Railroad Car Ferries: History, Purpose, Photos

Published: January 31, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Car ferries occupy an intriguing niche within the wider landscape of transportation and industrial history. These vessels, designed to carry railroad cars across bodies of water, represent a vital solution to connecting disparate rail networks.

During the very early years of railroading - predominantely during the mid-19th century - ferries could be found in service across many rivers of notable size as bridges had yet to be constructed.

By the 20th century the service had transitioned into much more organized and isolated operations due to their expense and dwindling need.

Notable operations through the mid-20th century include locations such as the New York Harbor, San Francisco Bay, the Great Lakes, and Puget Sound.

This article explores the history, technology, and legacy of car ferries, providing a comprehensive understanding of their impact on trade and infrastructure.

Soo Line GP30 #708 loads the "S.S. Chief Wawatam" at the St. Ignace, Michigan docks during June of 1979. This service was provided in conjunction with the Detroit & Mackinac via Mackinaw City. Rob Kitchen photo.

Soo Line GP30 #708 loads the "S.S. Chief Wawatam" at the St. Ignace, Michigan docks during June of 1979. This service was provided in conjunction with the Detroit & Mackinac via Mackinaw City. Rob Kitchen photo.Historical Context and Development

The concept of ferrying railroad cars across water is rooted in the larger narrative of industrial expansion during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

As railroads began to crisscross continents, geographical barriers such as lakes, rivers, and straits presented significant logistical challenges. The burgeoning demand for the efficient movement of freight and passengers necessitated innovative approaches to bridge these divides.

The earliest recorded ferry was the Leviathan, which began service in 1836, on the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. Although manually powered, it set a precedent for the potential of such service.

The practice became more widespread with the advent of steam power. Notable developments included the Great Western Railway's use of paddle steamers for car ferry operations between Bristol and Ireland.

The actualization of ferries escalated rapidly with advances in steamship technology and engineering. By the late 19th century, car ferries were pivotal in connecting vast industrial regions.

Ubiquity was achieved, particularly in North America and Europe where these vessels became integrated into the transportation matrix, linking rail networks that might not have otherwise converged.

Technical and Engineering Considerations

From an engineering perspective, car ferries are marvels of ingenuity. The designs needed to account for both maritime and rail transport dynamics, necessitating robust structures to ensure seamless integration. Key features included strong, stable hulls capable of supporting heavy loads, and tracks laid directly into the deck to facilitate easy railcar movement on and off the vessel.

Several engineering challenges had to be addressed to allow for safe and efficient operation. Loading and unloading required the construction of specialized dock facilities and ramps.

Fluctuating water levels meant builders had to ensure ramps maintained alignment with the shore tracks. Thus, adaptability to tidal changes was a critical element of port and vessel design alike.

Furthermore, the ferry must ensure stability without sacrificing speed or maneuverability. Balancing these factors is crucial, as the dispersion of weight by several rail cars needs careful management to avoid capsizing risks. This has led to the deployment of multi-segment platforms and methods for distributing load over a more extensive surface area.

Geographic Reach and Impact

The North American Scene

In North America, ferries became particularly prominent. One of the quintessential examples is the SS Badger, which served the Great Lakes region, covering routes between Michigan and Wisconsin.

The Badger, as a coal-fired vessel capable of transporting entire trains, serves as a tangible remnant of the golden age of rail car ferries, connecting economic centers and enabling cross-lake rail accessibility that epitomized regional development.

It was owned by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and entered service on March 21, 1953. The Badger continued to operate in service until July 1, 1983 when then-Chessie System discontinued all car ferry services.

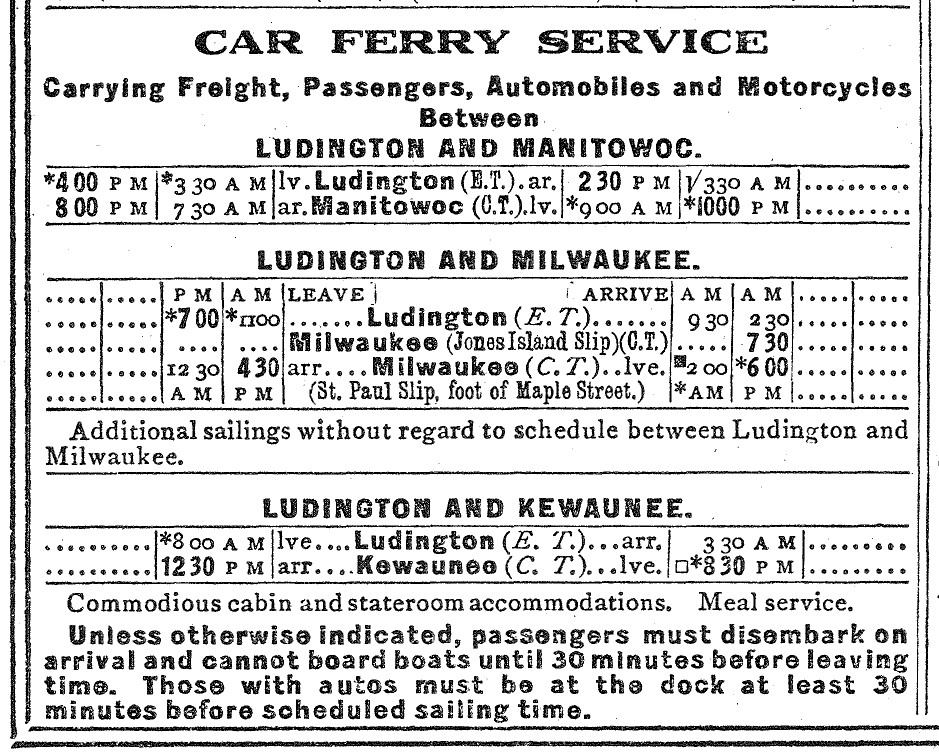

Today, it continues to run as an active museum between Ludington, Michigan, and Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The last coal-fired vessel still in service on the lakes the ferry was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 20, 2016.

Another was the S.S. Chief Wawatam which operated between Mackinaw City and St. Ignace, Michigan from 1911 until it 1984.

The East Coast witnessed the proliferation of these ferries as well, notably in New York Harbor, where they played a crucial role in bridging lines across the bustling metropolis and its surrounding areas.

This operation was an essential component of the grand tome of eastern seaboard logistics. One particularly notable company was the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal which operated expansive freight car ferries throughout New York Harbor.

European Integration

In Europe, rferries had widespread reach, particularly in Scandinavia and the British Isles. The famed "train ferries" of the late 19th and early 20th centuries connected the UK with the continent, aiding in freight transfer across strategic chokepoints like the English Channel and the Baltic Sea.

These ferries often formed part of grander national transport policies, facilitating the movement of goods within expanding empires and beyond burgeoning frontiers.

The Broader Global Context

On a wider scale, ferries also played roles beyond North America and Europe. The rail-ferry service between Japan's Hokkaido and Honshu is a prime example. These vessels allowed resource and passenger flows, critical for regional continuity, playing considerable roles in the economic knitwork of post-war Japan.

Evolution and Transition

While the golden age of railroad car ferries peaked in the early to mid-20th century, their prominence declined with the rise of faster and more versatile transportation methodologies.

The advent of containerization, improved road networks, and advancements in bridge-building technology steadily reduced reliance on traditional railway networks and their ferried extensions.

Despite this shift, some ferries have endured, primarily due to geographical or infrastructural impediments that remain insurmountable for traditional rail bridges or tunnels. These vessels are a testament to the adaptability and lasting significance of the concept.

Technology has evolved drastically; however, some locations have continued upgrading their facilities and vessels, taking advantage of modern engineering to prolong utility. The introduction of diesel-electric power sources, reinforced hulls, and automated loaing systems are among developments keeping car ferries relevant.

Environmental and Economic Implications

Economically, ferries have long been synapomorphic in maintaining vital links across water bodies, particularly in aiding trade within decentralized, transnational economies. They played a cornerstone role in local and regional economic integration, oftentimes linking remote locales to larger commercial hubs.

Continuing Relevance

The narrative of car ferries is one woven deeply into the fabric of industrialization. Despite their gradual decline from mainstream infrastructure solutions, their legacy persists in historical reverence and in some limited ongoing applications.

These ferries stand as enduring symbols of ingenuity, bridging disparate geographical regions while fostering economic exchanges that helped develop nations.

In an age where connectivity continues to drive progress, and environmental considerations increasingly dictate infrastructural approaches, the lessons learned from the evolution of railroad car ferries offer insight into balancing human mobility needs with the natural world.

They remain vivid reminders of the intersecting histories of technological advancement, commercial enterprise, and cultural narratives that define the modern age of transportation.

Recent Articles

-

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:44 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers.