Nickel Plate Road (Railroad): Map, History, Rosters

Last revised: October 16, 2024

By: Adam Burns

In his book, "More Classic American Railroads," author and historian Mike Schafer notes the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad (NYC&StL) gained its famous nickname, Nickel Plate Road, from a Norwalk, Ohio newspaper columnist who complimented its high standard of construction by referring to it as a "double-track nickel-plated railroad."

Its 2,200-mile network linked Buffalo with Chicago and St. Louis within the hotly contested Midwestern market while the late-era addition of the Wheeling & Lake Erie provided significant coal and steel traffic.

History

The Nickel Plate was not your average "David among Goliath's," struggling to hold its own against larger competitors. It was built to impeccably high standards with a physical plant capable of high-speed service that shined in the post-World War II era.

As a result, all three trunk lines (Pennsylvania, New York Central, and Baltimore & Ohio) occasionally shifted their own trains (including flagship services) onto the Nickel Plate.

In addition to having few branch lines and only a modest passenger business, the railroad earned strong profits during a time when many others were struggling.

It did so well, in fact, that according to John Rehor's excellent book, "The Nickel Plate Story," the company grossed $2.8 billion between 1945 and the 1964 merger with Norfolk & Western while enjoying profits of $250 million. Today, many of the Nickel Plate's primary corridors remain in use under successor Norfolk Southern.

Nickel Plate Road PA-1's, led by #190, have the "Nickel Plate Limited" (Chicago - Buffalo) at Hammond, Indiana on April 1, 1956. The lead locomotive was scrapped long ago. However, Doyle McCormack nearly completed the restoration of a replica #190, originally built as Santa Fe #62-L, during a 21-year period before selling the locomotive to Genesee Valley Transportation in 2023. Gordon Lloyd photo.

Nickel Plate Road PA-1's, led by #190, have the "Nickel Plate Limited" (Chicago - Buffalo) at Hammond, Indiana on April 1, 1956. The lead locomotive was scrapped long ago. However, Doyle McCormack nearly completed the restoration of a replica #190, originally built as Santa Fe #62-L, during a 21-year period before selling the locomotive to Genesee Valley Transportation in 2023. Gordon Lloyd photo.The Nickel Plate Road was all but universally unique in that its original Buffalo - Chicago main line was conceived, surveyed, and built entirely with private capital.

Its only comparable counterpart was the Virginian Railway, constructed with millionaire Henry Huttleston Rogers' support to serve the southern Appalachian coal fields.

The Nickel Plate's story begins with the Seney Syndicate, led by George Seney, with notable associates including John Martin, Edward Lyman, Alexander White, Watson Brown, Calvin Brice, Charles Foster, Dan Eells, General Samuel Thomas, Columbus Cummings, and William Howard.

At A Glance

2,192 (1950) | |

Chicago - Fort Wayne, Indiana - Fostoria, Ohio - Cleveland - Buffalo Toledo, Ohio - East St. Louis, Illinois Toledo - Wheeling, West Virginia Cleveland - Zanesville, Ohio Sandusky, Ohio - East Peoria, Illinois Indianapolis - Michigan City, Indiana Fort Wayne - New Castle - Rushville/Connersville, Indiana Norwalk - Huron, Ohio Cleveland - Wellington, Ohio | |

Steam: 392 Diesel: 117 | |

Freight Cars: 29,229 Passenger Cars: 117 | |

All had a range of backgrounds, from attorneys to Wall Street speculators, and carried enough financial clout between them to launch a railroad. However, this was not their opening salvo into the high-stakes world where names like Vanderbilt, Gould, and Harriman reigned.

By 1880 the syndicate controlled several systems including the East Tennessee, Virginia & Georgia; Peoria, Decatur & Evansville; and Ohio Central. Combined, they totaled about 2,500 miles.

The group also presided over the 353-mile Lake Erie & Western Railway (LE&W) connecting Fremont, Ohio with Bloomington, Illinois. In time, the LE&W would become part of the modern Nickel Plate system.

Construction

Several anecdotal stories detail why the syndicate wished to expand across the Midwest. One of the most widely published was presented in the book, "The Nickel Plate Road: The History Of A Great Railroad" by Taylor Hampton and the Nickel Plate Road, in which it is said George Seney and William Vanderbilt (heir to the Vanderbilt empire) had a great dislike for one another.

As a means of evening the score, Seney consulted with good friend and associate, Walston Brown, for his opinion on the matter. He suggested constructing a new railroad paralleling Vanderbilt's Lake Shore & Michigan Southern between Buffalo and Chicago.

Whether there is any truth to this account is merely conjecture although as Mr. Rehor's book points out the syndicate did, indeed, need to grow beyond the LE&W if they hoped to remain competitive.

New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway Company

In a move that likely surprised everyone, the group organized the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway Company (NYC&StL) to connect Cleveland and Chicago on February 3, 1881.

Within moments it was immediately capitalized at an astonishing $14,666,666.66. In addition to the main line, a branch would be built to St. Louis while long-term ambitions envisioned a trunk line to either New York City or some point along the Atlantic coast. (Its dreams of reaching the sea ultimately failed while its Gateway City extension did not materialize for another four decades.)

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #762 (S-2) is seen here at what appears to be Chicago, circa 1950. Note the NW2 in the background. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #762 (S-2) is seen here at what appears to be Chicago, circa 1950. Note the NW2 in the background. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.It was an incredibly bold endeavor during an era when the great eastern systems (B&O, PRR, and NYC) had already reached Chicago and were well entrenched throughout the Midwest. As the project got underway it became a mix of new construction and acquisition.

The group sought a route built to high engineering standards that offered strong competition against the mighty LS&MS. It was further bolstered by the surveyors' determination that its Cleveland - Chicago leg (340 miles) would be 15 miles shorter than its counterpart's.

Only months after the Nickel Plate's creation a series of corporate maneuverings brought an eastern extension to Buffalo (this 185-mile corridor would also closely parallel the LS&MS) and saw capitalization raised to $35 million.

With copious amounts of cash on-hand and much of the survey work already complete, the syndicate wasted no time in getting under way.

Historically, many of the names we know so well today, from the B&O to Southern Pacific, required many decades in piecing together their modern networks. By contrast, the Nickel Plate was finished in a single year!

Logo

The summer of 1881 witnessed 10,000 men at work all along the entire 523-mile corridor. While the task appeared quite daunting, the right-of-way was not entirely built from scratch.

There were a series of acquisitions between Frankfort, Indiana and Tiffin, Ohio (via Fort Wayne) that greatly aided construction efforts:

- In September of 1880 the small Frankfort & Kokomo was purchased connecting its namesake towns (25 miles)

- The abandoned Wabash & Erie Canal's tow-path between Largo and the Ohio state line offered a ready-made right-of-way between those points.

- Finally the long-defunct Tiffin & Fort Wayne Rail Road provided more than 100-miles of unused grade nearly ready for rails.

The NYC&StL's actual construction began due west from Arcadia, Ohio along a western connection with the Lake Erie & Western. The line had reached McComb by June 22nd and crews were soon laying up to one mile per day. After less than five months of construction, the first train rolled into Fort Wayne on November 3rd.

As this was ongoing, work was already underway to the west while at the same time crews were pushing east from a point 6 miles west of Hobart, Indiana (located about 40 miles west of downtown Chicago). The two groups met at Sidney, Indiana on April 5, 1882.

Nickel Plate Road H10-44's #127 and #132 in Bellvue, Ohio, circa 1960. G. Duecher photo, Rick Burn collection.

Nickel Plate Road H10-44's #127 and #132 in Bellvue, Ohio, circa 1960. G. Duecher photo, Rick Burn collection.During the fall of 1881 work began on the section east of Fostoria where rails had reached Bellevue (future location of yard and terminal facilities) by year's end. While much of the Nickel Plate west of Cleveland was now finished crews had also graded more than 100 miles east of the city.

At the end of 1881 some 270 miles, or more than half of the main line, was complete. To the east, crews finished track-laying as far as Brocton, New York in March with the remaining 50 miles to Buffalo built in conjunction with the Buffalo, Pittsburgh & Western, a Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary.

The NYC&StL laid a second track along this stretch and the two companies shared the property throughout Nickel Plate's history; the PRR utilized the eastbound track while the NYC&StL occupied the westbound main.

By the spring of 1882 it was nearing Chicago's downtown area as Hammond and Grand Crossing was reached in August. At the latter point connections were established with the Illinois Central, LS&MS, and Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago (PRR).

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #831 leads an eastbound freight over the former Wheeling & Lake Erie naer Scio, Ohio on September 5, 1955. Today, this line is abandoned. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #831 leads an eastbound freight over the former Wheeling & Lake Erie naer Scio, Ohio on September 5, 1955. Today, this line is abandoned. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.After performing finishing touches, such as ballasting and erecting telegraph lines, the New York, Chicago & St. Louis officially opened for business on October 23, 1882. It had taken just over 16 months to establish an entirely new Midwestern railroad.

The industry's big players were undoubtedly shocked by what had transpired although, oddly, none bothered to stop or stall the project. Even the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad appeared indifferent. When it all began, Vanderbilt initially took a wait-and-see approach. Once he realized it would, indeed, be built he unleashed a blitzkrieg of criticism but ultimately did nothing.

In the end, Vanderbilt eliminated the competition by simply buying it out. At first, Seney and his group publicly stated they had no interest in selling but soon capitulated amid their strained financial situations. On October 26, 1882 the Nickel Plate was sold to the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern for $7.205 million, just three days after it had opened!

System Map (1940)

The Vanderbilt years, perhaps not surprisingly, carried mixed results. The NYC&StL offered great potential but as a New York Central competitor it could not be allowed too much success. At the same time, it had cost so much money that leaving it to wither was not an option.

New York Central And Van Sweringens

During the early 20th century some modernization was undertaken to improve bridges, install automatic block signals, upgrade rail (80 pounds-per-yard), and construct new terminal facilities (roundhouses and auxiliary buildings). While these betterments helped more was needed to meet growing demand.

Over time, the Nickel Plate became a persistent thorn in New York Central's side; it was a superfluous corridor in a region NYC already thoroughly served.

At the same it carried incredible potential and could make life miserable as an independent. The compromise, as it turns out, was handing it off to a third party with no previous experience in the industry.

The Van Sweringen brothers, Oris Paxton and Mantis James, of Cleveland had gotten their start in real estate during 1905. They became fairly successful in this business and then turned their attention to a rapid-transit line to service their new suburb of Shaker Heights, then under development.

After scouting potential opportunities they realized the Nickel Plate's east-to-west route through the city offered just what they needed. Using every bit of collateral available they managed to scrape together $2 million as a down payment and gained control of the railroad on July 5, 1916.

The Vans blossomed into adept, highly esteemed railroaders who were nearly able to string together a fifth eastern trunk line through control, and eventual merger, of the Nickel Plate, Chesapeake & Ohio, Erie Railroad, and Pere Marquette.

What was dubbed the "Greater Nickel Plate System" would have been a powerful carrier owning 9,213 route miles in the United States and another 337 miles through southern Ontario (Pere Marquette).

It would have included Nickel Plate's high-speed main line, Erie's double-tracked Chicago - Jersey City route, and C&O's prodigious southern Appalachian - tidewater corridor.

The new company was projected to boast annual operating revenues of $340 million, ranking it behind only the PRR and NYC. Alas, what some may have deemed an inconsequential issue brought down the Van Sweringen's empire. One of their numerous corporations formed over the years was a secret stock trust, the Vaness Company.

This entity, in theory, could allow the brothers retention of the "Greater Nickel Plate System" even by selling their railroading interests. Up until that point the Vans had held a sterling reputation in financial circles (despite their heavy debt) as well as at the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #966 (H-5b) is seen here in Bellevue, Ohio, circa 1956. The Mikado was built as #525 by Alco's Brooks Works in August, 1917. She was renumbered in December, 1955 and then retired in April, 1958. The engine was subsequently sold to Canton Iron & Steel in April, 1963. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #966 (H-5b) is seen here in Bellevue, Ohio, circa 1956. The Mikado was built as #525 by Alco's Brooks Works in August, 1917. She was renumbered in December, 1955 and then retired in April, 1958. The engine was subsequently sold to Canton Iron & Steel in April, 1963. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Following this revelation (uncovered by a minority of disgruntled C&O stockholders) the siblings lost their aura of invincibility and the "Greater Nickel Plate" scheme collapsed. Despite this setback, they did pick up two properties which became an integral part of the Nickel Plate; the Lake Erie & Western and Toledo, St. Louis & Western.

As previously discussed, the LE&W was once part of the Seney syndicate. Following the Nickel Plate's sale to New York Central and its subsequent acquisition by the Van Sweringen's, the LE&W had remained under NYC control.

However, the brothers were soon eyeing the property, as it now extended 718 miles from Sandusky, Ohio to Peoria Illinois. In addition to its east-west route the LE&W also operated a pair of north-to-south branches linking Michigan City with Indianapolis and Fort Wayne with Rushville/Connersville. The brothers formally took over the road on April 26, 1922.

Just a month prior, in March, they had also secured the Toledo, St. Louis & Western Railroad. Nicknamed the "Clover Leaf Route," this former narrow-gauge system operated 450 miles via a linear corridor linking Toledo with East St. Louis.

System Map (1950)

Expansion

The "Roarin' 20's" were quite prosperous, economically. However, even then the industry recognized the need for a pared down eastern network. In conjunction with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), consolidation plans were drawn up with the eastern trunk lines to create three or four primary systems (excluding New England).

There was a great deal of jockeying among the prominent names (B&O, NYC, and PRR) although the Van Sweringen's came closest to actually implementing such a proposal. In an interesting move, they tried to once again revive the "Greater Nickel Plate System" just prior to the Great Depression.

This time it was approved by the ICC and would have included the Nickel Plate, C&O (east of Cincinnati), Lackawanna, Pere Marquette, and a handful of smaller short lines. Unfortunately, it too was nixed when the stock market crashed in October of 1929 (in 1932 one final "Four Systems Plan" was put forth but the weak economy killed this last ditch effort).

This event also proved the brothers' swan song. As the economy worsened and banks failed, the siblings were forced to divest control of the Nickel Plate in 1935, losing much of their empire in the process.

One of the Nickel Plate Road's handsome Berkshires (2-8-4), #743, is seen here in service near Cleveland, Ohio, circa 1955. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

One of the Nickel Plate Road's handsome Berkshires (2-8-4), #743, is seen here in service near Cleveland, Ohio, circa 1955. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Modern Era

Incredibly, the railroad managed not only to escape bankruptcy during these lean times but also recovered so strongly that it fully repaid its outstanding debts! It was one of the few railroads to do so.

Initially, things looked very bleak; it lost more than $4.4 million in 1932 then subsequently borrowed $18.1 million from the government's Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to stave off receivership.

The spring of 1933 was a turning point as traffic rebounded and the operating ratio declined (from 75% to 59%). In 1934 the Nickel Plate showed a small profit, its first in three years.

Recovery continued throughout the decade, blemished only by a 1938 deficit. Aside from a strengthening economy, traffic growth was also due to internal improvements aimed at the infrastructure and train speeds.

To accomplish this it purchased new motive power (notably the powerful 2-8-4's), laid heavier rail (over 100 pounds per yard), and introduced centralized traffic control (CTC) in January of 1942.

- This initial segment was located along a 16.7 mile stretch between North East, Pennsylvania and Westfield, New York. By 1954 the Nickel Plate boasted 692 miles of CTC controlled territory and other 255 miles under automatic block signal protection. -

During the 1940's, the Nickel Plate fully regained independence. After the Van Sweringen fallout it had remained under common management with the C&O/Pere Marquette. That changed on December 15, 1942 when it elected a new president, John Davin.

He was a native West Virginian (Montgomery) who had spent a long career on the C&O and continued the tradition of strong, efficient management with which the Nickel Plate had seemingly always been blessed.

Nickel Plate Road PA-1 #185 wearing the classic "Bluebird" livery. The railroad owned only eleven examples of these handsome engines, which led the railroad’s late era passenger trains, such as the “Nickel Plate Limited” and “City of Chicago”/'“City of Cleveland.”

Nickel Plate Road PA-1 #185 wearing the classic "Bluebird" livery. The railroad owned only eleven examples of these handsome engines, which led the railroad’s late era passenger trains, such as the “Nickel Plate Limited” and “City of Chicago”/'“City of Cleveland.”Wheeling & Lake Erie Acquisition

Under his watch the railroad began the path towards dieselization and grew once again by leasing the 530-mile Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway on October 11, 1948.

This historic road was a lucrative regional handling everything from coal and coke to steel and general merchandise along a main line connecting Wheeling, West Virginia with Toledo (another route linked Cleveland with Zanesville while branches reached Huron and Lorain).

It lay in the heart of industrialized Ohio, served the Mountain State's northern steel mills, and offered a strategic connection to Detroit's auto manufacturers. It fit quite well within the Nickel Plate's operations, boosting its total system mileage to 2,266.

Upon his death on January 7, 1949 Mr. Davin had overseen the Nickel Plate's greatest year when the company garnered operating revenues of $109.4 million in 1948.

Interestingly, the road to dieselization proved slower than one might expect. Electro-Motive tried in vain to sell the company on its new F3 diesels, and again with the upgraded F7. It even went so far as to adorn the latter demonstrators in a handsome blue and silver livery which closely resembled the road's passenger scheme.

Despite the advantages these covered wagons possessed (offering an additional 1,000 horsepower and increasing average train speeds by up to 7 mph over the 2-8-4's), at high speed operations (a trademark Nickel Plate service) their fuel savings was negligible against the trusty Berkshires.

The railroad also disliked the F units' lack of rear visibility. During the late 1940's the only main line diesels Nickel Plate owned were a fleet of eleven beautiful PA-1's draped in a handsome blue and light grey scheme (the "Bluebird" livery) for passenger service.

In the end, diesels won out, as the auxiliary steam market faded and new models offered additional horsepower with improved sight lines. During the 1950's large batches of the RS11, GP7, and GP9 were ordered until steam had been officially retired by August of 1960.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #727 (S-1) hustles past WV Tower in Hammond, Indiana, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #727 (S-1) hustles past WV Tower in Hammond, Indiana, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Trains

The Nickel Plate maintained an unpretentious passenger service and such modesty was a significant reason for its great success.

When first opened the railroad shared the Illinois Central/Michigan Central's Great Central Depot at Chicago (Lake Street) and New York, Lake Erie & Western's (Erie) Exchange Street Depot in Buffalo.

From a very early period it switched its Windy City connection, moving to the joint Lake Shore & Michigan Southern/Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific's Van Buren Street Union Station on May 1, 1883.

This beautiful terminal was later replaced by the drab La Salle Street Station in 1903, which served the Nickel Plate throughout its corporate existence.

There were also changes at Buffalo when it joined Delaware, Lackawanna & Western at Lackawanna Terminal soon after its March, 1917 opening. The railroad's most impressive facility was Cleveland Union Terminal, an ornate 52-story skyscraper complex opened on January 1, 1928 (after six years of work).

It was constructed by the New York Central/Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway ("Big Four") and shared by the NYC&StL.

According to Mr. Rehor's book it featured 17.1 miles of overhead D.C. electrification (3,000-volt) extending from NYC's Collinwood Yard to Linndale Yard. The entire grounds, which cost $179 million, featured two suburban stations, a rapid-transit line, and commercial buildings.

Nickel Plate Limited: (Chicago - Buffalo)

Blue Arrow: (Cleveland - St. Louis)

Blue Dart: (St. Louis - Cleveland)

City of Chicago: (Buffalo - Chicago)

City of Cleveland: (Chicago - Buffalo)

Commercial Traveler: (Toledo - St. Louis)

New Yorker: (Chicago - Buffalo)

Westerner: (Buffalo - Chicago)

Norfolk & Western GP30, #2901 (ex-Nickel Plate #901), and new SD45 #1707 are seen here at the former Wabash engine terminal in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1967. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Norfolk & Western GP30, #2901 (ex-Nickel Plate #901), and new SD45 #1707 are seen here at the former Wabash engine terminal in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1967. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Diesel Roster

Alco

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alco | S-2 | 1-6 | DE-3 | AS-10a | 69924-69929 | 1942 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 25-26 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 73931-73932 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 27-28 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 74972, 74982 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 29-30 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 75237-75238 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 31-33 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 75243-75245 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 34-35 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 75250-75251 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 36-42 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 75364-75370 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 43 | DS-4 | AS-10b | 75388 | 1947 | - |

| Alco | S-2 | 44-45 | DS-12 | ASM-10a | 78015-78016 | 1950 | MU Capable |

| Alco | S-4 | 46-53 | DS-16 | AS-10c | 78697-78704 | 1951 | - |

| Alco | S-4 | 54-60 | DS-16 | ASM-10b | 78705-78711 | 1951 | MU Capable |

| Alco | S-4 | 61 | - | ASM-10c | 79520 | 1952 | MU Capable |

| Alco | S-4 | 65-73 | - | AS-10d | 79521-79529 | 1952 | - |

| Alco | S-4 | 74-77 | - | AS-10e | 80468-80471 | 1952 | - |

| Alco | S-4 | 78-83 | - | ASM-10d | 80447-80452 | 1953 | MU Capable |

| Alco | S-1 | 85 | DS-13 | AS-6a | 78139 | 1950 | MU Capable |

| Alco | PA-1 | 180-186 | DP-1 | AP-20a | 75330-75336 | 1947 | MU Capable as well as equipped with steam generator and train stop. |

| Alco | PA-1 | 187-190 | DP-1 | AP-20a | 75454-75457 | 1948 | MU Capable as well as equipped with steam generator and train stop. |

| Alco | RSD-12 | 325-332 | - | ARX-18a | 81955-81962 | 1957 | - |

| Alco | RSD-12 | 333 | - | ARX-18a | 82378 | 1957 | - |

| Alco | RS3 | 535-557 | - | ARS-16a | 80707-80729 | 1954 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 558-562 | - | ARS-18a | 81459-81463 | 1956 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 563-567 | - | ARS-18b | 82832-82836 | 1958 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 568-572 | - | ARS-18b | 82863-82867 | 1958 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 573-575 | - | ARS-18d | 83541-83543 | 1960 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 576-577 | - | ARS-18d | 83580-83581 | 1960 | - |

| Alco | C420 | 578 | - | ARS-20a | 84792 | 1964 | - |

| Alco | RS11 | 850-863 | - | ARS-18c | 83014-83027 | 1959 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS11 | 864 | - | ARS-18c | 83394 | 1959 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS36 | 865-868 | - | ARS-18e | 83697-83700 | 1962 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS36 | 869-870 | - | ARS-18e | 84100-84101 | 1962 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS36 | 871-872 | - | ARS-18e | 84105-84106 | 1962 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS36 | 873 | - | ARS-18e | 84104 | 1962 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| Alco | RS36 | 874-875 | - | ARS-18f | 84102-84103 | 1962 | Equipped with steam generator and train stop. |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin | VO-1000 | 100-101 | DS-6 | BS-10a | 72849-72850 | 1947 | - |

| Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton | AS-16 | 320-321 | - | BRS-16a/BARS-18a | 75943-75944 | 1953 | - |

| Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton | AS-16 | 322-323 | - | BRS-16b/BERS-17a | 76028- | 1953 | - |

EMD

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMC | NW2 | 7-8 | DE-2 | ES-10b | 1750, 1698 | 1942 | - |

| EMC | NW2 | 9-10 | DE-2 | ES-10b | 1759, 1756 | 1942 | - |

| EMD | NW2 | 11-14 | DS-5 | ES-10c | 4985-4988 | 1948 | - |

| EMD | NW2 | 15-16 | DS-5 | ES-10c | 4989-4990 | 1948 | Dual control stands. |

| EMD | NW2 | 17-22 | DS-5 | ES-10c | 6088-6093 | 1948 | - |

| EMC | NW2 | 95-96 | DS-10 | ES-10a | 998, 1089 | 1940 | - |

| EMC | NW2 | 97-98 | DS-10 | ES-10a | 1422-1423 | 1941 | - |

| EMD | SW1 | 105-106 | DS-15 | ES-6a | 13705-13706 | 1950 | - |

| EMD | SW1 | 107-114 | - | ES-8a | 16352-16359 | 1952 | - |

| EMD | SW7 | 230-232 | DS-14 | ES-12a | 12307-12309 | 1950 | - |

| EMD | SW9 | 233-237 | - | ES-12b | 13955-13959 | 1951 | - |

| EMD | SW9 | 238-244 | - | ES-12c | 16360-16366 | 1952 | - |

| EMD | SD9 | 340-359 | - | ERX-17a | 23155-23174 | 1957 | - |

| EMD | GP7 | 400-412 | - | ERS-15a | 13692-13704 | 1951 | - |

| EMD | GP7 | 413-422 | - | ERS-15b | 17088-17097 | 1953 | - |

| EMD | GP7 | 423-447 | - | ERS-15c | 18591-18615 | 1953 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 448 (1st) | - | ERS-17a | 20453 | 1955 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 448 (2nd) | - | ERS-17a | 23756 | 1957 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 449-476 | - | ERS-17a | 20454-20481 | 1955 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 477-479 | - | ERS-17b | 20482-20484 | 1955 | Equipped with steam generator and train stop. |

| EMD | GP9 | 480-482 | - | ERS-17c | 21908-20910 | 1956 | Equipped with steam generator and train stop. |

| EMD | GP9 | 482 (2nd) | - | ERS-17c | 23760 | 1957 | Equipped with steam generator and dual control stands. |

| EMD | GP9 | 483 | - | ERS-17c | 21911 | 1956 | Equipped with dual control stands. |

| EMD | GP9 | 484-485 | - | ERS-17c | 21906-21907 | 1956 | Equipped with steam generator and dual control stands. |

| EMD | GP9 | 486-497 | - | ERS-17d | 21912-21923 | 1956 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 496-497 (2nd) | - | ERS-17d | 23757-23758 | 1957 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 498-503 | - | ERS-17d | 21924-21929 | 1956 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 503 (2nd) | - | ERS-17d | 23759 | 1957 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 504-509 | - | ERS-17d | 21930-21935 | 1956 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 510-529 | - | ERS-17e | 24501-24520 | 1958 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 530-534 | - | ERS-17f | 25073-25077 | 1959 | - |

| EMD | GP18 | 700-709 | - | ERS-18a | 26023-26032 | 1960 | - |

| EMD | GP9 | 800-814 | - | ERS-17g | 25078-25092 | 1959 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| EMD | GP9 | 900-909 | - | ERS-22a | 27894-27903 | 1962 | Equipped with automatic train stop. |

| EMD | GP35 | 910 | - | ERS-25a | 29167 | 1964 | - |

Fairbanks-Morse

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | H10-44 | 125-133 | DS-7 | FS-10a | 10L103-10L111 | 1949 | - |

| FM | H12-44 | 134-138 | - | FS-10a | 12L721-12L725 | 1953 | - |

| FM | H12-44 | 139-145 | - | FS-10b | 12L1082-12L1088 | 1957 | - |

| FM | H12-44 | 146-155 | - | FS-12c | 12L1101-12L1110 | 1958 | - |

General Electric

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE | 44-tonner | 90 | DS-9 | GS-4a | 30249 | 10/1949 | - |

Lima-Hamilton

| Builder | Model | Original Number(s) | Original Class | 1951 Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lima-Hamilton | 1,000 HP Switcher | 305-308 | DS-8 | LS-10a | 9324-9327 | 1949 | - |

| Lima-Hamilton | 1,200 HP Switcher | 309-312 | DS-11 | LS-12a | 9413-9416 | 1950 | - |

All-Time Steam Roster

| Road Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-32 | A | 4-4-0 | Brooks | 5/1881-5/1882 |

| 33-39 | F | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 10/1882 |

| 33-39 (2nd) | P-1 | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 5/1909 |

| 40-49 (1st) | A | 4-4-0 | Hinkley | 11/1881-12/1881 |

| 40-49 (2nd) | P | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 12/1905 |

| 45-49 (3rd) | M | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1910 |

| 50-68 | F | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 10/1882-11/1882 |

| 50-54 (2nd) | P | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 10/1906 |

| 55-64 (2nd) | P-1 | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 3/1908 |

| 50-59 (3rd) | B-11a | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1916 |

| 60-64 (3rd) | B-11a | 0-6-0 | Lima | 5/1917 |

| 65-69 (2nd) | B-11b | 0-6-0 | Lima | 5/1917 |

| 69-83 | G | 2-6-0 | Brooks | 1/1888-8/1888 |

| 70-74 (2nd) | B-11c | 0-6-0 | Lima | 3/1918 |

| 75-80 (2nd) | S* | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1913 |

| 75-79 (3rd) | B-11c | 0-6-0 | Lima | 3/1918 |

| 84-88 | H | 2-6-0 | Brooks | 3/1890 |

| 89-98 | I | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 3/1891-5/1891 |

| 99-108 | J | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 9/1892-10/1892 |

| 109-113 | K | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 1/1896 |

| 114-118 | K | 4-6-0 | Schenectady | 1/1896 |

| 119-128 | N | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 2/1902 |

| 129-148 | N-1 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1903-3/1904 |

| 149 | N-2 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1906 |

| 150-167 | B | 4-4-0 | Brooks | 1/1882-4/1882 |

| 150-158 (2nd) | N-2 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1906 |

| 156-158 (3rd) | R | 4-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1913 |

| 159-161 (2nd) | N-3 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 8/1907 |

| 160-161 (3rd) | K-1a | 4-6-2 | Lima | 12/1922 |

| 162-166 | N-4 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 3/1908 |

| 162-163 (2nd) | K-1a | 4-6-2 | Lima | 12/1922 |

| 164-166 (3rd) | K-1a | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1923 |

| 167 | K-1b | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1923 |

| 168-175 | C | 4-4-0 | Brooks | 8/1882-9/1882 |

| 168-169 (2nd) | K-1b | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1923 |

| 170-173 (2nd) | L-1a | 4-6-4 | Alco/Brooks | 3/1927 |

| 174-175 (2nd) | L-1b | 4-6-4 | Lima | 11/1929 |

| 176-181 | O | 4-4-0 | Alco/Brooks | 6/1904 |

| 176-177 (2nd) | L-1b | 4-6-4 | Lima | 11/1929 |

| 199 | - | 0-4-2T | Baldwin | 8/1879 (Ex-CP&A**) |

| 200-209 | D | 0-4-0 | Brooks | 3/1882 |

| 200-204 (2nd) | U-2 | 0-8-0 | Lima | 5/1918 |

| 210-213 | E | 0-6-0 | Brooks | 4/1882 |

| 210-213 (2nd) | U-3b | 0-8-0 | Lima | 5/1924 |

| 214-219 | U-3b | 0-8-0 | Lima | 5/1924 |

| 220-229 | U-3c | 0-8-0 | Lima | 6/1925 |

| 300-304 | C-17 | 0-8-0 | Lima | 7/1934 |

| 335-358 | P-2 | 4-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1910-6/1911 |

| 359-366 | P-3 | 4-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 9/1913 |

| 448-453 | N-5 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 5/1911 |

| 454-459 | N-6 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1913 |

| 460-474*** | T | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 1903 |

| 500-509 | H-5a | 2-8-2 | Lima | 3/1917-5/1917 |

| 647-661 | H-6e | 2-8-2 | Lima | 1/1924 |

| 662-671 | H-6f | 2-8-2 | Lima | 6/1924 |

| 700-714 | S | 2-8-4 | Alco | 9/1934-11/1934 |

| 715-717 | S-1 | 2-8-4 | Lima | 6/1942 |

| 718 (1st) | G-10s | 2-8-0 | Frankfort Shops | 12/1923 |

| 718 (2nd) | S-1 | 2-8-4 | Lima | 6/1942 |

| 719-739 | S-1 | 2-8-4 | Lima | 6/1942-5/1943 |

| 740-779 | S-2 | 2-8-4 | Lima | 1/1944-5/1949 |

| 826-827 | F-7 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin | 10/1907 |

* Reclassified as B-10 in March of 1934.

** Built as Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula Railroad #5, retired around December of 1885.

*** Ex-New York Central #5855-5869, built as Lake Shore & Michigan Southern #855-869.

Lake Erie & Western Steam Roster

| Road Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built | Nickel Plate Road Number(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4150-4151 | C-75 | 4-4-0 | Schenectady | 1893 | 302-303 |

| 4155-4156 | C-75a | 4-4-0 | Schenectady | 1895 | 304-305 |

| 4163-4165, 4168 | C-76 | 4-4-0 | Schenectady | 1892 | 306-309 |

| 4246, 4248 | C-49 | 4-4-0 | Baldwin | 5/1902-7/1902 | 300-301 |

| 4250-4252 | U-3a | 0-8-0 | Lima | 1/1920 | 205-207 |

| 4260-4264 | B-4o | 0-6-0 | Brooks | 4/1889 | 27-31 |

| 4275-4277 | B-11d | 0-6-0 | Alco | 12/1913 | 80-82 |

| 4365-4374 | B-54 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Pittsburgh | 5/1902-6/1902 | 32-41 |

| 4377, 4384, 4390 | B-55 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1902 | 42-44 |

| 4392-4393 | B-55 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1902 | 45-46 |

| 5330, 5332 | E-40 | 2-6-0 | Brooks | 3/1889 | 310-311 |

| 5336-5337 | E-40 | 2-6-0 | Brooks | 7/1889 | 312-313 |

| 5501-5503 | G-41 | 2-8-0 | Brooks | 1/1889 | 400-402 |

| 5505-5506 | G-41 | 2-8-0 | Brooks | 1/1889 | 403-404 |

| 5509-5511 | G-41 | 2-8-0 | Brooks | 2/1889 | 405-407 |

| 5513-5514 | G-41 | 2-8-0 | Brooks | 2/1889 | 408-409 |

| 5515-5518 | G-44 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 6/1904 | 375-378 |

| 5520-5539 | G-44 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 6/1904 | 379-398 |

Please note that the class information listed is how these locomotives were assigned under the Nickel Plate.

Toledo, St. Louis & Western Steam Roster

| Road Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built | Nickel Plate Road Number(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | B-5 | 0-6-0 | Rhode Island | 1/1893 | 704 |

| 5-6 | B-6 | 0-6-0 | Dickson | 7/1902 | 705-706 |

| 7-12 | B-7 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 8/1907 | 707-712 |

| 14-15 | B-8 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 1/1904 | 714-715 |

| 16-17 | B-12 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 1/1921 | 716-717 |

| 31, 33 | - | 4-4-0 | Rhode Island | 6/1887 | 731, 733 |

| 40-43 | P-4 | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 3/1901 | 740-743 |

| 44-45 | E-3 | 4-4-2 | Alco/Brooks | 3/1904 | 744-745 |

| 109-111 | P-5 | 4-6-0 | Richmond | 8/1900 | 809-811 |

| 120-125 | F-6 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin | 5/1901 | 820-825 |

| 130-131 | G-1 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 2/1902 | 830-831 |

| 132-133 | G-2 | 2-8-0 | Alco | 1/1904 | 832-833 |

| 134-135 | G-3 | 2-8-0 | Pittsburgh | 2/1900 | 834-835 |

| 136 | G-4 | 2-8-0 | Rogers | 2/1908 | 836 |

| 150-159 | P-6 | 4-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 11/1904 | 850-859 |

| 160-189 | G-10 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 2/1905-12/1905 | 860-889 |

| 190-194 | G-7 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 11/1913 | 890-894 |

| 201-205 | G-8 | 2-8-0 | Lima | 12/1916 | 901-905 |

| 206-216 | G-9 | 2-8-0 | Lima | 12/1921-5/1922 | 906-916 |

Please note that the class information listed is how these locomotives were assigned under the Nickel Plate.

One of the Nickel Plate Road's fine 2-8-4 Berkshires, #752 (S-2), is seen here in Chicago, circa 1955. The railroad's fleet of 80 examples were all retired between 1957-1964. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

One of the Nickel Plate Road's fine 2-8-4 Berkshires, #752 (S-2), is seen here in Chicago, circa 1955. The railroad's fleet of 80 examples were all retired between 1957-1964. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Norfolk & Western Acquisition

The 1950's were generally good although increased competition and rising costs affected the Nickel Plate like the rest of the industry. It implemented a new service at this time, piggyback, on July 12, 1954 between Cleveland and Chicago. After successful trials, trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) trains were extended to Buffalo and New York in conjunction with other carriers.

A recession in 1957-1958 was a nuisance but spoke to the bigger picture of the Nickel Plate's role within a declining industry. Where did it fit in among a short-list of merged railroads? In the east it all began when the Pennsylvania and New York Central announced their intentions to join in 1957.

Then, the Lackawanna and Erie formed the Erie-Lackawanna on October 17, 1960, creating a 3,000-mile network. As it so happened, the Norfolk & Western was looking to extend its lucrative and vaunted coal traffic across the Midwest and found just such an opportunity through the Nickel Plate Road.

This new marriage (approved by the ICC on April 17, 1963) resulted in a strong Midwest-Tidewater system that included not only the Nickel Plate but also the Wabash, Pittsburgh & West Virginia, and Akron, Canton & Youngstown.

After four years of negotiations, hearings, and planning the new, much larger Norfolk & Western became a reality on October 16, 1964. Today, the Nickel Plate's primary corridors remain important arteries under successor Norfolk Southern, a testament to George Seney's vision all of those years ago.

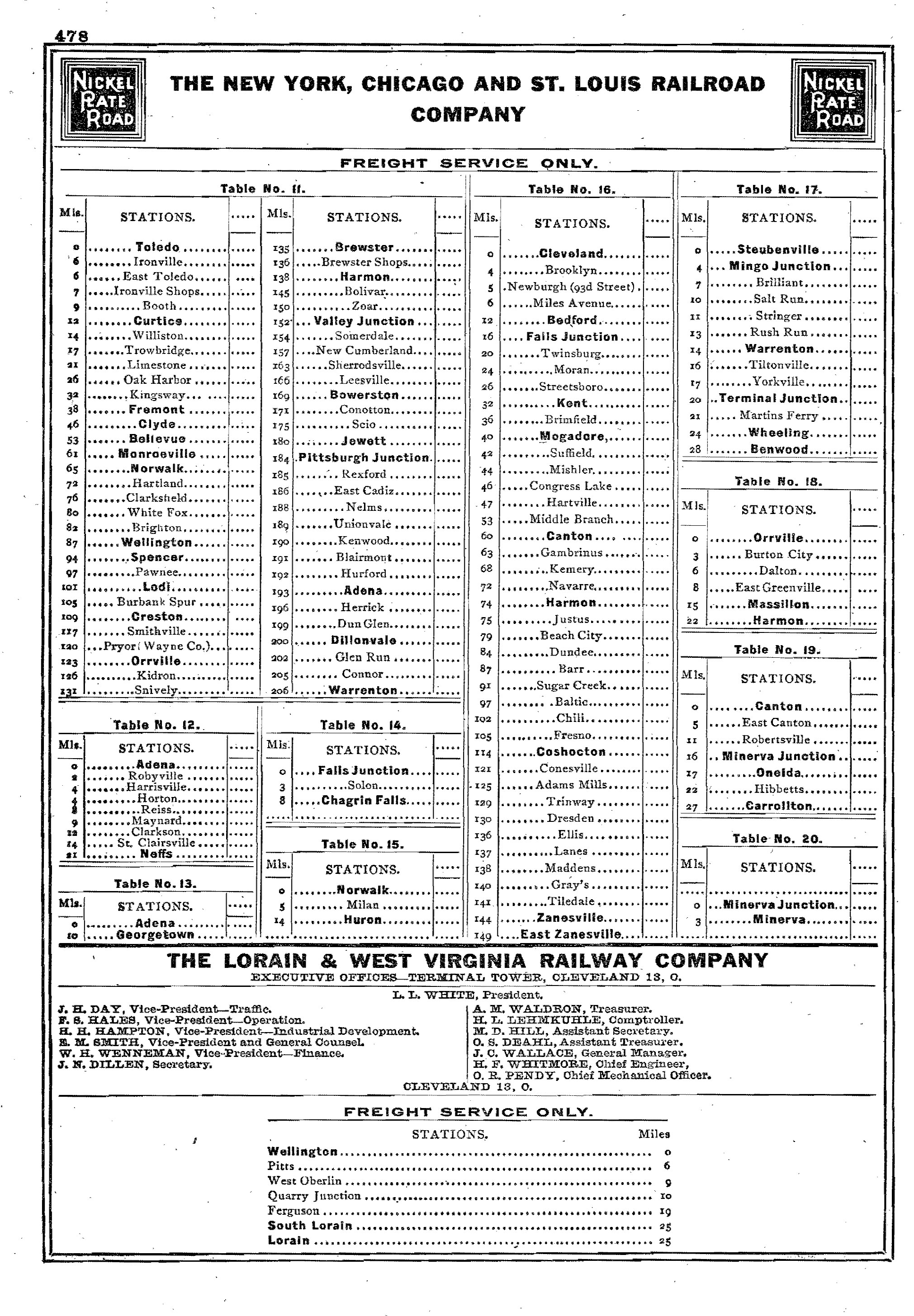

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Photo Gallery

This original slide features Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #742 in freight service late in its career during February, 1958. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

This original slide features Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #742 in freight service late in its career during February, 1958. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #758 is seen here service, circa 1955. Location/Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #758 is seen here service, circa 1955. Location/Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #739 goes for a spin on the turntable at Brewster, Ohio, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #739 goes for a spin on the turntable at Brewster, Ohio, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road PA-1 #187 with a heavyweight passenger train, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road PA-1 #187 with a heavyweight passenger train, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. A trio of Nickel Plate Road GP9s, led by #453 and #474 work freight service near New Haven, Indiana in November, 1958. H.F. Cavanaugh photo. American-Rails.com collection.

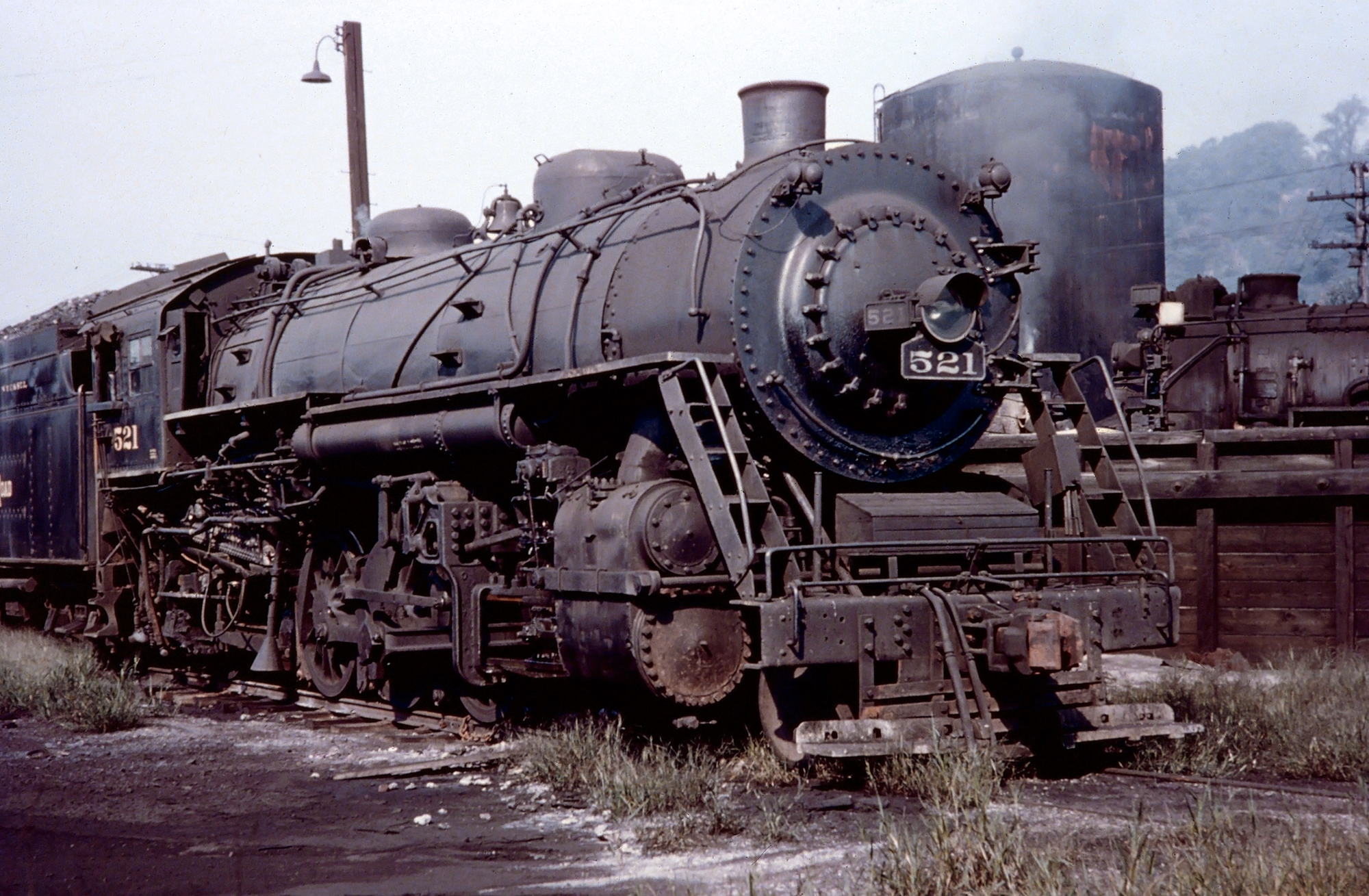

A trio of Nickel Plate Road GP9s, led by #453 and #474 work freight service near New Haven, Indiana in November, 1958. H.F. Cavanaugh photo. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #521 was photographed here by Homer Newlon, Jr. between assignments at Dilonvale, Ohio on September 5, 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #521 was photographed here by Homer Newlon, Jr. between assignments at Dilonvale, Ohio on September 5, 1955. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 0-8-0 switcher #286 was photographed here by Homer Newlon, Jr. between switching assignments at Brewster, Ohio in September, 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 0-8-0 switcher #286 was photographed here by Homer Newlon, Jr. between switching assignments at Brewster, Ohio in September, 1955. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #747 was photographed here in service by Homer Newlon, Jr. at Bellevue, Ohio on July 10, 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

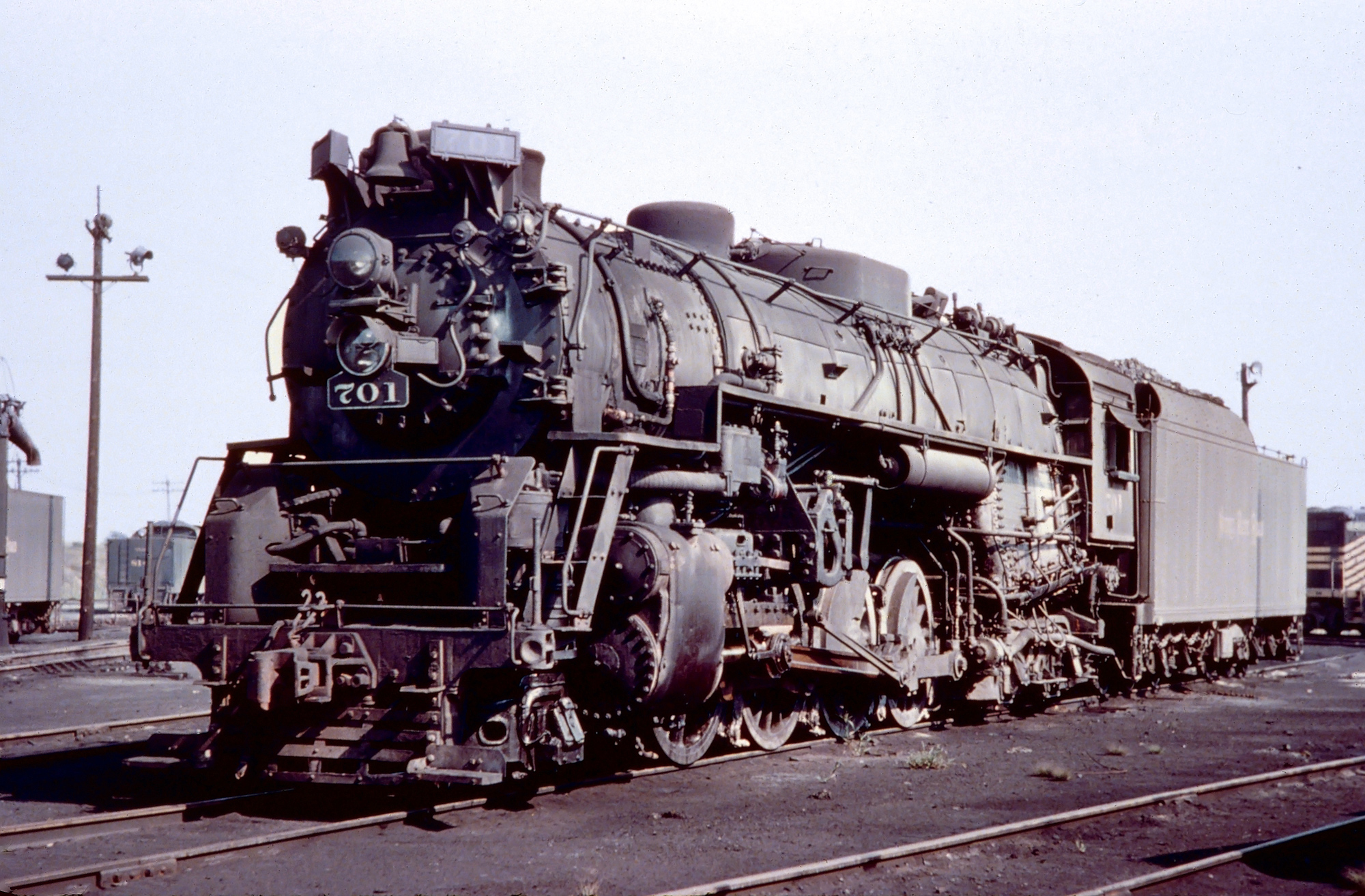

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #747 was photographed here in service by Homer Newlon, Jr. at Bellevue, Ohio on July 10, 1955. American-Rails.com collection. Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #701 was photographed here between assignments by Homer Newlon, Jr. at the Brewster, Ohio terminal on September 20, 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #701 was photographed here between assignments by Homer Newlon, Jr. at the Brewster, Ohio terminal on September 20, 1955. American-Rails.com collection.Sources

- Hampton, Taylor. Nickel Plate Road, The: The History Of A Great Railroad. Newton: Circulation, Publishing And Marketing L.L.C., 1947.

- Rehor, John A. Nickel Plate Story, The. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1965.

- Schafer, Mike. More Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2000.

Recent Articles

-

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase. -

CSX Advances Locomotive Technology to Cut Fuel Use and Emissions

Feb 19, 26 09:43 AM

CSX recently highlighted major progress on its ongoing efforts to reduce fuel consumption, cut greenhouse-gas emissions, and improve operational efficiency across its freight rail network through adva… -

Ohio Railway Museum Unveils “Vision for the Future” Plan

Feb 19, 26 09:39 AM

The Ohio Railway Museum (ORM), one of the nation’s oldest all-volunteer rail preservation organizations, has laid out an ambitious blueprint aimed at transforming its organization. -

B&O Railroad Museum Unveils $38M Expansion

Feb 19, 26 09:24 AM

Western Maryland Railway F7 236 points towards the Mount Clare Roundhouse in Baltimore as part of the B&O Museum. -

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic To Repower Two FPA4s

Feb 19, 26 09:21 AM

A pair of classic, streamlined Alco/MLW FPA4 locomotives that have become signature power on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) are slated for a major mechanical transformation. -

Ohio's Dinner Train Rides At The CVSR

Feb 19, 26 09:18 AM

While the railroad is well known for daytime sightseeing and seasonal events, one of its most memorable offerings is its evening dining program—an experience that blends vintage passenger-car ambience… -

Indiana Dinner Train Rides In Jasper

Feb 19, 26 09:16 AM

In the rolling hills of southern Indiana, the Spirit of Jasper offers one of those rare attractions that feels equal parts throwback and treat-yourself night out: a classic excursion train paired with… -

New Hampshire Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:12 AM

The state's murder mystery trains stand out as a captivating blend of theatrical drama, exquisite dining, and scenic rail travel. -

New York Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 19, 26 09:07 AM

New York State, renowned for its vibrant cities and verdant countryside, offers a plethora of activities for locals and tourists alike, including murder mystery train rides! -

UP, NS Set April 30 Date To Refile Merger Application

Feb 18, 26 04:36 PM

Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern have told federal regulators they will submit a revised merger application on April 30, restarting the formal review process for what would become one of the most co… -

CTDOT May Swap Shore Line East’s Electrics For Diesels

Feb 18, 26 04:20 PM

Connecticut’s Shore Line East (SLE) commuter rail service—one of the state’s most scenic and strategically important passenger corridors—could soon see a major operational change. -

NPS Awards $1.93M To Sioux City Railroad Museum

Feb 18, 26 01:21 PM

The Sioux City Railroad Museum has received a $1.93 million National Park Service grant aimed at pushing the museum’s long recovery from the June 2024 flooding. -

$1.3M Mott Foundation Grant To Help Rebuild Rio Grande 2-8-2 No. 464

Feb 18, 26 09:43 AM

A $1.3 million grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation will fund critical work on steam locomotive No. 464, the railroad’s 1903-built 2-8-2 “Mikado” that has been out of service awaiting heavy… -

NS Unveils Third “Landmark Series” Locomotive

Feb 18, 26 09:38 AM

Norfolk Southern has officially introduced ES44AC No. 8184, the third locomotive in its new “Landmark Series,” a program that spotlights the historic rail cities and communities that helped shape both… -

WMSR's Georges Creek Division: Reviving A Long-Dormant Line

Feb 18, 26 09:34 AM

In 2024 the WMSR announced it was rebuilding part of the old WM. The Georges Creek Division will provide both heritage passenger service and future freight potential in a region once defined by coal… -

Chesapeake & Ohio 614 Restoration Pushes Forward

Feb 18, 26 09:32 AM

One of the most recognizable mainline steam locomotives to survive the post–steam era, C&O 614, is steadily moving through an intensive return-to-service overhaul. -

Montana Dinner Train Rides Near Lewistown

Feb 18, 26 09:30 AM

The Charlie Russell Chew Choo turns an ordinary rail trip into an evening event: scenery, storytelling, live entertainment, and a hearty dinner served as the train rumbles across trestles and into a t…