Steam Locomotive "Firebox": Design, Purpose, Photos

Last revised: February 22, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Steam locomotives, an iconic symbol of the Industrial Revolution, played a vital role in revolutionizing transportation and shaping the modern world.

Central to their functionality was the firebox—a critical component responsible for generating the necessary heat and steam to not only propel these mighty machines forward but also pull incredible tonnage.

This essay explores the design, operation, and historical significance of the firebox, highlighting its pivotal role in the development of locomotive technology and the advancement of society.

Photos

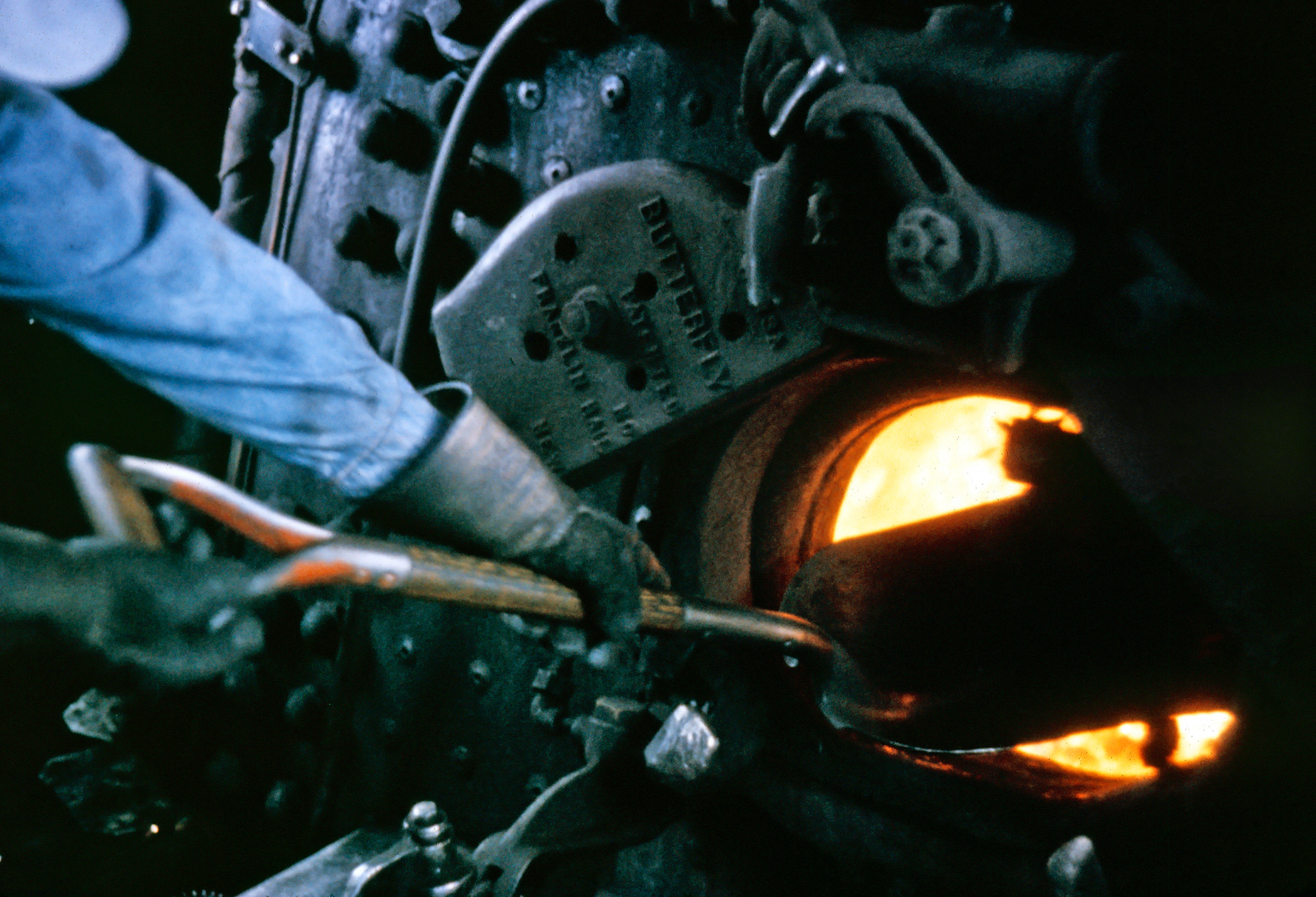

A fireman, an extinct craft in modern railroading, shovels coal into the firebox of Great Western Railway Of Colorado 2-10-0 #90 in the fall of 1960. A.C. Kalmbach photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A fireman, an extinct craft in modern railroading, shovels coal into the firebox of Great Western Railway Of Colorado 2-10-0 #90 in the fall of 1960. A.C. Kalmbach photo. American-Rails.com collection.Overview

The steam locomotive, an engineering marvel of its time, brought about a revolution in transportation during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Behind its incredible power and performance lay the heart of an iron horse - the firebox.

This device was a pivotal part of the steam locomotive, responsible for creating the steam that powered the engine and enabled the locomotive to travel vast distances, carrying both passengers and freight.

Design

The firebox was a carefully crafted and strategically positioned chamber where the combustion of fuel occurred. Typically located at the rear of the locomotive's boiler, the firebox was enclosed by a sturdy steel shell and also featured firebrick, or refractory materials, to withstand extreme temperatures.

This design facilitated the efficient and safe burning of fuel, often coal, which was readily available during the height of the Industrial Revolution.

The shape and size of the firebox played a crucial role in determining the locomotive's overall performance. Engineers, in conjunction with the fireman, had to strike a balance between maximizing heat transfer to the boiler's water, ensuring a steady supply of steam, and minimizing heat loss through the firebox walls.

This led to various firebox designs; the four most common included the Belpaire, Wootten, crown bar, and radial-stayed (wagon top), each tailored to suit specific locomotive models and requirements.

The standard firebox was a rectangular box located at the back of the boiler, built of iron or steel in the United States while British variants were typically built from copper.

A space was left between the firebox and boiler's interior wall which formed a water jacket known as the "water leg." While steam pressure was capable of separating the water leg, staybolts were installed to prevent this.

The entire firebox assembly rested on the foundation ring; its floor consisted of the grate, where the actual fire was located, and beneath this the ash pan which captured spent coal or wood ashes.

The front of the firebox could not be seen from the cab as it faced the boiler's interior. It consisted partially of the back tube sheet (which held the fire tubes that traveled through the boiler interior) and throat sheet, located between the tube sheet's bottom and front of the foundation ring. The back of the firebox faced the cab and featured the fire door.

Interestingly, the steel which comprised the firebox could not withstand the intense heat of the fire; it would soften at 600 to 700 degrees Fahrenheit, while the fire could reach 1,500 - 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Only the water, at around 390 degrees Fahrenheit, prevented the steel's softening, as well as potential collapse from the steam pressure.

The firebox was one of the most dangerous components of a steam locomotive. As Brian Solomon notes in his book, "Working On The Railroad," if water in the boiler dropped below the top of the firebox (crown sheet), a catastrophic explosion was imminent.

Such an unfortunate incident was always on the crew's mind. It was the fireman's job to ensure the water sight glass was clean and properly functioning so the crew always knew exactly how much water was in the boiler.

Operation

The operation of the firebox was a delicate process that required the expertise of skilled firemen. A steam locomotive, itself, is often a stubborn and uncooperative machine. Once the engine was ready for service, firemen would carefully load the firebox with coal and ignite it, creating a fiercely burning fire.

Firing a cold, coal-fueled locomotive could sometimes be a tricky and difficult proposition, especially during the winter months. Doing so typically required throwing a fuel-soaked rag (usually drenched in either paraffin, petrol, or lubrication oil) into the firebox and then placing kindling (scrap wood) on top of the coal to keep the fire lit until the latter ignited.

The fire door would then be immediately closed to allow the fire's intensity to grow. If the coal remained lit, the fireman would next doublecheck water levels and perform a "blowdown," which removed any mineral sediments in the boiler water that had built up around the sides of the firebox (known as the mud ring).

These particulates can cause a real issue with providing proper steaming, build up in the boiler if not removed, and potentially damage vital engine components (such as the piston or piston rod).

Tom Morrison's excellent book, "The American Steam Locomotive In The Twentieth Century," provides more details regarding firing a locomotive:

"The fireman or roundhouse crew lite the fire in a locomotive firebox with layers of coal, kindling and oily rages spread evenly over the grate. A necessary preliminary was to insure that the boiler contained enough water to cover the crown sheet.

Over a period of hours the fireman would build this into an evenly burning fire bed 6 to 8 inches thick. This filled the cab with smoke until the heat of the fire boiled water and produced enough steam pressure to use the blower to draw smoke through the fire tubes and out through the stack. The fireman continued to build the fire until nearly full boiler pressure had been reached, at which point the locomotive was read to go about its business."

The fire's intensity was regulated to maintain a constant temperature, allowing for a steady production of steam. Properly balancing the combustion rate was crucial to avoid overfiring, which could damage the firebox and waste valuable fuel.

The steam generated in the firebox would rise through flues and enter the boiler, heating the water to produce high-pressure steam. This steam would then travel through the cylinders, driving the locomotive's wheels and providing the mechanical power necessary for motion.

The fireman is a long-lost artform, only occasionally still found at heritage railroads, Union Pacific (which maintains two enormous locomotives for public display, 4-8-4 #844 and 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4014), and a few short lines.

Before the advent of modern stokers, which provided continuous fuel to the firebox and ended the fire door's opening from potentially allowing cold air to reach the back tube sheet and causing uneven expansion and contraction, which ultimately affected steam pressure.

A seasoned fireman knew precisely when to add fuel, use of the dampers (to help control air flow into the fire), let off steam (if necessary), use of the injector (to control steam pressure), and sometimes even briefly opening the firebox door which would burn off the volatiles and reduce smoke.

A good fireman and engineer worked as a team and ensured a contrary steam locomotive operated at peak performance. It is said that every engine had its own personality, even those of the same class built largely to the same specifications.

Super Power Designs

Early steam locomotives, such as the 4-4-0 "American" type, always featured the firebox situated between the main driving wheels. However, as trains became heavier, larger locomotives were needed; as a result, trailing trucks were added to support larger fireboxes.

This led to designs like the 2-6-2, 2-8-2, 4-8-4, etc. In his book, "The Steam Locomotive Energy Story," author Walter Simpson notes the need for more powerful locomotives gave way to "Super Power" designs, the first of which was the 2-8-4 "Berkshire" developed by the Lima Locomotive Works and New York Central in 1925.

The defining characteristic of these designs was a larger firebox featuring a 100 square foot coal grate, which necessitated a larger four-wheel trailing truck. Other characteristics of a "Super Power" locomotive included:

- Type E Superheater

- High Efficiency Feedwater Heater

- Higher Boiler Pressure

- Front End Throttle

- Large Driving Wheels To Permit Effective Counterbalancing

Historical Significance

The introduction and widespread adoption of the steam locomotive during the 19th century marked a pivotal moment in history.

Steam locomotives revolutionized transportation, enabling faster and more efficient movement of goods and people across vast distances. The steam locomotive firebox, with its ability to convert the energy locked within coal into mechanical work, was an essential part of this technological breakthrough.

The construction and continuous improvement of firebox designs also played a vital role in the advancement of engineering and metallurgical sciences.

Engineers and inventors constantly sought ways to optimize the firebox's efficiency, leading to the development of more powerful locomotives capable of handling heavier loads and achieving higher speeds.

Before the advent of mechanical stokers, they also derived ways to prevent cold air from reaching the tube sheet; one method was a steel deflector plate over the fire door inside the firebox, which forced cold air down into the bed of the fire, preventing it from reaching the tube sheet.

Three individuals are credited with this invention; in Britain Matthew Kirtley and Charles Markham of the Midland Railway developed such a device in 1859 while William Smith, Superintendent of Motive Power and Machinery at the Chicago & North Western is recognized in America for designing a similar device in 1893.

The mechanical stoker was a vast improvement in steam locomotive development; a fireman was no longer required to manually shovel coal into the firebox and the boiler was provided a constant and consistent flow of fuel. Mr. Morrison's book notes the first such stokers were not used in railroading; they were simple chain grate used in stationary steam plants.

The first company credited with developing a mechanical stoker for steam locomotives was the J.H. Day & Company in 1900/1901. Their "Kincaid" steam-powered locomotive stoker featured a pair of spiral "screws" that drew coal from a hopper, moved it to a trough where then a steam-driven plunger pushed it through the fire door and into the firebox.

The device still required a fireman to keep the hopper filled and it was soon discovered the Kincaid could not meet coaling demands; the device only provided about 3,000 lbs of coal per hour when a typical steam locomotive of that time consumed about 9,200 lbs per hour.

Nevertheless, it was a breakthrough technology that was soon improved upon. In the Railroad Gazette's July 8, 1904 edition in a discussion on automatic stokers by the American Railway Master Mechanics' Association, the Great Northern is credited with operating the first in 1902, followed by the Chesapeake & Ohio in 1904.

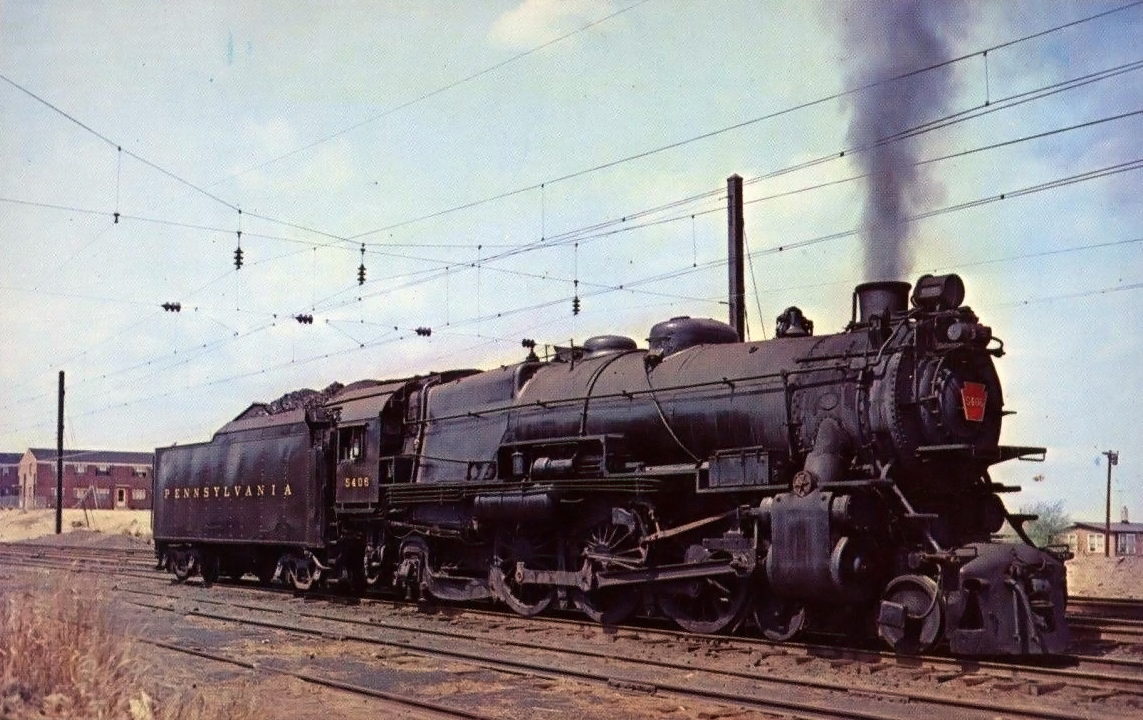

Pennsylvania 4-6-2 #5406 (K-4s) with its large Belpaire firebox, waits for a GG-1 powered consist to arrive at South Amboy, New Jersey on the New York & Long Branch during April of 1956. Don Wood photo.

Pennsylvania 4-6-2 #5406 (K-4s) with its large Belpaire firebox, waits for a GG-1 powered consist to arrive at South Amboy, New Jersey on the New York & Long Branch during April of 1956. Don Wood photo.Conclusion

The firebox's design, operation, and historical significance demonstrate the ingenuity of the engineers and firemen who harnessed the power of steam to drive progress.

While steam locomotives have largely been replaced by more advanced technologies today, the legacy of the steam locomotive firebox remains a testament to the human spirit of innovation and exploration that continues to drive us forward in the pursuit of new frontiers.

Sources

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Morrison, Tom. American Steam Locomotive In The Twentieth Century. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019.

- Simpson, Walter. Steam Locomotive Energy Story, The. New York: American University Presses, 2021.

- Solomon, Brian. Working On The Railroad. St. Paul: MBI Publishing Company, 2006.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.