- Home ›

- Landmarks ›

- Raton Pass

Raton Pass (New Mexico): Map, Route, History

Last revised: February 25, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Raton Pass is a mountain pass located in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the border of Colorado and New Mexico in the United States. It is a historically significant landmark, serving as a primary route for the Santa Fe Trail in the 19th century.

The pass is known for its steep grades, making it a challenging route for early settlers and later for the Santa Fe's main line. Today, the pass is also home to Interstate 25.

During the early 20th century the AT&SF completed the Belen Cutoff to the south which bypassed the mountains and cut across the northern plains of Texas.

The result of this work allowed for easier grades, faster transit times, and more efficient operations. Nevertheless, Raton remained an important corridor for years despite being listed as the steepest main line in the west.

Today, Raton sees less freight traffic from its peak years but it is currently still operated by successor BNSF Railway.

Photos

Roger Puta photographed Santa Fe F7A #309-L ahead of train #23, the westbound 'Grand Canyon,' at Raton, New Mexico on August 19, 1967.

Roger Puta photographed Santa Fe F7A #309-L ahead of train #23, the westbound 'Grand Canyon,' at Raton, New Mexico on August 19, 1967.History

One of the classic mountain rail grades is Santa Fe's Raton Pass. Located near the border of northeastern New Mexico and southern Colorado, the pass is home to the AT&SF's original transcontinental main line.

To acquire the pass required a fight with the Denver & Rio Grande, one of many duels between the two railroads during that time. The exploits of this war is detailed in Keith Bryant, Jr.'s excellent book, "History Of The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway."

During May of 1869 the Transcontinental Railroad was completed opening the west to trade and development. Following the completion of this line new railroads began spreading throughout the region, which included the Santa Fe and Denver & Rio Grande Railway.

The AT&SF had been building west from Topeka, Kansas since 1860 and the D&RG was chartered a decade later in 1870 hoping to connect Denver with El Paso, Texas and eventually Mexico.

On February 16, 1876 the Santa Fe reached La Junta, Colorado while the D&RG had arrived at Pueblo four years prior. At the time the pass was owned by Richens Lacy "Uncle Dick" Wootton, who had lived in the region since the 1850s.

Railroad War

William Barstow Strong became Santa Fe's president in 1877 and he immediately went to war with General William Palmer, owner of the D&RG, for control of the 7,834-foot Raton Pass.

After the Strong caught wind of Palmer's intentions to build through the pass he sent company engineer Albert Robinson and Location Engineer Ray Morley, using a D&RG train no less, to El Moro near Trinidad, Colorado where they would scout their own route.

In the process they hoped to gain Wootton's permission for first rights to build a rail line over the pass. At the time "Uncle Dick" owned a 27-mile toll road over Raton. His home was also based here as well as a small hotel.

Morley subsequently befriend Wootton, and he agreed to sell his enterprise to the Santa Fe. When D&RG's team showed up to claim it the pass for themselves he helped turn away the invaders.

Santa Fe 2-10-2 #1695 (a 1912 product of Baldwin) works helper service over Raton Pass as the big engine shoves on the rear of a long manifest freight, circa 1954. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Santa Fe 2-10-2 #1695 (a 1912 product of Baldwin) works helper service over Raton Pass as the big engine shoves on the rear of a long manifest freight, circa 1954. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Ultimately, the D&RG gave up on its intentions to continue building south and instead constructed a line to the west over Tennessee Pass through Colorado's Royal Gorge.

While the Santa Fe may acquired the rights to Raton it was still in the difficult position of actually building a railroad over the pass.

The AT&SF originally completed a line over the mountain in 1878, a temporary and torturous route that featured switchbacks, 6% grades, and curves as sharp as 16 degrees.

Completion

In 1879 crews were able to finish the 2,041-foot tunnel over Raton, which eliminated the switchbacks and greatly reduced ruling grades. However, the AT&SF was still forced to deal with grades reaching as high as 3.5% in New Mexico and 4% in Colorado.

After finally conquering Raton, Santa Fe continued eastward through New Mexico and eventually reached Arizona and much of California. All of this effort was carried out under Strong, who is still considered one of the railroad's greatest presidents.

Years later the railroad double-tracked much of Raton and constructed a second, 2,787-foot bore through the mountain that featured grades of just 0.158%.

For all of the improvements, Raton was always an operational headache for the Santa Fe, as was any main line that featured grades above 3%.

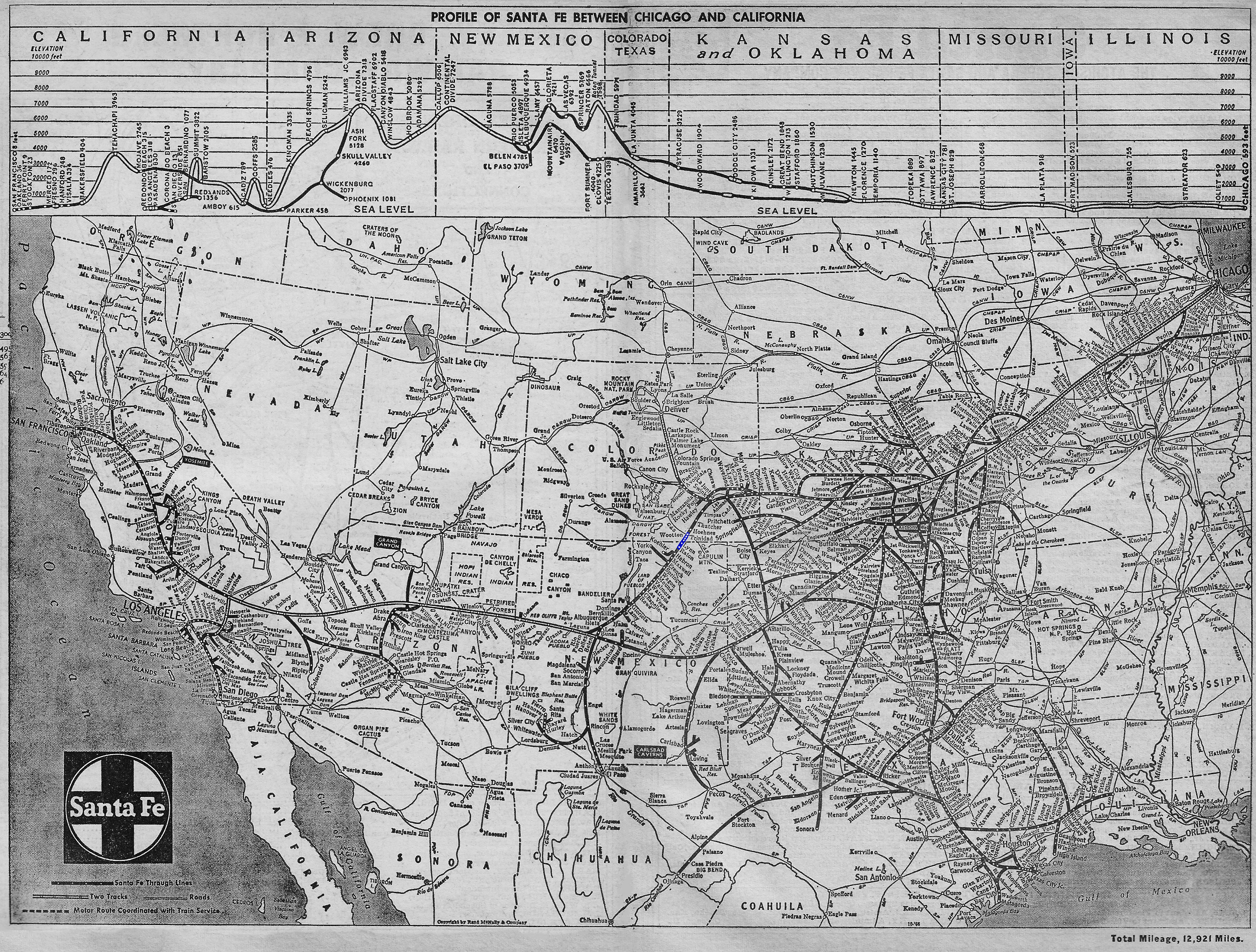

Route Map

In 1907 the AT&SF opened Belen Cutoff, a 200+ mile main line that cut across the open plains of eastern New Mexico and the Northern Panhandle of Texas.

This new route diverted most of the railroad's transcontinental traffic off of Raton. However, the original line continued to see several trains per day including the crack Super Chief and El Capitan as well as several coal trains from nearby mines.

During the steam era one could regularly witness double-headed 2-8-8-2s and 2-10-2s tackling the grades either moving freights or assisting passenger consists.

As the years have passed train movements have ebbed and flowed over Raton Pass. Today, it has lost much of the local coal movements that once moved steadily out of the region. Additionally, much of the priority traffic has been picked up over Belen and the Transcon route.

A pair of Santa Fe locomotives, lead by 2-10-2 #3815, double-head a long freight over Raton Pass, circa 1950. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Santa Fe locomotives, lead by 2-10-2 #3815, double-head a long freight over Raton Pass, circa 1950. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Today

Still, Raton refuses to give up the ghost and today acts primarily as a relief valve occasionally seeing hot-shot movements such as "Z"-symbolled intermodals or United Parcel Service (UPS) pre-blocked movements.

There is also Amtrak's Southwest Chief which continues to use the line. Most other trains passing over Raton are strings of empty coal hoppers or "bare-table" well cars (intermodal).

It is interesting to wonder what the future holds for the country's

steepest main line still in operation although it appears that for now

we will continue to see the latest locomotives tackle Santa Fe's

original transcontinental route to the west coast.

(Thanks to "Raton Panorama" from the August, 1946 issue of Trains, "Crown Of The Santa Fe" by William Diven from the February, 1997 issue of Trains, and "Raton Passed" by William Diven from the November, 2005 issue of Trains as primary references for this article.)

Additional Sources

- Bryant, Jr. Keith L. History Of The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1974.

- Glischinski, Steve. Santa Fe Railway. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2008.

- Yenne, Bill. Santa Fe Chiefs. St. Paul: TLC Publishing Company, 2005.

Recent Articles

-

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail. -

Duffy's Cut: A Forgotten Railroad Tragedy

Jan 29, 26 11:05 AM

Duffy's Cut is an unfortunate incident which occurred during the early railroad industry when 57 Irish immigrants died of cholera during the second cholera pandemic. -

Wisconsin Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:47 PM

This article delves deep into the passenger and commuter train services available throughout Wisconsin, exploring their history, current state, and future potential. -

Connecticut Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:30 PM

Connecticut's passenger and commuter train network offers an array of options for both local residents and visitors alike. Learn more about these services here. -

South Dakota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:29 PM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:23 PM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Florida ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:18 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards.