Uintah Railway: Map, Roster, Timetables, History

Last revised: September 10, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Among 3-foot, narrow-gauge systems the Uintah Railway was built very late, formed in 1903 by the Barber Asphalt Paving Company - a division of the General Asphalt Company - as a wholly owned subsidiary for the purpose of moving Gilsonite.

The name 'Uintah' was chosen to signify the unique geographical area it would serve - the vibrant, resource-rich region of Uintah Basin in Utah and a part of Colorado.

Gilsonite was a type of asphaltum named after Samuel Henry Gilson who first used the material in 1886 as a varnish and electrical insulation.

The Uintah Railway was built solely to handle this product, opening its initial main line between western Colorado and northeastern Utah in 1904. However, the railroad was also formed as a common-carrier and provided passenger service within this isolated area of the U.S.

The railroad became famous among railfans, and somewhat throughout the industry, for its extremely steep grades and very sharp curves. It operated two of the most unique locomotives ever placed into service, 2-6-6-2T Mallets that spent more than a decade in operation before the railroad closed in 1939.

Photos

One of the Uintah Railway's unique 2-6-6-2T Mallet Moguls, #50, built by Baldwin in 1926. It was one of two the railroad owned.

One of the Uintah Railway's unique 2-6-6-2T Mallet Moguls, #50, built by Baldwin in 1926. It was one of two the railroad owned.History

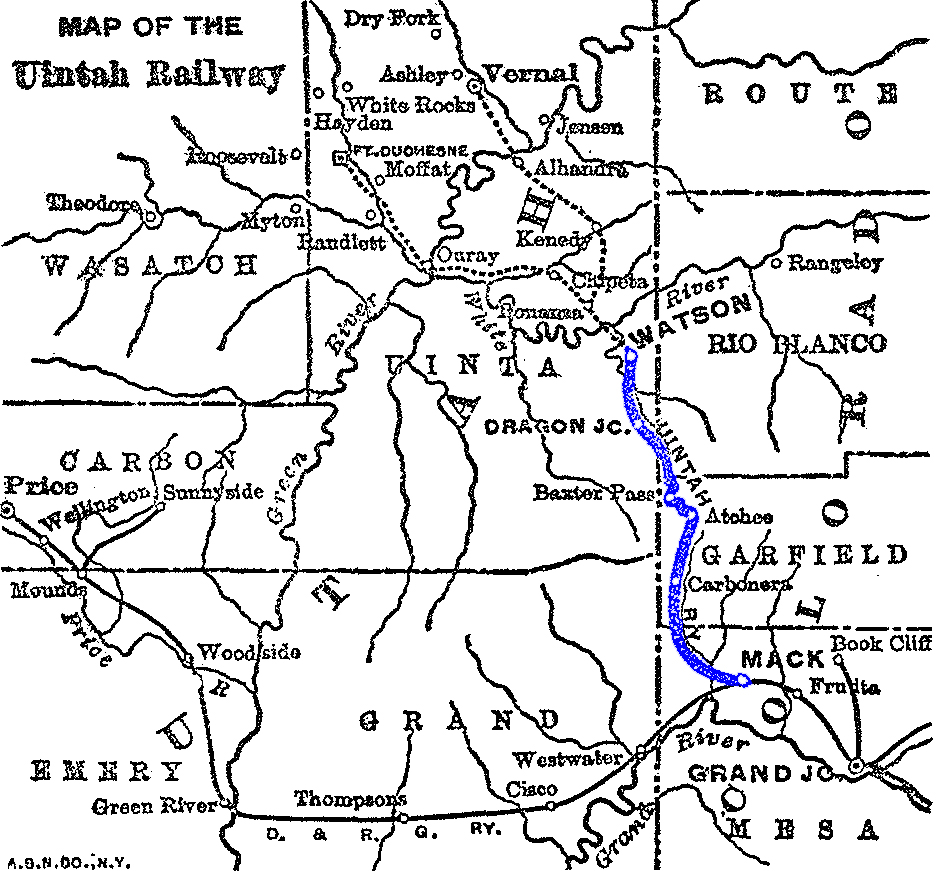

In its decades of operation, the Uintah Railway served multiple towns in both Utah and Colorado. Interestingly, the line originated at the town of Mack, located in Colorado, and spanned the distance to many communities including Watson, Rainbow, Atchee, Dragon, and ended at the town of Watson in Utah.

Other towns indirectly served by the goods and passengers transported along the line included Salt Lake City in Utah and Denver in Colorado.

In the late 19th century Gilsonite, a naturally occurring, solid, black, lightweight mineral pitch that originates from the solidification of petroleum, became popular in everyday products such as paints, varnishes, insulation, flooring, roofing, and other applications.

Today, the commodity is still used in various products including the manufacturing of automotive polish, printer's ink, and even explosive detonators. At the time, the Uintah Basin was the only place in the world where Gilsonite could be mined.

In the early 20th century the area was so rural the only means of economical extraction was via railroad, although building such a transportation artery would require extremely steep grades and sharp curves.

To keep costs down management of the General Asphalt Company decided to build the line to 3-foot, narrow-gauge standards. The Uintah Railway Company's initial route ran 53 miles from a connection with the Rio Grande Western (later Denver & Rio Grande Western) at Mack, Colorado to Dragon, Utah, location of the Dragon Mine.

Building north from the RGW, engineers utilized that railroad's former narrow-gauge road bed (abandoned in 1890 when the railroad was updated to standard gauge) for about 3 miles. It then climbed the West Salt Wash for 28 miles before arriving at Atchee where the route was then forced to negotiate Baxter Pass.

As George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the Uintah Railway actually more closely resembled logging railroads of that era instead of typical narrow-gauge operations.

The grade to the summit of this pass topped out at a grueling 7.5% and featured curves exceeding 60° in some locations.

In fact, the curve at Moro Castle (Milepost 30) was an incredible 75°, easily making it the sharpest found on any common-carrier railroad in the United States. This curve was later amended to 66° but still held the title of most severe.

From Baxter Pass the line descended on 5% grade into McAndrews and then followed Evacuation Creek into Dragon.

The Uintah Railway's traffic was predominantly Gilsonite; it was transported in a somewhat unique fashion by railroad standards, burlap sacks weighing 150-200 pounds each.

Apart from Gilsonite, the railway also transported a range of other freight. This included regular goods such as food, mail, agricultural products, lumber, livestock, and wool which were vital for the towns it served.

Alongside the passenger service, this freight transportation helped bolster local economies and supported the communities along its route.

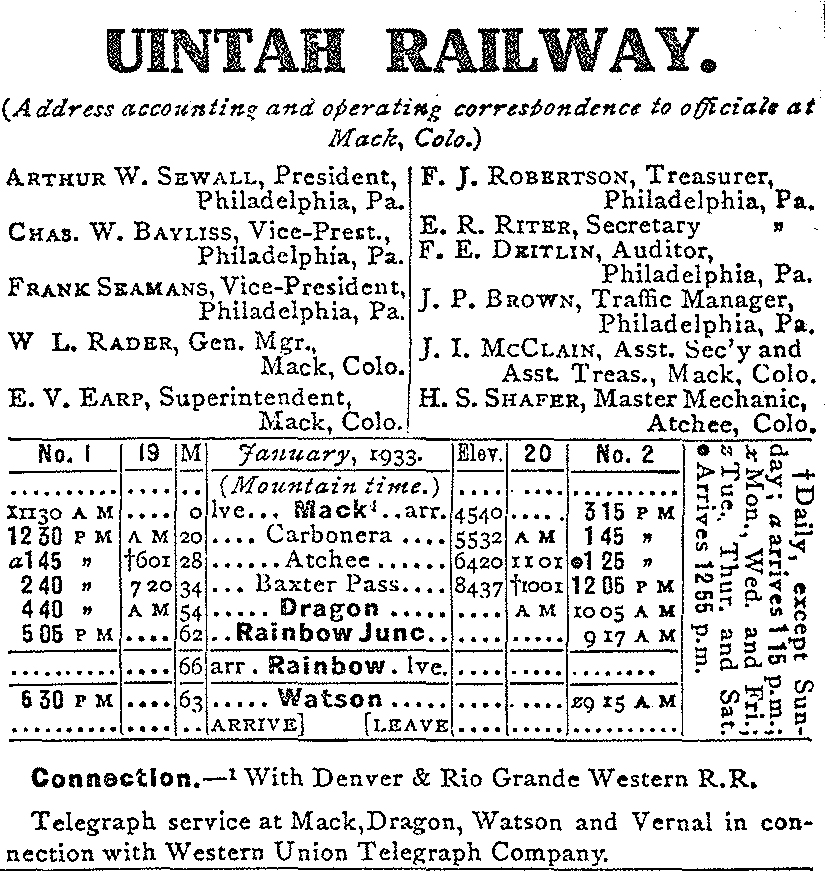

The passenger service on the Uintah Railway exemplified its function as a vital link in the regional transport network. Passenger service started just after the railway's establishment, and continued until 1938. It was much loved by local communities.

After a few years of operation, the railroad began an extension northward beyond Dragon in 1908. Initially, plans were to push rails as far as Vernal (via Bonanza), tunnel Baxter Pass, and update the property to standard gauge.

Ultimately, however, the extension only ran 9.6 miles down Evacuation Creek to Watson and the railroad remained a narrow-gauge operation.

From a location known as Rainbow Junction (about a mile south of Watson) a spur of 4 miles, featuring grades of 5.1%, was extended to Rainbow where the largest deposit of Gilsonite in the region was discovered.

Operations

The railroad's steep grades required the use of geared steam locomotives; in 1910 it acquired five, 2-truck Shays and added a sixth in 1920. All were built by the Lima Locomotive Works. Another, #7, was built by the Atchee Shops in 1933 from the spare parts of #1, #3, and #4 and a new Lima boiler.

2-6-6-2T Mallets

The railroad also operated four standard, 2-8-0 rod engines built by Baldwin, as well as a pair of 0-6-2T tank engines used in passenger assignments, and a pair of standard rod 2-8-2s.

Its most famous engines were a pair of 2-6-6-2T Mallet Moguls acquired from Baldwin in 1926 (#50) and 1928 (#51). This unique, articulated locomotives were capable of operating the entire railroad, including the steep grades and sharp curves of Baxter Pass.

Given the challenging steep terrain along the route, the unique design of the engine allowed it to navigate the mountainous landscape with relative ease. Moreover, their substantial power and size made them a marvel to behold and an integral part of the railway's history.

The 2-6-6-Ts were the only two examples of their type ever built for an American railroad and were widely considered a phenomenal success.

System Map (1933)

Decline

Despite serving a valuable purpose and operating successfully for many years, the Uintah Railway began to decline around the mid-20th century.

This slide was primarily due to the advent of new modes of transportation, most notably the trucking industry, which was on the rise during this period. Additionally, the Great Depression during the 1930s devastated many a railway company, including the Uintah Railway.

The railroad had built a toll road to Dragon, known as the Uintah Toll Road Company, which opened in 1906. It also reached Vernal, Fort Duchesne, and the former Uintah Indian Reservation.

By 1921, the company ended regularly scheduled automobile service between Watson and Vernal and cutback passenger rail service to three-times a week. In 1929 this was reduced to merely a mixed train but ran daily except Sunday.

The General Asphalt Company (which became the Barber Company, Inc. in 1936), despite having still considered extending the railroad to Vernal as late as 1917, had lost interest in the operation by the mid-1930s as an increasing number of roads were built into the area.

The toll road was turned over to the county in 1936 and the railroad applied for abandonment in August, 1938 (by December of that year passenger service was reduced to one mixed train weekly on Tuesdays).

The Interstate Commerce Commission approved the application in April, 1939 and the final train ran on May 16, 1939. By 1940 the entire railroad had been dismantled.

The Uintah Railway's fascinating Mallet Moguls, impressively built track, and other steam engines are still fondly remembered by railroad enthusiasts.

Timetables (1933)

Final Years

The Uintah Railway was an instrumental part of the growth and development of the region it served for more than three decades. Despite the inevitable decline it faced, the railway continues to hold a place of prominence in the history of railroad development in the United States.

It remains a significant symbol of engineering excellence, innovation, and industry. The history and legacy of the Uintah Railway are still preserved through the stories of the people it served, the towns it connected, and the unique natural resource—Gilsonite—it transported.

Sources

- Griffin, James R. Rio Grande Railroad. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2003.

- Hilton, George. American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

Recent Articles

-

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:44 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers.