Central Vermont Railway: Map, Logo, Timetable, Rosters

Last revised: November 18, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Central Vermont Railway was another of the fabled New England lines. It sliced north to south across the heart of the region, linking Montreal, Quebec with southern Connecticut at New London via St. Albans, Middlesex, Windsor, and Northfield (Massachusetts).

While the CV did have money troubles at various times, resulting in its once vast network split up in the late 19th century, the railroad was a mostly profitable operation ferrying traffic to and from the U.S. and Canada. It spent most of the 19th century, and into the 20th, battling the Rutland Railroad, a system it once controlled.

After the Canadian National Railway (which had controlled the CV for many years through a subsidiary known as the Grand Trunk Railway) became a private company in 1995 it sold the property in an attempt to streamline operations.

Today, most of the former CV trackage remains in use as the New England Central Railroad, part of Genesee & Wyoming's family of short lines.

Photos

Central Vermont GP9 #4925 has southbound train #76 stopped at Essex Junction, Vermont on February 11, 1961. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Central Vermont GP9 #4925 has southbound train #76 stopped at Essex Junction, Vermont on February 11, 1961. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.History

What became Vermont's two notable railroads, the Rutland and Central Vermont, can trace their unofficial heritage all of the way back to the early 19th century when the state's northern regions, and those of New York, were attempting to improve trade and transportation to that part of the country.

At the time, canals were all the rage although these waterways were expensive to build and their geographical location of northern New England meant they would be frozen for nearly half the year.

The hope for towns such as Ogdensburg, New York and Rutland, Vermont (even Montreal) was to see a canal eventually constructed to the important New England port of Boston.

However, proper funding was never attained and proponents could not figure out an economic means of scaling the formidable Green Mountains.

By the 1830s, railroads were fast becoming the future of transportation, soon to make canals obsolete. Promoters saw this new technological invention as the means of finally opening trade to southern New England.

At A Glance

Montreal, Quebec - St. Albans - White River Junction, Vermont White River Junction, Vermont - East Northfield, Massachusetts (Boston & Maine trackage rights, 1900-1988) East Northfield - New London, Connecticut East Northfield - Greenfield, Massachusetts Montpelier Junction - Montpelier - Barre, Vermont Essex-Burlington Junction - Burlington, Vermont St. Albans - Richford, Vermont St. Albans - Rouses Point, Vermont | |

Two businessmen, Charles Paine and Timothy Follett, eventually stepped forward with proposals that carried the potential and financial backing to actually see such projects completed.

The former wanted to construct a rail line following Vermont's White River near the New Hampshire border (White River Junction) until reaching a location near Montpelier via Northfield.

From that point, rails would turn west following the Onion River (now known as the Winooski River) and reaching Lake Champlain at Burlington. This system eventually became the Central Vermont Railway.

The latter believed a railroad would gain more traffic by heading roughly west from the Connecticut River, linking to Mount Holly, and turning due north to Rutland before terminating at Burlington along the eastern shores of the lake. In the case of Mr. Follett, he also saw his proposal as a way to bolster his steamship business on the lake.

Logo

According to Jim Shaughnessy's, "The Rutland Railroad," the two, which grew into bitter rivals, finally received authorization to construct their respective corridors when the Vermont general assembly passed a bill in October of 1843 to incorporate the Vermont Central Rail Road and Champlain & Connecticut River Rail Road.

Follett's company changed its name as the Rutland & Burlington Railroad in November of 1847 and following bankruptcy became the Rutland Railroad on July 9, 1867.

Scott Hartley points out in his article, "Central Vermont...A Survivor," from the February, 1991 issue of Trains Magazine that groundbreaking on the VC began in 1845. However, a few years had passed before the first section opened between Bethel, Vermont and White River Junction on June 26, 1848.

Later that year, Paine's hometown of Northfield saw its first train on October 10th. Into 1849 the railroad saw many accomplishments as it quickly expanded north and south; on February 13th it opened to Windsor, Vermont following the Connecticut River roughly 14 miles south of White River Junction.

In addition, later in the year it opened to Montpelier on June 10th, via Montpelier Junction (due to rough terrain, the railroad was forced to reach the capital via a branch instead of a through main line as it had originally intended). Finally, it reached Burlington by the end of the year on December 31st.

The opening of the Vermont Central was only the beginning of the Rutland & Burlington's problems; throughout the 19th century the VC edged the R&B at virtually every turn as it grew larger and larger across New England.

The Vermont & Canada Railroad was chartered on October 31, 1845 by John Smith who began working with Paine to establish through rail service from Burlington further north to St. Albans/Swanton, and then west to Rouses Point, New York.

At this point a connection was established with the Northern Railroad of New York, which later became the Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain, eventually acquire by the Rutland in 1901. It completed a connection with the VC in 1850 at a location known as Essex Junction, a few miles east of Burlington.

This odd move meant the state's largest city would be served only by a branch and the reasoning was entirely trivial; to stifle the R&B and prevent it from establishing a useful connection.

The V&C also formed a subsidiary in 1860 known as the Montreal & Vermont Junction Railway, which opened later that decade from Swanton to St. Johns, Quebec where it connected with the Grand Trunk Railway (later Canadian National) into Montreal.

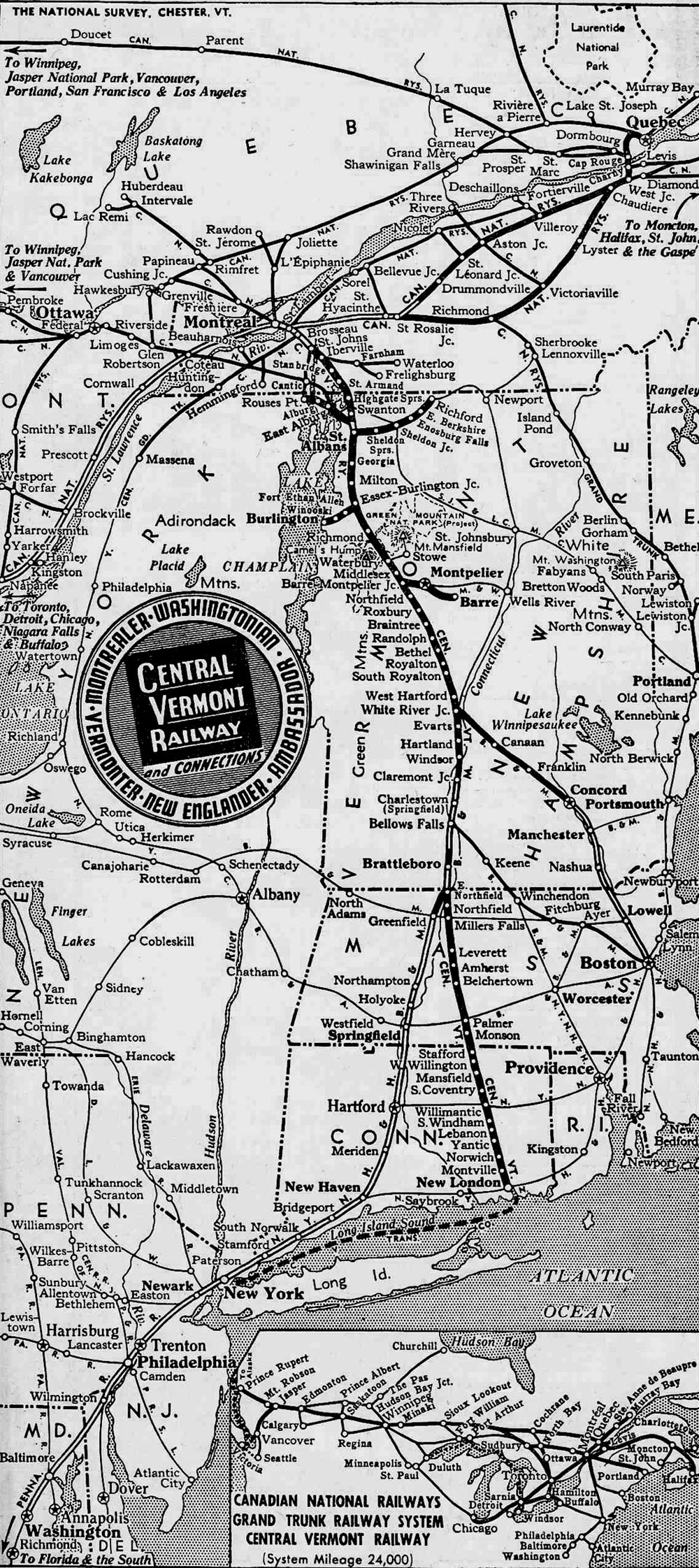

System Map (1941)

On August 24, 1849 the Vermont Central formally leased the V&C and the latter was completed a few years later in 1851. Unfortunately, the silliness at Burlington persisted for years resulting in duplicate facilities, trackage, and Paine's stubbornness to not connect his road with the R&B.

Paine would lose control of his railroad in 1852 when one-time ally John Smith acquired the company through a devious contract arrangement.

However, Smith was no more interested in working with the R&B than his predecessor. Smith's efforts worked in eventually driving the R&B into bankruptcy at around the same time, which resulted in Follett also exiting the business.

The growing discontent between the two railroads, however, finally reached a crescendo in 1858 when a fed up state legislature, spurred by an irritated public, forced cooperation at Burlington via an interchange and reasonable schedules.

There was continued bickering but by 1860 the connection was complete and the hatred between the two subsided over time.

A Central Vermont 2-8-0 leads a northbound general manifest over a wood pile trestle at Smith Cove along the Thames River, near Quaker Hill, Connecticut, circa 1952. American-Rails.com collection.

A Central Vermont 2-8-0 leads a northbound general manifest over a wood pile trestle at Smith Cove along the Thames River, near Quaker Hill, Connecticut, circa 1952. American-Rails.com collection.Following Smith's death in 1858 his son, John Gregory Smith, took control of the Vermont Central and began expanding its reach. Its northern connections are highlighted above while its southern extensions began at around the same time.

Mr. Hartley points out that after 1861 the VC grew largely through either direct acquisition or takeover of other lines; most notable here was rival Rutland, which it formally leased on December 30, 1870.

Under the direction of John Page, who led the Rutland from 1868 until 1883, it had blossomed into a serious VC competitor and Smith had grown vexed of this longtime rival. The VC's other additions included:

- The Sullivan County Railroad from Windsor to Bellows Falls (an 1863 acquisition by Smith).

- Vermont Valley between Bellows Falls and Brattleboro (leased by the Rutland in May of 1865).

- A segment of the Vermont & Massachusetts (leased by the Rutland on December 1, 1870) which extended the VC to Grout's Corners, Massachusetts (Millers Falls).

- Finally, the New London Northern Railroad (also acquired by the Rutland at around the same time as the Vermont & Massachusetts).

All of these railroads pushed service to New London, Connecticut, which even reached New York City indirectly via steamship service across the Long Island Sound.

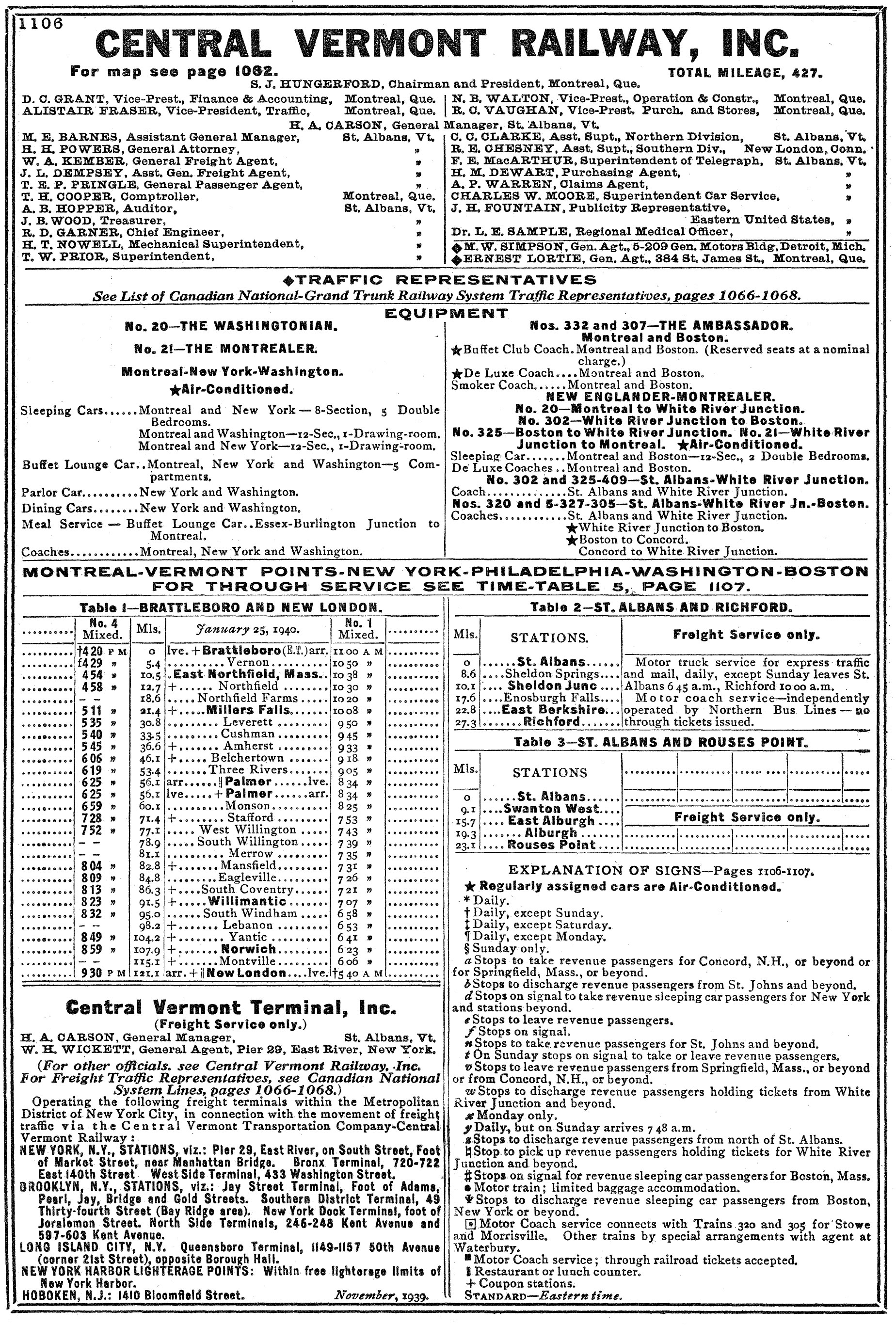

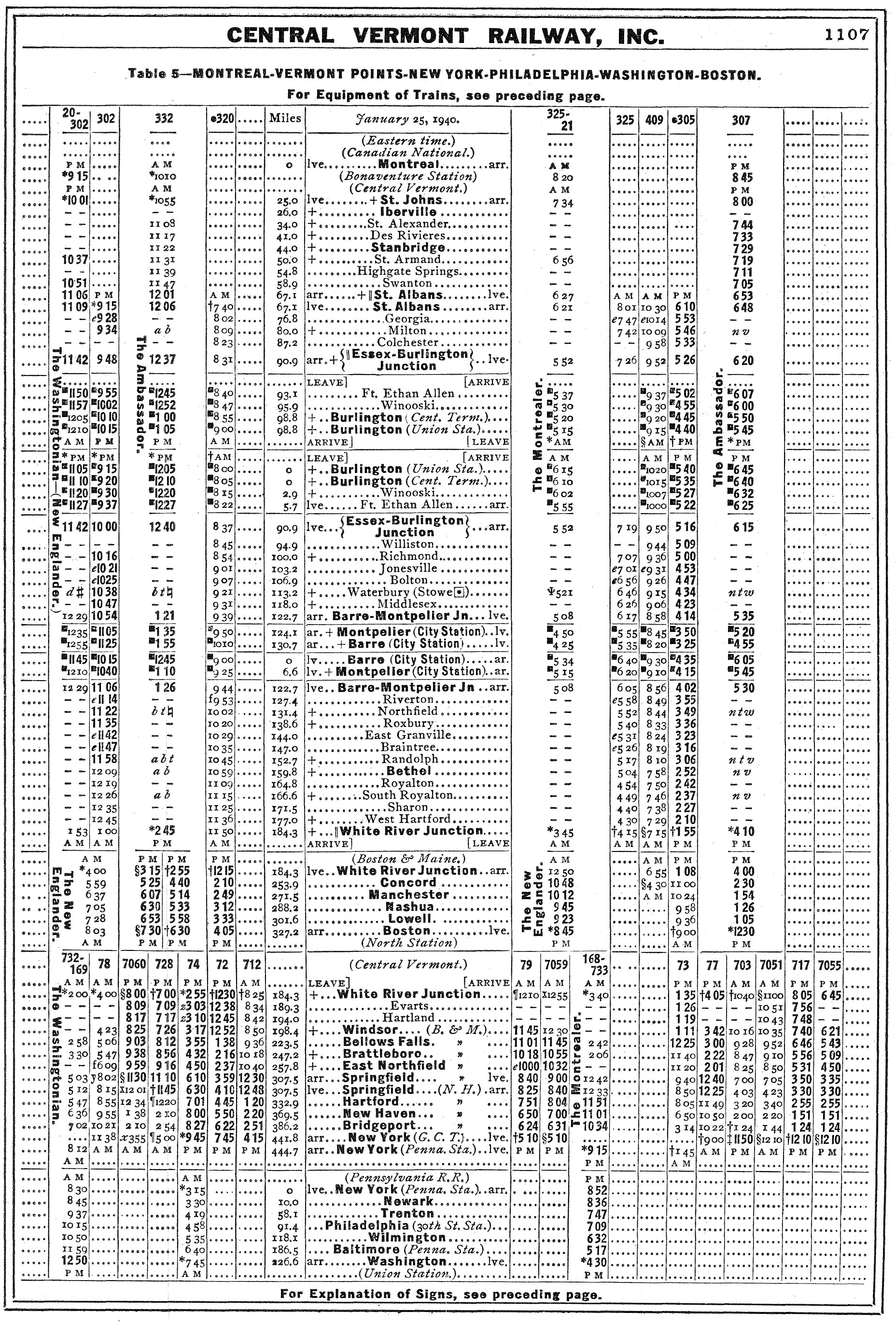

Timetables (1940)

In 1876 the VC discontinued its lease of both the Sullivan County and Vermont Valley railroads, acquiring trackage rights instead over the Connecticut River Railroad (later Boston & Maine). From 1900 until 1988 the-then Central Vermont utilized such rights from East Northfield, Massachusetts to White River Junction.

Oddly this arrangement always left the CV's lines in Vermont and those in Massachusetts/Connecticut disconnected. The younger Smith continued his quest for domination across New England as his railroad took control of the 118-mile Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain running between Ogdensburg, New York, along the St. Lawrence River, and Rouses Point during March of 1870.

Mr. Shaughnessy notes that upon the takeover, the Vermont Central owned the largest railroad in New England, operating a network of over 900 miles while also controlling two steamship lines. Unfortunately, this proved the zenith of the Vermont Central as it slowly declined during the remainder of the 19th century.

It seems the lease of the Rutland proved a fatal mistake due to its high rental costs, lack of sufficient traffic, and the unforeseen financial Panic of 1873 which thrust the country into a recession.

A railfan looks on as Central Vermont 2-8-0 #465 simmers away at Amherst, Massachusetts with train #2, the southbound run from Brattleboro, Vermont to New London, Connecticut in the fall of 1945. American-Rails.com collection.

A railfan looks on as Central Vermont 2-8-0 #465 simmers away at Amherst, Massachusetts with train #2, the southbound run from Brattleboro, Vermont to New London, Connecticut in the fall of 1945. American-Rails.com collection.As a result, the VC dropped its interest in the Whitehall & Plattsburgh and Montreal & Plattsburgh as well as the steamship Oak Ames working Lake Champlain. It still entered reorganization proceedings that year and emerged as the Central Vermont Railroad with Smith maintaining his presidency.

The newly-named system also continued to retrain control of the Rutland and O&LC, renewing its lease in 1890. In 1891, John Gregory Smith's son, Edward Curtis, took over as president but his tenure was short-lived.

The Central Vermont continued to deal with high rental costs and subsidiaries that did not warrant a great return on their investment. In 1893 the country was plunged into another financial panic, thrusting the CV into bankruptcy during March of 1896.

It emerged in 1898 as the Central Vermont Railway having dropped all ties to the Rutland and O&LC. The new company was soon acquired by the Grand Trunk Railway, owning two-thirds of its stock.

The GT never relinquished control of the CV and became part of Canadian National Railways in 1922 when the government nationalized a transcontinental network comprising several subsidiaries.

After this time it carried a largely trunk-line status only, operating 325 miles from Montreal to New London in addition to short branches reaching Rouses Point and Richford.

Prior to World War I, however, the Central made one last attempt to expand and reacquire a direct routing to southern New England. Under the direction of President Charles Hays the Southern Vermont Railway was formed to rid the need for trackage rights over the B&M; in addition, a nearly 200-mile extension commenced from Palmer, Massachusetts to Providence, Rhode Island, which would have provided the CV with a major port and interchange connections.

Alas, fate stepped in and Hays perished in the sinking of the Titanic on April 14, 1912. As a result of severe flooding during November of 1927 the railroad again fell into bankruptcy but soon emerged in 1929 as the Central Vermont Railway, Inc.

While the Central Vermont was no longer independent it did keep much of its corporate identity and was run as a separate railroad from the rest of the CN system. In 1932, Edward Smith resigned his post as president, ending 70 years of the family name leading the company.

Passenger Trains

Ambassador/New Englander: (Boston - Montreal)

Montrealer/Washingtonian: (Washington - New York - Montreal)

As the grip of the Great Depression eased the railroad became a relatively successful arm of the CN network until the postwar period. It moved a wide range of freight from general merchandise and furniture to milk, agriculture, and various types of less-than-carload traffic.

It also worked closely with the Boston & Maine/New Haven to carry through services to and from Montreal such as the Ambassador/New Englander (Boston - Montreal) and Montrealer/Washingtonian (Washington - New York - Montreal).

The CV did its part to keep up with the traffic demands of World War II but slowly declined after this time. Parent Canadian National abandoned its Quebec trackage following war in favor of its own rails north of Alburgh, Vermont. In 1958 it sold off all trackage east of Montpelier Junction and abandoned the 8.3 miles from Alburgh to Rouses Point.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Class | Serial Number | Retirement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1859-1860 | - | 80747, 80748 | 9/1954 | Steam-generator equipped. | |

| 3041-3042 | - | 80745-80746 | 9/1954 | ex-GTW #1861-1862 | |

| RS11 | 3600 | MR-18a | 81934 | 8/1956 | ex-DW&P #3600 |

| RS11 | 3601 | MR-18a | 81935 | 8/1956 | ex-DW&P #3601 |

| RS11 | 3602 | MR-18a | 81936 | 8/1956 | ex-DW&P #3602 |

| RS11 | 3603 | MR-18a | 81937 | 1956 | ex-DW&P #3603 |

| RS11 | 3604 | MR-18a | 81938 | 8/1956 | ex-DW&P #3604 |

| RS11 | 3605 | MR-18a | 81939 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3605 |

| RS11 | 3606 | MR-18a | 81940 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3606 |

| RS11 | 3607 | MR-18a | 81941 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3607 |

| RS11 | 3608 | MR-18a | 81942 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3608 |

| RS11 | 3609 | MR-18a | 82026 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3609 |

| RS11 | 3610 | MR-18a | 82027 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3610 |

| RS11 | 3611 | MR-18a | 9/1956 | 82028 | ex-DW&P #3611 |

| RS11 | 3612 | MR-18a | 82029 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3612 |

| RS11 | 3613 | MR-18a | 82030 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3613 |

| RS11 | 3614 | MR-18a | 82031 | 9/1956 | ex-DW&P #3614 |

| S2 | 7918-7919 | MS-10a | 69653-69654 | 1/1942 | Renumbered 8094-8095. Transferred to GTW in 10/1967. |

| S4 | 8015, 8027 | MS-10j | 79227, 80467 | 10/1951, 5/1953 | - |

| S4 | 8080-8081 | MS-10j | 81400-81401 | 9/1955 | - |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Class | Serial Number | Completion Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW1200 | 1509-1511 | GR-12j | 22827-22828, 25743 | 4/1957, 3/1960 | ex-GTW #1269-1270, #1511 |

| GP18 | 3602 | - | 26934 | 10/1961 | ex-Rock Island #1345 |

| GP18 | 3614 | - | 25451 | 1/1960 | ex-Rock Island #1334 |

| GP9 | 4442 | GR17d | 21449 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1768 |

| GP9 | 4443 | GR17d | 21450 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1769 |

| GP9 | 4444 | GR-17d | 21451 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1770 |

| GP9 | 4445 | GR-17d | 21452 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1771 |

| GP9 | 4446 | GR-17d | 21453 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1772 |

| GP9 | 4447 | GR-17d | 21454 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1773 |

| GP9 | 4448 | GR-17d | 21455 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1774 |

| GP9 | 4449 | GR-17d | 21456 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1775 |

| GP9 | 4450 | GR-17d | 21457 | 5/1956 | ex-GTW #1776 |

| GP9 | 4547 | GR-17j | 22836 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GP9R #4602 in 1989. |

| GP9 | 4548 | GR-17j | 22837 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4549 | GR-17j | 22838 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GP9R #4623 in 1991. |

| GP9 | 4550 | GR-17j | 22839 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GP9R #4607 in 1989. |

| GP9 | 4551 | GR-17j | 22840 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GP9R #4605 in 1989. |

| GP9 | 4552 | GR-17j | 22841 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4553 | GR-17j | 22842 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4554 | GR-17j | 22843 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4555 | GR-17j | 22844 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4556 | GR-17j | 22845 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4557 | GR-17j | 22846 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4558 | GR-17j | 22834 | 3/1957 | ex-GTW #4558; rebuilt as GP9R #4613 in 1990. |

| GP9 | 4559 | GR-17j | 22835 | 3/1957 | ex-GTW #4559 |

| GP9 | 4902 | GR-17e | 21458 | 6/1956 | ex-GTW #4902; rebuilt as GP9R #4633 in 1992. |

| GP9 | 4903 | GR-17e | 21459 | 6/1956 | ex-GTW #4903; rebuilt as GP9R #4629 in 1992. |

| GP9 | 4904 | GR-17e | 21460 | 6/1956 | ex-GTW #4904; rebuilt as GP9R #4610 in 1992. |

| GP9 | 4905 | GR-17e | 21461 | 6/1956 | ex-GTW #4905; rebuilt as GP9R #4616 in 1992. |

| GP9 | 4906 | GR-17e | 21462 | 6/1956 | ex-GTW #4906; rebuilt as GP9R #4627 in 1992. |

| GP9 | 4923 | GR-17k | 22829 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GPR9 #4612 in 1990. |

| GP9 | 4924 | GR-17k | 22830 | 3/1957 | Adorned in a special US Coast Guard livery from 1979-1980. Rebuilt as GPR9 #4617 in 1990. |

| GP9 | 4925 | GR-17k | 22831 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GPR9 #4609 in 1990. |

| GP9 | 4926 | GR-17k | 22832 | 3/1957 | - |

| GP9 | 4927 | GR-17k | 22833 | 3/1957 | Rebuilt as GPR9 #4618 in 1991. |

| GP9 | 4928 | GR-17s | 23995 | 12/1957 | Rebuilt as GPR9 #4620 in 1991. |

| GP9 | 4929 (1st) | GR-17s | 23996 | 12/1957 | Wrecked in October, 1972 in head-on collision with a Boston & Maine SW1 at Belcherton, Massachusetts. |

| GP9 | 4929 (2nd) | GR-17s | 20316 | 6/1955 | ex-Northern Pacific #229/Burlington Northern #1855. Acquired in December, 1973. |

| GP38AC | 5800-5811 | - | 37929-37940 | 12/1971 | ex-GTW #5800-5811 |

Steam Roster (Post 1900)

| Wheel Arrangement | Class | Road Number(s) | Quantity | Builder | Completion Date | Retirement/Scrapped | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6-0 | O-9-aa | 387-389 | 3 | Lima | 1912 | 1952-1954 | - |

| 0-8-0 | P-1-a | 500-507 | 8 | Alco-Schenectady | 1923 | 1956-1959 | Four examples transferred to CN in 1942. |

| 2-8-0 | M-2-a | 400-408 | 9 | Alco-Schenectady | 1905 | 1944-1954 | Four examples transferred to CN in 1928. |

| 2-8-0 | N-4-h | 409-418 | 10 | Alco-Schenectady | 1906 | 1957-1961 | Transferred to CN in 1928. |

| 2-8-0 | M-3-a | 450-455 | 6 | Alco-Schenectady | 1916 | 1955-1960 | Renumbered from 420-425. |

| 2-8-0 | N-5-a | 460-475 | 16 | Alco-Schenectady | 1923 | 1955-1960 | - |

| 2-10-4 | T-3-a | 700-709 | 10 | Alco-Schenectady | 1928 | 1954-1959 | - |

| 4-6-0 | I-6 | 211-217 (not sequential) | 3 | Alco-Schenectady | 1904, 1906 | 1928-1941 | - |

| 4-6-0 | I-7-a | 218-221 | 4 | Alco-Schenectady | 1915-1916 | 1943-1955 | - |

| 4-6-2 | K-3-b | 230-232 | 3 | Baldwin | 1912 | 1952-1954 | - |

| 4-8-2 | U-1-a | 600-603 | 4 | Alco-Schenectady | 1927 | 1956-1959 | - |

Central Vermont 4-8-2 #601 (U-1-a) is seen here being serviced in White River Junction, Vermont on October 31, 1953. Author's collection.

Central Vermont 4-8-2 #601 (U-1-a) is seen here being serviced in White River Junction, Vermont on October 31, 1953. Author's collection.Today

During the 1950s, diesels from CN began to appear on CV rails and all steam serviced ended after 1957. The 1960s were an especially rough period due to declining traffic, rising costs, and falling revenues.

Its one-time rival, the Rutland, fared no better and shutdown entirely after September of 1960 following a severe strike.

During the 1970s, a restructuring of the CN's corporate affairs placed the Central Vermont under the Grand Trunk Corporation. From this point forward it mostly operated as a paper company with "CV" lettering, in script identical to its parent featured on equipment.

In early 1995 the Central Vermont disappeared when Canadian National sold the property to short line conglomerate RailTex, renaming it as the New England Central Railroad.

In 2000, RailTex was acquired by RailAmerica, which in turn was purchased by Genesee & Wyoming in 2012. Today, NECR operates a system of nearly 400 miles maintaining the entirety of the original CV network, now also owning the ex-B&M trackage.

Recent Articles

-

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail.