Union Pacific "Big Boy" Locomotives: Specs, Preserved, Photos

Last revised: February 25, 2025

By: Adam Burns

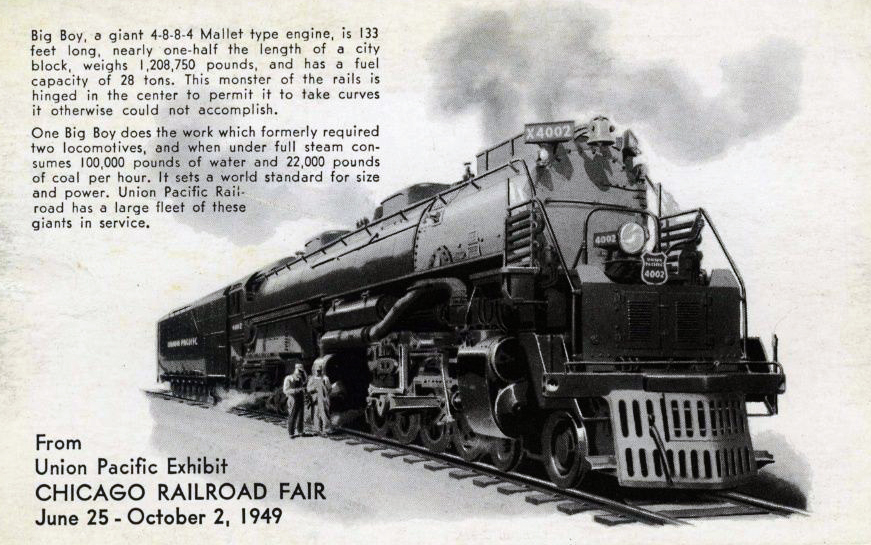

Few steam locomotives compare to Union Pacific's (UP) colossus 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy." It was designed during the zenith of seam technology and earned celebrity status as soon as the first debuted in 1941.

According to David P. Morgan's article, "Big Boy" from the November, 1958 issue of Trains Magazine, the locomotive was mentioned 521 times in newspapers within 45 different states!

It was also highlighted in magazines and on television. The 4-8-8-4 wasn't an experiment; it was designed specifically to handle heavy freight trains, daily, through the Wasatch Mountains.

It did so admirably for nearly two decades. This period also began UP's high horsepower era (which continued through the diesel age); an attempt to lower operating costs via massive, single unit locomotives.

History

The Big Boy's arrived in two batches from American Locomotive, the first 20 were delivered in 1941 and the final 5 three years later. The 4000's were retired in 1959 but a few remained stored into the early 1960's.

Thankfully, eight of these magnificent beasts survive today. On May 2, 2019, after a three year restoration, Union Pacific brought #4014 back to life where she operates as part of the company's official heritage fleet.

Photos

Union Pacific "Big Boys" #4013 and #4003 layover near the shops at Cheyenne, Wyoming, circa 1957. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific "Big Boys" #4013 and #4003 layover near the shops at Cheyenne, Wyoming, circa 1957. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.Background

By the time the first Big Boy, #4000, rolled out of American Locomotive's plant in Schenectady, New York during September, 1941 diesels were already the future in freight transportation.

Electro-Motive had introduced its new FT demonstrator set in May, 1939 and sales immediately took off. However, Union Pacific, and a handful of others (Norfolk & Western and Chesapeake & Ohio, in particular) elected to stick with steam's proven capabilities.

Laying just a stone's throw from Ogden are Utah's Wasatch Mountains, a beautiful but rugged range that plagued UP since it first reached this location during the 1860's. Its busy Overland Route main line boasted a ruling grade of 1.14%.

In 1936 UP introduced its latest locomotive to tackle these steep grades, the 4-6-6-4 designed by A.H. Fetters. Nicknamed "Challengers" they could produce a tractive effort of 97,350 pounds.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4022 heads west at Speer, Wyoming on August 31, 1958. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4022 heads west at Speer, Wyoming on August 31, 1958. American-Rails.com collection.However, even these powerful steamers still required helpers or double-heading to move a 3,600-ton train over the mountain.

Looking for a single unit to do the job, UP's Department of Research & Mechanical Standards (DoRMS), led by Vice President Otto Jabelmann, came up with a new design that was not only powerful but also faster.

Top Speed

In collaboration with the American Locomotive Company (Alco), Jabelmann and Fetters discovered that beefing up the current 4-6-6-4 design would achieve the desired results by increasing the firebox's size, lengthening the boiler, adding two additional sets of drivers, and shortening the driving wheels from 69 to 68 inches.

Through these changes the new 4-8-8-4 offered tractive efforts exceeding 135,000 pounds and could operate at speeds up to 80 mph (although no Big Boys ever actually reached such in service).

The locomotive needed to be powerful for good reason. While the Wasatch Range was not nearly as challenging as other mountainous territory it was Union Pacific's primary east-west corridor with trains (both freight and passenger) typically traveling at speeds above 50 mph.

To sustain such transit times a locomotive like the Big Boy was needed to move expedited fruit blocks and time freights quickly.

The most challenging aspect of this territory was Wyoming's Sherman Hill which sat at 8,013 feet above sea level. In their book, "Union Pacific Railroad," authors Joe Welsh and Kevin Holland note this location was also the highest point on the system where westbound trains had to contend with grades of 1.55%.

This difficult stretch was later improved when the railroad carried out a major line upgrade that reduced the westbound track's maximum gradient to 0.82%.

Work on the project began in July, 1952 and was completed on February 16, 1953. At a cost of $16 million it was 9.5 miles longer (42 miles) than the original corridor. Nevertheless it was able to cut transit times by 15 minutes.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4013 and F7B #1478-C (and likely at least one more F unit out of picture) lead a westbound freight over Sherman Hill at Granite, Wyoming, circa 1957. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4013 and F7B #1478-C (and likely at least one more F unit out of picture) lead a westbound freight over Sherman Hill at Granite, Wyoming, circa 1957. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.Specifications

1,189,500 Lbs (Class 1) 1,208,750 Lbs (Class 2) | |

#4000-4019: $250,000/each #4020-#2024: $319,600/each | |

Sources

Solomon, Brian. Alco Locomotives. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2009.

"Big Look At Big Boy." Trains Magazine. May, 1956: 31-39. Print.

"Union Pacific 4000 Series." Trains Magazine. July, 1943: 24-27. Print.

"Famous Steam Locomotives 6: Union Pacific's Big Boy." Trains Magazine. August, 1952: 58-59. Print.

Morgan, David P. "Big Boy...That's What An Alco Workman Chalked On The Smokebox Of The World's Heaviest Locomotive Back In 1941, And No One Has Ever Seen Fit To Dispute The Name." Trains Magazine. November, 1958: 40-51. Print.

"Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" Locomotives in the USA." SteamLocomotive.com.

* Brian Solomon's notes in his book, "Alco Locomotives," that Alfred Bruce noted the Big Boy at 7,500 horsepower while the Trains Magazine article, "Union Pacific 4000 Series." mentioned it could produce 7,000 horsepower with a maximum speed of 80 mph.

** This was measured on April 3, 1943 when Union Pacific utilized Santa Fe dynamometer car #29 to test #4016's performance.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4004 stops for a drink at the water tank in Red Buttes, Wyoming at the base of Sherman Hill on August 30, 1958. James Ehernberger photo. Author's collection.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4004 stops for a drink at the water tank in Red Buttes, Wyoming at the base of Sherman Hill on August 30, 1958. James Ehernberger photo. Author's collection.Suppliers

Railway Age Editor-In-Chief William C. Vantuono notes in his article, "Requiem For a Heavyweight" published on May 9, 2019 the following suppliers aided in the Big Boy's construction:

- Adirondack Foundries & Steel

- American Arch

- American Brake Shoe & Foundry

- American Throttle

- Barco Manufacturing

- Bethlehem Steel

- Buckeye Steel Castings

- Carnegie-Illinois Steel

- Champion Rivet

- Chase Brass & Copper

- Elastic Stop Nut

- Electro Chemical Engineering

- Flannery Bolt Company

- Franklin Railway Supply

- Garlock Packing

- Gatke Corporation

- General Steel Castings

- Gustin-Bacon Manufacturing

- Hewitt Rubber

- Homer D. Bronson Company

- Johns-Manville Corporation

- Jos.eph T. Ryerson & Son

- Lunkenheimer Company

- Masonite

- Nathan Manufacturing

- National Lock Washer

- National Tube

- New York Air Brake

- Phelps Dodge Copper Products

- Pittsburgh Plate Glass

- Prime Manufacturing

- SKF Industries

- Standard Stoker

- Superheater Company

- Symington-Gould

- Timken Roller Bearing

- Tube-Turns Inc.

- T-Z Railway Equipment

- Ulster Iron Works

- Union Asbestos & Rubber

- U.S. Rubber

- Waugh Equipment

- Westinghouse Air Brake

- W.M. Sellers & Company

- Wilson Engineering

According to Brian Solomon's book, "Alco Locomotives," the first Big Boy (#4000) was delivered to Union Pacific at Omaha, Nebraska on September 4, 1941.

As the story goes the locomotive's name came from an unidentified Alco employ who scrawled "Big Boy" on the smokebox door with a "V" for victory in World War II. It entered service shortly thereafter lugging a train of more than 100 cars.

Union Pacific would go on to roster two distinct classes of 4-8-8-4's listed simply as Class 1 (#4000-4019) and Class 2 (#4020-4024) with Alco delivering the final locomotive in 1944.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4009 steams out of Laramie, Wyoming on September 7, 1956. J.E. Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4009 steams out of Laramie, Wyoming on September 7, 1956. J.E. Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.Although oil was a commonly used fuel by the 1940's, UP elected to power its Big Boys with coal since the railroad owned several mines in Wyoming; interestingly, #4005 was tested briefly as an oil burner but the railroad was not satisfied with the results (with improvements in technology, #4014 has been converted to an oil burner).

The Big Boys went on to tackle not only the grades east of Ogden but also worked the Wyoming Division over Sherman Hill east of Lamarie.

Because the diesel was already proving itself during the Big Boy's development, the 4-8-8-4's enjoyed only a short service life. In spite of this they performed faithfully and flawlessly for nearly two decades.

The famous Union Pacific publicity photo featuring 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4019 with westbound reefers near Echo, Utah (east of Ogden) in 1942.

The famous Union Pacific publicity photo featuring 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4019 with westbound reefers near Echo, Utah (east of Ogden) in 1942.Negotiating Curves

With a length of more than 132 feet (Which prevented operation across much of the system due to lack of adequate turntables. Only 135-footers were in service at Cheyenne, Laramie, Green River, and Ogden.) many wonder how a locomotive as large as the Big Boy could ever negotiate curves without derailing.

The answer can partially be found in its articulation while American Locomotive explained the design challenges of the 4-8-8-4 due to its immense weight. The solution was what the builder described as "lever control." This engineering feat is mentioned in greater detail here.

Essentially, it enabled Alco and UP to manufacture a large and powerful wheel arrangement by designing a three-point suspension that prevented the Big Boy's massive wheel base from binding in curves or lifting off the rails.

It also tackled the issue of counterbalancing, always a tricky proposition, particularly as length and weight increases.

Pulled from retirement to handle a surge in freight business, Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4007 steams westbound as it climbs Sherman Hill on the new single-track, low-grade line west of Cheyenne, Wyoming on a late summer's afternoon in 1958. James Ehernberger photo. Author's collection.

Pulled from retirement to handle a surge in freight business, Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4007 steams westbound as it climbs Sherman Hill on the new single-track, low-grade line west of Cheyenne, Wyoming on a late summer's afternoon in 1958. James Ehernberger photo. Author's collection.The last revenue run of a 4-8-8-4 occurred on July 21, 1959. Afterwards, the railroad stored four, serviceable at Green River, Wyoming until September, 1962. The Big Boy is often mentioned as the largest steamer ever built; sometimes even the most powerful.

In some respects this is true but not others. For example, the Norfolk & Western's 2-8-8-2 Y6 Class and Chesapeake & Ohio's 2-6-6-6 Alleghenies (Class H-8) were themselves monsters, more powerful and larger than the Big Boy in the areas of tractive effort, weight, length and horsepower.

While the argument among historians and enthusiasts of the "largest" and "most powerful" will likely for forever be debated what cannot is the locomotive's preservation; no fewer than eight Big Boys have been saved, currently scattered around the country on display.

They include numbers; 4004-4006, 4012, 4014, 4017, 4018, and 4023. The #4014 has earned global attention since Union Pacific announced its restoration in 2012.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4020 leads an expedited freight of reefers westbound over Wyoming's Sherman Hill on October 4, 1957. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4020 leads an expedited freight of reefers westbound over Wyoming's Sherman Hill on October 4, 1957. American-Rails.com collection.4014

This tantalizing news leaked on December 7th as the railroad contemplated restoring one to operational condition for the railroad's 150th celebration in 2019.

After a few months of further discussions with the Southern California chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society of Pomona, California, which owned #4014, the locomotive was acquired in July, 2013.

During early 2014 the massive 4-8-8-4 was moved from its long-time resting place at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds, a spectacle widely documented by numerous media outlets.

Finally, a major event occurred on the night of May 1, 2019 when #4014 moved out of the Cheyenne Roundhouse under its own power for the first time since making its final run on July 21, 1959. The following day she stretched her legs by making a test run to Greeley, Colorado.

On May 9th she, along with 4-8-4 #844, participated in the Transcontinental Railroad's sesquicentennial. Today, she operates as part of UP's heritage fleet pool which includes 4-8-4 #844, DDA40X "Centennial" #6936, and a handful of "E" units to pull special excursions around the system.

Preserved Examples

| Engine Number | Wheel Arrangement | Track Gauge | Original Owner | Current Location | Current Status | Builder Information | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4014 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Cheyenne, Wyoming Roundhouse | Operational | Alco-Schenectady #69585 (11/1941) | Acquired from RailGiants Train Museum (Pomona, California in July, 2013). Restored to operation on May 1, 2019. |

| 4004 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Holliday Park (Cheyenne, Wyoming) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #69575 (9/1941) | - |

| 4005 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Forney Transportation Museum (Denver) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #69576 (10/1941) | - |

| 4018 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Museum of the American Railroad (Frisco, Texas) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #69589 (1/1942) | - |

| 4017 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | National Railroad Museum (Green Bay) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #69588 (1/1942) | - |

| 4023 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Lauritzen Gardens (Omaha) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #72780 (11/1944) | - |

| 4012 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Steamtown National Historic Site (Scranton, Pennsylvania) | Display | Alco (Schenectady) #69583, 11/1941 | - |

| 4006 | 4-8-8-4 | 4' 8 ½" | Union Pacific | Museum of Transportation (St. Louis) | Display | Alco-Schenectady #69577 (10/1941) | - |

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.