Southern San Luis Valley Railroad: Route, Roster, History

Last revised: September 11, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Southern San Luis Valley Railroad (SSLV) occupies an interesting niche in the rich tapestry of American railroad history.

This short line played a pivotal role in the development and sustenance of Colorado's San Luis Valley, demonstrating the profound impact of localized rail services on regional growth and economic development.

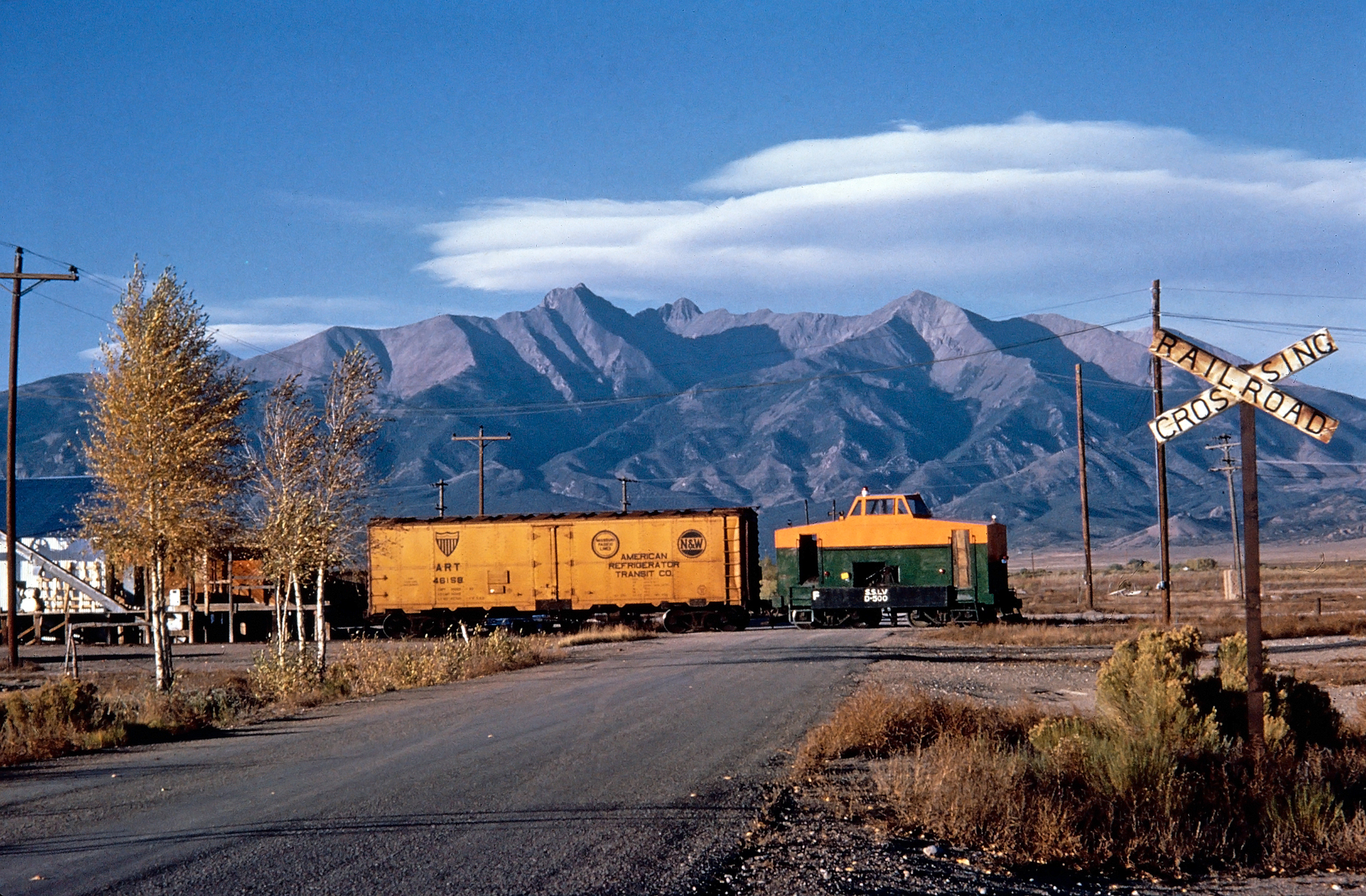

At its peak the SSLV operated 31 miles between a connection with the Rio Grande at Blanca to Jaroso, Colorado. However, the railroad is best remembered for its late era operations where it operated just 1.5 miles of track near Blanca and utilized a custom-built diesel switcher (pictured).

Photos

Southern San Luis Valley's homebuilt diesel critter, D-500, in service at the Rio Grande connection in Blanca, Colorado during the fall of 1973. American-Rails.com collection.

Southern San Luis Valley's homebuilt diesel critter, D-500, in service at the Rio Grande connection in Blanca, Colorado during the fall of 1973. American-Rails.com collection.History

The history of the Southern San Luis Valley begins in the late 19th century, a time when the expansion of the railroad network across the United States was driving economic growth and facilitating the settlement of remote areas.

The San Luis Valley, with its fertile land and potential for agricultural development, attracted attention from investors and settlers alike. However, the valley's geographic isolation posed significant challenges, which the SSLV was established to address.

The system began as the San Luis Southern Railroad, chartered on July 3, 1909, under the auspices of the Costilla Estates Development Company.

This venture aimed to foster agricultural communities through the development of farmland. Envisioned as the lifeline for these small hamlets, the railroad's success hinged on the prosperity of the Costilla Estates, which in turn depended critically on irrigation from its constructed reservoirs.

The original line ran from a connection with the Denver & Rio Grande Western at Blanca, south to rural Jaroso at the New Mexico border. This route was strategic, serving not only the agricultural communities but also tapping into the rich mineral resources found in the surrounding mountains.

Predominantely, however, the railroad relied upon agricultural products such as barley and potatoes - and later, lettuce - from the valley to major markets across the United States.

Alas, nature had other plans for the fledgling railroad. The anticipated rainfall needed to fill these reservoirs proved insufficient, leading to unmet agricultural needs. The ripple effect was a lack of economic viability for both the estates and the railroad, propelling the latter into bankruptcy.

It was on this backdrop that Charles Boettcher, a prominent industrial magnate, stepped in. On January 6, 1928, Boettcher purchased the failing railroad, reinventing it later that year as the San Luis Valley Southern Railway.

Despite this new leadership and reorganization, the railroad continued to face formidable challenges. Under Boettcher's direction, while there were efforts to rejuvenate its operations, the railway struggled to find its stride in the shadow of persistent financial and environmental hurdles.

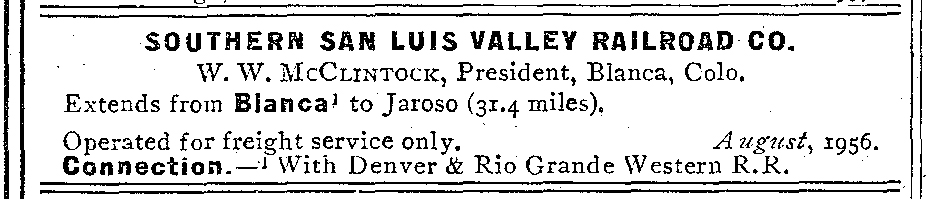

Official Guide Listing (3/1957)

The Southern San Luis Valley's listing in the "Official Guide" just prior to much of the system being sold and abandoned. American-Rails.com collection.

The Southern San Luis Valley's listing in the "Official Guide" just prior to much of the system being sold and abandoned. American-Rails.com collection.There were a number of attempts to abandon the property after World War II. The first occurred on January 24, 1949 when the Boettcher/McLean estates petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to discontinue operations.

This move sparked considerable resistance from local stakeholders in the valley, who saw value and potential in the railway's continued operation.

Amid these intense legal battles, two local businessmen entered into negotiations to acquire the property. Their timely acquisition occurred just two weeks before the scheduled abandonment hearings, marking a pivotal turn in the railroad's history.

From 1949 to 1954, the new owners navigated through a complicated landscape of financial arrangements and strategic maneuvers in an effort to sustain the struggling railway.

Despite their efforts, by September 19, 1952, owner W.W. McClintock found compelled to file for abandonment himself due to sagging traffic. However, the ICC only approved a partial abandonment on September 24, 1953, allowing McClintock to continue operations under constrained conditions.

In a continued effort to revive the company's fortunes, McClintock, along with George Oringdulf, another local businessman, embarked on a comprehensive reorganization.

They consolidated control by acquiring all outstanding stock and effectively tying up any loose ends. This restructuring culminated in the formation of a new entity under the laws of Colorado.

On December 11, 1953, this new venture was officially organized, and on October 22, 1954, it was rebranded as the Southern San Luis Valley Railroad (SSLV).

Motive Power

Over the decades, the railroad's roster has featured an eclectic mix of locomotives, each with its own story and pedigree. It began with #100 and #101, both Brooks 4-6-0s, former Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway. In addition, #102, a 2-6-0 built by Baldwin, was acquired new by the San Luis Southern.

The roster also included a quarter of former Rio Grande 2-8-0s (C-28): #103 (D&RGW 657), #104 (D&RGW 633), #105 (D#RGW 688), and #106 (D&RGW 683).

The railroad also operated a motorcar for passenger service, numbered M-3, built by Winter-Weiss in 1924. It was later renumbered M300 and is preserved but in a state of disrepair at the Oklahoma Railway Museum in Oklahoma City.

The most interesting locomotive, however, was a custom-built diesel critter. In the mid-20th century, McClintock and Oringdulph of grappled with a significant challenge.

Their two steam locomotives, #105 and #106, proved excessively costly to maintain. To reduce operating costs, they acquired the tender from Rio Grande 2-8-0 964 in 1950 and embarked on an ambitious project to fashion a more economical locomotive.

The initial attempt to build on the tender frame did not yield success. However, undeterred, by 1955, their persistence paid off with the completion of a distinctive machine, dubbed the D-500.

This unconventional locomotive was mounted on standard tender trucks, driven by a sprocket and chain drive system. It was powered by a 1091 cubic inch, UD24 diesel engine from International Harvester.

The innovative power transmission involved a Caterpillar hydraulic transmission that drove an old Euclid truck axle. This, in turn, channelled power via sprockets and chains to the axles.

The D-500 boasted an unusual design, resembling more a caboose than a traditional locomotive. It featured a cupola-styled cab, optimizing visibility and facilitating the installation of the primary engine components. The entire assembly was expertly crafted by the SSLV mechanics in Mesita, Colorado.

This inventive project culminated in a significant operational shift for the railroad. By 1957, all steam locomotives had been phased out on the SSLV, marking the end of an era and the beginning of a new chapter in railway ingenuity.

Final Years

Post-war, the SSLV continued to be a lifeline for the San Luis Valley, but like many railroads, it began to face challenges in the 1950s and 1960s from the rise of automobile travel and the construction of interstate highways.

These developments made truck transport increasingly viable and economical, eroding the market share of railroads.

By the late 1950s, the operating scope of the SSLV had significantly contracted. The railroad primarily functioned in a localized area, with its traffic base concentrated near Blanca with minimal south of that point.

On March 15, 1958, the railroad discontinued operations on the southerly 29 miles from McClintock to Jaroso; the tracks were subsequently sold to the Climax Molybdenum Company. This left the SSLV operating a mere 2.5-mile section southward from Blanca.

This truncated segment enabled the SSLV to serve strategic local industries; notably, it facilitated operations for the Colorado Aggregates Company at McClintock and the Mizokami lettuce packing plant, located just north of the McClintock wye.

Alas, the closure of the Mizokami lettuce plant in the late 1970s marked the end of an era. The following sale of the SSLV to the Hecla Mining Company signaled another significant transformation, illustrating the evolving economic landscape in which these rail operations were embedded.

Southern San Luis Valley's homebuilt diesel critter, D-500, at the Rio Grande connection in Blanca, Colorado during the summer of 1973. The locomotive was built from a steam tender frame and utilized an I-H (International Harvester) power plant. American-Rails.com collection.

Southern San Luis Valley's homebuilt diesel critter, D-500, at the Rio Grande connection in Blanca, Colorado during the summer of 1973. The locomotive was built from a steam tender frame and utilized an I-H (International Harvester) power plant. American-Rails.com collection.Legacy

Today, the legacy of the Southern San Luis Valley Railroad is evident in the continued importance of rail transport in the region. Although no longer operating under its original name, the tracks of the SSLV continue to support local industries and remain a critical part of the infrastructure supporting the San Luis Valley’s economy.

In conclusion, the history of the Southern San Luis Valley Railroad is a compelling chapter in the story of American railroads. It highlights the crucial role of small-scale, community-focused rail services in supporting regional economies.

The SSLV may not have the name recognition of larger railroads, but its impact on the communities it served is a testament to the broader significance of railroads in American economic and regional development.

This history serves not only as a record of past achievements but also as a reminder of the potential for specialized transportation solutions to drive economic success in geographically isolated areas.

Of note, former 2-8-0 #106 has been restored to its original D&RGW number and markings, and is proudly displayed at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden.

Recent Articles

-

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:11 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

North Carolina Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:09 AM

The springs are typically warm and balmy in the Tarheel State and a few tourist trains here offer Easter-themed train rides. -

Maryland Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:05 AM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:03 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Indiana Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:01 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 09:58 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Metro-North Unveils Veterans Heritage Locomotive

Feb 28, 26 11:02 PM

The Metro-North Railroad marked Veterans Day 2025 with the unveiling of a striking new heritage locomotive honoring the service and sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Pennsylvania's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:46 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Alabama's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:44 AM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Georgia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:43 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:40 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Mexico Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:37 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:35 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

KC Streetcar Ridership Surges With Opening of Main Street Extension

Feb 27, 26 11:24 AM

Kansas City’s investment in modern urban rail transit is already paying dividends, especially following the opening of the Main Street Extension. -

“Auburn Road Special” Excursions To Aid URHS

Feb 27, 26 09:04 AM

The United Railroad Historical Society of New Jersey (URHS) and the Finger Lakes Railway have jointly announced a special series of rare-mileage passenger excursions scheduled for April 18–19, 2026. -

New Jersey Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:53 AM

New Jersey is home to several museums and a few heritage railroads that vividly illustrate its long history with the iron horse. A few host special events for the Easter holiday. -

Washington Easter Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:49 AM

You can find many heritage railroads in Washington State which illustrates its rich history with the iron horse. A few host Easter-themed events each spring. -

South Dakota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:46 AM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:42 AM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Pennsylvania Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:38 AM

Wine tasting trains are a unique and enchanting way to explore the state’s burgeoning wine scene while enjoying a leisurely ride through picturesque landscapes. -

West Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 27, 26 08:37 AM

West Virginia, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes and rich history, offers visitors a unique way to explore its rolling hills and picturesque vineyards: wine tasting trains. -

Nebraska Lawmakers Advance UP Tax Incentive Bill

Feb 27, 26 08:31 AM

Nebraska lawmakers are advancing new economic development legislation designed in large part to ensure that Union Pacific Railroad maintains its historic corporate headquarters in Omaha. -

UP And NS Ask FRA To Waive Cab-Signals For Big Boy 4014

Feb 26, 26 01:44 PM

Union Pacific’s famed 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” No. 4014 could see new eastern mileage on Norfolk Southern in 2026—but first, the two railroads are asking federal regulators for help bridging a technology gap… -

Cando Rail & Terminals to Acquire Savage Rail

Feb 26, 26 11:29 AM

Cando Rail & Terminals has signed a definitive agreement to acquire Savage Rail, the U.S. rail-services business of Savage Enterprises LLC. -

Dollywood To Convert Steam Locomotives From Coal To Oil

Feb 26, 26 09:20 AM

Dollywood’s most recognizable moving landmark—the Dollywood Express—will soon look and feel a little different. -

Missouri Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:10 AM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:08 AM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Utah Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:04 AM

Utah, a state widely celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty and dramatic landscapes, is also gaining recognition for an unexpected yet delightful experience: wine tasting trains. -

Vermont Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 26, 26 09:02 AM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Amtrak San Joaquins Becomes Gold Runner

Feb 26, 26 08:59 AM

California’s busy state-supported rail link between the Bay Area and the Central Valley entered a new chapter in early November 2025, when the familiar Amtrak San Joaquins name was officially retired. -

Canadian National Marks 30 Years Since Privatization

Feb 25, 26 02:07 PM

Canadian National Railway marked a milestone last fall that helped redefine not only the company, but the modern Canadian freight-rail landscape: 30 years since CN went private. -

Western Rail Coalition: Returning Passenger Trains To Colorado

Feb 25, 26 11:48 AM

Colorado’s passenger-rail conversation is often framed as two separate stories: a Front Range “spine” along I-25, and a harder, longer-term quest to offer real alternatives to the I-70 mountain drive. -

Union Pacific Unveils Full Schedule For Big Boy 4014

Feb 25, 26 09:24 AM

Union Pacific Railroad has released the complete western leg schedule for its groundbreaking 2026 Big Boy No. 4014 Coast-to-Coast Tour. -

Kentucky Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:55 AM

In the realm of unique travel experiences, Kentucky offers an enchanting twist that entices both locals and tourists alike: murder mystery dinner train rides. -

Utah Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:53 AM

This article highlights the murder mystery dinner trains currently avaliable in the state of Utah! -

Rhode Island Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:50 AM

It may the smallest state but Rhode Island is home to a unique and upscale train excursion offering wide aboard their trips, the Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad. -

Oregon Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 25, 26 08:45 AM

For those looking to explore this wine paradise in style and comfort, Oregon's wine tasting trains offer a unique and enjoyable way to experience the region's offerings. -

Amtrak Posts Record Ridership and Revenue in Fiscal Year 2025

Feb 24, 26 11:22 PM

Amtrak, the national passenger rail operator, has announced historic results for Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25), reporting the highest ridership and revenue in its history as demand for train travel across t… -

NC By Train Posts Busiest Month In 35-year History

Feb 24, 26 06:17 PM

North Carolina’s state-supported passenger rail service, marketed under the NC By Train brand, reached a milestone last fall. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision.