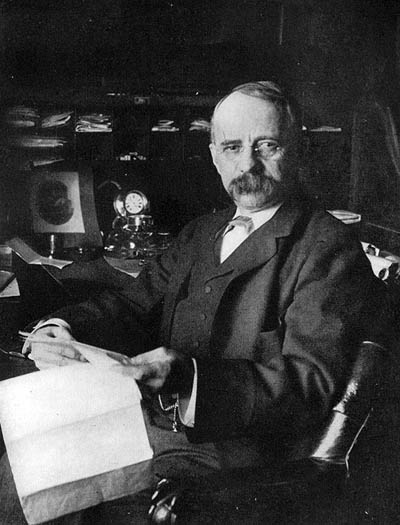

Edward H. Harriman (Railroad): Facts, Robber Baron, Biography

Last revised: July 25, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Edward H. Harriman was an American railroad executive and financier, known for reorganizing and consolidating various failing railway systems into well-managed, profitable enterprises.

Born in 1848, Harriman began his career as a stockbroker and later became the director of the Union Pacific Railroad, turning it into a highly efficient business.

Harriman's aggressive business tactics and significant influence on the American railway system earned him a reputation as a ruthless "robber baron." He died in 1909.

Because of his immense success in managing,

reviving, and controlling railroads Edward H. Harriman (or, E.H. Harriman) has often been

regarded as another of the ruthless tycoons.

However, much like James Hill, Harriman actually took great interest in the railroads he oversaw and found great reward and turning a rundown line into a profitable operation.

Perhaps the best example is Union Pacific which was bankrupt following 1893's Financial Panic. However, under Harriman's leadership the UP became a profitable operation and prospered. Much of the railroad's foundation was laid during his tenure and the company may be another historical footnote without his efforts.

While he is best known for his time at UP he also controlled several other noteworthy railroads including Southern Pacific, Illinois Central, and Central of Georgia Railway.

His estate went beyond the railroad industry and included the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and Wells Fargo Express Company. It is said he net worth ranged from $150 million to $200 million, which was left to his wife Mary Williamson following his death.

Early Life

Edward Henry Harriman, more commonly known as E.H. Harriman, was born on February 25, 1848, into a middle-class family in Hempstead, New York. His father was a Episcopal minister, which shaped the early part of Harriman's life significantly.

In his personal life, Harriman married Mary Williamson Averell, and together they had six children. Among them were Averell Harriman, a future state governor, and Mary Harriman Rumsey, who became a philanthropist.

Never one who much liked school he left his studies at only the age of 14 to pursue a career on Wall Street along with the help of his uncle, Oliver Harriman.

Harriman's footsteps into the world of business investments were uncharted, yet confidently made. Despite the lack of formal education, he became a broker in Wall Street at the age of 19.

By 22, he had become a member of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and proved so adept he started his own brokerage firm.

In 1879 he married Mary Williamson Averell at the age of 31 and thus became quite interested in railroads due to his father-in-law, William Averell being president of the Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain Railroad.

Railroads

In 1881 Harriman became interested in railroad securities and acquired bonds of the Chicago, St. Louis & New Orleans. With available capital from this move he purchased the bankrupt Lake Ontario Southern Railway in 1882 and reorganized it as the Sodus Bay & Southern Railroad.

An A-B-B-A set of Union Pacific covered wagons ready to depart from an unknown location in June of 1968. Mac Owen photo.

An A-B-B-A set of Union Pacific covered wagons ready to depart from an unknown location in June of 1968. Mac Owen photo.This railroad began as the Sodus Bay & Southern Railroad of 1873 connecting Sodus Point on Lake Ontario with Stanley, New York to the south (a distance of about 40 miles).

The line was never profitable until Harriman gained control of the property quickly turning it around. By 1884 he had sold the line to the Northern Central Railway, then a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

At A Glance

Orlando Harriman, Sr. (father) Cornelia Neilson (mother) | |

Union Pacific Southern Pacific Saint Joseph and Grand Island Railroad Illinois Central Central of Georgia Railway | |

Pacific Mail Steamship Company Wells Fargo Express Company |

In 1883 he took a significant step in the industry hierarchy when he was elected to the Illinois Central's board of directors.

Under Harriman's direction the railroad expanded west and north reaching (via branch lines) Madison and Dodgeville, Wisconsin along with Cedar Rapids, Iowa; Omaha, Nebraska; and Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Later it reached cities like Indianapolis, Birmingham and Fulton, Kentucky. He was also able to guide the IC through the Panic of 1893 without it falling into bankruptcy.

Union Pacific

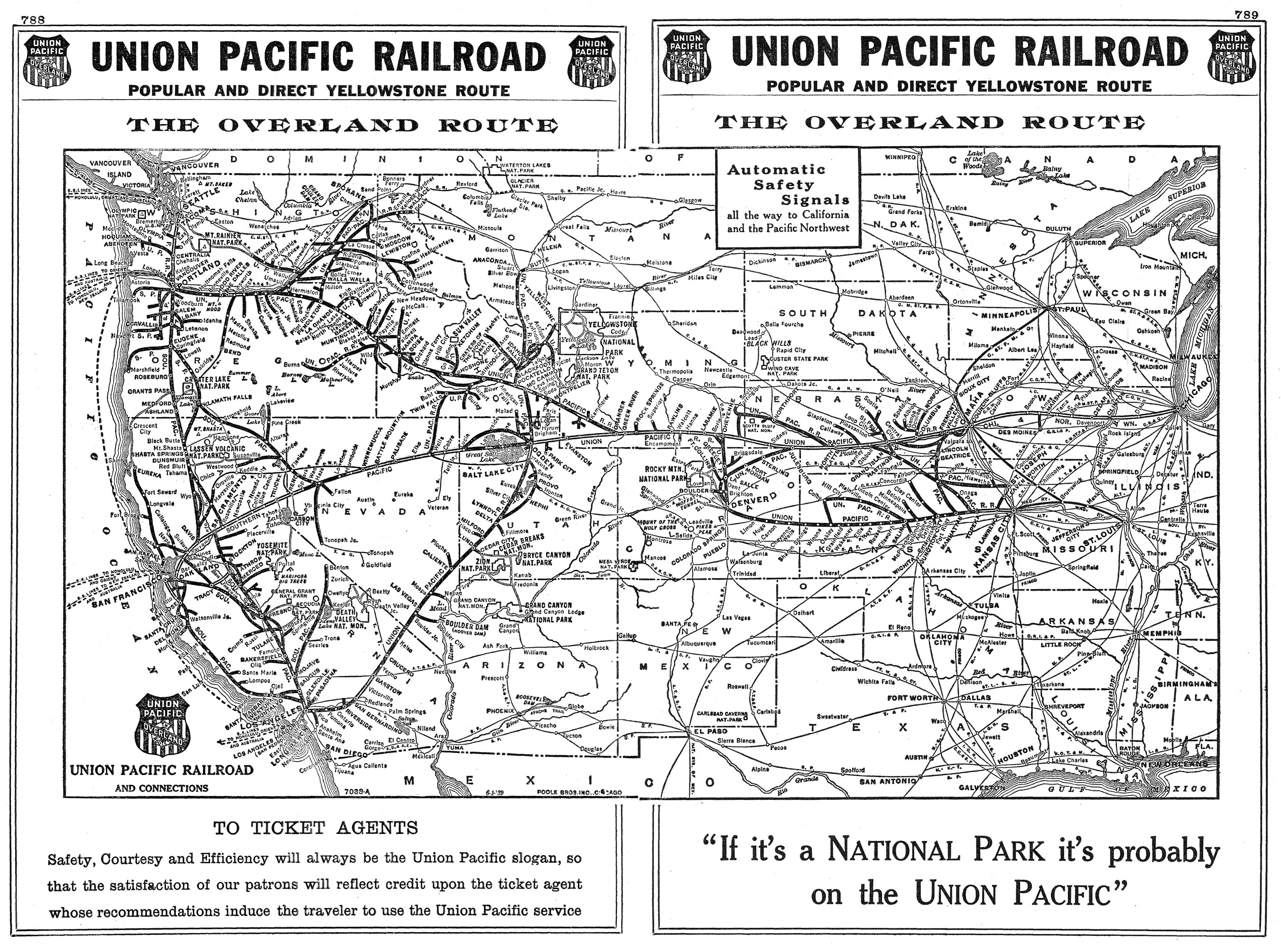

In 1897, Harriman purchased a leading stake in the struggling Union Pacific, which was in financial ruin after the Panic of 1893. Even at that time the company was well known as being the eastern component of the first Transcontinental Railroad.

Despite the UP's teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, Harriman perceived it as an opportunity to revamp the industry and embarked on a significant rebuilding project.

Harriman quickly set to changing the culture at UP, restructuring its heavy debt, and pouring millions of dollars into upgrading the railroad's property.

Under Harriman, Union Pacific saw its main line between Omaha, Nebraska and Granger, Wyoming entirely double-tracked, a more efficient route scaling Sherman Hill (located in Wyoming), significant line relocations to improve grades and curves, and an updated, automatic signaling system.

Furthermore, he improved the alignments and upgraded stations, making them more passenger-friendly. This resulted in the increased reliability and speed of the Union Pacific trains, which significantly enhanced the line's profitability.

It was during Harriman's tenure that the Union Pacific became its own transcontinental railroad, connecting to Los Angeles via Ogden, Utah in 1907.

A primary reason for Harriman's success was his call for streamlining operations and standardization, notably with a company's fleet of freight and passenger cars.

Beyond infrastructure, Harriman also focused on improving the company’s management. He introduced a centralized system and eliminated corruption at UP. This instilled a sense of professionalism which was subsequently reflected in the company's smooth operations. It has remained well managed and maintained ever since.

Southern Pacific

Arguably Harriman's most notable deal came when he acquired Southern Pacific in 1901. He efficiently merged it with Union Pacific (although both companies remained separate operations), creating an efficient and modern railroad network in the west.

Harriman's involvement with the Southern Pacific was marked by vast capital improvement projects similar to the Union Pacific. Under his supervision, Southern Pacific experienced advancements in communications using wireless telegraph, installments of block signals for safety, and grade reductions.

He improved the mainline tracks and significantly expanded the railroad's network. He also invested in the construction of the Lucin Cutoff across the Great Salt Lake, which slashed the route by 43 miles. These upgrades made Southern Pacific a lucrative railroad operation in the Western United States.

Recognizing the importance of freight business, Harriman implemented policies that increased the load capacity of freight cars and the speed of operations. This boosted the profitability of both Southern Pacific and Union Pacific as they could cater to the growing markets in western states more efficiently.

By 1901, Harriman had quite an empire of railroads in the west including, along with the Union Pacific, the Southern Pacific and Central Pacific. However, in 1904 he was sued by President Theodore Roosevelt and the Supreme Court forced Harriman to break up his empire.

Other Acquisitions

However, still under the management of the Union Pacific after this incident, he moved eastward and took over management of the Chicago & Alton, Central of Georgia, and even the Erie Railroad in 1908.

The Erie would be Harriman's final management as a railroad magnate as he passed away in September of 1909. His reputation as a ruthless railroad baron was mostly based on conjecture by the general public as they only saw the end result and millions of dollars he earned for managing so many companies.

In truth, he was anything but as he worked tirelessly to maximize a railroad's efficiency and make it as profitable as possible, taking great pride in doing so.

Harriman remains a legendary figure at Union Pacific today as the railroad's primary dispatching center in Omaha is named directly after him, the Union Pacific Harriman Dispatch Center.

Net Worth

Over the course of his career, Edward Harriman accumulated vast wealth. At the time of his death in 1909, his estate was valued at approximately $200 million. His wealth was largely attributed to his majority shareholdings in the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads.

Legacy

Harriman died on September 9, 1909. His vast fortune was divided amongst his wife and children. His son, Averell Harriman, stepped into his father's shoes and continued to manage the railroads.

The legacy left by Harriman in America's railroad industry is undeniably impressive. His vision and unwavering dedication to the advancement of the railroad networks has left an indelible mark on America’s transportation infrastructure.

His investments and improvements in the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific not only turned around the collapsing companies but also contributed to the development of the West. His efforts to streamline operations and focus on customer service have had far-reaching implications in the industry.

Harriman's work impacted not only the business of railroads but also labor policies across the country. His management practices resulted in an improvement of employee rights, with workers benefiting from his introduction of standardized hours and better pay.

His willingness to invest in infrastructure development went beyond pure business reasons, it demonstrated his interest in science and engineering. He contributed to numerous scientific expeditions and funded research that has increased our understanding of the natural world.

Beyond his business endeavors, Harriman was known for his many philanthropic activities. He funded the establishment of the Harriman Research Laboratory, which became a leading institute for studying blood diseases.

Despite his achievements, Harriman's life was not without controversy. His aggressive acquisition of railroads earned him the title of "railroad baron," and he was often criticized for his monopolistic tendencies.

At the peak of his power, Harriman controlled about 60,000 miles of railroads in the U.S., earning him the scrutiny of President Theodore Roosevelt. This resulted in regulation changes that restricted monopoly power in the railroad industry.

In his later years, Harriman became involved in philanthropy. His contributions in the field of education and health were significant, with substantial donations to Columbia University and other higher education institutions. His values and business mindset have been a source of inspiration for future generations of entrepreneurs and business leaders.

Today, Edward H. Harriman is remembered as one of the most important figures in American railroad history. His contributions to transforming Union Pacific and Southern Pacific into highly efficient and profitable operations, and his commitment to improve and expand railroads in the U.S. have cemented his place in American history.

The Sweedler Preserve at Lick Brook in Ithaca, New York was once part of Harriman's vast empire, and it still pays homage to his legacy with part of his name. Harriman State Park, one of the nation's largest parks, was developed from land Harriman gave to the state of New York in memory of his wife.

Harriman's legacy also continues through his descendants. His son Averell Harriman served as U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President Harry S. Truman, and under President John F. Kennedy, he served as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs.

Edward Harriman truly transformed the American railroad industry, turning rickety and inefficient railroads into an efficient, superpower transportation system that played a pivotal role in modernizing the U.S. economy in the late 19th century.

Harriman not only recognized the importance of a robust railway system but also foresaw the enormous opportunities it would bring to the American West. His investments and work play a crucial part in the successful growth of the western U.S.

Despite his humble upbringing and lack of formal education, Harriman demonstrated superior management skill and business acumen. He was a visionary leader who was able to perceive great opportunities in seemingly dire situations.

His ruthless business tactics earned him a fair share of critics and enemies. However, there is no denying that Harriman reshaped the American railroad industry and laid the foundations for the modern infrastructure that is so critical to the U.S. economy.

Declared as one of the richest persons in the U.S. during his time, Harriman's name is often mentioned alongside fellow industrial magnates of the era like Rockefeller and Carnegie. His influence on business and industry was profound, and his legacy continues to be felt today.

Edward H. Harriman exhibited a unique blend of foresight, business ingenuity, and unwavering persistence. These qualities not only led to his phenomenal success but also served to shape the American railroad industry.

Harriman's insights and strategies, particularly in the development of the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific, are still relevant today. Whether in terms of railroad design, operations, labor policies, or adoption of advanced technology, his vision continues to inspire.

In conclusion, Edward H. Harriman's determination, vision, and leadership epitomize the "American dream." His legacy continues to shape and inspire the world, enriching the annals of American railroads for generations to come.

From Hempstead to Wall Street, from Union Pacific to Southern Pacific, Harriman's life journey is an enduring journey of dreams, determination, and success. His remarkable story reflects the heights that the human spirit can reach and the profound impact that one individual can have on the world.

Sources

- Murray, Tom. Illinois Central. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2006.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Solomon, Brian. Southern Pacific Railroad. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2007.

- Welsh, Joe and Holland, Kevin. Union Pacific Railroad. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2009.

Recent Articles

-

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad.