Minneapolis and St Louis Railway: Map, Timetables, History

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

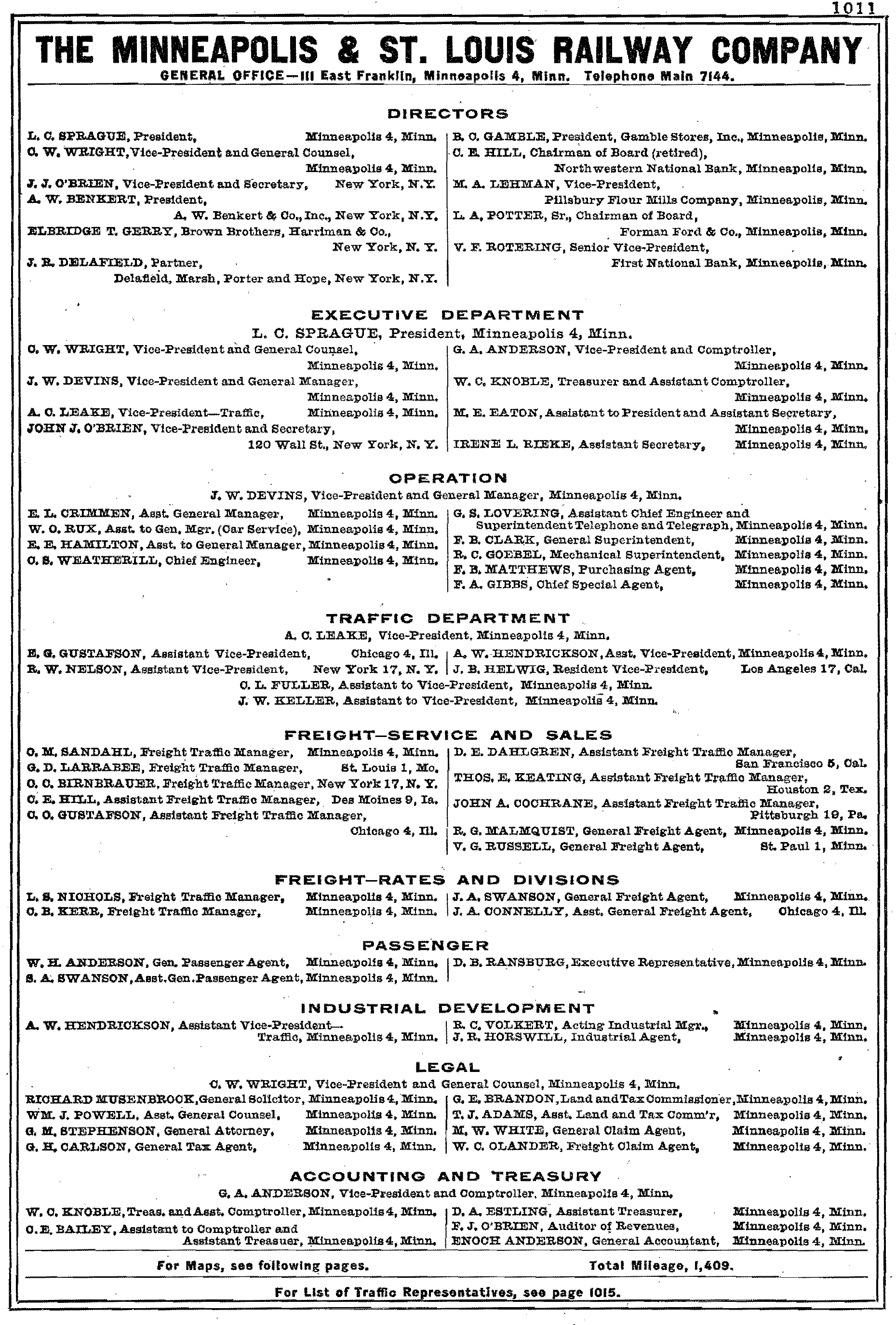

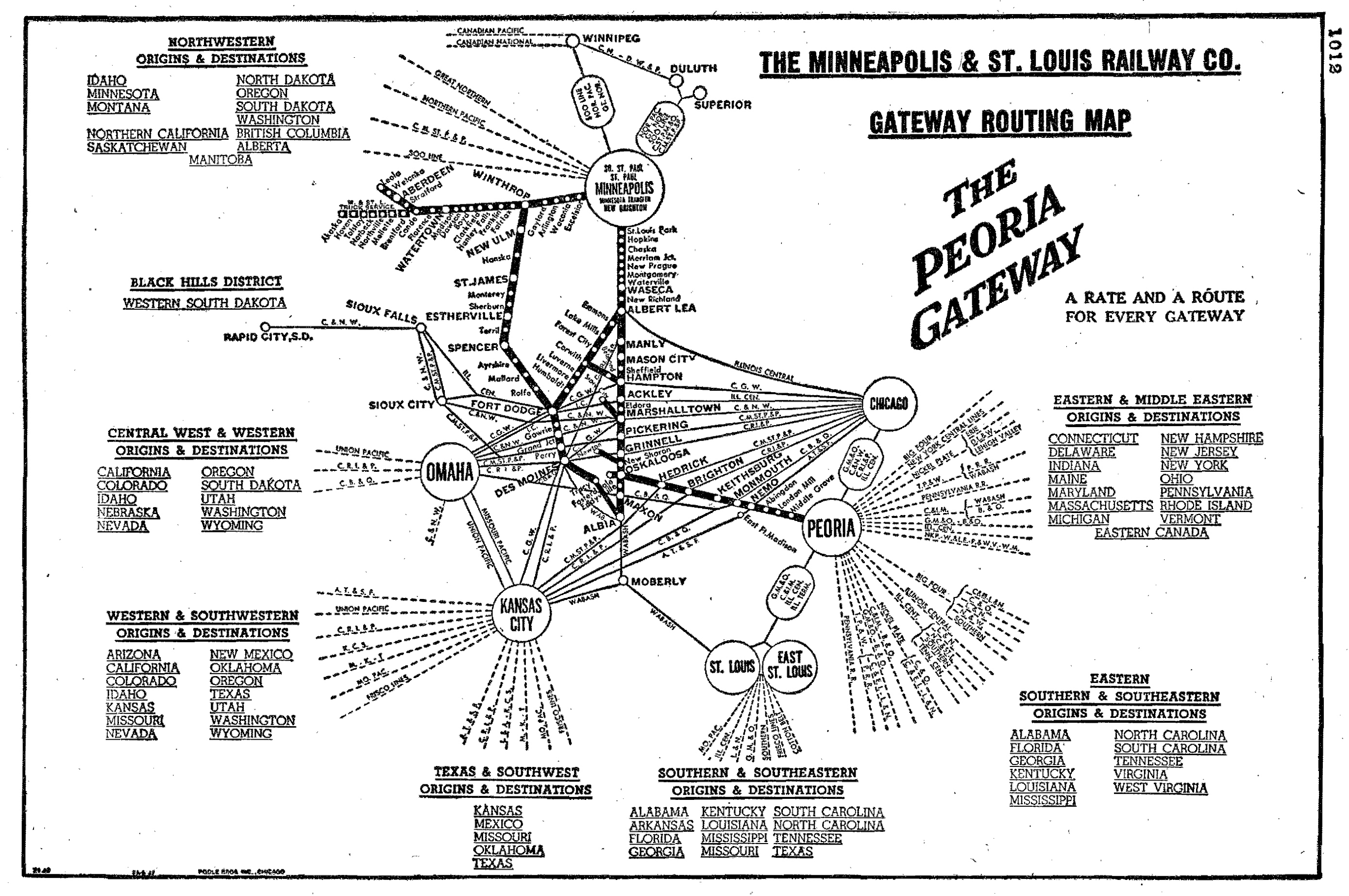

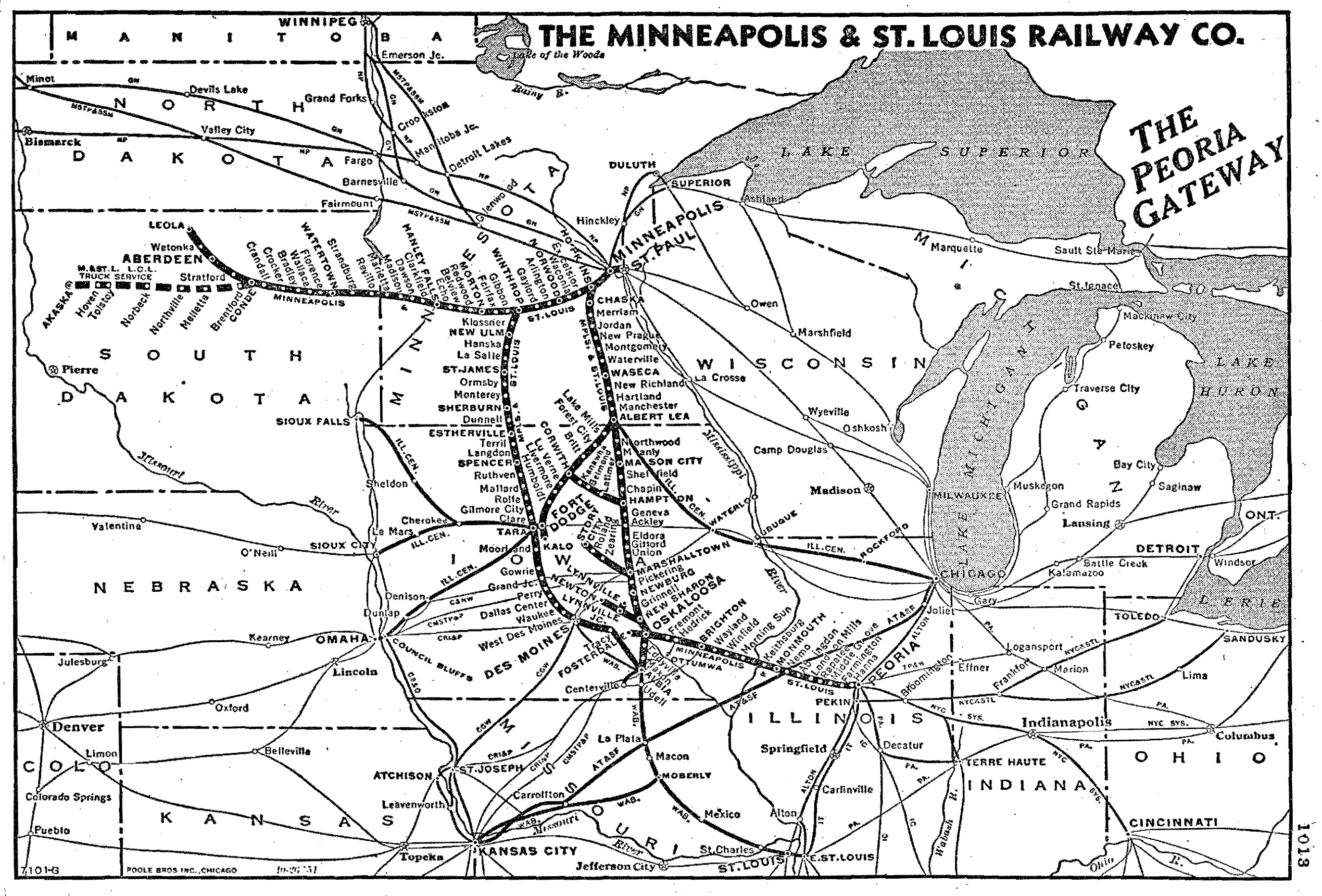

The Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway may have been the smallest classic granger but The Peoria Gateway perhaps best typified Midwestern railroading. Here was a system of only a few hundred miles that relied heavily on agricultural and local traffic throughout its corporate existence.

Despite eroding business in the postwar years, a sea of larger competitors, and a stagnate customer base, the M&StL somehow remained profitable right up until its acquisition by Chicago & North Western in 1960.

The Tootin' Louie's history began in earnest shortly after the Civil War to serve flour mills in a young Twin Cities. The railroad eventually expanded to the south and west although never reached markets larger than Minneapolis/St. Paul.

There were great struggles early on and its leadership, ever weary of upsetting the status quo, shied away from accessing larger cities like Chicago, Omaha, and Kansas City for fear of retribution by the bigger carriers.

During the 1930's new leadership arrived in the form of Lucian Sprague who helped guide the company through a period of prosperity before ownership sold out to C&NW.

Always quick to rip up its new acquisitions, the North Western spent the next two decades systematically abandoning most of M&StL's network. Today, only a few disconnected segments remain in use.

Photos

A pair of Minneapolis & St. Louis F7As, led by #408, have a short train at Albia, Iowa on May 26, 1961. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Minneapolis & St. Louis F7As, led by #408, have a short train at Albia, Iowa on May 26, 1961. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.History

The Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway owes its existence not only to Minneapolis and St. Paul but also the stunningly beautiful Falls of St. Anthony. These falls no longer flow in their natural state due to civil engineering projects carried out by the United States Army Corps of Engineers during the mid-20th century.

However, during the early 1800's the only notable natural falls on the Upper Mississippi River was not impeded by human intervention. The first U.S. presence here, Fort Snelling, opened in 1825.

It was a major Army outpost to protect growing American interests and frontiersmen. This gave way to commercial development through utilization of the falls' awesome power.

A sawmill owned by Franklin Steele began production in September of 1848 to tap the area's rich timber tracts, followed by flour milling which had been ongoing since the fort's early years.

The latter eventually surpassed lumber production although both came to define the local economy. In 1849 the town of St. Anthony was incorporated on the east side of the river while directly to the west Minneapolis was formed in 1867.

The area quickly grew to serve these industries, which meant the iron horse would be needed. While early predecessors of the Chicago & North Western, Milwaukee Road, and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy had already been established at this time all were located to the east, serving Chicago and Milwaukee.

Overview

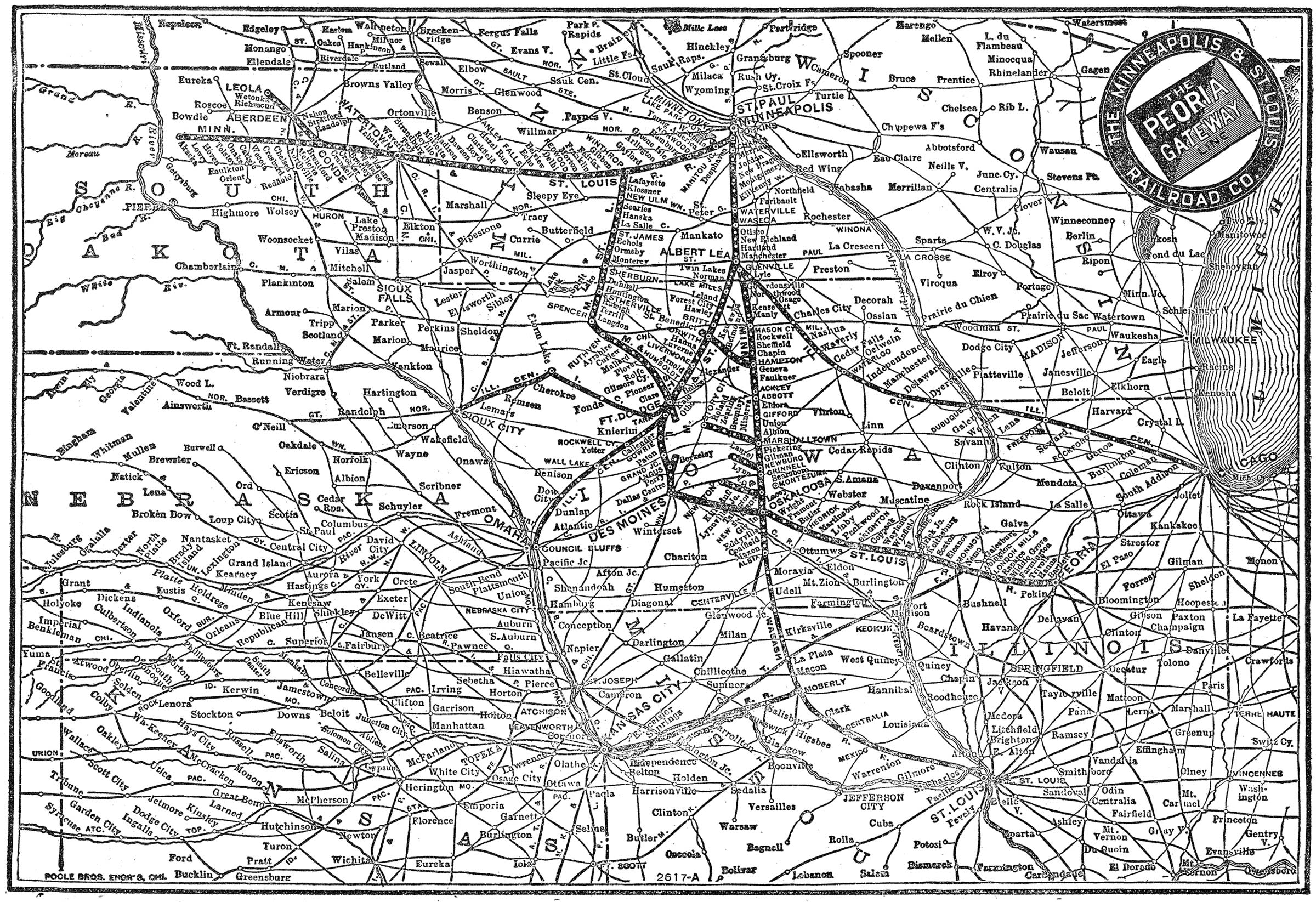

Twin Cities - Conde, South Dakota Conde - Leola/Akaska, South Dakota Twin Cities - Albert Lea - Oskaloosa, Iowa - Albia, Iowa Winthrop, Minnesota - Spencer, Iowa - Fort Dodge, Iowa Albert Lea, Minnesota - Fort Dodge, Iowa - Des Moines, Iowa Des Moines - Oskaloosa Oskaloosa - Peoria, Illinois Corwith - Hampton, Iowa |

|

Because of this business leaders in Minneapolis/St. Anthony (the two merged in 1872) realized it would be up to them to see rail service established to their cities.

In his excellent title, "The Tootin' Louie: A History Of The Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway," author Don Hofsommer notes the first effort in accomplishing this task was the Minnesota Western Rail Road formed in 1853 to build, "from some convenient point to be selected on the Lake St. Croix, or St. Croix River" to St. Paul/St. Anthony.

Unfortunately, the project stalled due to lack of funding. In the meantime the St. Paul & Pacific (future predecessor of James Hill's Great Northern Railway) managed to link St. Paul with St. Anthony in 1862 but still provided no eastern outlet to the national rail network.

On May 26, 1870 the Minnesota state legislator authorized construction of the Minneapolis & St. Louis Railroad (M&StL) for the purpose of, again, serving local flour and sawmills.

This time such a railroad proved more successful as several prominent businessmen pledged financial support including Henry Welles, William Washburn, John Pillsbury (co-founder of C. A. Pillsbury & Company in 1872, which remains a leading producer of baking products), R.J. Baldwin, R.P Russell, W.W. McNair, Isaac Atwater, and Levi Butler.

Logo

By this point, however, railroads were building across the Midwest and converging upon the growing Twin Cities from several directions.

According to Jim Scribbins' book, "The Milwaukee Road Remembered," predecessors of the Milwaukee Road had opened through service from Minneapolis/St. Paul to Milwaukee/Chicago by 1867 while the Lake Superior & Mississippi (LS&M) connected St. Paul with Duluth (156 miles) during 1870.

A pair of recently delivered Minneapolis & St. Louis GP9's, #709 and #702, layover in Minneapolis during October of 1958. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of recently delivered Minneapolis & St. Louis GP9's, #709 and #702, layover in Minneapolis during October of 1958. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

With so much ongoing development M&StL's promoters realized there was no time to waste! Its target for an eastern outlet was the LS&M, which offered a Lake Superior port connection at Duluth. The initial task, ironically, was to construct a subsidiary for the opening of an LS&M interchange.

What was known as the Minneapolis & Duluth Railroad (M&D) was incorporated on May 16, 1871 to build from Minneapolis to White Bear Lake utilizing the StP&P's bridge over the river. The line opened for regular service on August 7th that same year.

While this was ongoing a southern outlet (Minneapolis & St. Louis) was also underway to establish an interchange with the St. Paul & Sioux City (a Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railway predecessor, which later joined the Chicago & North Western).

It opened only a few months after the M&D (November, 1871) at a point one mile south of Carver. Unfortunately, before further construction towards Iowa could occur the financial Panic of 1873 (brought about through the failure of Jay Cooke's banking firm) stopped all work.

This event also brought an end to M&StL's brief control under the Northern Pacific, which was constructing a Puget Sound transcontinental corridor.

The Falls of St. Anthony in a painting completed by American artist

Albert Bierstadt during the 1880's.

The Falls of St. Anthony in a painting completed by American artist

Albert Bierstadt during the 1880's.After the economy had recovered efforts to reach the Hawkeye State resumed. Crews began south from Merriam in the spring of 1877 and had reached Albert Lea on November 12th where a new connection with the Burlington, Cedar Rapids & Northern Railway (Rock Island) opened.

The point of this continued growth, of course, was not only to provide additional transportation arteries for Minneapolis/St. Paul businesses but also reach new freight customers. In particular was the movement of grain in the production of flour.

However, the M&StL was also handling anything a customer was willing to ship, everything from wheat and oats to nails and butter (along with a various array of less-than-carload traffic).

But as the company's leaders quickly realized, pushing the railroad ever-further into America's Heartland meant irritating much more powerful interests associated with the Chicago & North Western; Burlington; Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (Milwaukee Road); and Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (Rock Island).

This began a cautious approach towards further expansion that, unfortunately, resulted in its failure to reach another notable market.

Over the years there were grandiose talks of opening to Lake Superior, extending to St. Louis, pushing towards Chicago, and even once contemplating following in Milwaukee Road's footsteps to the Pacific coast. However, none ever gained serious traction.

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1 #209 is seen here at the shops in Peoria, Illinois on June 4, 1956. Author's collection.

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1 #209 is seen here at the shops in Peoria, Illinois on June 4, 1956. Author's collection.While prudence was the order of the day, officials realized some type of further growth was necessary if their railroad hoped to remain competitive while continuing to support the Minneapolis economy.

It finally got into Iowa via the small Fort Dodge & Fort Ridgely, an 1879 acquisition. As this small road was building north out of Fort Dodge it was met by the M&StL (through a subsidiary known as the Minnesota & Iowa Southern) at Livermore during the summer of 1880.

The southern end offered a new source of traffic, coal. Although its presence proved only fleeting, for some years mines located within Webster County, Iowa provided additional tonnage.

To access even more seams the railroad continued pushing south of Fort Dodge, eventually reaching Coaltown (later renamed Angus) by December of 1881.

As this was ongoing the railroad launched what it called the "Pacific Extension" that same year. It struck out west from Hopkins and opened to Morton by November of 1882. Through lease of Rock Island's Wisconsin, Minnesota & Pacific the M&StL boasted a nearly 400-mile network with a western terminus at Watertown, South Dakota.

- It formally acquired the Morton - Watertown segment from Rock Island on February 20, 1899. In the end, the CRI&P gave up on the WM&P project.

For a time the M&StL had also operated the other section between Red Wing and Mankato, referred to as its Cannon Valley Division. This too was sold and became part of the Chicago Great Western as of June 1, 1899. -

Minneapolis & St. Louis SD7 #300 (built as #852) is seen here in Peoria, Illinois during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Minneapolis & St. Louis SD7 #300 (built as #852) is seen here in Peoria, Illinois during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.Further construction was curtailed after the company fell into receivership during June of 1888. It was sold on October 11, 1894 and subsequently reorganized as the Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway. At century's end the new company, fresh out of receivership, was again on the move.

New leadership in the form of Edwin Hawley wanted to expand M&StL's territory elsewhere into Iowa. In 1899 it began work on a 158-mile extension from Winthrop to Storm Lake for the purpose of expanding its agricultural base. That same spring construction commenced. After only a year the line officially opened on August 19, 1900.

With two routes now serving Iowa, Hawley sought further growth southward and eastward. To accomplish this he brought in the Iowa Central Railway (ICRy) by becoming its president on June 20, 1900 then added the Des Moines & Fort Dodge (DM&FtD); both roads officially joined the M&StL network as of January 1, 1905.

The DM&FtD served Des Moines and extended northward to Fort Dodge before turning northwesterly as far as Ruthven. Although the M&StL was never able to close the 14-mile gap to Spencer it manage to secure trackage rights over the Milwaukee Road for through service.

The ICRy opened considerably more territory to the Tootin' Louie, extending from Mason City to Albia via Oskaloosa. At the latter town its route turned east where it crossed the Mississippi River and terminated at Peoria, Illinois.

In addition, the ICRy owned the following branches; Hampton - Belmond, Minerva Junction - Story City, Grinnell - Montezuma, and New Sharon - Newton. Altogether, its territory totaled 510 miles.

System Map (1940)

The Modern "Tootin' Louie"

At this point the Minneapolis & St. Louis was mostly complete except for its Pacific Division extension beyond Watertown. The project was launched as the Minnesota, Dakota & Pacific, incorporate on December 18, 1905, with construction beginning the following year.

There were two goals; building to the Missouri River at Le Bleau (171 miles) and branching at Conde with a northwesterly extension to Leola via Aberdeen (57 miles). The new route totaled 228 miles; rails reached Leola on December 21, 1906 with the Le Bleau segment opening the following year.

While the modern M&StL was generally profitable, typically earning a net annual income above $1 million (there were exceptions, such as the immediate post-World War I years and following the Great Depression), it was never able to reach the far away places its early promoters had envisioned.

During these early years its traffic base was considerably diversified (ranging from time freights and general merchandise to lumber and coal) although agricultural products (grains, flour, wheat, corn, etc.) remained unmatched in importance until C&NW's takeover.

Passenger Trains

Because the Minneapolis & St. Louis served few major cities it did not operate extensive passenger services. Its peak years could be regarded as the 1880s when in 1888 40% of its annual revenue came directly from ticket sales.

However, through the 1920's patrons continued to account for nearly 25% of its yearly earnings. Its most well-known train was the North Star Limited, which operated between Minneapolis and Albia, Iowa. From there it was transferred to the Wabash and continued on to St. Louis operating with through sleepers, chair cars, and a diner.

But even the North Star was short-lived, surviving only until May 30, 1935 when the depression caused its cancellation. With the development of the gas-electric railcar ("Doodlebug") the M&StL began using it extensively due to the railroad's declining patronage and the car's inexpensive nature.

It also experimented with the Budd Company's similar RDC (Rail Diesel Car) in the late 1950's for Minneapolis-Des Moines service but found them of little use. Passenger service was formally discontinued between July 20-21, 1960 when trains #13 and #14 made their final runs.

The company continued enjoying sustained success until the onset of World War I and nationalization through the United States Railroad Administration made effective at noon on December 28, 1917. The directive was ordered by President Woodrow Wilson in response to fears of national gridlock.

Unfortunately, the government did no better at maintaining fluid operations than the private sector; during this time equipment was rundown and infrastructure inadequately maintained to meet the crushing demand.

This resulted in many railroads' (including M&StL's) operating ratio (operating expenses as a percentage of revenue) ballooning from the 60's to the 90's with some even topping 100%. Through the Transportation Act of 1920 the industry was finally returned to private ownership on February 28th.

Unfortunately, for the M&StL (and most other carriers) its network was worn out. This had been an issue for the Tootin' Louie even prior to the war as it did not have the necessary funding to correct the problem.

Despite enjoying record livestock traffic in 1922 (to the tune of 291,713 tons), and strong traffic overall, the railroad was forced into receivership again on July 26, 1923 (once a lucrative traffic source livestock had all but evaporated by the 1950's with only 1,117 carloads moved in 1959).

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1's layover in Minneapolis during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1's layover in Minneapolis during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.The stock market crash on October 24, 1929 initially had little effect since the company was already under bankruptcy protection. However, as the depression settled in the matter became critical. Mr. Hofsommer's book notes that in 1923 its freight tonnage had peaked at 7.3 million.

In 1929 this number had declined only slightly to just under 7 million. However, as the depression took hold tonnage shrank to just 3.6 million. The passenger numbers were no better. In 1915, a record 2,574,797 travelers were served but by 1932 this had fallen to only 150,017.

Such poor results not only spoke to the era's unfavorable business environment but also the M&StL's alarming situation. This issue, coupled with its small service area, dilapidated infrastructure, and light traffic density initiated talks of liquidation.

By 1935 a plan had been drawn up whereby the Burlington, Great Northern, Chicago & North Western, Rock Island, Milwaukee Road, and Chicago Great Western would each purchase various segments. Ultimately, the Interstate Commerce Commission proved a saving grace when it ruled against dismemberment in June of 1938.

One issue was clear, the railroad needed to pare down its network if it wanted to survive. With new leadership in the form of Lucian C. Sprague (who had arrived on January 1, 1935) some 126 miles were identified as redundant.

The ICC did not grant every request but much of the trackage was eventually let go including:

- St. Benedict - Algona (Totaling 8 miles, the last train ran this segment on April 3, 1936. The line was further cutback from Corwith to St. Benedict in April of 1948.)

- Spencer - Storm Lake (Totaling 36.9 miles, the last train ran ran a few weeks later on April 25th.)

- The original main line south of Fort Dodge was largely removed by 1938. (A little over 36 miles.)

- Grinnell - Montezuma (13.6 miles, the last train ran on August 1, 1936)

It all added up to about 94 miles although more cutbacks would occur in the coming years. The railroad had been reducing its network as early as 1924 when the segment from Akaska to Le Bleau was abandoned. The small town, once a bustling livestock center, had withered to the point it no longer held any strategic value.

Only a year later the ICC authorized another cutback, removing a 10-mile section in Iowa between State Center and Van Cleve (The final train ran this segment on August 22, 1925 and a further retrenchment occurred in 1939 when 6.8 miles was pulled up to Laurel.).

An aging Minneapolis & St Louis RS1, #215, soldiers on in service in Minneapolis, circa 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

An aging Minneapolis & St Louis RS1, #215, soldiers on in service in Minneapolis, circa 1963. American-Rails.com collection.As the Pacific Division's importance dwindled, further abandonments were carried out. At first, the M&StL wanted to remove everything west of Watertown but eventually settled on just the Conde - Akaska section (103 miles) and the Aberdeen - Leola spur.

The former saw its last run on November 18, 1940 while efforts to abandon the latter eventually failed. As this was all ongoing, Sprague's leadership and the blitzkrieg of traffic brought about by World War II finally helped the railroad escape receivership.

After more than twenty years mired in bankruptcy it was finally reorganized on December 1, 1943. Between this point and the war's end (1945) the M&StL enjoyed a healthy net income of $5.4 million (total) despite rising labor costs.

Its final decade as an independent entity was actually a relatively prosperous period. In an effort to further streamline operations the company purchased its first diesel road-switchers in 1943 when American Locomotive RS-1's arrived in 1944.

This had followed a batch of switchers acquired in the 1930's while a trio of gasoline-powered rail cars, "Doodlebugs," were ordered from General Electric in 1929 (GE-1 through GE-3).

More diesels were acquired through the 1940's and 1950's until steam had been retired completely by January of 1951 (the "official" end of steam occurred in September of 1949 when 4-6-2 #502 made a special appearance at the Chicago Railroad Fair that year).

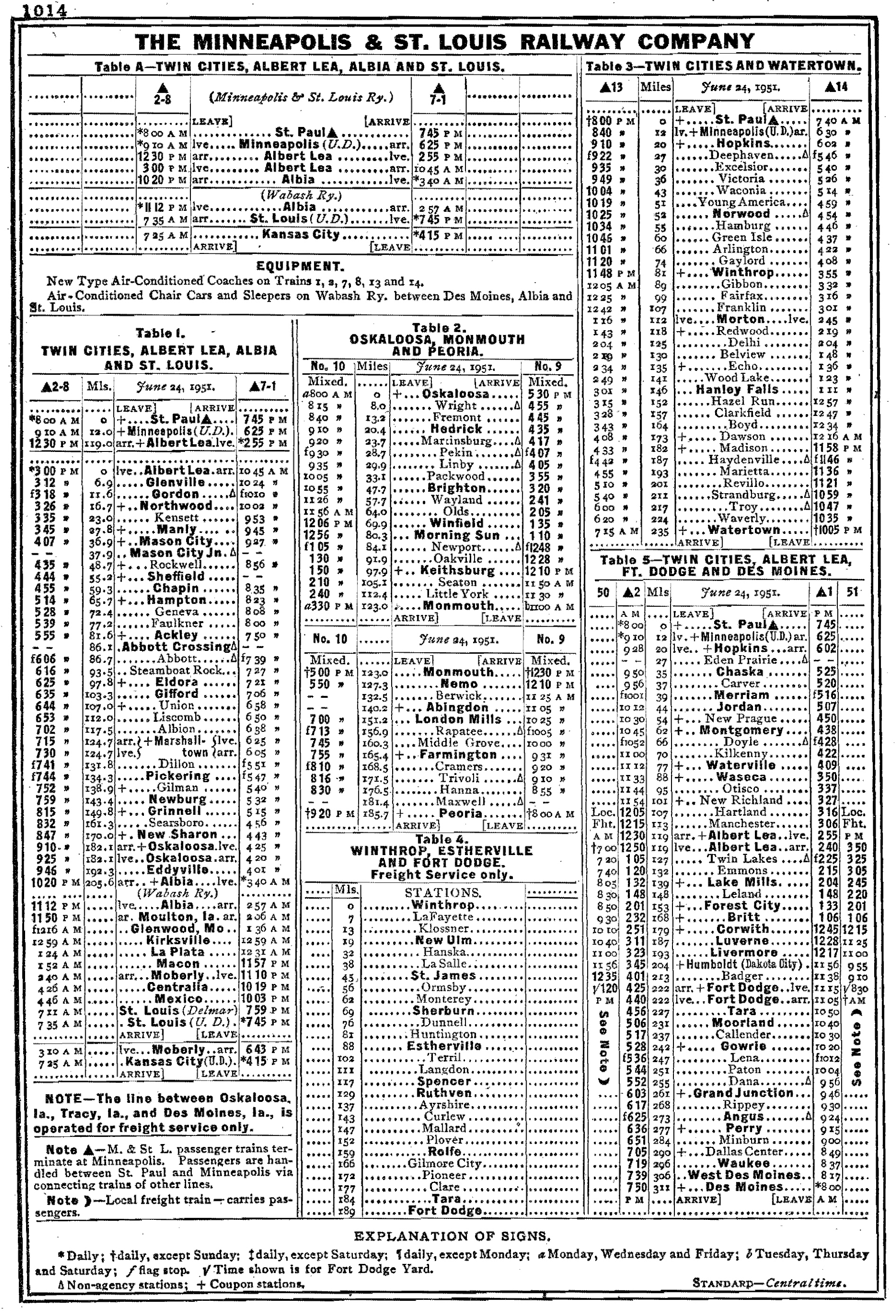

Timetables (1952)

Sprague had remained president through this time; he was a good railroader who tried his best to run a tight ship and treat employees fairly.

There more even more abandonments after the war when the following occurred; 5.25 miles between Fosterdale - Tracy were let go in 1949; 9.5 miles between Laurel and Newburg stopped running in 1950; Denhart - Corwith (4.3 miles); and Roland - Story City (5.2 miles) also in 1952.

Unfortunately, Sprague could not anticipate what would occur in 1953 when a group led by Ben Heineman began a battle for control of the Minneapolis & St. Louis. The proxy war lasted through 1954 as Heineman argued the company's current leadership was ineffective.

During a special meeting held on May 11th that year Heineman received 311,479 of the 589,229 shares available and was declared the winner. While he was never considered a great railroader he did a decent job at the M&StL during his brief stint, maintaining profits above $1 million annually.

He purchased new technology in the form of IBM machines to improve accounting efficiency and launched an ambitious plan to transform the M&StL into a much stronger player in the Midwestern market. His idea involved acquiring the 242-mile Toledo, Peoria & Western with which the railroad interchanged at Peoria.

It was not a particularly glamorous system but did connect with numerous eastern and western carriers across Illinois. Heineman's grand plan, as Mr. Hofsommer points out, was to form a sort of gigantic Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railway that would have completely bypassed congested Chicago.

The M&StL utilized a steam and diesel locomotive roster of mostly medium-sized power. For instance, the railroad's largest steam locomotives were only 2-8-2 Mikados and its heaviest diesel locomotives were six-axle EMD SD7s (the only two six-axle diesels it ever operated).

However, given the railroad's geography and size this type of power performed quite well for its needs. The M&StL's final order of diesel locomotives was a batch of 15 EMD GP9s delivered in 1958.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH-660 | D-939 | 1939 | 1 |

| HH-1000 | D-539 | 1939 | 1 |

| S2 | 102 | 1941 | 1 |

| RS1 | 146, 244, 246, 346, 446, 546-547, 645-646, 744-746, 751, 845-846, 849, 851, 944-946, 948-951, 1044, 1046, 1048-1050, 1144, 1148-1150, 1249-1250 | 1944-1951 | 35 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | D-145, D-340 | 1940, 1945 | 2 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| NW2 | D-139 | 1939 | 1 |

| SC | D-438 | 1938 | 1 |

| NW1 | D-538, D-738 | 1938 | 2 |

| SW | D-838 | 1938 | 1 |

| F2B | 147B | 1946 | 1 |

| F7A | 150A-151A, 150C-151C, 250A, 250C, 350A, 350C | 1949-1950 | 8 |

| F3A | 248A, 248C, 348A, 348C, 448A, 448C | 1948 | 6 |

| FTA | 445A, 445C, 545A, 545C | 1945 | 4 |

| FTB | 445B, 445B | 1945 | 2 |

| GP9 | 600-608, 700-713 | 1956-1958 | 23 |

| SD7 | 852, 952 | 1952 | 2 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | D-149, D-742, D-842 | 1942, 1948 | 3 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A1-11, A1-13 | Switcher | 0-4-0/T |

| B1 Through B3 (Various) | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| D6 Through D9 | >American | 4-4-0 |

| F1 Through F5 (Various) | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| G1 Through G7 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| H1 Through H6 (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| K1 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| M1, M2 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1 #446 and SD7 #952 are seen here on February 2, 1955. Location not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.

Minneapolis & St. Louis RS1 #446 and SD7 #952 are seen here on February 2, 1955. Location not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.Chicago & North Western Takeover

The idea was originally proposed by noted executive John Barriger III who had envisioned the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville (Monon) and Chicago & Eastern Illinois as part of this merged system.

It was a fascinating concept that may have proved quite successful but much larger interests, notably the Santa Fe and Pennsylvania, as well as TP&W's private ownership, fought against the takeover and the idea died.

After Heineman left for the Chicago & North Western in 1956 (Where he carried out a similar fight but this time opposition quickly capitulated and he assumed the chairmanship/chief executive role of that company on April 1. He tried a similar tactic when battled ensued for the Rock Island during the 1960's/1970's but was unsuccessful in this attempt.) it was not long before he returned, in a sense, as the C&NW formally acquired the Minneapolis & St. Louis in 1960.

Through the end the Peoria Gateway was a profitable corporation. During its last five years, 1954-1959, it enjoyed an average annual net income (after taxes) of more than $1.7 million (by comparison, a disheveled Chicago & North Western carried annual net losses of nearly $886,000).

The merger process was quick as the Minneapolis & St. Louis officially disappeared after October 31, 1960. In a sense, the takeover proved hostile as incoming C&NW personnel had no interest in how things had been done previously. As one former M&StL employee stated, "They run a railroad a lot different than we did, believe me."

Despite the initial financial leverage M&StL provided, it wasn't long before the owner began abandoning segments of the railroad. This process continued through the 1990's and today only a few, scattered segments are still in service.

Recent Articles

-

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist…