Kansas City Southern Railway: Map, Photos, History

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS) was our country’s smallest Class I in the post-Staggers Act era, in terms of route miles. The Route Of The Southern Belle had always been a system surrounded by larger giants, even prior to the mega-merger movement during the classic era of the mid-20th century.

At its peak KCS operated about a 6,000-mile network, including service into Mexico, while employing more than 6,000. During its many years of operation the KCS had rocky periods although in its final years was regarded as a profitable railroad with strong leadership. Kansas City Southern formally disappeared as independent railroad on April 14, 2023.

Canadian Pacific Merger

- Alas, it became another fallen flag when Canadian Pacific announced on March 21, 2021 it would acquire the road for $25 billion (the final total was later increased to $31.6 billion.)

In the original deal (since amended), reported by Bloomberg, KCS investors were to receive 0.489 of a CP share and $90 in cash for each share they hold, valuing the stock at $275 apiece.

The new railroad became known as Canadian Pacific-Kansas City (CP-KC) with a 20,000-mile network, nearly 20,000 employees, and an annual revenue of about $8.7 billion.

Interestingly, a counterproposal by rival Canadian National nearly won the day. CN's bid of $33.6 billion to directly acquire KCS would likely have been approved by KCS shareholders.

However, the Surface Transportation Board unanimously killed the voting trust on August 31, 2021, which paved the way for the renewed CP-KCS merger. The STB approved the sale in March, 2023 and the new railroad began operations in April, 2023. -

Photos

Kansas City Southern E8A #27 has the last "Southern Belle" (Kansas City - New Orleans) near Pittsburg, Kansas on November 2, 1969. Richard Wallin photo.

Kansas City Southern E8A #27 has the last "Southern Belle" (Kansas City - New Orleans) near Pittsburg, Kansas on November 2, 1969. Richard Wallin photo.History

The Kansas City Southern's story is actually quite recent when compared to the railroad industry as a whole; the road's immediate ancestry began on January 8, 1887 with incorporation of the Kansas City Suburban Belt Railroad, promoted by Arthur Stilwell.

The terminal line served the local Kansas City region, connecting Argentine with nearby Independence via the downtown area.

In all, the KCSB utilized 40 miles of track serving packing houses, grain elevators, stockyards, and various other industries. According to the Kansas City Southern Historical Society it officially began operations on August 18, 1890.

At A Glance

856 (1930) 962 (1950) 2,995 (2000) 6,700 (2019) |

|

121 (1963) 949 (2019) |

|

581 (1963) 17,500 (2019) | |

Kansas City - Shreveport, Louisiana - Port Arthur, Texas Dallas - Shreveport - New Orleans Shreveport - Minden, Louisiana - Hope, Arkansas Minden - Alexander, Louisiana | |

Port Arthur Route Route Of The Southern Belle | |

Sources (Above Table):

- Kansas City Southern. "For The Long Haul: 2019 Sustainability Data Update." https://www.kcsouthern.com/en-us/pdf/community/kcs-2019-sustainability-report.pdf. Page 2. August 24, 2022.

- Schafer, Mike. More Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2000.

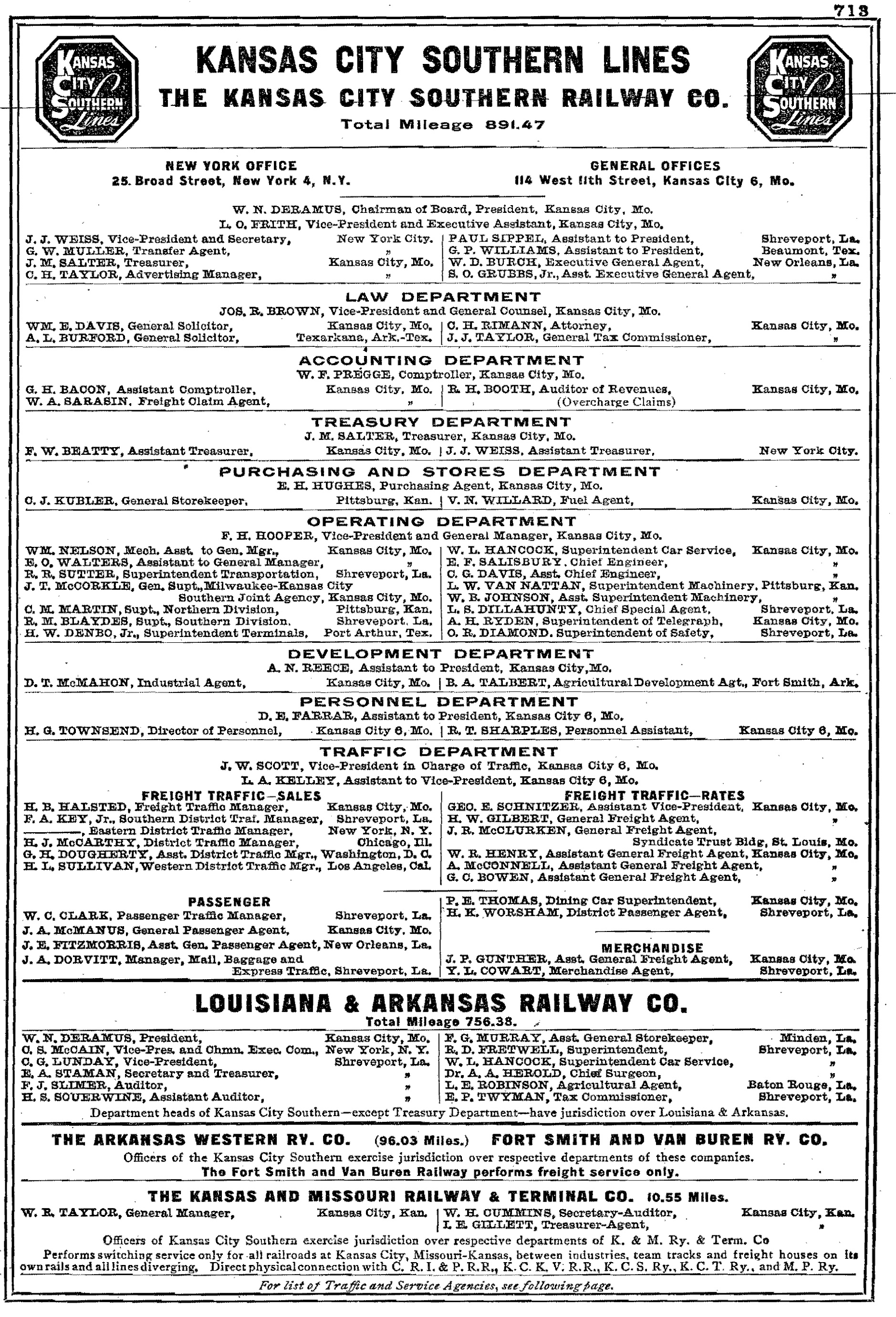

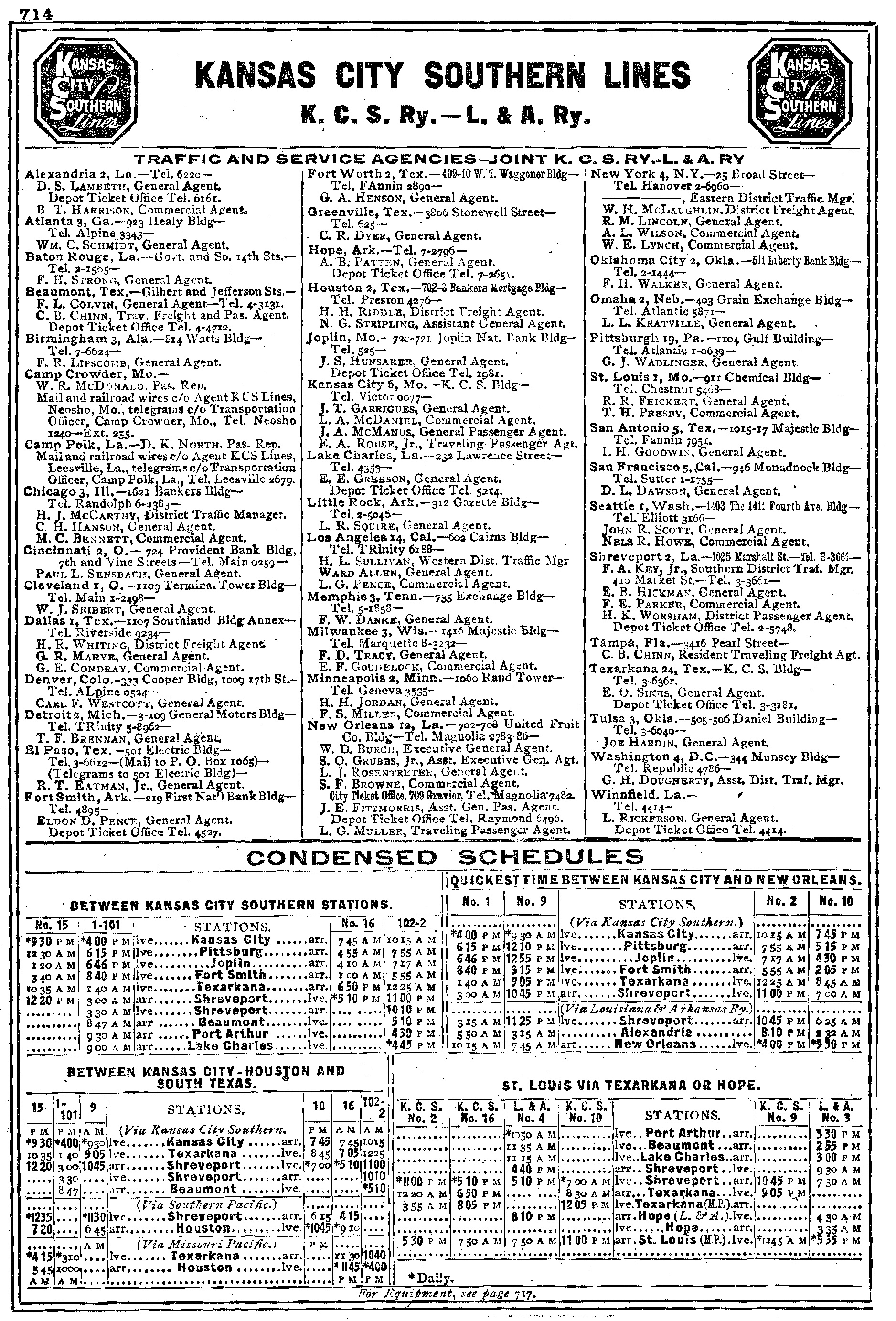

- Burns, A.J. and Burns, J.F. "Kansas City Southern Railway Company, The." Official Guide Of The Railways And Steam Navigation Lines Of The United States, Port Rico, Canada, Mexico, And Cuba, The. Volume 62. Issue 8. January, 1930. Pages 738-740.

The other early component was the Texarkana & Northern Railway. At first, this system had no actual ties to the Stilwell's operations. It had originally been chartered on June 18, 1885, intended as a logging operation that opened 10 miles from Texarkana north to the Red River.

On July 9, 1889 it changed its names as the Texarkana & Fort Smith Railway, opening an additional 16 miles to Wilton, Arkansas by 1892.

The Texas State Historical Association (TSHA) notes that year, on December 13th, the railroad was acquired by the Arkansas Construction Company, a subsidiary of Stilwell's Kansas City, Pittsburgh & Gulf Railroad.

Kansas City Southern F7A #4064 and other Fs are tied down in their typical spot behind the depot at Sulphur Springs, Texas in the summer of 1983. These were the last Fs used in freight service on a Class I. They handled lignite to TXU's coal-fired power plant in Pittsburg, which was carried to the facility by the company's own electrified railroad. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern F7A #4064 and other Fs are tied down in their typical spot behind the depot at Sulphur Springs, Texas in the summer of 1983. These were the last Fs used in freight service on a Class I. They handled lignite to TXU's coal-fired power plant in Pittsburg, which was carried to the facility by the company's own electrified railroad. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.The KCP&G had been organized on November 6, 1889 and Stilwell had plans for the railroad to provide the shortest route to the Gulf of Mexico, connecting its namesake city with the coast.

The system's purpose was two-fold; to give farmers a means of exporting their goods as well as handle imported products.

Unfortunately, this plan was never successful although not before Stilwell had completed his vision. During the Panic of 1893 the KCP&G lost its financial backing after having only reached Pittsburg, Kansas.

Logo

Undaunted, Stilwell looked anywhere for possible monetary backing to complete his project. As Mike Schafer's, "More Classic American Railroads," notes he was able to do this by garnering help through close friend George Pullman, head of the powerful Pullman Palace Car Company; together they raised $3 million in securities from Holland.

With new capital in hand, Stilwell opened coastal facilities on the Gulf at a location he named for himself, Port Arthur, Texas while "Last Spike" ceremonies were held at Beaumont on September 11, 1897.

Only two years after it all began the KCP&G fell into bankruptcy in 1899, emerging on April 1, 1900 as the Kansas City Southern Railway. The receivership forced Stilwell out and his involvement with the company ended.

As previously mentioned, his railroad's dream was not particularly successful as, even after reorganization, it struggled to earn a profit.

There was little in the way of consistent, high-volume traffic which forced the KCS to rely upon local agriculture, grain, and less-than-carload freight for most of its income. In addition, passenger traffic was thin.

As it turns out, fate had a bright future for the company when its savior came in the way of "black gold," oil. As it turns out the railroad's main line was situated right next to a discovery made near Beaumont, Texas.

In 1892 George O'Brien, George Carroll, Pattillo Higgins, Emma John, and J. F. Lanier, founded the Gladys City Oil, Gas & Manufacturing Company.

Within a few years nearly half the group had given up but in 1895 a determined Anthony Lucas signed a lease with the remaining partners, believing strongly that oil was located in the Gulf Coast's salt domes.

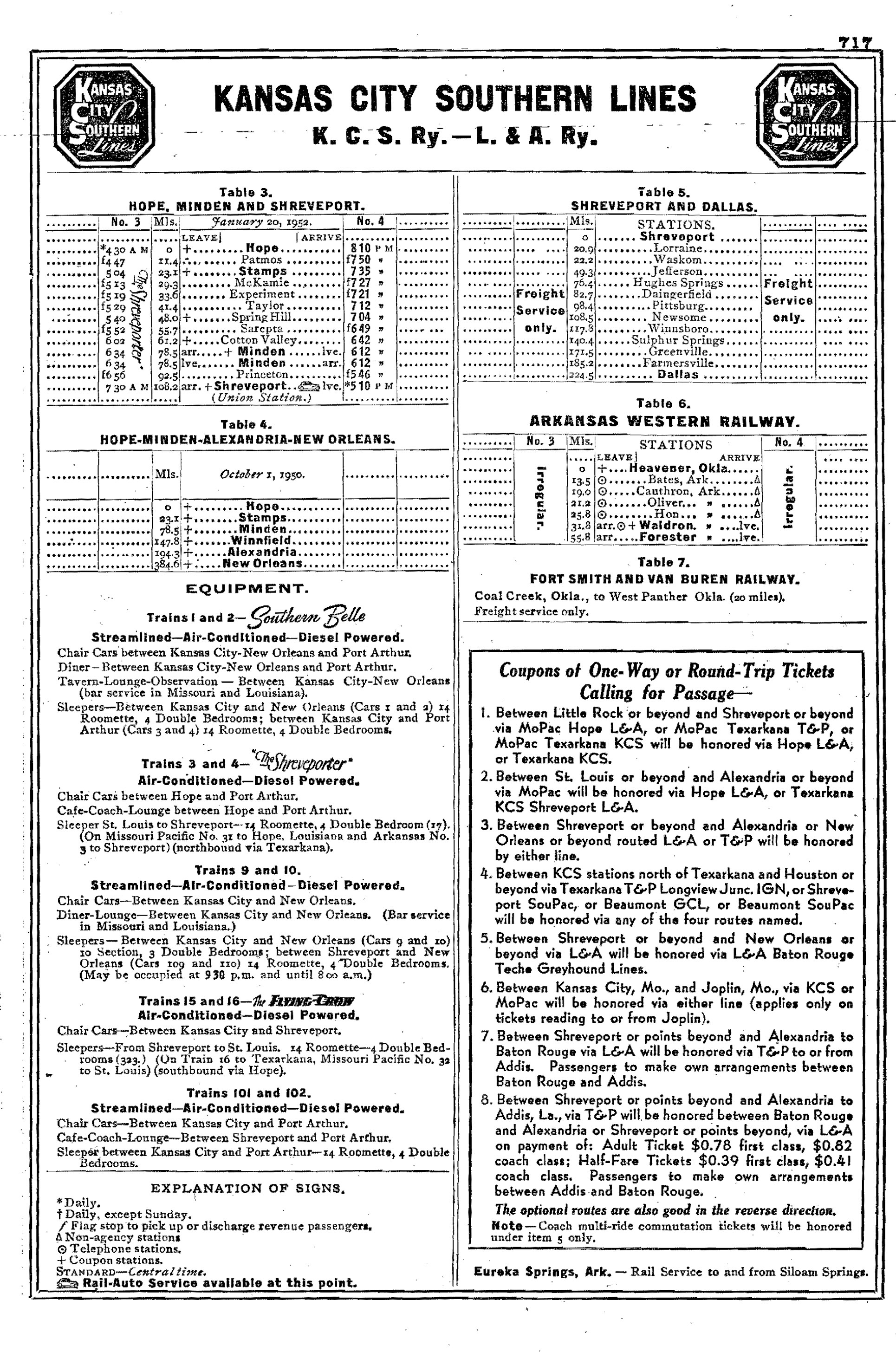

Kansas City Southern GP38-2 #4001, GP40 #777, GP38-2 #4010, and SD50 #705 lead a westbound outside of Cresson, Texas, bound for Brownwood, circa 1983. Today, this line is operated by the Fort Worth & Western. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern GP38-2 #4001, GP40 #777, GP38-2 #4010, and SD50 #705 lead a westbound outside of Cresson, Texas, bound for Brownwood, circa 1983. Today, this line is operated by the Fort Worth & Western. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.After considerable expense and effort Lucas and Hamills finally hit pay dirt. The THSA notes that on January 10, 1901, at a depth of 1,139 feet, a huge geyser of oil, 100 feet high, spilled from their well (listed as "Lucas #9") located in eastern Jefferson County, south of Beaumont.

The area became known as the Spindletop Oil Field, producing tens of thousands of barrels every day. The natural resource could not have been found at a better time as the KCS was likely headed towards another bankruptcy.

Thanks to the many uses of oil the railroad not only moved raw black gold but also gasoline and various other petrochemicals as the energy industry sprang up along the Gulf. This new traffic would account for well over one-third of the system’s profits for much of its early years (and continue to generate healthy income years).

With a newfound source of revenue, and new leadership under Leonore Fresnel Loree (1906), the KCS looked towards expansion during the 20th century.

Kansas City Southern's remaining F7s lead a long train of empty hoppers heading westbound near Sulphur Springs, Texas during December of 1981. Gary Morris photo.

Kansas City Southern's remaining F7s lead a long train of empty hoppers heading westbound near Sulphur Springs, Texas during December of 1981. Gary Morris photo.Expansion

While it took many years to see the fruits of this labor fulfilled, by the late 1930s the KCS had acquired new markets in Dallas and New Orleans. At first the railroad zeroed in on the nearby Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) and St. Louis Southwestern (Cotton Belt) railroads.

However, the Interstate Commerce Commission forced it to divest of these holdings during the 1920s. It would later pick up the Louisiana & Arkansas (second) in 1939, providing a roughly east-to-west routing from New Orleans to Dallas, Texas via Shreveport.

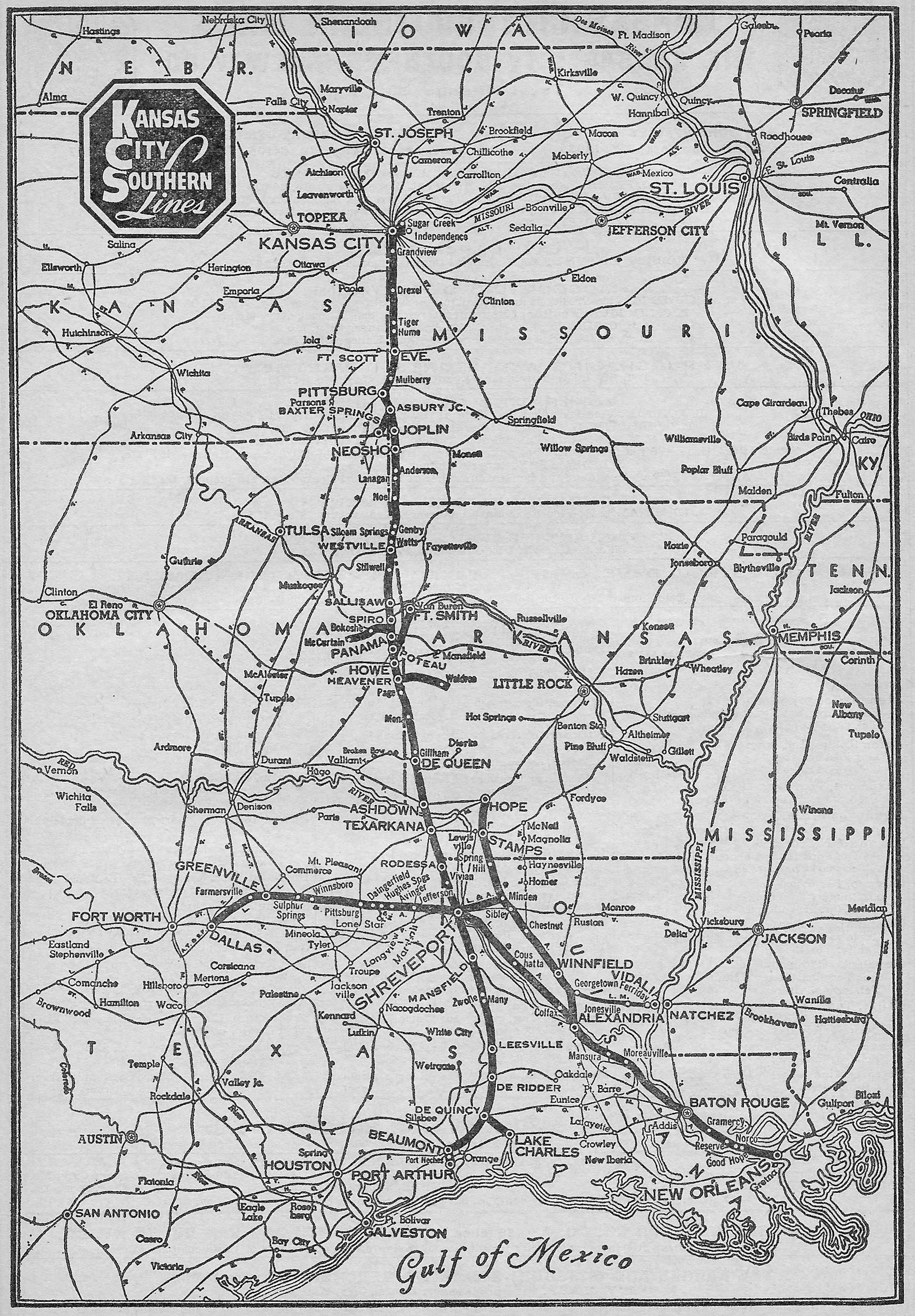

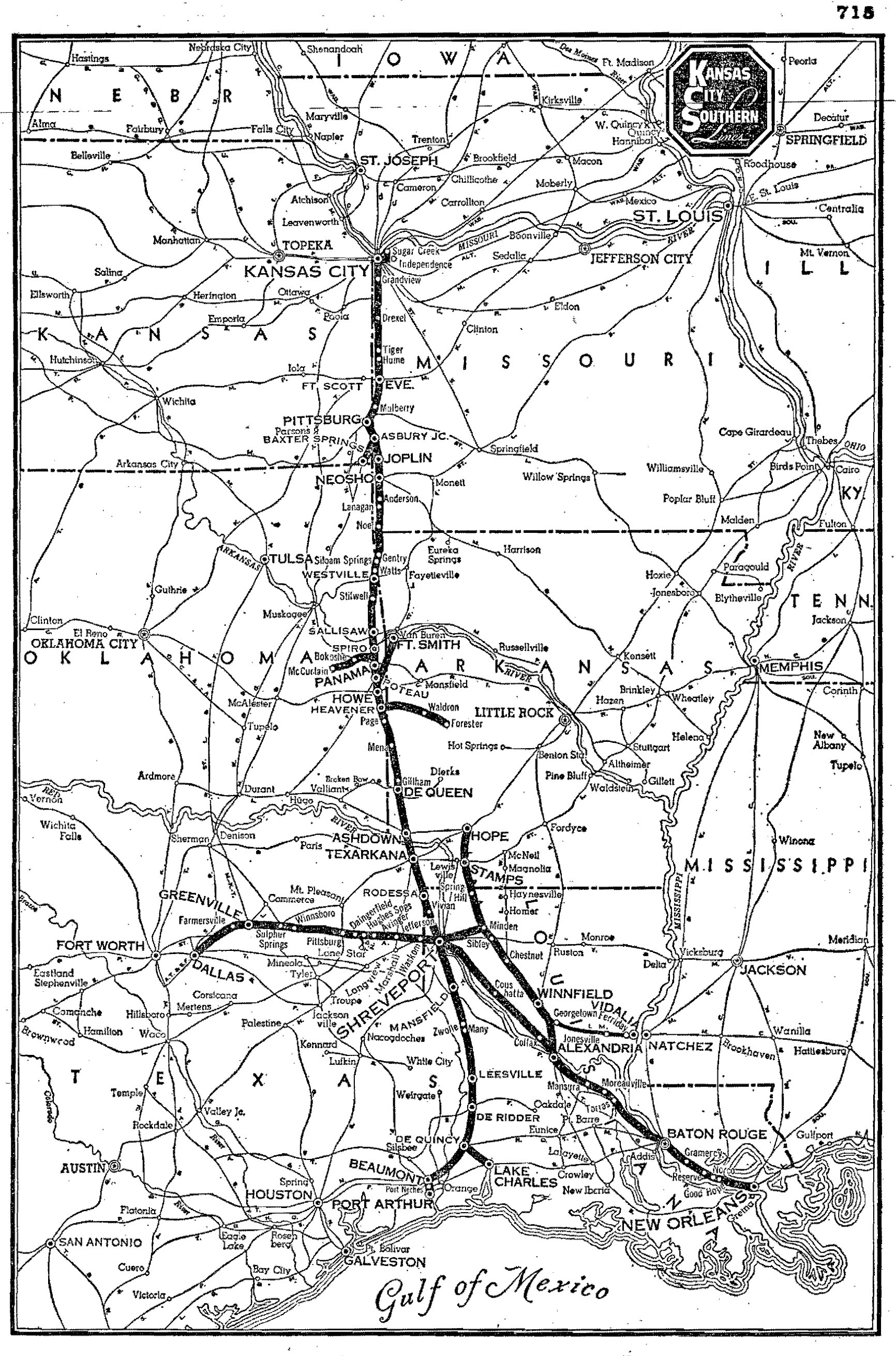

Sysytem Map

There was also an extension from Alexandria, Louisiana to Hope, Arkansas where additional interchanges were established with Missouri Pacific, Rock Island, and Cotton Belt.

The L&A was the greatest component to the historic KCS system although other minor acquisitions included the Kansas & Missouri Railway & Terminal Company (K&M), Fort Smith & Van Buren (FS&VB), Arkansas Western (AW), and the Maywood & Sugar Creek (M&SC).

By 1950, the KCS owned a network of 962 miles and had it forever remained this size would likely be only a Class II, "regional," today. For roughly the first half of the 20th century the KCS prospered, earning considerable profits for a system its size.

This was in large part due to the efforts of William Deramus who spent millions in upgrades through the 1950s by laying new ties, improving signaling for faster and more efficient operations (Centralized Traffic Control in 1943), completing dieselizing by 1953, opening the large Deramus Yard at Shreveport in 1956, and operating long freights of 200 cars or more.

After the nation's severe 1958 recession (also referred to as the Eisenhower Recession), the KCS experienced a slow and worsening decline.

It had purchased new locomotives beginning in the mid-1960s to improve operations and handle the heavier freight trains of the era; notably SD40's, SD40-2's, GP30's, and GP40-2's (road-switchers which replaced older models like the F3 and F7 cab units).

Predecessors

Fort Smith & Van Buren Railway

The FS&VB entered the KCS fold on September 30, 1939 when it was formed to acquire the Coal Creek to McCurtain, Oklahoma segment of the former Fort Smith & Western Railroad. The FS&W was chartered on January 25, 1899 and by 1903 opened from Coal Creek to Guthrie, Oklahoma via Oklahoma City.

The road struggled financially and was reorganized as the Ft. Smith & Western Railway in the early 1920s. It continued to falter into the Great Depression and finally shutdown on February 9, 1939 after which time the KCS took over the above-mentioned segment.

Graysonia, Nashville & Ashdown Railroad

The GN&A was another timber road originally chartered on June 16, 1906 as the Memphis, Paris & Gulf Railroad. Within a few years it had opened 41 miles from Ashdown, Arkansas (and a connection to the KCS) to Murfreesboro via Nashville.

On June 1, 1910 its name was changed to the Memphis, Dallas & Gulf controlled by the Graysonia & Nashville Lumber Company. On March 21, 1915 it opened between Hot Springs and Texarkana, Arkansas via Ashdown comprising a system of some 115 miles.

Unfortunately, it fell into bankruptcy a few years later and segments were sold off. On August 15, 1922 the Ashdown to Shawmut section (61 miles) became the Graysonia, Nashville & Ashdown while it further shrunk in 1926 to just a 32-mile system linking Nashville and Ashdown. The GN&A remained a small short line operation until its acquisition by KCS on July 13, 1993.

Kansas City Southern GP7 #154 at the engine terminal in Pittsburg, Kansas, circa 1967. American-Rails.com

collection.

Kansas City Southern GP7 #154 at the engine terminal in Pittsburg, Kansas, circa 1967. American-Rails.com

collection.Louisiana & Arkansas Railway

The L&A was the largest component of the historic Kansas City Southern. It was actually a merger itself of two subsidiaries, the original Louisiana & Arkansas Railway and Louisiana Railway & Navigation Company.

According to the KCSHS the earliest predecessor of the first L&A was launched by logger William Buchanan around 1896 to serve his sawmill near Stamps, Arkansas. It was one of the many, unincorporated and privately owned little railroads that could so often be found with such operations then.

On March 18, 1898 it was officially chartered as a common-carrier, the Louisiana & Arkansas Railway, as Buchanan looked to continue growing his timber holdings. Within just a few years he had built new lines or acquired others (Arkansas, Louisiana & Southern) to operate a system stretching some 273 miles between Alexandria, Louisiana and Hope, Arkansas; the former extension opened on July 1, 1906 while the latter was reached on June 1 1903.

A few years later, on July 1, 1910, the L&A reached Shreveport, Louisiana thanks to its acquisition of the Minden East & West Railroad (via Minden). During Kansas City Southern's, Harvey Couch era, he acquired control of the L&A and LR&N on January 16, 1928. Later that year, on July 7th he formed a second Louisiana & Arkansas Railway Company combining both into the new L&A on May 8, 1929.

Kansas City Southern GP7 #4156 at Heavener, Oklahoma, circa 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern GP7 #4156 at Heavener, Oklahoma, circa 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Louisiana Railway & Navigation Company

The LR&N's earliest predecessor was the Shreveport & Red River Valley Railroad, a project started by William Edenborn in 1896 to connect Shreveport with New Orleans.

The first segment opened between Shreveport and Coushatta, Louisiana on October 1, 1898 and reached as far south as Mansura by September of 1902.

At this time the system was reorganized as the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Company on May 9, 1903, opening to New Orleans on April 14, 1907. The LR&N continued to expand following the completion of its original main line.

Looking to the west it acquired a former branch of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad ("The Katy") between McKinney, Texas and the Louisiana state line (near Waskom, Texas) on April 1, 1923.

To provide service on this disconnected segment the LR&N acquired trackage rights over the Texas & Pacific (Missouri Pacific) west of Shreveport. The line to Dallas became a very important component of the KCS system and still witnesses considerable use today.

Kansas City Southern's business train at Houston Union Station in October of 1996. Today, the Houston Astros' Minute Maid Park occupies this location. Gary Morris photo.

Kansas City Southern's business train at Houston Union Station in October of 1996. Today, the Houston Astros' Minute Maid Park occupies this location. Gary Morris photo.However, it began a program of deferred maintenance in the 1960s to offset the slow period, which produced a better bottom line. Unfortunately, such tactics are only "successful" for short periods and can have long-lasting, very negative, effects if carried out over many years.

This turned out to be the case for KCS; with top management too focused on other things the railroad's physical plant slipped into a decaying state of repair and it all came to head in late 1972. With worn out ties and the road's infrastructure unable to bear the weight of multi-ton trains, derailments occurred one after another.

If it were not for record volumes of traffic the railroad could have faced a fatal problem, similar to its northern neighbor the Rock Island. While deferred maintenance offers short term relief for a railroad's bottom line in the long term it can cost substantially more to alleviate as the KCS found out.

A trio of new Kansas City Southern SD40's, including #605 and #602, are seen here in Pittsburg, Kansas, in the summer of 1967. American-Rails.com collection.

A trio of new Kansas City Southern SD40's, including #605 and #602, are seen here in Pittsburg, Kansas, in the summer of 1967. American-Rails.com collection.Under the direction of new president Thomas S. Carter in 1973, who replaced Deramus's son (William N. Deramus III), the modern day KCS system began to take shape.

He spent millions to improve the company's physical degradation although things got worse before they got better; Mr. Schafer notes that 1974 cost the railroad $2 million in damages via 41 derailments.

Thankfully, with plenty of traffic to keep the railroad stable (coal and petrochemicals in particular) it began to pull out of the mess and the 1980s were a prosperous period.

Into the 1990s and early 2000s numerous acquisitions saw the railroad grow substantially, expanding six-fold over its historic size.

The first occurred on January 1, 1994 when it formerly took over MidSouth Rail Corporation, a 1,212-mile regional that had launched operations on March 31, 1986 utilizing former Illinois Central and Gulf, Mobile & Ohio trackage.

The lines ran east of Shreveport to Jackson and Meridian, Mississippi before turning north into Counce, Tennessee. In addition, there was access to Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama as well as Gulfport, Mississippi.

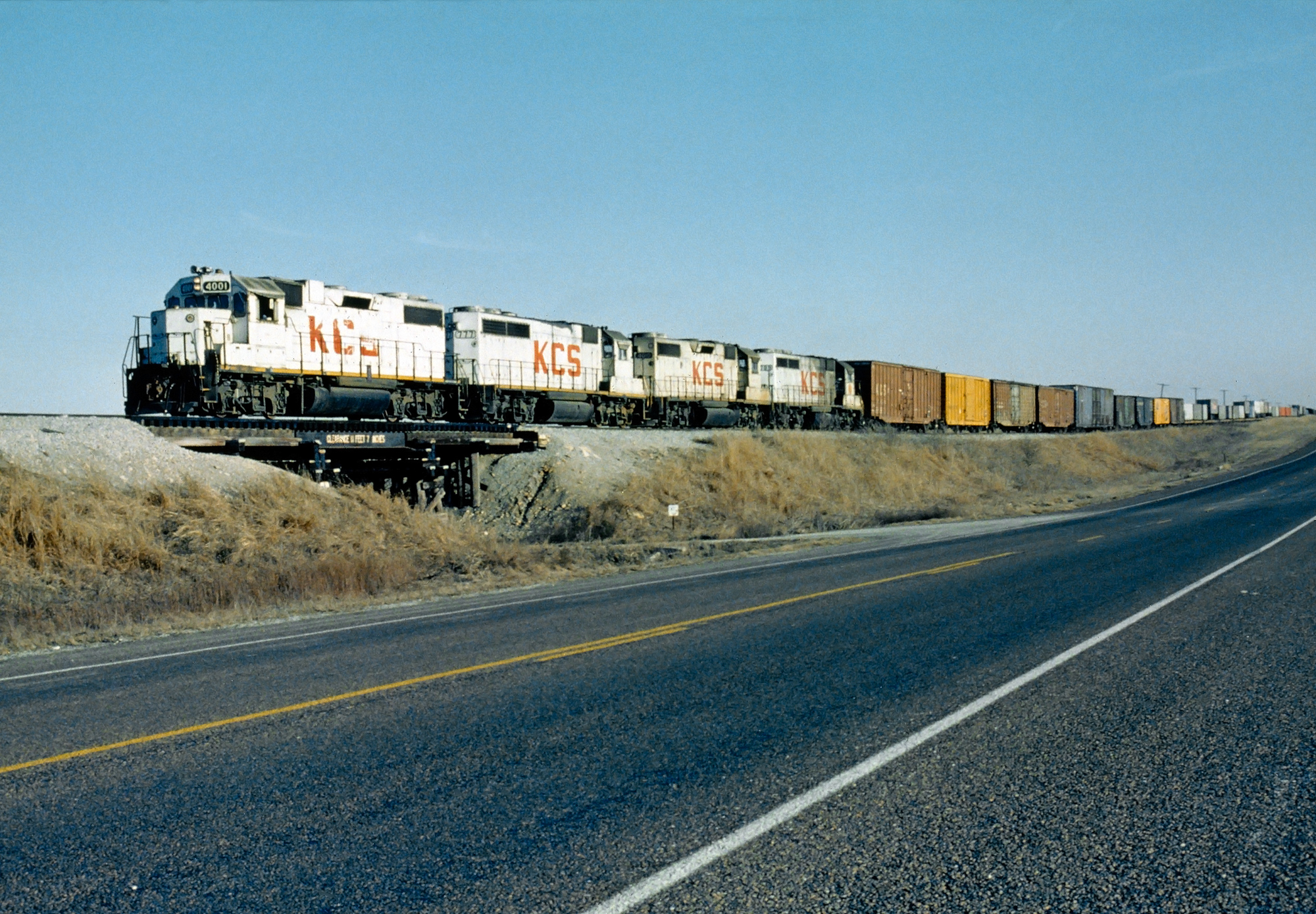

Kansas City Southern F3A #95 lays over in Kansas City, circa, 1977. Mac Owen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern F3A #95 lays over in Kansas City, circa, 1977. Mac Owen photo. American-Rails.com collection.The second significant addition was the purchase of Gateway Western (and its subsidiary, Gateway Eastern) in May of 1997. This large regional began service on January 9, 1990.

The GWWR was itself a new startup for the defunct Chicago, Missouri & Western Railway, launched on April 28, 1987 over yet more former Illinois Central Gulf trackage.

The ICG had spent the mid-1980s selling off large chunks of its network in an attempt to reverse its sagging financial condition.

The CM&W operated much of the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio's former main line between Chicago and St. Louis, as well as the corridor between Kansas City and Springfield. In all, it totaled some 633 miles. However, within a year the company was in bankruptcy.

On January 9, 1990 the new Gateway Western Railway was formed by a New York investment firm, acquiring the 408 miles from St. Louis to Kansas City via Springfield while the remainder into Chicago was purchased by Southern Pacific.

The GWWR became successful in part due to the Santa Fe, which utilized trackage rights to reach St. Louis (until the Burlington Northern Santa Fe merger of 1995).

An aging Kansas City Southern E8A, #25, was photographed here by Robert Eastwood, Jr. at the engine terminal in Pittsburg, Kansas, circa 1968. American-Rails.com collection.

An aging Kansas City Southern E8A, #25, was photographed here by Robert Eastwood, Jr. at the engine terminal in Pittsburg, Kansas, circa 1968. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Trains

While the KCS was never a big player in the passenger market, like several other roads it did have a few notable trains such as the Southern Belle streamliner which operated between Kansas City and New Orleans.

Adorned in an eye-catching Brunswick Green (which appears almost black), yellow, and red the train operated between 1940 and late 1969 until hard times and a weakening passenger market forced its cancellation.

Flying Crow: (Kansas City - New Orleans/Port Arthur)

Shreveporter: (Hope - Shreveport)

Southern Belle: (Kansas City - New Orleans)

Kansas City Southern S-12 #1160 lays over in Kansas City, circa 1965. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern S-12 #1160 lays over in Kansas City, circa 1965. American-Rails.com collection.At about the same time of the aforementioned takeovers, KCS was able to gain complete control of two railroads near, or within Mexico; the Texas Mexican Railway (a southern Texas road that linked with the Mexican border) and Grupo Transportación Ferroviaria Mexicana (TFM).

While the KCS, itself, was only about 3,100 miles in length thanks to acquisitions of Tex Mex and TFM (Kansas City Southern de Mexico), which added about 2,800 miles to its overall system, the railroad boasted a roughly 6,000-mile network.

This trackage still paled in comparison to the other six North American Class Is: Union Pacific and BNSF both maintain about 32,000 miles; CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern roughly 21,000 miles; Canadian National 20,000 miles; and Canadian Pacific 14,000 miles.

As a result, it was only a matter of time before one of these larger systems acquired the road, which finally occurred with Canadian Pacific's March, 2021 announcement.

Kansas City Southern's logo was unchanged throughout its corporate existence while it featured a number of different paint schemes over the years ranging from whites, reds, blacks, and grays to its switch back to the classic Southern Belle scheme of Brunswick Green, yellow, and red during the mid-2000's.

Kansas City Southern GP30 #115 and F7A #93 (ex-#76D) layover at the engine terminal in Shreveport, Louisiana on March 9, 1969. Tom Hoffmann photographs, Rick Burn collection.

Kansas City Southern GP30 #115 and F7A #93 (ex-#76D) layover at the engine terminal in Shreveport, Louisiana on March 9, 1969. Tom Hoffmann photographs, Rick Burn collection.Diesel Roster

Electro-Motive

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3A | 1-3 | 1938-1939 | 3 |

| E6A | 4-5 | 1942 | 2 |

| E9A | 25 | 1959 | 1 |

| E8A | 26-29 | 1952 | 4 |

| F3A | 30A-31A, 50A-59A, 50D-58D | 1947-1948 | 21 |

| F3B | 30B-31B, 50B-58B, 50C-58C | 1947-1948 | 20 |

| F7A | 32A-33A, 59D, 70A-76A, 72D-76D | 1949-1950 | 15 |

| F7B | 32B-33B, 70B-79B, 72C-78C | 1949-1950 | 17 |

| F9A | 32A, 58D, 74D | 1955-1956 | 3 |

| GP30 | 100-119 | 1962-1963 | 20 |

| GP7 | 150-162 | 1951-1953 | 13 |

| GP9 | 163-165 | 1959 | 3 |

| SD40 | 600-636 | 1966-1971 | 37 |

| SD40-2 | 637-692 | 1972-1980 | 56 |

| SD40X | 700-703 | 1979 | 4 |

| SD50 | 704-713 | 1981 | 10 |

| SD60 | 714-759 | 1989-1991 | 46 |

| GP40-2 | 796-799 | 1979-1981 | 4 |

| NW2 | 1100-1102, 1200-1229 | 1939-1949 | 30 |

| SW7 | 1300-1315 | 1950-1951 | 16 |

| SW1500 | 1500-1541 | 1966-1972 | 42 |

| GP38-2 | 4000-4011 | 1974-1978 | 12 |

| SD70ACe | 4000-4059 (Latest Numbering), 4100-4129 | 2005-2008 | 90 |

| MP15DC | 4363-4366 | 1975 | 4 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES44AC | 4650-4759 | 2007-2008 | 110 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| D-25 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| E (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| F-2 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| G | Articulated | 0-6-6-0 |

| G-2 | Articulated | 2-8-8-0 |

| H (Various) | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| J | Texas | 2-10-4 |

| K, K-1, K-21 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| L, L-1 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| M-22 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| S | Shay | 0-4-4-4-0T |

Kansas City Southern MP15DC #4365 is seen here at work near the shops at Deramus Yard in Shreveport, Louisiana, circa 1983. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Kansas City Southern MP15DC #4365 is seen here at work near the shops at Deramus Yard in Shreveport, Louisiana, circa 1983. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Macaroni Line

The last mileage KCS added was the resurrection of 87.5 miles of former Southern Pacific trackage between Victoria and Rosenberg, Texas, which Trains Magazine reported began service on June 18, 2009.

Also known as the "Macaroni Line" this property came under SP control around 1885 and remained in use until 1985, after which time the trackage was largely pulled up but the right-of-way remained under railroad ownership.

It fell under Union Pacific's jurisdiction after its 1996 takeover of SP and subsequently purchased by Kansas City Southern in 2001. The railroad began first clearing the right-of-way for rehabilitation in 2007 and had it ready for service within a few years.

The new corridor was a vital link to the KCS lines in Mexico and allowed it to discontinue a circuitous 161-mile routing of trackage rights over UP. Today, it sees considerable use and is fully monitored by Centralized Traffic Control (CTC).

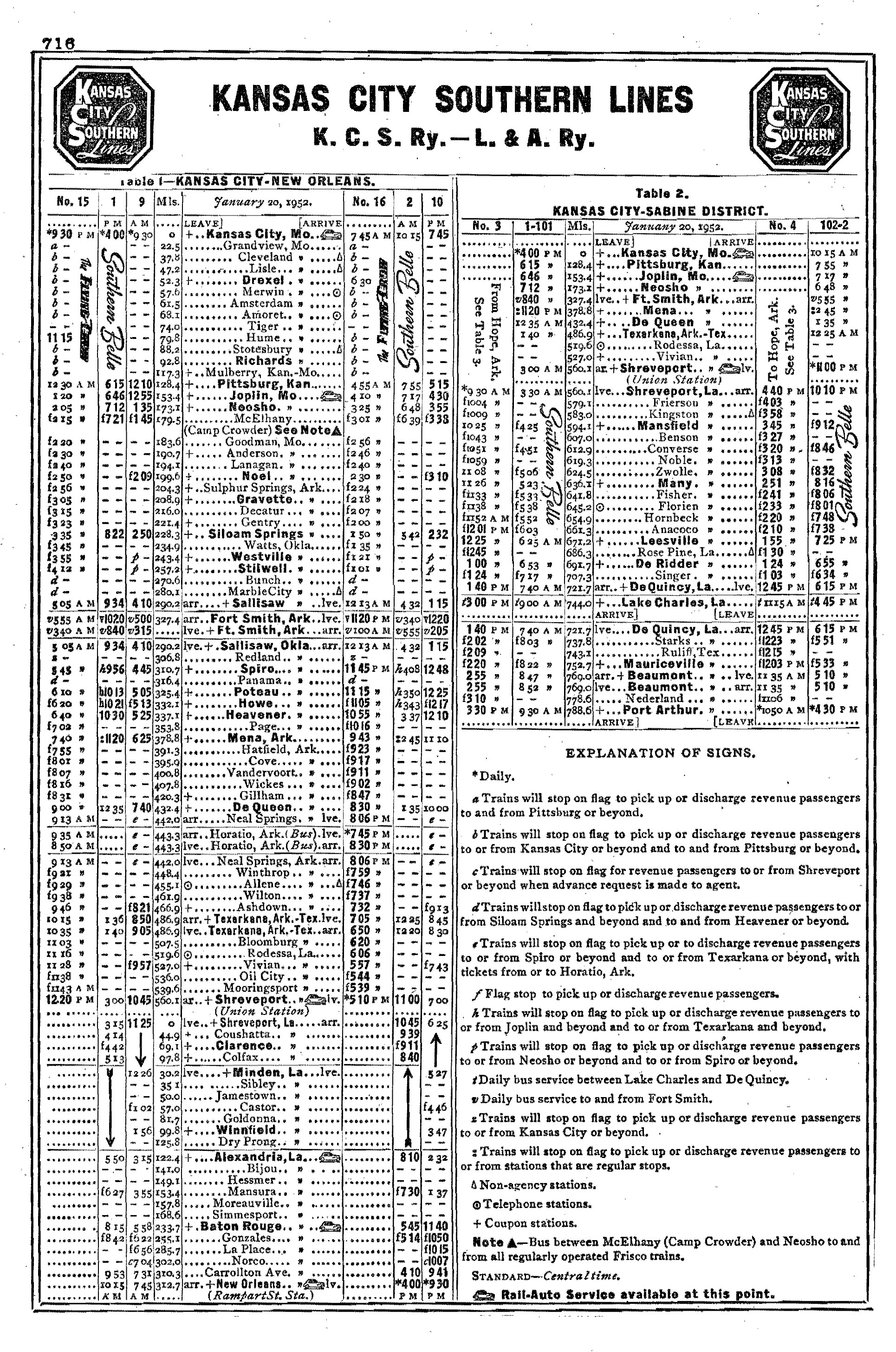

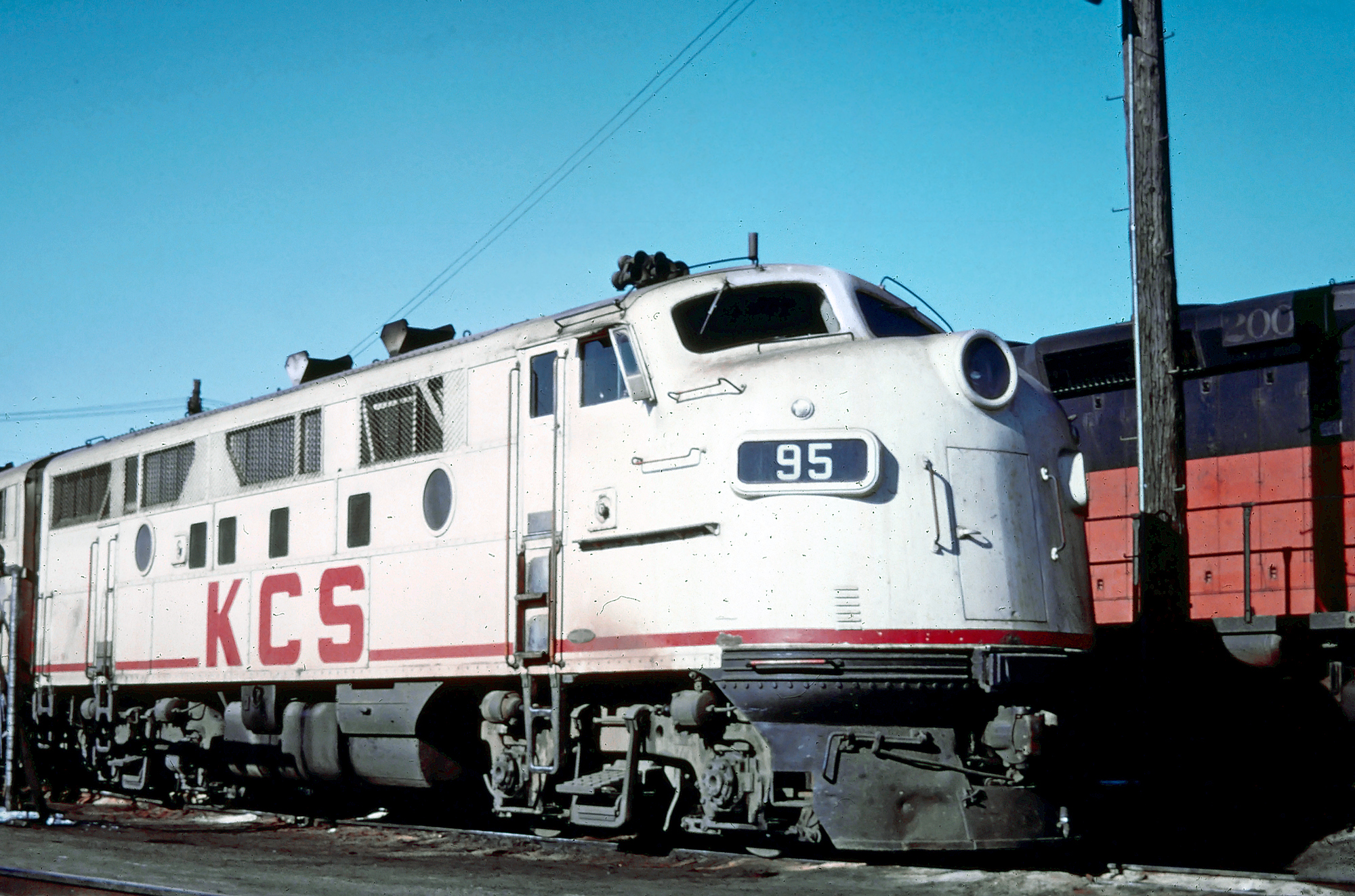

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Additional Sources

- Boyd, Jim. Kansas City Southern, In Color: The Era Of Streamlined Hospitality, 1940-1970. Scotch Plains: Morning Sun Books, 2003.

Recent Articles

-

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail.