Railroads In The 19th Century (USA)

Last revised: February 27, 2025

By: Adam Burns

As T.J. Stiles points out in his authoritative title, "The First Tycoon: The Epic Life Of Cornelius Vanderbilt," the railroad fundamentally changed the United States in far more ways than simply improved transportation.

It ushered in the modern, corporate America we know today where huge conglomerates preside over nearly every facet of our lives. The railroad was the first business of its kind to employ thousands, serve millions, and capitalized in the hundreds of millions.

They directly impacted numerous, intercity municipalities although, ironically, were privately owned ventures.

As the 19th century dawned no one could have imagined such incredible machines would soon exist to whisk freight and passengers at previously unheard-of speeds. But as with all technologies the railroad was slow to develop.

Timeline

After the steam-powered Stockton & Darlington Railway debuted in England during 1825 the first rudimentary, non-steam powered systems appeared in the United States the following year.

However, more than a decade would pass before railroading truly took hold in America. By 1840 railroads were here to stay although many technological developments remained before efficient, safe operations became commonplace.

Photos

One of the first steam locomotives manufactured in the United States was the Baltimore & Ohio's 0-4-0 #2, the "Atlantic," completed in 1832 by Phineas Davis and Israel Gartner of York, Pennsylvania. The original "Atlantic" was scrapped in 1835 but its sister, the "Andrew Jackson" (#7), built by Davis and Gartner in February, 1836, still survives today at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum where it masquerades as the "Atlantic." Author's collection.

One of the first steam locomotives manufactured in the United States was the Baltimore & Ohio's 0-4-0 #2, the "Atlantic," completed in 1832 by Phineas Davis and Israel Gartner of York, Pennsylvania. The original "Atlantic" was scrapped in 1835 but its sister, the "Andrew Jackson" (#7), built by Davis and Gartner in February, 1836, still survives today at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum where it masquerades as the "Atlantic." Author's collection.1820s

As Mr. Stiles' book notes, early U.S. railroads were not conceived to provide interstate, or even intrastate, travel. Instead, they were constructed entirely for specific needs. Take, for instance, America's first, the Granite Railway of Massachusetts.

It opened on October 7, 1826 carrying a wide gauge of 5 feet. The line was only 3 miles in length and entirely horse or mule-powered. Its entire purpose was to transport granite slabs between Quincy and the Neponset River (Milton) for construction of the Bunker Hill Monument project.

In an era long predating the modern, all-steel "T" rail, the Granite Railway utilized massive stone rails. This was unique and rare even for that time period when many engineers were employing the cheaper, and lighter, strap-iron technique. During the late 1820's several projects were underway up and down the eastern seaboard.

One of the first was the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad, incorporated on April 17, 1826 to connect the Hudson River at Albany with the Mohawk River at Schenectady. It was designed as a shortcut to compete against the heralded Erie Canal for transporting people and goods between Schenectady and Albany (state capital).

1830s

Due to funding issues it took more than four years until construction began and was not completed until August 9, 1831.

On that day a little 0-4-0, named DeWitt Clinton, pulled the first load of paying customers, earning it recognition as the first steam locomotive to operate in New York.

The long delay in M&H's completion meant other operations were credited with various "firsts." Most notable was the Baltimore & Ohio.

The B&O was created largely out of a great need by the city of Baltimore to compete with the Erie Canal, which connected New York City with the Port of Albany at Buffalo. In addition, Philadelphia was organizing a plan to build a similar transportation system across the state linking Pittsburgh.

Fearing its city would be left at an economic disadvantage Baltimore leaders formed the B&O, originally chartered on February 28, 1827. In January, 1830 the B&O launched service over its first 1.5 miles from a small station in Baltimore at Pratt Street. That same summer (August 28th) the railroad successfully tested Peter Cooper's 2-2-0 "Tom Thumb."

It lost its famous race with a horse that day but nevertheless proved the steam locomotive's viability. Cooper's contraption is also credited as the first American-built design ever placed into use although, as a test-bed unit, was never actually operated in regular service.

Overview (1820s/1830s)

1,000 (1835) 2,808 (1840) |

|

* Fewer than 100 early stagecoach cars were manufactured in the United States according to John White, Jr.'s book "The American Railroad Passenger Car: Part 1."

Sources (For Above Table):

- White Jr., John H. American Railroad Passenger Car, The: Part 1. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1985 edition.

- White Jr., John H. American Railroad Freight Car, The: From The Wood-Car Era To The Coming Of Steel. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

Another important railroading pioneer was the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company. According to Jim Shaughnessy's book, "Delaware & Hudson: Bridge Line To New England And Canada," it was conceived by brothers Maurice and William Wurts to transport clean-burning anthracite coal from mines near Carbondale, Pennsylvania to New York City for home and commercial heating purposes.

Their original plans called for a duel, canal/gravity railroad. The latter was designed by John B. Jervis and the company ordered four steam locomotives from England to handle the necessary tonnage. Only one would ever be used, the Stourbridge Lion, manufactured by Foster, Rastrick & Company of Stourbridge, England.

Jervis tested the little 0-4-0 on August 8, 1829 but sadly it proved too heavy for the track. Despite this setback the little locomotive earned distinction as the first standard design ever operated in the United States.

The next significant development occurred on the South Carolina Canal & Rail Road Company, a system based in Charleston, South Carolina.

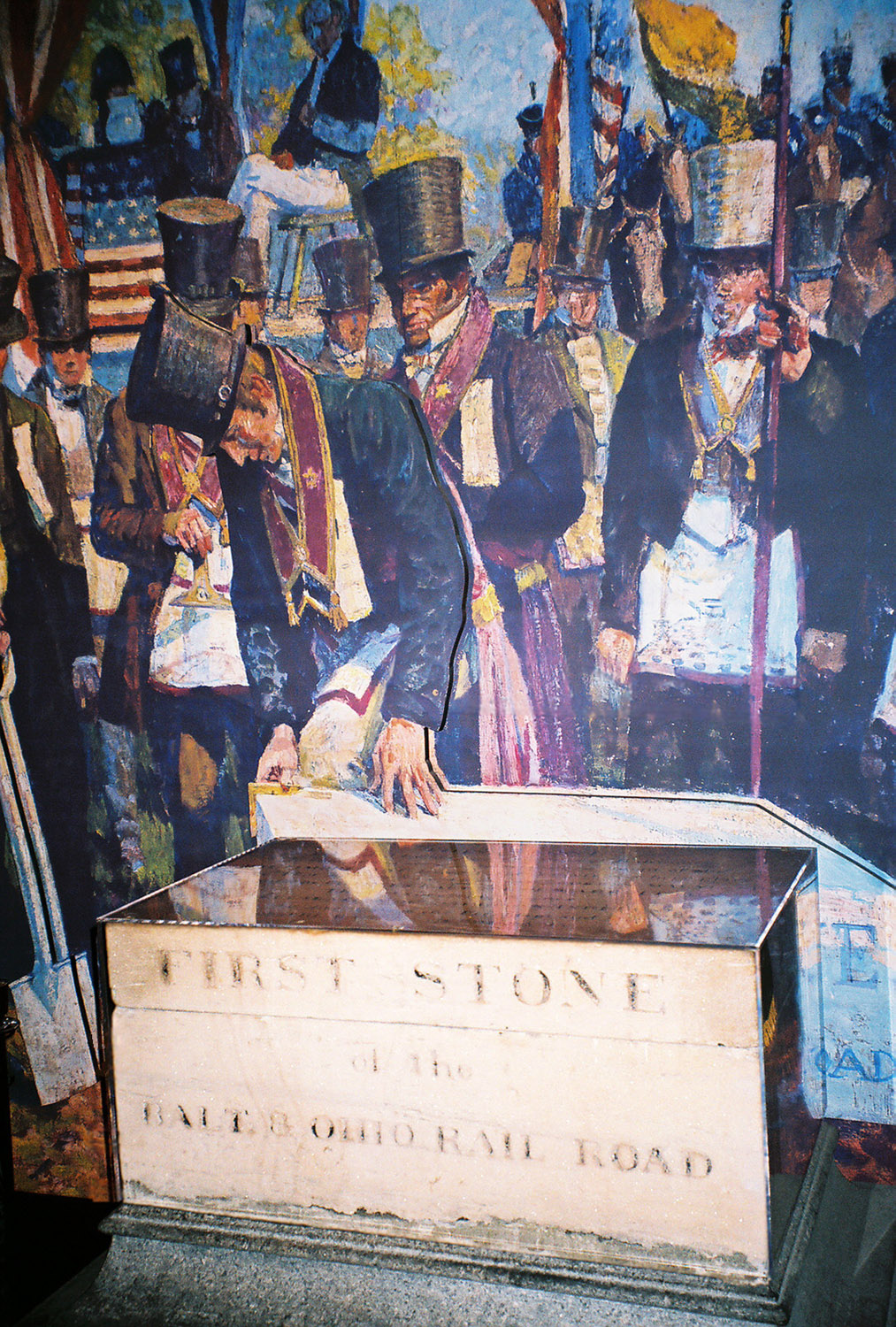

Birth of an industry, the laying of the first stone by Charles Carroll on the Baltimore & Oho Railroad, our country's first common carrier, which took place on July 4, 1828. It is now displayed at the B&O Railroad Museum. Author's collection.

Birth of an industry, the laying of the first stone by Charles Carroll on the Baltimore & Oho Railroad, our country's first common carrier, which took place on July 4, 1828. It is now displayed at the B&O Railroad Museum. Author's collection.The SCC&RR was the longest railroad of its day when it opened 136 miles between Charleston and Hamburg (near Augusta, Georgia) during October, 1833. The project's purpose was, once again, to serve a specific need.

In this case, the port of Charleston wanted to haul agricultural products from inland farms, notably cotton, to the city for shipment. It was formed on December 19, 1827 and began construction thereafter.

Aside from its length and importance the SCC&RR also carries the honor as the first to operate an American-built steam locomotive in revenue service when the Best Friend Of Charleston (built by the West Point Foundry of Cold Spring, New York) carried a trainload of paying customers on December 25, 1830.

Another noteworthy railroad was New Jersey's Camden & Amboy, formed on February 4, 1830 as the Camden & Amboy Rail Road Transportation Company.

A project of Robert Stevens it was envisioned to link the Delaware River at Philadelphia with the Raritan River, which ran into New York City. Many railroads of this era were built specifically to complement either preexisting canals or highly trafficked waterways.

This was the case for the C&A which began construction in December, 1830 at Bordentown, New Jersey. The first 13 miles to Hightstown opened to the public on October 1, 1832. Its first steam locomotive, the 0-4-0 John Bull (built by the Robert Stephenson & Company of England) entered service in 1833.

The locomotive is significant due not only to its early design but also modifications which later became standard on future models; C&A personnel added a lead bogie (truck) to decrease derailments (giving it a 2-4-0 wheel arrangement), a pilot (cow-catcher) to move animals off the right-of-way, a covered cab for the crew's protection against the weather, headlight, bell, and even a covered tender.

By then it had become part of the much larger United Canal & Railroad Companies. (The C&A would later join the growing Pennsylvania Railroad [PRR[ in 1871.) Also of note was Philadelphia's Main Line, a combination canal and rail artery built during the 1830s to connect western Pennsylvania with the Ohio River.

Unfortunately it was much too cumbersome; the canal operation was eventually scrapped and the rail corridor turned over to the PRR. The early railroads dealt with much more than just engineering and logistical issues.

Not everyone was sold on the newfangled technology and canal owners lobbied heavily to suppress or outright deny their construction.

The public had justifiable safety concerns although in some cases the dangers were completely exaggerated. As John Stover points out in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," some of the more ridiculous assertions claimed they were a "device of the devil" and could cause a "concussion of the brain."

Development

While England could proclaim itself as railroading's birthplace, by 1840 its total mileage (1,500) had been far surpassed by the United States. Interestingly, the financial Panic of 1837 did not seriously inhibit railroad construction, unlike later on when these economic recessions seriously stunted additional mileage.

As previously discussed, the B&O was a pioneer in nearly every facet. Its value in advancing new techniques, which later became standard practice, can also not be understated.

As by Kirk Reynolds and David Oroszi note in their book, "Baltimore & Ohio Railroad," nearly everything decision it made was an educated guess based on what little was known about railroads and engineering practices at the time.

Perhaps most challenging was constructing a proper right-of-way and figuring out the curvature limits and gradient a typical train could handle.

To aid in this endeavor its engineers sailed to England for ideas concerning these topics. Among their most notable takeaways was track gauge; English lines were utilizing a width of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches which was ultimately adopted by the B&O.

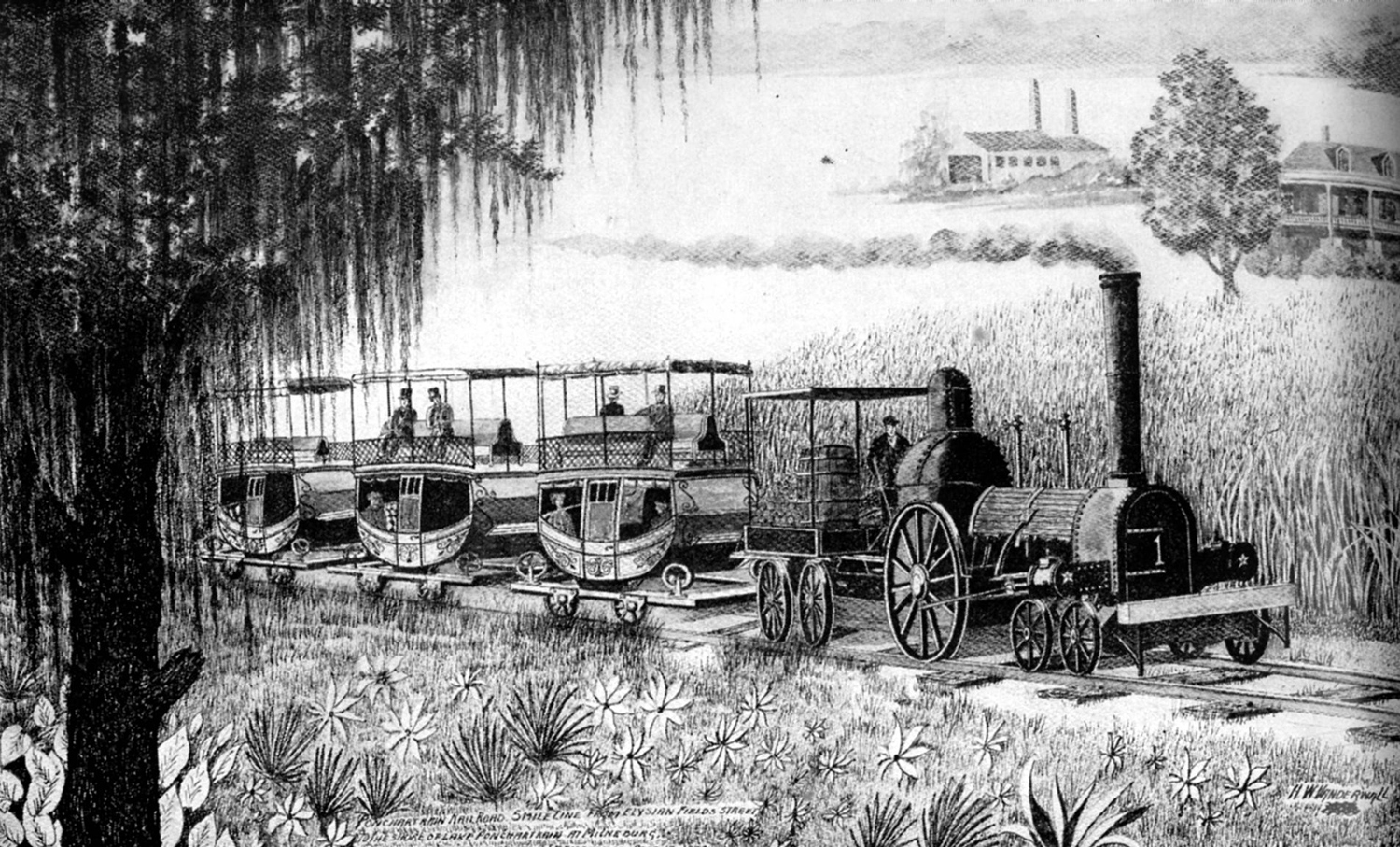

An engraving by H.W. Wanderwall depicting the early Pontchartrain Rail-Road (chartered 1830 and commenced service in 1831) which connected Elysian Fields Street in New Orleans to the shores of Lake Ponchartrain at Milneburg, a distance of 5 miles.

An engraving by H.W. Wanderwall depicting the early Pontchartrain Rail-Road (chartered 1830 and commenced service in 1831) which connected Elysian Fields Street in New Orleans to the shores of Lake Ponchartrain at Milneburg, a distance of 5 miles.Its next task was in designing a track guideway for the trains' wheels to follow. Once again, engineers found themselves in unknown territory as they experimented with various techniques from stone guideways with wooden beams to iron straps using the same principle.

They eventually learned the best, most economical design was a wooden beam reinforced with a iron strap supported by wooden crossties.

Iron strap rails did work although proved incredibly dangerous as worn straps could let go causing the deadly phenomenon of "snake heads," which easily ripped through the floors of early wooden cars and maimed or killed passengers.

Finally, engineers had to conceive a right-of-way capable of handling this new form of technology. Once more, with no books or prior research to guide them, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen H. Long of the U.S. Army who was overseeing survey work, and Johnathan Knight, a civil engineer simply made educated guesses.

The B&O would initially use horses to power their trains with the intentions of one day switching to steam propulsion. As a result, Knight and Long used very conservative figures, limiting the ruling grade to a very respectable 0.6% (or a mere 6 inches of elevation for every 100 feet traveled).

Interestingly, they allowed curves to be relatively sharp at 14-18 degrees, unaware the length trains would one day reach. Future practice would allow for stiffer grades with less severe curves.

Early Freight And Passenger Cars

Gaining a true understanding of early railroad car development can be difficult due to anecdotal stories or just outright misinformation. It is further complicated by the lack of historical documents available.

If you are interested in this subject three books on the topic are a must, all written by John H. White, Jr.: "The American Railroad Passenger Car" (Parts I and II) and "The American Railroad Freight Car." As he notes, the story of America's first passenger cars built from stagecoaches remains widely told to this day.

In reality, while these were influenced from stagecoaches and manufactured by stagecoach builders, they were actually designed from the chassis up.

The first known passenger car contract was awarded to Richard Imlay of Baltimore in 1828 when the Baltimore & Ohio approached him about supplying the company with equipment.

The first, based from the standard mail coach of the day, was named the Pioneer and placed into service during May, 1830. It was followed by five more nearly identical designs that same August.

Information on freight cars from this period is even more scarce since the public paid little attention to such things and there were no agencies in place to monitor railroads.

In this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo, probably from the 1960's, the replica 4-2-0 "Lafayette" is featured. The locomotive was originally built by William Norris of Philadelphia in 1837. The original was scrapped in 1863 but a replica was completed in 1893. This particular locomotive was the B&O's first to feature a horizontal boiler supported by three axles. It was also the B&O's first to boast horizontal cylinders and connecting rods between the pistons and drivers. Author's collection.

In this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo, probably from the 1960's, the replica 4-2-0 "Lafayette" is featured. The locomotive was originally built by William Norris of Philadelphia in 1837. The original was scrapped in 1863 but a replica was completed in 1893. This particular locomotive was the B&O's first to feature a horizontal boiler supported by three axles. It was also the B&O's first to boast horizontal cylinders and connecting rods between the pistons and drivers. Author's collection.Impact

The previously mentioned Granite Railway employed a basic, reinforced wooden flatcar designed by Gridley Bryant which utilized horse power to transport the marble over huge stone rails. Again, during an era without reliable references ideas and concepts were abundant.

According to Mr. White's book:

"The first series of cars were carried by four wagon wheels. The stones were carried below the axles on a platform raised or lowered by a hand-powered winch fastened to a wooden truss frame that stood above the wheels." For such an early period these cars were well crafted, finely built contraptions.

Bryant's concept proved so successful that it remained unchanged until the original Granite Railway system was abandoned in 1866.

In 1830, and throughout that decade, most freight was transported in either a flatcar, a simple gondola (A simple flatcar with short sides to hold ladding [freight], it is more commonly known as the gondola.

The first is credited to the Baltimore & Ohio of 1832 which referred to it as a "flour car" since it handled barrels of flour.), or an early type of hopper known as a "jimmie." The latter predominantly handled anthracite coal, such as the small, 1,600-pound cars found on the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company at Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania.

These small cars could handle about 3,000 pounds each and transported anthracite coal from open-pit mines near Mauch Chunk over a 9-mile, 42-inch gauge railroad to the Lehigh River where the product was carried on to eastern points such as Philadelphia.

As the 1840's dawned, railroads were becoming a unified network but much work remained at established a system capable of efficient, interstate service.

Recent Articles

-

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail.