Northern Central Railway: PRR's Baltimore-Harrisburg Line

Published: November 15, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Northern Central Railway has worn many faces over two centuries: ambitious antebellum trunk line, Civil War lifeline, proud Pennsylvania Railroad main line, and finally a quiet rail-trail and heritage railway threading through farms and small towns. Its story is a microcosm of American rail history, from canal rivalry and iron rails to interstates, bankruptcies, and preservation.

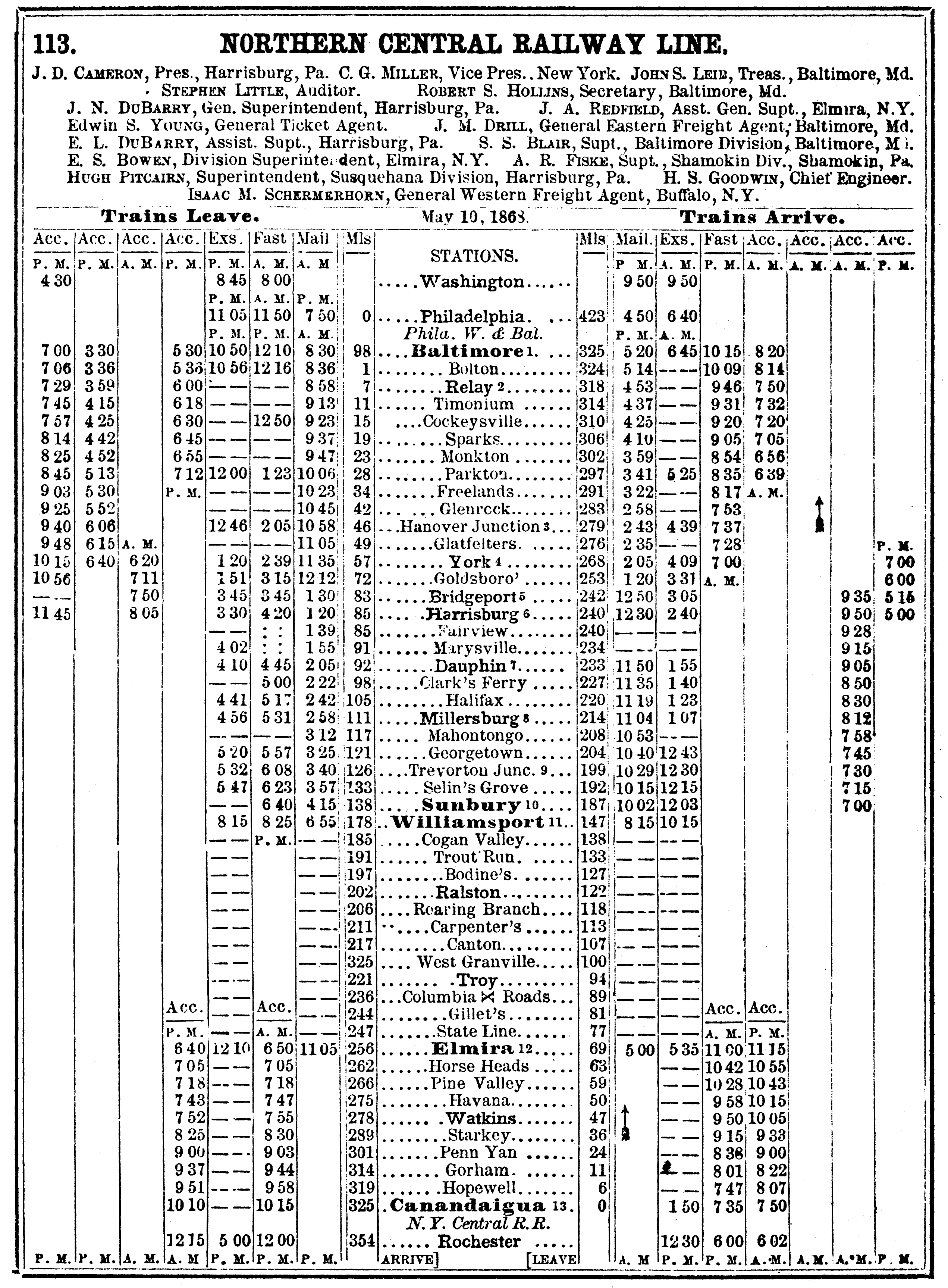

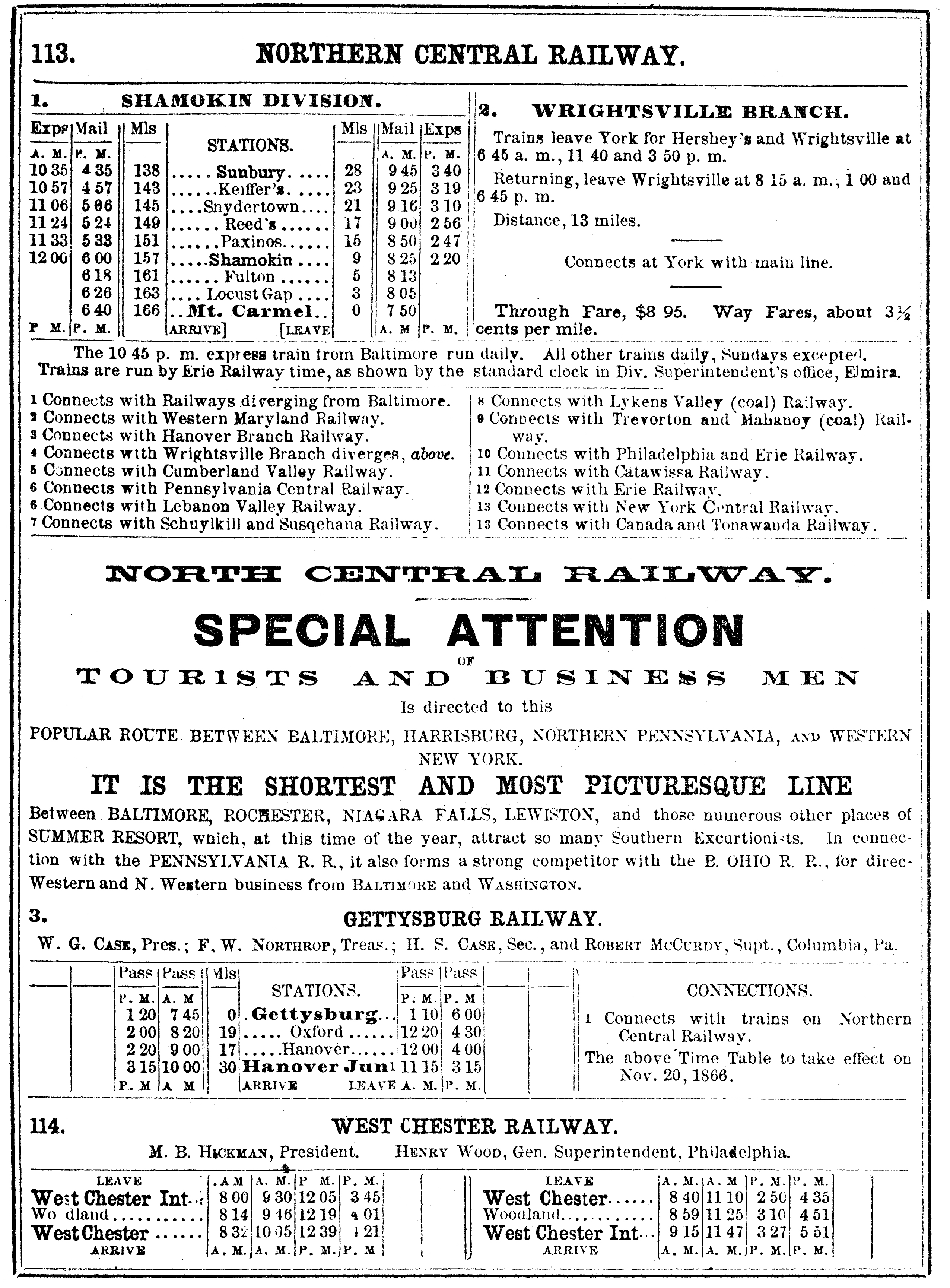

An 1868 timetable of the Northern Central Railway from the June, 1868 edition of "Travelers Official Railway Guide."

An 1868 timetable of the Northern Central Railway from the June, 1868 edition of "Travelers Official Railway Guide."Origins: Linking Baltimore with the Susquehanna

The Northern Central’s roots stretch back to the late 1820s, when merchants and farmers in York County, Pennsylvania, grew frustrated with the cost and difficulty of shipping goods to Philadelphia. They saw opportunity in Baltimore, which was anxious to tap interior trade and compete with both Philadelphia and the newly chartered Baltimore & Ohio.

To reach this trade, businessmen in Baltimore secured a charter for the Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad (B&S) on February 13, 1828. The line was envisioned to run from Baltimore northward toward York Haven on the Susquehanna River.

Construction crept out of the city during the 1830s, reaching such points as Timonium and eventually crossing into Pennsylvania. But politics complicated everything: Pennsylvania, worried about protecting its own canals and railroads, insisted that any line within its borders be chartered under its own laws.

The resulting patchwork of connecting companies became the building blocks of the future Northern Central:

- Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad

- York & Maryland Line Rail Road, incorporated in 1832 to carry the line north from the state line into York

- York & Cumberland Railroad, extending northward toward the Susquehanna

- Susquehanna Railroad, chartered in 1851 to run up the east bank of the river to Sunbury and beyond.

By the early 1850s, Baltimore had invested heavily in the B&S and its affiliates. The city even forgave some loans on the condition that the line be completed to Sunbury and a new, better harbor connection be built. Meanwhile, safety and capacity concerns were growing. A horrific head-on collision between a holiday excursion and a local train on July 4, 1854, illustrated the dangers of single-track operation and pushed officials toward a double-track main line.

In 1854, these separate companies were formally consolidated into the Northern Central Railway (NCRY). The new company inherited not only track but also heavy debts and engineering challenges: steep grades, sharp curves, and numerous bridges along the Susquehanna valley. Using an initial stock issue of about $8 million, later supplemented by additional funding, the NCR pushed ahead. By August 1858, the railroad had bridged the Susquehanna near Dauphin and reached Sunbury, creating a continuous route from Baltimore to central Pennsylvania.

From this point forward, the Northern Central was more than just a regional road. It was a true trunk line, linking Baltimore’s harbor with the coal fields, industries, and rail connections of the Susquehanna Valley.

An 1868 timetable of the Northern Central Railway from the June, 1868 edition of "Travelers Official Railway Guide."

An 1868 timetable of the Northern Central Railway from the June, 1868 edition of "Travelers Official Railway Guide."The Civil War: Lifeline to the Union

On the eve of the Civil War, the Northern Central’s strategic value became obvious to both politicians and railroad men. It provided:

- A north–south axis connecting Washington and Baltimore with Harrisburg, Sunbury, and beyond via connections.

- Direct access to Camp Curtin at Harrisburg, the largest Union training camp in Pennsylvania.

- A relatively protected inland route, compared to lines closer to the coast or the contested border areas.

At the same time, investors worried about the financial risks of owning stock in a railroad likely to become a military target. In 1861, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) purchased a controlling interest in the Northern Central’s stock, gaining both a strategic southern outlet and a competing route to the B&O’s line into Baltimore. From that point until the Penn Central merger in 1968, the Northern Central would operate essentially as a PRR subsidiary.

Troops, supplies, and telegraphs

During the Civil War, the Northern Central became a crucial artery of the Union war effort. It carried:

- Troops moving south from Camp Curtin and other Pennsylvania depots toward Baltimore and onward to Washington.

- Supplies and munitions destined for the Army of the Potomac.

- Wounded soldiers being evacuated north after battles.

The line’s importance made it a target. Confederate cavalry, notably under Jubal Early during the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign, raided and destroyed bridges, track, and telegraph lines along the Northern Central in an effort to disrupt Union communications and logistics. The PRR and NCRY, backed by the federal government, scrambled to rebuild, often restoring service in a matter of days.

Abraham Lincoln

The Northern Central is forever tied to Abraham Lincoln. In November 1863, Lincoln rode the line from Baltimore through Hanover Junction on his way to deliver the Gettysburg Address. Stations such as Hanover Junction and New Freedom became brief waypoints on that historic trip.

Less than two years later, in April 1865, the Northern Central again bore Lincoln—this time in death. The Lincoln funeral train traveled north from Baltimore to Harrisburg over the NCR tracks as it began its long journey to Springfield, Illinois. Contemporary accounts describe crowds lining the right-of-way, standing silently as the train rolled by through the river valley.

The Civil War era cemented the Northern Central’s reputation as both a strategic military corridor and a symbolic link in the story of the Union.

A Key PRR Main Line

Under Pennsylvania Railroad control, the Northern Central evolved from a regional road into a first-class main line between Baltimore and Harrisburg. By the early 20th century, the PRR had double-tracked the route and installed block signals, turning the line into a high-capacity corridor for both freight and passenger traffic.

Double track and heavy traffic

From Baltimore north through places like Lutherville, Parkton, New Freedom, York, and on to Harrisburg, the Northern Central became a double-tracked, block signaled main line. The line carried:

- Local freight: flour, paper, milk, coal, farm products, and less-than-carload shipments serving the small towns and industries along the route.

- Through freight: While much long-haul freight eventually favored the PRR’s electrified Port Road Branch along the Susquehanna, the Northern Central still handled significant traffic.

Local passenger service included the well-known “Parkton Local”, a commuter train shuttling between Baltimore’s Calvert Street Station and Parkton, Maryland. These trains helped knit the northern suburbs into the city’s orbit and were a fixture on the timetable into the 1950s.

The Liberty Limited and the "Blue Ribbon Fleet"

The PRR’s prestige shone brightly on the Northern Central. One of its premier named trains, the Liberty Limited, was part of the railroad’s famed “Blue Ribbon Fleet” of high-quality passenger services. Introduced in 1925, the Liberty Limited ran between Washington, D.C., and Chicago, via Baltimore, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh.

Between Washington and Baltimore the train used PRR’s Washington–Baltimore line; between Baltimore and Harrisburg it raced over the Northern Central’s double track. From there it continued across Pennsylvania’s main line toward Pittsburgh and westward to Chicago.

With its modern sleeping cars, dining service, and fast schedule—originally about 19 hours end-to-end—the Liberty Limited symbolized the PRR’s ambition to offer first-class service on par with, or better than, rival roads like the B&O and New York Central.

Other PRR name trains also used the Baltimore–Harrisburg route for portions of their journeys, including through sleepers to Buffalo, Toronto, St. Louis, and even Houston via connections. For decades, the Northern Central was not merely a branch but an integral part of PRR’s national passenger system.

Decline, Damage, and Abandonment

Despite its strong position, the Northern Central could not escape the pressures that beset American railroading after World War II. Several forces converged to undermine the line.

Competition and rationalization

From the late 1940s onward, the rise of automobiles and highways drew away short-haul passengers, while trucks increasingly diverted freight. The completion and improvement of U.S. 111 and later Interstate 83 in the 1950s and 1960s offered motorists a fast parallel route between Baltimore and Harrisburg.

The PRR, facing falling passenger volumes and rising costs, began trimming services:

- The Parkton local commuter trains ended in 1959.

- The line, once entirely double-tracked, was gradually reduced to single track in many segments to cut maintenance expenses.

- Some premium long-distance services were discontinued or rerouted.

Although the Liberty Limited itself survived into the early 1950s before being downgraded and eventually discontinued, the trend was clear: the age of the named trains was passing, and the Northern Central lost much of its prestige traffic.

Penn Central and the final blow

In 1968, the PRR merged with the New York Central to form the ill-fated Penn Central Transportation Company. The new system inherited duplicate routes, heavy debt, and a regulatory framework that made it hard to shed unprofitable lines. In this environment, the Northern Central’s future dimmed further. Traffic continued to decline, and maintenance lagged.

Then came Hurricane Agnes in June 1972. Torrential rains and flooding devastated many Northeastern rail lines. Along the Northern Central, bridges, track, and roadbed were heavily damaged—especially between York and Baltimore. Contemporary accounts note multiple washouts, destroyed bridges, and sections of roadbed simply scoured away.

Penn Central, already bankrupt since 1970, concluded that rebuilding the line south of York was not economically justified, particularly with parallel routes and highway competition. Passenger service had largely disappeared by this point—Amtrak, formed in 1971, routed most of its Washington–Chicago and Harrisburg services over other PRR main lines. The once-proud Northern Central main line slipped into suspended operation and then formal abandonment in stages during the 1970s.

When Conrail was created in 1976 to assume many bankrupt Northeastern rail properties, portions of the Northern Central passed to the new company. Some segments in Pennsylvania remained active for freight; much of the damaged Maryland trackage, though, never saw heavy trains again.

From Main Line to Rail Trails and Heritage Railway

Although the main-line railroad disappeared in the 1970s, the Northern Central’s physical corridor proved too valuable to simply vanish. Over time it found new life in several forms: urban transit, rail trails, and a heritage railroad that actively interprets its history.

Light rail in Baltimore

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a portion of the former Northern Central between Baltimore and Cockeysville was rebuilt and electrified for the Baltimore Light RailLink system. The new double-tracked light rail follows the old right-of-way in many places, and for years local freight trains also operated at night by agreement with the Maryland Transit Administration.

Though the heavy PRR trains are gone, this reuse keeps the southern end of the corridor functioning as a transportation artery—much as planners envisioned nearly two centuries ago.

Torrey C. Brown Rail Trail and York County Heritage Rail Trail

North of Cockeysville, different preservation path emerged. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources secured much of the abandoned right-of-way and, beginning in the early 1980s, converted it into what is now the Torrey C. Brown Rail Trail (originally the Northern Central Railroad Trail).

The trail runs nearly 20 miles from Cockeysville to the Mason–Dixon Line, closely following the Gunpowder River and passing old stations like Monkton. It opened fully to the public in 1984 and today forms a popular, largely level pathway for cyclists, joggers, equestrians, and walkers.

Across the state line in Pennsylvania, the former NCR corridor continues as the York County Heritage Rail Trail. Pennsylvania acquired the line between York and New Freedom in 1973, only a year after Hurricane Agnes, and by the 1990s the route had been improved into a formal multi-use trail.

Together, the Torrey C. Brown and York Heritage trails form a continuous greenway running roughly from Cockeysville to York, preserving the feel of the Northern Central’s river and farm landscapes even as the rails have largely disappeared.

Northern Central Railway of York: Living history on the rails

Perhaps the most visible heir to the old line is the Northern Central Railway of York, a heritage railroad that operates over a portion of the former NCR in southern York County. Using both steam and diesel power, the operation runs excursions between New Freedom, Hanover Junction, Seven Valleys, and beyond, closely paralleling the Heritage Rail Trail.

Originally launched under the name Steam Into History, the organization rebranded as the Northern Central Railway of York to emphasize its link with the historic main line. Its excursions often highlight:

- The Civil War role of the line, including events at Hanover Junction, a key junction during the Gettysburg Campaign.

- Abraham Lincoln’s journeys to Gettysburg and the passage of his funeral train.

- The day-to-day life of small communities that grew up along the railroad.

The railroad uses period-style coaches—such as the “Abraham Lincoln” car designed to evoke 19th-century interiors—and operates a replica 4-4-0 #17, named the "York" (completed in 2013), to recreate the atmosphere of steam-era travel.

Passengers today can look out from open-air cars or coach windows and see the same fields, farmsteads, and small towns that Civil War soldiers once saw, while cyclists and joggers pace the train on the adjacent trail. It is a vivid, living reminder that what is now a recreational landscape was once one of the most important rail corridors in the Mid-Atlantic.

Legacy of the Northern Central

Although the Northern Central Railway formally disappeared as a corporate entity decades ago, its legacy lingers in several important ways:

- Strategic Rail Geography – By tying Baltimore to the Susquehanna Valley and central Pennsylvania, the NCR helped shape trade patterns, industrial growth, and even military logistics from the 1830s through World War II.

- Civil War and Lincoln Connections – The line’s role in moving troops and supplies, its susceptibility to Confederate raids, and its association with Lincoln’s Gettysburg trip and funeral train give it a powerful place in Civil War memory.

- PRR Main-Line Status – As a double-tracked, heavily signaled corridor, the Northern Central was for decades a critical PRR main line, hosting both hard-working locals and top-tier trains like the Liberty Limited—part of the railroad’s famed Blue Ribbon Fleet.

- Transition and Adaptation – The line’s story illustrates postwar shifts in American transportation: highways and air travel undercutting passenger service, rationalization under Penn Central and Conrail, and eventual abandonment after natural disaster.

- Rebirth as Trails and Heritage Rail – Today, the corridor thrives in new forms: as light rail in Baltimore, as the Torrey C. Brown and York County Heritage rail-trails, and as the Northern Central Railway of York with its steam and diesel excursions. These reuses preserve both the physical pathway and the stories associated with it.

From the moment the Baltimore & Susquehanna was chartered in 1828, through the thunder of troop trains and the elegance of the Liberty Limited, to today’s cyclists, joggers, and heritage trains, the Northern Central has remained a vital thread in the landscape. The steel rails that once echoed with PRR Pacifics and heavy freight may be mostly gone, but the route continues to carry what railroads have always moved best: people, stories, and connections across time.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.