Rio Grande Southern Railroad, The Fabled Narrow-Gauge

Last revised: July 29, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The state of Colorado was filled with a near-endless list of fabled narrow-gauge systems. One of the last built, largest, and longest to remain in service was the Rio Grande Southern.

The RGS was conceived by Otto Mears to tap the region's rich silver ore trade. Unfortunately, the road's success was very short-lived due to the Sherman Silver Purchase Act's repeal in 1893.

In addition, the RGS suffered from stiff grades and tight curves. While not uncommon for a narrow-gauge system, particularly those operated in Colorado, the railroad's route was quite circuitous between its end terminal points.

Only a few years after operations began the RGS entered voluntary bankruptcy and was ultimately acquired by the then-Denver & Rio Grande Railway.

The D&RG, and later Denver & Rio Grande Western, continued to operate the RGS network for more than a half-century. During this time the railroad subsisted on a variety of freight from coal and livestock to various ores and other valuable metals.

Finally, with the loss of its two largest customers and a bleak future, operations were suspended in the early 1950s with track removed shortly thereafter. Today, traces of the old RGS network are still quite visible in this rural and rugged area of the San Juan Mountains.

Photos

Shortly before discontinuing all operations, Rio Grande Southern 2-8-2 #461 was photographed here in front of the Union Station at Ridgway, Colorado by Richard Kindig on September 5, 1951. This little Mikado was scrapped in 1953.

Shortly before discontinuing all operations, Rio Grande Southern 2-8-2 #461 was photographed here in front of the Union Station at Ridgway, Colorado by Richard Kindig on September 5, 1951. This little Mikado was scrapped in 1953.History

The proliferation of three-foot, narrow-gauge railroads throughout Colorado is credited largely to the success of General William Jackson Palmer's Denver & Rio Grande Railway.

The D&RG was envisioned to accomplish three goals:

- Open a main line from Denver to El Paso, Texas via the Front Range. The railroad would follow the Rio Grande River much of the way and utilize New Mexico's Raton Pass.

- Complete a secondary main line to a connection with the Central Pacific/Southern Pacific at Ogden, Utah.

- Establish robust secondary lines into the San Juan Mountains' rich mining district, located in southwestern Colorado and northwestern Mexico. Silver was the primary ore here, although gold and lead were also extracted in profitable quantities.

The narrow-gauge concept gained traction in the 1870s as a cheaper alternative to standard gauge construction, which promoters boasted could be built at one-fifth the cost of major eastern trunk lines like the Baltimore & Ohio, Erie, and Pennsylvania. In addition, it was believed three-foot systems (and their various counterparts) would enjoy lower operating costs (which proved largely untrue).

For the D&RG it was originally intended as a stand-alone, isolated railroad except for its Denver connections. Ultimately, Palmer failed to reach El Paso but his system nevertheless became quite successful.

At its peak it enjoyed a robust narrow-gauge network spanning 1,861 miles by 1890. Much of the D&RG was later converted to standard gauge; only the San Juan District, and a few branches, remained three-foot after World War II.

The lucrative mining operations in the San Juans eventually lured other narrow-gauge endeavors. Some were built due west out of Denver while others were constructed specifically to link up with the D&RG.

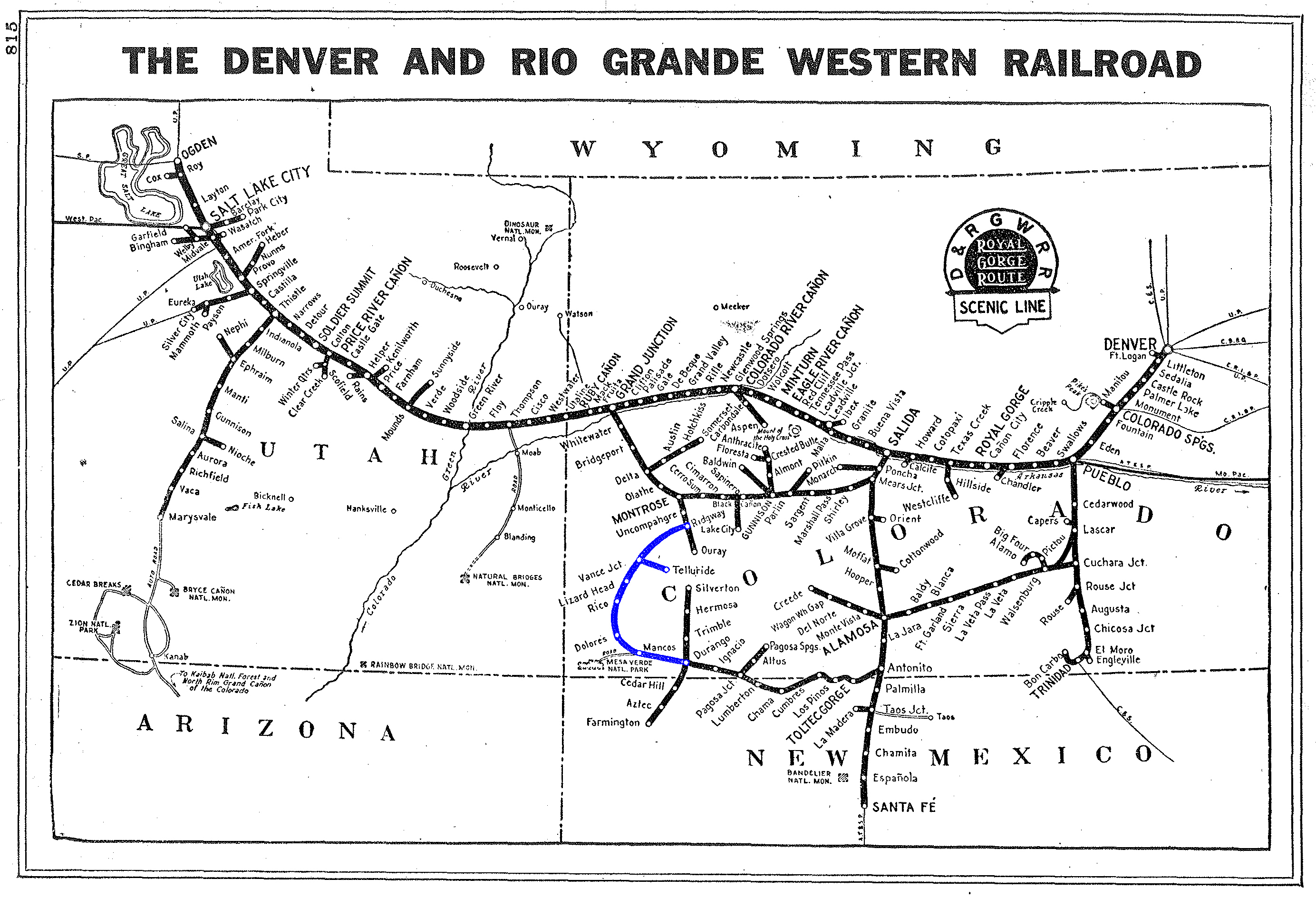

System Map (1930)

As historian Dr. George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the success of Palmer's railroad and the ability to interchange with it, is predominantly what drove investors to build their systems as three-footers.

There were also no other through railroads located within this rugged, and sparsely populated region of Colorado, making the D&RG the only plausible road with which to do business.

While there was the added incentive of cost savings during construction this really never materialized on a substantial level. In addition, the extensive studies noting such were later proven wrong.

Otto Mears

Otto Mears was already an affluent entrepreneur by the time he founded the Rio Grande Southern, having been successful in southwestern Colorado's mining trade.

He had also operated a series of profitable toll roads in the region between Silverton and Ouray. The extremely rugged San Juan Mountains, with some peaks reaching over 10,000 feet, made efficient transportation here nearly impossible.

That had finally changed with the Denver & Rio Grande. In response, Mears sought to convert his toll roads into narrow-gauge railroads which would connect with the D&RG.

In addition to serving the mining industry, Mears projected to connect both the D&RG's Marshall, and Cumbres Pass lines. Doing so would establish a north-south route through the San Juans.

Silverton Railroad

The Silverton Railroad (SRR) would spearhead Mears' effort with work beginning north out of Silverton, Colorado. The SRR was incorporated on June 5, 1887 and by year's end had completed 5 miles. Its initial goal was to serve the Yankee Girl Mine, 11 miles away.

After summiting Red Mountain Pass, with an uncompensated 5% grade, the SRR had reached the mine in late October, 1888. The original route continued north and was deemed complete in the spring of 1889. It spanned 18 miles in all, from Silverton to Albany, serving additional mines along the way (Albany was a mining camp located about a mile north of Ironton; this spur was removed in 1892 when the Saratoga Mill closed).

In 1888, with the silver trade booming, the Silverton Railroad was authorized to continue north to Ouray. Charles W. Gibbs, the Silverton's chief engineer, had been ingenious in his ability to keep grades manageable to the point that rail service was at least practical.

However, he could find no manageable grade down Uncompahgre Canyon into Ouray. The best option was an 8% descent, or drop of 2,100 feet in just 5 miles. This would have made traditional steam railroading impossible.

With the repeal of the Sherman Silver Act in 1893, tonnage sharply declined on the Silverton Railroad and management filed for abandonment on August 9, 1921. The request was approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission on June 17, 1922 and rails were removed in 1926.

Silverton Northern Railroad

Interestingly, Mears formed this road in response to the silver trade's collapse. The Silver Sherman Purchase Act (its official title, often shortened to Silver Sherman Act) had originally been signed into law on July 14, 1890.

It stipulated the government would purchase large quantities of silver bullion to fight deflation and help promote economic expansion.

The act specified for the issuance of legal tender notes sufficient in amount to pay for 4.5 million ounces of silver bullion each month, at the prevailing market price. Such large sums meant silver was now big business and southwestern Colorado was rich in the metal.

Unfortunately, the plan had the unintended consequence of draining the country's gold reserves, which had been used to purchase the silver. This complication, coupled with other factors, caused the financial Panic of 1893 (in part due to a fear the gold standard would be abandoned) and ultimately led to the act's repeal.

To combat the loss of silver ore, Mears organized the Silverton Northern on September 20, 1895 to serve a gold mine north of Silverton along the Animas River.

Interestingly, when the road was formed, it already had 2 miles of track in service to the Waldheim Mine. This short branch had been completed by the Silverton Railroad in 1893 and was transferred to the new SN.

In June, 1896 the SN was extended to Eureka, serving the Sunnyside Mine (its largest customer) there, and later reached as far as Animas Forks in 1904.

This latter segment contained a blistering ruling grade of nearly 7% with an overall grade of 5.77%. Obviously, trains on this section were short with only one load of coal capable of moving up the line to Animas Forks (at 4 mph) and three loads of ore coming down.

The SN would also build a 1.3 mile spur from Howardsville to serve the Green Mountain and Old Hundred mines, which opened in 1905.

Operations on the northern section above Eureka survived until 1922 with the southern end holding out until 1939 when the Sunnyside Mine closed. Final abandonment of the Silverton Northern was approved on August 31, 1941 with rails removed in October, 1942.

Interestingly, because the road had handled gold ore it survived longer than its nearby counterpart, the Silverton Railroad.

Rio Grande Southern 2-8-0 #74 has cutoff from its excursion at Vance Junction, Colorado in the summer of 1950. This location was where the Telluride Branch joined the main line. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande Southern 2-8-0 #74 has cutoff from its excursion at Vance Junction, Colorado in the summer of 1950. This location was where the Telluride Branch joined the main line. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.Rio Grande Southern

Otto Mears incorporated the Rio Grande Southern Railroad (RGS) on November 5, 1889. After being stymied by Uncompahgre Canyon from both ends, he was determined to finally complete the north-south routing to connect the Denver & Rio Grande's Marshall Pass and Cumbres Pass lines.

Interestingly, the RGS would ultimately require 162 miles to do so although Ouray, and the end-of-track at Irondale on the Silverton Railroad, were a mere 12 miles apart. A direct route from Ridgway-Ouray-Durango would have required just 83 miles; today, this alignment is utilized by Highway 550.

Construction of the RGS was initiated from both ends; the northern segment from Dallas Junction (later Ridgway) began grading on March 19, 1890 and was completed to Telluride on November 23rd that same year, a distance of 45 miles.

Work began out of Durango in the latter half of 1890; to keep grades manageable required the line initially heading due west through the rugged La Plata Mountains; the first 5 miles to Porter were completed on December 1, 1890.

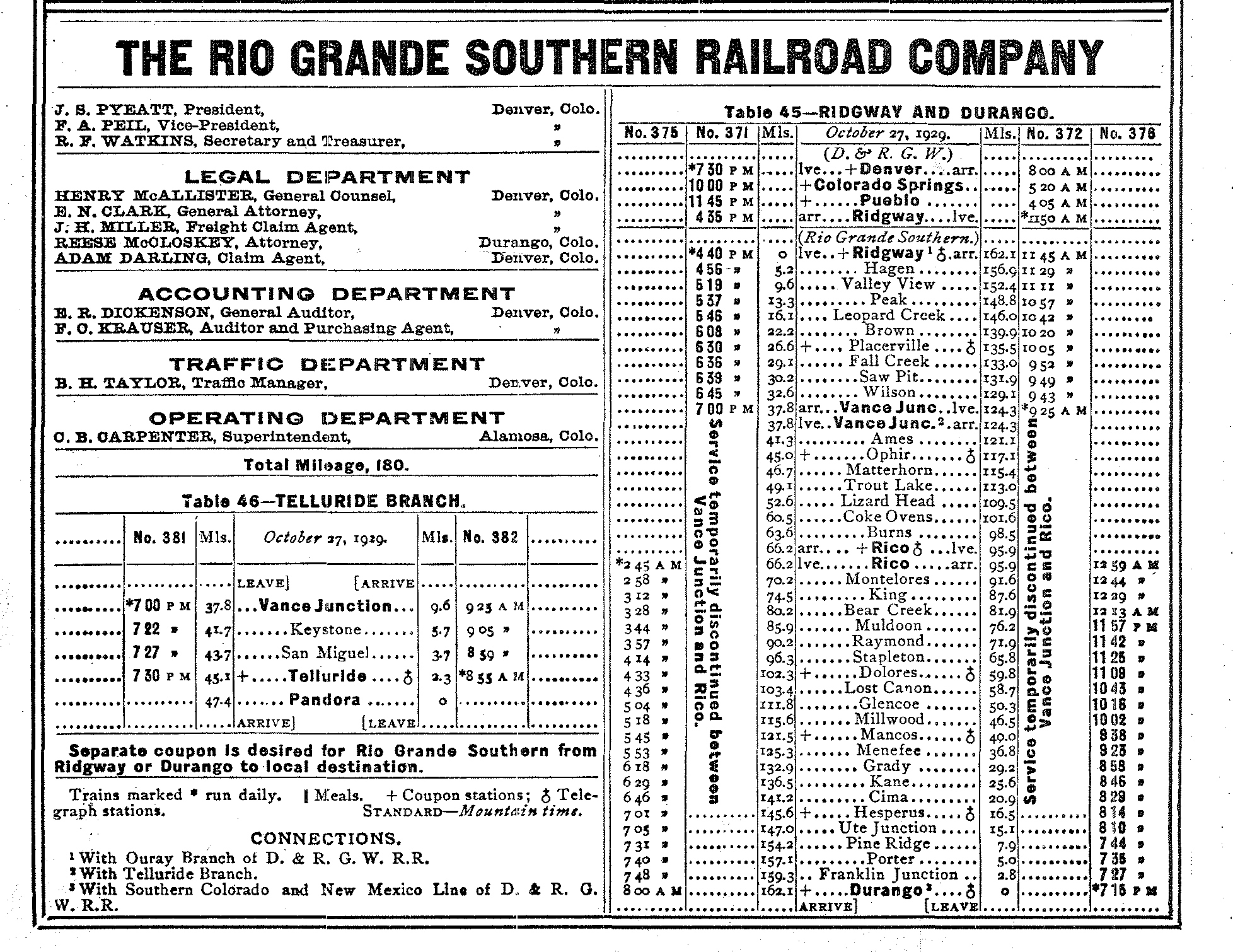

Timetables (1930)

The route then turned north near Dolores before summiting at Lizard Head Pass, 10,250 feet above sea level. In addition, the RGS boasted lower, but similarly difficult summits at Millwood Pass and Cima Pass.

The two crews met at Red Rock, about halfway between Rico and Delores on December 19, 1891. The first through train ran the entire 162 miles from Durango to Ridgway on January 2, 1892. The railroad had cost a total of $9 million to construct.

Mears took control of the road from contractors the following month. To commemorate that occasion he issued 100 sterling silver passes to friends and business associates.

Despite a dog-leg main line filled with tight curves and steep grades, and a routing that required nearly three-times the distance of a corridor through Uncompahgre Canyon, the Rio Grande Southern initially boomed with business.

The railroad was so busy, in fact, that trains creaked and groaned over the rickety 30-pound rail and upgrades were in order to sustain the traffic. If the silver business had continued to flourish the RGS would no doubt have not not only built extensions but also carried out significant improvements.

Proposed Extensions

To handled the strong business, the railroad upgraded the 29-mile segment between Vance Junction and Rico with 57-pound rail. Mears also seriously considered two notable extensions:

- A branch from either Dolores or Mancos into southwestern Utah to serve a gold mine along the San Juan River.

- An even more ambitious project would have extended from Mancos to Prescott Junction (Seligman, Arizona) and established interchange with the Santa Fe's transcontinental main line.

Bankruptcy

On June 30, 1893 the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was repealed, ending not only these ambitious plans but also the Rio Grande Southern's prosperity. The company entered voluntary receivership on August 2, 1893 and Otto Mears lost control of his railroad.

The RGS was subsequently floated a $169,839.10 loan from the Denver & Rio Grande to continue operations. In addition, the D&RG endorsed RGS notes at the sum of $573,498.25.

The result was the RGS becoming a fully controlled subsidiary of the D&RG, which owned about 70% of its common stock. However, the Rio Grande Southern remained a largely independent system and its receivership ended on December 1, 1895.

20th Century Operations

With the lucrative silver trade's collapse, the RGS subsisted on a variety of other business including zinc, gold, lead, other ores, lumber, coal, livestock, and various less-than-carload traffic.

It did relatively well through World War I, during which time the line became a popular tourist attraction thanks to its incredible scenery, earning it the slogan as the "Silver San Juan Scenic Line." Its notable locations included all three passes and Ophir Loop with its high wooden trestles.

In all, the RGS totaled 3,800 feet of wooden trestles ranging in size from 25-75 feet in length. The stiff grades, of course, made the line very difficult to operate, especially in the winter months when snow was so deep and compacted that a rotary plow was sometimes unable to clear the line.

Divisions

During the warmer months rock/mud slides and a waterlogged right-of-way became constant headaches. The RGS maintained three divisions with the road's headquarters, and only roundhouse, located in Ridgway.

- Southern Division: With its headquarters based in Durango, this segment covered 60 miles to Dolores and was situated entirely within the La Plata Mountains

- Middle Division: This section covered 65 miles between Dolores and Vance Junction, linking the Northern and Southern Divisions. This was the railroad's most difficult stretch from an operational standpoint. After following the San Miguel and Dolores Rivers, which often left their banks, it was faced with the rugged San Miguel Mountains. The Middle Division was rife with flooding, heavy snows, sharp curves (including a 24 degree bend near Trout Lake), and steep grades. The line also included Ophir Loop. According to William Moedinger, Jr.'s article "Silver San Juan Scenic Line" from the February, 1942 issue of Trains Magazine, it was sometimes nearly impossible to keep open.

- Northern Division: This section ran from Vance Junction to Ridgway, 37 miles, and also included the 10-mile Telluride Branch, the railroad's only notable spur. It passed through both the San Miguel and Uncompahgre Mountains, featuring the steepest grade on the main line, a 4% climb along the eastern slope of the Uncompahgres.

Rio Grande Southern 2-8-2 #461 and Rio Grande 2-8-2 #452 at the shops in Ridgway, Colorado in the summer of 1950. In the background can be seen the RGS roundhouse. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande Southern 2-8-2 #461 and Rio Grande 2-8-2 #452 at the shops in Ridgway, Colorado in the summer of 1950. In the background can be seen the RGS roundhouse. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Service

By the time operations settled into their typical role after the 1895 reorganization, the Rio Grande Southern generally operated six passenger trains daily over the main line with two trips each day over the Telluride Branch.

The six trips on the main line constituted one daily run in each direction, along each division. In 1907, the RGS typically handled 353 passengers daily, who rode an average of 42 miles.

Before typical passenger trains were retired, the usual train included a 4-6-0 ten-wheeler powering one wooden baggage-mail-express car and a pair of open-platform coaches.

Steam Roster (All-Time)

| Road Number | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built | Construction Number | Cylinders | Drivers | Heritage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1st) | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5672 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #242. | Acquired by the RGS on July 28, 1890. Scrapped in 1904. |

| 1 (2nd)/35 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5200 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #80 ("Chico"). | Became Denver & Rio Grande Western #80 on July 12, 1886, then Rio Grande Western #80. Acquired by the RGS in 1891 as #35. Sold to Boston Coal & Fuel Company as #1. Dismantled in 1913. |

| 2 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5945 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #256. | Acquired by the RGS on August 15, 1890. Scrapped in 1916. |

| 3 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5670 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #243 ("Coxo"). | Acquired by the RGS on March 7, 1891. Retired in the 1920s; dismantled in 1942. |

| 4 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5693 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #244 ("Rico"). | Acquired by the RGS on December 13, 1890. Wrecked in 1901; dismantled in June, 1903. |

| 5 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5689 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #245 ("Frying Pan"). | Acquired by the RGS on May 12, 1891. Dismantled 1904. |

| 6 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5771 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #246 ("Otterbees"). | Acquired by the RGS on April 16, 1891. Returned to the D&RGW on September 24, 1938. Scrapped on October 1, 1938. |

| 7 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5772 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #247 ("Pawnee"). | Leased to the Rio Grande Western from November 28, 1890-January 31, 1891. Acquired by the RGS on April 19, 1891. Dismantled in 1904. |

| 8 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5801 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #248 ("Comanche"). | Acquired by RGS on April 19, 1891. Dismantled in 1904. |

| 9 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5800 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #249. | Acquired by RGS on April 16, 1891. Dismantled in 1904. |

| 10 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5895 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #250. | Acquired by RGS on April 9, 1891. Retired in the 1920s and dismantled in 1942. |

| 11 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin | 1878 | 4336 | 12" x 16" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #29 ("Cochetope"). | Acquired by RGS on January 2, 1891. Sold to George M. Dilley & Sons in 1899. |

| 12 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5896 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #251. | Acquired by RGS on August 1, 1891. Retired in the 1920s and dismantled in 1942. |

| 13 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5917 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #252. | Acquired by RGS on August 1, 1891. Dismantled in 1942. |

| 14 | 0-6-0T | Baldwin | 1881 | 5737 | 14" x 16" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #105. | Acquired by RGS on August 14, 1891. Sold to Yellow Pine Lumber Company (Mobile, AL) in November, 1899. |

| 15 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5919 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #253. | Leased by Rio Grande Western from July 29, 1889-February 1, 1890. Acquired by RGS on December 11, 1891. Retried during the 1920s and dismantled in 1942. |

| 16 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5923 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #254. | Acquired by RGS on December 23, 1891. Retried during the 1920s and dismantled in 1942. |

| 17 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5924 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #255. | Acquired by RGS in November, 1891. Retried during the 1920s and dismantled in 1942. |

| 18 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5957 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #258. | Acquired by RGS on October 26, 1891. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 19 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5956 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #259. | Acquired by RGS on December 22, 1891. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 20 (1st) | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5967 | 15" x 20" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #260. | Acquired by RGS on October 2, 1891. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 20 (2nd) | 4-6-0 | Schenectady | 1899 | 5007 | 16" x 20" | 42" | Built as Florence & Cripple Creek #20 ("Portland"). | Acquired by RGS in January, 1916. Sold to the Rocky Mountain Railroad Club in 1952. Preserved at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden. |

| 21 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5968 | 15" x 20" | 42" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #261. | Acquired by RGS in November 1891. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 22 (1st) | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5954 | 14" x 20" | 45" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #158. | Became Rio Grande Western #20. Acquired by RGS on April 1, 1892. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 22 (2nd) | 4-6-0 | Schenectady | 1900 | 5421 | 16" x 20" | 42" | Built as Florence & Cripple Creek #24 ("Last Dollar"). | Acquired by RGS in January, 1916. Retired in 1942. Dismantled in 1946. |

| 23 | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5960 | 14" x 20" | 45" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #159. Became Rio Grande Western #21. | Acquired by RGS on April 1, 1892. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 24 | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 1882 | 5977 | 14" x 20" | 45" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #165. Became Rio Grande Western #22. | Acquired by RGS on April 1, 1892. Sold to Jonas S. Rice and William M. Rice in September, 1900 who operated a sawmill at Hyatt, Texas. |

| 25 (1st) | 4-6-0 | New York Locomotive Works | 1884 | 90 | 14" x 20" | - | Built as Denver Circle Railroad #7. Became Rio Grande Western #31. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Dismantled in 1916. |

| 25 (2nd) | 4-6-0 | Schenectady | 1899 | 5008 | 16" x 20" | 42" | Built as Florence & Cripple Creek #21 ("Isabella"). | Acquired by RGS in January, 1916. Dismantled in 1940. Tender reused on second #20. |

| 27 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5136 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #71 ("Pacific Slope"). Became Rio Grande Western #71. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to Carolina & Northwestern (#230) on September 27, 1899. |

| 28 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5137 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #71 ("Piedra"). Became Rio Grande Western #72. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to Morenci Southern (#10) in 1900. |

| 29 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5138 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #73 ("Sneffels"). Became Rio Grande Western #73. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to Morenci Southern in 1900. |

| 30 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5164 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #74 ("Hermano"). Became Rio Grande Western #74. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to back to the RGW in 1899. |

| 31 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5184 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #76 ("U.S. Mountain"). Became Rio Grande Western #76. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to Morenci Southern (#11) in 1900. |

| 32 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5185 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #77 ("Rinconida"). Became Rio Grande Western #77. | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Transferred to Silverton, Gladstone & Northerly Railroad (SG&N) in 1899. Dismantled in 1910. |

| 33 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5225 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #78 ("Sandia"). | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Sold to George M. Dilley & Son in 1899. Returned in 1901 and transferred to SG&N in 1902. Dismantled in 1903. |

| 34 (1st) | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5226 | 15" x 18" | 36" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #79 ("La Plata"). | Acquired by RGS in 1891. Traded to Silverton Railroad in 1892 for Shay #34. |

| 34 (2nd) | Shay | Lima | 1890 | 269 | 10" x 12" (3) | 29 1/2" | Built as Silverton Railroad #269 to operate the Red Mountain switchbacks. | Acquired by RGS in 1892 by trading 2-8-0 #34 to the Silverton Railroad. Sold to Siskiwit & Iron River Railway on July 7, 1899 (Ashland Lumber Company) in Ashland, Wisconsin. |

| 36 | 4-4-0 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5119 | 12" x 18" | 45" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #93 ("Roaring Fork"). | Acquired by RGS on December 2, 1891. Sold to the Arkansas Lumber Company (Lester, Arkansas). |

| 40 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5756 | 16" x 20" | 37" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #402 ("Quartz Creek"). | Acquired by RGS in November, 1916. Dismantled in 1943. |

| 41 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1881 | 5731 | 16" x 20" | 37" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #409 ("Red Cliff", later "Red Buttes"). | Acquired by RGS in November, 1916. Sold to Knott's Berry Farm in November, 1951 (Buena Park, California). |

| 42 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1887 | 8626 | 16" x 20" | 37" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande #420. | Acquired by RGS in November, 1916. Sold to the Narrow Gauge Motel in Alamosa, Colorado in 1953. |

| 74 | 2-8-0 | Brooks | 1898 | 2951 | 16" x 20" | 37" | Built as Colorado & Northwestern #30. Was later Denver, Boulder & Western #30 and Colorado & Southern #74 (1921) before becoming Morse Brothers Machinery & Supply (1945). | Acquired by RGS in November, 1948. Sold to the City of Boulder, Colorado in 1952. |

| 455 | 2-8-2 | Baldwin | 1903 | 21832 | 17" x 22" | 40" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande Western #455 (Class K-27 "Mudhen") | Acquired by RGS by trading maintenance-of-way ditcher #030. Wrecked in November, 1943; rebuilt in 1947; scrapped in 1953. |

| 461 | 2-8-2 | Baldwin | 1903 | 21729 | 17" x 22" | 40" | Built as Denver & Rio Grande Western #461 (Class K-27 "Mudhen") | Acquired by RGS on September 30, 1950. Dismantled in 1953. |

The Rio Grande Southern carries the fascinating distinction of never having purchased a steam locomotive new. By the time the road was constructed in the 1890s, narrow-gauge fever had largely ended. As a result, Otto Mears purchased all of his original 35 locomotives, consisting of 2-8-0's, 2-6-0's, 4-4-0's, and a single Shay second-hand. Most were former D&RG units.

Rio Grande Southern business car "Edna" (B-20), along with a group of gondolas and two cabooses, layover near the water tank at the end of the Telluride Branch in Telluride, Colorado in 1951. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande Southern business car "Edna" (B-20), along with a group of gondolas and two cabooses, layover near the water tank at the end of the Telluride Branch in Telluride, Colorado in 1951. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.Final Years

Miller was replaced by Cass M. Herrington as receiver on November 16, 1938. The new director did his best to keep the road going by securing low-interest Reconstruction Finance Corporation loans whenever possible.

As George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the Rio Grande Southern would probably have folded prior to 1941 if not for a surge in wartime traffic. In particular, the government purchased large quantities of uranium-laced ores produced in the region, which helped build the United States' first atomic bomb.

Unfortunately, struggles continued after the war and remaining customers slowly switched to trucking as highways improved. In 1948, J. Pierpont Fuller replaced Herrington as receiver, at which point little time remained for the railroad.

In January, 1949 a boiler explosion on the road's only rotary forced the closure of the line over Lizard Head Pass during the winter months. The mail contracts were lost, officially, on March 31, 1950 when the Post Office canceled its involvement with the RGS due to declining service.

Interestingly, both mail and passenger business had actually ceased months earlier on December 18, 1949 due to the on-setting winter weather. However, excursion trains continued to run through 1950 and 1951 when weather permitted.

The final blow came with the loss of the Idarado Mining Company business at Pandora on June 1, 1951, and the Rico-Argentine Mine later that year. These two shippers accounted for most of the railroad's remaining business. With a future that appeared hopeless, permission was requested to suspend operations on December 17, 1951.

This was granted, along with Interstate Commerce Commission permission to abandon all operations, which officially occurred on April 15, 1952. Interestingly, little time was wasted on pulling up the tracks which took place later that same year in September.

Postscript

Even if the Rio Grande Southern could have continued beyond 1951-1952 the road would not have survived much longer. It was destitute and, according to Robert Richardson's article entitled, "Rio Grande Southern Calls It Quits," from the June, 1952 issue of Trains Magazine, the company owed the RFC more than $50,000 in unpaid wartime loans.

In addition, it had incurred nearly $1 million in deficits and also owed $700,000 in unpaid local and federal taxes. Despite its many struggles the RGS was a fascinating operation featuring some of the most stunning natural vistas available anywhere in the country by rail.

If the railroad could have somehow survived as a popular tourist attraction into the modern era it would certainly rival any of the most popular today, such as the Durango & Silverton Narrow-Gauge and Strasburg Railroads.

More Reading

Sources

- Hilton, George. American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

- Moedinger, Jr. William. "Silver San Juan Scenic Line." Trains Magazine. Volume #2, Issue #4. February, 1942. Pages 8-25.

- Morgan, David P. "Business Cars At Lizard Head." Trains Magazine. Volume #19, Issue #4. February, 1959. Pages 16-17.

- Ferrell, Mallory Hope. Silver San Juan, The Rio Grande Southern Railroad (First Edition). Boulder: Pruett Publishing Company, 1973.

- Richardson, Robert W. "Rio Grande Southern Calls It Quits." Trains Magazine. Volume #12, Issue #8. June, 1952. Pages 14-15.

- Zimmermann, Karl. "Guest Goose." Trains Magazine. Volume #60, Issue #3. March, 2000. Pages 56-57.

Recent Articles

-

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase. -

CSX Advances Locomotive Technology to Cut Fuel Use and Emissions

Feb 19, 26 09:43 AM

CSX recently highlighted major progress on its ongoing efforts to reduce fuel consumption, cut greenhouse-gas emissions, and improve operational efficiency across its freight rail network through adva… -

Ohio Railway Museum Unveils “Vision for the Future” Plan

Feb 19, 26 09:39 AM

The Ohio Railway Museum (ORM), one of the nation’s oldest all-volunteer rail preservation organizations, has laid out an ambitious blueprint aimed at transforming its organization. -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils $38M Expansion

Feb 19, 26 09:24 AM

Western Maryland Railway F7 236 points towards the Mount Clare Roundhouse in Baltimore as part of the B&O Museum. -

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic To Repower Two FPA4s

Feb 19, 26 09:21 AM

A pair of classic, streamlined Alco/MLW FPA4 locomotives that have become signature power on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) are slated for a major mechanical transformation. -

Ohio's Dinner Train Rides At The CVSR

Feb 19, 26 09:18 AM

While the railroad is well known for daytime sightseeing and seasonal events, one of its most memorable offerings is its evening dining program—an experience that blends vintage passenger-car ambience… -

Indiana Dinner Train Rides In Jasper

Feb 19, 26 09:16 AM

In the rolling hills of southern Indiana, the Spirit of Jasper offers one of those rare attractions that feels equal parts throwback and treat-yourself night out: a classic excursion train paired with… -

New Hampshire Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:12 AM

The state's murder mystery trains stand out as a captivating blend of theatrical drama, exquisite dining, and scenic rail travel. -

New York Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:07 AM

New York State, renowned for its vibrant cities and verdant countryside, offers a plethora of activities for locals and tourists alike, including murder mystery train rides! -

UP, NS Set April 30 Date To Refile Merger Application

Feb 18, 26 04:36 PM

Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern have told federal regulators they will submit a revised merger application on April 30, restarting the formal review process for what would become one of the most co… -

CTDOT May Swap Shore Line East’s Electrics For Diesels

Feb 18, 26 04:20 PM

Connecticut’s Shore Line East (SLE) commuter rail service—one of the state’s most scenic and strategically important passenger corridors—could soon see a major operational change. -

NPS Awards $1.93M To Sioux City Railroad Museum

Feb 18, 26 01:21 PM

The Sioux City Railroad Museum has received a $1.93 million National Park Service grant aimed at pushing the museum’s long recovery from the June 2024 flooding. -

$1.3M Mott Foundation Grant To Help Rebuild Rio Grande 2-8-2 No. 464

Feb 18, 26 09:43 AM

A $1.3 million grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation will fund critical work on steam locomotive No. 464, the railroad’s 1903-built 2-8-2 “Mikado” that has been out of service awaiting heavy… -

NS Unveils Third “Landmark Series” Locomotive

Feb 18, 26 09:38 AM

Norfolk Southern has officially introduced ES44AC No. 8184, the third locomotive in its new “Landmark Series,” a program that spotlights the historic rail cities and communities that helped shape both… -

WMSR's Georges Creek Division: Reviving A Long-Dormant Line

Feb 18, 26 09:34 AM

In 2024 the WMSR announced it was rebuilding part of the old WM. The Georges Creek Division will provide both heritage passenger service and future freight potential in a region once defined by coal… -

Chesapeake & Ohio 614 Restoration Pushes Forward

Feb 18, 26 09:32 AM

One of the most recognizable mainline steam locomotives to survive the post–steam era, C&O 614, is steadily moving through an intensive return-to-service overhaul. -

Montana Dinner Train Rides Near Lewistown

Feb 18, 26 09:30 AM

The Charlie Russell Chew Choo turns an ordinary rail trip into an evening event: scenery, storytelling, live entertainment, and a hearty dinner served as the train rumbles across trestles and into a t… -

Wisconsin Dinner Train Rides In North Freedom

Feb 18, 26 09:18 AM

Featured here is a practical guide to Mid-Continent’s dining train concept—what the experience is like, the kinds of menus the museum has offered, and what to expect when you book. -

Pennsylvania Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:09 AM

Pennsylvania, steeped in history and industrial heritage, offers a prime setting for a unique blend of dining and drama: the murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Jersey Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 18, 26 09:06 AM

There are currently no murder mystery dinner trains available in New Jersey although until 2023 the Cape May Seashore Lines offered this event. Perhaps they will again soon! -

Huckleberry Railroad: Riding Narrow-Gauge Steam In Michigan!

Feb 18, 26 09:03 AM

The Huckleberry Railroad is a tourist attraction that is part of the Crossroads Village & Huckleberry Railroad Park located in Flint, Michigan featuring several operating steam locomotives. -

New York & Lake Erie Unveils M636 No. 636 In New Colors (2025)

Feb 17, 26 02:05 PM

In mid-May 2025, railfans along the former Erie rails in Western New York were treated to a sight that feels increasingly rare in North American railroading: a big M636 in new paint. -

First Siemens “Northlander” Trainset Arrives In Ontario

Feb 17, 26 11:46 AM

Ontario’s long-awaited return of the Northlander passenger train took a major step forward this winter with the arrival of the first brand-new Siemens-built trainset in the province. -

Sound Transit Set to Launch Cross-Lake Service

Feb 17, 26 10:09 AM

For the first time in the region’s modern transit era, Sound Transit light rail trains will soon carry passengers directly across Lake Washington -

Michigan’s Old Road Dinner Train Still Seeks New Home

Feb 17, 26 10:04 AM

In May, 2025 it was announced that Michigan's Old Road Dinner Train was seeking a new home to continue operations. As of this writing that search continues. -

WMSR Acquires Conemaugh & Black Lick SW7 No. 111

Feb 17, 26 10:00 AM

In a notable late-summer preservation move, the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) announced in August 2025 that it had acquired former Conemaugh & Black Lick Railroad (C&BL) EMD SW7 No. 111. -

MBTA Unveils New Haven-Inspired Locomotive

Feb 17, 26 09:58 AM

he Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority has pulled back the curtain on its newest heritage locomotive, F40PH-3C No. 1071, wearing a bold, New Haven–inspired paint scheme that pays tribute to the… -

Missouri Dinner Train Rides In Branson

Feb 17, 26 09:53 AM

Nestled in the heart of the Ozarks, the Branson Scenic Railway offers one of the most distinctive rail experiences in the Midwest—pairing classic passenger railroading with sweeping mountain scenery a… -

Texas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:49 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 17, 26 09:48 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

RTA To Become The Northern Illinois Transit Authority

Feb 16, 26 12:49 PM

Later this year, the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)—the umbrella agency that plans and funds public transportation across the Chicago region—will be reorganized into a new entity: the Norther… -

CPKC Holiday Train Sets New Record In 2025

Feb 16, 26 11:06 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City’s (CPKC) beloved Holiday Train wrapped up its 2025 tour with a milestone that underscores just how powerful a community tradition can become. -

Historic Izaak Walton Inn Slated To Close

Feb 16, 26 10:51 AM

A storied rail-side landmark in northwest Montana—the Izaak Walton Inn in Essex—appears headed for an abrupt shutdown, with employees reportedly told their work will end “on or about March 6, 2026.” -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils Restored American Freedom Train No. 1

Feb 16, 26 10:31 AM

The B&O Railroad Museum has completed a comprehensive cosmetic restoration of American Freedom Train No. 1, the patriotic 4-8-4 steam locomotive that helped pull the famed American Freedom Train durin…