Erie Lackawanna Railway: Map, Roster, History, Logo

Last revised: October 11, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Erie Lackawanna Railway was created in 1960, the result of a

marriage between the Erie Railroad and Delaware, Lackawanna &

Western as a means to cut costs and better streamline operations.

It’s interesting that despite the company lasting only 16 years, EL remains a greatly discussed subject today and admired by those who enjoy all aspects of railroading.

It was one of the earliest mega-mergers carried out across the country to achieve greater efficiency in the face of stiff governmental regulations and falling traffic.

While the new EL enjoyed some savings it was never a strong carrier facing problems both within, and outside of its control.

Following the 1968 Penn Central disaster, EL dealt with one issue after another, most notably the severe flooding from Hurricane Agnes which forced it into bankruptcy.

It initially opted out of Conrail but eventually decided otherwise a few years later. Today, large components of its network east of Ohio are still in use. However, west of Marion, Ohio its Chicago main line has returned to local farmers and property owners.

A handsome set of Erie Lackawanna covered wagons, led by F7A #6111, layover in Binghamton, New York during February of 1966. Also note the FB-1. American-Rails.com collection.

A handsome set of Erie Lackawanna covered wagons, led by F7A #6111, layover in Binghamton, New York during February of 1966. Also note the FB-1. American-Rails.com collection.History

What eventually became Erie Lackawanna can trace its heritage back to the 1950s when two of the Northeast's competing railroads realized the future looked bleak; the euphoria of record traffic during World War II was quickly dashed by sharp declines afterwards.

The historically successful Delaware, Lackawanna & Western, which had never dealt with bankruptcy after more than a century of service, lost nearly $1 million in 1955 while the Erie tried innovative ways to curb losses by encouraging industrial development along its property and launching new trailer-on-flatcar service (TOFC) during July of 1954.

At A Glance

Hoboken - Newark, New Jersey - Scranton, Pennsylvania - Binghamton, New York Jersey City - Paterson, New Jersey - Port Jervis, New York - Susquehanna - Binghamton Binghamton - Hornell - Buffalo, New York Binghamton - Utica, New York Binghamton - Syracuse - Oswego, New York Lake Hopatcong - Slateford Junction, New Jersey (Lackawanna Cutoff) Scranton - Northumberland/Sunbury, Pennsylvania Corning, New York - Newberry Junction, Pennsylvania Jamestown - Buffalo Port Jervis - Campbell Hall/Maybrook, New York - Suffern, New Jersey Hornell - Salamanca, New York - Youngstown, Ohio - Cleveland Youngstown - Marion, Lima, Ohio - Huntington, Indiana - Hammond, Indiana - Chicago Jersey City - Chicago (main line) | |

Erie Lackawanna PA-1 #856, still wearing its Erie colors, is seen here in Port Jervis, New York on September 6, 1964. Robert Gayer photo.

Erie Lackawanna PA-1 #856, still wearing its Erie colors, is seen here in Port Jervis, New York on September 6, 1964. Robert Gayer photo.The Erie was the fourth way to Chicago, competing in the hotly-contested market alongside the New York Central, Pennsylvania, and Baltimore & Ohio running via Binghamton, Salamanca, Marion, and Rochester.

Its routing was somewhat slower than its competitors but featured a high and wide, double-tracked main line with arguably the best engineered route across Indiana.

According to H. Roger Grant's authoritative title, "Erie Lackawanna: Death Of An American Railroad, 1938-1992," executive John Barringer III noted during the 1920s that, "No other railroad into Chicago has as easy grades as the Erie route," a sentiment echoed by others.

However, the Erie was also hampered with heavy debt throughout much of its history due to four bankruptcies dating back to the Civil War era (1861, 1878, 1893, and 1938). The road to merger began in 1954 when the Erie launched informal talks with the Lackawanna.

In this early Erie Lackawanna scene, SW9 #446 (ex-Delaware, Lackawanna & Western #551) and #443 (ex-Delaware, Lackawanna & Western #463) layover at the former DL&W's shops and roundhouse in Scranton, Pennsylvania during the early 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

In this early Erie Lackawanna scene, SW9 #446 (ex-Delaware, Lackawanna & Western #551) and #443 (ex-Delaware, Lackawanna & Western #463) layover at the former DL&W's shops and roundhouse in Scranton, Pennsylvania during the early 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.In the meantime, to cut losses they voluntarily initiated joint operations in various locations; on October 13, 1956 the Erie began using Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal for commuter services, completing the closure of its Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City on December 12, 1958.

In addition, beginning in 1957 the two shared trackage between Binghamton and Gibson, New York via the Erie's main line.

These moves were nearly unheard of at the time, long before the modern merger movement. On September 10, 1956 studies were launched regarding a formal merger between the Erie, DL&W, and Delaware & Hudson. The inclusion of the D&H would have been a significant boon for the new railroad.

For fiscal year 1955, its net income was more than $9 million, greater than the Erie and Lackawanna's combined (the DL&W actually lost near $1 million that year) while operating only a fraction of the trackage.

Erie Lackawanna slug B66, formerly DRS 4-4-1500 #1105 rebuilt by the shops in Hornell, New York, is seen here in Secaucus, New Jersey, circa 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna slug B66, formerly DRS 4-4-1500 #1105 rebuilt by the shops in Hornell, New York, is seen here in Secaucus, New Jersey, circa 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.The D&H would have also provided new markets through northern New York and Montreal, Quebec. On April 13, 1959 "The Bridge Line" disappointingly dropped out of discussions but the other two roads forged ahead, in part due to the country's deepening recession.

During the entire process they had relied on the consulting firm Wyer, Dick & Company to prepare studies regarding cost savings and potential earnings. The idea of a union between the two roads seemed logical.

The Erie provided the coveted western connection to Chicago while the two roads could merge duplicate facilities and shed redundant trackage along their territories east of Buffalo.

Erie Lackawanna F3A #8411 leads a passenger special out of Hoboken Terminal on June 8, 1963. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna F3A #8411 leads a passenger special out of Hoboken Terminal on June 8, 1963. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Wyer, Dick believed the new company could generate $16.6 million in annual savings, albeit this was dependent upon carrying out infrastructure improvements and/or acquiring new rolling stock/locomotives (i.e., capital expenditures). In addition, net income would rise from $2.8 million in the merger's first year to $24.1 million after five years.

The D&H setback was unfortunate in other ways; not only would it have provided for a stronger overall company but the railroad also carried just one outstanding bond. By comparison, the Erie had seven and the once-vaunted Lackawanna, fifteen.

Logo

The Erie Lackawanna's classic logo was a simple but very creative design using aspects of both predecessor companies. It was created by former Erie fireman Truman Knight, from Stow, Ohio, who worked the Kent Division.

The base concept was his company's old diamond logo but with "Erie" removed from the center. In its place he used a stylized "E" with the top arms slightly disconnected so that it also formed an "L."

Finally, the logo was adorned in Lackawanna's classic maroon instead of Erie's yellow and black, thus incorporating both predecessors into the new design.

The emblem was widely praised by top management and well-liked by employees. It was the winning choice of close to 2,500 entries submitted in a contest to create a new herald; Knight was given twenty shares of common stock in the new EL. Historically, his design will live on as one of the industry's classic logos.

Erie Lackawanna GP35 #2569 appears to be tied down with its train at the west of Kent Yard in Kent, Ohio during May, 1975. Jerry Custer photo.

Erie Lackawanna GP35 #2569 appears to be tied down with its train at the west of Kent Yard in Kent, Ohio during May, 1975. Jerry Custer photo.Formation

Looking back, the D&H may have also helped save the EL from its future bankruptcy, or at the very least enabled its reorganization. Over the next year the process worked its way forward until the Interstate Commerce Commission formally approved the union on September 13, 1960.

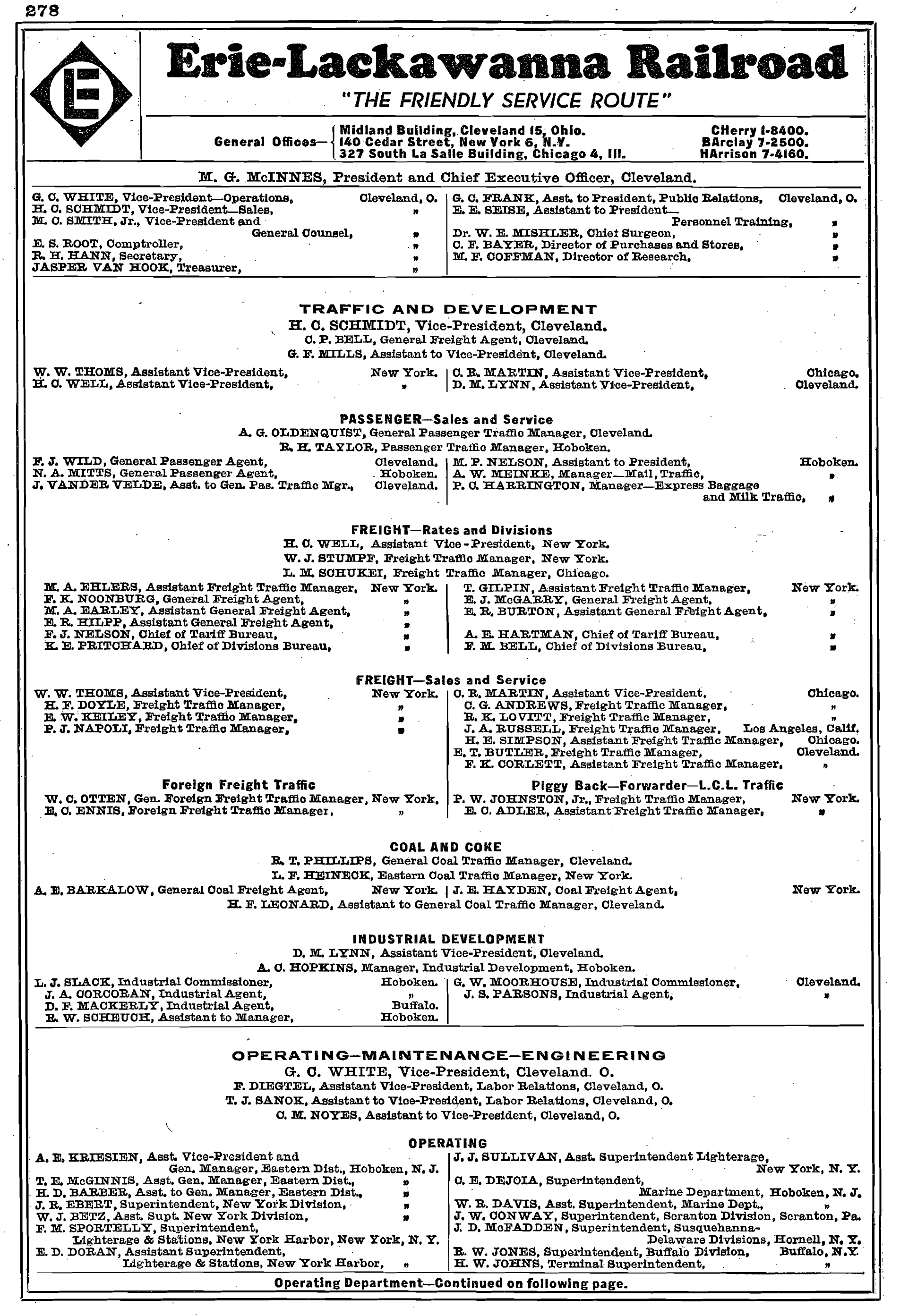

The new Erie-Lackawanna Railroad (EL) officially began operations on October 17, 1960 with an entire network of 3,031 miles. In 1963 the company dropped the hyphen and became simply the Erie Lackawanna Railroad.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #830 leads the "Lackawanna Limited" at Wharton, New Jersey on May 19, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #830 leads the "Lackawanna Limited" at Wharton, New Jersey on May 19, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.From the very start, EL ran into issues both of its own doing and outside its control. The long-seated rivalry of the two predecessors emerged when Lackawanna's officers were largely ignored in favor of the Erie's.

The issue here was not only one of favoritism and domination but also pragmatism. The DL&W had, historically, always been the much better managed railroad.

The Erie Lackawanna could have certainly used the knowledge and expertise of Lackawanna's top management playing a more direct role in the new company.

Erie Lackawanna F7A's await their next assignment at Deposit, New York in August, 1969. By this date the F units had been relegated to helper service. Author's collection.

Erie Lackawanna F7A's await their next assignment at Deposit, New York in August, 1969. By this date the F units had been relegated to helper service. Author's collection.An Erie man, Harry Von Miller, was given EL's first chairmanship as well as duties as president and chief operating officer. His immediate second in command was the Lackawanna's former chief, Perry Shoemaker.

Miller retired just months after EL's creation but instead of Shoemaker being named his replacement another Erie man got the job, Milton McInnes.

Shoemaker received chairmanship of the board but still carried no direct decision making duties and later said so: "I was made chairman, but I certainly didn't run the railroad."

Beyond managerial issues the hope for savings and higher earnings was immediately dashed; in 1961 the company lost more than $26.4 million and $16.6 million the following year.

The EL proved itself a smaller version of the later Penn Central disaster; incoming officers did not work together and the merger was rushed through without proper time to vet and work out all of the details for a smooth transition.

As the Erie's team dominated the show (similar to the PRR at Penn Central), Lackawanna managers eventually left the company or found work with other railroads. By 1962, the road's long term debt stood at more than $322 million and its future appeared grim.

An interesting lash-up of Erie Lackawanna power is on the former Erie at Binghamton, New York in February, 1966. Author's collection.

An interesting lash-up of Erie Lackawanna power is on the former Erie at Binghamton, New York in February, 1966. Author's collection.Enter William "Bill" White, a highly respected executive who had started his career with the Erie and worked his way up the corporate ladder to eventually head several companies including the Virginian, Lackawanna, and even the mighty New York Central.

He formally joined Erie Lackawanna on June 18, 1963 and immediately set about streamlining operations by:

- Restructuring the road's debt.

- Increasing borrowing power to implement capital improvements (notable here was more more than $59 million in loans to acquire new locomotives and rolling stock).

- Doing away with the road's aggressive but failed less-than-carload (LCL) policies to focus on profitable long-haul movements (such as intermodal/TOFC and general merchandise).

- Trying unsuccessfully to eliminate money-losing commuter operations around New York, and bringing in more effective managers. Ironically, this move resulted in many former Lackawanna officers replacing those of Erie heritage.

Erie Lackawanna SD45-2 #3680 at Croxton Yard in Secaucus, New Jersey, circa 1975. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna SD45-2 #3680 at Croxton Yard in Secaucus, New Jersey, circa 1975. American-Rails.com collection.White also looked for a merger partner, believing this was the only true way EL could survive. The Norfolk & Western eventually agreed to acquire the road but from a distance.

To protect itself from EL's financial condition and heavy debt, The Friendly Service Route was placed within a new holding company known as Dereco, Inc. (an interesting name with an interesting history, it would later include the Delaware & Hudson).

The Interstate Commerce Commission approved the idea during December of 1966. The following spring, Bill White passed away unexpectedly and was later replaced by Jack Fishwick from the Norfolk & Western under the corporate banner of the Erie Lackawanna Railway formed on March 1, 1968.

Fishwick's immediate subordinate was the accomplished Gregory Maxwell who was given the presidency. The loss of White was a big blow to the company; he had greatly turned around its situation and avoided bankruptcy.

Although White was unable to eliminate the suffocating commuter operations (long-distance services ended with the cancellation of the Phoebe Snow on November 27, 1966 and later the Lake Cities on January 6, 1970) he accomplished much during his few years.

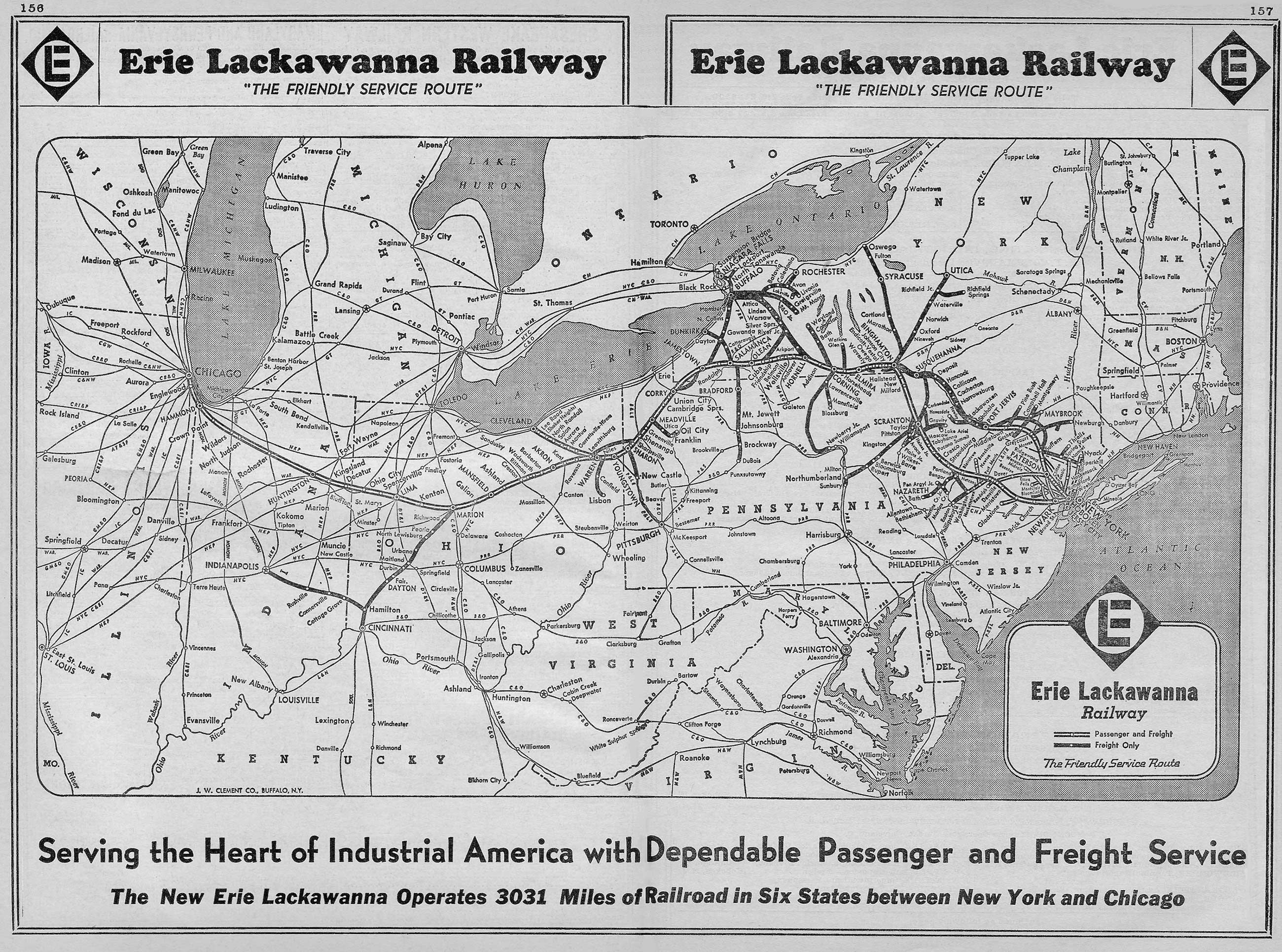

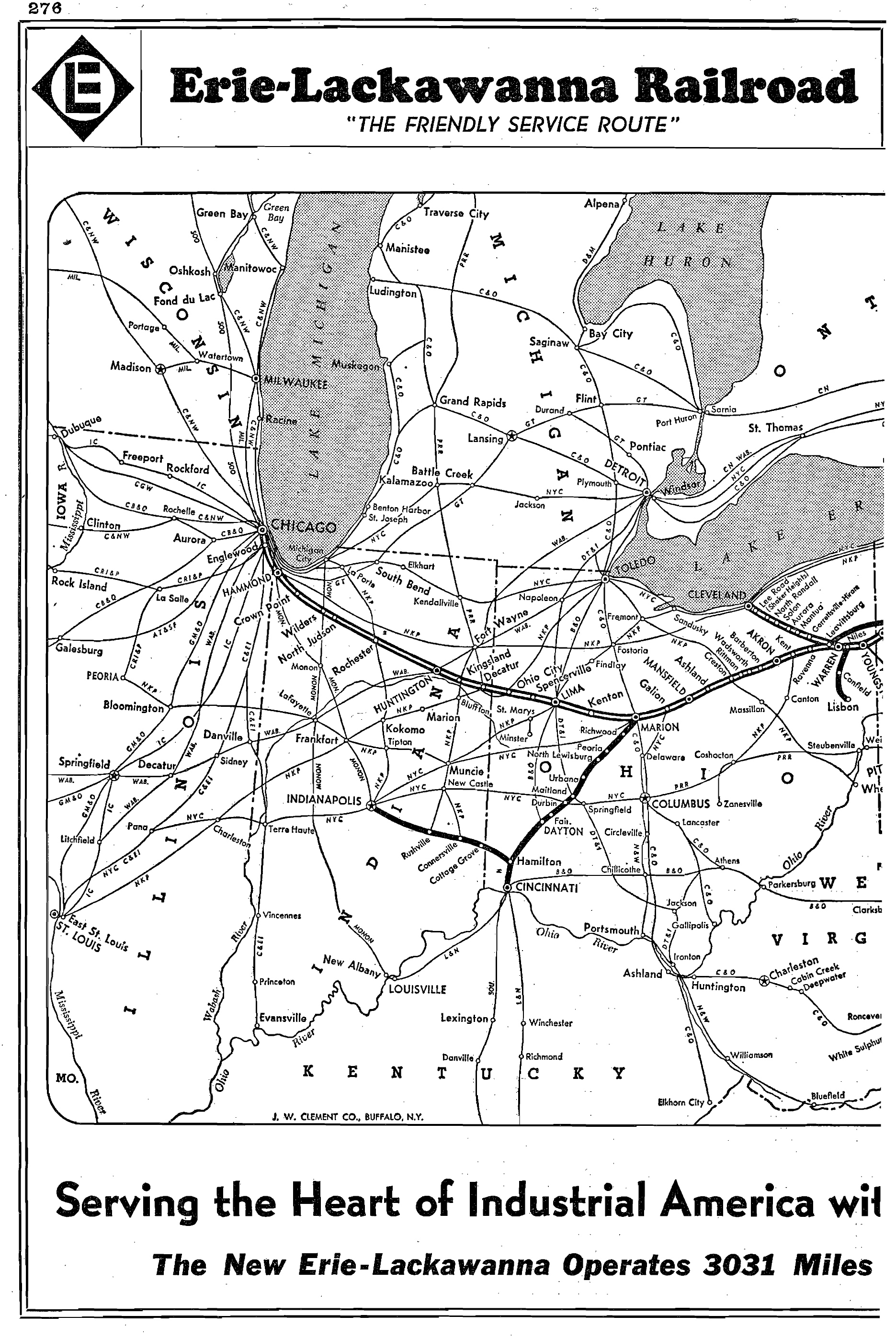

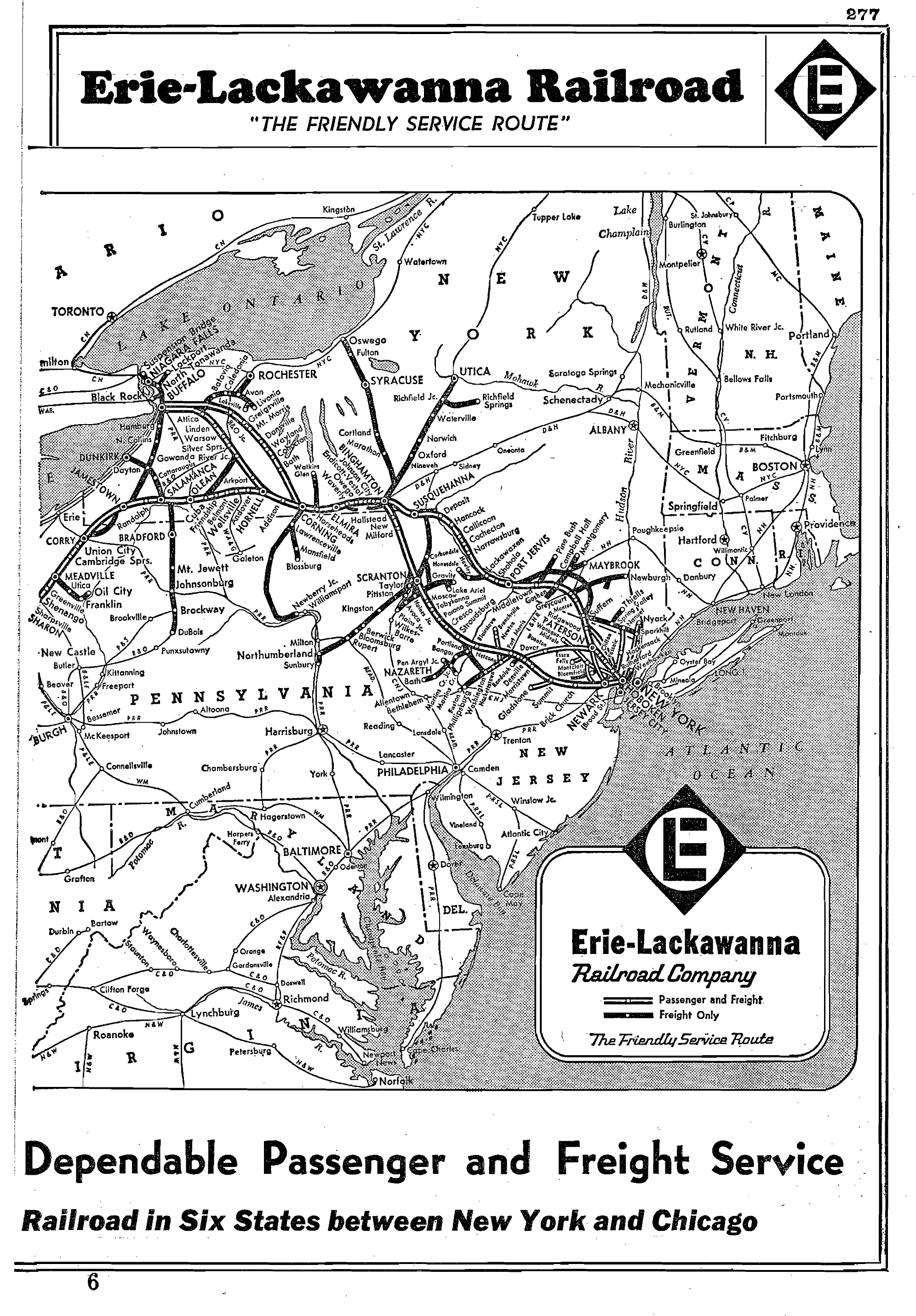

System Map (1969)

By the late 1960s the EL had posted its first ever profits thanks to aggressive cost-cutting, downsizing, and marketing.

The latter step paid off with the railroad gaining new intermodal/piggyback services and a contract with the United Parcel Service (UPS) in 1970 (this gave the EL five new intermodal trains between New York and Chicago), which continued until the road disappeared into Conrail.

For years, executives from John W. Barriger of the 1920s to Fishwick himself, recognized the Erie's one vital asset, its high and wide Chicago main line devoid of clearances, stiff grades, and sharp curves.

A pair of Erie Lackawanna F7A's layover between assignments at Penn Central's terminal in Maybrook, New York during August of 1972. Henry Butz, photo.

A pair of Erie Lackawanna F7A's layover between assignments at Penn Central's terminal in Maybrook, New York during August of 1972. Henry Butz, photo.Penn Central

Alas, the colossal Penn Central merger, created on February 1, 1968 through the Pennsylvania and New York Central, began a quick secession of problems for EL just after it posted net incomes that year and into 1969.

The new conglomerate, which added the New Haven on January 1, 1969, severely hurt The Friendly Service Route's freight tonnage. The New Haven had long been an important interchange partner at Maybrook, New York via the Poughkeepsie Bridge transferring tens of thousands of carloads annually.

Erie Lackawanna C425 #2452, a GP9, and an SD45 have a long freight at Croxton Yard in Secaucus, New Jersey in August, 1968. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna C425 #2452, a GP9, and an SD45 have a long freight at Croxton Yard in Secaucus, New Jersey in August, 1968. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.After the first year (1969), numbers dropped by more than a third and had been cut by half through 1970. Since Penn Central could now carry this freight over its own rails there was no need to short-haul itself by interchanging with the Erie Lackawanna.

The declines resulted in more than $17 million of lost annual revenue for EL. On May 8, 1974 the gateway was closed forever when the bridge burned and PC refused to make repairs.

The year 1970 had also witnessed the stunning bankruptcy of Penn Central sending the Northeast's rail industry into chaos; soon, roads which had not already entered receivership were vying for court protection.

Erie Lackawanna F3A #6561 leads an eastbound freight through the PRR interlocking at Kouts, Indiana in November, 1966. Sadly, no rails remain in this small community today. Rick Burn photo.

Erie Lackawanna F3A #6561 leads an eastbound freight through the PRR interlocking at Kouts, Indiana in November, 1966. Sadly, no rails remain in this small community today. Rick Burn photo.Hurricane Agnes

The EL had been able to avoid a similar fate until Hurricane Agnes ravaged the region during June of 1972 causing more than $11 million in damages and lost revenue. The railroad filed for reorganization on June 26, 1972 completing the service disaster across the Northeast.

Not long after its bankruptcy the N&W sold off all interests in the company (roughly $56 million), which was again independent, albeit a realm of the court.

During 1970 Fishwick returned to the Norfolk & Western and handed over the EL's duties to Maxwell, who turned out to be the company's final president and chief executive. Maxwell guided the road as best he could.

In 1973 Congress and President Richard Nixon passed the Shoup-Adams Act (also known as the Regional Rail Reorganization Act, or 3R Act) which stipulated millions in governmental assistance to create what eventually became the quasi-public Consolidated Rail Corporation, or Conrail, to cleanup the mess in the Northeast.

However, EL had the choice of joining or going it alone, eventually deciding upon the latter in 1974. That spring, the bankruptcy judge gave the go ahead for a reorganization and it appeared the railroad would be Conrail's competition to Chicago.

However, after nearly a year of number crunching EL's trustees realized it had little hope of making it on its own and during January of 1975 asked for inclusion into Conrail.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #817 (ex-DL&W) works suburban service with train #1605 (Hoboken, New Jersey - Spring Valley, New York) as it arrives at Hillsdale, New Jersey in August of 1971. Henry Butz photo.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #817 (ex-DL&W) works suburban service with train #1605 (Hoboken, New Jersey - Spring Valley, New York) as it arrives at Hillsdale, New Jersey in August of 1971. Henry Butz photo.Passenger Trains

Lake Cities: Hoboken - Chicago

As planners worked out the details there was a great desire to have two competing Northeastern systems and not one, gigantic monopoly.

There were various proposals put forth, which included the Erie Lackawanna in competition solely against Conrail or have EL acquired by Norfolk & Western while Chessie System would takeover much of the Reading and Jersey Central to reach the Port of New York.

The latter, according to Rush Loving Jr.'s book, "The Men Who Loved Trains," was referred to as the "Three Systems East" plan.

It was the brainchild of Jim McClellan and assistant Gerald Davies. Their idea was to have the only two profitable systems in the Mid-Atlantic region acquire the aforementioned bankrupts which would provide the port with three railroads.

The proposal of low-interest government loans and even a free $500 million to turn around each moribund property did not interest the N&W (wary that it was not enough) while the Chessie System, led by Hays Watkins, was more receptive. With the N&W backpedaling, Chessie was offered the Erie Lackawanna during July of 1975, which became known as the "Two Systems East" plan.

Erie Lackawanna RS2 #900 (ex-Erie #900) layover at the Normal & 51st Yard in Chicago during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna RS2 #900 (ex-Erie #900) layover at the Normal & 51st Yard in Chicago during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.Later that year, in October, the railroad formally agreed to acquire the entirety of Erie Lackawanna east of Sterling, Ohio for $155 million (west of that point the Baltimore & Ohio's line to Chicago would be utilized with the rest of EL sold or abandoned across western Ohio and Indiana).

The last hurdle to clear was negotiating contracts with EL's labor unions. As Mr. Loving's book points out labor had enjoyed lucrative contracts under their former company and would not agree to what was essentially a pay cut under Chessie System.

Erie Lackawanna RS3s #1042 and #1044 (ex-DL&W #904 and #906) are seen here at Clearing Yard in Chicago during September, 1963. Rick Burn photo.

Erie Lackawanna RS3s #1042 and #1044 (ex-DL&W #904 and #906) are seen here at Clearing Yard in Chicago during September, 1963. Rick Burn photo.Conrail

As a result, talks broke down and a deal was ultimately never reached. Time was running out to find a suitable place for the EL in the soon-to-be carved up Northeast as Congress had mandated Conrail launch operations during the first half of 1976.

Alas, with no takers, this proved the fate of EL which was eventually included in Big Blue upon its start date; April 1, 1976. What many had feared with a Conrail takeover happened as the old Erie Lackawanna lines played only a small role in the new conglomerate.

Conrail had no need for three main lines to Chicago and mothballed the EL west of Marion, Ohio during September of 1977.

The Erie Western Railway was formed soon afterwards to operate the ex-EL from Wren, Ohio into Chicago. However, the western extent of the old Erie had never generated much traffic and relied largely on agricultural movements.

The new short line soon realized this and entered bankruptcy during June of 1979. A new startup took over, named the Chicago & Indiana Railway, but failed so quickly that operations ceased before the end of the year.

Erie Lackawanna RS3 #1051 totes a covered hopper and caboose heading east on the road's westbound main as it crosses the Baltimore & Ohio at Sterling, Ohio on December 27, 1975. Today, this area is quite different; the EL's Chicago main line is completely gone along with the tower. However, the B&O remains busy under CSX. Gary Morris photo.

Erie Lackawanna RS3 #1051 totes a covered hopper and caboose heading east on the road's westbound main as it crosses the Baltimore & Ohio at Sterling, Ohio on December 27, 1975. Today, this area is quite different; the EL's Chicago main line is completely gone along with the tower. However, the B&O remains busy under CSX. Gary Morris photo.Postscript

Perhaps a private report prepared by the affluent Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe during May of 1975 best illustrates Erie Lackawanna's potential.

The Santa Fe had been a longtime interchange partner with EL via Chicago and noted that, "an extensive six-year rehabilitation plan would generate a net, after-tax income of $28 million annually" (in 2021 that figure would be $144 million).

Erie Lackawanna F3A #8454, and other power, lays over at the Normal and 51st Street Yard in Chicago on April 21, 1965. Rick Burn photo.

Erie Lackawanna F3A #8454, and other power, lays over at the Normal and 51st Street Yard in Chicago on April 21, 1965. Rick Burn photo.Diesel Roster

The Erie Lackawanna era saw an interesting mix of first, and second, generation power. The EL's declining financial situation throughout the 1960s saw trains led by interesting lashups of F units and SD45s, for example. In addition, the road even regeared E8s for freight service.

The information presented here offers a complete, all-time diesel roster of the Erie Lackawanna, including all first and second generation power it operated.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #828 is eastbound over the old DL&W main line with a mail/express train at Binghamton, New York as it passes the former Erie Railroad engine house in June, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna E8A #828 is eastbound over the old DL&W main line with a mail/express train at Binghamton, New York as it passes the former Erie Railroad engine house in June, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.Switchers

| Road Number(s) | Heritage | Builder/Model | EL Class | Construction Number | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21-22 | Erie 21-22 | Alco/GE/Ingersoll-Rand Box Cab | - | 66951, 66678 | - |

| 25 | Erie 25 | GE Box Cab | - | 11032 | 4/1931 |

| 26 | Erie 26 | GE 44-Tonner | SG-3 | 28504 | 9/1946 |

| 302-305 | Erie 302-305 | Alco HH660 | SA-6-a | 69136, 69153-69155 | 10/1939 |

| 306 - 308 | Erie 306 - 308 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 74935, 74962-74963 | 9/1946-11/1946 |

| 309-311 | Erie 309-311 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 75119, 75121-75122 | 1/1947 |

| 312-316 | Erie 312-316 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 75353-75357 | 8/1947-9/1947 |

| 317 | Erie 317 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 77478 | 4/1950 |

| 318-320 | Erie 318-320 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 77977-77979 | 4/1950-5/1950 |

| 321 | Erie 321 | Alco S-1 | SA-6 | 77080 | 4/1950 |

| 322-323 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 405-406 | Alco HH600 | SA-6-a | 68639-68640 | 1/1934 |

| 324 - 325 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 409 - 410 | Alco HH600 | SA-6-a | 69257-58 | 4/1940 |

| 349-359 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 427 - 437 | EMD SW1 | SE-6 | 1027-1029,1051-1058 | 3/1940-5/1940 |

| 360 | Erie 360 | EMD SW1 | SE-6 | 6148 | 7/1948 |

| 361-365 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 501-505 | EMD SW8 | SE-8 | 14063-14067 | 8/1951 |

| 366-369 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 506-509 | EMD SW8 | SE-8 | 15727-156730 | 6/1952 |

| 370-371 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 510-511 | EMD SW8 | SE-8 | 17885-17886 | 5/1953 |

| 381-383 | Erie 381-383 | BLW DS-4-4-660 | SB-6 | 73043-73044, 73366 | 11/1947 |

| 384-385 | Erie 384-385 | BLW DS-4-4-660 | SB-6 | 73898-73899 | 2/1947 |

| 386-389 | Erie 386-389 | BLW DS-4-4-750 | SB-7 | 74430-74433 | 2/1949, 8/1949 |

| 401-403 | Erie 401-403 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 951-953 | 1/1948 |

| 404-413 | Erie 404-413 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 5129-5138 | 1/1948 |

| 414-416 | Erie 414-416 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 6145-6147 | 11/1948 |

| 417-421 | Erie 417-421 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 7460-7464 | 10/1949 |

| 422-427 | Erie 422-427 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 8911-8916 | 11/1949 |

| 428 | Erie 428 | EMD SW7 | SE-6 | 11825 | 5/1950 |

| 429-433 | Erie 429-433 | EMD SW7 | SE-6 | 12022-12023, 12026, 12024-12025 | 11/1950 |

| 434 | Erie 434 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 13829 | 3/1951 |

| 435-438 | Erie 435-438 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 15933-15936 | 4/1952 |

| 439-440 | Erie 439-440 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 16176-16174 | 4/1952 |

| 441-445 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 461-465 | EMD NW2 | SE-10 | 3391-3395 | 11/1945 |

| 446 - 448 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 551 - 553 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 14068-14070 | 6/1951 |

| 449-452 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 554-557 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 15731-15734 | 7/1952 |

| 453-455 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 558-560 | EMD SW9 | SE-12 | 17887-17889 | 6/1953 |

| 456-463 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 561-568 | EMD SW1200 | SE-12 | 23762-23769 | 5/1957-6/1957 |

| 500-503 | Erie 500-503 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 74809, 74811-74813 | 10/1946-11/1946 |

| 504-508 | Erie 504-508 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 73891-73895 | 11/1946-12/1946 |

| 509 - 512 | Erie 509-512 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 75242, 75247-75248, 75252 | 6/1947-7/1947 |

| 513-514 | Erie 513-514 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 75362-75363 | 7/1947 |

| 515-519 | Erie 515-519 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 76185-76189 | 10/1948-11/1948 |

| 520-523 | Erie 520-523 | Alco S-2 | MSA-10 | 76776-76779 | 6/1949 |

| 524-525 | Erie 524-525 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 77825-77826 | 11/1949-12/1949 |

| 526-527 | Erie 526-527 | Alco S-4 | MSA-10 | 78716, 79530 | 4/1951, 1/1952 |

| 528-529 | Erie 528-529 | Alco S-4 | SA-10 | 80089-80090 | 10/1952 |

| 530-531 | Erie 530-531 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 75550, 75552 | 12/1947 |

| 532-533 | Erie 532-533 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 75554, 75649 | 12/1947 |

| 534-535 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 475-476 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 73641-73642 | 9/1945 |

| 536-538 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 477-479 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 74324-74326 | 9/1945 |

| 539-540 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 480-481 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 75663-75664 | 3/1948 |

| 541-542 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 482-488 | Alco S-2 | MSA-10 | 76789-76795 | 6/1949-7/1949 |

| 543-547 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 484-488 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 76791-76795 | 6/1949-7/1949 |

| 548-550 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 489-491 | Alco S-2 | SA-10 | 76926-76928 | 6/1949-7/1949 |

| 600-601 | Erie 600-601 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10a | 72808-72809 | 11/1946-12/1946 |

| 602-604 | Erie 602-604 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 73568-73570 | - |

| 605-606 | Erie 605-606 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 73766-73767 | 6/1948 |

| 607-608 | Erie 607-608 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 73959-73960 | 3/1949 |

| 609-610 | Erie 609-610 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 74203-74204 | 6/1949 |

| 611-615 | Erie 611-615 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 74616-74620 | 7/1949-8/1949 |

| 616 | Erie 616 | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | SB-10 | 74196 | 9/1949 |

| 617-618 | Erie 617-618 | BLW S-12 | SB-12 | 74875-74876 | 2/1951 |

| 619-628 | Erie 619-628 | BLW S-12 | SB-12 | 75672-75681 | 4/1952-5/1952 |

| 650-655 | Erie 650-655 | Lima-Hamilton 1000 HP Switcher | MSL-10 | 9328-9333 | 7/1949-8/1949 |

| 656-659 | Erie 656-659 | Lima-Hamilton 1000 HP Switcher | MSL-10 | 9340-9341, 9343-9344 | 10/1949 |

| 660-665 | Erie 660-665 | Lima-Hamilton 1200 HP Switcher | MSL-12 | 9443-9447, 9456 | 7/1950-8/1950 |

| B21, B22, B25 | Erie B21, B22, B25 | Yard Slugs | - | - | - |

A shined up Erie Lackawanna GP7, #1209, was photographed here in Buffalo, New York on August 28, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A shined up Erie Lackawanna GP7, #1209, was photographed here in Buffalo, New York on August 28, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Early Road-Switchers

| Road Number(s) | Heritage | Builder/Model | Construction Number | Date Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900-901 | Erie 900-901 | Alco RS2 | MPSA-15 | 76973-76974 | 6/1949 |

| 902-904 | Erie 902-904 | Alco RS2 | MPSA-15 | 77405-77407 | 9/1949 |

| 905-913 | Erie 905-913 | Alco RS2 | MPSA-15 | 77546-77554 | 11/1949 |

| 914-915 | Erie 914-915 | Alco RS3 | MPSA-16 | 78322-78323 | 10/1950 |

| 916-923 | Erie 916-923 | Alco RS3 | MPSA-16 | 78555-78562 | 4/1951 |

| 924-927 | Erie 924-927 | Alco RS3 | MPSA-16 | 79629-79632 | 2/1952 |

| 928-933 | Erie 928-933 | Alco RS3 | MPSA-16 | 80226-80231 | 10/52-3/1953 |

| 1000-1004 | Erie 1000-1004 | Alco RS2 | MPSA-15 | 77555, 77863-77866 | 11/1949, 12/1949 |

| 1005-1006 | Erie 1005-1006 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16 | 77975-77976 | 4/1950 |

| 1007-1036 | Erie 1007-1028 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16 | 78305-78314, 78320-78321, 78547-78554, 79359-79360 | 9/1950-10/1950 |

| 1029-1036 | Erie 1029-1036 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16D | 80116-80123 | 7/1952 |

| 1037-1038 | Erie 1037-1038 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16D | 80224-80225 | 10/1952 |

| 1039-1042 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 901-904 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16-4 | 78076-78079 | 8/1950 |

| 1043-1048 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 905-910 | Alco RS3 | MFSA-16D-4 | 78573-78578 | 4/1951 |

| 1049-1056 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 911-918 | Alco RS-3 | MFSA-16D-4 | 79667-79674 | 3/1952 |

| 1100-1105 | Erie 1100-1105 | BLW DRS-4-4-1500 | MFSB-15 | 73652, 74289-74293 | 11/1949-12/1949 |

| 1106-1107 | Erie 1106-1107 | BLW AS16 | MFSB-16 | 74903-74904 | 5/1951 |

| 1108-1112 | Erie 1108-1112 | BLW AS16 | MFSB-16 | 74980-74982, 74986-74987 | 7/1951, 11/1951 |

| 1113-1120 | Erie 1113-1120 | BLW AS16 | MFSB-16 | 75516-75519, 75538-75541 | 3/1952, 1/1952 |

| 1140 | Erie 1140 | BLW AS16 | MFSB-16 | 74983 | 7/1951 |

| 1150-1153 | Erie 1150-1153 | BLW DRS-6-6-1500 | MFSB-15A | 74714, 74717-74719 | 6/1950, 9/1950 |

| 1154-1158 | Erie 1154-1158 | BLW DRS-6-6-1500 | MFSB-15A | 74779-74783 | 9/1950 |

| 1159-1161 | Erie 1159-1161 | BLW DRS-6-6-1500 | MFSB-15A | 74930-74932 | 9/1950 |

| 1200-1201 | Erie 1200-1201 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15 | 11823-11824 | 8/1950 |

| 1202-1209 | Erie 1202-1209 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15D | 11834-11841 | 10/1950 |

| 1210-1223 | Erie 1210-1223 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15D | 12004-12017 | 10/1950-12/1950 |

| 1224-1227 | Erie 1224-1227 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15 | 12242-12245 | 3/1951 |

| 1228-1230 | Erie 1228-1230 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15 | 15937-15939 | 2/1952 |

| 1231-1233 | Erie 1231-1233 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15 | 16175-16177 | 4/1952 |

| 1234-1246 | Erie 1234-1246 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15 | 16926-16938 | 9/1952 |

| 1260-1265 | Erie 1260-1265 | EMD GP9 | MFSE-17D | 21821-21826 | 6/1956 |

| 1270-1274 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 951-955 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15D | 14059-14062, 15866 | 8/1951, 10/1951 |

| 1275-1284 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 956-965 | EMD GP7 | MFSE-15D | 15717-157726 | 4/1952-5/1952 |

| 1400-1404 | Erie 1400-1404 | EMD GP7 | MPSE-15 | 12021, 12018-12020 | 12/1950 |

| 1406-1409 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 966-970 | EMD GP7 | MPSE-15-6 | 17980-17894 | 2/1953 |

| 1850-1859 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 850-859 | FM H24-66 | MFFM-24D-4 | 24L734-24L743 | 6/1953 |

| 1860-1861 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 860-861 | FM H24-66 | MFFM-24D-4 | 24L1035-24L1036 | 11/1956 |

| 1930-1935 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 930-935 | FM H24-66 | MFFM-24D-4 | 16L687-16L692 | 12/1952 |

Erie Lackawanna F3s, led by #8044, and an F7A layover at Secaucus, New Jersey on February 4, 1968. Peter Klapper photo, Rick Burn collection.

Erie Lackawanna F3s, led by #8044, and an F7A layover at Secaucus, New Jersey on February 4, 1968. Peter Klapper photo, Rick Burn collection.Contemporary Road-Switchers

| Road Number(s) | Builder/Model | EL Class | Construction Number | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 801 - 803* | EMD SD45 | MFE-36D-6 | 32462, 31694-5 | 6/1966, 1/1966 |

| 2401-2415 | Alco C424 | MFA-24D-6 | 84543-84557 | 5/1963-6/1963 |

| 2451-2462 | Alco C425 | MFA-25D-6 | 3392-01 thru 3392-12 | 10/1964 |

| 2501-2504 | GE U25B | MFG-25D-6 | 35160, 35162-35163, 35161 | 9/1964 |

| 2505 - 2512 | GE U25B | MFG-25D-6 | 35164-35171 | 9/1964-10/1964 |

| 2513-2527 | GE U25B | MFG-25D-6 | 35652-35666 | 7/1965-9/1965 |

| 2551-2554 | EMD GP35 | MFE-25D-6 | 29485, 29494-29496 | 9/1964 |

| 2555-2562 | EMD GP35 | MFE-25D-6 | 29486-29493 | 9/1964 |

| 2563 - 2586 | EMD GP35 | MFE-25D-6 | 30595-30618 | 8/1965-9/1965 |

| 3301-3306* | GE U33C | MFG-33D-6 | 36785-36790 | 9/1964 |

| 3307-3315 | GE U33C | MFG-33D-6 | 37054-37062 | 8/1969 |

| 3316-3328 | GE U36C | MFG-36D-6 | 38586-38598 | 10/1971-11/1971 |

| 3351-3356 | GE U34CH | MPG-34D-6 | 37625-37630 | 11/1970-12/1970 |

| 3357-3373 | GE U34CH | MPG-34D-6 | 37935-37951 | 3-5/1971 |

| 3374-3382 | GE U34CH | MPG-34D-6 | 38749-57 | 12/1972-1/1973 |

| 3601-3620 | EMD SD45 | MFE-36D-6 | 33101-33120 | 6/1967 |

| 3621-3634 | EMD SD45 | MFE-36D-6 | 33936-33949 | 5/1968 |

| 3635-3668 | EMD SDP45 | MFE-36-6A | 34994-3653 | 6/1969 |

| 3669-3681 | EMD SD45-2 | MFE-36-6A | 7381-1 thru 7381-10 | 11/1972 |

* In an odd move, Delaware & Hudson traded SD45s #801-803 (built as demonstrators #4352-4354) for Erie Lackawanna U33Cs 3301-3303. While the SD45s retained their numbers on the EL, the U33Cs were renumbered as D&H 751-753.

The railroads returned the locomotives to one another in December, 1975 and the U33Cs were renumbered back to 3301-3303.

Erie Lackawanna PA-1 #858 (ex-Erie #858) is seen here in Chicago during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna PA-1 #858 (ex-Erie #858) is seen here in Chicago during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.Freight Cab Units

| Road Number(s) | Heritage | Builder/Model | Construction Number | Date Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6011,6014 - 6021,6024 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 601A,601C - 602A,602C | EMD FTA | FE-13DD | 2711-2714 | 4/1945-5/1945 |

| 6012, 6022, 6032, 6042 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 601B-604B | EMD FTB | FE-13DD | 2719-2722 | 4/1945-5/1945 |

| 6031,6034 - 6041,6044 | DLW 603A,603C - 604A,604C | EMD FTA | FE-13DD | 2717, 2716, 2717, 2715 | 5/1945 |

| 6051,6054 - 6061,6064 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 605A,605C - 606A,606C | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 3723-3726 | 12/1946 |

| 6052, 6062 | DLW 605B-606B | EMD F3B | FE-15D | 3727-3728 | 12/1946 |

| 6111, 6112, 6114 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 611A, 611B, 611C | EMD F7 | FE-15AD | 4969, 4972, 4970 | 7/1949 |

| 6211, 6212, 6214 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 621A, 621B, 621C | EMD F3 | FE-15D | 4595-4597 | 1/1948 |

| 6311, 6314 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 631A, 631C | EMD F7A | FE-15AD | 4967-4968 | 1/1948 |

| 6321, 6331, 6341, 6351 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 632A-635A | EMD F7A | FE-15AD | 7445-7448 | 7/1949 |

| 6322, 6332, 6342, 6352 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 632B-635B | EMD F7B | FE-15AD | 7449-7452 | 7/1949 |

| 6361 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 636A | EMD F7A | FE-15AD | 7444 | 7/1949 |

| 6362 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 636B | EMD F7A | FE-15AD | 4971 | 7/1949 |

| 6511, 6521, 6531, 6541 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 651A-654A | EMD FTA | FE-13D | 2703-2706 | 5/1945 |

| 6512, 6522, 6532, 6542 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 651B-654B | EMD FTB | FE-13D | 2707-2710 | 5/1945 |

| 6551, 6552, 6561, 6562 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 655A, 655B, 656A, 656B | EMD F3 | FE-15D | 3729-3732 | 1/1947 |

| 6571, 6581, 6591 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 657A-659A | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 4973-4975 | 3/1948 |

| 6601, 6611, 6621 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 660A-662A | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 4976-4978 | 3/1948 |

| 6602, 6612, 6622 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 660B-662B | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 4982-4984 | 3/1948 |

| 7001,7004 : 7051,7054 | Erie 700A,700D : 705A,705D | EMD FTA | FE-13D | 2533-2544 | 10/1944-11/1944 |

| 7002,7003 : 7052,7053 | Erie 700B,700C : 705B,705C | EMD FTB | FE-13D | 2545-2556 | 10/1944-11/1944 |

| 7061, 7064 : 7081, 7084 | Erie 706A, 706D : 708A, 708D | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 4377-4382 | 11/1947 |

| 7062, 7063 : 7082, 7083 | Erie 706B, 706C : 708B, 708C | EMD F3B | FE-15D | 4383-4388 | 11/1947 |

| 7091, 7094 : 7101, 7104 | Erie 709A, 709D : 710A, 710D | EMD F3A | FE-15AD | 7465-7468 | 2/1949 |

| 7092, 7093 : 7102, 7103 | Erie 709B, 709C : 710B, 710C | EMD F3A | FE-15AD | 7469-7472 | 2/1949 |

| 7111, 7114, 7112, 7113 | Erie 711A, 711B, 711C, 711D | EMD F7 | FE-15AD | 10112-10115 | 1/1950 |

| 7121, 7122, 7123, 7124 | Erie 712A, 712B, 712C, 712D | EMD F7 | FE-15AD | 15135-15138 | 12/1951 |

| 7131, 7132, 7134 | Erie 713A, 713B, 713D | EMD F7 | FE-15AD | 13209-13211 (built as Erie 807A, 807B, 807D) | 3/1951 |

| 7133 | Erie 713C | EMD F7B | FE-15AD | 15932 | 3/1952 |

| 7141, 7142, 7143, 7144 | Erie 714A, 714B, 714C, 714D | EMD F3A | FE-15D | 3142-3145 (built as New York, Ontario & Western 821/822/821B/822B) | 3/1948 |

| 7251,7254 : 7271,7274 | Erie 725A,725D : 727A,727D | Alco FA-1 | FA-15D | 75428-75433 | 12/1947 |

| 7252,7253 : 7282,7283 | Erie 725B,725C : 728B,728C | Alco FB-1 | FA-15D | 75597-75603 | 12/1947-1/1948 |

| 7281,7284 : 7321,7324 | 728A,728D : 732A,732D | Alco FA-1 | FA-15D | 75575-75584 | 12/1947 |

| 7292,7293 : 7332,7333 | Erie 729B,729C : 733B,733C | Alco FB-1 | FA-15D | 75745-75574 | 1/1948-2/1948 |

| 7331, 7334 | Erie 733A, 733D | Alco FA-1 | FA-15D | 75705-75706 | 2/1948 |

| 7341, 7344 : 7351, 7354 | Erie 734A, 734D : 735A, 735D | Alco FA-1 | FA-15D | 76713-76716 | 1/1949 |

| 7342, 7343 : 7352, 7353 | Erie 734B, 734C : 735B, 735C | Alco FB-1 | FA-15D | 76713-76716 | 1/1949 |

| 7361, 7364 : 7371, 7374 | Erie 736A, 736D : 737A, 737D | Alco FA-2 | FA-16D | 78184-78187 | 10/1950 |

| 7362, 7363 : 7372, 7373 | Erie 736B, 736C : 737B, 737C | Alco FA-2 | FA-16D | 78194-78197 | 10/1950 |

| 7381, 7384 : 7391, 7394 | Erie 738A, 786D : 739A, 739D | Alco FA-2 | FA-16D | 78620-78623 | 10/1950 |

| 7382, 7383 : 7392, 7393 | Erie 738B, 738C : 739B, 739C | Alco FA-2 | FA-16D | 78503-78505, 78656 | 3/1951-4/1951 |

| 8001, 8004 : 8061, 8064 | Erie 800A, 800D : 806A, 806D | EMD F3A | FE-15 | 4086-4099 | 7/1947 |

| 8002-8062 | Erie 800B-806B | EMD F3B | FE-15 | 4100-4106 | 7/1947 |

| 8411, 8414 : 8421, 8424 | DLW 801A, 801C : 802A, 802C | EMD F3A | FE-15 | 3717-3720 | 12/1947 |

| 8412, 8422 | DLW 801B-802B | EMD F3A | FE-15 | 3721-3722 | 12/1946 |

| 8431, 8414 : 8451, 8454 | DLW 803A, 803C : 805A, 805C | EMD F3A | FE-15 | 4395-4400 | 12/1947 |

| 8432, 8442, 8452 | DLW 803B-805B | EMD F3A | FE-15 | 4401-4403 | 12/1947 |

Passenger Cab Units

| Road Number(s) | Heritage | Builder/Model | Construction Number | Date Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 809 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 820 | EMD E8A | PE-22 | 14019 | 5/1951 |

| 810-811 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 810 - 811 | EMD E8A | PE-22 | 13676-13677 | 1/1951 |

| 812-819 | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 812 - 819 | EMD E8A | PE-22 | 14011-14018 | 4/1951-5/1951 |

| 820-833 | Erie 820-833 | EMD E8A | PE-22 | 12218-12231 | 1/1951-3/1951 |

| 850-854 | Erie 850-854 | Alco PA-1 | PA-20 | 76908-76912 | 4/1949 |

| 855-857 | Erie 855-857 | Alco PA-1 | PA-20 | 77103-77105 | 9/1949 |

| 858-859 | Erie 858-859 | Alco PA-1 | PA-20 | 77501-77502 | 9/1949 |

| 860-861 | Erie 860-861 | Alco PA-1 | PA-20 | 75793-75794 | 11/1949 |

| 862-863 | Erie 862-863 | Alco PA-2 | PA-22 | 78732-78733 | 4/1951 |

This was the Erie Lackawanna, a high and wide pike ideal for intermodal service. It still witnessed nearly 25 trains per day before Conrail but after its start fell largely silent, as seen here near Sterling, Ohio in December, 1976. Gary Morris photo.

This was the Erie Lackawanna, a high and wide pike ideal for intermodal service. It still witnessed nearly 25 trains per day before Conrail but after its start fell largely silent, as seen here near Sterling, Ohio in December, 1976. Gary Morris photo.Santa Fe's report went on to state that, "The E-L is the only Eastern railroad which has the right-of-way suitable for high-speed, long-haul service without superfluous, congested and expensive urban terminals every hundred miles."

"The absence of clearance restrictions, an extensive double track main line, and interdivisional crew districts are indicative of the physical resources which are presently being utilized at a level far below capacity."

In another words, the EL offered great potential and would certainly have blossomed during the intermodal revolution of the 1980s.

Alas, the political environment of the time (which saw railroads as an archaic mode of transportation) and strict regulation, coupled with EL's heavy debt, resulted in a near impossible situation for the carrier.

The government certainly had the ability and means to save the road by creating a second Conrail but believing the Northeast already held far too much excess trackage (a notion quite true in many respects) was not willing to do so.

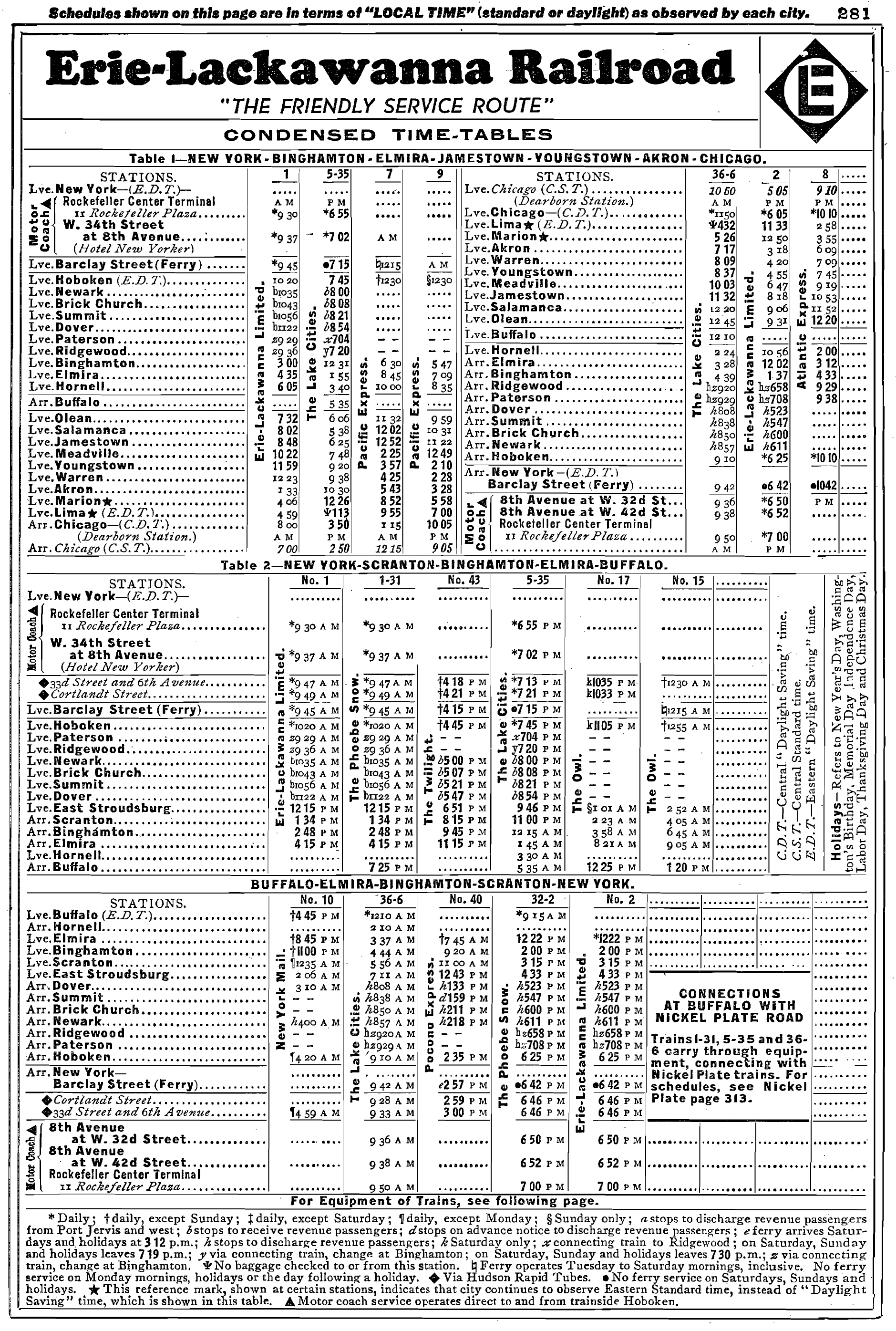

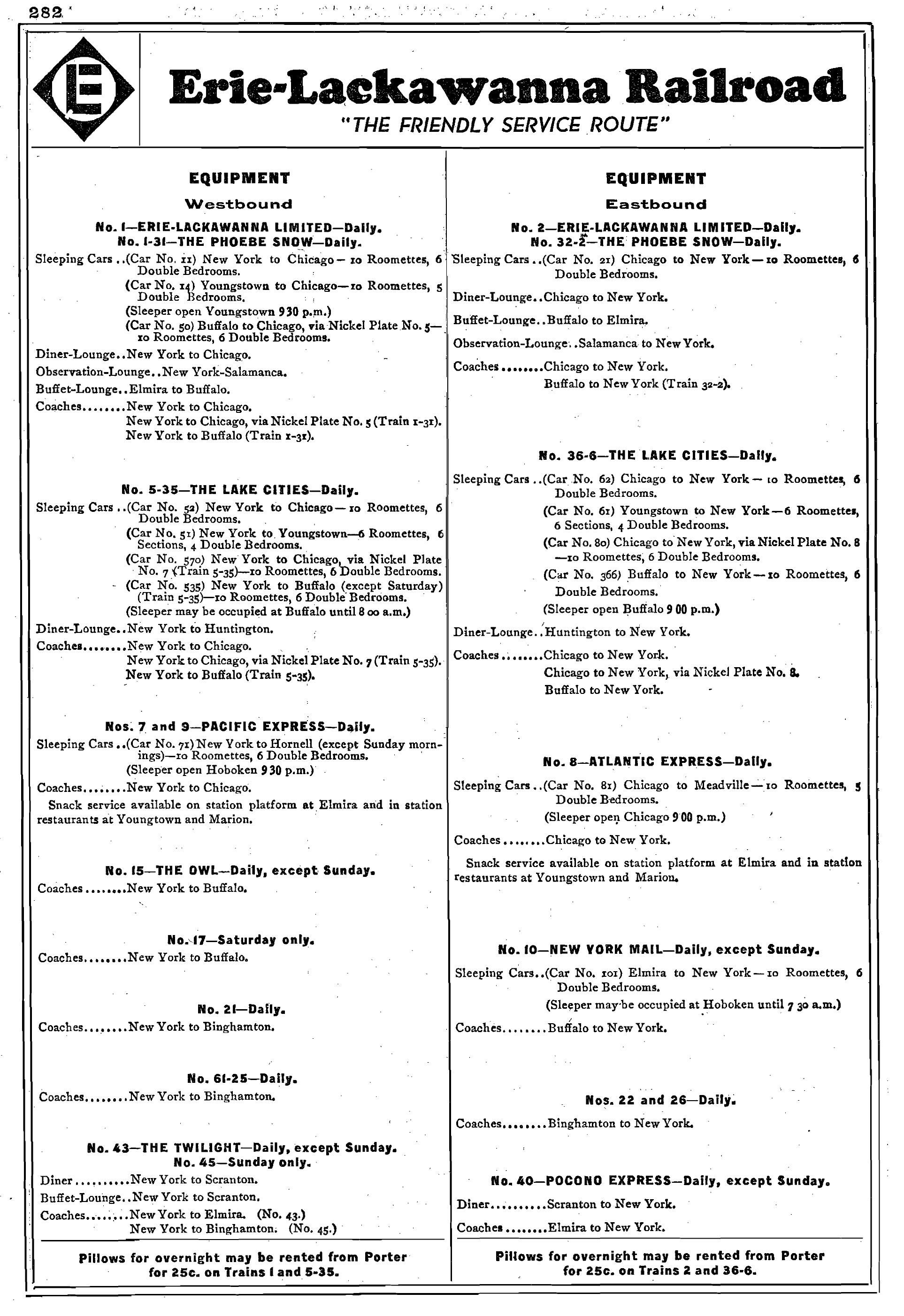

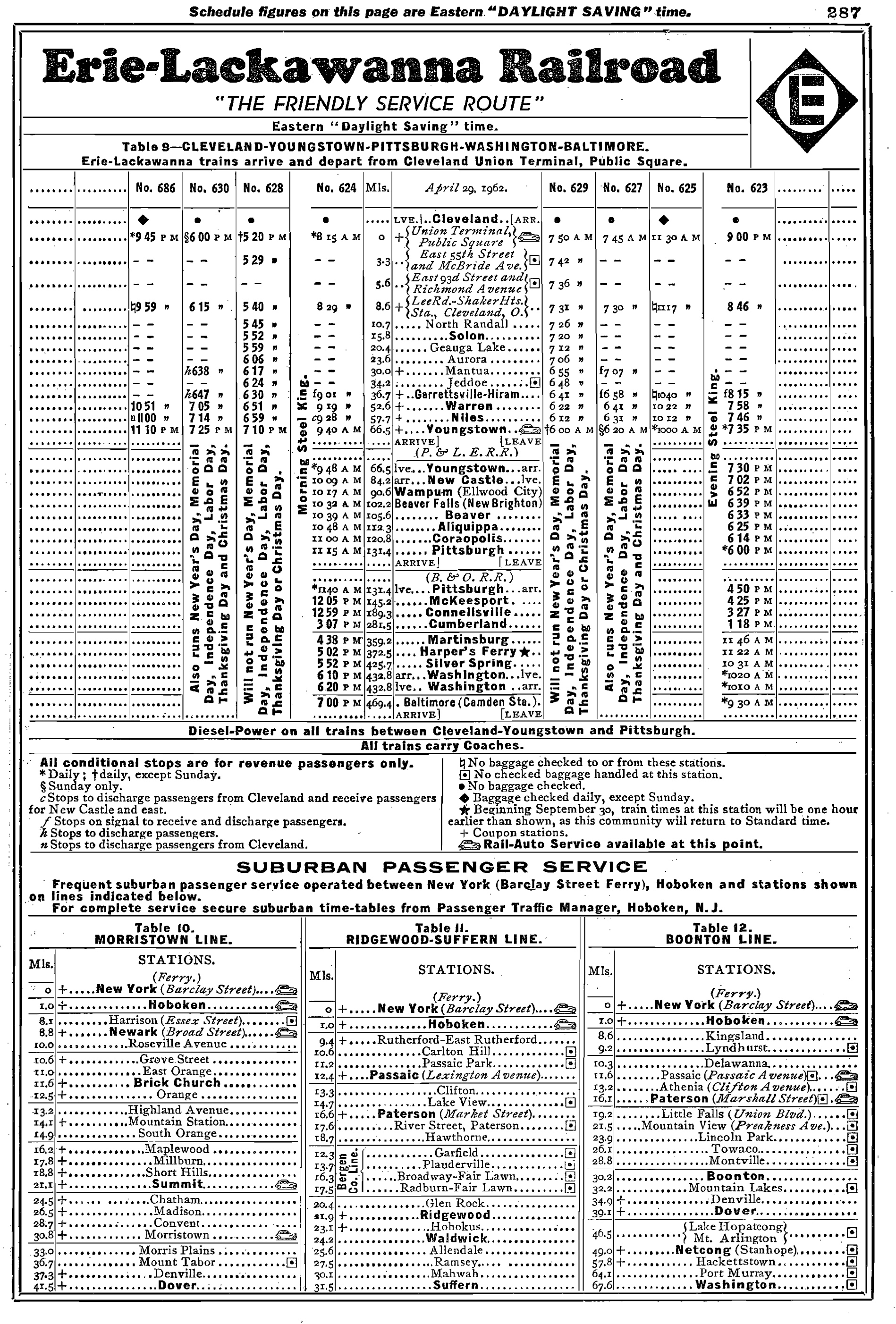

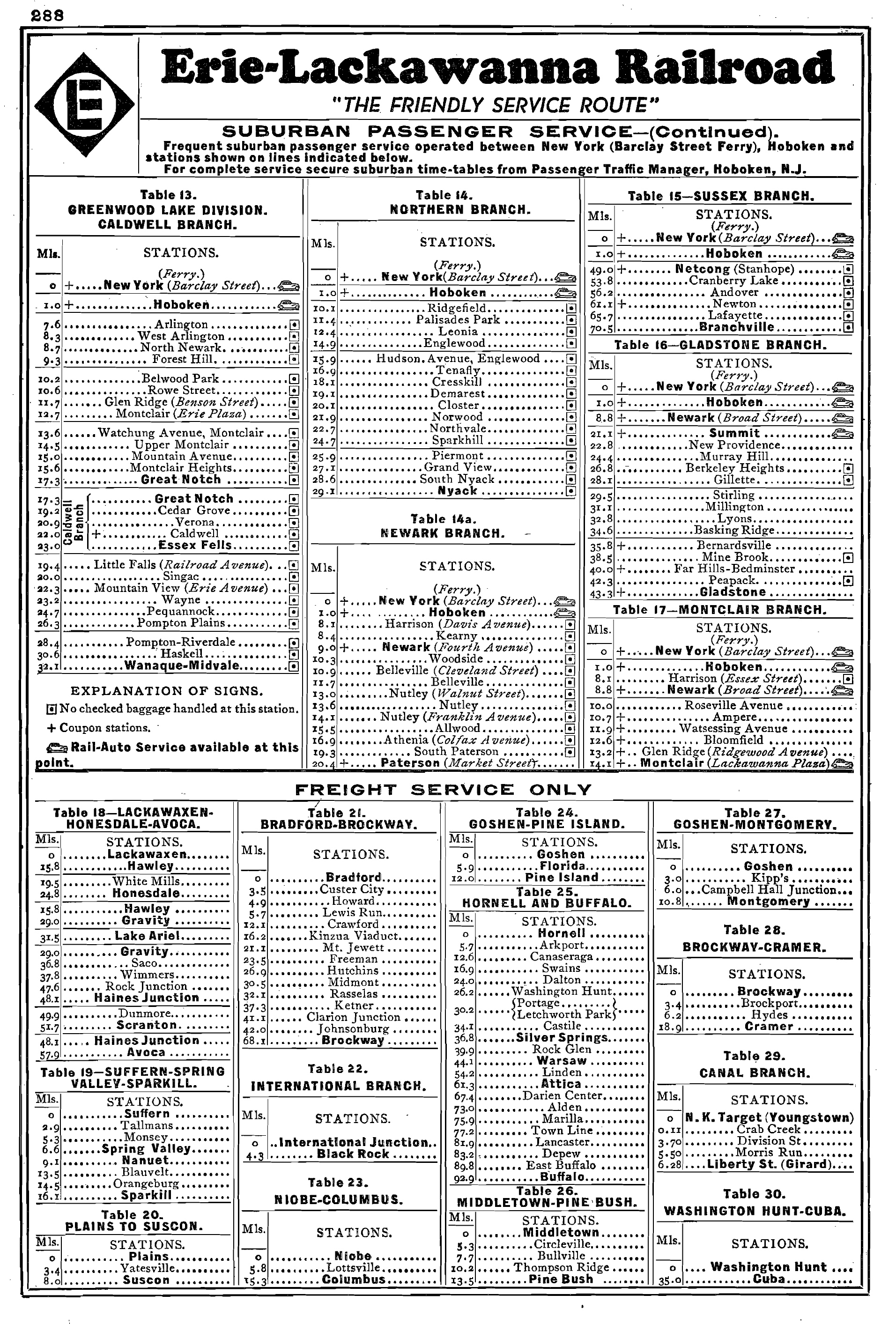

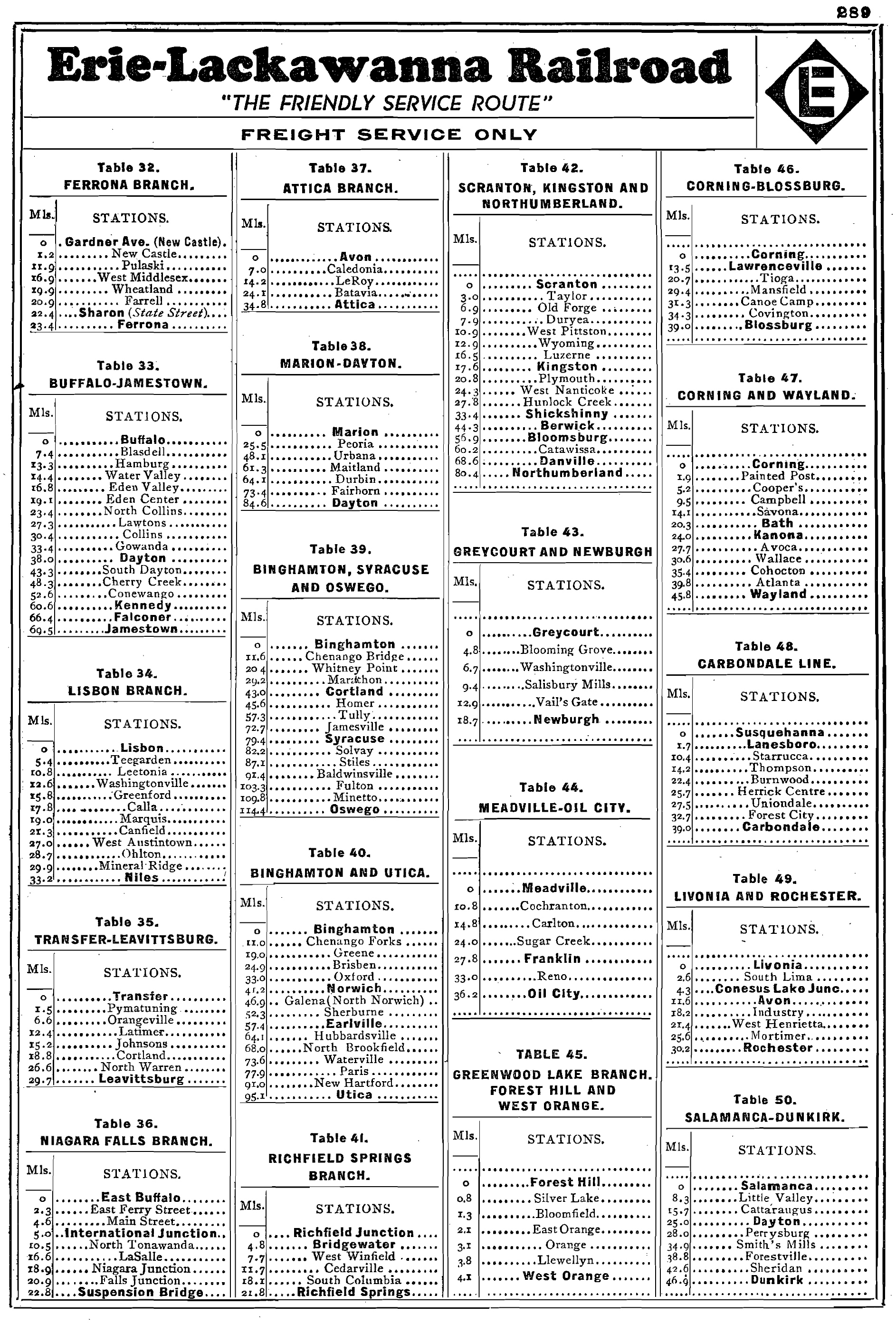

Timetables (May, 1962)

Photo Gallery

A pair of Erie Lackawanna U25Bs, led by #2509, are westbound near Akron, Ohio on a gloomy February 28, 1965. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Erie Lackawanna U25Bs, led by #2509, are westbound near Akron, Ohio on a gloomy February 28, 1965. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Erie Lackawanna SD45 #3622 was photographed here at Sloan, New York on February 18, 1974. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Lackawanna SD45 #3622 was photographed here at Sloan, New York on February 18, 1974. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Recent Articles

-

Virginia Railway Express Surpasses 100 Million Riders

Mar 02, 26 07:57 PM

In October 2025, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) reached one of the most significant milestones in its history, officially carrying its 100 millionth passenger since beginning operations more than… -

Restoration Continues On New Haven RS3 529

Mar 02, 26 11:29 AM

The Railroad Museum of New England's efforts to completely restore New Haven RS3 529 to operating condition as they provide the latest updates on the project. -

American Freedom Train No. 250 Completes FRA Steam Test

Mar 02, 26 10:17 AM

One of the most anticipated steam locomotive restorations in modern preservation reached a major milestone this week as American Freedom Train 4-8-4 No. 250 successfully completed a federally observed… -

Indiana's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 10:00 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Maryland's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:54 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

California's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:46 AM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:42 AM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

New York Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:32 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:30 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

NS Completes 1,000th DC-to-AC Locomotive Conversion

Mar 01, 26 11:26 PM

In October 2025, Norfolk Southern Railway reached one of the most significant mechanical milestones in modern North American railroading, announcing completion of its 1,000th DC-to-AC locomotive conve… -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:11 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

North Carolina Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:09 AM

The springs are typically warm and balmy in the Tarheel State and a few tourist trains here offer Easter-themed train rides. -

Maryland Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:05 AM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:03 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Indiana Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:01 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 09:58 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Metro-North Unveils Veterans Heritage Locomotive

Feb 28, 26 11:02 PM

The Metro-North Railroad marked Veterans Day 2025 with the unveiling of a striking new heritage locomotive honoring the service and sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Pennsylvania's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:46 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Alabama's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:44 AM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Georgia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:43 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:40 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Mexico Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:37 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:35 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

KC Streetcar Ridership Surges With Opening of Main Street Extension

Feb 27, 26 11:24 AM

Kansas City’s investment in modern urban rail transit is already paying dividends, especially following the opening of the Main Street Extension. -

“Auburn Road Special” Excursions To Aid URHS

Feb 27, 26 09:04 AM

The United Railroad Historical Society of New Jersey (URHS) and the Finger Lakes Railway have jointly announced a special series of rare-mileage passenger excursions scheduled for April 18–19, 2026. -

New Jersey Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:53 AM

New Jersey is home to several museums and a few heritage railroads that vividly illustrate its long history with the iron horse. A few host special events for the Easter holiday. -

Washington Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:49 AM

You can find many heritage railroads in Washington State which illustrates its rich history with the iron horse. A few host Easter-themed events each spring. -

South Dakota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:46 AM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:42 AM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Pennsylvania Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:38 AM

Wine tasting trains are a unique and enchanting way to explore the state’s burgeoning wine scene while enjoying a leisurely ride through picturesque landscapes. -

West Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:37 AM

West Virginia, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes and rich history, offers visitors a unique way to explore its rolling hills and picturesque vineyards: wine tasting trains. -

Nebraska Lawmakers Advance UP Tax Incentive Bill

Feb 27, 26 08:31 AM

Nebraska lawmakers are advancing new economic development legislation designed in large part to ensure that Union Pacific Railroad maintains its historic corporate headquarters in Omaha. -

UP And NS Ask FRA To Waive Cab-Signals For Big Boy 4014

Feb 26, 26 01:44 PM

Union Pacific’s famed 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 could see new eastern mileage on Norfolk Southern in 2026—but first, the two railroads are asking federal regulators for help bridging a technology gap… -

Cando Rail & Terminals to Acquire Savage Rail

Feb 26, 26 11:29 AM

Cando Rail & Terminals has signed a definitive agreement to acquire Savage Rail, the U.S. rail-services business of Savage Enterprises LLC. -

Dollywood To Convert Steam Locomotives From Coal To Oil

Feb 26, 26 09:20 AM

Dollywood’s most recognizable moving landmark—the Dollywood Express—will soon look and feel a little different. -

Missouri Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:10 AM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:08 AM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Utah Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:04 AM

Utah, a state widely celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty and dramatic landscapes, is also gaining recognition for an unexpected yet delightful experience: wine tasting trains. -

Vermont Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:02 AM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Amtrak San Joaquins Becomes Gold Runner

Feb 26, 26 08:59 AM

California’s busy state-supported rail link between the Bay Area and the Central Valley entered a new chapter in early November 2025, when the familiar Amtrak San Joaquins name was officially retired. -

Canadian National Marks 30 Years Since Privatization

Feb 25, 26 02:07 PM

Canadian National Railway marked a milestone last fall that helped redefine not only the company, but the modern Canadian freight-rail landscape: 30 years since CN went private. -

Western Rail Coalition: Returning Passenger Trains To Colorado

Feb 25, 26 11:48 AM

Colorado’s passenger-rail conversation is often framed as two separate stories: a Front Range “spine” along I-25, and a harder, longer-term quest to offer real alternatives to the I-70 mountain drive. -

Union Pacific Unveils Full Schedule For Big Boy 4014

Feb 25, 26 09:24 AM

Union Pacific Railroad has released the complete western leg schedule for its groundbreaking 2026 Big Boy No. 4014 Coast-to-Coast Tour. -

Kentucky Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:55 AM

In the realm of unique travel experiences, Kentucky offers an enchanting twist that entices both locals and tourists alike: murder mystery dinner train rides. -

Utah Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:53 AM

This article highlights the murder mystery dinner trains currently avaliable in the state of Utah! -

Rhode Island Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:50 AM

It may the smallest state but Rhode Island is home to a unique and upscale train excursion offering wide aboard their trips, the Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad. -

Oregon Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:45 AM

For those looking to explore this wine paradise in style and comfort, Oregon's wine tasting trains offer a unique and enjoyable way to experience the region's offerings. -

Amtrak Posts Record Ridership and Revenue in Fiscal Year 2025

Feb 24, 26 11:22 PM

Amtrak, the national passenger rail operator, has announced historic results for Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25), reporting the highest ridership and revenue in its history as demand for train travel across t… -

NC By Train Posts Busiest Month In 35-year History

Feb 24, 26 06:17 PM

North Carolina’s state-supported passenger rail service, marketed under the NC By Train brand, reached a milestone last fall. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years.