Florida East Coast Railway: Map, History, Rosters

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Florida East Coast Railway, like many classic American railroads, carries a rich history filled with both achievement and disappointment. Arguably its greatest legacy was the development of Florida's Atlantic coastline.

Without the FEC cities like Miami, West Palm Beach, and Daytona Beach would simply not exist today.

Through the vision of Henry M. Flagler, who ironically had no interest in the railroad business until launching his vast hotel empire, popular resort destinations like these and others sprang up.

The FEC thrived through the 1920s as the Sunshine State's population exploded. It then quickly declined a decade later and eventually fell into bankruptcy.

The company remained in receivership for more than three decades until a renewed period of growth began in the 1960s with intermodal's revolution. Today, the FEC operates more like a Class I with new motive power and ribbons of welded rail.

In 2012 an exciting announcement stated privately operated passenger service would return to FEC's rails. If this project succeeds it will be the largest freight railroad to host such services since the early 1980s.

Today, the state of Florida is lauded for its year-round warm temperatures, tropical climate, and pristine white sandy beaches. It is a vacationer's paradise with resorts aplenty and several prominent cities such as Miami, Tampa, Jacksonville, and Tallahassee.

Photos

A rare Florida East Coast E3A, #1002 (originally named "The Champion"), and E7A #1012 layover in Jacksonville during the railroad's late era passenger services that lasted from 1965 until July 31, 1968. American-Rails.com collection.

A rare Florida East Coast E3A, #1002 (originally named "The Champion"), and E7A #1012 layover in Jacksonville during the railroad's late era passenger services that lasted from 1965 until July 31, 1968. American-Rails.com collection.History

However, the state's substantial development began only in the late 19th century with the coming of the railroad. As Dr. George Hilton notes in this book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," there were few in the state prior to the 1880s.

Florida's very first was the mule-powered Tallahassee Railroad, opened in 1837. This 22-mile, five-foot gauge operation connected Tallahassee with the Gulf port of St. Marks.

In the succeeding five decades what were largely three-foot, narrow-gauge systems sprang up to serve small towns across the state.

Overall, the entire peninsula was virtually devoid of human population. The swampy land, brutal tropical heat, mosquitoes, poisonous critters, disease, and alligators made it an extremely inhospitable place which turned most folks away.

At A Glance (1930)

3 Feet (June, 1883 - January 19, 1889) 4 Feet, 8 ½ Inches (January 20, 1889 - Present) | |

Jacksonville - St. Augustine - West Palm Beach - Miami Miami - Homestead - Key Largo - Long Key - Marathon - Key West St. Augustine - Palatka - Bunnell New Smyrna - Benson Junction Maytown - Benson Junction Maytown - Okeechobee - Lake Harbor | |

Nearly the entirety of Florida's eastern coast line lay empty south of St. Augustine and remained this way into the early 20th century.

Its eventual development is thanks exclusively to Henry M. Flagler, an extremely affluent industrialist who had earned his millions through partnership with John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

Early Years

Interestingly, as Harold Mayer points out in his article "Rich Road, Poor Road" from the April, 1941 issue of Trains Magazine, Flagler's eventual Florida East Coast system wasn't the first proposal for a rail line to southern Florida.

In 1870 the Great Southern Railway Company had been chartered to do this very thing, utilizing the Kissimmee River to Lake Okeechobee and then turn east towards the shoreline. It would then have followed the coast to what eventually became Miami and finally strike out for the Keys, terminating at Key West.

In this Florida East Coast publicity photo, new F3's glisten in the Florida sun in Miami during January, 1949. Harry Wolfe photo.

In this Florida East Coast publicity photo, new F3's glisten in the Florida sun in Miami during January, 1949. Harry Wolfe photo.Just as Flagler envisioned decades later the Great Southern planned to reach what was then the state's largest city and develop it as a deep water port.

Ships bound for such locations as South America, Panama, and the West Indies would call there. While some initial construction commenced the entire enterprise never gained considerable backing and was eventually abandoned.

Even the modern FEC's earliest ancestry did not involve Flagler. There were several little, rather unsuccessful operations which eventually wound up as part of the FEC. Its earliest roots trace back to the St. Johns Railway, incorporated on December 31, 1858.

Florida East Coast GP40 #403, GP40-2 #424, and GP9 #654 head south through Titusville, Florida in January, 1981. American-Rails.com collection.

Florida East Coast GP40 #403, GP40-2 #424, and GP9 #654 head south through Titusville, Florida in January, 1981. American-Rails.com collection.The little mule-powered line opened for service in 1859, connecting St. Augustine with Tocoi, a distance of 14.5 miles. The St. Johns operation carried only a very short chapter in the FEC's storied history.

It changed ownership and was eventually purchased by Flagler in 1888 who soon converted the property to standard-gauge (4 feet, 8 1/2 inches).

By this point the railroad was running with steam power but eventually proved superfluous as a nearby road, the St. Augustine & Palatka Railway (built during the mid-1880s and acquired by Flagler's St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway on March 1, 1889), offered a better outlet from St. Augustine to the St. Johns River at East Palatka.

As a result, the St. Johns River Railway was subsequently abandoned during April of 1896. The modern Florida East Coast began with Flagler's acquisition of the Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway.

Logo

This narrow-gauge property started it all for the oil mogul. During the winter of 1883-1884, a 53 year-old retired Flagler spent vacation in historic St. Augustine, regarded as our country's oldest continuously occupied settlement first founded by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés on September 8, 1565.

Flagler was appalled at the lack of transportation services into the region. Jacksonville was the furthest one could travel directly by rail.

To reach St. Augustine, a hamlet of only 2,500 residents, one must board a steamboat to cross the St. Johns River and then catch a train on the narrow-gauge Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway.

The 36-mile rickety ride into the so-called "Ancient City" was less than ideal. Flagler loved the Floridian climate which offered a great escape from the brutal winter weather of the Northeast and he believed a great tourism industry could blossom.

He dubbed it the "American Riviera" in reference to the stunning "French Riviera," found along the country's southern Mediterranean Coast.

However, the Sunshine State required development in hotels, resorts, and transportation services for this to happen. Flagler came out of retirement to do this very thing.

Florida East Coast E9A #1034 works late era passenger service at Jacksonville during the mid-1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Florida East Coast E9A #1034 works late era passenger service at Jacksonville during the mid-1960s. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

For an individual long regarded as a great railroad builder, Flagler actually had little interest in them. However, as the most efficient way to travel they were a simple necessity to serve his future resort business.

According to David P. Morgan's article, "Where Did The Railroad Go That Once Went To Sea?," from the February, 1972 issue of Trains Magazine Flagler purchased the JStA&HR on December 31, 1885.

It would be the catalyst to improve Florida's transportation infrastructure. The JStA&HR dated back to its organization on February 21, 1881.

It opened a 36-mile route from the east bank of the St. Johns River in Jacksonville to St. Augustine during June of 1883. After acquiring the road he converted it to standard-gauge, purchased additional equipment, and generally upgraded the property for modern service.

He then purchased a series of additional narrow-gauge lines to reach Daytona Beach including the Jacksonville & Atlantic (connecting Jacksonville with Jacksonville Beach and Mayport) and St. Johns & Halifax River (East Palatka to Daytona Beach) along with the aforementioned StA&P and St. Johns Railway.

There were two other notable properties which served as branch lines south of Daytona Beach; the Atlantic & Western (New Smyrna Beach to Blue Springs) and Atlantic Coast, St. Johns & Indian River Railway (Enterprise Junction to Titusville via Maytown).

On January 20, 1890 a bridge was completed across the St. Johns River establishing direct service into Jacksonville.

During the fall of 1892 Flagler's growing rail empire underwent a corporate name change when all properties involved became the Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Indian River Railway. This name itself was short-lived; on September 9, 1895 Flagler's railroads became collectively known as the Florida East Coast Railway.

As this was ongoing other events were transpiring simultaneously. He launched his resort empire, beginning with the new Ponce de Leon hotel in St. Augustine. The facility opened in January of 1888 and was followed by the nearby Alcazar in 1889.

He also purchased existing hotels including the Casa Monica in St. Augustine as well as the Hotel Ormond in nearby Ormond Beach. As the railroad gradually extended its way southward additional resorts followed.

Even during the late 19th century the only notable settlement south of St. Augustine was the tiny hamlet of Daytona Beach; incorporated in July of 1886 it contained only a few hundred residents. Beyond that, white sandy beaches and open ocean was all one would encounter to Key West.

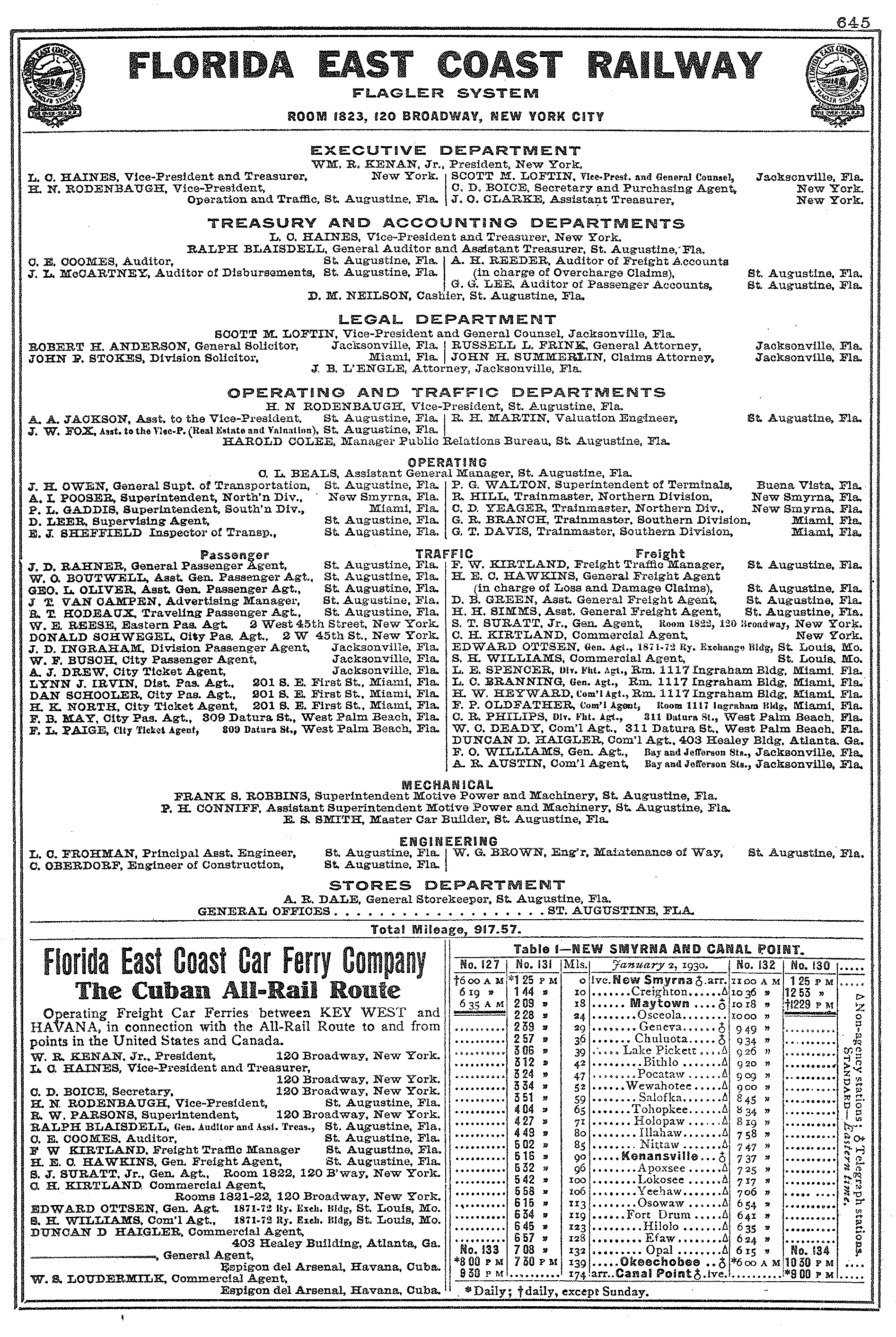

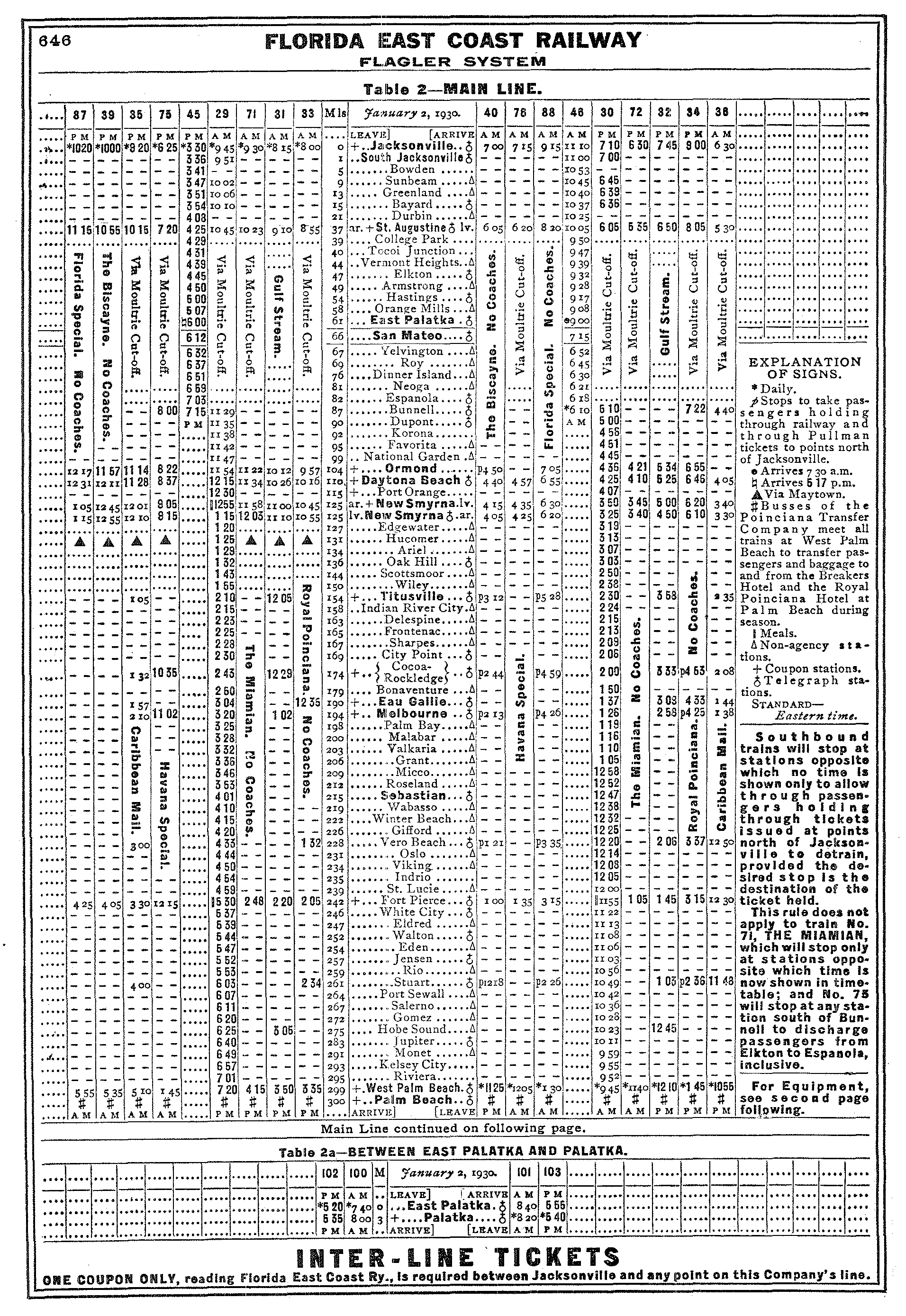

Schedule and Timetables (1930)

Following the FEC's creation, Flagler continued his southward push reaching New Smyrna Beach in 1892, Cocoa in 1893, West Palm Beach in 1894, and finally Miami on April 15, 1896. The main line from Jacksonville now extended 366 miles.

What followed were a series of additional resorts: the Royal Poinciana opened during February of 1894 in Palm Beach followed by the Palm Beach Inn during January of 1896 (renamed The Breakers in 1901); and near Miami the Royal Palm Hotel opened in Biscayne Bay on January 16, 1897.

He also acquired the Hotel Biscayne soon after the Royal Palm opened providing for a second establishment at Miami.

The last resort built was located at the northern end of the railroad. Just east of Jacksonville he constructed The Continental at Atlantic Beach which opened in 1901.

This facility proved the least successful and was later destroyed by fire in 1919. Most of the other resorts were gone by the depression era. However, they proved invaluable in the FEC's growth as well as the state's population explosion during the 1920s.

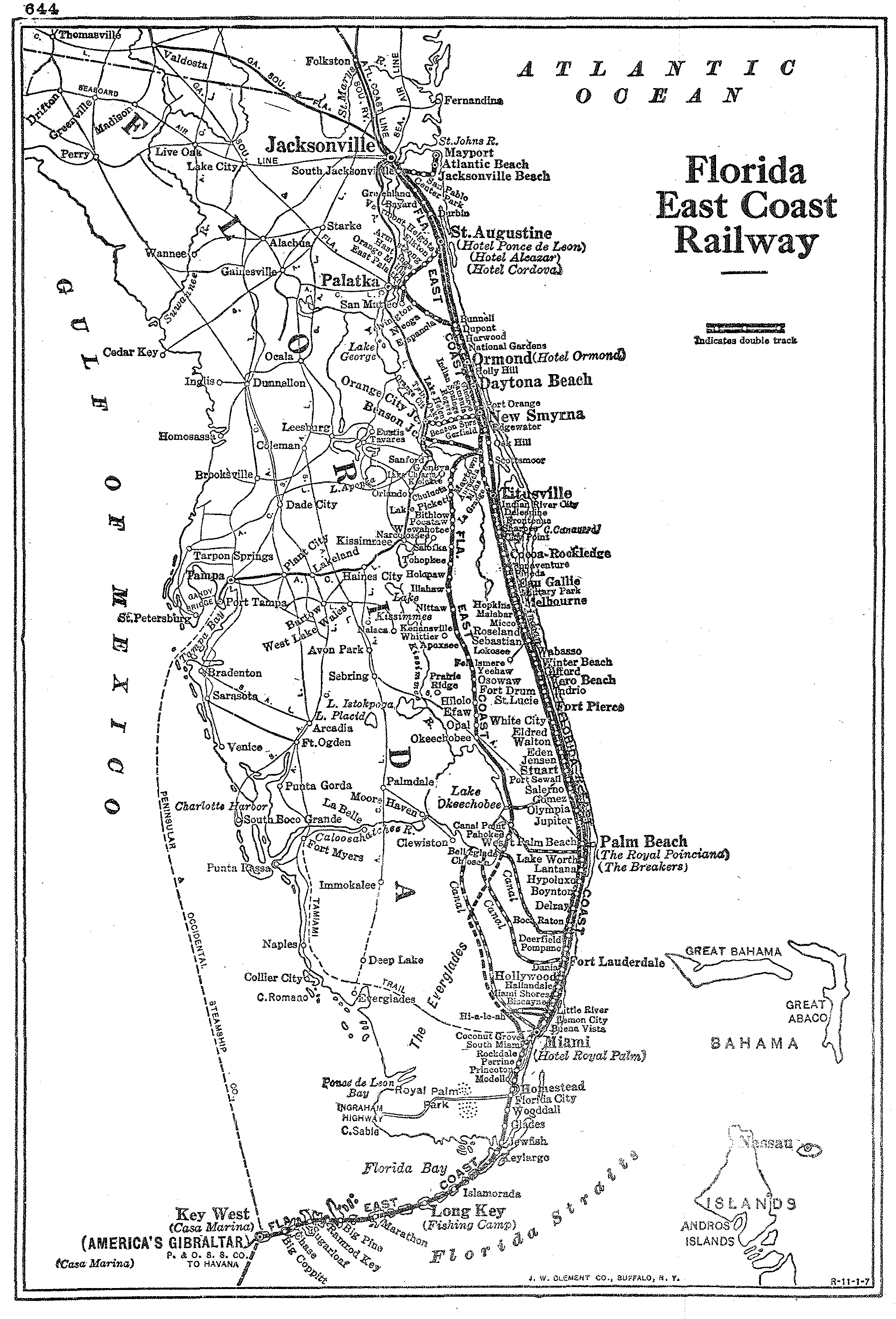

System Map (Pre-1935)

Beyond Flagler's hotel empire were his land companies. Like many states, Florida offered land grants to railroads for every mile of track laid.

Flagler acquired some of this acreage by purchasing the systems described above while other property was added as he pushed towards Miami.

In his book, "Speedway To Sunshine: The Story Of The Florida East Coast Railway," Seth Bramson notes that in all, Flagler accumulated 2.04 million acres from the state.

While the businessman used these assets for financial gain and growing his railroad he also utilized them in developing Florida's industrial and agricultural businesses along the east coast. Finally, there were the steamship lines.

In 1897 Flagler launched the FEC Steamship Company, which initiated service between Miami and Nassau in early 1898. On July 1, 1900 the operation merged with the Plant Steamship Company creating the Peninsular & Occidental Steamship Company.

The P&O remained a part of the Florida East Coast into the 1960s although its greatest importance was during the period in which the Key West Extension operated.

Key West Extension

During the Extension's time in service the P&O regularly dispatched ships to and from Havana.

In addition, a car ferry service known as the Florida East Coast Car Ferry Company, provided freight connections to Cuba; it operated via Key West until the horrendous Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 destroyed the rail line.

After that time it dispatched from Port Everglades until World War II and from Palm Beach after the war until ceasing all operations in 1960. The Key West Extension, officially known as the Florida Overseas Railroad, was the final leg of Flagler's great railroad empire.

He believed Key West would develop into a busy deep water port (then containing about 20,000 residents) as well as a trade route with Cuba and Latin America following the Panama Canal's opening (then under construction).

He also thought the port would act as a vital refueling (coal) point for steam ships entering or exiting the canal. Following a series of surveys, company engineers concluded a railroad could, indeed be constructed across the Keys and into Key West.

An SD40-2, #703 (ex-Union Pacific #3698), and SD70M-2 are seen here at Bowden Yard in Jacksonville, Florida on April 8, 2013. Warren Calloway photo.

An SD40-2, #703 (ex-Union Pacific #3698), and SD70M-2 are seen here at Bowden Yard in Jacksonville, Florida on April 8, 2013. Warren Calloway photo.The railroad made an official announcement construction of the project had commenced in April, 1905. The line had already reached Homestead a year earlier in 1904 and proceeded steadily southward after that time. By late 1905 work was underway from both directions.

The extension covered a total of 156 miles via Miami. The elderly Flagler nearly bet everything on the railroad's gamble to reach Key West.

The Florida Overseas Railroad was built to the highest construction standards, often utilizing concrete viaducts to bridge the distances across the tiny patches of land. At one time or another the company employed more than 4,000 men.

Unfortunately, costs were driven up by three hurricanes which struck the Keys during construction. The Extension required more than two-dozen bridges with the largest being Seven Mile Bridge, connecting Marathon with Big Pine Key. It took Flagler and the FEC seven years but the route was officially completed on January 21, 1912.

A day later the 82-year-old Flagler arrived in Key West aboard his private business car (he passed away a year later on May 20, 1913).

Most had scoffed at the idea such a railroad could ever be built, calling it "Flagler's Folly." However, once completed it was hailed as the "Eighth Wonder of the World". Overall the project had cost roughly $49 million.

Unfortunately, the Extension never did reach its full potential. Despite Flagler's belief Key West neither developed into a major port nor a refueling stop. As sailing vessels were able to travel further and further between stops the resort town lost its status as a maritime resupply hub.

Peak Years

The 1920s proved the greatest period in the Florida East Coast's storied history. It all began slightly before the decade dawned when construction commenced on the railroad's last great expansion, the Okeechobee Branch.

This line, which ran south from Maytown, near New Smyrna Beach, was meant to open Florida's interior to agricultural development while generating additional freight along the FEC's network. Work on the line began in February of 1911 and was finished to Okeechobee in early 1915, a distance of 122 miles.

An additional spur, running along the eastern shore of Lake Okeechobee, was finished to Lake Harbor in 1929 offering an interchange with the Atlantic Coast Line. Following this project the FEC maintained a network of just over 850 miles.

New residents poured into the Sunshine State throughout the 1920s and the railroad was eventually overwhelmed. It could simply not keep up with the incredible demand forcing it to take the unprecedented step of issuing an embargo on some freight movements in 1925 until the situation improved.

System Map (1969)

There were eight passenger trains running in each direction between Miami and Jacksonville (service peaked briefly at fourteen trains each way) while freight consisted of agriculture, lumber, naval stores, manufactured goods, and other products.

In 1926 it handled an incredible 1 billion ton-miles of business with total revenues of $29.4 million, an increase of more than $13 million in only three years! The FEC frantically attempted to keep pace by purchasing larger locomotives including 4-6-2's, 4-8-2's, 2-8-2's, and switchers in various arrangements, along with other equipment.

It spent $45 million to double-track its entire main line between Jacksonville and Miami (launched in 1924 and completed in 1926 the project included block signaling) and completed the Moultrie Cutoff between St. Augustine and Bunnell.

The 29-mile route eliminated the circuitous old routing heading southwest to East Palatka and then southeast to Bunnell, shaving 20 miles in the process. Next, all main line rail was upgraded from 70 to 90 pounds for heavier and longer trains.

Finally, in 1926 an additional $21 million dollars was spent to improve operations. Alas, as the great boom began it ended just as quickly. A series of events transpired during a decade's span that witnessed the company falling into bankruptcy and its fabled Key West Extension abandoned.

Decline

As Mr. Mayer points out in his article, the FEC's traffic declines began at the end of 1926 and accelerated through 1927. It earned slightly less than $18 million that year coinciding with a new competition at Miami as the Seaboard Air Line opened its own route to the growing port city.

In 1928 things worsened as revenue declined to under $14 million. Then, the great stock market crash of 1929 occurred. At first, the Florida East Coast weathered the storm despite showing a loss that year.

However, as the situation worsened the road entered receivership on September 1, 1931. Revenues dipped even further in 1933 to just $7 million. To offset additional losses the FEC abandoned many of its secondary branch lines during that decade.

Then, Mother Nature added a knockout blow in 1935; the great Labor Day Hurricane hammered the Keys with winds clocked at 200 mph.

The natural disaster destroyed around 42 miles of the Key West Extension. Mired in bankruptcy the railroad elected to abandon the line instead of rebuild; from near Florida City to Key West the right-of-way (everything except the Trumbo Island Terminal which was sold to the government) was handed over to the state for just $640,000.

The line was so well built that much of the remaining pier infrastructure was used for Florida's Highway 1, a modern version of which now connects the entire Key West island system to the state’s mainland.

In truth, even before the hurricane the Extension was in decline, having never developed into the great port Flagler had anticipated.

Instead, Miami was claiming this title and Key West shrank; by 1930 its population was only 13,000. Despite the Extension's incredible beauty there were only a few passenger trains operating south of Miami. Freight paid the bills and this business was also drying up.

The primary movements consisted of sealed cars moving through the port, Cuban cigars (which had shifted to the port of Tampa to reduce rail rates), fresh water for the Keys, some agriculture, and various less-than-carload movements.

Compounding the problem was Key West's geography; the island contained only a finite amount of land for business development. It is quite likely that had the hurricane not happened the Extension would have been abandoned at some point in the future anyway.

Florida East Coast 0-8-0 #270, a 1926 product of Alco, sits on the ready track at West Palm Beach, Florida on December 15, 1953. John Krave photo.

Florida East Coast 0-8-0 #270, a 1926 product of Alco, sits on the ready track at West Palm Beach, Florida on December 15, 1953. John Krave photo.By 1940 the FEC had been reduced to just 679 route miles. The following decades were an up and down struggle as it tried to escape receivership and increase revenues. Its first new diesels arrived in late November of 1939 in the form of Electro-Motive's sleek E3A model for passenger services (#1001-1002).

Between late 1940 and early 1942 a trio of similar E6A's were acquired (#1003-1005). Following World War II a steady supply of new EMD products were added to FEC's roster until steam was gone entirely by 1959.

On April 1, 1947 the railroad began operating its new branch to Lake Okeechobee via Fort Pierce and Marcy to reach the ACL connection at Lake Harbor.

This eliminated much of the line north of Okeechobee, which contained sparse traffic. On January 1, 1961 the FEC formally exited receivership and came under the ownership of the St. Joe Paper Company in a deal negotiated by Edward Ball. The company's future appeared bright with a new direction and stronger revenues.

Labor Strike

However, it had lasted but a few years when a nasty strike by FEC's operating unions was launched on January 23, 1963. It paralyzed the railroad and eventually resulted in all passenger services discontinued.

These trains returned briefly when the FEC was required to reinstate service between Jacksonville and North Miami; launched again on August 2, 1965 they lasted only until July 31, 1968. The union strike, itself, ultimately failed as the FEC was able to continue running its trains via management crews.

The unions were eventually decertified by the National Labor Relations Board and the FEC permanently cut down its crew sizes from five to just two (conductor and engineer).

Prior to the 1963 labor unrest the railroad had maintained a payroll of 2,100 employees. After everything had settled out these numbers were cut to less than 1,100 by the early 1970s.

The railroad made great strides in reducing its excess physical plant and operating expenses at this time while finding a new, healthy form of freight, intermodal.

Carrying an ever-increasing numbers of trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) and container-on-flatcar (COFC) business, in addition to automobiles, the FEC's revenues surged to over $100 million by 1980. Today, its traffic has remained relatively unchanged.

Today

The railroad is and has always been an independent company. In 2007 it was purchased by Fortress Investment Group, LLC, which oversaw the railroad and other businesses interests.

This company had also owned RailAmerica, a short line conglomerate, which was designated operator of the FEC in March of 2008.

For a time this change resulted in the the Flagler System losing much of its identity with equipment repainted in RA's standard red, white and blue livery.

However, not long after the announcement Fortress reversed its stance and kept the FEC as a separate, independent portfolio outside of the RailAmerica network (in 2012 Genesee & Wyoming acquired the RA family of short lines).

Its ownership persisted for a decade when rumors began in late March of 2017 that Mexico's largest railroad, Ferromex, was looking to acquire the FEC.

Passenger Trains

City of Miami: (Chicago - Birmingham - Miami)

Dixie Flagler: (Chicago - Miami)

Havana Special: (New York - Miami - Key West/Havana)

South Wind: (Chicago - Louisville - Miami)

These talks turned out to be true when Grupo Mexico Transportes S.A. de C.V., which owns Ferromex, made the official announcement on March 28th.

According to Grupo: "'The acquisition of FEC is an important strategic addition to our North American transportation service offering,' Alfredo Casar, president and CEO of GMéxico Transportes, says.

'We are excited to welcome FEC to our transportation team as we work together to provide safe, reliable and efficient rail and trucking services to our customers.'"

Diesel Roster (Acquired New)

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number(s) | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD70M-2 | 100-107 | 2006-2008 | 8 |

| SW9 | 221-228 | 1952-1953 | 8 |

| SW1200 | 229-235 | 1953-1954 | 7 |

| GP40 | 401-410 | 1971 | 10 |

| GP40-2 | 411-434 | 1972-1986 | 25 |

| F3A | 501-508 | 1949 | 8 |

| GP38-2 | 501-511 | 1977-1978 | 11 |

| F3B | 551-554 | 1949 | 4 |

| FP7 | 571-575 | 1951 | 5 |

| BL2 | 601-606 | 1948 | 6 |

| GP7 | 607-621 | 1952 | 15 |

| GP9 | 651-676 | 1954-1957 | 26 |

| E3A | 1001-1002 | 1939 | 2 |

| E6A | 1003-1005 | 1940-1942 | 3 |

| E7A | 1006-1022 | 1945-1947 | 17 |

| E9A | 1031-1035 | 1955 | 5 |

| E6B | 1051 | 1942 | 1 |

| E7B | 1052-1054 | 1945 | 3 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Numbers | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES44C4 | 800-823 | 2014 | 24 |

Steam Roster

| Road Numbers | Type | Known Builder | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-27 | American | Baldwin | 4-4-0 |

| 28-39 | Ten-Wheeler | Unknown | 4-6-0 |

| 40-44 | Ten-Wheeler | Baldwin | 4-6-0 |

| 45-64 | Atlantic | Alco/Schenectady | 4-4-2 |

| 65-74, 77-136 | Pacific | Alco/Schenectady | 4-6-2 |

| 141-150 | Pacific | Alco/Richmond | 4-6-2 |

| 151-157 | Pacific | Alco/Schenectady | 4-6-2 |

| 75-76 (201-202), 137-140 (203-206), 158-160 (207-209) | Switcher | Alco/Schenectady | 0-6-0 |

| 210-214 | Switcher | Alco/Richmond | 0-6-0 |

| 251-279 | Switcher | Alco/Richmond | 0-8-0 |

| 301-315 | Mountain | Alco/Richmond | 4-8-2 |

| 401-452 | Mountain | Alco/Schenectady | 4-8-2 |

| 701-715 | Mikado | Alco/Schenectady | 2-8-2 |

| 801-823 | Mountain | Alco/Schenectady | 4-8-2 |

Here, SD70M-2 #107 (wearing a livery when the railroad was owned by RailAmerica) leads autoracks near Jacksonville, Florida on March 29, 2014. Warren Calloway photo.

Here, SD70M-2 #107 (wearing a livery when the railroad was owned by RailAmerica) leads autoracks near Jacksonville, Florida on March 29, 2014. Warren Calloway photo."Brightline" Service

Also of note was the announcement during the summer of 2012 that the Florida East Coast plans to host passenger trains between Miami and Cocoa.

The goal, called "All Aboard Florida" is quite ambitious; in addition to FEC's line it will build a brand new 40-mile, double-tracked extension from Cocoa to Orlando utilizing the median of State Road 528.

The cost of the project is slated at $1.5 billion but is to be financed by all private investments. The service, officially known as Brightline, will operate the 240 corridor in around three hours with equipment provided by Siemens.

In what could certainly be described as high speed operation it is designed to operate up to at least 79 mph. There are also plans to operate at speeds reaching 110 mph between West Palm Beach - Cocoa and 125 between Cocoa - Orlando.

Initially, it was believed operations could begin in 2015. However, these have now been pushed back; Miami to West Palm Beach is expected to launch sometime in 2017 and reach Orlando by 2018. If successful it will be interesting to see if other large freight railroads take notice.

Recent Articles

-

Ohio Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 10:07 PM

The Ohio Rail Experience's Quincy Sunset Tasting Train is a new offering that pairs an easygoing evening schedule with a signature scenic highlight: a high, dramatic crossing of the Quincy Bridge over… -

Texas Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 02:07 PM

Texas State Railroad's “Pints In The Pines” train is one of the most enjoyable ways to experience the line: a vintage evening departure, craft beer samplings, and a catered dinner at the Rusk depot un… -

Michigan's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:47 PM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:39 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Florida Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 01:25 PM

Among the Sugar Express's most popular “kick off the weekend” events is Sunset & Suds—an adults-focused, late-afternoon ride that blends countryside scenery with an onboard bar and a laid-back social… -

Illinois Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 09, 26 12:04 PM

Among IRM’s newer special events, Hops Aboard is designed for adults who want the museum’s moving-train atmosphere paired with a curated craft beer experience. -

Tennessee Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:46 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Wisconsin Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:35 AM

The East Troy Railroad Museum's Beer Tasting Train, a 2½-hour evening ride designed to blend scenic travel with guided sampling. -

California Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:33 AM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Colorado BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Feb 08, 26 10:32 AM

One of the most popular ways to ride the Leadville Railroad is during a special event—especially the Devil’s Tail BBQ Special, an evening dinner train that pairs golden-hour mountain vistas with a hea… -

New Jersey Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:23 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Minnesota Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:21 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train, -

New Mexico Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:18 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Michigan Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 11:13 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Oregon Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 10:08 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 07, 26 09:22 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train!