Lehigh Valley Railroad: Map, Roster, Logo, History

Last revised: October 25, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Lehigh Valley Railroad was another of the many Northeastern carriers built to move anthracite coal from eastern Pennsylvania.

So, its motto, Route Of The Black Diamond, was quite befitting and led directly to both its rise in prosperity and downfall into bankruptcy.

The LV has also gained quite a following by those who study the industry; it utilized an interesting variety of paint schemes while providing services ranging from rural branch lines to hotshot, time freights. Unfortunately, the LV lived a roller-coaster existence throughout the 20th century.

The Great Depression hit the company particularly hard and it struggled to make ends meet after World II, postings its last profits during the 1950s.

It was one of the numerous bankrupts rolled into Conrail whereupon its routes were considered superfluous. Today, much of the LV is but overgrown paths and walking trails; a sad end to one of the Northeast's most fascinating railroads.

Photos

A pair of rebuilt FA-2's are seen here at Lehigh Valley's terminal in Sayre, Pennsylvania during late August of 1959. As a rebuilt locomotive, FA-2 #582 became the last such unit manufactured by Alco. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of rebuilt FA-2's are seen here at Lehigh Valley's terminal in Sayre, Pennsylvania during late August of 1959. As a rebuilt locomotive, FA-2 #582 became the last such unit manufactured by Alco. American-Rails.com collection.History

The Lehigh Valley can trace its heritage back to northeastern Pennsylvania and the great Anthracite coal rush that began with the Lehigh Coal Mine Company in 1792 and expanded during the War of 1812.

Once this very hard, clean-burning product was discovered many individuals put projects into motion for its transportation to the Northeast's great metropolitan regions as a source of heating fuel.

Two of the earliest successful ventures were the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company of 1822 and the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company of 1823 (later the Delaware & Hudson Railway).

The direct predecessor of the Lehigh Valley was the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill & Susquehanna Railroad incorporated on September 20, 1847.

It was projected to run in direct competition against the successful LC&N (under the guidance of Josiah White), which operated mines near Summit Hill, Pennsylvania.

From there the anthracite was moved down the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers (later operated as part of the Lehigh and Delaware Canals) via barge to Philadelphia.

At A Glance

1,361.75 (1930) 1,254 (1950) | |

Jersey City - Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania - Buffalo/Niagara Falls, New York Mountain Top - Avoca - Pittston Junction, Pennsylvania Sayre, Pennsylvania - Fair Haven, New York Van Etten - Ithaca - Geneva, New York Geneva - Auburn, New York Ithaca - Canastota, New York Rochester - Hemlock, New York Sayre - Elmira, New York Penn Haven Junction - Hazleton - Mt. Carmel, Pennsylvania Towanda - Bernice, Pennsylvania South Plainfield - Perth Amboy, New Jersey | |

Freight Cars: 10,835 Passenger Cars: 0 | |

Unfortunately, the DLS&S was having difficulty raising capital, in part due to the efforts of the LC&N. Its fortunes finally turned when Asa Packer breathed new life into the operation.

Packer carried the vision to see much of the Lehigh Valley system in place before he passed away on May 17, 1879. He was born on December 29, 1805 in Mystic, Connecticut and spent his early life as a carpenter and eventually settled in Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania (now known as Jim Thorpe), along with his wife, Sarah.

Packer became a successful operator and builder of canal boats for the LC&N, a strange twist for an individual who later earned his wealth in the railroad industry.

Using his financial success, and with the help of investors, he acquired the DLS&S charter and renamed it as the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1853.

What was once a sputtering idea now wasted no time constructing a 45.7-mile line from Mauch Chunk to Easton; according to Mike Schafer's book, "More Classic American Railroads," the route officially opened for service on September 12, 1855.

Logo

Initially, the southern terminus of Easton meant coal would once more require a transfer to barges and either travel down the Delaware River to Philadelphia or cross the waterway for shipment east towards New York.

That changed once a bridge was completed into Phillipsburg, New Jersey. The Easton/Phillipsburg area remained an important interchange location where the LV; Central Railroad of New Jersey; Lehigh & Hudson River; Pennsylvania (Bel-Del Division); and Delaware, Lackawanna & Western all met.

Lehigh Valley PA-1 #604 heads off to the scrapper as it departs Sayre, Pennsylvania behind an SW1 on October 4, 1963. Photographer unknown. Author's collection.

Lehigh Valley PA-1 #604 heads off to the scrapper as it departs Sayre, Pennsylvania behind an SW1 on October 4, 1963. Photographer unknown. Author's collection.Expansion

Packer's system now held an all-rail route into the Northeast's metropolitan regions and spent the next several years eyeing western growth. In 1864 his railroad opened 23 miles above Mauch Chunk to White Haven and then acquired the moribund Beaver Meadows Railroad & Coal Company.

This little system was originally chartered on April 7, 1830 to serve mines near Beaver Meadows, Pennsylvania for the transportation of coal to Easton. Its plan was similar to the LV's but its promoters' hopes never made it beyond a bit of grading work.

A pair of Lehigh Valley GP38-2's layover between assignments on Thanksgiving Day (November 23rd), 1972 at Newark, New Jersey. Max Robin photo.

A pair of Lehigh Valley GP38-2's layover between assignments on Thanksgiving Day (November 23rd), 1972 at Newark, New Jersey. Max Robin photo.Passenger Trains

The LV had a modest passenger train fleet with its most notable service the flagship Black Diamond. In the hotly contested New York - Buffalo market, the road had difficulty remaining competitive operating a route that tended to be slower than its surrounding counterparts.

With its financial fortunes in steep decline, the LV was success in canceling all passenger services by 1961.

The Black Diamond: (New York - Buffalo)

Maple Leaf: (New York - Toronto)

The Star: (New York - Buffalo)

Asa Packer: (New York - Pittston/Hazleton)

The John Wilkes: (New York - Pittston/Hazleton)

Lehigh Valley RS2 #217 (built as Chesapeake & Ohio #5500) is seen here in Buffalo, New York circa 1976.

Lehigh Valley RS2 #217 (built as Chesapeake & Ohio #5500) is seen here in Buffalo, New York circa 1976.The LV used the old charter to tap more mines as it opened similar branches throughout eastern Pennsylvania. Packer's name may not be remembered as widely as Vanderbilt, Huntington, or Gould but he was a true visionary and adept businessmen who worked hard to transform his railroad into one of the Northeast's largest.

As he continued pushing rails westward a segment of an old canal operation was acquired, known as the North Branch Division of the Pennsylvania Canal (or North Branch Canal), in 1866.

Lehigh Valley PA-1 #604 is seen here stopped at Bethlehem Union Station during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Lehigh Valley PA-1 #604 is seen here stopped at Bethlehem Union Station during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.This system had been built between 1828 and 1856 with an entire length of 169 miles; it ran from Northumberland to Wilkes-Barre before turning north to the New York state line via Towanda and Sayre (the location of LV's primary shops and maintenance facilities).

It utilized the segment north of Wilkes-Barre, a town it had reached via new construction at around the same time. Railroads in development during this period were quick acquire former canal rights-of-way when available as their accompanying towpaths offered a superb, "water-level" gradient that carried few curves.

Lehigh Valley FA-2 #594 was photographed here at Niagara Falls, New York on August 22, 1964. Harry Juday photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Lehigh Valley FA-2 #594 was photographed here at Niagara Falls, New York on August 22, 1964. Harry Juday photo. American-Rails.com collection.Packer renamed the property as the New York & Pennsylvania, extending service to the state line at Waverly, New York in 1869 where it interchanged with the New York & Erie (Erie).

The NY&E provided an east-west routing across its home state and was once the longest railroad in the country when opened in 1851.

The system had been designed to 6-foot, "broad gauge" (or "Erie gauge" as it liked to say) believing that it held advantages in safety, increased tonnage, and as a deterrent against interchange.

As the gauge of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches became the popular choice the NY&E later dropped its 6-foot width in favor of the industry standard.

Through the Waverly connection the LV now had an all-rail outlet to Buffalo. This agreement certainly helped and aided in the road's growth although Packer sought his own, direct routing into Buffalo.

Unfortunately, LV's founder did not live long enough to see this dream realized although he did lay the foundation by acquiring the Geneva, Ithaca & Sayre Railroad in 1876. This road, started by Ezra Cornell, gave the LV access to Geneva while the line was finally extended into Buffalo during 1892.

Lehigh Valley GP38AC #310 pulls the Delaware & Hudson's pair of RF16 "Sharks" and their train into the LV's terminal at Sayre, Pennsylvania in August of 1975. Since the D&H freight had operated over the Erie Lackawanna's main line they arrived at the yard's west end and were thus forced to runaround their train as noted by the caboose now being on the head-end. The RF16s still survive as the only two in existence, stored away indoors on short line Escanaba & Lake Superior in Michigan. Jerry Custer photo.

Lehigh Valley GP38AC #310 pulls the Delaware & Hudson's pair of RF16 "Sharks" and their train into the LV's terminal at Sayre, Pennsylvania in August of 1975. Since the D&H freight had operated over the Erie Lackawanna's main line they arrived at the yard's west end and were thus forced to runaround their train as noted by the caboose now being on the head-end. The RF16s still survive as the only two in existence, stored away indoors on short line Escanaba & Lake Superior in Michigan. Jerry Custer photo.Could The LV Have Survived To The Modern Day?

It is unlikely the Lehigh Valley could have survived into the modern era. The LV competed against several carriers in its territory, notably the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western and Erie, both of whom also reached Buffalo, while the latter continued on to Chicago.

The Windy City was the ultimate nexus for eastern carriers, albeit only four systems ever extended that far west (Erie, Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York Central).

The LV tried to diversify its traffic base after World War II but the road was built to handle coal and even had trouble competing against the Lackawanna, a well-managed system with a very competitive route of its own.

Unlike the DL&W, however, the LV was not burdened by extensive commuter operations. Alas, the LV was superfluous by the 1970s and coupled with its heavy debt likely would have been liquidated if not for its inclusion into Conrail.

That being said, strict government regulations, which plagued the entire industry, certainly aided in its downfall. The entire Northeast would not have been in such a dire situation by the 1970s had deregulation been implemented years earlier.

Lehigh Valley 2-8-2 #425 (N-4) is seen here at work under the signal bridge in Easton, Pennsylvania during the fall of 1948. John Maris photo.

Lehigh Valley 2-8-2 #425 (N-4) is seen here at work under the signal bridge in Easton, Pennsylvania during the fall of 1948. John Maris photo.There is a chance the LV could have survived if it had been included as part of initial efforts to create more competition against Conrail.

As planners at the United States Railway Administration worked to put together the conglomerate there were many proposals aimed at providing the Port of New York with at least two railroads and as many as three.

One idea involved merging the LV, Reading, CNJ, and Erie Lackawanna into a secondary giant as a Conrail competitor while another theory proposed having the profitable N&W and Chessie System (C&O, B&O, and Western Maryland) acquire segments of the Reading (B&O) and EL (N&W) to reach New York with government subsidies/loans as an incentive.

Unfortunately, the solvent roads were wary of potentially dragging their own companies into bankruptcy while the government was unwilling to fund two giant systems believing the region was already saturated with too much trackage. However, had this occurred more of the LV may have remained in service than what was utilized under Conrail.

Lehigh Valley GP38-2s, just a few months old, pause with their train at the Sayre terminal on February 4, 1973. Carl Sturner photo.

Lehigh Valley GP38-2s, just a few months old, pause with their train at the Sayre terminal on February 4, 1973. Carl Sturner photo.Before Asa Packer died he also laid the groundwork for LV's extension beyond the New Jersey state line. For many years it had relied upon interchange connections but as rail competition to the Port of New York intensified it realized it needed its own route.

It all began when Packer created the Easton & Amboy Railroad in 1872, which acquired the former charter of the Perth Amboy & Bound Brook Railroad, authorized to develop port facilities at Perth Amboy, New Jersey.

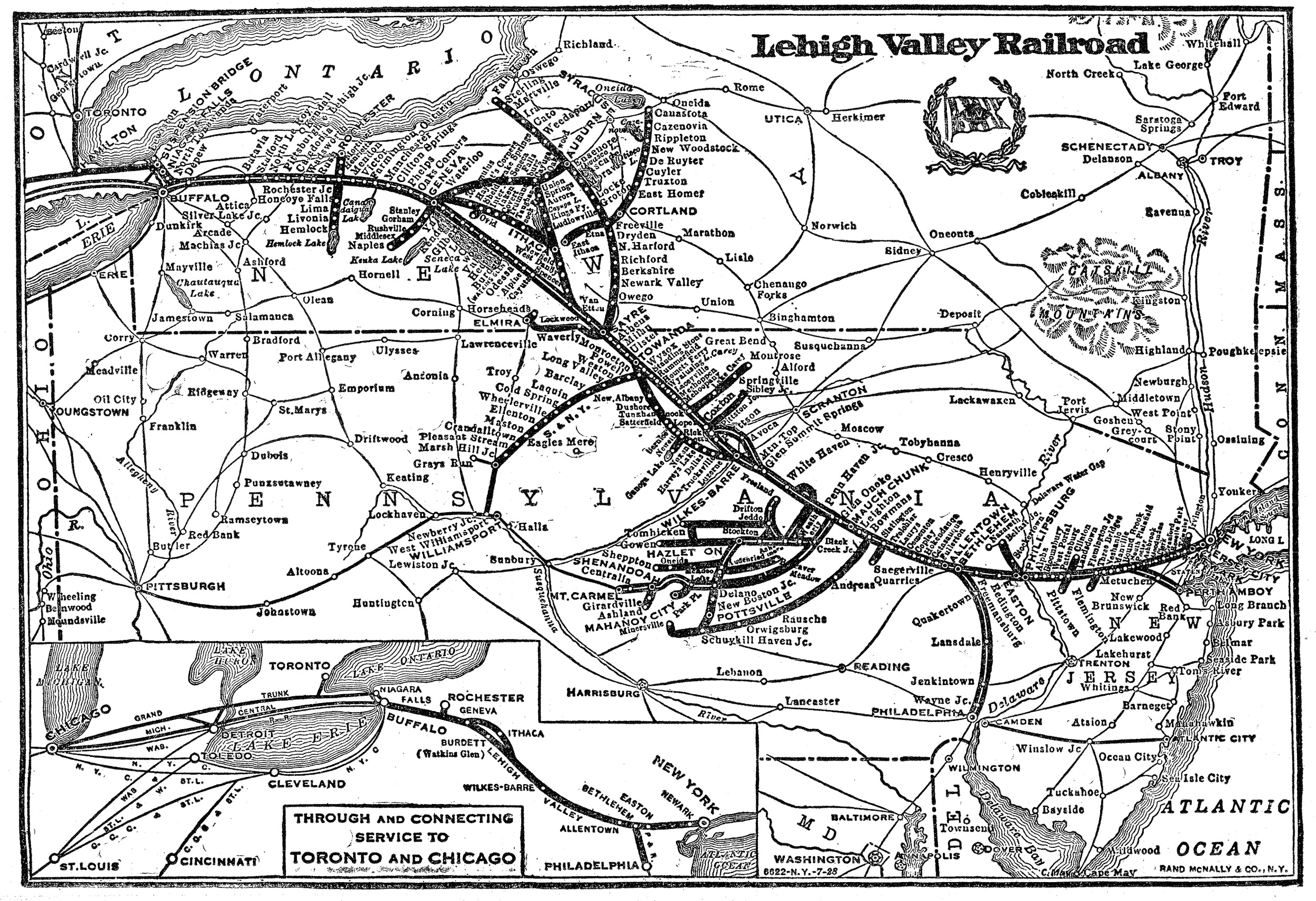

System Map (1940)

Following the completion of the Pattenburg Tunnel the 60-mile corridor, running via Easton/Phillipsburg, officially opened on May 28, 1875.

Perth Amboy remained an important terminus for the Lehigh Valley throughout the years although its southerly location placed it a bit too far south of New York. So, the railroad embarked on a northerly extension to the western shore of the Hudson River at Jersey City.

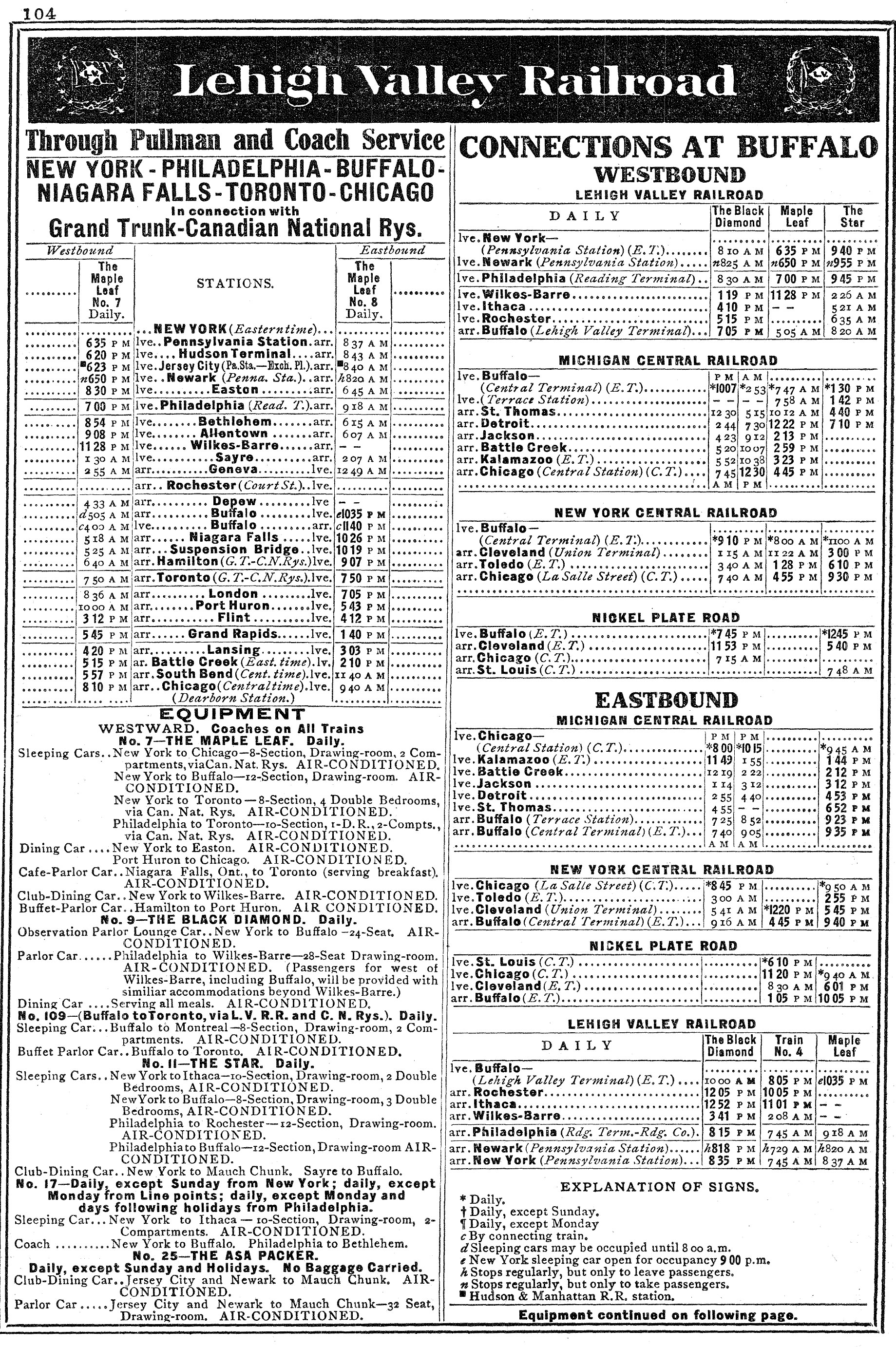

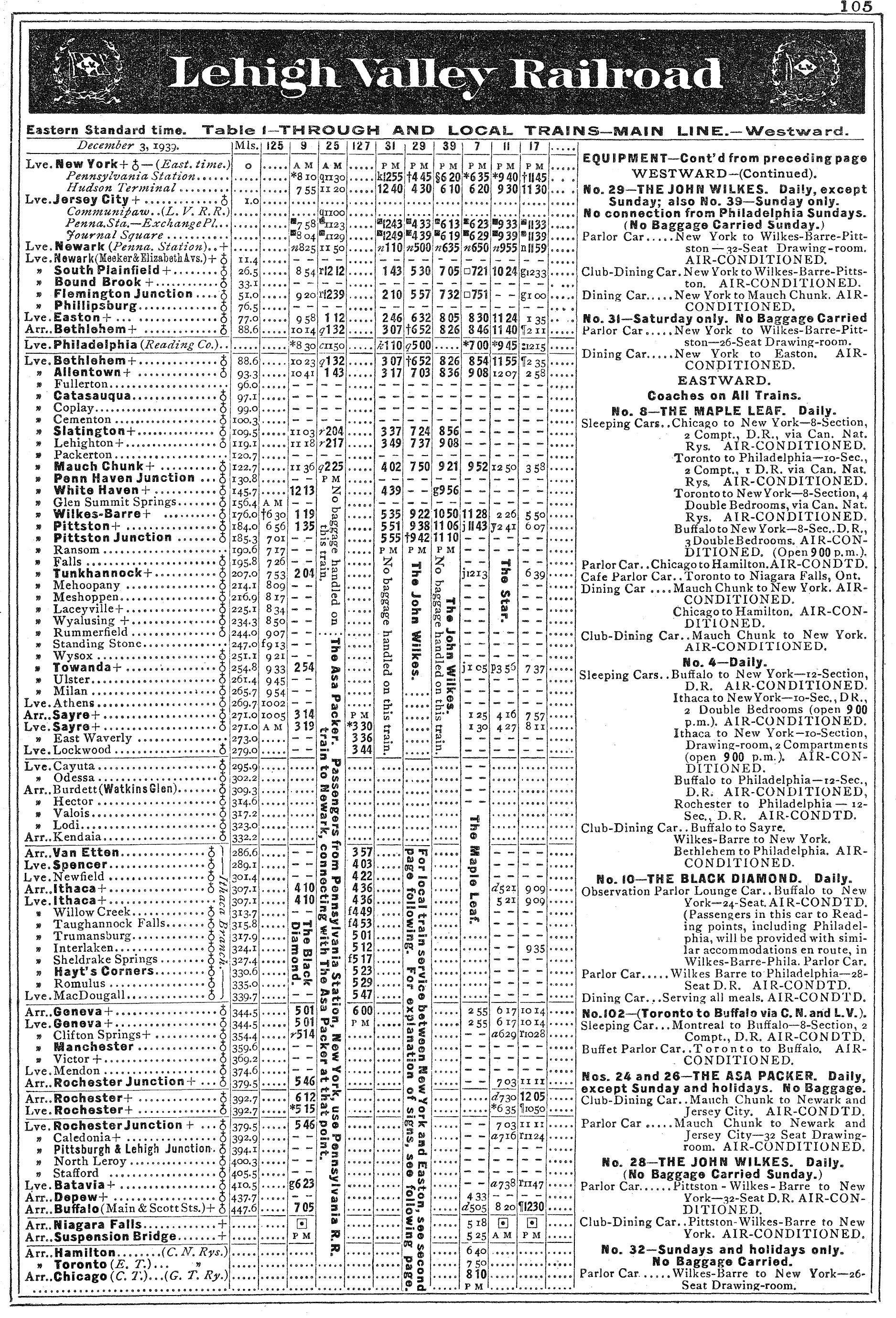

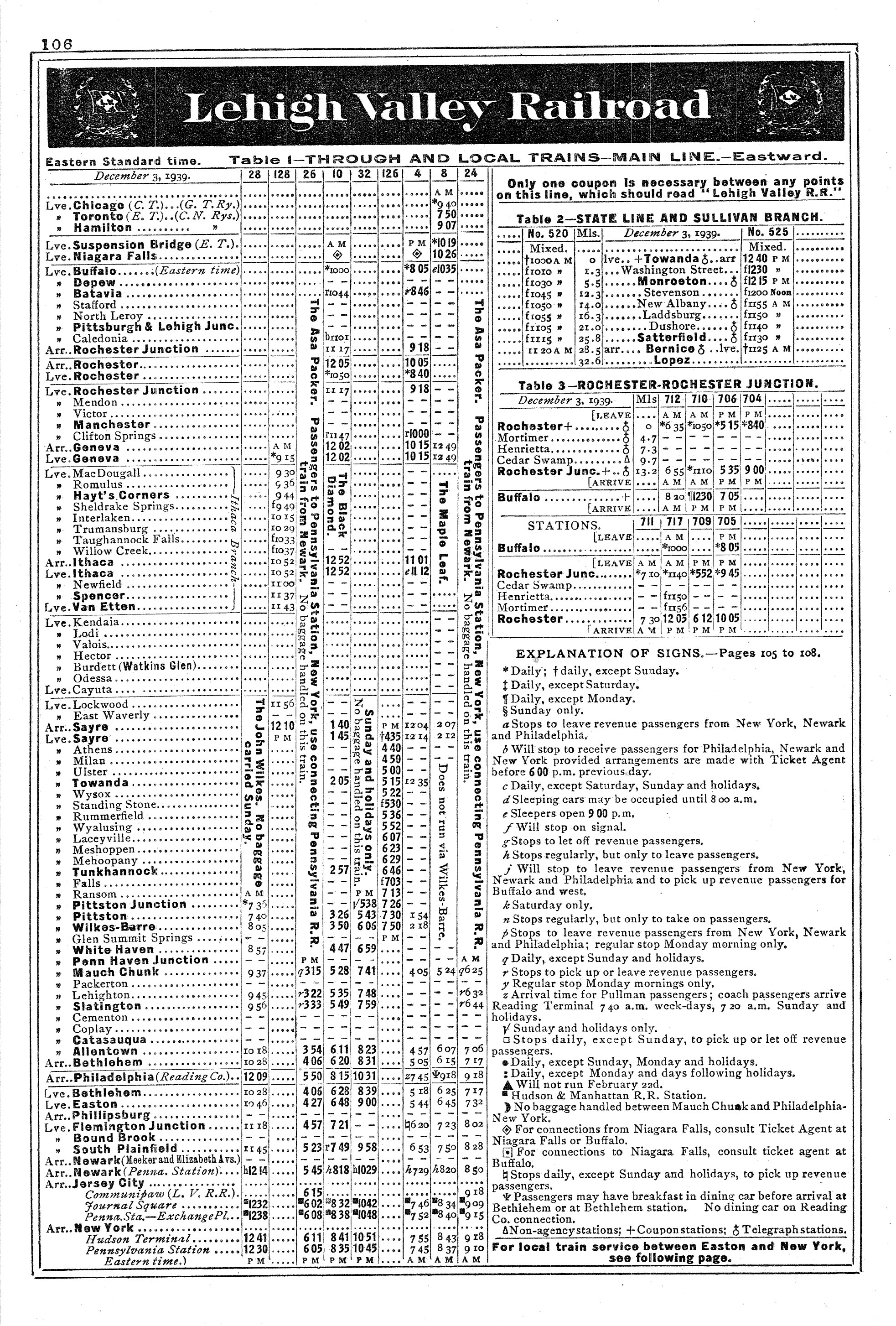

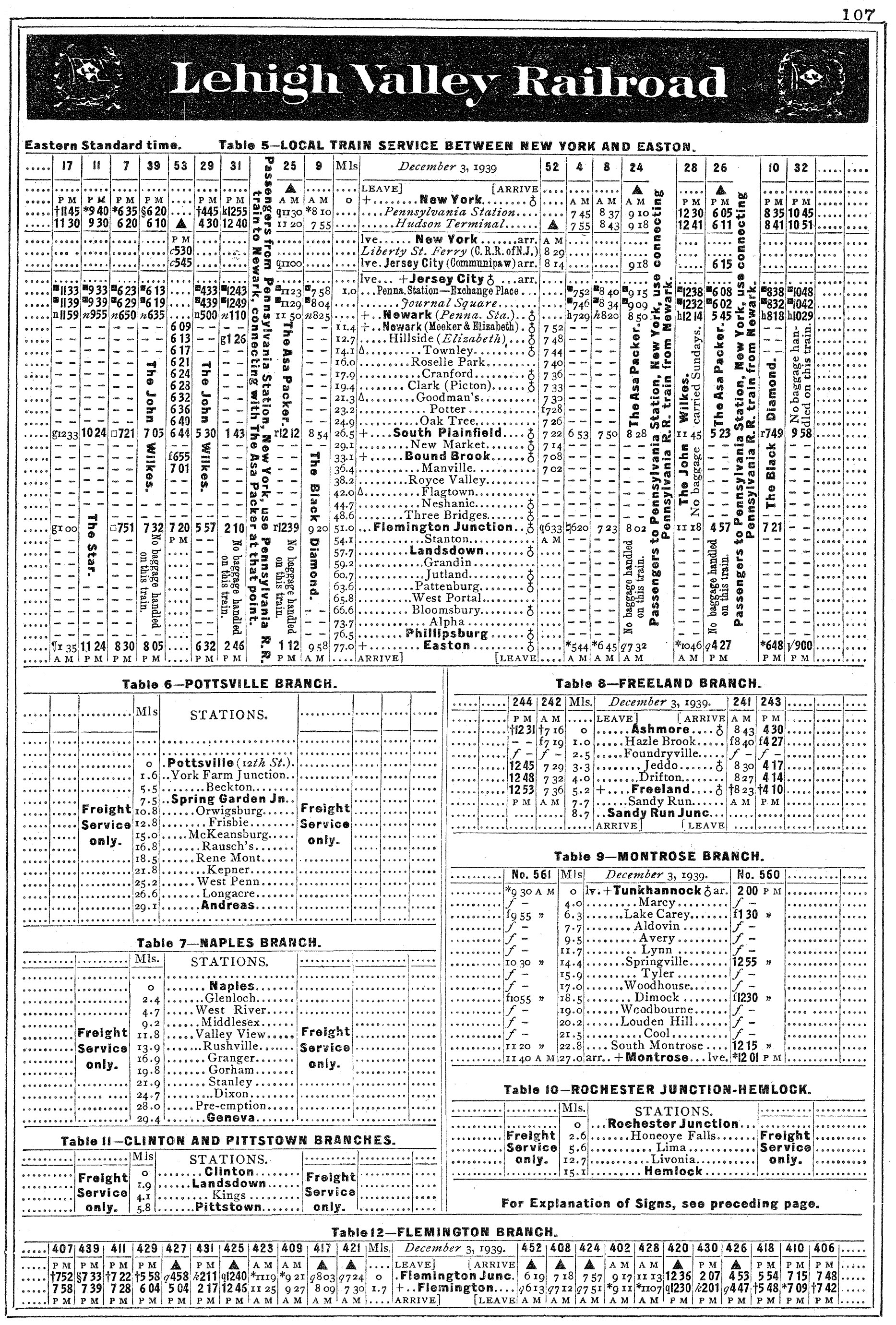

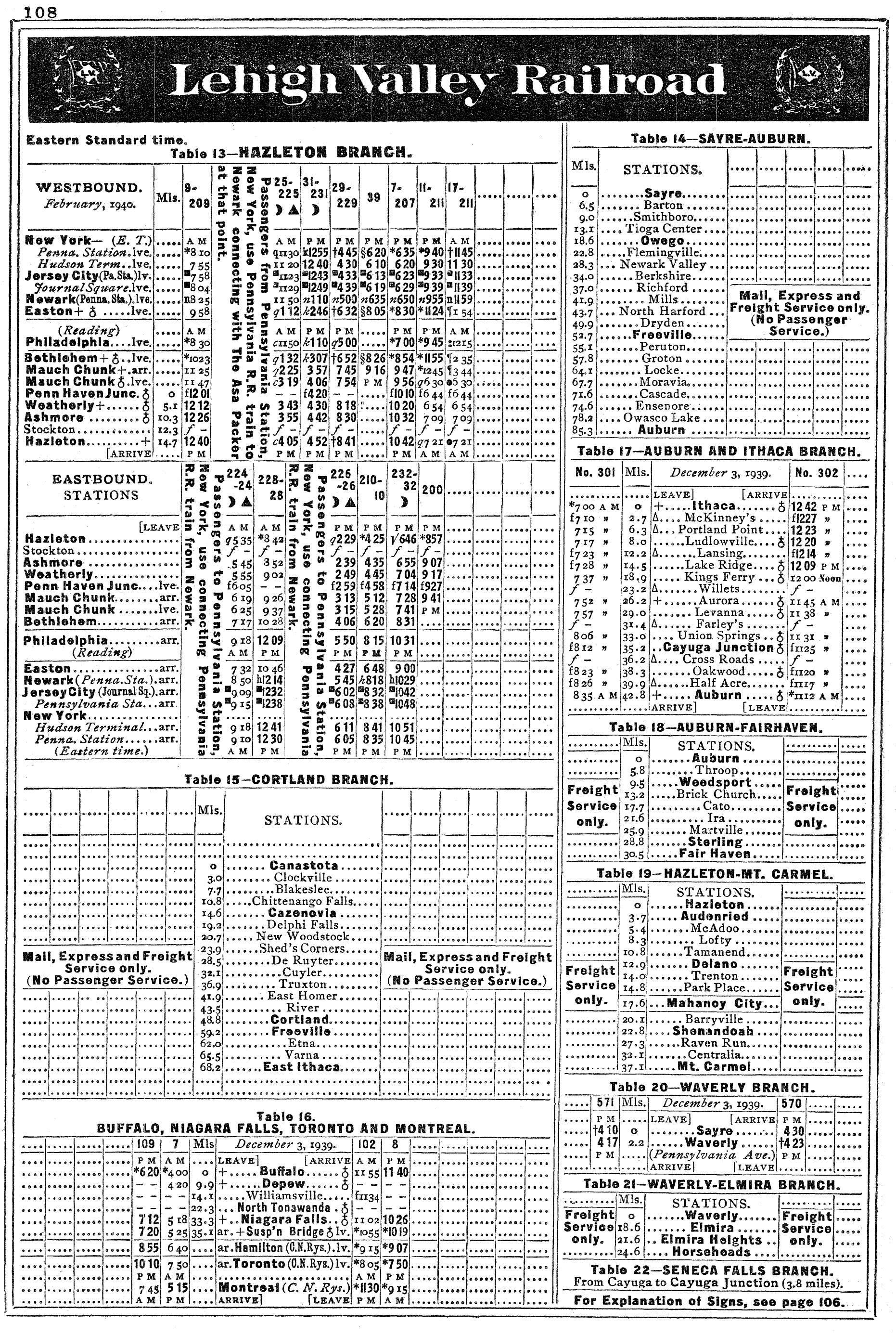

Timetables (1940)

During 1871 the LV acquired the Morris Canal, which provided it waterfront property in Jersey City although the railroad still required building its own rails to the area. To do this it began a branch from its main line at South Plainfield, which extended northeasterly to Jersey City.

There very various subsidiaries comprising this project, which later collectively became known as the Lehigh Valley Terminal Railway. In 1891 it opened service to Newark, just across the Hackensack River from Jersey City, where it constructed the large Oak Island Yard.

Lehigh Valley RS3 #215 and RS2 #213 lead an eastbound freight over the Erie Lackawanna as the train crosses the Chenango River at Binghamton, New York in February, 1971. Photographer not listed. Author's collection.

Lehigh Valley RS3 #215 and RS2 #213 lead an eastbound freight over the Erie Lackawanna as the train crosses the Chenango River at Binghamton, New York in February, 1971. Photographer not listed. Author's collection.Finally, in 1899 it opened direct rail service to the Hudson River and later built a major waterfront terminal which sat on the northern side of CNJ's Jersey City Terminal.

By the turn of the 20th century the LV’s system was largely complete boasting a network of more than 1,350 route miles while its main line stretched 448 miles from Jersey City to Buffalo. Unfortunately, after 1900 the company also had an on-again-off-again battle to maintain profitability.

Lehigh University

Asa Packer's greats philanthropic endeavor was the establishment of Lehigh University, chartered in 1865 and named for the railroad.

With the success of the Lehigh Valley, Packer became a multi-millionaire and donated 115 acres in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania along with $500,000 to construct an institution of higher learning in the field of engineering.

Today, the university has branched out to include other academic subjects, offering undergraduate majors in the areas of arts/science and business, as well as various graduate programs. Its enrollment normally hovers between 6,000 to 8,000 students annually, with a staff of more than 1,000 .

It is widely recognized as one of the top colleges in the country and perennially ranks as one of U.S. News & World Report's "Best Colleges," usually among the top 50 nationally.

Lehigh Valley FA/B-1's lead a long mixed freight through Penn Haven Junction (Pennsylvania) within the Lehigh River Gorge, circa 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

Lehigh Valley FA/B-1's lead a long mixed freight through Penn Haven Junction (Pennsylvania) within the Lehigh River Gorge, circa 1960. American-Rails.com collection.20th Century Operations

The Lehigh Valley's control by the Packer family was short-lived after Asa's death. The much more prosperous Philadelphia & Reading (Reading), the richest anthracite carrier alongside the Lackawanna, leased the Lehigh Valley during the early 1890s in an attempt to dominate the anthracite market.

The financial Panic of 1893 ended these dreams after the company fell into bankruptcy, resulting in the LV regaining its independence. It was then acquired by banking mogul J.P. Morgan in 1897 who went on to purchase the holdings from the Packer estate, ending their involvement in the company.

Lehigh Valley F7's, led #570, are seen here at work in South Plainfield, New Jersey, circa 1960. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Lehigh Valley F7's, led #570, are seen here at work in South Plainfield, New Jersey, circa 1960. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.Morgan's firm remained in control long after his death, during which time the LV was a well-managed, profitable operation. One can reasonably argue that its long decline began with the stock market's collapse in October of 1929.

The depression not only weakened the railroad financially but decreasing anthracite demand further hurt its bottom line. In 1928 the PRR began acquiring LV stock and continued to do so throughout the years in an increasingly futile attempt to maintain its investment within the declining company. By April of 1962 it, incredibly, controlled 90% of the road.

Decline

While the surge in wartime traffic during the 1940s helped right the ship this was not enough to stabilize the LV's growing financial problems.

Realizing it needed to cut expenses and increase efficiency when, where, and however possible the railroad quickly dieselized its motive power fleet with models ranging from almost every manufacturer. It completed the transition in 1951.

Interestingly, even as earnings continued to sink (the LV would, sadly, show a profit for the last time in 1956 and paid its final dividend in 1957), the railroad tried its best to remain competitive in various ways:

- It handled bridge traffic in conjunction with the Delaware & Hudson.

- Introduced pool service with the Nickel Plate Road in 1964.

- Allied with the CNJ in some territories to reduce costs.

- Introduced high speed intermodal/TOFC (trailer-on-flatcar) trains with names like Apollo and Mercury.

Lehigh Valley F7A #574 lays over at the engine terminal in Oak Island, New Jersey, circa 1960. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Lehigh Valley F7A #574 lays over at the engine terminal in Oak Island, New Jersey, circa 1960. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.While these innovations and ideas were somewhat successful they could not stem the enormous losses mounting by the late 1960s; there was simply too many railroads and not enough traffic.

As much as the railroad tried it was unable to reverse its declining fortunes. Its last hope for survival occurred when the PRR and New York Central created the ill-fated Penn Central Transportation Company in 1968.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boxcab | 100 | 1925 | 1 |

| S1 | 117 | 1950 | 1 |

| S2 | 150-165 | 1942-1949 | 16 |

| S4 | 166-167 | 1951 | 2 |

| RS2 | 210-214 | 1949-1950 | 5 |

| RS3 | 215-216 | 1950 | 2 |

| RS11 | 400-403 | 1960 | 4 |

| C420 | 404-415 | 1964 | 12 |

| FA-1 | 530-548 (Evens) | 1948 | 10 |

| FB-1 | 531-549 (Odds) | 1948 | 10 |

| FA-2 | 580-594 (Evens) | 1950-1951 | 8 |

| FB-2 | 581-587 (Odds) | 1950-1951 | 4 |

| PA-1 | 601-614 | 1948 | 14 |

| C628 | 625-632 | 1965-1967 | 8 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | 135-139 | 1944 | 5 |

| DS-4-4-1000 | 140-148 | 1949-1950 | 9 |

| DRS-4-4-1500 | 200 | 1948 | 1 |

| S12 | 230-243 | 1950 | 14 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW | 106-111 | 1937-1938 | 6 |

| SW900 | 107, 110, 121, 123, 125, 130 | 1957-1960 | 6 |

| SW1 | 112-115, 118-119 | 1939-1950 | 6 |

| NW1 | 120-130 | 1937-1938 | 11 |

| NW2 | 180-186, 220-224 | 1949-1950 | 12 |

| SW8 | 250-276 | 1950-1952 | 27 |

| SW9 | 280-292 | 1951 | 13 |

| GP9 | 300-301 | 1959 | 2 |

| GP18 | 302-305 | 1960 | 2 |

| GP38AC | 310-313 | 1971 | 4 |

| GP38-2 | 314-325 | 1972 | 10 |

| FTA | 500-503 | 1945 | 4 |

| FTB | 500B-503B | 1945 | 4 |

| F3A | 510-528 (Evens) | 1948 | 10 |

| F3B | 511-529 (Odds) | 1948 | 10 |

| F7A | 560-574 (Evens) | 1950-1951 | 8 |

| F7B | 561-571 (Odds) | 1950-1951 | 6 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 60-62 | 1941-1942 | 3 |

| U23B | 501-512 | 1974 | 12 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| F-6 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| G-13 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| J-54, J-55 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| K-5, K-5BS | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| L-3 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| M-37 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| N-5B | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| R-1 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| S-1, S-2 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| T-1 Through T-3 | Wyoming | 4-8-4 |

A trio of new Lehigh Valley GP38-2's lead an eastbound general manifest past Steel Tower in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania during December of 1972. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A trio of new Lehigh Valley GP38-2's lead an eastbound general manifest past Steel Tower in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania during December of 1972. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Conrail

As part of the merger the LV was offered to either Norfolk & Western or Chesapeake & Ohio, both profitable systems, as a means of maintaining competition in the Northeast (each had connections to the LV at Buffalo). However, each declined due to the LV's light traffic, enormous debt, and declining physical condition.

As Penn Central literally fell apart from its first day of service it came as no surprise that just two years later, in 1970, it declared bankruptcy. This move sent shock waves not only within financial circles but also throughout the railroad industry.

Its fall helped bring down most other systems in Northeast, setting up a catastrophic situation as the region threatened total shutdown.

Faced with the realization of either a nationalized takeover or a reorganization the government was forced to step in. It created the quasi-public Consolidated Rail Corporation, better known as Conrail, which began operations on April 1, 1976.

As Conrail created what it deemed the most profitable network from these bankrupt carriers very few lines of the former Lehigh Valley system were utilized.

Today, nearly the entire western half of the LV is gone and what remains is operated by the Reading & Northern and Conrail successor, Norfolk Southern.

Recent Articles

-

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:45 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train!