S.S. Chief Wawatam: History, Photos, Purpose

Published: February 1, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The S.S. Chief Wawatam is a name that resonates with historical significance in the annals of Great Lakes transportation.

The story of the Chief is one of engineering prowess, economic necessity, and cultural preservation, and it reflects the broader narrative of industrial growth in the early 20th century.

The ferry was a coal-powered steel vessel primarily stationed in St. Ignace, Michigan throughout the majority of its operational years. The ship was named in honor of a prominent Ojibwa leader from the 1760s.

At the commencement its service, Chief Wawatam functioned as a multipurpose vessel, serving as both a train and passenger ferry as well as an icebreaker.

It facilitated year-round transit across the Straits of Mackinac, connecting St. Ignace and Mackinaw City, Michigan. The ferry predominantely hauled railcars for the Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic (Soo Line) between the former point and the Pennsylvania and New York Central (later Detroit & Mackinac following Penn Central's sale of the ex-NYC trackage in 1970) from the latter.

Due to the challenging winter conditions, which often prolonged the crossing of the five-mile-wide Straits, the Chief was equipped with comprehensive passenger amenities.

In 1944, its responsibilities as an icebreaker on the upper Great Lakes were superseded by the USCGC Mackinaw, an icebreaking vessel operated by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Following World War II, there was a notable decline in public demand, culminating in the termination of passenger services in 1957 following the completion of the Mackinac Bridge, which provided a direct connection between Michigan's Upper and Lower Peninsulas.

Subsequently, Chief Wawatam transitioned into its final operational role, solely dedicated to the transport of railroad freight cars across the Straits. The railroad docks that facilitated these operations in both Mackinaw City and St. Ignace remain intact to this day.

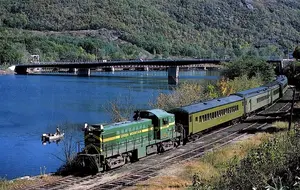

Detroit & Mackinac RS2 #977 unloads the coal-fired "Chief" ("S.S. Chief Wawatam") at Mackinaw City, Michigan in June, 1979. These operations once afforded the D&M with a steady flow of traffic but by the late 1970s they were nearing the end. Rob Kitchen photo.

Detroit & Mackinac RS2 #977 unloads the coal-fired "Chief" ("S.S. Chief Wawatam") at Mackinaw City, Michigan in June, 1979. These operations once afforded the D&M with a steady flow of traffic but by the late 1970s they were nearing the end. Rob Kitchen photo.The Car Ferry

Car ferries, unlike passenger ferries, are designed to transport vehicles and goods. Their evolution was spurred by the industrial boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, demanding efficient transport of raw materials and manufactured goods.

The Great Lakes region, with its contiguous waterway connections to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence Seaway, emerged as a hub of such maritime activities. Among these vessels, the S.S. Chief Wawatam was a quintessential example of the union between necessity and technological innovation.

Genesis

Chief Wawatam was designed by Great Lakes marine architect, Frank E. Kirby. The vessel was launched by the Toledo Shipbuilding Company in Toledo, Ohio, on August 26, 1911, as a successor to the St. Ignace, a wooden ship constructed in 1888.

At the time of its creation, this new steel ship was reputed to be the largest icebreaker in the world. It commenced operations for the Mackinac Transportation Company on October 18, 1911, a venture collaboratively owned by the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway (Soo), the Grand Rapids & Indiana Railroad (PRR), and the Michigan Central Railroad (NYC). These rail networks had routes traversing the Straits of Mackinac.

Engineering and Design

The engineering of the Chief Wawatam was a marvel of its time. Details of its design reveal an acute awareness of the challenges faced by ice-breaking vessels.

The ferry was capable of transporting 18 to 26 railroad cars, contingent on their dimensions, across tracks permanently affixed to the ship's deck. Its steam engines shared a design lineage with those of the Titanic.

Post-1945 refurbishments included the installation of a steering gear sourced from a decommissioned World War II destroyer. While primarily serving to transport freight cars, the Chief also ferried standard passenger rail cars, automobiles, military personnel, and recreational passengers. An oak-furnished lounge catered to those onboard for leisure cruises. In colloquial reference, its name was frequently abbreviated to just "the Chief."

Ensuring year-round ferry service was especially challenging due to the severe ice conditions prevalent in the Straits of Mackinac during winter.

The ferry was engineered with a bow propeller designed not only for propulsion but also to remove water from beneath the ice, facilitating its rupture through gravitational force exerted by the ship's mass. This icebreaking functionality enabled the vessel to open channels for other freighters.

Measuring 338 feet in length with a beam width of 62 feet, the Chief was propelled by three coal-powered triple-expansion steam engines generating 6,000 horsepower.

The vessel is reputedly the last hand-fired, coal-burning ship in commercial service on the Great Lakes. Meanwhile, other coal-fired vessels, like the ferry S.S. Badger (Chesapeake & Ohio), which endured longer in service, employed automated coal stokers.

Operational History

From its maiden voyage in 1911 until its decommissioning in 1984, the Chief served as a vital link in the transportation infrastructure of Michigan. Its decks saw a motley assortment of human and commercial traffic, contributing significantly to the economic development of the region.

The dual nature of its service—ferrying both railcars and passengers—speaks to its adaptability and significance. During its operational years, the ferry forged connections not just between geographical locations but also between communities, sustaining the thriving industries reliant on efficient transport routes.

Cultural and Economic Impact

The Chief Wawatam holds a revered place in regional folklore and cultural memory. It symbolizes the spirit of innovation and resilience that characterized the early 20th-century industrial expansion. Its presence underpinned local economies, especially during the economic depression of the 1930s, providing a steady avenue for commerce.

Culturally, the ferry is an emblem of local heritage, celebrated in numerous narratives, personal anecdotes, and communal lore. It serves as a reminder of a bygone era when maritime activity was the lifeblood of isolated communities.

Preservation Efforts and Legacy

By the late 20th century, with changes in transportation technology and infrastructure, such as the construction of the Mackinac Bridge, the operational need for the Chief Wawatam diminished.

After service officially ended in 1984 it was cut down as a barge in 1989 until the remaining hull was finally scrapped in 2009.

The legacy of the Chief extends beyond its physical remnants. It continues to be a subject of scholarly research, feeding into studies on transportation, regional development, and the sociology of industrial communities. Moreover, it has inspired artistic endeavors, including literature and photography, further embedding it within the cultural fabric of Michigan.

The Chief Wawatam stands as a testament to the engineering capabilities of an era marked by industrial ambition and technological innovation. It embodies the convergence of practical necessity and inventive prowess, charting a narrative that encompasses economic growth, cultural memory, and technological advancement.

Its story is integral not just to regional history but also to the broader chronicles of American industrialization. As such, the Chief remains a symbol not only of local pride but also of a nation's journey through progress and change.

Recent Articles

-

Maryland's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 15, 26 02:59 PM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 15, 26 02:46 PM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 15, 26 02:36 PM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Georgia's Wine Train Rides In Cordele!

Jan 15, 26 02:26 PM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like a t… -

Indiana ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 15, 26 02:22 PM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 15, 26 02:10 PM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides In Ely!

Jan 15, 26 02:01 PM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides In Owosso!

Jan 15, 26 09:46 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Arizona's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 02:04 PM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 01:57 PM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Tennessee ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 01:42 PM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 01:26 PM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

Illinois ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 01:13 PM

Among Illinois's scenic train rides, one of the most unique and captivating experiences is the murder mystery excursion. -

Vermont's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 14, 26 12:57 PM

There are currently murder mystery dinner trains offered in Vermont but until recently the Champlain Valley Dinner Train offered such a trip! -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod!

Jan 14, 26 12:20 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Jan 14, 26 11:31 AM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides In Bardstown!

Jan 13, 26 01:14 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene!

Jan 13, 26 12:44 PM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad (A&SV) delivers. -

Michigan ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 13, 26 11:24 AM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 13, 26 11:11 AM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides At The Grand Canyon!

Jan 13, 26 10:59 AM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Georgia Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 13, 26 10:27 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Indiana Valentine's Train Rides

Jan 12, 26 04:27 PM

If you’ve ever wished you could step into a time when passenger trains were a Saturday-night treat and a whistle echoing across farm fields meant “adventure,” the Nickel Plate Express delivers that fe… -

Ohio Valentine's Train Rides!

Jan 12, 26 04:20 PM

The Hocking Valley Scenic Railway offers one of the region’s most atmospheric ways to experience the Hocking Hills area: from the rhythmic click of jointed rail to the glow of vintage coaches rolling… -

Wisconsin's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 12, 26 03:10 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

California's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 12, 26 02:34 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Wisconsin Scenic Train Rides In North Freedom!

Jan 12, 26 02:20 PM

The Mid-Continent Railway Museum is a living-history museum built around the sights, sounds, and everyday rhythms of small-town and shortline railroading in the early 20th century, what the museum cal… -

Vermont Scenic Train Rides In Burlington!

Jan 12, 26 01:18 PM

Today, GMRC is best known by many travelers for its Burlington-based passenger experiences—most famously the Champlain Valley Dinner Train and the sleek, limited-capacity Cocktails on the Rails. -

Maryland's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 12, 26 01:03 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 12, 26 12:17 PM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Vermont Dinner Train Rides In Burlington!

Jan 12, 26 12:09 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

Connecticut Dinner Train Rides In Essex!

Jan 12, 26 10:39 AM

Connecticut's rail heritage can be traced back to the industry's earliest days and a few organizations preserve this rich history by offering train rides. The Essex Steam Train also hosts dinner-theme… -

Florida Scenic Train Rides In Parrish!

Jan 11, 26 10:26 PM

The Florida Railroad Museum (FRRM) in Parrish offers something increasingly rare in today’s rail landscape: a chance to ride historic equipment over a surviving fragment of an early-20th-century mainl… -

California's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 11, 26 02:28 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Georgia's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 11, 26 02:07 PM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 11, 26 01:43 PM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Minnesota Dinner Train Rides In Duluth!

Jan 11, 26 01:32 PM

One of the best ways to feel the region's history in motion today is aboard the North Shore Scenic Railroad (NSSR), which operates out of Duluth’s historic depot. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello!

Jan 11, 26 12:42 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Alabama's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 10, 26 09:29 AM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Maryland Dinner Train Rides At WMSR!

Jan 10, 26 09:13 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) has become one of the Mid-Atlantic’s signature heritage operations—equal parts mountain railroad, living museum, and “special-occasion” night out. -

Arkansas Dinner Train Rides On The A&M!

Jan 10, 26 09:11 AM

If you want a railroad experience that feels equal parts “working short line” and “time machine,” the Arkansas & Missouri Railroad (A&M) delivers in a way few modern operations can. -

South Dakota's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 10, 26 09:08 AM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular "1880 Train" at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 10, 26 09:07 AM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Missouri's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 10, 26 09:05 AM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 10, 26 09:04 AM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Kentucky Scenic Train Rides At KRM!

Jan 09, 26 11:13 PM

Located in the small town of New Haven the Kentucky Railway Museum offers a combination of historic equipment and popular excursions. -

Washington "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 09, 26 08:53 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 09, 26 08:21 PM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail. -

Kentucky's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 09, 26 01:12 PM

In the realm of unique travel experiences, Kentucky offers an enchanting twist that entices both locals and tourists alike: murder mystery dinner train rides. -

Utah's - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Jan 09, 26 01:05 PM

This article highlights the murder mystery dinner trains currently avaliable in the state of Utah!