Virginian Railway's 2-10-10-2 Locomotives

Published: July 28, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The 2-10-10-2 wheel arrangement represents a unique chapter in the evolution of steam engines. Their massive size and power were primarily designed to tackle the challenges of hauling heavy freight over mountainous terrain, where the need for tractive effort was paramount.

The first 2-10-10-2s emerged on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, which ordered a group of ten in 1911. These engines, were not popular on the western road due to their very low speeds and could be used primarily in helper service only. The AT&SF utlimately converted them into 2-10-2s between 1915-1918.

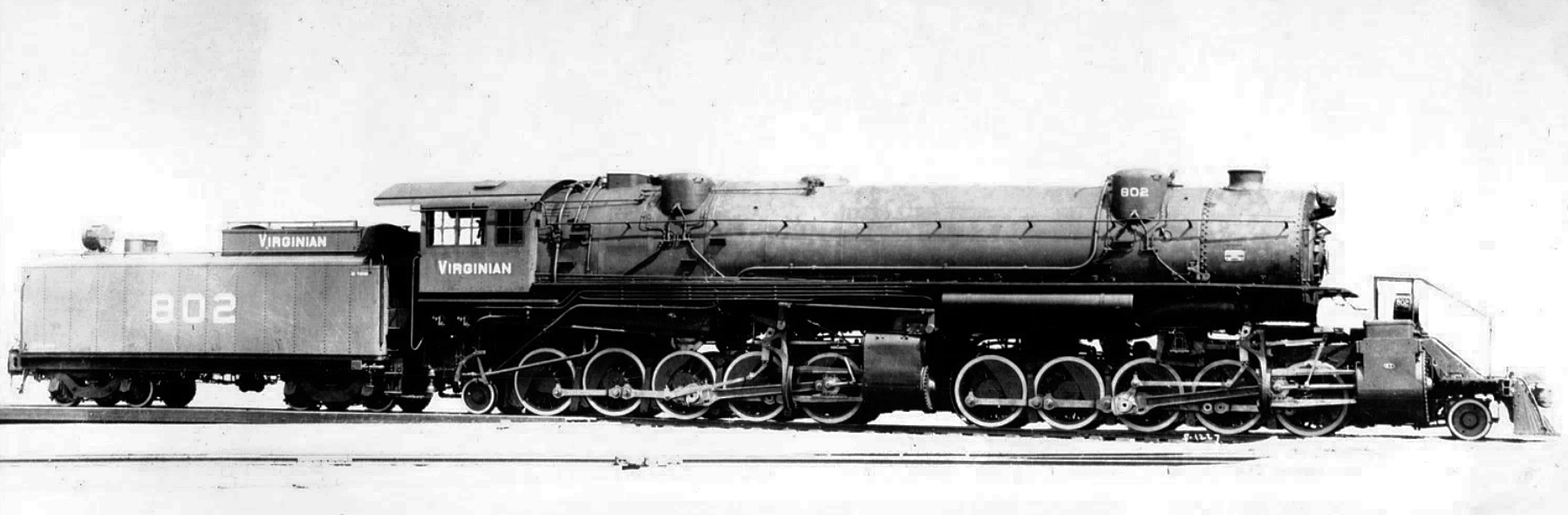

The eastern coal hauler, Virginian Railway, saw much greater success with the design, in part due to their ideal nature in slow drag service. Their ten examples, sporting a relatively short wheel base given their numerous drivers (although at the time were considered massive), arrived in 1918 and remained in regular service until the early 1950s.

The Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway stands as one of the last monumental rail systems in the nation. Forged from the ambitions of oil baron Henry Rogers and the engineering prowess of William Page, its sole mission was to transport coal effectively.

Though its main line stretched under 500 miles, it was a constant thorn in the side of the larger Norfolk & Western due to its stringent construction standards.

Despite its modest size, the Virginian excelled in seamless operations, moving coal from the mines straight to the coast with clockwork precision.

Conceived at the dawn of the 20th century, the railway's inception was swift, propelled by Rogers' substantial financial backing. The 1920s witnessed part of its main line west of Roanoke, Virginia, transitioning to electrification, marking a golden era for the railway.

Initially, boxcabs were used, but they were later supplanted by more robust rectifiers from General Electric.

The constant rivalry drove the N&W to such frustration that they eventually offered top dollar to end the competition, absorbing the Virginian in the late 1950s. Nowadays, much of the Virginian's original main line remains operational, now under the Norfolk Southern banner.

Big Steam

The Virginian is well-known for its use of a large wheel arrangements, including the 2-8-8-2, 2-8-8-0, 2-8-4, 2-6-6-6, and even the gigantic 2-8-8-8-4 "Triplex." As Lloyd Lewis notes in his book, "West Virginia Railroads Volume 4: Virginian Railway," these big engines were acquired for two reasons; handling coal and tackling the 2.07% grades over Clarks Gap Mountain.

These engines were much better proportioned compared to the Erie's Triplexes or the 2-8-8-8-4s previuosly mentioned. Their boiler and grate demand factors were reasonable, allowing the crew to maintain consistent steam, largely thanks to the use of a Duplex or Standard mechanical stoker.

The firebox's heating surface was enhanced by a short combustion chamber. High-pressure cylinders received steam via 16-inch piston valves, while the massive low-pressure cylinders, with a volume of 33.51 cubic feet each, utilized double-ported slide valves. The simple starting tractive effort reached an impressive 176,000 pounds.

They were versatile enough to run in either single or double expansion modes. It's impressive that their giant boilers could maintain steam pressure even at a slow speed of around eight miles an hour.

In December 1921, Alco's Estimating Engineer, James Partington, highlighted the pulling power of these double decapods. One engine hauled a 15,725-ton train from Princeton to Roanoke, burning 26.9 pounds of coal per 1,000 ton-miles. Another 2-10-10-2 handled 110 cars, totaling 17,250 tons, over a tough grade of 0.2%.

Shipment Issues

The 2-10-10-2s may not have matched later articulated models in size, but with an almost 100-foot-long wheelbase, they were undeniably giants of their time.

However, many foreign railroads faced challenges handling these behemoths as the engines made their way to the Virginian due to more restrictive clearances—notably less generous than those of the Virginian, which was renowned for its accommodating space.

The low-pressure cylinders, measuring a massive 48 inches, were record-setting in size for any locomotive in the U.S. They were so large that they had to be installed at a slight upward angle for proper clearance. Interestingly, due to the constraints of the Virginian turntables, these locomotives had unusually small tenders.

Before these engines set off from American Locomotive's Schenectady Works, a few adjustments were necessary: the steam and sand domes, the spacious cab, and the massive front-end high-pressure steam cylinders were all removed, photographed, and packed onto a preceding gondola, ensuring a slow but steady journey southward.

Data Sheet

| Road Numbers | 800–809 |

| Number Built | 10 |

| Builder | Alco |

| Year | 1918 |

| Valve Gear | Walschaert |

| Driver Wheelbase | 39' 8" |

| Engine Wheelbase | 64' 3" |

| Overall Wheelbase | 97' 0" |

| Axle Loading | 61,712 Lbs |

| Weight on Drivers | 617,000 Lbs |

| Engine Weight | 684,000 Lbs |

| Tender Loaded Weight | 214,300 Lbs |

| Total Engine and Tender Weight | 898,300 Lbs |

| Tender Water Capacity | 13,000 Gallons |

| Tender Fuel Capacity (coal/tons) | 12 |

| Minimum Rail Weight | 103 Lbs |

| Driver Diameter | 56" |

| Boiler Pressure (psi) | 215 |

| High Pressure Cylinders | 30" x 32" |

| Low Pressure Cylinders | 48" x 32" |

| Tractive Effort | 135,170 Lbs |

| Factor of Adhesion | 4.56 |

The AEs operated effectively for 30 years, initially as pushers until replaced by electric engines, and later as helpers on other grades. The engines remained largely unaltered, except for the addition of Worthington BL feedwater heaters. These workhorses served reliably for 34 years until their retirement in 1952, by which diesels and electrics had largely replaced Virginian's steam fleet.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.