Front Range Passenger Rail [Fort Collins-Pueblo, CO]

Published: January 25, 2026

By: Adam Burns

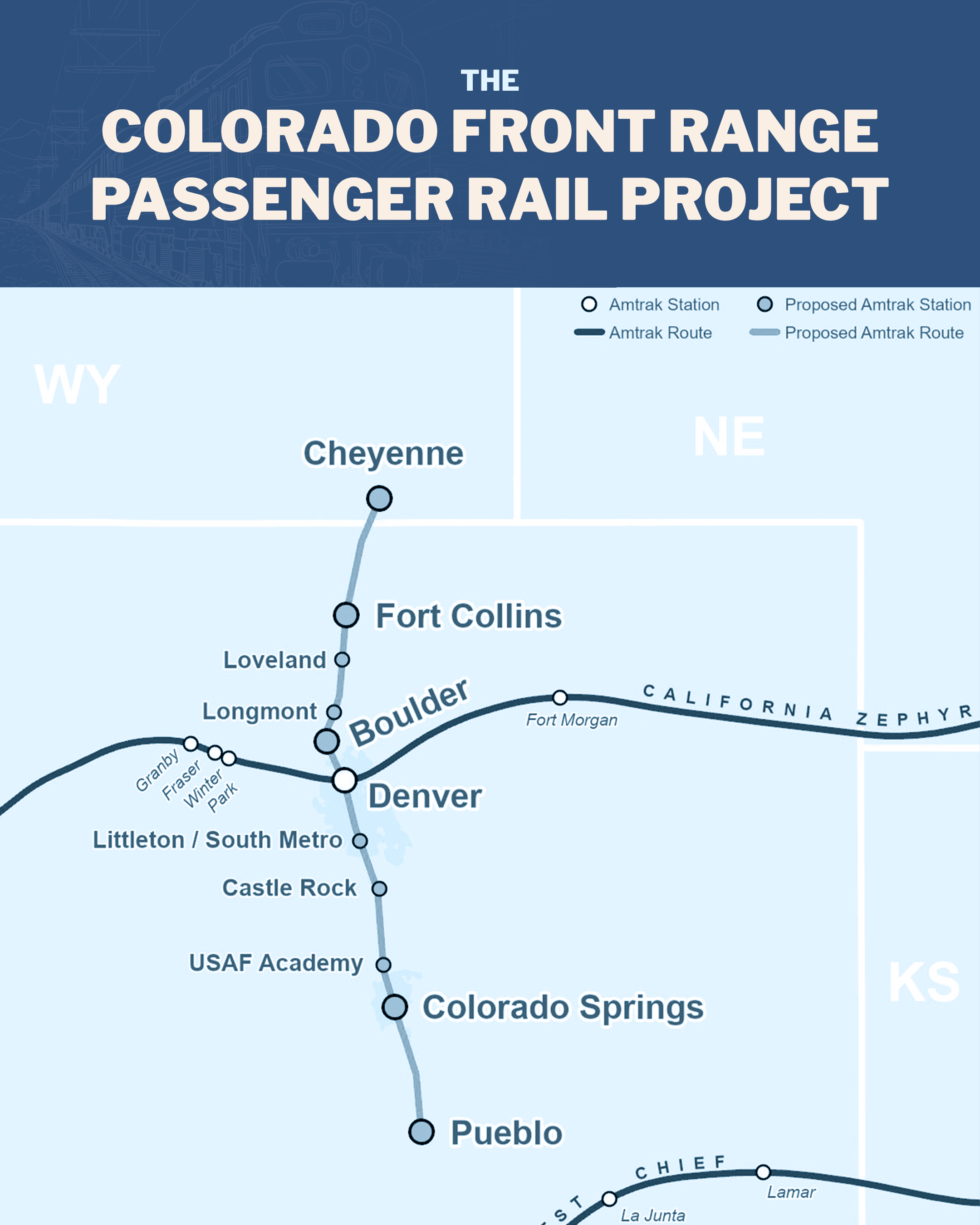

For decades, Coloradans have debated an idea that seems both obvious and daunting: a passenger train that runs along the Front Range, linking the state’s biggest population centers along Interstate 25—Fort Collins, Denver, Colorado Springs, and Pueblo—while also stitching in smaller communities in between. Today, that concept has a formal name, a governing agency, and a planning pipeline: the Front Range Passenger Rail (FRPR) project.

If you’ve ever crawled through weekend I-25 traffic, watched weather snarl the Monument Hill corridor, or tried to time a flight connection out of Denver without padding your schedule by an hour “just in case,” you already understand the appeal. FRPR is being positioned as a new, reliable intercity travel option—one that uses existing rail corridors, connects to local transit, and (ideally) scales up over time into a truly regional rail backbone.

The big story, though, is that FRPR has moved beyond a fuzzy vision statement. Colorado created a dedicated rail district to plan, finance, build, and eventually operate the service, and it’s now deep in the long process that turns a “wouldn’t this be nice?” into trains on the timetable.

A pair of Amtrak SDP40Fs have the westbound "San Francisco Zephy" near Denver on March 10, 1977. Gary Morris photo.

A pair of Amtrak SDP40Fs have the westbound "San Francisco Zephy" near Denver on March 10, 1977. Gary Morris photo.The Big Picture: What FRPR Is Trying to Do

At its core, Front Range Passenger Rail is envisioned as the transportation “spine” along the Front Range, integrating with other east-west and local multimodal systems. Colorado’s transportation leadership has framed the corridor as a logical response to growth and congestion, particularly in the roughly 173-mile stretch from Pueblo to Fort Collins via Denver that contains a large share of the state’s population.

The FRPR District’s public-facing description is straightforward:

- Where: Initially, service is envisioned from Fort Collins through Denver and south to Pueblo, with a long-term vision that could eventually connect north and south beyond Colorado’s borders.

- How: The plan is to use existing tracks shared with freight railroads and leverage new federal passenger-rail programs created under recent federal infrastructure legislation.

- When: The District says it is evaluating routes, stations, infrastructure, operations, costs, and financing, with the first train potentially operating “within the decade,” depending on funding, agreements, and project development.

That “within the decade” line is the optimistic headline—but the more meaningful detail is the machinery now in motion: governance, corridor planning, station planning, service modeling, environmental review, and ultimately a decision about how to pay for it.

From Study to Structure: How the Project Evolved

Colorado’s Front Range rail push didn’t begin with the District. In 2017, an existing state commission focused on the Southwest Chief was repurposed into the Southwest Chief & Front Range Passenger Rail Commission, which then became a key state-level forum for advancing the Front Range corridor vision. By 2018, the Colorado General Assembly directed funding toward development of a rail passenger service plan for the corridor.

The biggest modern milestone came in 2021, when Colorado passed legislation creating the Front Range Passenger Rail District—a government agency specifically empowered to plan, finance, construct, operate, and maintain an interconnected passenger rail system along the Front Range. The enabling bill also required coordination with RTD for system connectivity and with Amtrak for connections to services like the Southwest Chief, California Zephyr, and Winter Park Express.

In other words: FRPR isn’t just a study anymore. It’s a public entity with a mission and a mandate.

The Corridor: Likely Endpoints and “In-Between” Communities

The most commonly discussed backbone route is Fort Collins → Denver → Colorado Springs → Pueblo, roughly paralleling I-25. The District describes this as the initial service concept.

While final station locations are part of ongoing planning, it’s helpful to think of FRPR in two layers:

1) Primary city anchors

These are the big trip generators that make the corridor pencil out:

2) Intermediate Front Range markets

- Fort Collins area

- Denver metro (with a natural focal point at Denver Union Station and its transit connections)

- Colorado Springs area

- Pueblo area

Most versions of the concept include a set of intermediate stops—communities that are large enough to matter, close enough to generate short trips, and positioned to connect with local transit or park-and-ride access.

A 2024 regional planning update noted that the District was working toward pinning down nine primary stations by Spring 2026 and had finalized station location criteria while coordinating with local jurisdictions.

That sort of language matters, because it hints at what FRPR is really becoming: not just a “train between four cities,” but a corridor service with multiple stations designed to build ridership and provide useful trip options for commuters, students, events, and airport connections.

What the Service Might Look Like

Unlike true high-speed rail proposals, FRPR is being framed as intercity passenger rail on existing corridors, meaning the service is likely to resemble higher-quality regional rail: multiple round trips per day, useful schedules, comfortable equipment, and reliable end-to-end travel times—so long as the host-railroad agreements and infrastructure improvements support it.

A 2025 FRPR District overview presentation points to typical intercity passenger rail speeds, including 79 mph operation and a Fort Collins–to–Pueblo travel time estimate of just over three hours (as a planning-level figure).

That is significant. A three-hour rail trip across the whole Front Range could compete well with driving when highway conditions are bad—and it becomes especially attractive when you factor in avoiding parking, weather stress, and the “I-25 roulette” that locals know too well.

But shared-track service also comes with unavoidable complexity:

- Freight railroads own or control much of the infrastructure.

- Passenger service often requires capacity projects (sidings, signals, track upgrades), dispatching agreements, and performance standards.

- Service reliability depends on how those agreements are structured and enforced.

In the District’s own planning updates, “operations and service modeling with host railroads” is a major workstream, with broader service development planning targeted for completion in the mid-2020s timeframe.

Governance

One reason FRPR has more momentum than many past proposals is that Colorado created a district whose sole job is to push the project forward. The District describes itself as a government agency tasked with designing, financing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the system.

A 2024 regional update presentation also summarized the organization’s structure and partnerships—highlighting collaboration with agencies like CDOT, RTD, and the FRA, as well as the District’s internal staffing and budgeting needs as it matures.

For rail projects, this is more than bureaucratic trivia. Governance determines:

- who negotiates with the freight railroads,

- who applies for federal grants,

- who sets service priorities,

- and who is accountable when hard tradeoffs appear (cost, stations, frequency, fares, and timing).

Planning Pipeline

A major accelerant for passenger rail nationally has been the Federal Railroad Administration’s Corridor Identification and Development (Corridor ID) Program—a structured pipeline intended to help move corridors from early feasibility to readiness for implementation funding. In its FY2024 report to Congress, the FRA described Corridor ID as a long-term development pathway designed to guide intercity passenger rail projects and prepare them for future capital programs.

In Colorado’s case, a regional planning update noted the FRPR effort was accepted into the Corridor ID Program in December 2023, which positioned it to pursue federal support for service planning and environmental clearance (with typical federal/local match structures discussed in planning materials).

This matters because Corridor ID participation can help:

- formalize scope and phasing,

- provide technical assistance,

- strengthen grant competitiveness,

- and impose a stepwise structure that keeps a project moving.

The same update presentation laid out key work items: route and station market analyses, service and operations modeling, defining capital and operating costs, and assembling a financial and implementation plan.

Funding

Every passenger rail proposal eventually arrives at the same fork in the track: how do you pay for it—not just to build it, but to operate it year after year?

Colorado has explored multiple funding angles, and the conversation has included both state-level revenue tools and a future voter-approved tax within the District’s territory.State funding tools and “match money”

A widely discussed strategy is using state-generated revenue as “match” to unlock larger federal grants. One 2024 report in The Colorado Sun described how a rental-car fee increase was expected to generate tens of millions annually, specifically to help Colorado compete for federal passenger-rail grants.

A CTIO/fee forecast document projected substantial revenue from a congestion impact fee on short-term vehicle rentals (with projections rising into the tens of millions annually in the mid-2020s). The ballot measure timeline

Public reporting in 2024 indicated that rail leaders were leaning toward waiting until 2026 to ask voters for a sales tax, citing the need for more planning and outreach before putting a major tax question on the ballot. Colorado Public Radio reported that the District’s executive committee argued for more time despite political pressure to move faster.

In short: the project can’t live on planning money forever. If Colorado wants frequent, reliable Front Range trains, it will likely require a durable funding source—one that voters are willing to support once the plan is concrete enough to defend.

Benefits

FRPR’s advocates and official materials generally emphasize four themes:

- Reliable travel in a corridor where growth and congestion are expected to worsen, and where highway trips can be unpredictable.

- Connected communities, linking major job centers, education hubs, events, and local transit systems.

- Economic development, including station-area investment and easier access to regional labor markets.

- Sustainability and air quality, especially relevant along the Front Range where vehicle emissions and congestion are perennial concerns.

Even the planning-level “just over three hours” corridor runtime estimate hints at the real prize: a service that is useful, not symbolic—one that makes day trips, meetings, and connections feasible without the stress of driving.

Challenges

If you want to understand whether FRPR will succeed, watch these pressure points:

Freight railroad agreements

Shared-track passenger service rises or falls on negotiated performance and capacity. Typically, freight railroads are notoriously against allowing any type of passenger or commuter rail operations share their corridors as it provides no direct benefits to these private companies and only slows freight operations. This is where timelines often slip and costs often climb.

Station choices and local politics

Stations create winners and losers—downtown vs. edge-of-town, park-and-ride vs. walk-up urban access, which communities get “primary” status, and which get phased later.

The operating subsidy question

Even with strong ridership, most U.S. intercity corridors require some form of public operating support. That reality has to be explained clearly if the project goes to voters.

Delivering early wins

Projects often need “independent utility” segments—something that can open earlier (even a limited starter line) to build public confidence. Regional planning discussions have referenced prioritizing near-term rail service segments as part of broader coordination.

What Comes Next

As of the most recent planning materials available publicly, the District is working through the heavy-lift phase: service development planning, station planning coordination, host railroad negotiations, environmental processes, and a financial plan—while also building the coalition that would be needed for a successful ballot measure.

If FRPR reaches the point where voters are asked to fund it, the debate will likely hinge on a simple question: Is this a real, phased, buildable plan—or just another study? The good news for supporters is that Colorado now has the institutional structure and federal planning pathways to turn the concept into something tangible. The hard part is still ahead: locking in agreements, assembling capital funding, and convincing a fast-growing region that the long game is worth it.

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 01:34 PM

The Wisconsin Great Northern Railroad will once again welcome passengers aboard its popular Spring BBQ Dinner Train in 2026. -

Connecticut DOT Awards $20 Million In Railroad Grants

Mar 12, 26 01:19 PM

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) has announced a new round of funding aimed at improving the safety, reliability, and capacity of the state’s freight rail network. -

California's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 12:59 PM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Reading & Northern Unveils Semiquincentennial 1776

Mar 12, 26 12:48 PM

In November 2025, the Reading, Blue Mountain & Northern Railroad (RBMN)—commonly known as the Reading & Northern—announced the debut of a striking patriotic locomotive commemorating the upcoming 250th… -

New Jersey's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:35 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Florida BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:28 AM

While Florida does not currently offer any BBQ train rides the Florida Railroad Museum does host a similar event, a campfire experience! -

Texas "Murder Mystery" Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:40 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:36 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

Missouri's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:33 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:28 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Charlotte Approves $37.9M For "Red Line" To Lake Norman

Mar 11, 26 02:18 PM

The Charlotte City Council has approved $37.9 million in funding for the next phase of design work on the long-planned Red Line commuter rail project. -

NS, Progress Rail Announce SD70ICC Modernization

Mar 11, 26 12:15 PM

Norfolk Southern Railway has announced a significant locomotive modernization initiative in partnership with Progress Rail Services Corporation that will rebuild 96 existing road locomotives into a ne… -

Colorado Seeks Input On Proposed Front Range Passenger Train Name

Mar 11, 26 11:55 AM

Colorado officials are inviting the public to help name a proposed passenger train that could one day connect major cities along the state’s heavily traveled Interstate 25 corridor. -

Virginia Whiskey Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 11:22 AM

Among the Virginia Scenic Railway's most popular specialty excursions is the “Bourbon & BBQ” tasting train, an adults-oriented rail journey that pairs scenic views of the Shenandoah Valley with guided… -

Minnesota's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:32 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train. -

New Mexico's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:23 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Indiana's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:19 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:02 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Kentucky Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 11:39 AM

The Bluegrass State is home to beautiful rolling farms and the western Appalachian Mountain chain, which comes alive each spring. A few railroad museums host Easter-themed events during this time. -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:26 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

NS Faces Multiple Derailments Near Historic Horseshoe Curve

Mar 10, 26 10:15 AM

One of America’s most famous railroad landmarks, the legendary Horseshoe Curve west of Altoona, Pennsylvania, has recently been the site of multiple freight-train derailments involving Norfolk Souther… -

Oregon's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:11 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:57 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Connecticut's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:54 AM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on… -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:37 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Union Pacific Restores Rail Bridge Service in Lincoln

Mar 09, 26 11:34 PM

Union Pacific crews have successfully restored freight rail service across a key bridge in Lincoln, Nebraska, completing a rapid reconstruction effort in just a few weeks. -

TVRM To Assist In Gas-Powered Locomotive's Restoration

Mar 09, 26 11:15 PM

The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum has announced it is assisting in the eventual cosmetic restoration of a former gas powered locomotive used in the logging industry. -

Michigan's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:37 AM

Spring sometimes comes late to Michigan but this doesn't stop a handful of the state's heritage railroads from hosting Easter-themed rides. -

Pennsylvania's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:05 AM

Pennsylvania is home to many tourist trains and several host Easter-themed train rides. Learn more about these special events here. -

Tennessee's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:33 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Michigan's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:07 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:56 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Maryland Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:37 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

New York's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:16 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:15 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Colorado Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:14 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:13 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 1356 Receives Cosmetic Restoration

Mar 07, 26 02:19 PM

A significant preservation effort is underway in Missoula, Montana, where volunteers and local preservationists have begun a cosmetic restoration of Northern Pacific Railway steam locomotive No. 1356. -

New York's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 02:08 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Kentucky's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:17 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Ohio's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:15 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

Georgia 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides In Cordele

Mar 07, 26 10:13 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel… -

Arizona Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:12 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Massachusetts's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 09:00 AM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:57 AM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

Indiana's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:55 AM

Among IRE’s most talked-about offerings is the Wine & Whiskey Train—an adults-only, evening-style trip that leans into the best parts of classic rail travel: atmosphere, comfort, and a little cele… -

North Carolina's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:53 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Arkansas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:50 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

California Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:49 AM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Construction Continues On Railroad Museum Of Pennsylvania Roundhouse

Mar 05, 26 01:52 PM

Construction is underway on a long-anticipated roundhouse exhibit building at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, a project designed to preserve several of the most historically signific…