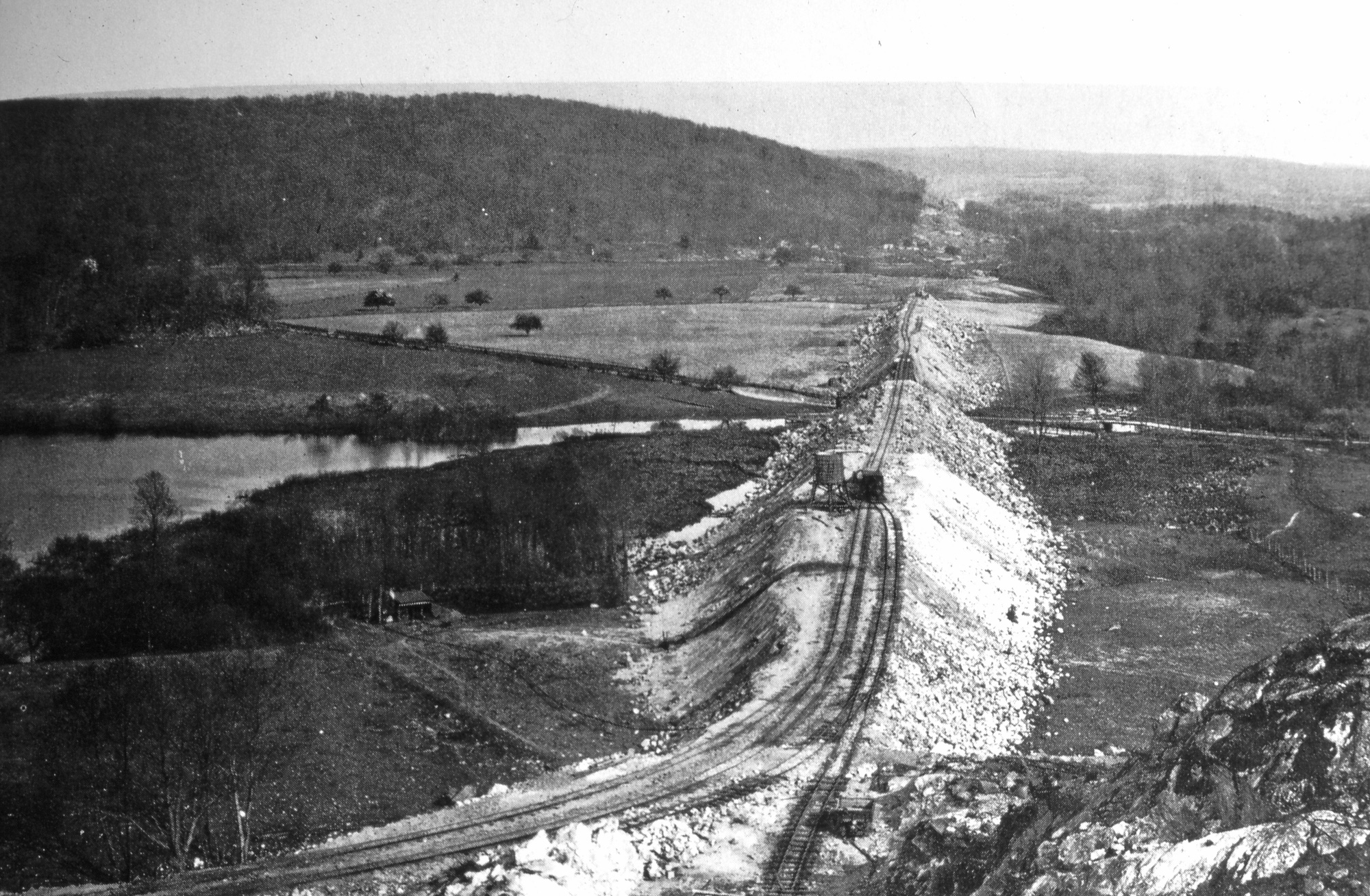

Constructing the Lackawanna Cutoff, seen here in an eastward view of Wharton Fill from the top of Roseville Tunnel in May of 1909.

Constructing the Lackawanna Cutoff, seen here in an eastward view of Wharton Fill from the top of Roseville Tunnel in May of 1909.History

The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western was one of the Northeast's most success anthracite coal lines. Its heritage can be traced back to two predecessors; the Liggetts Gap Railroad, incorporated on April 7, 1832 and the Delaware & Cobbs Gap Railroad, chartered on December 4, 1850.

The DL&W gained its name in March, 1853 when it merged with the Delaware & Cobbs Gap to form the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western.

At its peak, the DL&W operated 950 miles between Hoboken, New Jersey and Buffalo running via Scranton, Binghamton, and Elmira. The railroad also operated notable branches to Northumberland/Sunbury, Oswego, and Utica.

The current end-of-track at Lake Lackawanna, located about 4 1/4-miles west of Port Morris. The state of New Jersey is rebuilding the Lackawanna Cutoff to serve New York City-bound commuters. The line will be operated by NJ Transit.

The current end-of-track at Lake Lackawanna, located about 4 1/4-miles west of Port Morris. The state of New Jersey is rebuilding the Lackawanna Cutoff to serve New York City-bound commuters. The line will be operated by NJ Transit.Construction

Throughout most of its corporate existence, until the 1950s, was a very profitable and well-managed company thanks to the many lucrative anthracite coal mines it served. It also handled significant timber business and transported a great deal of vacationers to and from New York's many resorts in the Pocono Mountains.

Its profitabilty was never greater than at the turn of the 20th century. With the railroad overflowing in cash, William Haynes Truesdale, who became president of the DL&W on March 2, 1899, sought immediate improvements to the 950 mile railroad to increase the road's freight capacity.

He also wanted the railroad to be more competitive in the New York/New Jersey-Buffalo market in addition to alleviating a circuitous route throughout much of western New Jersey and eastern/northeastern Pennsylvania that slowed trains to only 50 mph.

To carry out the project the railroad elected to use reinforced concrete throughout , a relatively new material for that time.

The idea of the DL&W leveling and straightening its main line to Buffalo began around 1900 and was the result of its president William Haynes Truesdale,

What became known as the Lackawanna Cutoff, it was the railroad's first significant improvement project of the early 1900s.

Following the abandonment of the Lackawanna Cutoff, looking towards Roseville Tunnel in the fall of 1989 about a decade after Conrail stopped using the corridor.

Following the abandonment of the Lackawanna Cutoff, looking towards Roseville Tunnel in the fall of 1989 about a decade after Conrail stopped using the corridor.The new alignment, which replaced the "Old Road" broke away from the main line initially heading north, then west from Port Morris, New Jersey (Lake Hopatcong).

The DL&W spared no expense in straightening and leveling its main line using massive fills and deep cuts to keep the maximum ruling grade at an astounding 0.55%! Perhaps the Cutoff's most impressive feature was its bridges, which are arched designs built of reinforced concrete.

Most notable of these is Paulinskill Viaduct, one of the largest in the world at the time before Tunkhannock Viaduct was built. The bridge spans Paulins Kill in New Jersey and is more than 1,000 feet long and 100 feet high.

Map (1930)

Operation

The DL&W served many concrete plants along its network. Since it was so readily available it was an easy decision to incorporate the material into the cutoff's construction. It was also prodigously utilized on the later Nicholson-Hallstead Cutoff.

The DL&W built almost everything from concrete, from bridges and tunnels to interlocking towers, stations, and other lineside structures.

The cutoff ultimately opened for business, officially, on December 24, 1911 at a cost of more than $11 million. With no grade crossings, curves, and a ruling grade of 0.55%, the 28.45-mile double-tracked cutoff allowed trains to operate at speeds of 80 mph.

The investment underscored the company's deep commitment to revolutionizing transportation and commerce during that period. In additoin, the state-of-the-art rail line was opened to wide acclaim and heralded a new epoch of innovation in the realm of railroads and transportation.

The innovative use of reinforced concrete for the construction of bridges and viaducts marked the Cutoff as a trailblazer. This pioneering engineering choice significantly increased the infrastructure’s durability and resilience, ensuring the Cutoff remained unscathed even after a century of its initiation.

The Cutoff's peak years of operation were arguably from the 1920s through to the late 1940s. During these decades, the Cutoff ferried millions of tons of freight and countless passengers with remarkable efficiency and speed.

Abandonment

The cutoff remained in use through the DL&W and Erie Lackawanna (1960) eras. Passenger service on the line ended in 1971 and most of the remaining freight trains had been transferred to the former Erie main line after the EL merger.

Interestingly, the decision to transfer trains off the corridor was largely one of opposing management styles. When the Erie Lackawanna merger occurred in 1960, most of the company's top officials came over from the Erie while DL&W's management team was given few notable leadership roles.

By the time Conrail assumed control of the route (April 1, 1976) virtually no online traffic remained and the railroad made plans to abandon the route, despite its level grade. In 1984 the rails were pulled although an effort to preserve the right-of-way for future commuter use in 1989 saved it from an uncertain future.

Over the past few decades, however, interest in the Lackawanna Cutoff has seen a resurgence. Multiple campaigns and movements have rallied to restore this historical symbol, resituating it within contemporary discourses of transportation and historical preservation.

Since that time, both Pennsylvania and New Jersey have slowly worked to complete the necessary paperwork to begin the line's reconstruction. This effort culminated with the reconstruction of the first 7.3 miles between Andover and Port Morris Junction, New Jersey in 2013.

Seen here is the massive Pequest Fill under construction, near Tranquility, New Jersey in the summer of 1911.

Seen here is the massive Pequest Fill under construction, near Tranquility, New Jersey in the summer of 1911.2022 Restoration

Following almost another decade of little activity, in an announcement made public in April, 2022 NJ Transit stated that it plannned to invested $32.5 million in repairing and overhauling the 1,024-foot Roseville Tunnel between Port Morris and Andover.

The project is part of a larger effort for NJ Transit and Amtrak to finally expand passenger service directly to Scranton, Pennsylvania.

To do so, the Lackawanna Cutoff (Port Morris - Slateford Junction, Pennsylvania) must be restored, which can then utilize short line Delaware-Lackawanna Railroad's trackage (ex-Lackawanna) into Scranton.

This is the closest the famous cutoff has been yet to finally seeing trains return after nearly 40 years of silence. It appears with the tunnel's restoration it will finally become reality.

Overall, the Lackawanna Cutoff is much more than just a stretch of railroad. It is a living testament to a bygone era of innovation, determination and engineering prowess, embedding deep in the heart of the American railroad narrative. With current efforts to restore the line, the future may yet see the rebirth of this grand piece of history.

Recent Articles

-

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad.