South Carolina Canal & Rail Road Company: Map and History

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, also sometimes regarded as the Charleston & Hamburg, was an early railroad established just a few months after the charter of the first common-carrier, the Baltimore & Ohio.

The SCC&RR was an audacious project which looked to connect the major port city of Charleston to inland regions of the Palmetto State, notably its centralized agricultural sector.

The success of the railroad was also thanks to a visionary chief engineer who recognized the importance of the steam locomotive in the movement of people and goods.

Historically, the Charleston & Hamburg is best recognized for being the first to operate a regularly scheduled passenger train pulled by a steam locomotive during late 1830.

After less than two decades of service the SCC&RR disappeared through merger. What remained of it became part of the famous Southern Railway although today little of the original right-of-way remains.

A view of a "Best Friend" replica at the Best Friend of Charleston Museum in Charleston, South Carolina.

A view of a "Best Friend" replica at the Best Friend of Charleston Museum in Charleston, South Carolina.History

By the mid-1820s the concept of railroads was gaining serious headway in the relatively new United States of America.

With the development of the steam locomotive by Richard Trevithick of England who showcased his new invention on February 21, 1804, it was clear that railroads could play a vital role in the faster movement of people and goods.

Some small incline railways and local horse-drawn operations were in service in the Northeast although it was not until the B&O was chartered and organized on April 24th, 1827 was the first, true common-carrier line established in the country.

The B&O was created by Baltimore businessman who wanted to make sure that their city remained a vital port and did not want to be outdone by the newfangled canal systems.

Incorporation

Other east coast cities took notice and the port of Charleston, South Carolina followed suit on December 19, 1827 establishing the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company.

The purpose of the company was to haul agricultural products from inland farms, notably the important cotton crop, to the port city for shipment.

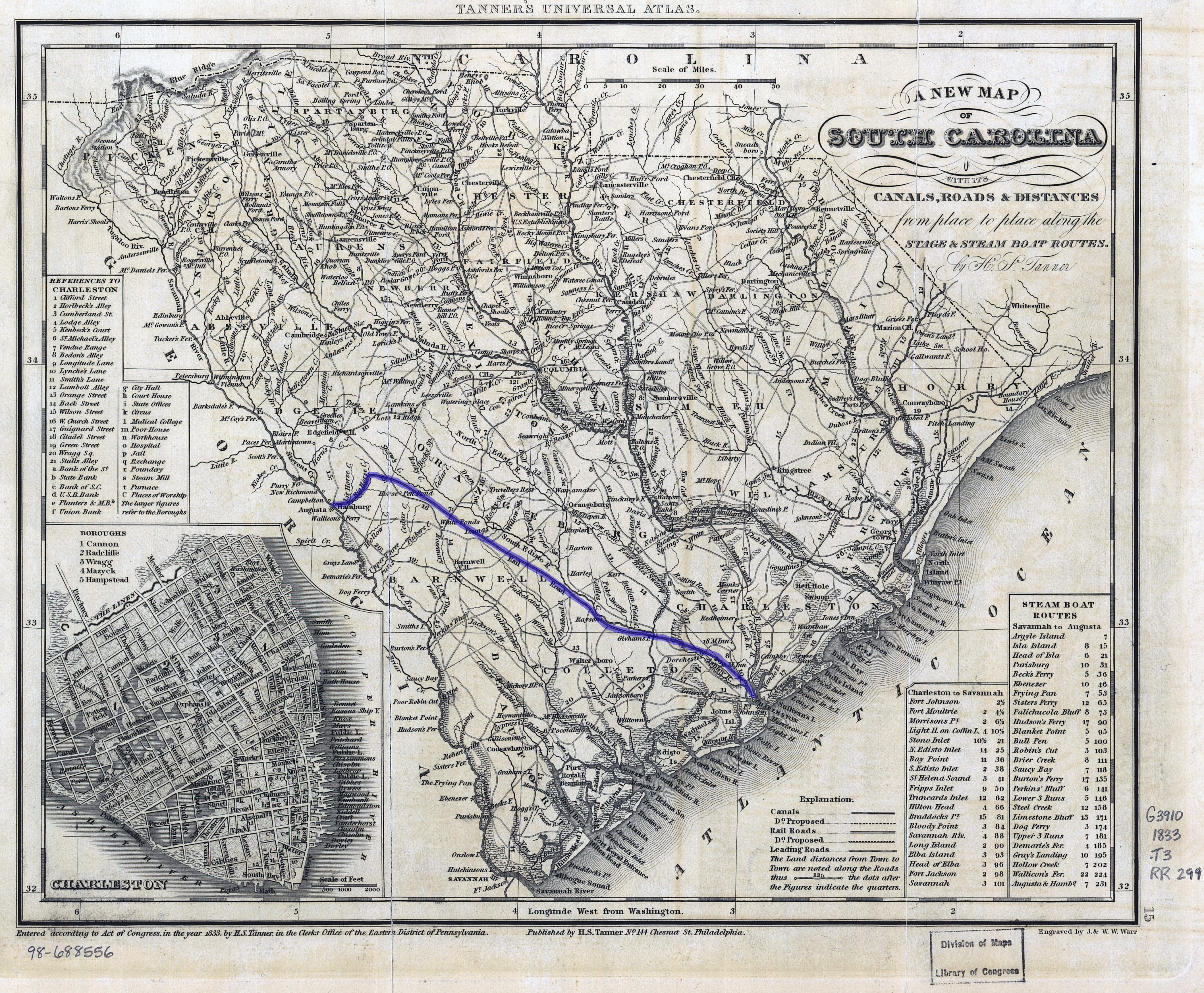

The hope was to connect Hamburg, Columbia, Augusta (Hamburg), and Camden to the west along a route nearly 140 miles in length with a canal spanning the gap between the Savannah and Ashley rivers (hence the "canal" in the name).

Just as with Baltimore, Charleston feared that if it did not take the risk of building a railroad it may wither and be left out in the cold while other east coast ports gained an edge.

The most pertinent reason for this anxiety was the new canal systems that had been proposed, particularly in the northeast and New York City was already connected via the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company.

At A Glance

While the railroad was unproven, Charleston business leaders felt they had no choice but to attempt the project, and quite a project it was.

By the summer of 1830 the SCC&RR had 6 miles of track in service west of its terminal and yard in Charleston, the Camden Depot (now a National Historic Landmark).

The railroad's chief engineer, Horatio Allen, had been to England to test steam locomotives, as well as operate the Stourbridge Lion design being tested on the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company in 1829 (officially, the first such locomotive ever operated in the U.S. but was built in England).

Allen had left the D&H due to its unwillingness to embrace steam power which the young engineer felt was the future of transportation. SCC&RR, as well as Charleston officials, bought into his beliefs and the railroad received its first locomotive in October, 1830 built by the West Point Foundry of Cold Spring, New York (near the NYC).

System Map (1833)

It was christened as the Best Friend of Charleston due to the area it served and was first operated by Allen on Christmas Day, 1830 becoming the first steam locomotive to pull a regularly scheduled passenger train in the United States.

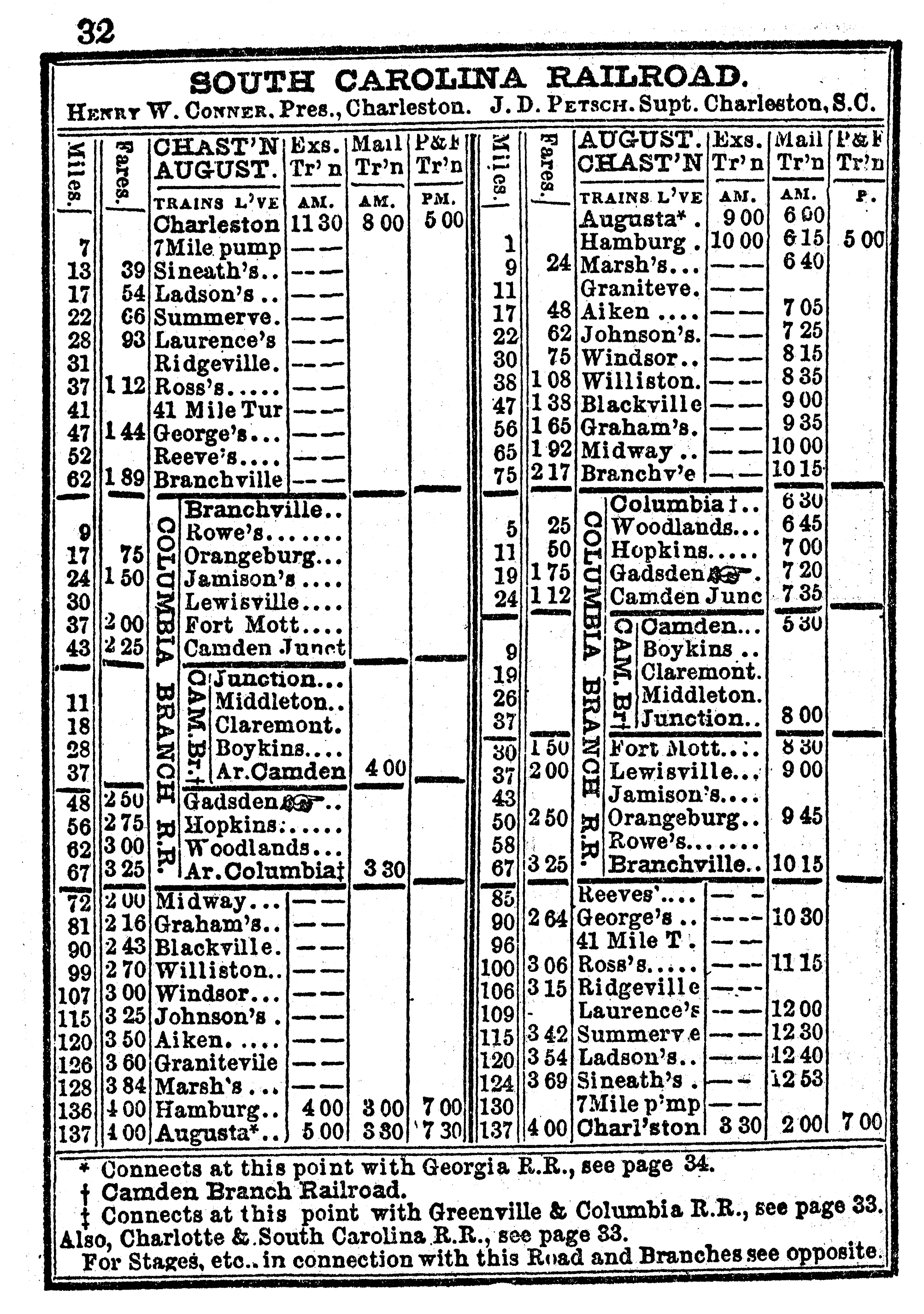

Soon after the SCCRR first 6 miles were opened work quickly commenced on rest of the route. By October, 1833 the entire 136-mile route between Charleston and Hamburg (directly across the Savannah River from Augusta) was open.

It required the work of more than 1,300 contractors and a price tag of $950,000. The route was constructed mostly using strap-iron tracks (literally iron straps bolted to a wooden timbers) that were placed above wooden sills.

Best Friend Of Charleston (Locomotive)

However, this quickly proved impractical. Despite Allen's reputation as an early expert on railroad technology, Dr. George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," his theory of wooden trestle-work in place of standard fill proved a disaster.

The wood quickly deteriorated in the intense southern heat and humidity which led to numerous derailments. Between 1833 and 1839, the SCC&RR spent an additional $463,000 to replace this design with traditional earthen embankments and modern "T"-rail.

When the Charleston & Hamburg was opened it was easily not only the longest railroad in the United States but also the world.

All other lines in use at the time were no more than a few dozen miles in length, as the B&O for instance was only operating about 13 miles of railroad at that point in time.

Two years after opening its entire main line the SCC&RR owned 23 locomotives by 1835. Unfortunately, the line expanded little after completing its initial route save for a branch it built to the capital of Columbia.

Merger

While it was profitable it never moved the hundreds of thousands of cotton bushels and other agriculture its builders had intended.

Additionally, it ran into stiff competition with steam boats operating on the Savannah River and Augusta as upset that the railroad never reached across the waterway to directly serve the city (due to this the city chartered several of its own railroads and it became a major hub of rail commerce).

Ironically, Hamburg never even truly embraced the SCCRR. In early 1844 the system merged with the Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston to form the South Carolina Railroad Company.

The system was later reorganized as the South Carolina Railroad in 1881 after it could not recover from the devastation suffered during the Civil War.

Under its latest name the railroad expanded through the Carolinas but again fell into receivership in 1894, emerging as the South Carolina & Georgia Railroad.

By 1899 the SC&G was acquired by the Southern Railway and became part of its Piedmont Division. Today, little of the original SC&RR right-of-way remains in use although the roadbed can still be easily seen in several locations, even through towns that sprang up along the line if one knows were to look.

Also, the city of Charleston has many markers showcasing where the original tracks were located (and where the Best Friend was operated) as well as the aforementioned Camden Depot.

Recent Articles

-

Tennessee's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 11:42 PM

If you’re looking for a Chattanooga outing that feels equal parts special occasion and time-travel, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) has a surprisingly elegant answer: The Homefront Tea Roo… -

Kentucky's Tea Tasting Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 11:36 PM

A seasonal favorite of the My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is their “Princess Tea Party,” a whimsical excursion that blends the nostalgia of vintage rail travel with a magical, fairy-tale experience for… -

Maryland Easter Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 10:54 PM

Maryland is where it all began with railroads as the state was home to the first common-carrier. Today, three different organizations host Easter-themed train rides. -

Connecticut Easter Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 10:38 PM

While spring arrives late in New England, there are scenic train rides available each March or April that celebrate the Easter holiday. -

Arizona Easter Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 10:32 PM

Surprisingly one location in Arizona plays host to a Easter-themed event for the entire family, the Verde Canyon Railroad. -

Ohio BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 13, 26 12:27 PM

Among the HVSR's most popular special events is the “Starbrick BBQ Ribs and Wings Dinner Train,” a culinary-themed excursion that combines classic barbecue cuisine with a relaxing evening rail journey… -

Maryland Dinner Train Rides At Walkersville

Mar 13, 26 11:47 AM

While WSRR runs a variety of seasonal and special trains, one of its most appealing “date night” offerings is the Valentine’s Dinner Train, a romantic two-hour ride built around classic railroad ambia… -

Arkansas Dinner Train Rides On The A&M

Mar 13, 26 11:35 AM

If you want a railroad experience that feels equal parts “working short line” and “time machine,” the Arkansas & Missouri Railroad delivers in a way few modern operations can. -

North Carolina Dinner Train Rides At Spencer

Mar 13, 26 10:01 AM

Tucked into the Piedmont town of Spencer, the North Carolina Transportation Museum is the kind of place that feels less like a typical museum and more like a living rail yard that never quite stopped… -

Tennessee Dinner Train Rides At TVRM

Mar 13, 26 09:56 AM

Tucked into East Chattanooga, the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum (TVRM) is less a “museum you walk through” and more a railroad you step aboard. -

New York Dinner Train Rides In The Adirondacks

Mar 13, 26 09:36 AM

Operating over a restored segment of the former New York Central’s Adirondack Division, the Adirondack Railroad has steadily rebuilt both track and public interest in passenger rail across the region. -

Pennsylvania Dinner Train Rides At Boyertown

Mar 13, 26 09:33 AM

With beautifully restored vintage equipment, carefully curated menus, and theatrical storytelling woven into each trip, the Colebrookdale Railroad offers far more than a simple meal on rails. -

Wisconsin BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:57 PM

The Wisconsin Great Northern Railroad will once again welcome passengers aboard its popular Spring BBQ Dinner Train in 2026. -

Connecticut DOT Awards $20 Million In Railroad Grants

Mar 12, 26 01:19 PM

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) has announced a new round of funding aimed at improving the safety, reliability, and capacity of the state’s freight rail network. -

California's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 12:59 PM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Reading & Northern Unveils Semiquincentennial 1776

Mar 12, 26 12:48 PM

In November 2025, the Reading, Blue Mountain & Northern Railroad (RBMN)—commonly known as the Reading & Northern—announced the debut of a striking patriotic locomotive commemorating the upcoming 250th… -

New Jersey's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:35 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Florida BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:28 AM

While Florida does not currently offer any BBQ train rides the Florida Railroad Museum does host a similar event, a campfire experience! -

Texas "Murder Mystery" Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:40 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:36 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

Missouri's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:33 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:28 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Charlotte Approves $37.9M For "Red Line" To Lake Norman

Mar 11, 26 02:18 PM

The Charlotte City Council has approved $37.9 million in funding for the next phase of design work on the long-planned Red Line commuter rail project. -

NS, Progress Rail Announce SD70ICC Modernization

Mar 11, 26 12:15 PM

Norfolk Southern Railway has announced a significant locomotive modernization initiative in partnership with Progress Rail Services Corporation that will rebuild 96 existing road locomotives into a ne… -

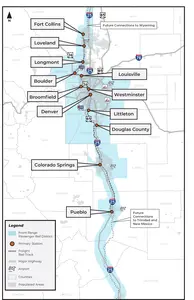

Colorado Seeks Input On Proposed Front Range Passenger Train Name

Mar 11, 26 11:55 AM

Colorado officials are inviting the public to help name a proposed passenger train that could one day connect major cities along the state’s heavily traveled Interstate 25 corridor. -

Virginia Whiskey Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 11:22 AM

Among the Virginia Scenic Railway's most popular specialty excursions is the “Bourbon & BBQ” tasting train, an adults-oriented rail journey that pairs scenic views of the Shenandoah Valley with guided… -

Minnesota's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:32 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train. -

New Mexico's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:23 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Indiana's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:19 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:02 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Kentucky Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 11:39 AM

The Bluegrass State is home to beautiful rolling farms and the western Appalachian Mountain chain, which comes alive each spring. A few railroad museums host Easter-themed events during this time. -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:26 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

NS Faces Multiple Derailments Near Historic Horseshoe Curve

Mar 10, 26 10:15 AM

One of America’s most famous railroad landmarks, the legendary Horseshoe Curve west of Altoona, Pennsylvania, has recently been the site of multiple freight-train derailments involving Norfolk Souther… -

Oregon's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:11 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:57 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Connecticut's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:54 AM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on… -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:37 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Union Pacific Restores Rail Bridge Service in Lincoln

Mar 09, 26 11:34 PM

Union Pacific crews have successfully restored freight rail service across a key bridge in Lincoln, Nebraska, completing a rapid reconstruction effort in just a few weeks. -

TVRM To Assist In Gas-Powered Locomotive's Restoration

Mar 09, 26 11:15 PM

The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum has announced it is assisting in the eventual cosmetic restoration of a former gas powered locomotive used in the logging industry. -

Michigan's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:37 AM

Spring sometimes comes late to Michigan but this doesn't stop a handful of the state's heritage railroads from hosting Easter-themed rides. -

Pennsylvania's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:05 AM

Pennsylvania is home to many tourist trains and several host Easter-themed train rides. Learn more about these special events here. -

Tennessee's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:33 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Michigan's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:07 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:56 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Maryland Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:37 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

New York's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:16 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:15 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Colorado Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:14 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:13 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 1356 Receives Cosmetic Restoration

Mar 07, 26 02:19 PM

A significant preservation effort is underway in Missoula, Montana, where volunteers and local preservationists have begun a cosmetic restoration of Northern Pacific Railway steam locomotive No. 1356.