Penn Central Railroad: Map, History, Logo, Photos, Roster

Last revised: October 15, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Penn Central, officially known as the Penn Central Transportation Company, spawned the modern-day mega railroad although the

ill-fated system also marked the industry's low point.

When the PC collapsed in 1970 it began a long decade of uncertainty, leaving many to wonder if the railroad was an obsolete mode of transportation.

The dark days then, building since the immediate postwar years, proved a turning point. It was a wake-up call to the government that assistance was desperately needed not only to save the Northeast but also the industry itself.

Passenger trains of all types were no longer a viable business model; if these were to continue the feds or states must subsidize the service.

In addition, suffocating regulations, a plague throughout the 20th century, helped doom Penn Central. The creation of Conrail also brought about change in this area as deregulation freed companies to set freight rates and more easily abandon or sell unprofitable corridors.

Today, many key Penn Central routes remain in use under Amtrak, CSX Transportation, and Norfolk Southern while numerous branches are operated by short lines.

Photos

Penn Central E8A #4290 has train #54, the "Pennsylvania Limited," on Horseshoe Curve on a snowy February 23, 1969. Roger Puta photo.

Penn Central E8A #4290 has train #54, the "Pennsylvania Limited," on Horseshoe Curve on a snowy February 23, 1969. Roger Puta photo.History

When I was in college a few professors highlighted the collapse of Penn Central.

The lectures were interesting albeit too brief for someone who enjoyed railroad history. At the time, Rush Loving, Jr.'s, "The Men Who Loved Trains," had not yet been published.

If so, I am sure it would have been required reading. Today, many educators, at both the high school and collegiate levels, have likely done this very thing.

Loving's title not only provides an in-depth study of the company's failings but also the intricate politics which pervade large corporations.

Penn Central GG1s have a freight in tow through Zoo Junction in Philadelphia on August 7, 1974. Doug Kroll photo.

Penn Central GG1s have a freight in tow through Zoo Junction in Philadelphia on August 7, 1974. Doug Kroll photo.It it is an excellent book vividly illustrating how arrogance can destroy even the most powerful companies. While hubris was a serious problem at Penn Central there were many other factors leading to its downfall. Its creation can be traced back to the end of World War II.

The industry had experienced a resurgence after the lean years of the 1930s and believed these problems were far behind them following the war.

The mighty Pennsylvania Railroad should have recognized the ominous signs. It lost money for the first time in its fabled history during 1946 but continued to spend millions on new passenger equipment while carrying out few modernization or cost-cutting initiatives.

The New York Central was somewhat more cautious. The company had never been as profitable as the PRR but was still regarded as one of the most powerful in the nation.

Penn Central RS3 #5318 (ex-New York Central #8318) pulls a transfer caboose along an undisclosed highway (not listed on the listed) in July, 1973. American-Rails.com collection.

Penn Central RS3 #5318 (ex-New York Central #8318) pulls a transfer caboose along an undisclosed highway (not listed on the listed) in July, 1973. American-Rails.com collection.It was widely recognized by the general public for its glamorous passenger trains, notably the 20th Century Limited, and high quality of service. By the 1950s the NYC was struggling and nearly broke.

The company's board realized change was needed and brought in Alfred Perlman. After taking the helm in 1954 he quickly turned around the Central's fortunes by hiring young, innovative new managers; completed dieselization; built classification yards; and introduced creative marketing schemes such as Flexi-Van service (the trains themselves were known as Super Vans).

This latter idea was far ahead of its time, the first successful application of Container-On-Flat-Car service (or COFC).

Logos

While Perlman's work greatly helped its future remained uncertain as an independent carrier. The merger movement was stirring as systems attempted to cut costs and streamline operations in the face of declining traffic and strict regulations.

It was a PRR subsidiary, the Norfolk & Western, which ironically kicked off the modern merger movement by acquiring rival Virginian in 1959. It then purchased a handful of other roads during the 1960s including the Wabash, Nickel Plate, and Akron, Canton & Youngstown.

Penn Central U25Bs #2685 and #2674 lead a southbound Erie Lackawanna freight through North Tonawanda, New York on August 5, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.

Penn Central U25Bs #2685 and #2674 lead a southbound Erie Lackawanna freight through North Tonawanda, New York on August 5, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.In addition, it held stakes in the Erie Lackawanna and Delaware & Hudson for a time. The PRR's situation became precarious; despite its outward appearance the company was, essentially, broke. It launched informal merger talks with the NYC during September of 1957, a moved that surprised many outsiders.

It seemed impossible two of the nation's largest railroads, and fiercest rivals, could merge. Perlman knew his railroad needed a partner but not the PRR.

While he had no insider information, Central's head man was very suspicious that the so-called "gold-plated" Pennsylvania Railroad was a house of cards ready to collapse.

Penn Central E7A #4006 and other power at Michigan Central Station, circa 1969. American-Rails.com collection.

Penn Central E7A #4006 and other power at Michigan Central Station, circa 1969. American-Rails.com collection.He also did not believe the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), governing body of the industry, would ever approve a union that would monopolize the Northeast.

Instead, In 1959, he began courting the Chesapeake & Ohio and Baltimore & Ohio regarding a three-way merger. The Chessie was quite profitable; like the N&W it enjoyed an endless stream of black diamonds originating from mines in southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky.

As for the historic B&O it was much larger than the C&O but struggled with incessant financial problems. When talks began the B&O was doing somewhat better although its future remained murky.

As Perlman saw it a union would be of great benefit to everyone; the B&O offered new markets, the C&O contained its lucrative coal traffic, and a continued effort of modernization and downsizing would make for an efficient company. In addition, a PRR merger with its now-much larger N&W affiliate would provide balanced competition.

On paper, it seemed like the best outcome with the public interest in mind. Alas, feuding broke out between the leaders of NYC, B&O, and C&O regarding who would head the new company and negotiations fell apart.

Formation

With nowhere else to turn, Perlman relaunched talks with the Pennsy in October of 1961 and during the next few years the prospects of merger were hashed out.

The ICC proceedings worked their way towards completion until finally, and surprisingly, the federal agency approved the marriage in January of 1968.

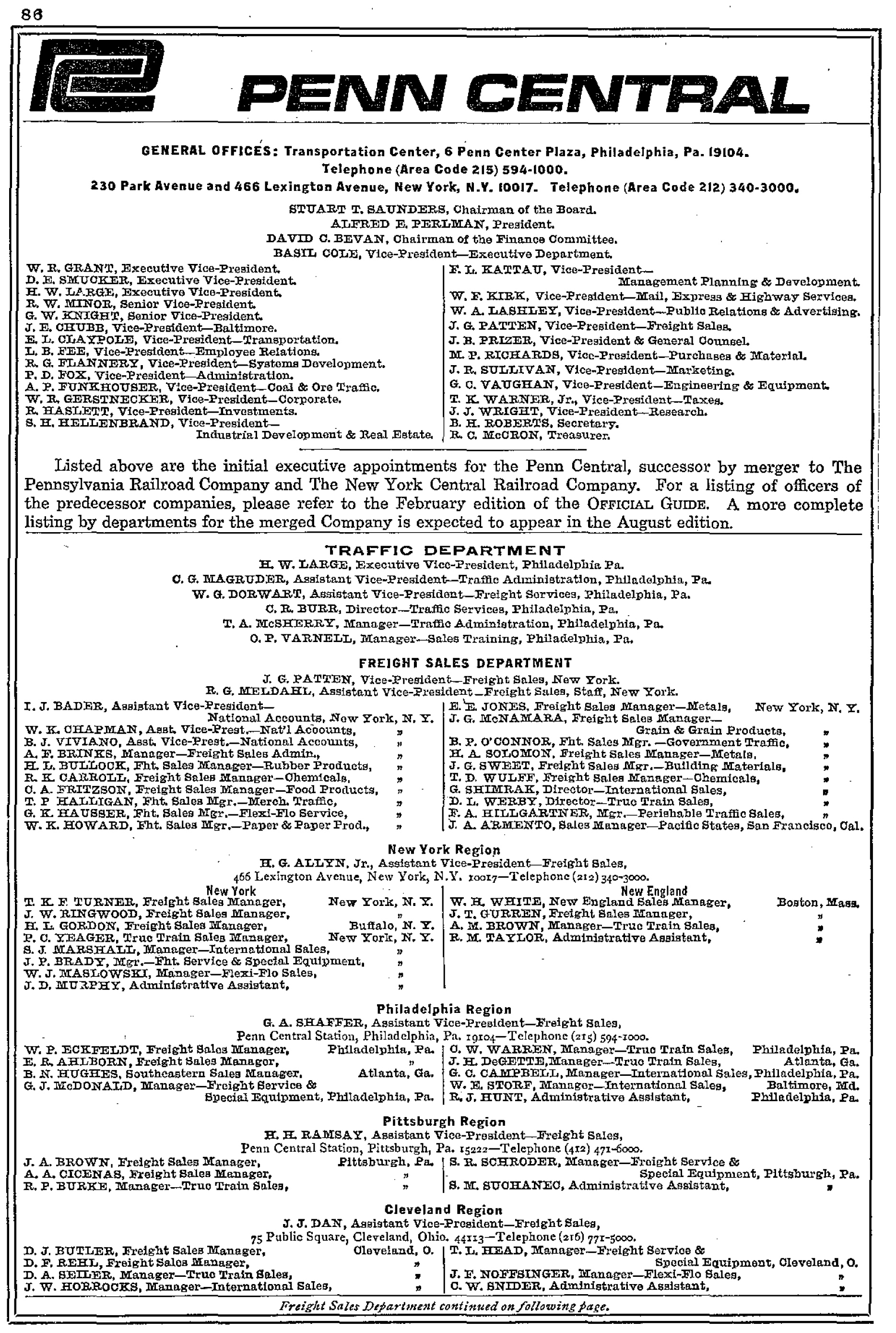

A month later, the Penn Central Transportation Company officially launched on Thursday, February 1, 1968 at 12:01 AM. The new railroad was a monster.

According to David P. Morgan's article, "NYC + PRR, What Does It Mean?," from the January, 1958 issue of Trains Magazine, Penn Central boasted more than 20,000 route miles, contained assets of more than $5 billion, and offered a projected operating revenue of more than $1.7 billion annually.

On the surface these numbers appeared rosy. However, there were many warnings PC was headed for disaster. Its astronomical payroll held more than 180,000 employees, a condition agreed upon by new chairman Stuart Saunders who was brought in from the N&W.

Penn Central locomotives await overhaul outside the shops in Selkirk, New York; April, 1975. American-Rails.com collection.

Penn Central locomotives await overhaul outside the shops in Selkirk, New York; April, 1975. American-Rails.com collection.As Loving argues, Saunders was never a good railroader and understood little regarding operations. However, he was strong in negotiation and appeasement, which wound up working superbly for the unions.

When mergers happen savings are usually derived through the elimination of duplicate routes, terminals, trackage, and redundant positions.

This should have worked to Penn Central's advantage but in an incredible circumstance Saunders gave in to virtually all union demands. The result was predictable, Penn Central became straddled with a ballooned payroll from which it could not escape

- Every employee from both companies was retained

- huge severance packages were promised to anyone fired

- Astoundingly, several-thousand employees were rehired for reasons which had nothing to do with the newly merged company.

Then, there was the operating ratio. This term describes operating expenses as a percentage of revenue. Anything over 80% is extremely high (today's Class I's try to stay in the 60s) and means that for every dollar a railroad earns, at least 80 cents is being devoured by expenses.

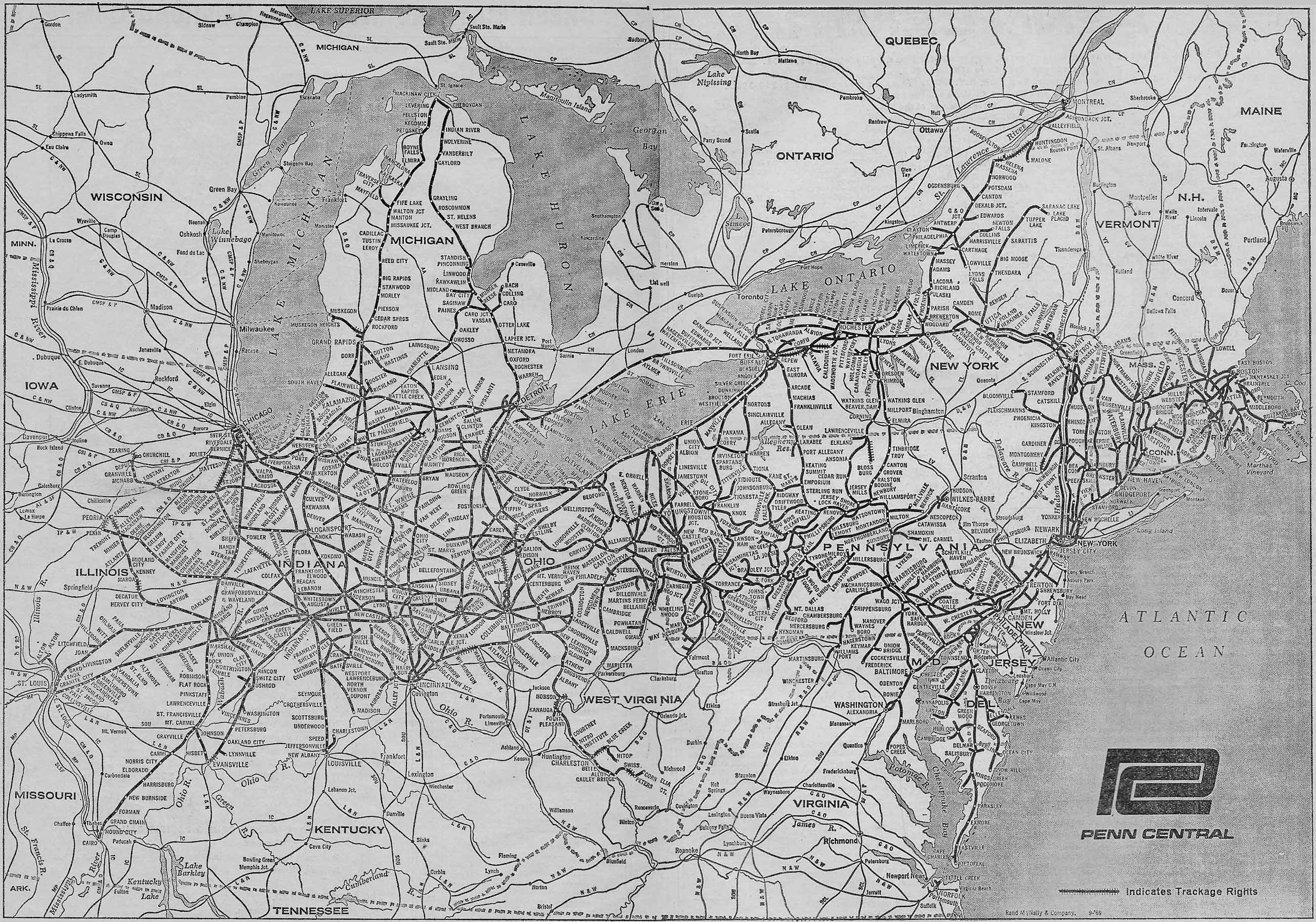

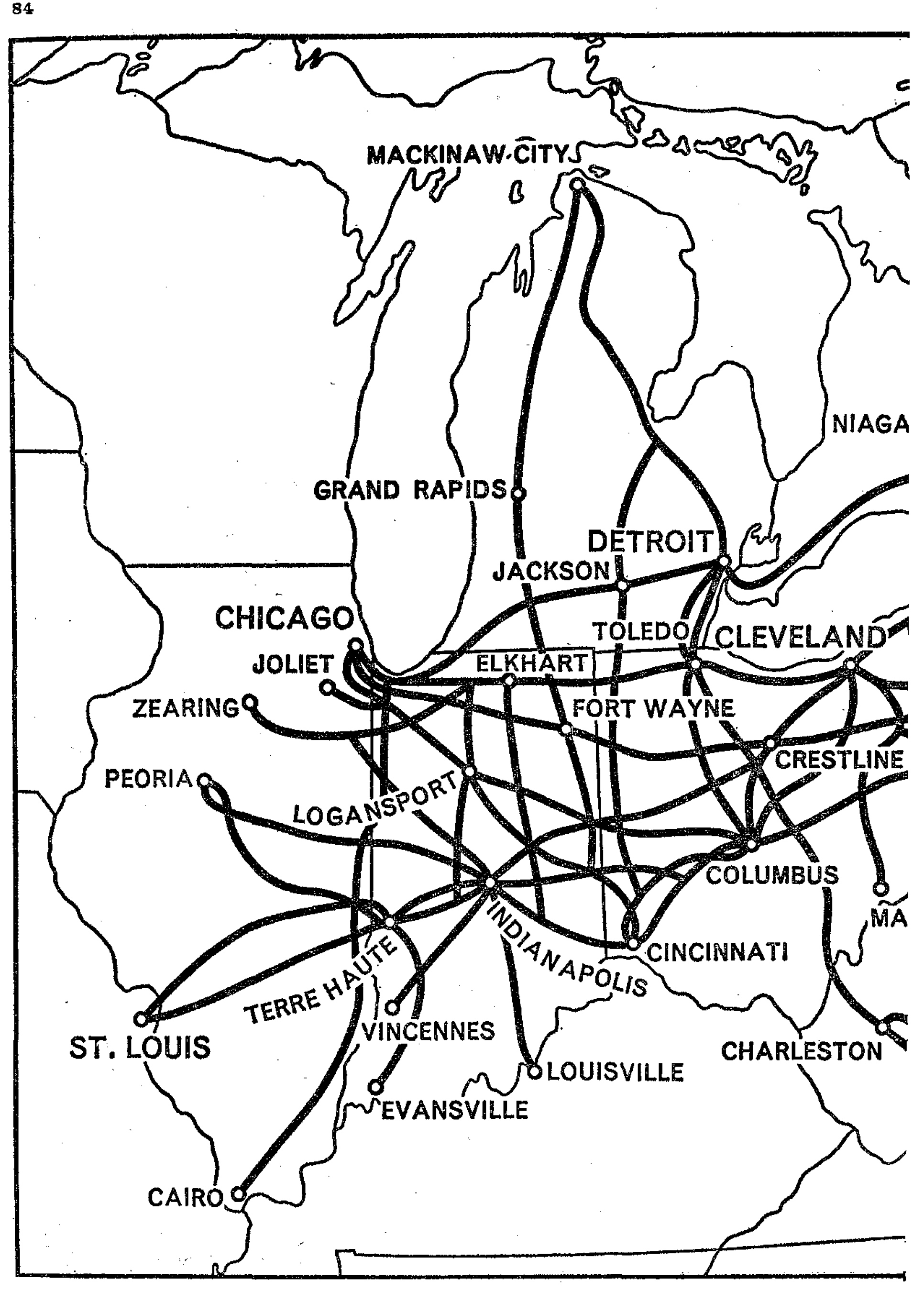

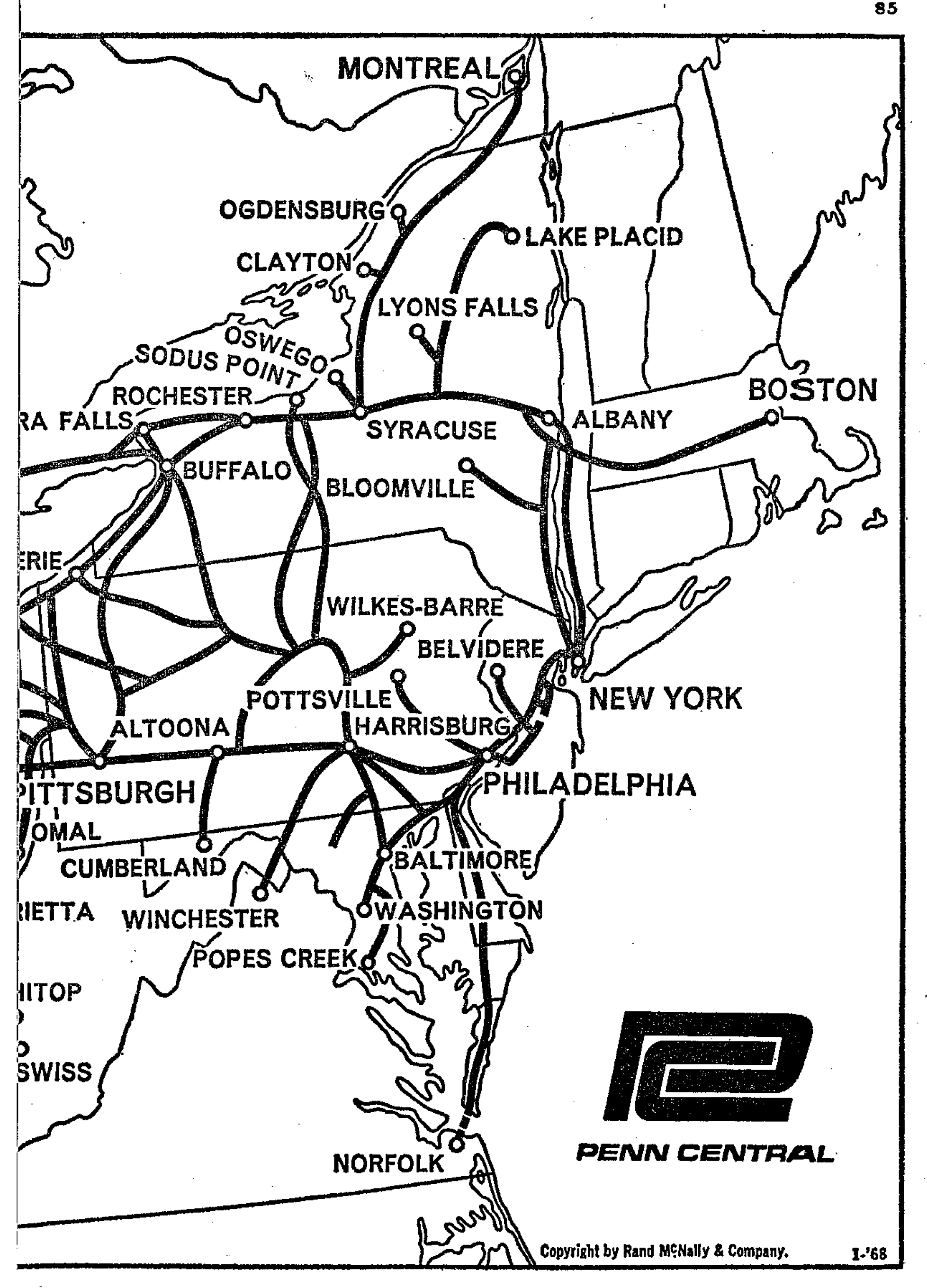

System Map (1969)

With the both the Central and PRR, they carried operating ratios above 81%. Finally, the cash reserves on merger day were slim with just $13 million available (the PRR, alone, required more than three times that amount each day) and spoke of the sickness plaguing each system.

For all of the glaring problems chairman Saunders and president Perlman had attempted initiatives of preparation; to improve operational efficiency they tried to construct massive, new automated freight yards at Selkirk and Albany, New York with another located in Columbus, Ohio.

The New York Central had been implementing such infrastructure upgrades but those at the PRR brushed aside these plans.

Then, the two men worked on an idea to launch an early, computerized system for monitoring and tracing freight cars. Today, this technology is standard and greatly improves efficiency while offering customers the ability to track their product(s). At the time it was innovative stuff.

Penn Central RS3's #5258 and 5282 are southbound with a Niagara Falls to Frontier Yard freight at North Tonawanda, New York on August 14, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.

Penn Central RS3's #5258 and 5282 are southbound with a Niagara Falls to Frontier Yard freight at North Tonawanda, New York on August 14, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.Merger Problems

This time the ICC was the problem; the agency was notorious for dragging its feet on mergers (the Rock Island debacle was unfolding at the same time) and had spent more than six years approving the Penn Central deal; unsure of whether the marriage would happen the men could not invest the capital in the program.

With no other choice they decided to merge each railroad's operating departments from day one. The hope was that over time the situation would work itself out and things would eventually return to normal. Unfortunately, this decision resulted in immediate pandemonium.

As Loving described it: "...None of the classification clerks had been taught the 5,000 new combinations of routings. By the thousands, cars began flowing into the wrong yards."

In one famous incident, former New York Central employees did not know the location of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; even though it was the state capital and an important PRR terminal the city was never served by the NYC.

Former Pennsylvania U25C's, led by #6502 and #6501, at Richmond, Indiana in the early Penn Central era, circa 1969. This corridor was the former PRR's "Panhandle Route" main line to St. Louis. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Former Pennsylvania U25C's, led by #6502 and #6501, at Richmond, Indiana in the early Penn Central era, circa 1969. This corridor was the former PRR's "Panhandle Route" main line to St. Louis. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.So, the car in question was sent to nearby Pittsburgh. A similar incident devastated the Bangor & Aroostook, a small railroad serving northern Maine.

For the BAR, potatoes had long been a primary source of freight; its entire business was lost forever when Penn Central's horrid service lost an entire season's crop at Selkirk Yard in 1969.

A pair of former Penn Central E7A's (ex-PRR) are seen here at South Amboy, New Jersey during the early Conrail era in July of 1978. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of former Penn Central E7A's (ex-PRR) are seen here at South Amboy, New Jersey during the early Conrail era in July of 1978. American-Rails.com collection.The fallout resulted in many farms shutting down and those which remained discontinued rail service. The railroad, itself, was nearly forced into bankruptcy. Things only got worse as incoming "Red Hats" (PRR) and "Green Hats" (NYC) struggled to find common ground.

David Bevan, who came in from the Pennsy, headed Penn Central's financial department. Despite his arrogance, Bevan proved a viable asset. As the situation fell apart his many connections throughout financial and business sectors enabled a continual flow of cash and new loans as Penn Central burned through torrents of cash each day.

At A Glance

In David P. Morgan's article, "NYC + PRR, What Does It Mean?," mentioned above the legendary author and writer painted a foreboding picture of the merger ten years before it was finalized.

He noted the heavy debt of both railroads, their weak earning power, and excess capacity; all three of these issues were only exemplified through the 1960s. The numbers Morgan cites below does not include earnings from the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie, an NYC subsidiary.

His efforts were aided by the PRR's many years of success and vaunted status on Wall Street, which had achieved it an impeccable credit rating. Only those at the very top actually knew how bad the situation was.

As the crisis worsened the railroad missed the lucrative profits of Norfolk & Western; unfortunately, as a condition of the merger PRR had been required to relinquish its ownership in the company.

It seems that whatever could go wrong did. In a further insult, which spoke of the government's feeling towards the industry, the ICC required Penn Central to take in the destitute New Haven.

This regional served southern New England and was an important transportation artery for thousands of commuters traveling between New York and Boston each day. Unfortunately, the New Haven had struggled for years and had been stuck in bankruptcy since 1961.

A pair of tired Penn Central F7As are southbound with a freight at North Tonwanda, New York on August 8, 1973. At this date the railroad was just trying to remain in operation while awaiting some kind of assistance. Doug Kroll photo.

A pair of tired Penn Central F7As are southbound with a freight at North Tonwanda, New York on August 8, 1973. At this date the railroad was just trying to remain in operation while awaiting some kind of assistance. Doug Kroll photo.According to Tom Nelligan's article, "How PC + NH = PC," from the January, 1970 Trains, it added 1,502 additional route miles to PC's network. The New Haven's issue was not only its bankruptcy, debt, and money-losing passenger services.

As Nelligan points out the road's freight revenues were not even profitable. It officially joined Penn Central on January 1, 1969.

For Perlman's part he was constantly trying to improve an impossible situation. Always outspoken, he drew the ire of former PRR brass who never particularly cared for him.

Using Saunders as a pawn, those on the board eventually garnered enough votes to stage a coup d'etat and have Perlman ousted. On August 29, 1969 the board voted Paul Gorman as the company's new president.

Perlman was handed the lame-duck position of vice chairman. After this stint he went on to head the struggling Western Pacific. His abilities as a railroader again shown brightly as he turned around the moribund road before it was purchased by Union Pacific.

Bankruptcy

Unfortunately, Gorman had little more success than Perlman in righting the Penn Central's sinking ship. Bevan tried his best in keeping creditors at bay while acquiring new sources of loans.

In a last ditch effort, Bevan worked his accounting "magic" to prop up worsening numbers through paper profits and other shady practices, otherwise described as "cooking the books."

For the year-end 1969, Penn Central's situation was very grim; the company's railroad arm had lost over $300 million since merger day and was still craving ravenous volumes of cash.

Through the first quarter of 1970 it had lost another $100 million, or more than $1 million a day. The end finally came in June, 1970.

Bevan reported to Saunders that he had exhausted all monetary means; if federal assistance could not be secured bankruptcy was the only option. The railroad nearly secured a $200 million from the defense department at the last minute. However, this stop-gap measure was turned down at the last minute.

A quartet of Penn Central F7's roll past the former PRR depot in Ravenna, Ohio with a string of hoppers during the early 1970s. The author's 1969 Dodge Charger can be seen in the foreground. Jerry Custer photo.

A quartet of Penn Central F7's roll past the former PRR depot in Ravenna, Ohio with a string of hoppers during the early 1970s. The author's 1969 Dodge Charger can be seen in the foreground. Jerry Custer photo.Late in the day on June 21, 1970, Penn Central's board voted to seek voluntary relief from creditors under Section 77 of the federal Bankruptcy Act. The reaction from Wall Street and those in business sectors was shock, no one believed the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad would ever collapse.

It was the largest bankruptcy of its time. In another sign of the times the general public paid scant attention to this enormous and historic business failure. Most were too caught up in the ongoing Vietnam War while those who did notice questioned only if the passenger trains would still run (they did).

The result of Penn Central's fall caused a ripple effect throughout the entire Northeast as other railroads struggled to keep their freight moving. Penn Central's fate was left to bankruptcy judge John Fullam while Jervis Langdon, Jr., an experienced railroader with a career in the industry, became the chief trustee.

Interestingly, Bevan escaped prosecution for his accounting actions, Saunders quietly retired to Virginia, and Paul Gorman hastily left the company finding work elsewhere. After more than three years in receivership, trustees concluded Penn Central problems were too complex for a traditional reorganization.

Diesel Roster

Both the Pennsylvania and New York Central purchased diesels from all of the major builders and many of these interesting models were rolled into Penn Central, which began service on February 1, 1968.

Into the PC era one could find everything from aging RS3s to and FAs to second-generation SD40s and SD45s. While the railroad was an abysmal failure it nevertheless was fascinating from an operational standpoint with first-generation road power still in service well into the 1970s.

The information presented here highlights Penn Central's diesel roster, as well as its remaining fleet of electrics. Since the PRR was the acquiring railroad, PC's fleet was classed per its specifications.

Switchers

| Original Road Number(s) | Second Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7800-7885 (1st) | 8350-8380 | BS-6 | BLW DS-4-4-660 | Ex-PRR 9000/9100/9200 series |

| 7886-7893 (1st) | 8381-8386 | BS-7 | BLW DS-4-4-750 | Ex-PRR 5500/5600 series |

| 7894-7899 (1st) | - | BS-8 | BLH S-8 | Ex-PRR 5994-5999 |

| 7900-7913 (1st) | 8387, 8388 | BS-7 | BLW DS-4-4-750 | Ex-PRR 5500/5600 series |

| 7914-8046 (1st) | 8263-8297 | BS-10m | BLW DS-4-4-1000 | Ex-PRR 5500/5900/9000/9100/9200 series |

| 8047, 8048 (1st) | - | BS-10 | BLW VO1000 | Ex-NYC 9300, 9301 |

| 8092-8112 (1st) | 8308-8316 | BS-12m | BLH S-12 | Ex-NYC 9308-9328 |

| 8113-8199 (1st) | 8317-8344 | BS-12m | BLH S-12 | Ex-PRR 8100/8700/8900 series |

| 8206-8210 | - | FS-10 | FM H10-44 | Ex-NYC 9106-9110 |

| 8211-8262 | - | FS-10 | FM H10-44 | Ex-PRR 5900/9000/9100/9200 series |

| 8300-8326 (1st) | - | FS-12 | FM H12-44 | Ex-NYC 9100 series |

| 8327-8342 (1st) | - | FS-12 | FM H12-44 | Ex-PRR 8700 series |

| 8400-8500 | - | ES-6m | EMD SW1 | Ex-NYC 500/600/700 series (some units sub-lettered for Chicago River & Indiana) |

| 8501-8599 | - | ES-6m | EMD SW1 | Ex-PRR 5900/9100/9200/9400 series |

| 8600-8627 | - | EMD SW8 | Ex-NYC 9600-9627 | |

| 8605 (2nd) | - | ES-8 | EMD SW8 | Ex-Merchants Despatch Transportation Company 15 |

| 8628-8646 | - | ES-9 | EMD SW900 | Ex-NYC 9628-9646; (some units sub-lettered for Cleveland Union Terminal) |

| 8647-8678 | - | ES-10m | EMD NW2 | Ex-PRR 5900/9100/9200 series |

| 8683-8699 | - | ES-10m | EMD NW2 | Ex-NYC 9500-9516; (built as New York, Ontario & Western 114, 116-131( |

| 8700-8704, 8750-8773 | - | ES-10m | EMD NW2 | Ex-NYC 8700-8704, 8750-8773 |

| 8795-8802 | - | ES-10m | EMD NW2 | Ex-Indiana Harbor Belt 8795-8802 |

| 8803-8810 | - | ES-10m | EMD NW2 | Ex-NYC 8803-8810 |

| 8836-8841 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-NYC 8836-8841; (some units sub-lettered for Chicago River & Indiana) |

| 8842-8850 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-Indiana Harbor Belt 8842-8850 |

| 8851-8855 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-NYC 8851-8855 |

| 8872-8874 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-Indiana Harbor Belt 8872-8874 |

| 8880-8903 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-NYC 8880-8903 |

| 8904-8906, 8908-8910 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-NYC (Peoria & Eastern) 8904-8906, 8908-8910 |

| 8907 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-Indiana Harbor Belt 8715 |

| 8911-9001 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW9 | Ex-NYC 8911-9001 |

| 9009-9034 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW1200 | Ex-PRR 7909-7934 |

| 9035-9041 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-PRR 9300 series |

| 9042-9044 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW9 | Ex-PRR 8542-8544 |

| 9045-9049 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-PRR 9300 series |

| 9050-9058 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW1200 | Ex-PRR 7900-7908 |

| 9059, 9060 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW9 | Ex-PRR 8859, 8860 |

| 9061-9094 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-PRR 9300 series |

| 9075 (2nd) | - | ES-12m | EMD NW2u | Ex-PC 8754 |

| 9095, 9096 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW9 | Ex-PRR 8869, 8870 |

| 9097, 9098 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW7 | Ex-PRR 8871, 8872 |

| 9099-9111 | - | ES-12m | EMD NW2u | Ex-PC 8600 series |

| 9113-9133 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW9 | Ex-PRR 8513-8533 |

| 9133 (2nd) | 9153 | ES-12m | EMD NW2u | Ex-PC 8704 |

| 9150-9152, 9154-9179 | - | ES-12m | EMD NW2u | Ex-PC 8600/9000 series |

| 9180-9199 | - | ES-12m | EMD SW1200 | Ex-NH 640-659 |

| (9216-9221) | - | - | EMD SW1500 | Built as Penn Central #9216-9221 but transferred to Indiana Harbor Belt. |

| 9223-9227 | - | ES15m | EMD SW1500 | Ex-IHB 9223-9227 |

| 9300-9347 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-NYC 800 series |

| 9348-9380 | - | AS6m | Alco S3 | Ex-NYC 800/900 series |

| 9382-9394 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-NYC 800 series |

| 9395-9402 | - | AS6m | Alco S3 | Ex-NYC 800/900 series |

| 9405, 9406, 9408 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-NYC 951, 952, 954 |

| 9411 | - | - | Alco HH660 | Ex-New Haven 0924 |

| 9412-9436, 9447-9449, 9457-9459 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-NH 0935-0977 |

| 9437-9446 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-PRR 9200 series |

| 9451, 9452, 9454-9456 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-PRR 9101, 9102, 5954-5956 |

| 9461-9470 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-PRR 5600 series |

| 9473-9485 | - | AS6m | Alco S3 | Ex-PRR 8700/8800 series |

| 9486-9499 | - | AS6m | Alco S1 | Ex-NH 0778-0995 |

| 9500-9583 | - | ES15m | EMD SW1500 | Purchased new. |

| 9600-9661 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-NYC 8500 series; 8505 (2nd) was ex-Delaware & Hudson 3024 |

| 9663-9703 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-NYC 8500/8600 series |

| 9704, 9705 | - | Alco S2 | Ex-NYC 851, 869 (2nd); ex-Delaware & Hudson 3031 and 3032 | |

| 9706-9727 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-NYC 8500 series |

| 9729, 9730 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-NYC 8598, 8623 |

| 9731, 9732 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-NYC 8541, 8548 |

| 9733-9765 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-NYC 8600 series |

| 9768-9777 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-PRR 8400 series |

| 9778-9787 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-PRR 5600/9200 series |

| 9788-9801, 9803 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-PRR 8800/8900 series |

| 9802, 9804-9814 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-PRR 5600/9100/9200 series |

| 9815, 9817 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-PRR 8487, 8887 |

| 9816, 9818-9821 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-PRR 5600/5900 series |

| 9822, 9823, 9830-9834 | - | AS10m | Alco S4 | Ex-PRR 8400 series |

| 9824-9828, 9836-9842 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-PRR 5600/5900 series |

| 9844-9849 | - | AS10a | Alco T6 | Ex-PRR 8424-8429 |

| 9850-9860 | - | AS10m | Alco S2 | Ex-NH 0600-0621 |

| 9999 | - | GS4 | GE 44 Ton | Ex-PRR 9353 |

Freight Cab Units

| Second Road Number | Original Road Number | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1300, 1319 | 1009, 1119 | AF-16 | Alco FA-1 | Ex-NYC #1009, #1119 (2nd) |

| 1302-1313 | 1102-1113 | AF-16 | Alco FA-2 | Ex-NYC #1102-1113 |

| 1330-1333 | - | AF-16 | Alco FA-1 | Ex-New Haven #0401, #0418, #0426, #0428 |

| 1345-1399 | 1045-1099 | AF-16 | Alco FA-2 | Ex-NYC #1045-1099 |

| 1400-1425 | - | EF-15 | EMD F3A | Ex-PRR #9524A-9689A |

| 1440-1538 | - | EF-15 | EMD F7A | Ex-PRR #9640A-9879A |

| 1617-1635 | - | EF-15 | EMD F3A | Ex-NYC #1617-1635 |

| 1636-1873 | - | EF-15a | EMD F7A | Ex-NYC #1636-1873 |

| 1878, 1879 | 721, 754 | EF-15a | EMD F7A | Ex-Rio Grande #5721, #5754 |

| 1900-1906 | - | EF-15a | EMD F7A | Ex-PRR #9656A-9661A, #9666A; 1905 only unit painted in Penn Central colors. |

| 3323-3372 | - | AF-16 | Alco FB-2 | Ex-NYC |

| 3368 (2nd) | - | AF-16 | Alco FB-1 | Ex-NYC #3368 (2nd) |

| 3390-3392 | - | AF-16 | Alco FB-1 | Ex-New Haven #0456, #0458, #0462 |

| 3393-3397 | - | AF-16 | Alco FB-2 | Ex-New Haven #0465-0469 |

| 3423-3442 | - | EF-15a | EMD F7B | Ex-NYC #2423-2442 |

| 3443-3474 | - | EF-15 | EMD F3B | Ex-NYC #2443-2474 |

| 3478, 3479 | 712, 733 | EF-15a | EMD F7B | Ex-Rio Grande #5712, #5733 |

| 3500-3507 | - | EF-15 | EMD F3B | Ex-PRR #9524B-9554B |

| 3508-3563 | - | EF-15a | EMD F7B | Ex-PRR #9547B-9878B |

First Generation Four-Axle Road Units

| Original Road Number(s) | Second Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3800-3829 | - | EF17 | EMD GP9B | Ex-PRR 7175B-7204B |

| 3830-3839 | - | EF17 | EMD GP9B | Ex-PRR 7230B-7239B |

| 5100-5112 | - | FRS-7a | FM H16-44 | Ex-NYC 7000-7012 |

| 5150-5159 | - | FRS-7a | FM H16-44 | Ex-PRR 8807-8816 |

| 5160-5174 | - | FRS-7a | FM H16-44 | Ex-NH 1600-1614 |

| 5207, 5210, 5212, 5215, 5221, 5229 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS2 | Ex-NYC 8207, 8210, 8212, 8215, 8221, 8229 |

| 5203, 5205, 5223-5352 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-NYC 8203, 8205, 8223-8352 |

| 5400, 5401 (1st) | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8600, 8601 |

| 5401 (2nd) | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS2 | Ex-Lehigh Valley 212 (1st) |

| 5402-5405, 5409, 5411 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8602-8605, 8909, 8592 |

| 5413-5416 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8903, 8904, 8435, 8436 |

| 5418-5436 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8818-8836 |

| 5437-5442 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8437-8442 |

| 5443-5451 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8593-8599, 8590, 8591 |

| 5452-5470 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8452-8470 |

| 5461 (2nd) | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS2 | Ex-Lehigh Valley 210 (1st) |

| 5471-5484 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-New Haven 500 series |

| 5500-5530 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-NYC 8247-8291 |

| 5531-5536, 5544 (2nd) | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-New Haven 500 series |

| 5537-5555 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8800 series |

| 5554, 5559, 5561, 5564, 5566, 5570 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-New Haven 500 series |

| 5557-5565 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8900 series |

| 5567-5584 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-PRR 8400 series |

| 5585-5598 | - | ARS-16 | Alco RS3 | Ex-New Haven 500 series |

| 5600-5625 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-NYC #5600-5625; 5612-5625 sublettered for Peoria & Eastern |

| 5626-5712 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-NYC 5626-5712 |

| 5719 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-Pittsburgh & Lake Erie 5719 |

| 5738-5812 | - | ES15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-NYC 5738-5812 |

| 5818-5827 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-NYC 5818-5827, (built as Chesapeake & Ohio #5720-5729) |

| 5840-5844 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-PRR 8840-8844 |

| 5845-5892 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-PRR 8500-series |

| 5895-5899 | - | ERS15 | EMD GP7 | Ex-PRR 8805, 8806, 8797-8799 |

| 5900-5927 | - | ERS15s | EMD GP7 | Ex-NYC 5700, 5800-series |

| 5950-5959 | - | ERS15s | EMD GP7 | Ex-PRR 8500-series |

| 6700-6708 (1st) | 6799 (ex-6708) | FS24m | FM H24-66 | Ex-PRR 8700-8707, 8699 |

| 6800-6805 | - | ARS16a | Alco RSD5 | Ex-PRR 8446-8451 |

| 6806-6810 | - | APS24ms | Alco RSD7 | Ex-PRR 8606-8610 |

| 6811-6816 | - | ARS24 | Alco RSD15 | Ex-PRR 8611-8616 |

| 6855-6879 | - | ARS18a | Alco RSD12 | Ex-PRR 8655-8679 |

| 6900-6924 | - | ERS17a | EMD SD9 | Ex-PRR 7600-7624 |

| 6950, 6951 (1st) | 6998, 6999 | ERS15ax | EMD SD7 | Ex-PRR 8588, 8589 |

| 6966-6974 | - | BRS16m | BLH AS616 | Ex-PRR 8966-8974 |

| 6975, 6976 | - | BRS16m | BLH AS616 | Ex-PRR 8111, 8112 |

| 7000-7269 | - | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-PRR 7000-7269 |

| 7300-7303 | - | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-NYC (Cleveland Union Terminal) 5900-5903 |

| 7304-7327, 7346-7475 | - | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-NYC 5904-6075 |

| 7348, 7369, 7380, 7420, 7452, 7519 | - | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-NYC 5900/6000 series |

| 7500-7518 | 7329-7344, 7347 | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-NYC 5900-series |

| 7530-7559 | 7270-7298 | ERS17 | EMD GP9 | Ex-NH 1200-1229 |

| 7600-7608 | - | ARS18 | Alco RS11 | Ex-NYC 8000-8008 |

| 7617-7654 | - | ARS18 | Alco RS11 | Ex-PRR 8617-8654 |

| 7660-7674 | - | ARS18 | Alco RS11 | Ex-NH 1400-1414 |

| 8050-8053 | 8300-8302 | BRS10sx | BLW DRS-4-4-1000 | Ex-PRR 9276, 5591-5593 |

| 8062, 8063 | 8398, 8399 | LERS12as | Lima-Hamilton 1,200 Horsepower Road-Switcher | Ex-NYC 6210, 6211 (EMD-repowered) |

| 8067-8083 | - | BRS12m | BLW RS12 | Ex-NYC 6220-6236 |

| 8084-8091 | 8303-8306 | BRS12m | BLW RS12 | Ex-PRR 8975, 8110, 8776, 8107-09, 05, 06 |

| 9900-9913 | - | ARS10/a/sx | Alco RS1 | Ex-NYC 8100-8113 |

| 9914-9940 | - | ARS10/a/sx | Alco RS1 | Ex-PRR 5600 / 5900 / 8400 / 8800 series |

| 9941-9946 | - | ARS10/a/sx | Alco RS1 | Ex-NH 0662-0665, 0667, 0671 |

| 9948, 9949 | 9949A, 9949B | - | AEH-12/Slug | Ex-PC 6803 (2nd), 6811 |

| 9950-9984 | - | AERS12 | Alco RS3m (EMD-repowered) | Ex-PC 5200 / 5300 / 5400 / 5500-series |

Contemporary Four-Axle Road Units

| Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-2014 | ERS20 | EMD GP38 | Ex-PRSL 2010-2014 |

| 2021-2044 | AF20 | Alco RS32 | Ex-NYC 8021-8044 |

| 2050-2059 | AF30 | Alco C430 | Ex-NYC 2050-2059 |

| 2100-2112 | EF20 | EMD GP20 | Ex-NYC 6100-6105, 6107, 6108, 6110-6114 |

| 2188-2197 | EF22 | EMD GP30 | Ex-NYC 6115-6124 |

| 2198-2249 | EF22 | EMD GP30 | Ex-PRR 2250, 2251, 2200-2249 |

| 2250-2308 | EF25 | EMD GP35 | Ex-PRR 2309, 2310, 2252-2308 |

| 2309-2351 | EF25 | EMD GP35 | Ex-PRR 2369, 2370, 2311-2351 |

| 2353-2368 | EF25 | EMD GP35 | Ex-PRR 2353-2368 |

| 2369-2398 | EF25 | EMD GP35 | Ex-NYC 6125-6154 |

| 2399 | EF25 | EMD GP35 | Ex-NYC 6155, exx-demonstrator 1964, nee-demonstrator 5661 |

| 2400-2414 | AF24 | Alco RS27 | Ex-PRR 2400-2414 |

| 2415 | AF24 | Alco C424 | Ex-PRR 2415 |

| 2416-2446 | AF25 | Alco C425 | Ex-PRR 2416-2446 |

| 2450-2459 | AF25 | Alco C425 | Ex-New Haven 2550-2559 |

| 2500-2569 | GF25 | GE U25B | Ex-NYC 2500-2569 |

| 2600-2658 | GF25 | GE U25B | Ex-PRR 2500-2548, 2649-2658 |

| 2660-2685 | GF25 | GE U25B | Ex-New Haven 2500-2525 |

| 2700-2776 | GF22 | GE U23B | Purchased new. |

| 2822, 2823 | GF28 | GE U28B | Ex-NYC 2822, 2823 |

| 2830-2857 | GF30 | GE U30B | Ex-NYC 2830-2857 |

| 2858, 2859 | GF33 | GE U33B | Ex-NYC 2858, 2859 |

| 2860-2889 | GF30 | GE U30B | Ex-NYC 2860-2889 |

| 2890-2970 | GF33 | GE U33B | Purchased new. |

| 3000-3104 | EF30 | EMD GP40 | Ex-NYC 3000-3104 |

| 3105-3259 | EF30 | EMD GP40 | Purchased new. |

| 3260-3274 | EF30 | EMD GP40 | Ex-demonstrators 11-20 and 22-26 |

| 7675-7939 (2nd) | EF20 | EMD GP38 | Purchased new. |

| 7940-8162 | EF20 | EMD GP38 | Purchased new. |

Contemporary Six-Axle Road Units

| Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6000-6039 | EF25a | EMD SD35 | Ex-PRR 6000-6039 |

| 6040-6104 | EF30a | EMD SD40 | Ex-PRR 6040-6104 |

| 6105-6234 | EF36 | EMD SD45 | Ex-PRR 6105-6234 |

| 6235-6239 | EF36 | EMD SD45 | Purchased new. |

| 6240-6284 | EF30a | EMD SD40 | Purchased new. |

| 6300-6314 | AF27 | Alco C628 | Ex-PRR 6300-6314 |

| 6315-6329 | AF30a | Alco C630 | Ex-PRR 6315-6329 |

| 6330-6344 | AF36 | Alco C636 | Purchased new. |

| 6500-6519 | GF25a | GE U25C | Ex-PRR 6500-6519 |

| 6520-6534 | GP28a | GE U28C | Ex-PRR 6520-6534 |

| 6535-6539 | GF30a | GE U30C | Ex-PRR 6535-6539 |

| 6540-6559 | GF33a | GE U33C | Purchased new. |

| 6560-6563 | GF33a | GE U33C | Purchased new. |

| 6700-6718 (2nd) | GRS22 | GE U23C | Purchased new. |

| 6925-6959 | ERS20a | EMD SD38 | Purchased new. |

Passenger Cab Units

| Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4000-4035 | EP20 | EMD E7A | Ex-NYC 4000-4035 (4003 and 4020 rebuilt as E8Am) |

| 4036-4095 | EP22 | EMD E8A | Ex-NYC 4036-4095 |

| 4100-4113 | EP20 | EMD E7B | Ex-NYC 4100-4113 |

| 4114-4127 | EP20 | EMD E7B | Ex-PRR 5900B, 5840B-5864B (Evens) |

| 4150-4163 | EP20 | EMD F7B | Ex-PRR 9832B-9858B (Evens) |

| 4200-4245 | EP20 | EMD E7A | Ex-PRR 5900, 5901, 5840A-5883A |

| 4246-4319 | EP22 | EMD E8A | Ex-PRR 5700/5800 Series |

| 4320-4328 | EP22 | EMD E8A | Ex-PC/NYC 4000 Series |

| 4332-4371 | EFP15 | EMD FP7 | Ex-PRR 9832A-9871A |

| 5000-5059 | EP17e/EP18e | EMD FL9 | Ex-New Haven 2000-2059 |

Electrics

| Road Number(s) | PC Class | Builder/Model | Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4400-4457 | E44 | GE E44 | Ex-PRR 4400-4457 |

| 4458-4465 | E44a | GE E44a | Ex-PRR 4458-4465 |

| 4600-4610 | E33 | GE E33 | Ex-NH 300-310, nee-Virginian Railway |

| 4622 | Alco/GE P-2a | Ex-NYC 222 | |

| 4623-4642 | P-2b | Alco/GE P-2b | Ex-NYC 223-242 |

| 4655 | T-1a | Alco/GE T-1a | Ex-NYC 255 |

| 4662 | T-2a | Alco/GE T-2a | Ex-NYC 262 |

| 4663, 4666, 4667, 4669, 4671 | T-2b | GE T-2b | Ex-NYC 263, 266, 267, 269, 271 |

| 4673-4676, 4678-4680 | T-3a | Alco/GE T-3a | Ex-NYC 273-276, 278-280 |

| 4702-4733 | S-2 | Alco/GE S-2 | Ex-NYC 102-133 |

| 4751-4757 | B-1 | PRR/Allis-Chalmers B-1 | Ex-PRR 3912, 3913, 5685-5693 |

| 4780, 4781 | DD-1 | PRR/Westinghouse DD-1 | Ex-PRR 3936, 3937 |

| 4790 | L-6 | PRR/GE L-6 | Ex-PRR 5939 |

| 4791 | L-6a | Lima L-6a | Ex-PRR 5940 |

| 4800 | GG-1 | BLW/GE GG-1 | Ex-PRR 4800 (original GG-1, "Ole Rivets") |

| 4801-4814 | GG-1 | GE GG-1 | Ex-PRR 4801-4814 |

| 4815, 4816 | GG-1 | BLW/PRR/Westinghouse GG-1 | Ex-PRR 4815, 4816 |

| 4818-4938 | GG-1 | GE/Westinghouse GG-1 | Ex-PRR 4818-4938 |

| 4970-4977 | E40 | GE E40 | Ex-NH 371-377, 379 |

Penn Central RS-3's (#5349, #5441, and #5340) head south on the Belt Line behind Central Terminal in Buffalo, New York on August 12, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.

Penn Central RS-3's (#5349, #5441, and #5340) head south on the Belt Line behind Central Terminal in Buffalo, New York on August 12, 1973. Doug Kroll photo.Conrail

In the end, the railroad's failure eventually improved the industry for the better; Amtrak launched on May 1, 1971, largely relieving railroads of their money losing passenger operations, while the creation of Conrail on April 1, 1976 pieced together the bankrupt shells of several Northeastern lines, including Penn Central.

It took several years but Conrail earned its first profit in 1981, netting $39 million that year. There were several factors which led to this turnaround but one of the most important was the Staggers Rail Act of 1980.

Perhaps Morgan best summed it best up best, all the while articulating the industry's problems: "The point is why in a thriving U.S. economy the biggest railroads in the nation find it necessary to make public such a drastic panacea.

The answer, all but obscured by inept railroad explanation and a nervous competition, is that railroading has been manacled by archaic regulation drawn up in an era when the objective was to see to it that certain roads did not harm the economy while they were clouting one another over the head in the excesses of a vanished day of laissez-faire.

Thus railroading has been unable to stop the advance of water, road and air competition that has always been backed to the hilt by public money and frequently merchandised by Government. That is the point."

Incredibly, this was said in 1958, a decade before Penn Central's creation and more than two decades before deregulation.

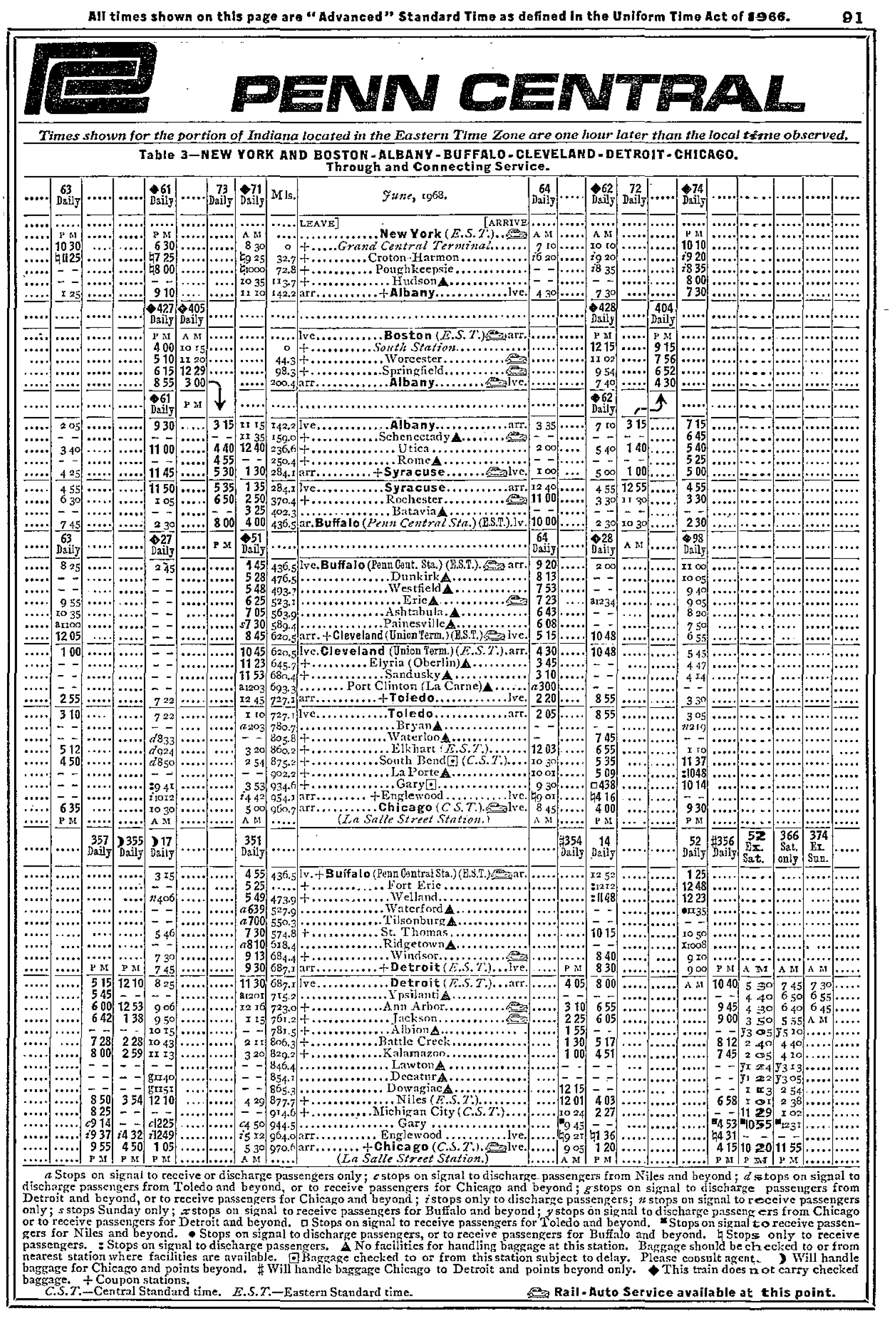

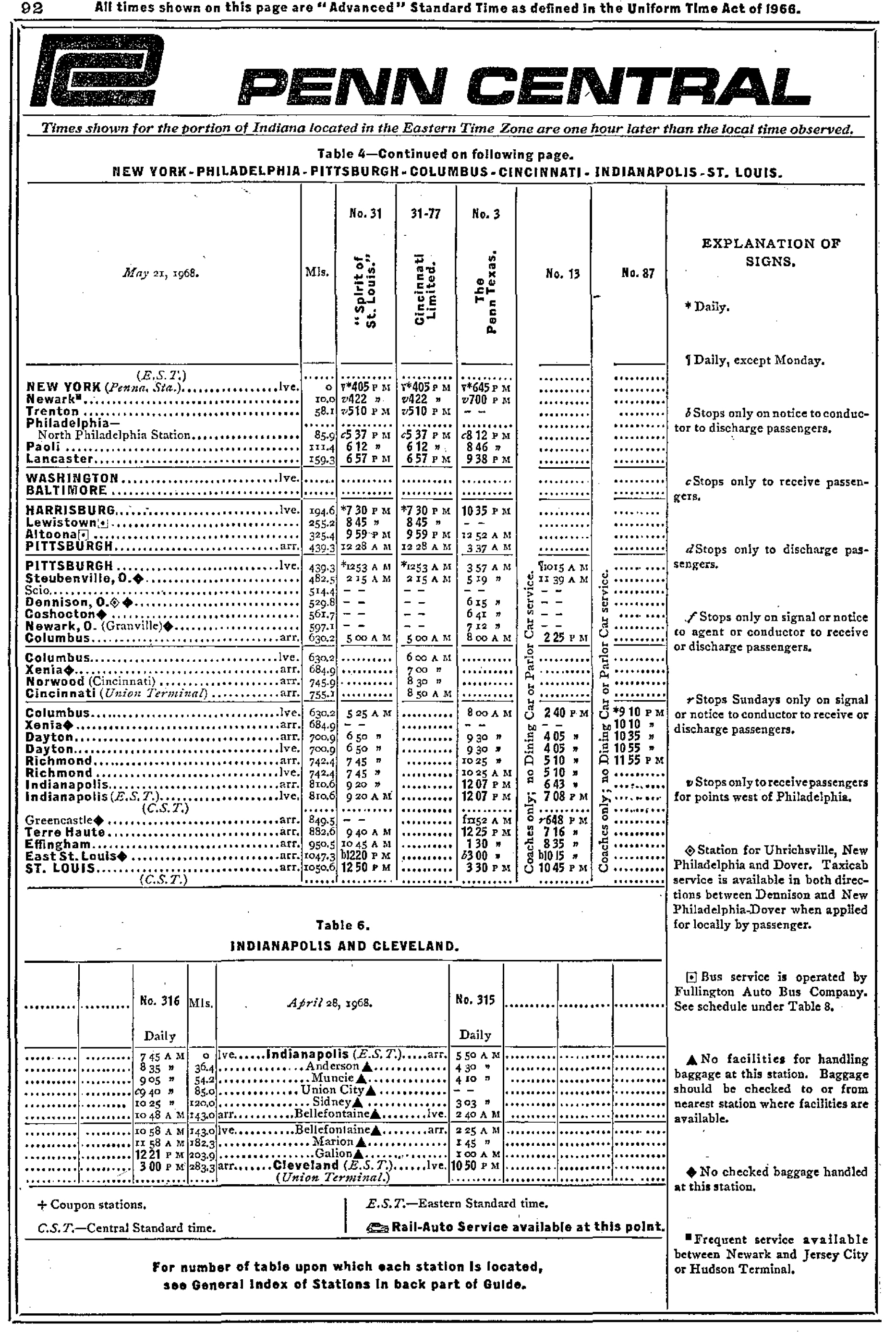

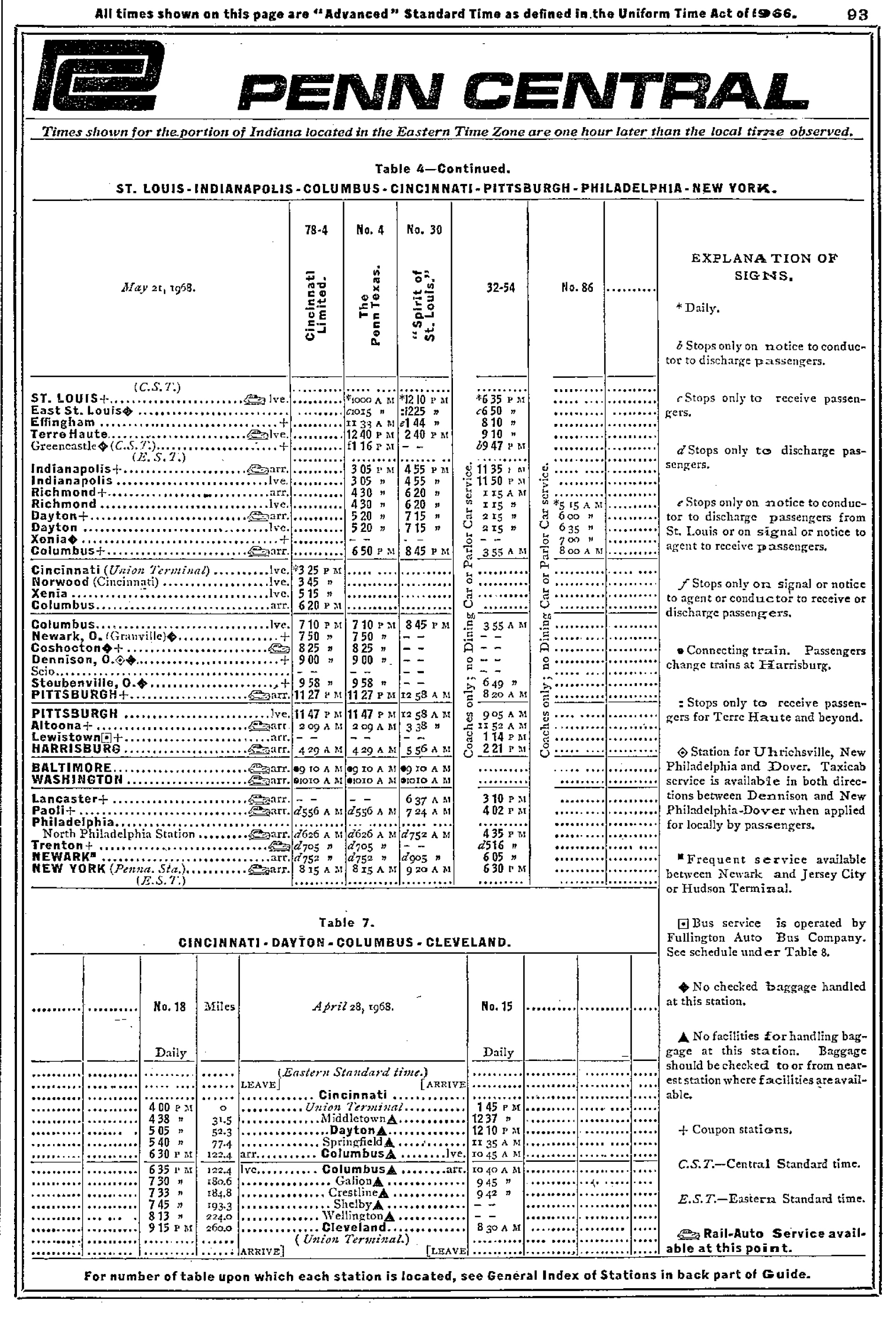

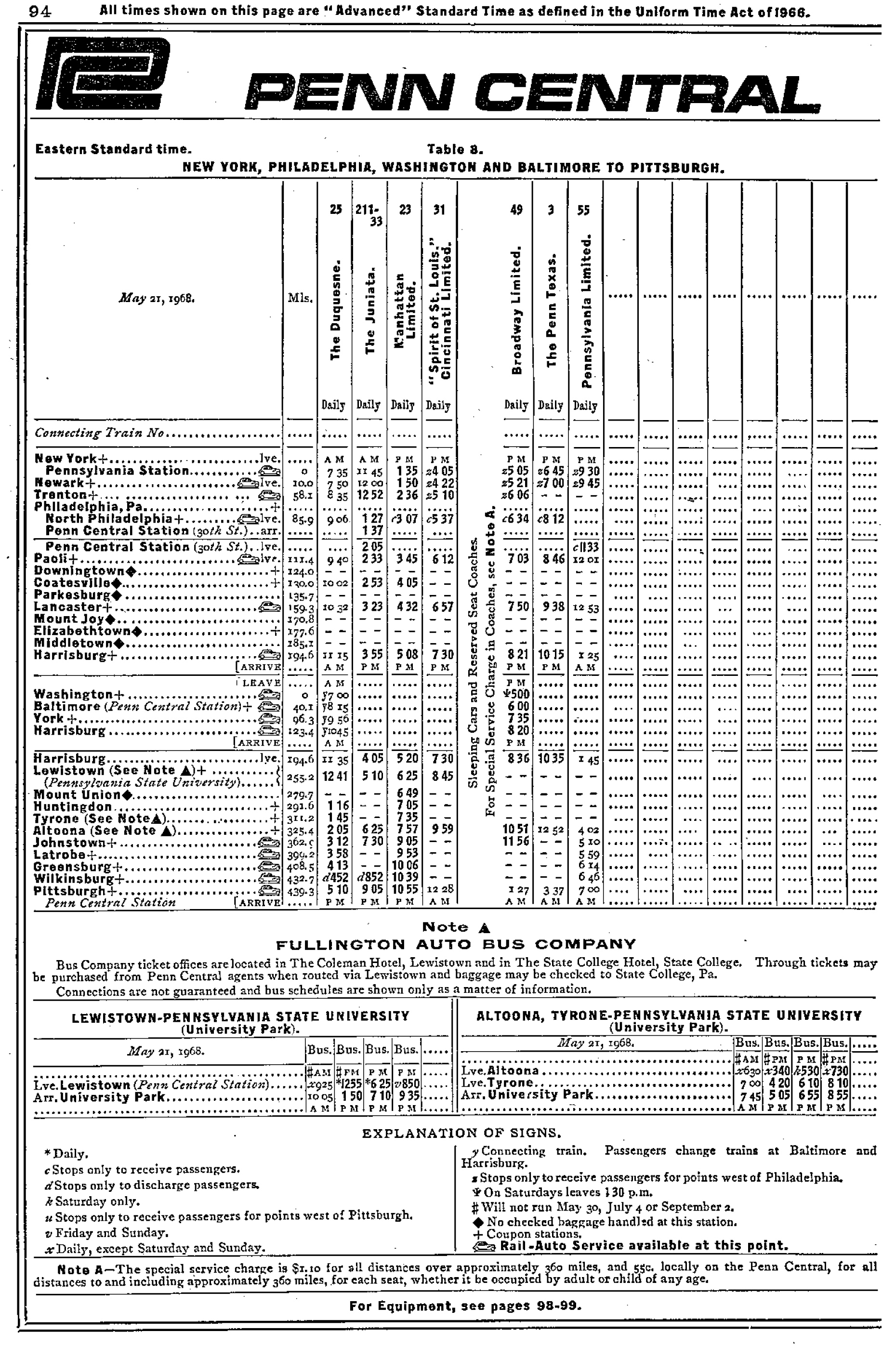

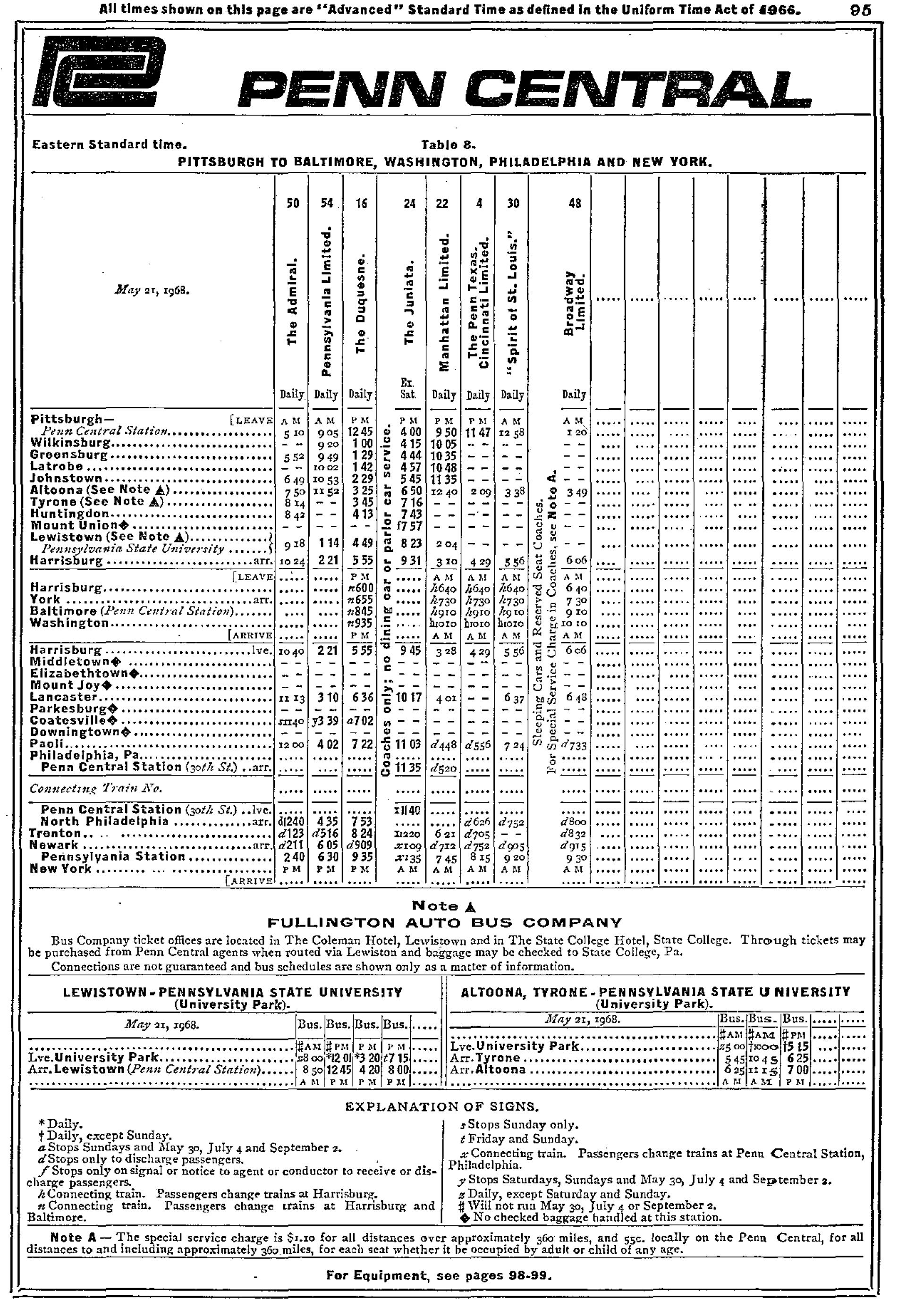

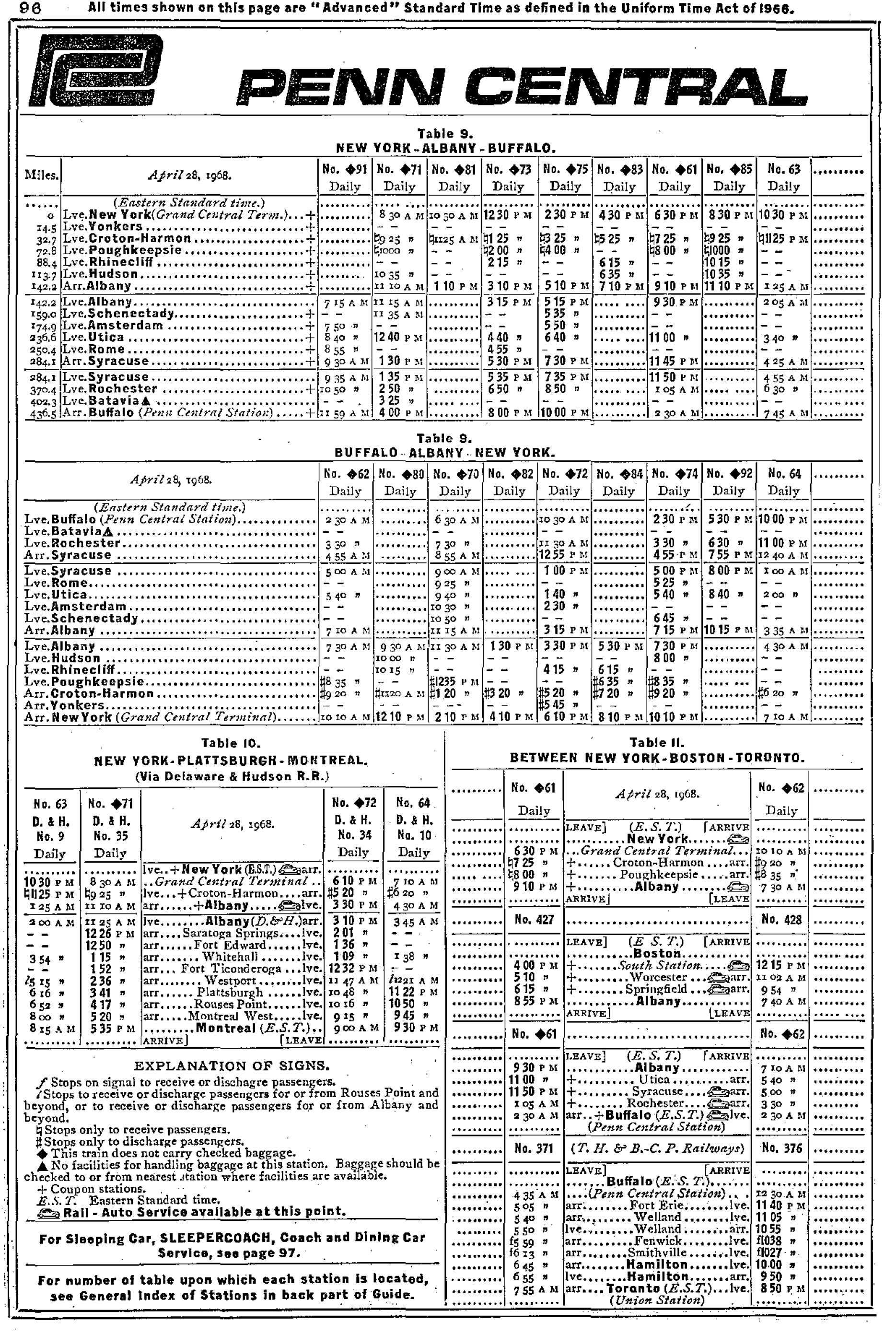

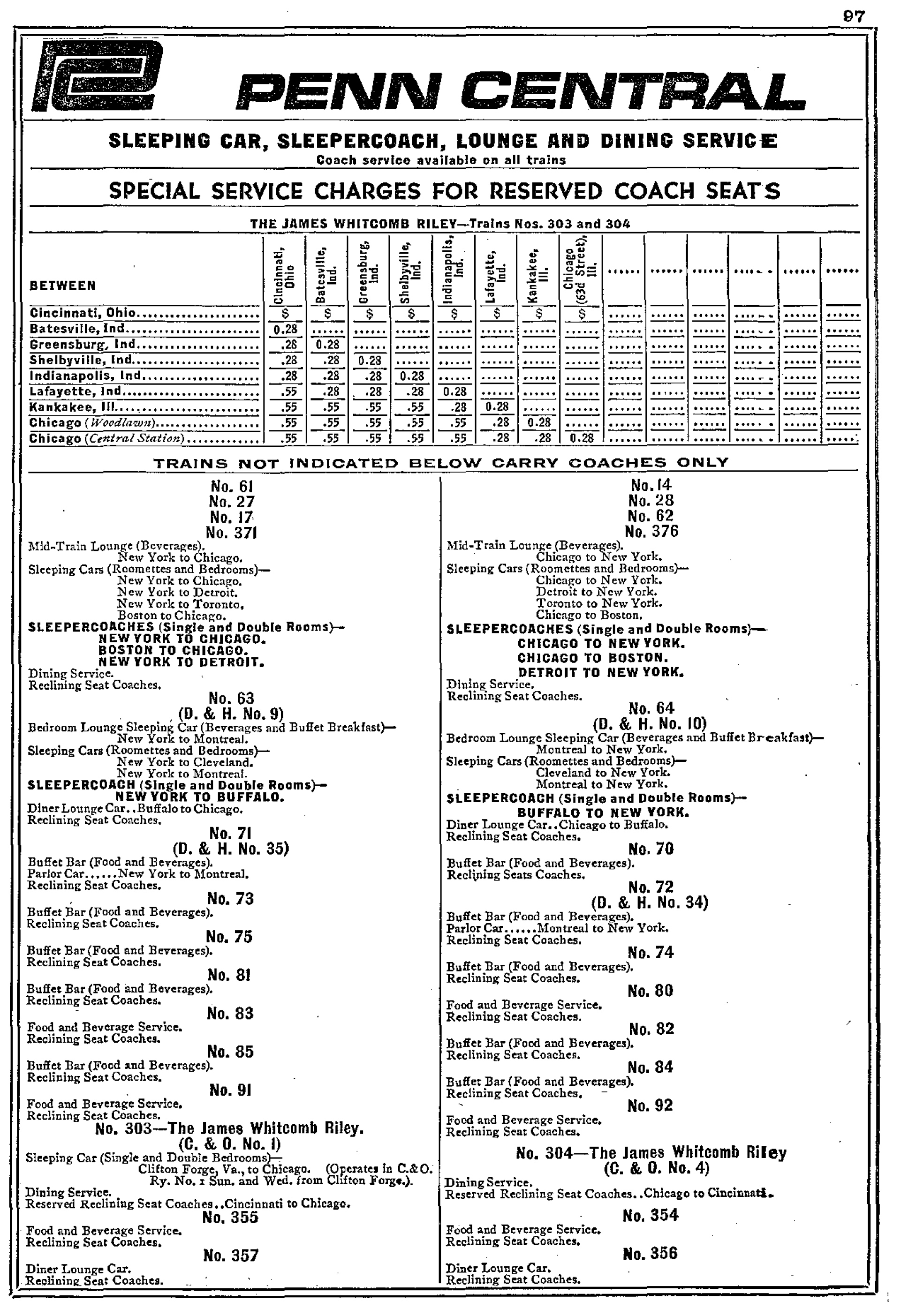

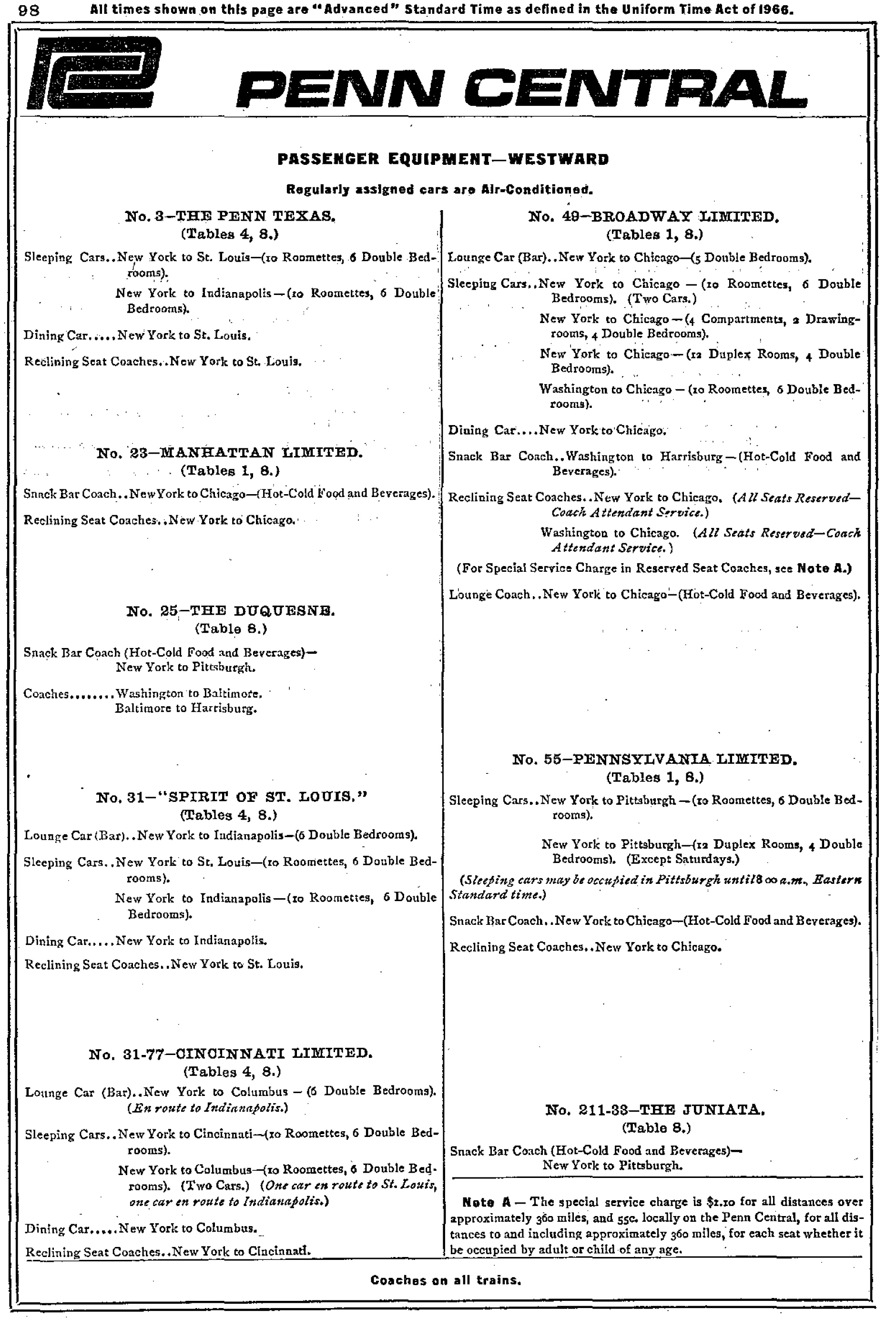

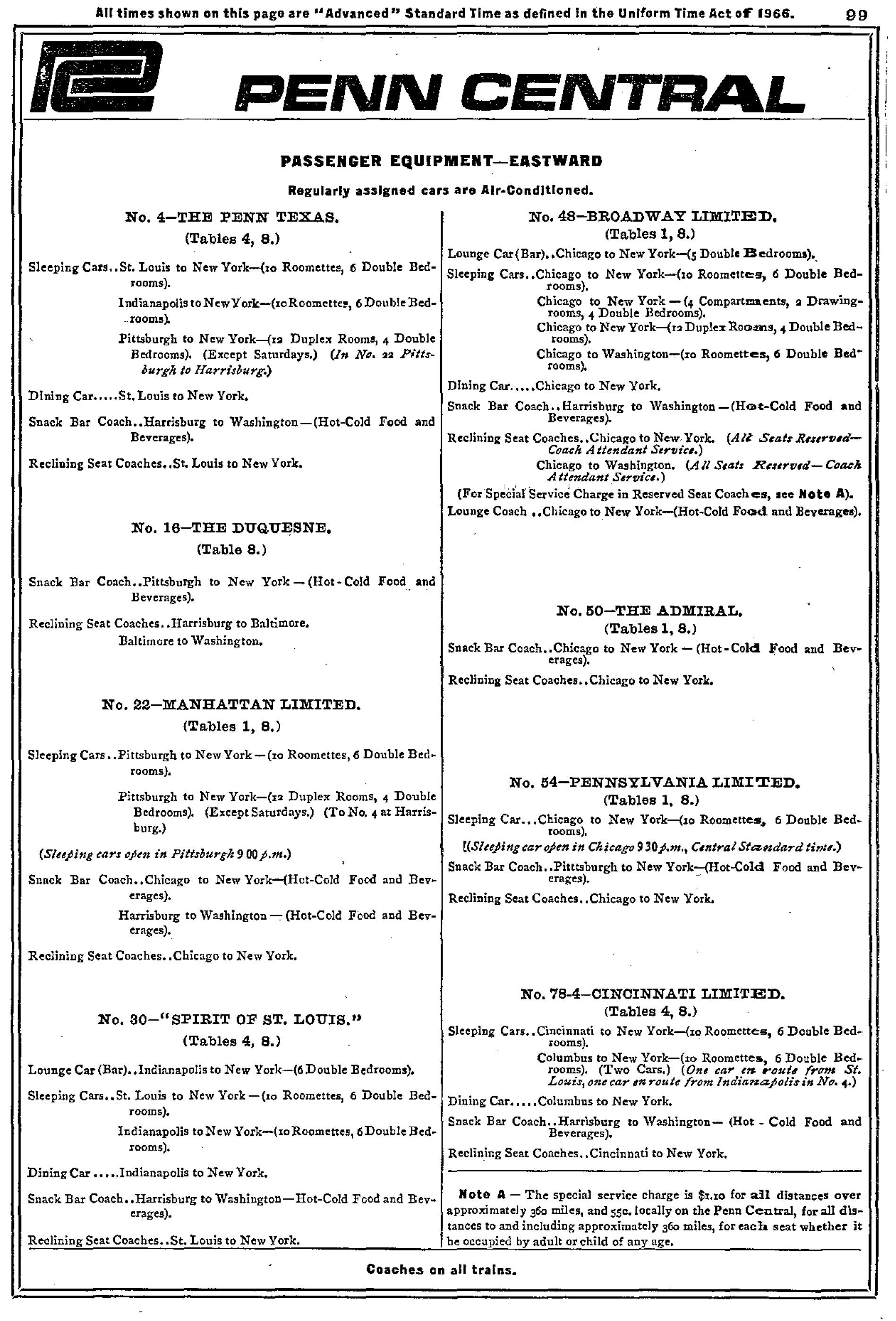

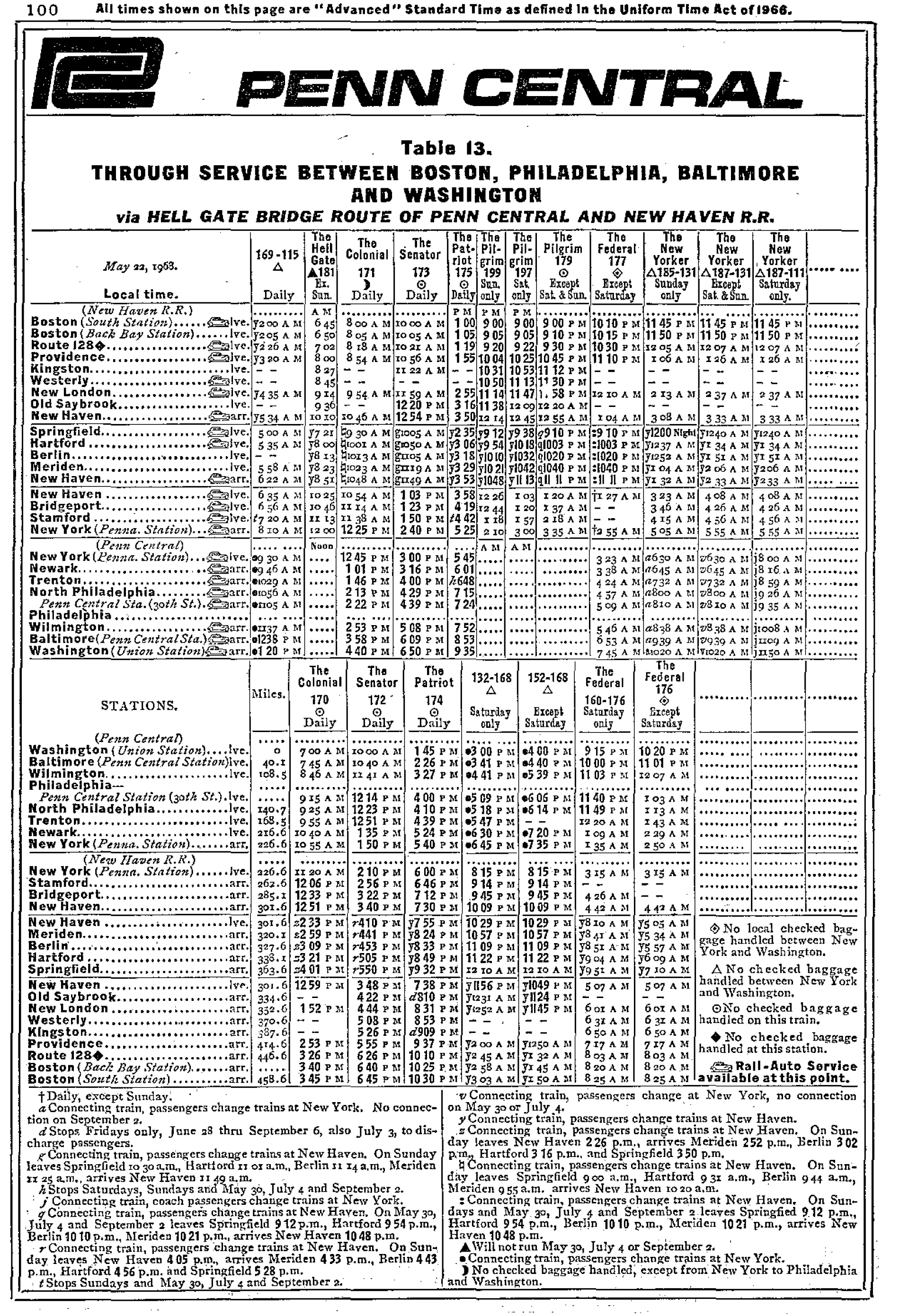

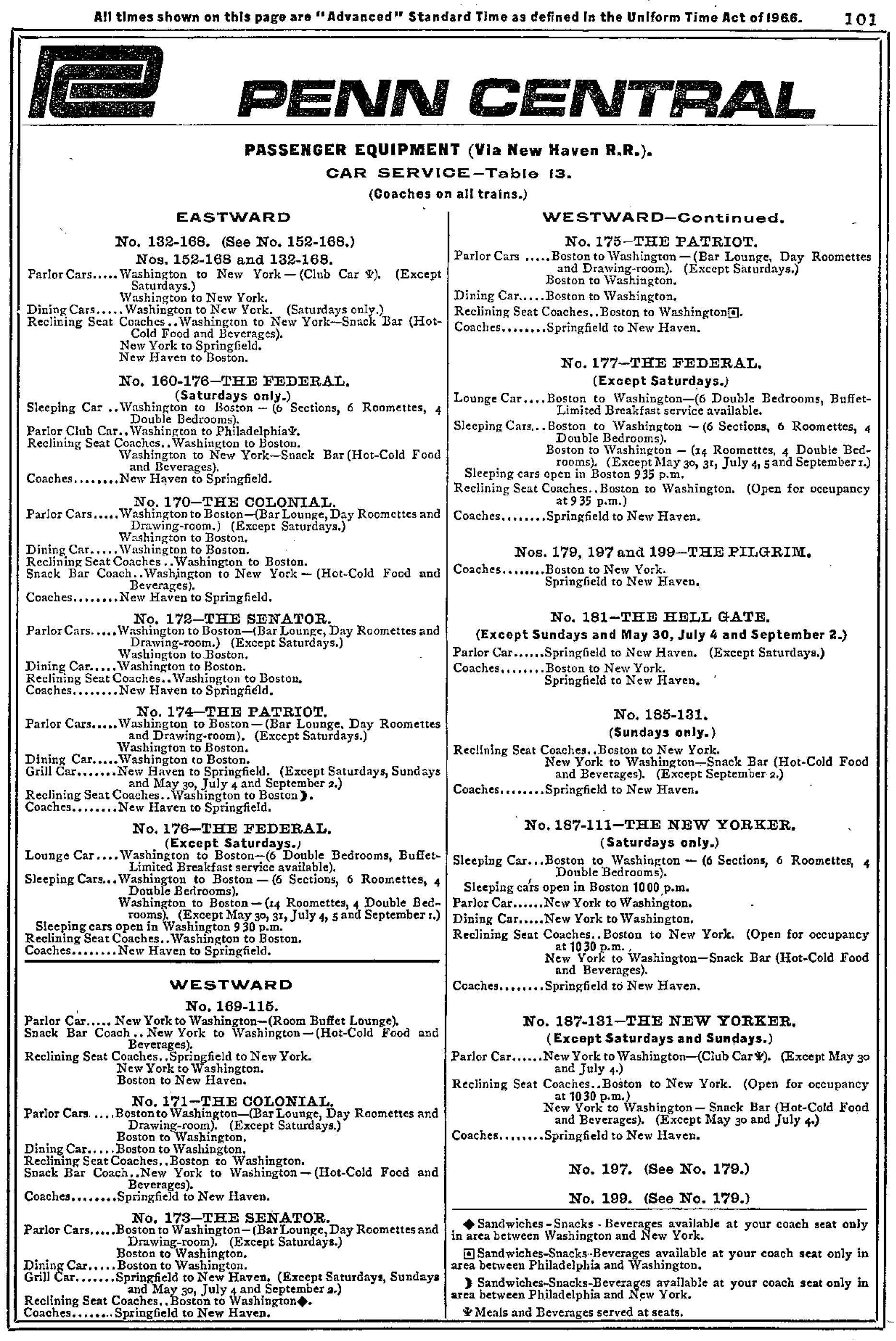

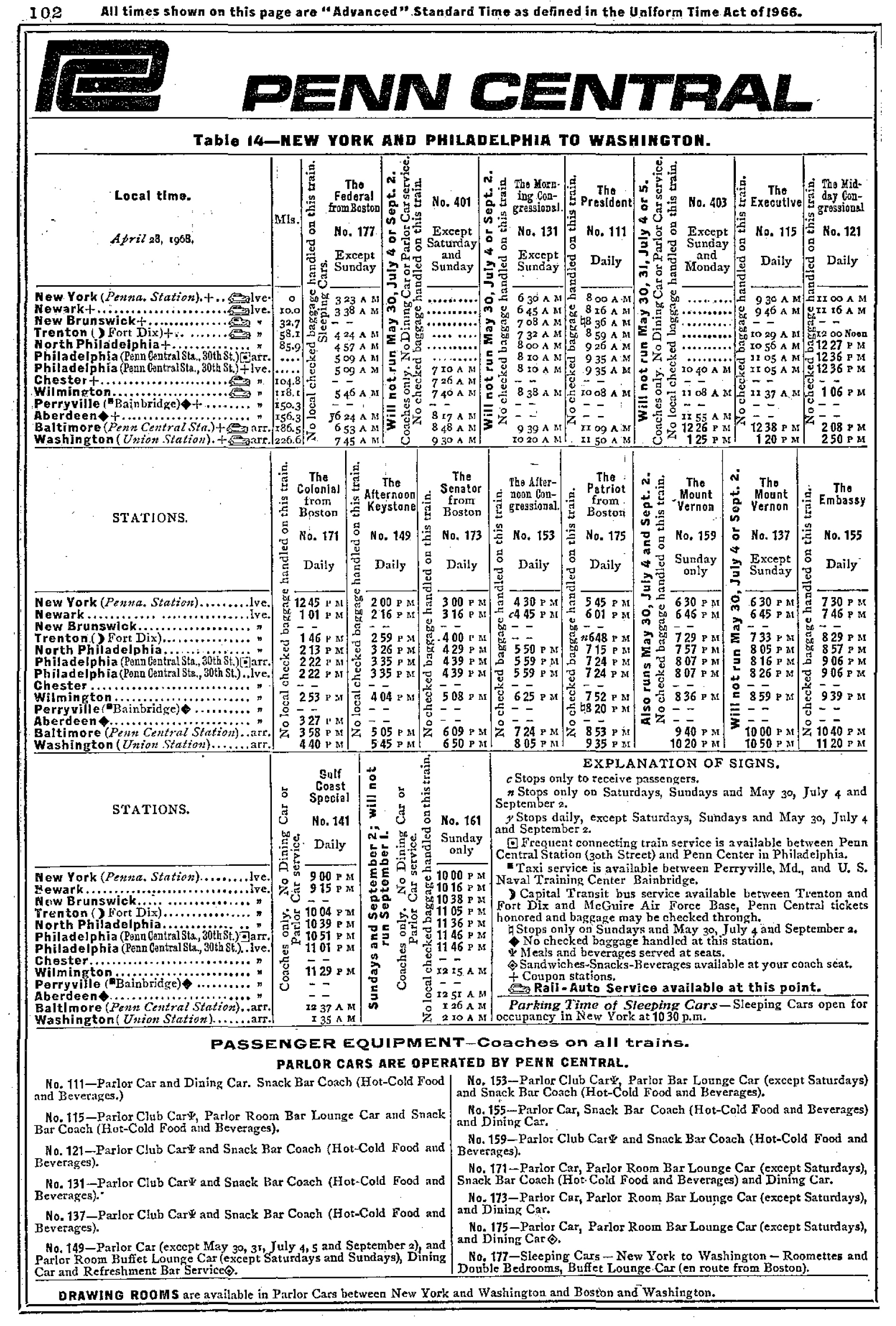

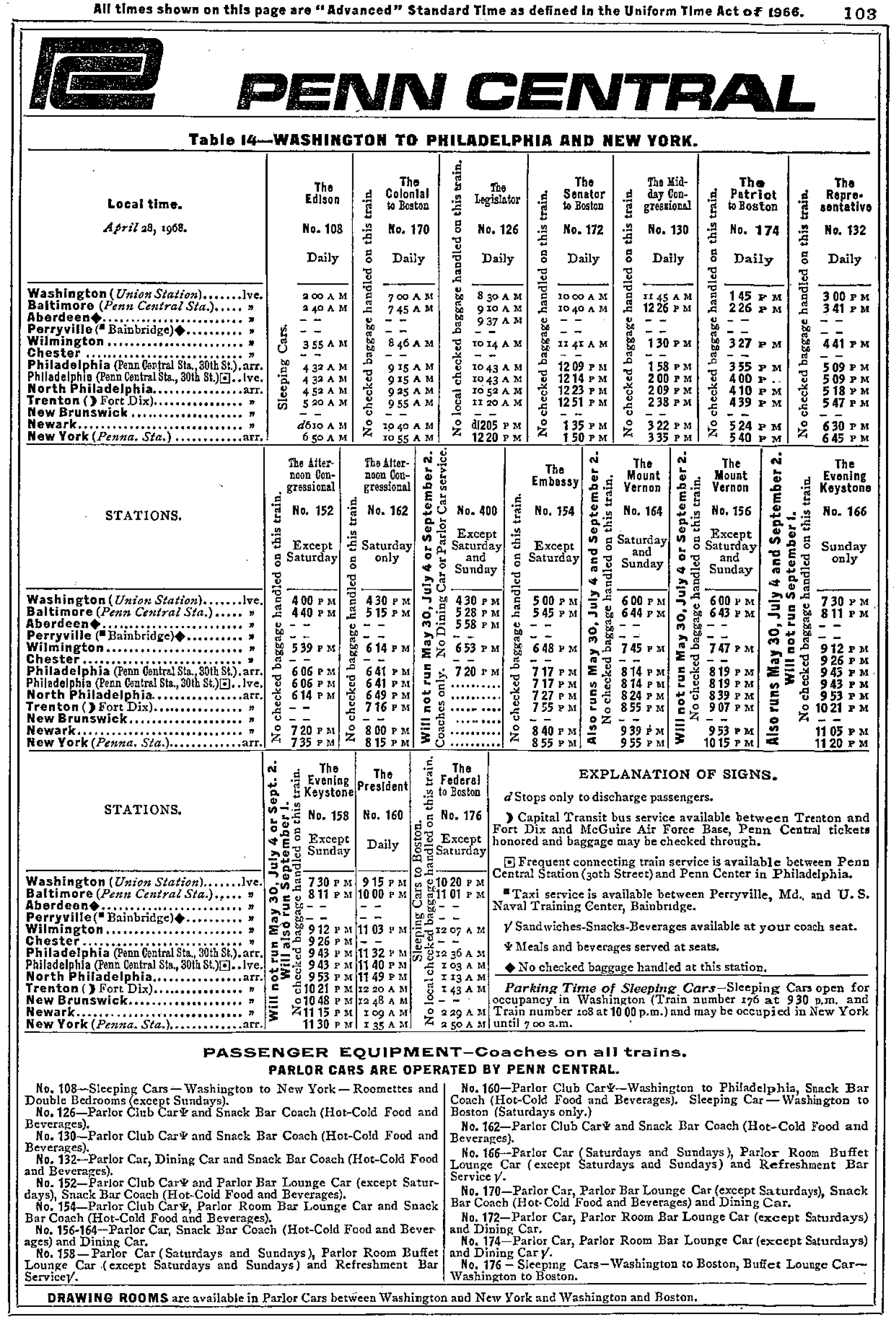

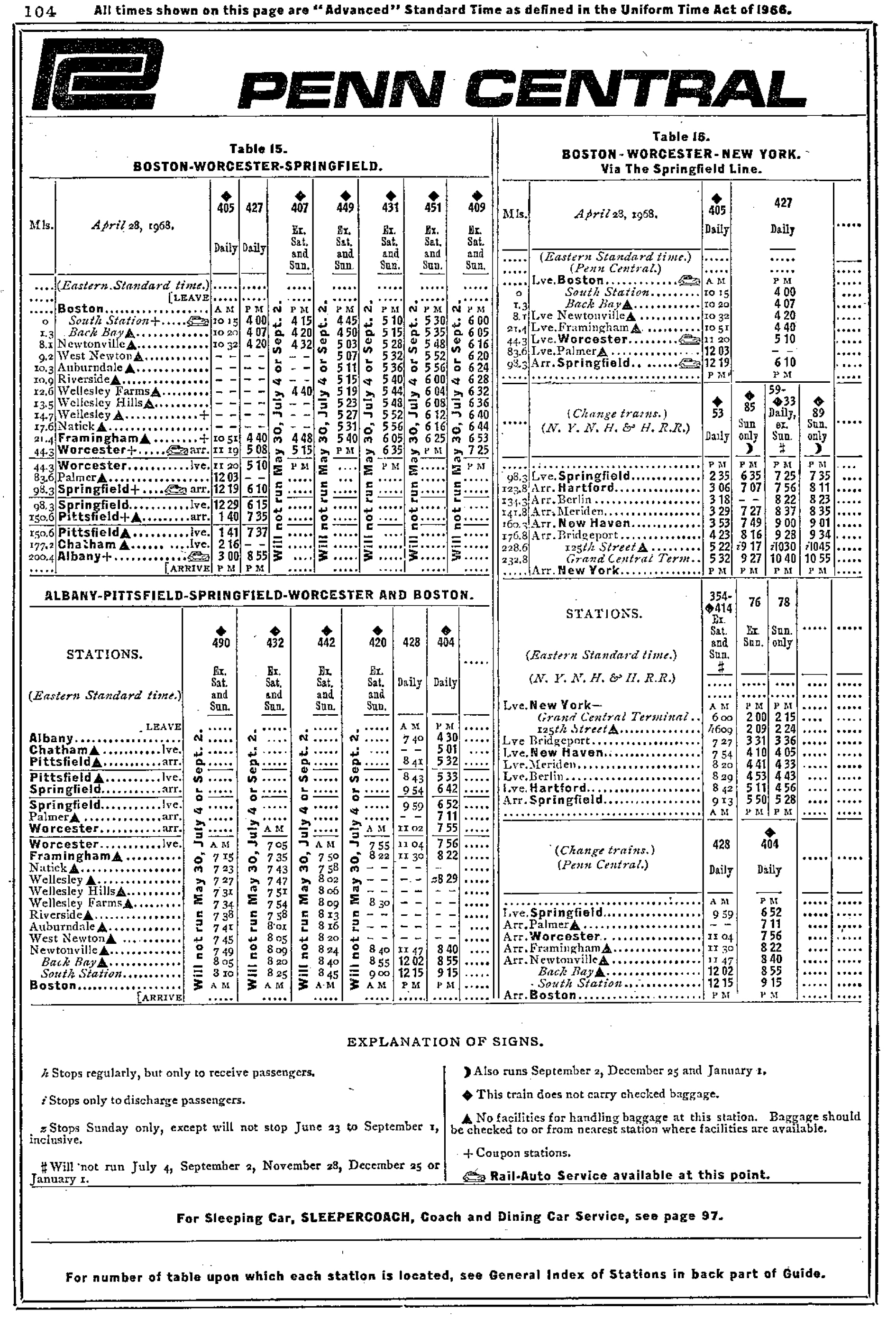

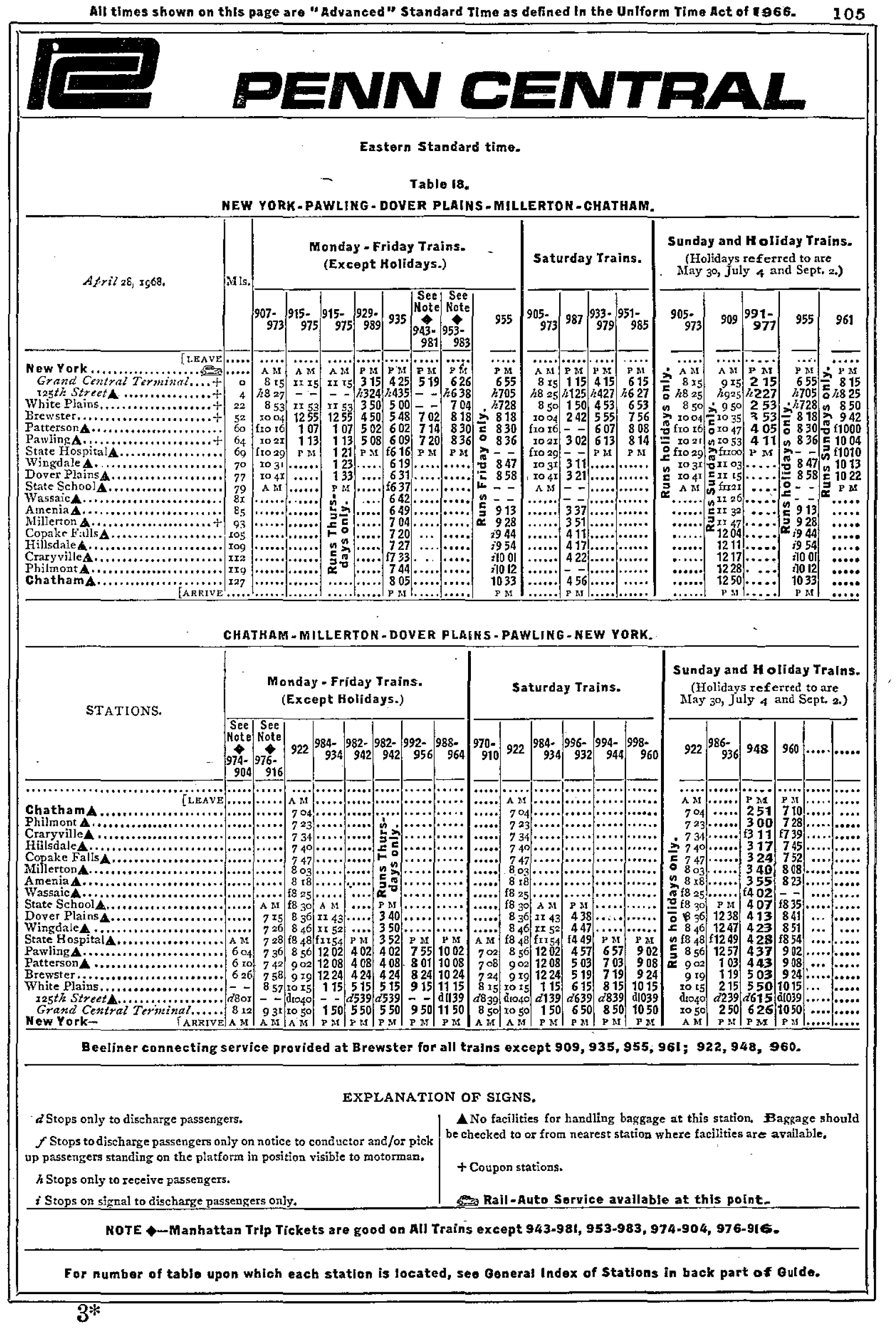

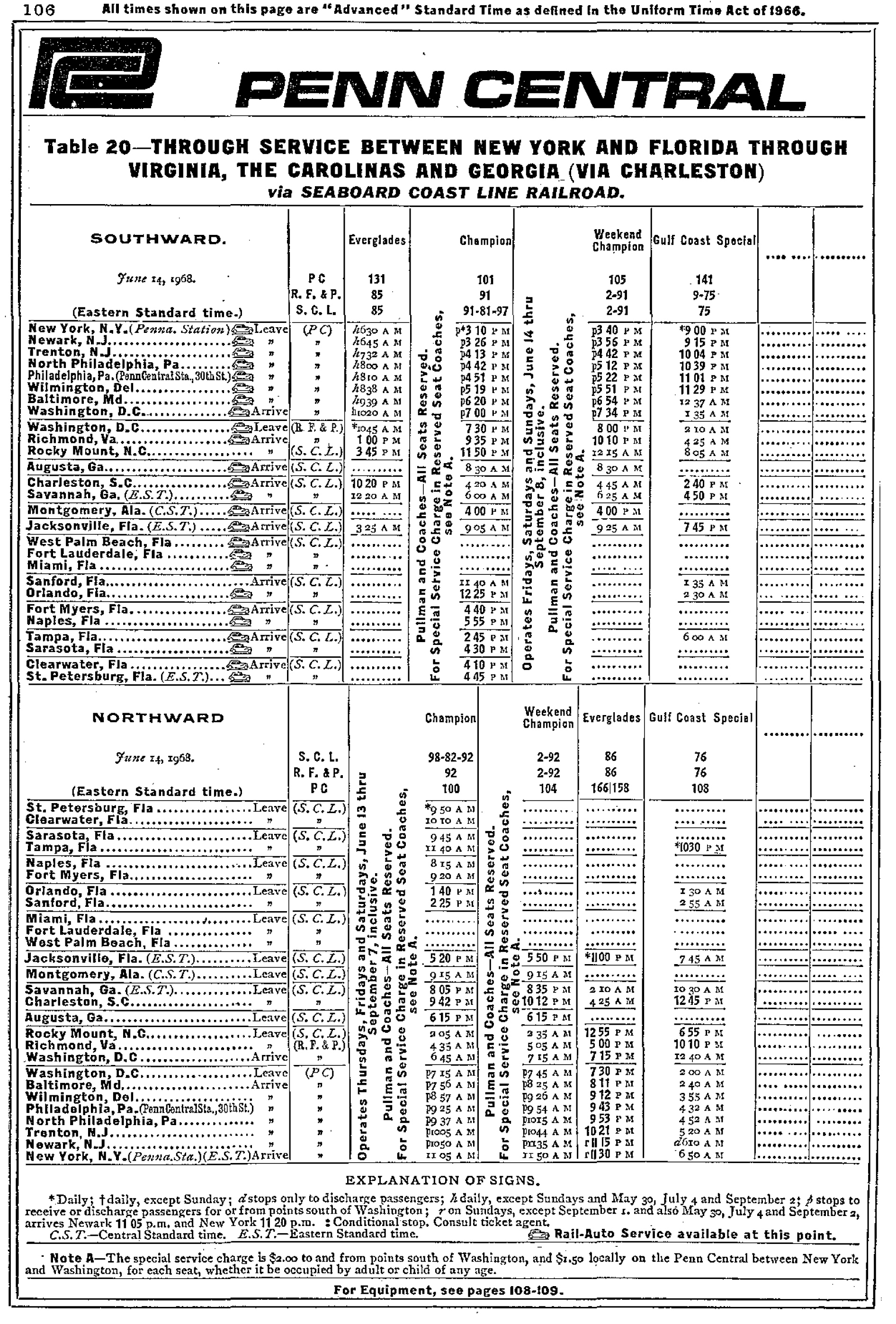

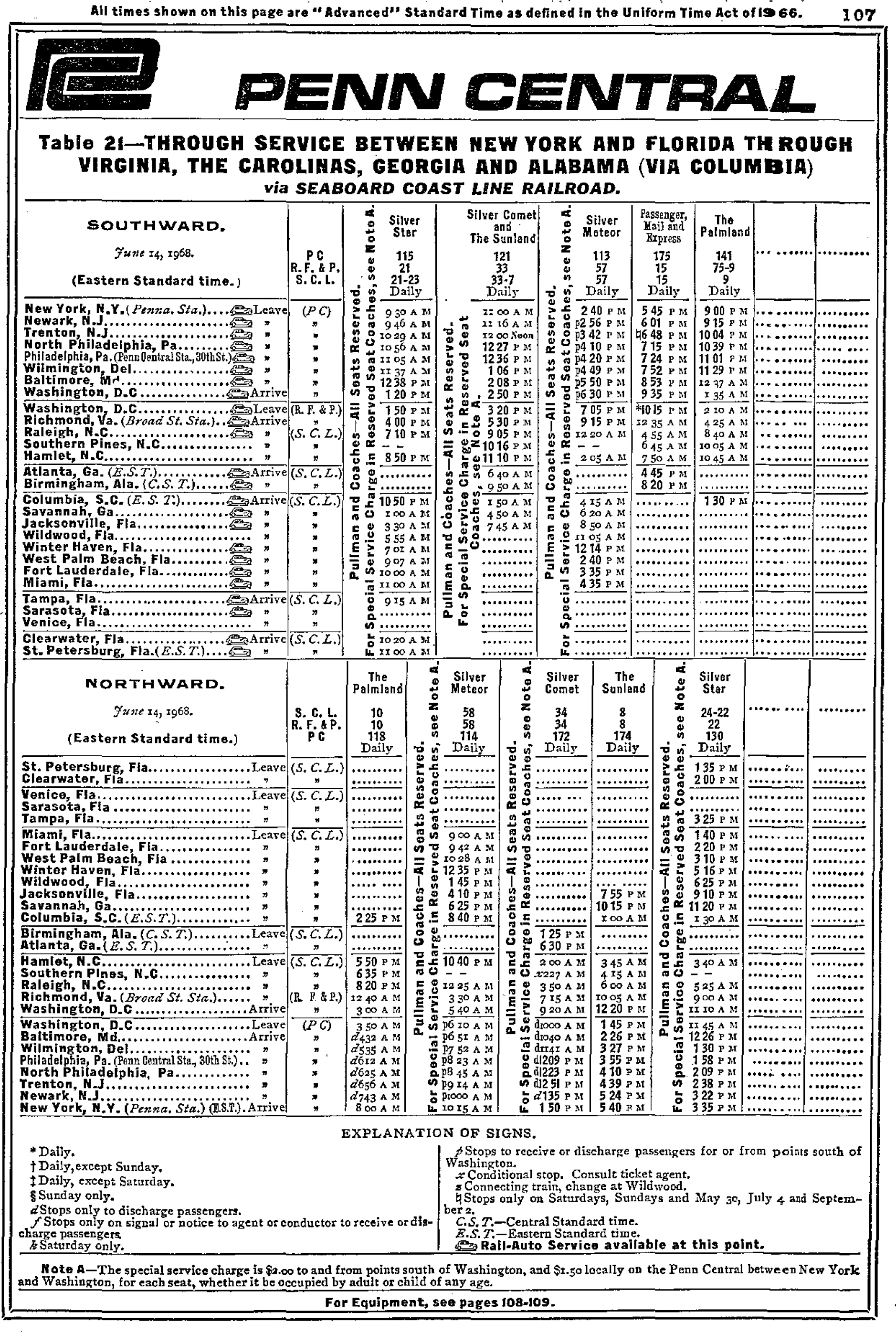

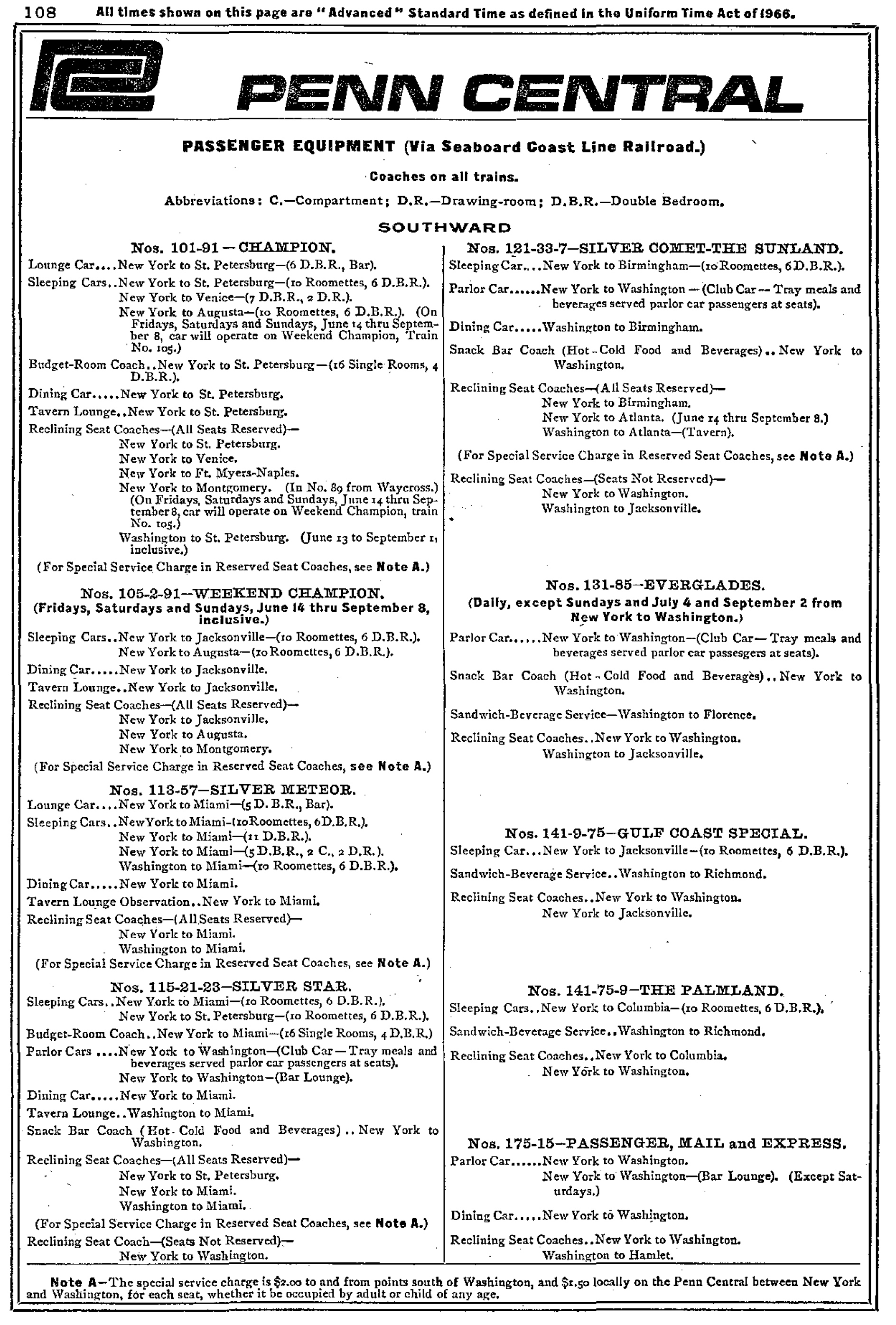

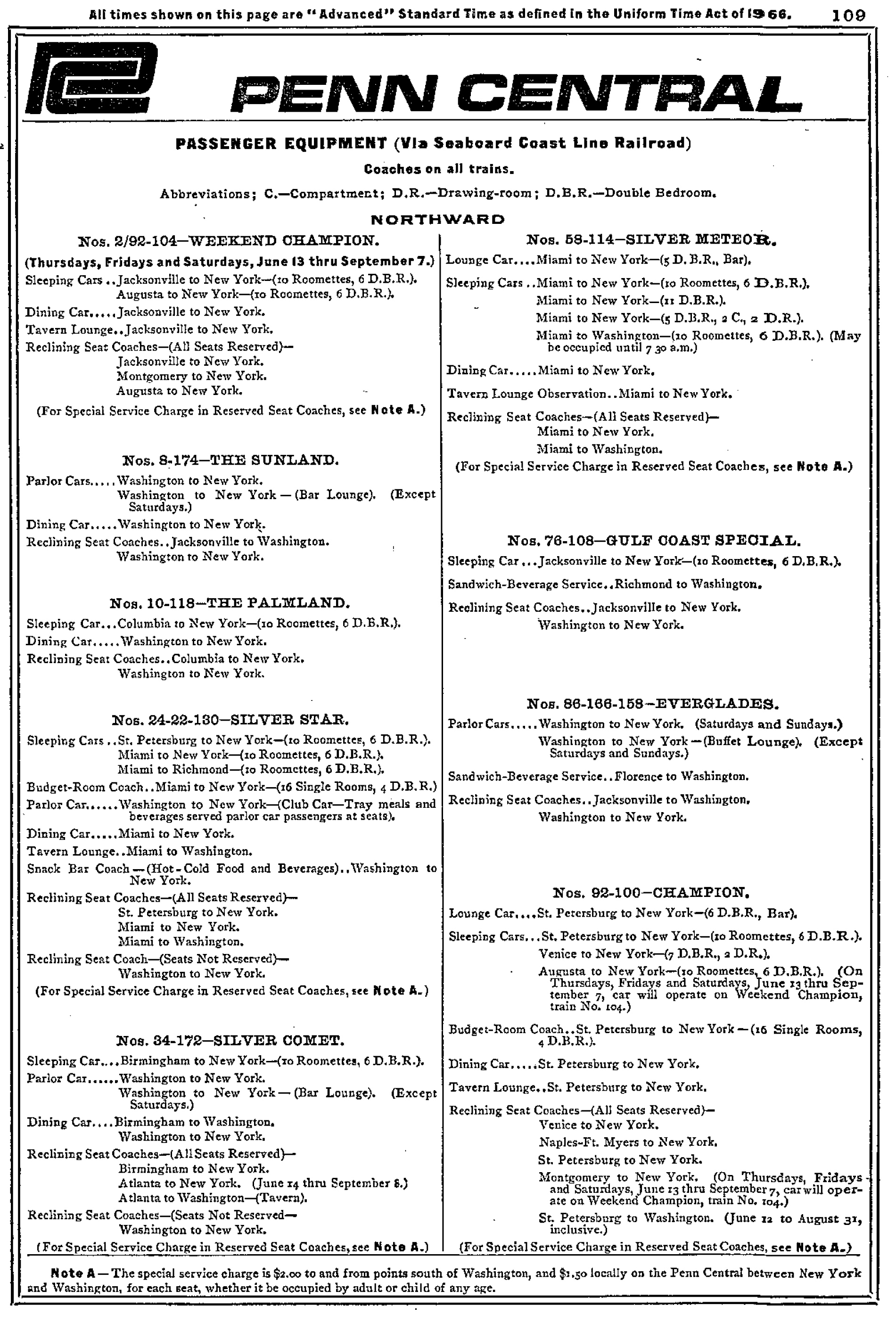

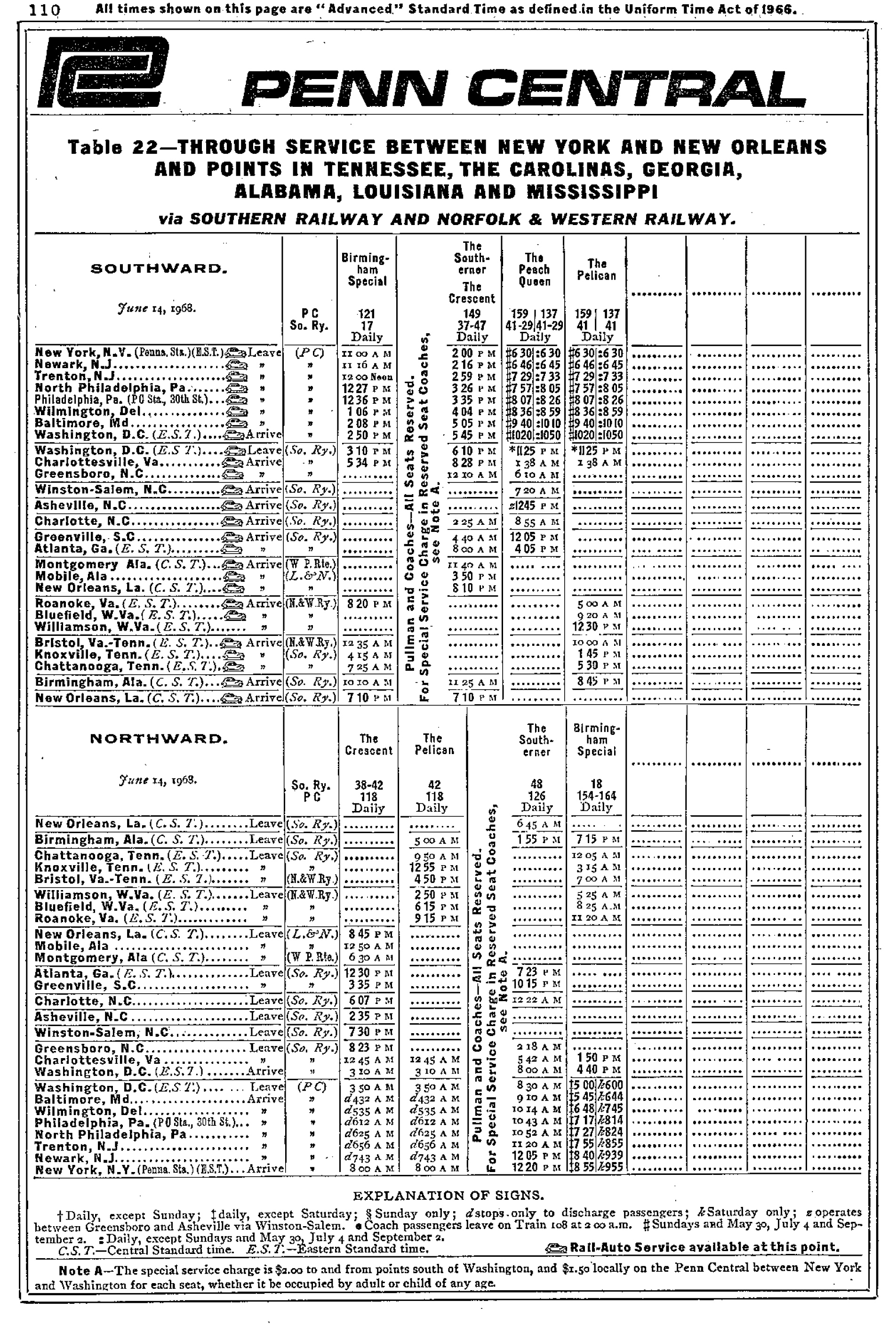

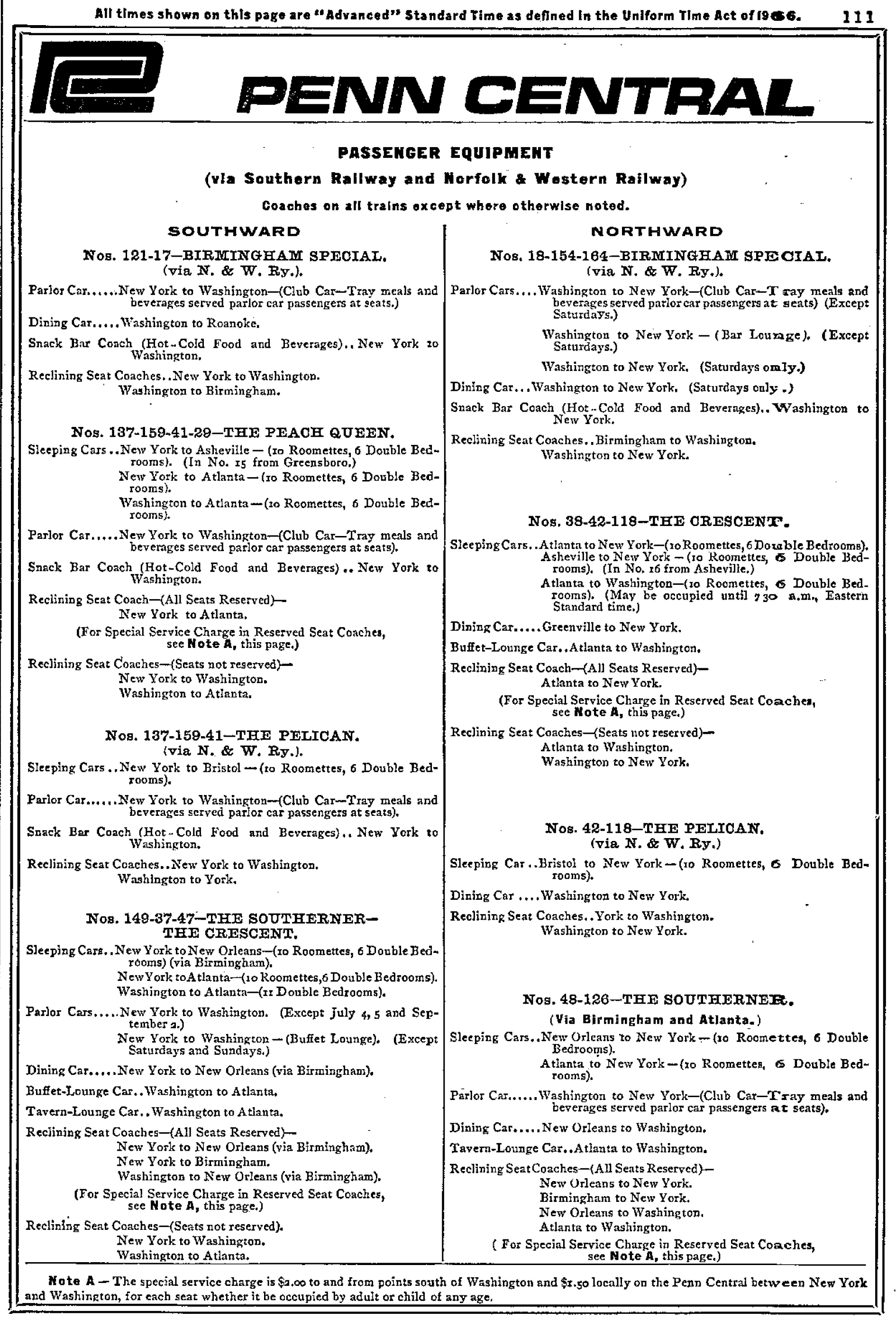

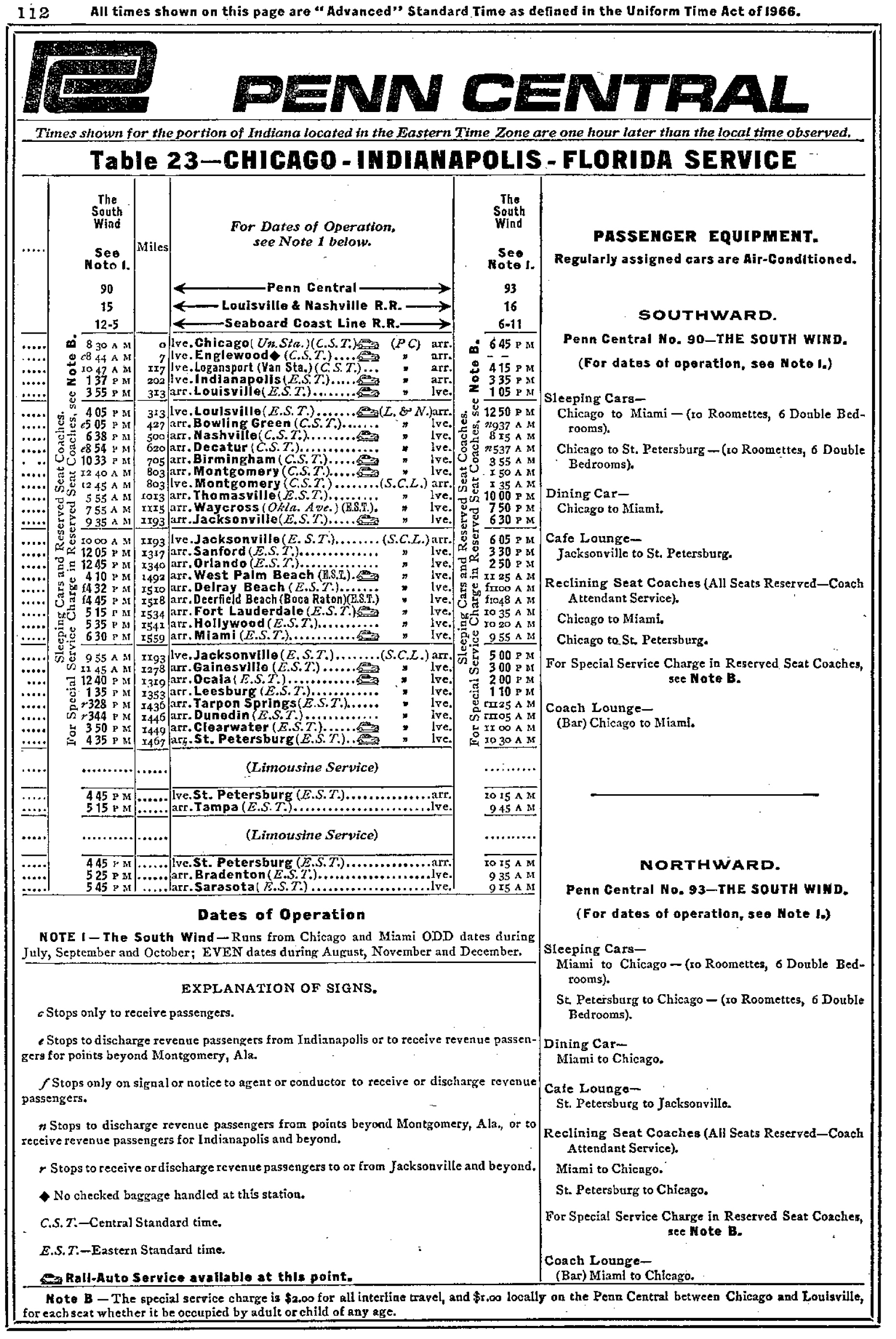

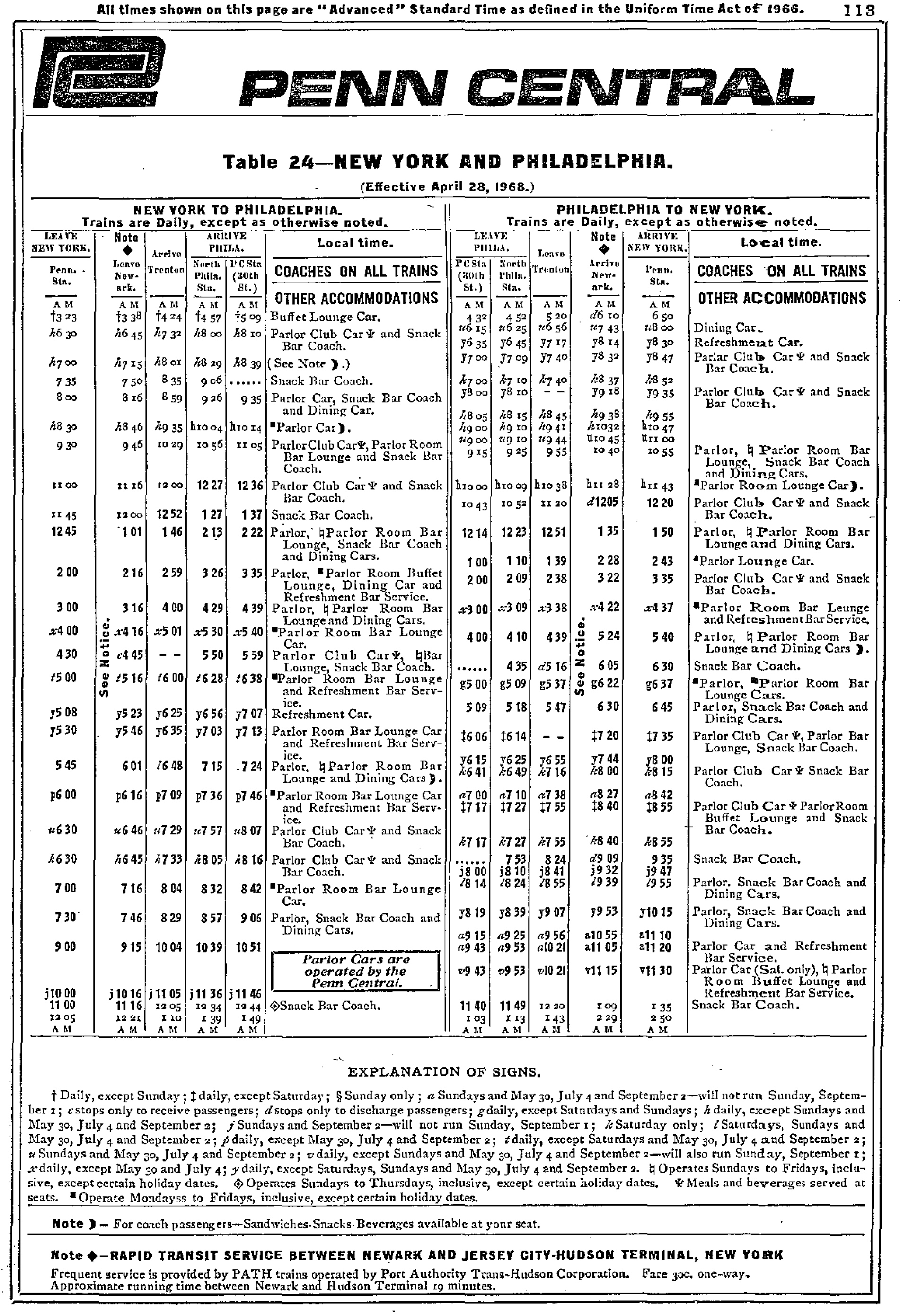

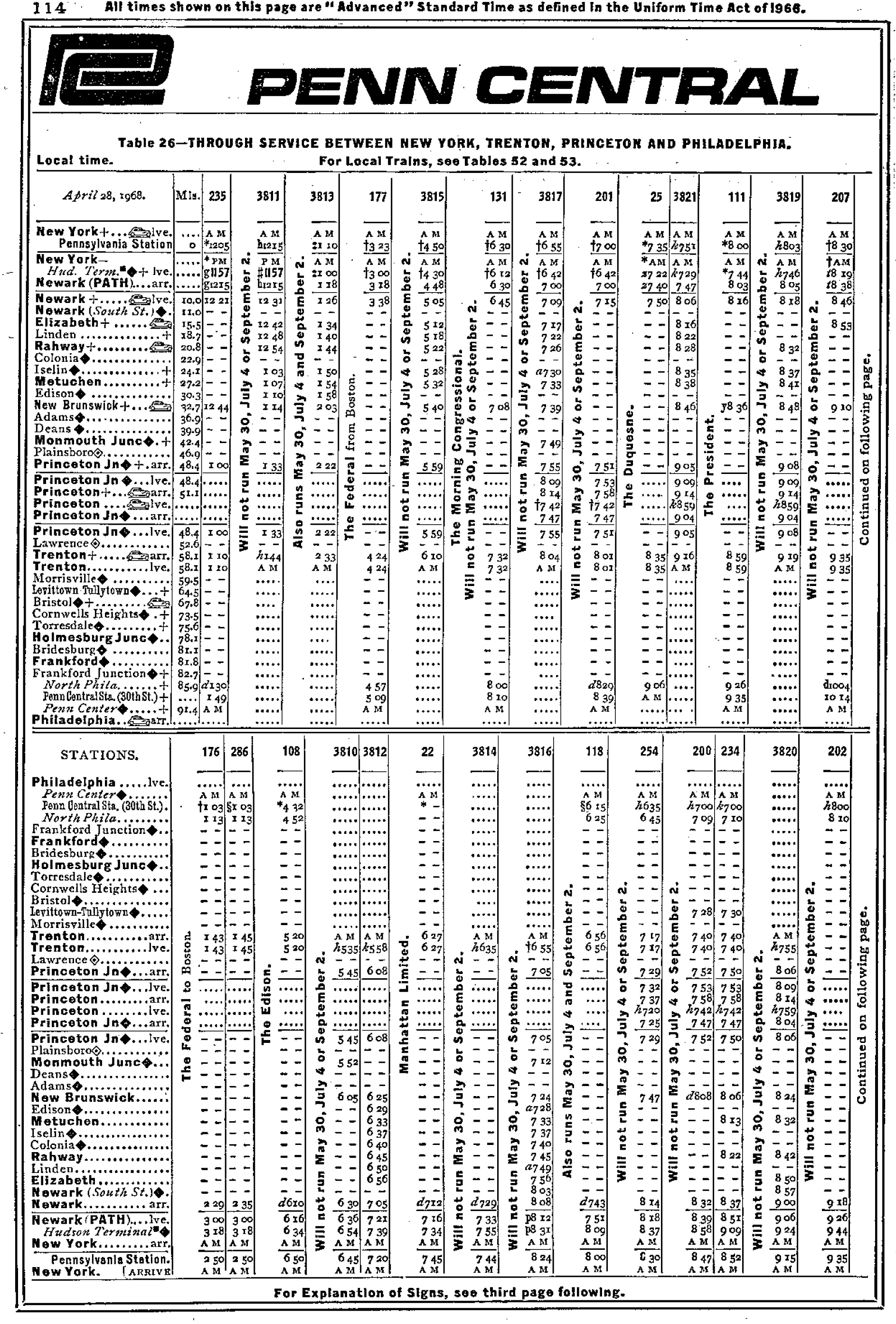

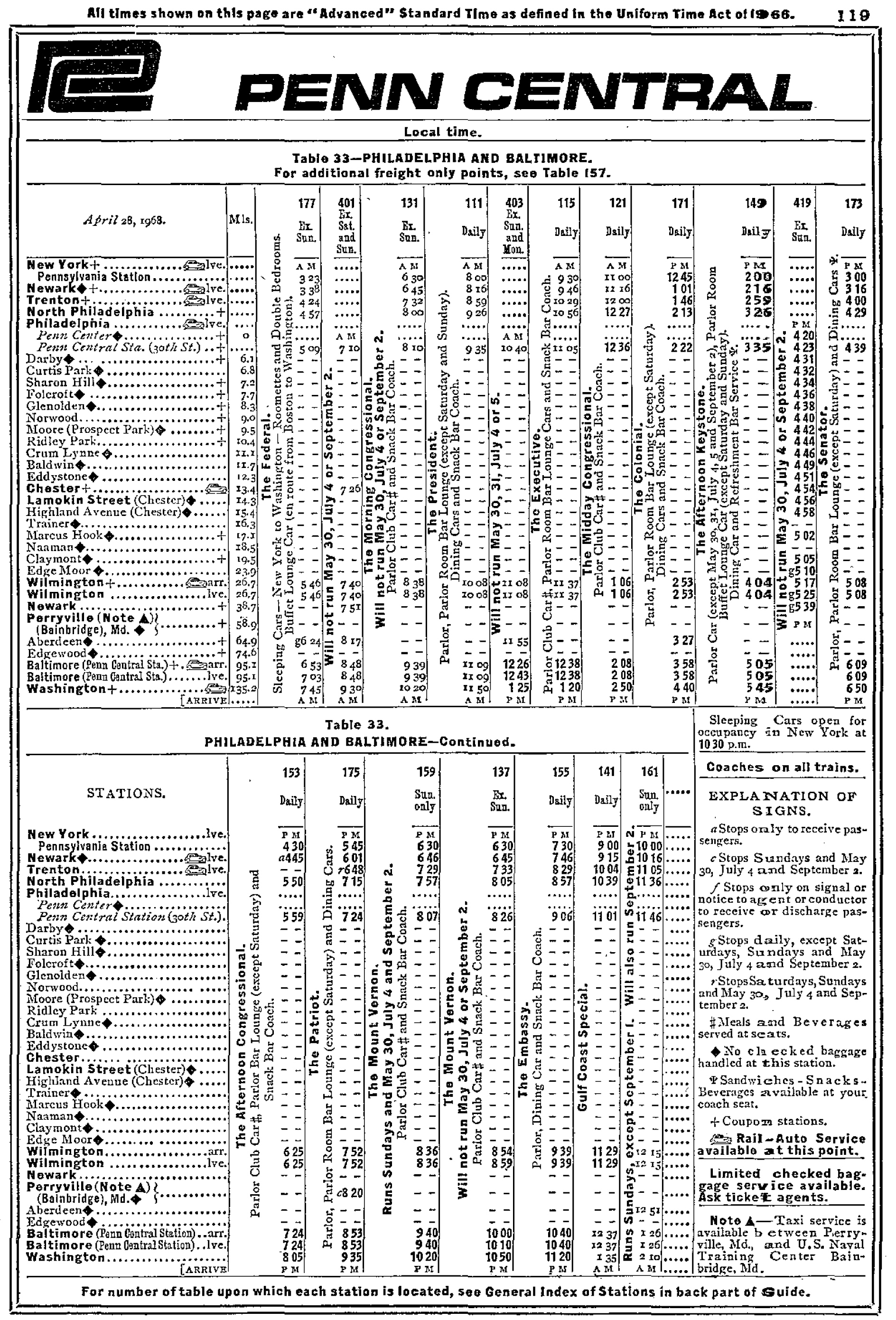

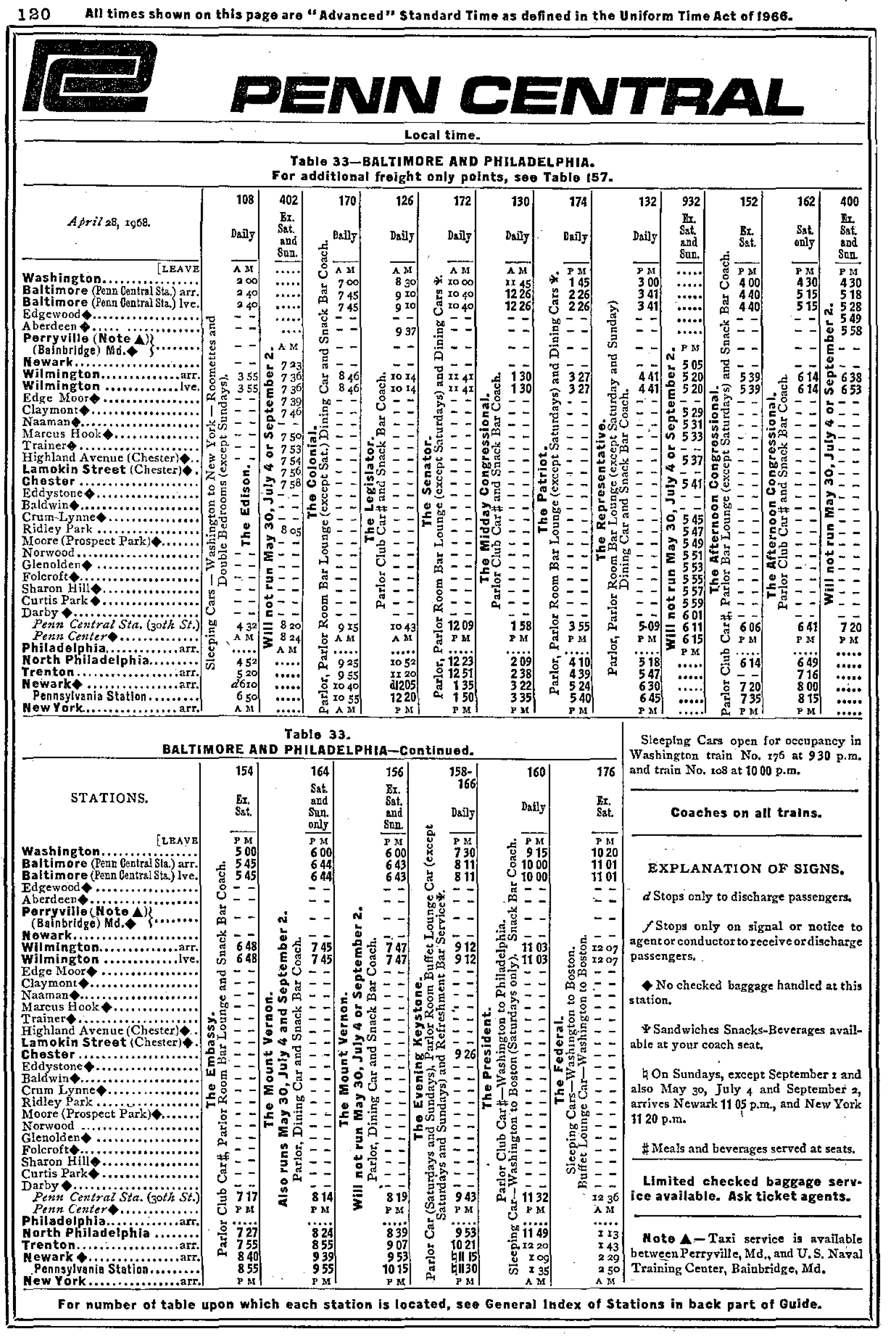

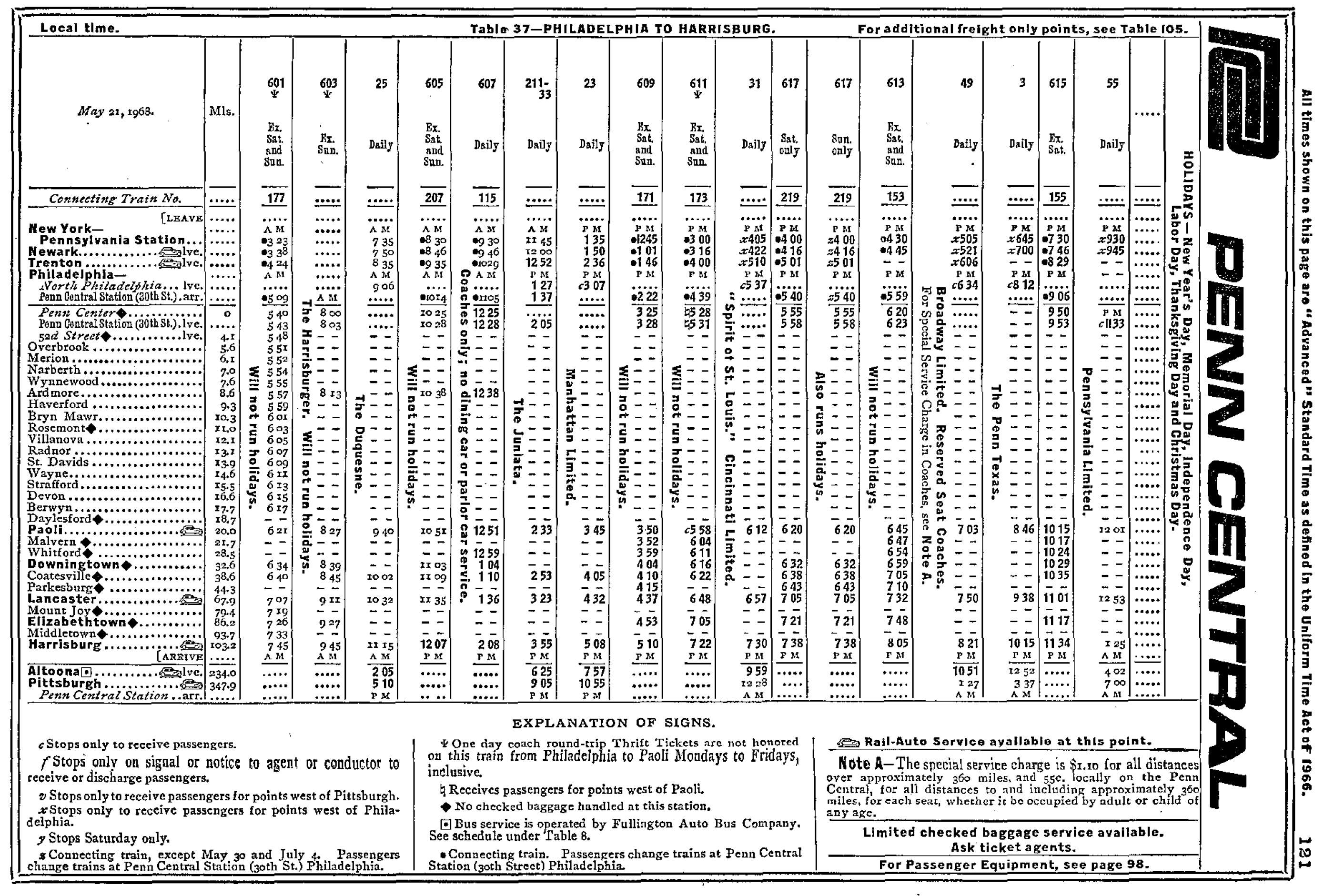

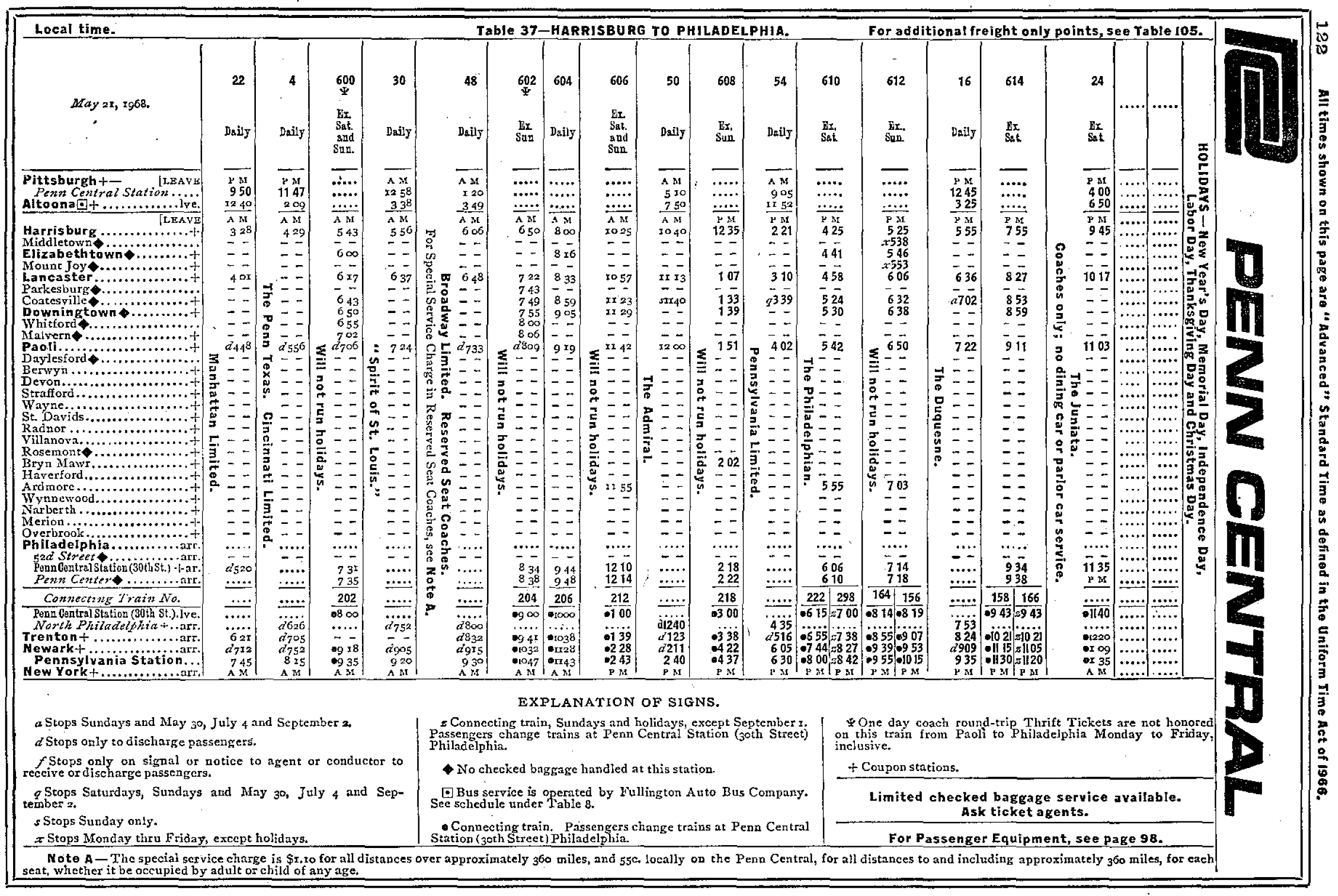

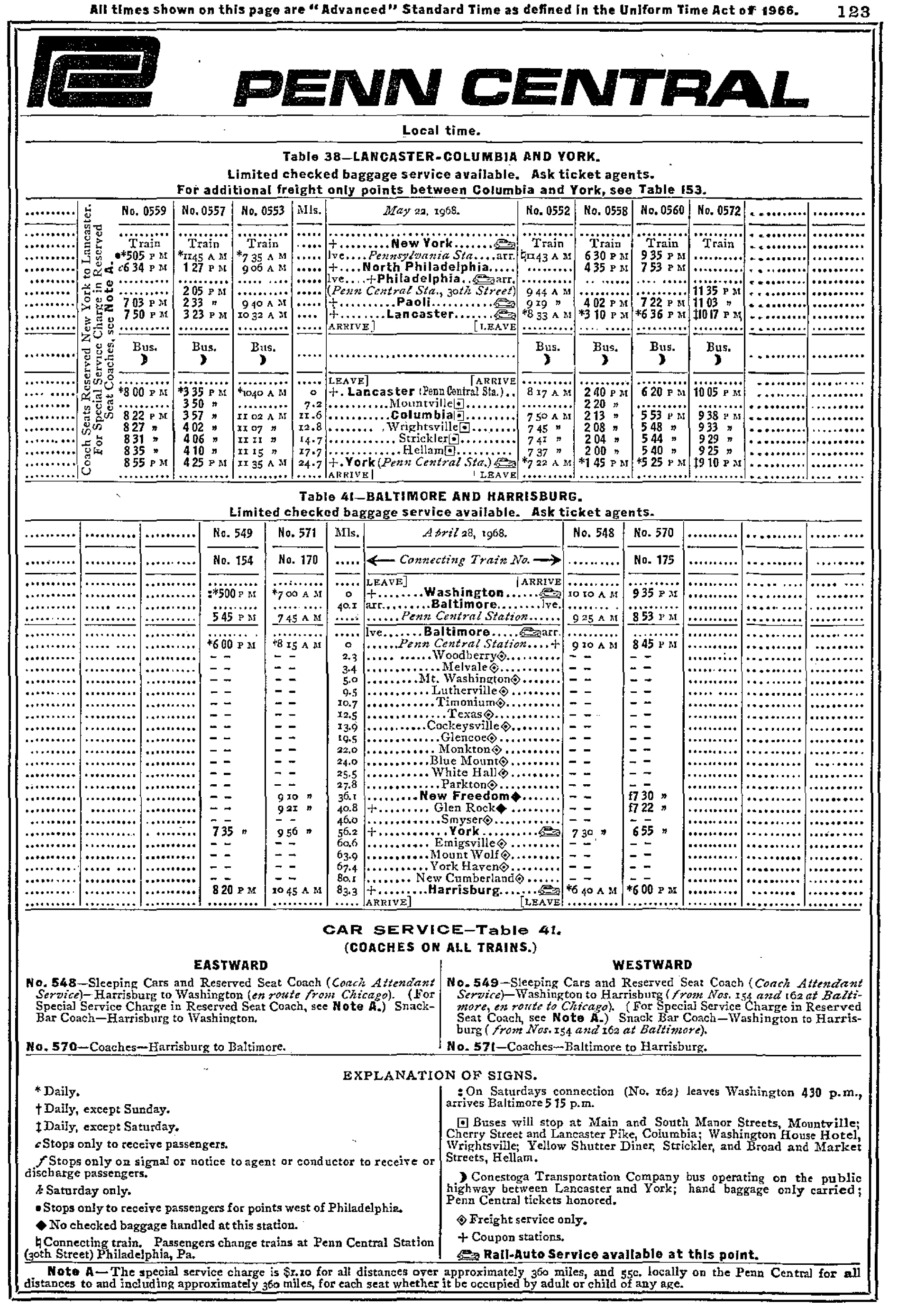

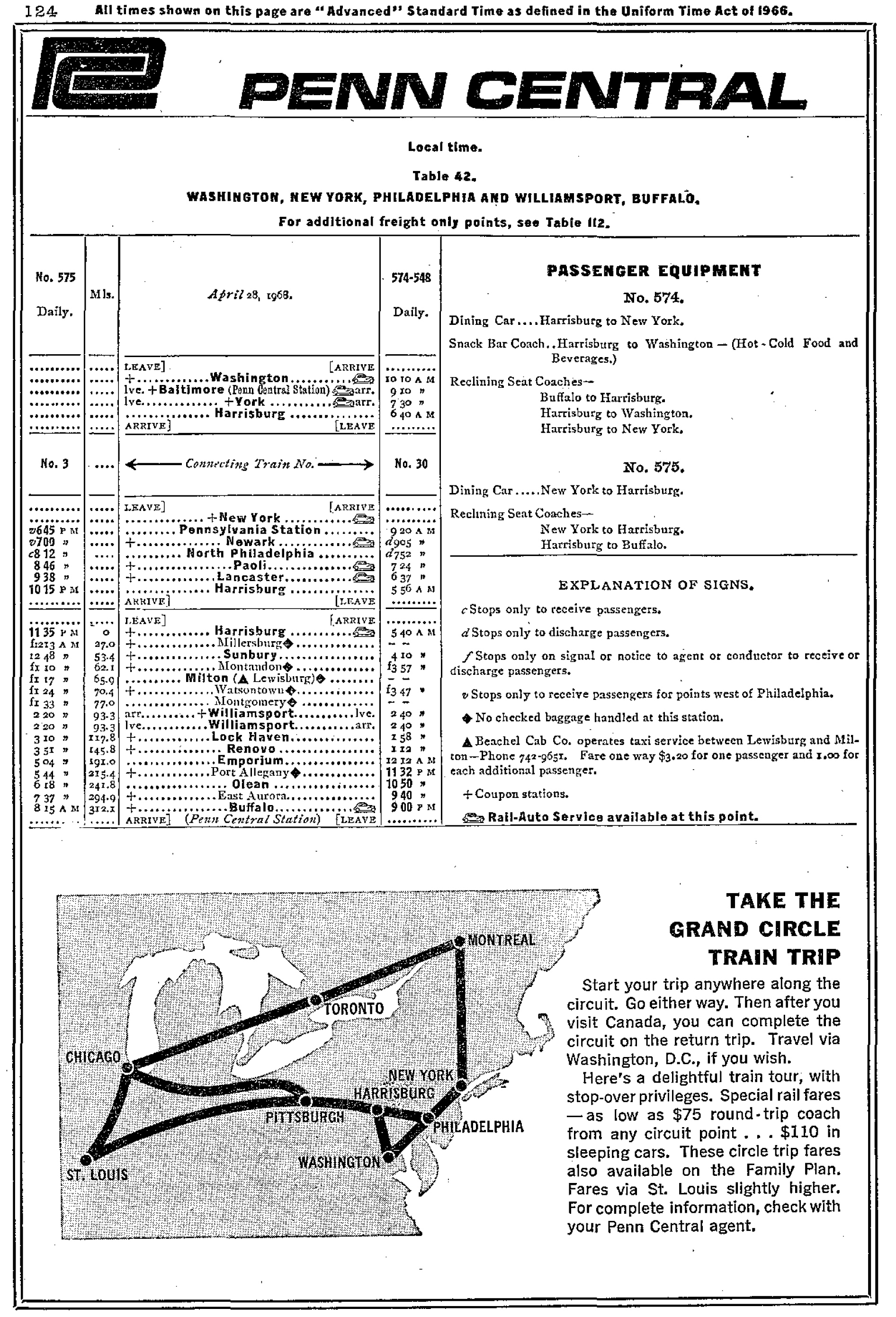

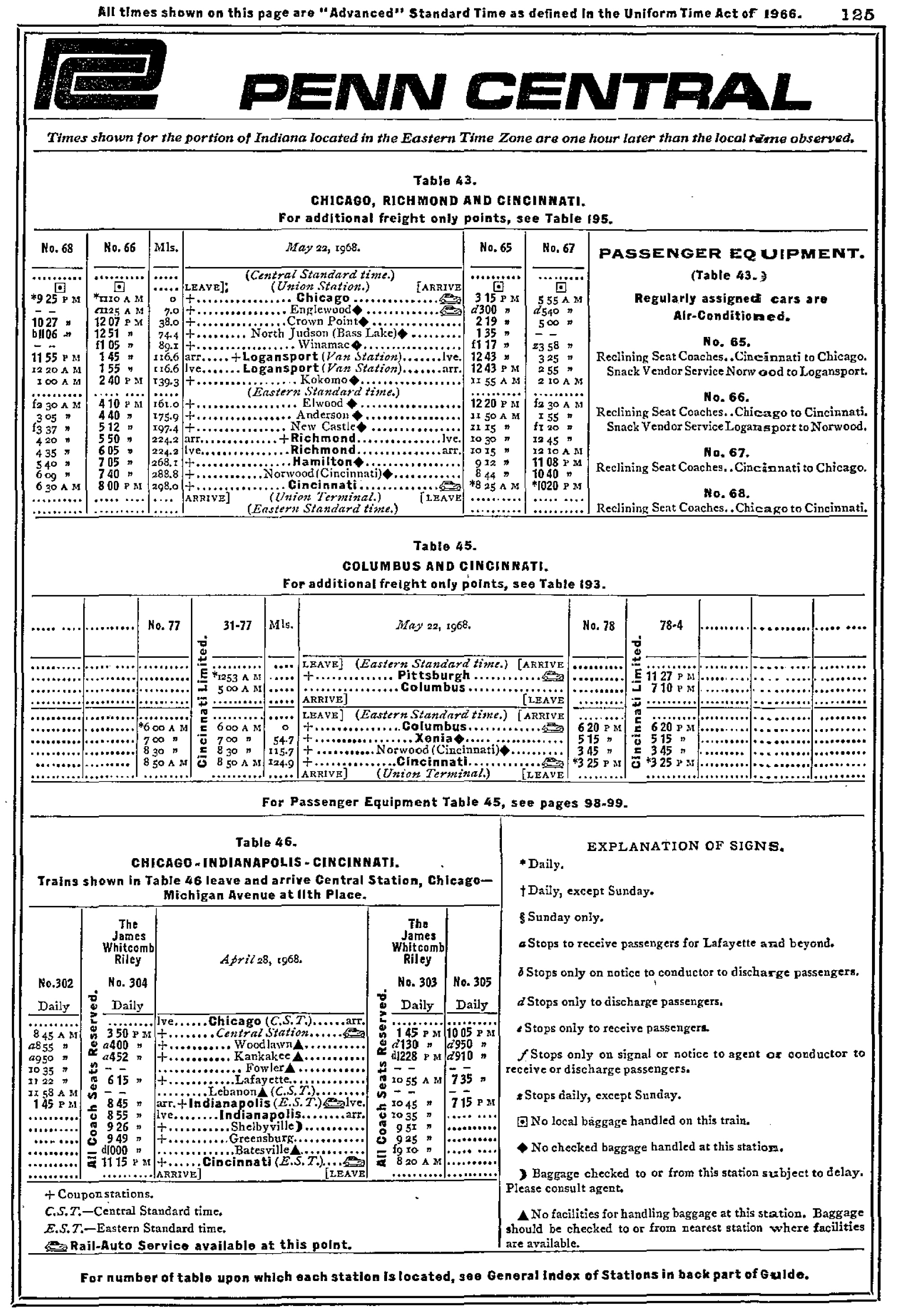

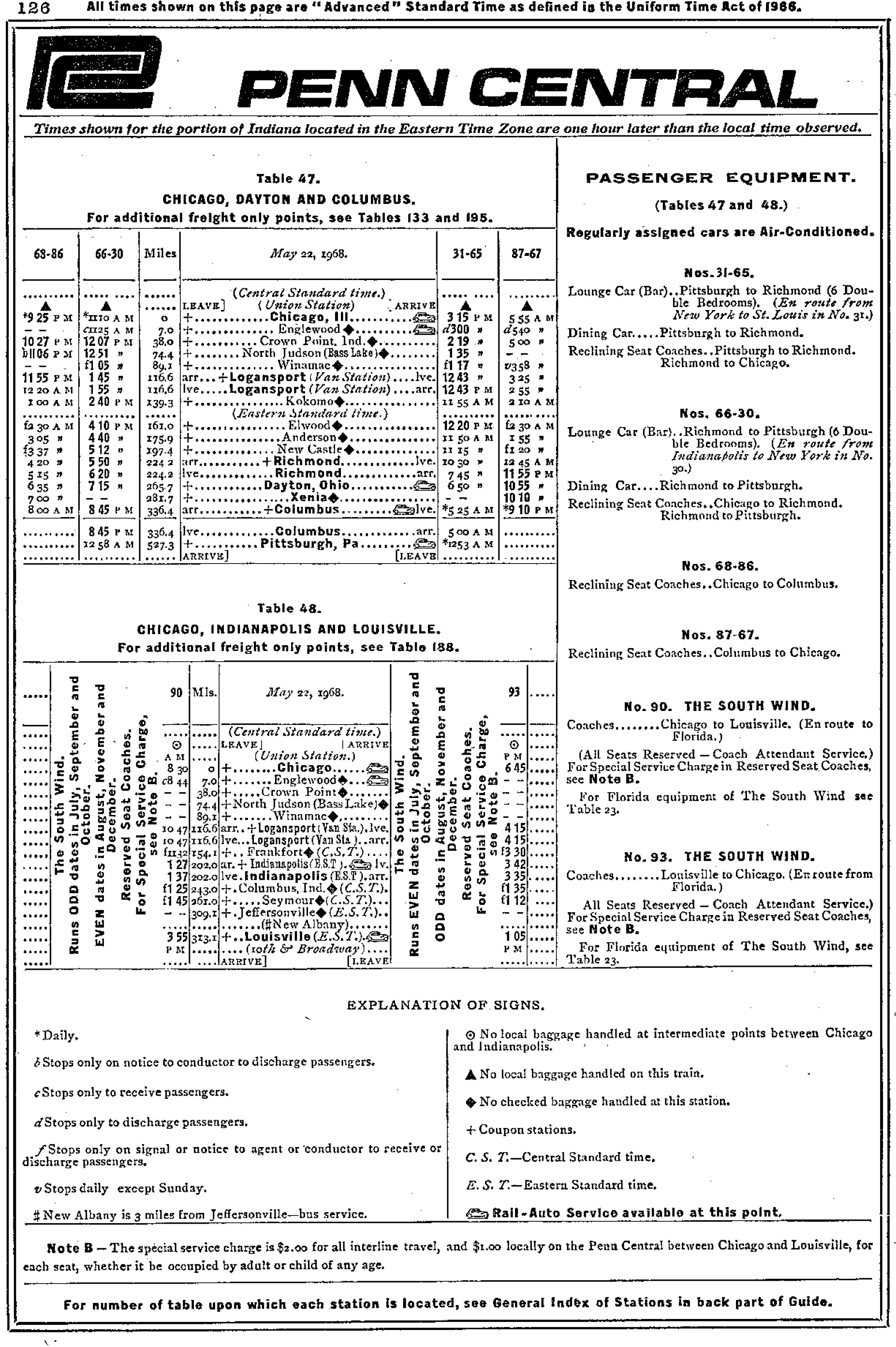

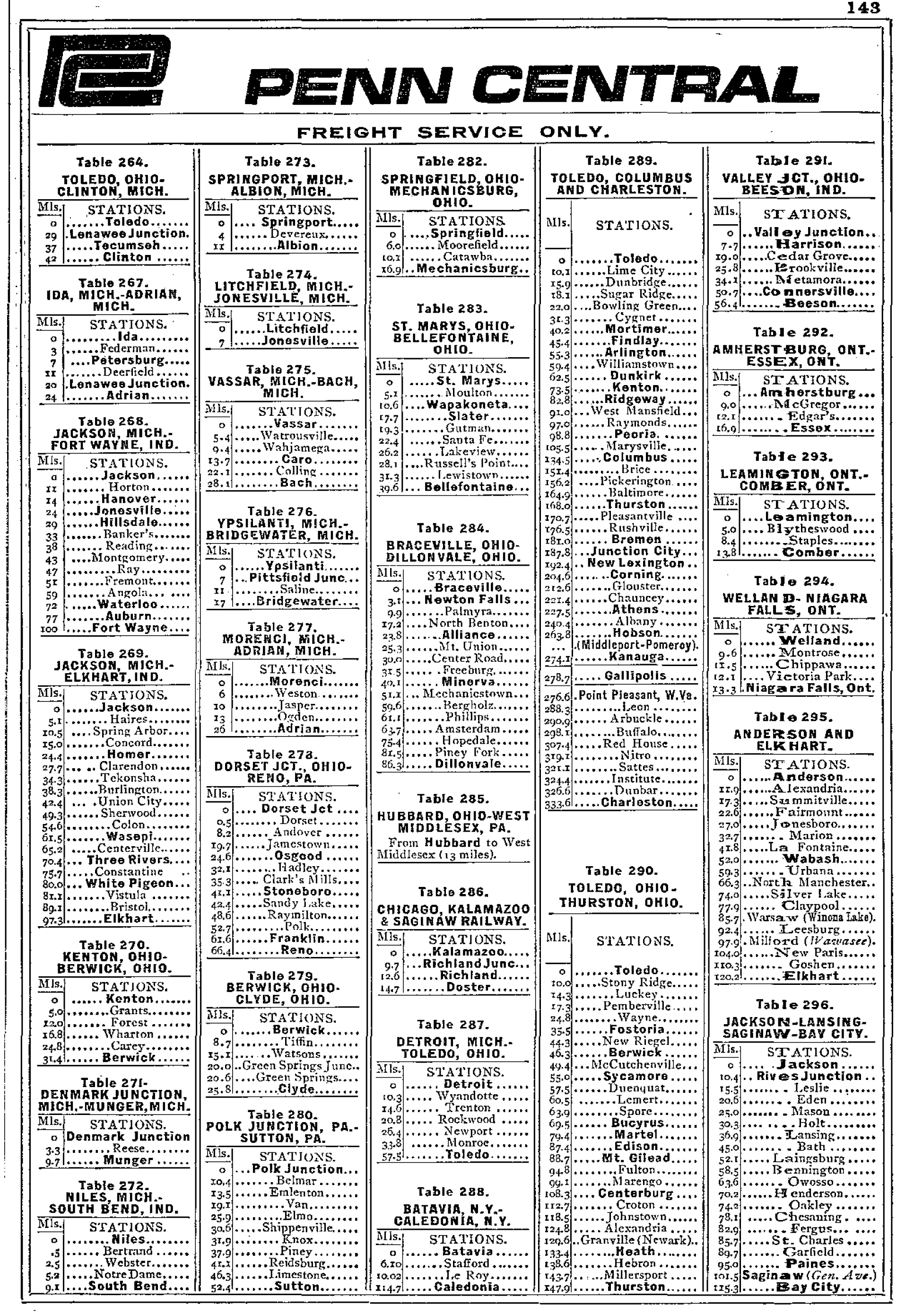

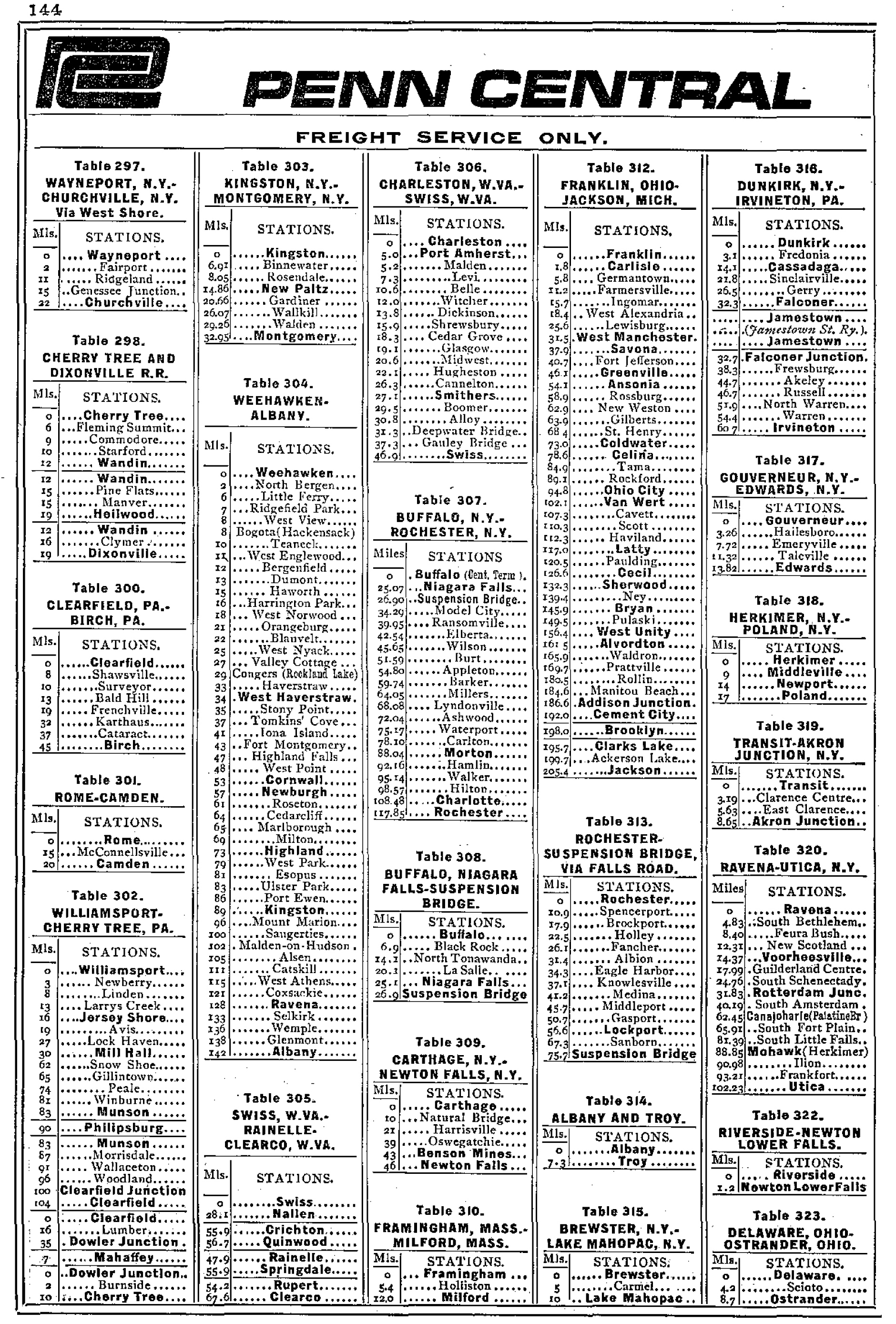

Timetables (July, 1968)

Recent Articles

-

Maine Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:58 AM

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad & Museum’s Ice Cream Train is a family-friendly Friday-night tradition that turns a short rail excursion into a small event. -

North Carolina Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 11, 26 11:06 AM

One of the most popular warm-weather offerings at NCTM is the Ice Cream Train, a simple but brilliant concept: pair a relaxing ride with a classic summer treat. -

Pennsylvania "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 12:04 PM

The Keystone State is home to a variety of historical attractions, but few experiences can rival the excitement and nostalgia of a Wild West train ride. -

Ohio "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:34 AM

For those enamored with tales of the Old West, Ohio's railroad experiences offer a unique blend of history, adventure, and natural beauty. -

New York "Wild West" Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:23 AM

Join us as we explore wild west train rides in New York, bringing history to life and offering a memorable escape to another era. -

New Mexico Murder Mystery Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 11:12 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails -

New York Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:09 AM

While CMRR runs several seasonal excursions, one of the most family-friendly (and, frankly, joyfully simple) offerings is its Ice Cream Express. -

Michigan Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 10, 26 10:02 AM

If you’re looking for a pure slice of autumn in West Michigan, the Coopersville & Marne Railway (C&M) has a themed excursion that fits the season perfectly: the Oktoberfest Express Train. -

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 10:07 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the…