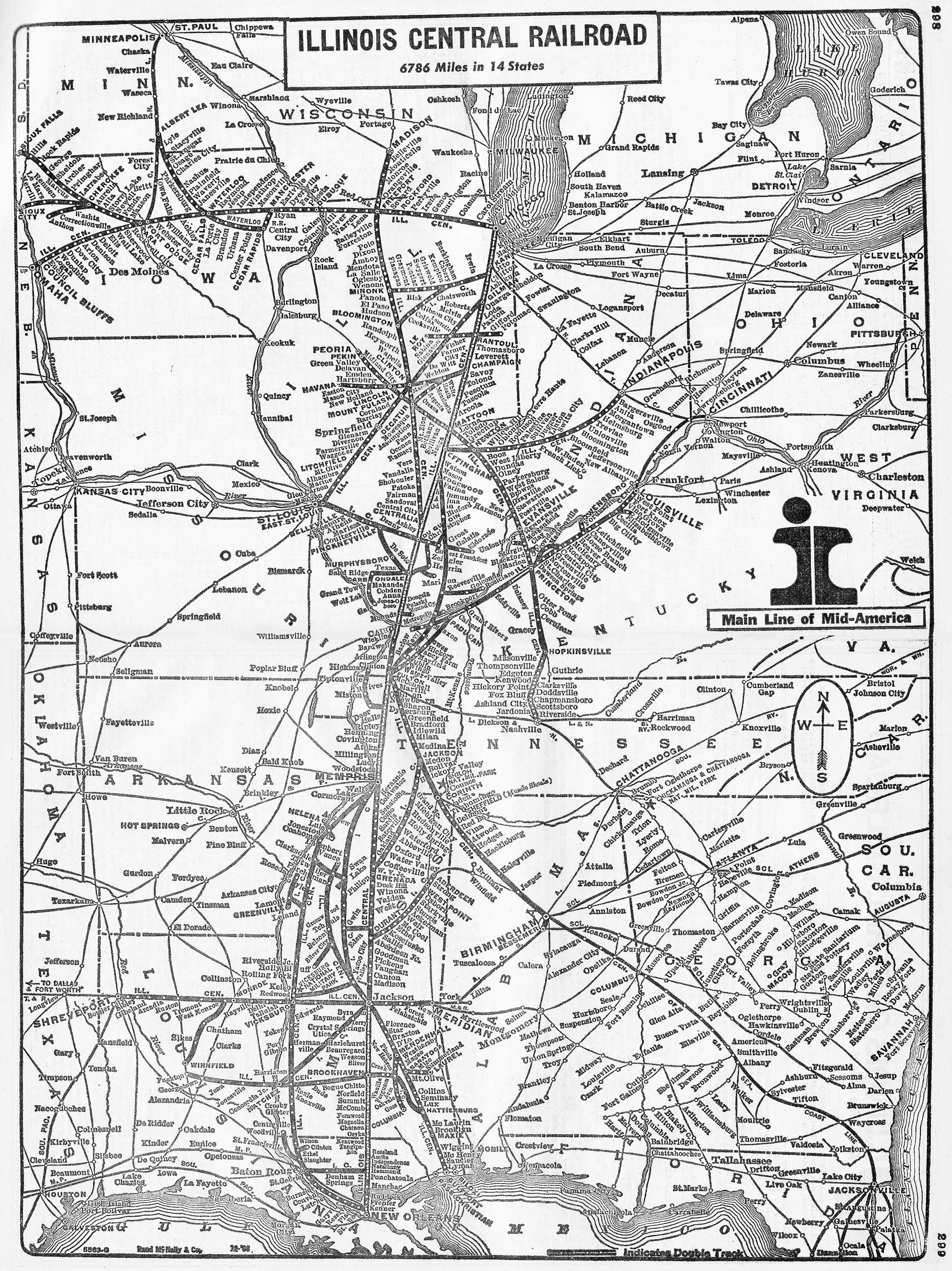

Illinois Central Railroad: Map, Logo, History

Last revised: October 16, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Illinois Central is a notable among notables. This storied company holds a special place of distinction alongside others like the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York Central, Milwaukee Road, Southern, Union Pacific, and Southern Pacific.

Its slogan, "The Main Line of Mid-America," perfectly described its unique north-south routing running from Chicago to the Gulf Coast. Only one other served the spine of America in such a way, the future Gulf, Mobile & Ohio (GM&O).

In a sense, IC was also a classic "granger" with its Iowa Division and multitude of branch lines scattered throughout Illinois, Kentucky, and the Deep South.

Due to its conservative nature it spent much of its corporate life as a profitable and well-managed operation, even avoiding bankruptcy during the Great Depression.

Perhaps a result of the desperate times it made a surprising move in merging with rival GM&O during the early 1970's. Considered an unsuccessful union, Illinois Central Gulf (ICG) spent more than a decade trying to reestablish profitability.

It finally regained its footing during the 1980's as a greatly slimmed-down railroad before its acquisition by Canadian National in 1998.

Photos

In this Illinois Central publicity photo new GP40's #3041 and #3042 pose with new boxcars in the late summer of 1967. Author's collection.

In this Illinois Central publicity photo new GP40's #3041 and #3042 pose with new boxcars in the late summer of 1967. Author's collection.History

Of the Illinois Central's many achievements perhaps the most remarkable was in retaining its original name while avoiding bankruptcy for its entire 148-year history.

Even if you know very little about railroads the name Illinois Central is likely familiar; its train, the "City of New Orleans," was immortalized when Steven Goodman released a song by the same name in 1971. It was made famous a year later through the lyrics or Arlo Guthrie. And then there is John Luther "Casey" Jones.

According to Mike Schafer's book, "Classic American Railroads," he selflessly scarified his life on April 30, 1900 to save those aboard the "New Orleans Special" (also known as the "Cannonball").

On that day, near Vaughan, Mississippi he successfully slowed his southbound train just enough to spare the lives of everyone involved (including all passengers and railroad personnel) before it crashed into a stopped southbound freight.

A friend of Jones and fellow company employee, engine wiper Wallace Saunders (an African American), is credited with the song which made him a legend, "The Ballad of Casey Jones."

Heritage

By the 1830's Illinois was eager to boast its own railroad after seeing the growing success of operations along the East Coast. Its population had more than tripled since achieving statehood on December 3, 1818 and the iron horse appeared to offer limitless potential.

In his book, "Illinois Central Railroad," author Tom Murray notes that after officials passed the Internal Improvement Act in 1837, $10 million was set aside to construct 1,300 miles across the state.

Illinois Central E8A #4028 is seen here tied down in Memphis, Tennessee on November 13, 1966. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Central E8A #4028 is seen here tied down in Memphis, Tennessee on November 13, 1966. American-Rails.com collection.Central Railroad

Notable to Illinois Central's future was a project to link Cairo, at the state's southern tip along the Ohio River to Galena near the Mississippi River (and not far from Dubuque, Iowa).

The route, unofficially referred to as the "Central Railroad," was estimated at $3.5 million. For years little occurred while another segment, an east to east alignment known as the Northern Cross Railroad, opened 55 miles in 1842 between the capital at Springfield and Meredosia.

As a result, according to the Trains Magazine's January, 2007 issue under a piece entitled, "Illinois: Crossroads Of American Railroads," the Northern Cross is recognized as the state's first placed into service (it later became part of the Wabash).

At A Glance

7,044 (1930) 6,539 (1952) 2,732 (1995) | |

Chicago - Mattoon, Illinois - Carbondale, Illinois - Grenada, Mississippi - New Orleans Memphis - Vicksburg, Mississippi - Baton Rouge, Louisiana - New Orleans Memphis - Greenwood, Mississippi - Jackson, Mississippi Fulton, Kentucky - Birmingham, Alabama Freeport, Illinois - Centralia, Illinois Chicago - Omaha Fort Dodge, Iowa - Sioux City, Iowa Cherokee, Iowa - Sioux Falls, South Dakota Manchester - Cedar Rapids, Iowa Waterloo, Iowa - Albert Lea, Minnesota Centralia, Illinois - Madison, Wisconsin Gilman, Illinois - St. Louis St. Louis - Du Quoin, Illinois Edgewood, Illinois - Fulton, Kentucky Fulton - Paducah - Louisville Effingham, Illinois - Indianapolis, Indiana Mattoon - Decatur - Peoria, Illinois Jackson - Gulfport, Mississippi Meridian, Mississippi - Shreveport, Louisiana | |

Freight Cars: 49,226 Passenger Cars: 857 | |

With the Central Railroad languishing in uncertainty it became clear drastic action was needed. To get things moving a land grant bill was signed into law on September 20, 1850 which provided a staggering 2.5 million acres of federal lands.

The idea was relatively straight forward; this acreage would aid the railroad in its construction efforts by selling tracts for a profit. In return, the railroad would agree to complete the proposed route within six years and pay the state a small percentage of gross revenues.

According to John Stover's book, "History Of The Illinois Central Railroad," it was the first instance of federal lands assisting a railroad in its construction. The tactic would be used extensively in the coming years to help western lines complete their routes. The land grants proved the catalyst to reinvigorate interest.

Charter

On February 10, 1851 Governor Augustus French signed into law the charter for the Illinois Central Railroad. What became known as IC's "Charter Lines" included a pair of routes; the main line would head north from Cairo, pass through Clinton and reach Freeport before turning west and terminate at Dunleith (East Dubuque) along the Mississippi River. It would span a total of 453 miles.

In addition, a so-called branch would track due north from a point which later became Centralia (incorporated in 1859 it is named for the point where IC's Charter Lines converge) and reach Chicago, totaling 252 miles. A New England group, led by Robert Rantoul of Massachusetts, spearheaded the project.

A trio of Illinois Central GP9s, led by #9093 leads a northbound string of hoppers over the Toledo, Peoria & Western diamonds at Gilman, Illinois, circa 1963. Roger Puta photo.

A trio of Illinois Central GP9s, led by #9093 leads a northbound string of hoppers over the Toledo, Peoria & Western diamonds at Gilman, Illinois, circa 1963. Roger Puta photo.Groundbreaking

To get underway the group needed startup capital (construction was projected at $17 million while final costs ballooned to $26 million) and at first turned to European capitalists, most of whom were based in England. That angle proved unsuccessful but they caught a break when a few state-side investors were located.

Ultimately, overseas backers were found but the process of financing became a long-winded affair, which proved easier as the project advanced. Ironically, the railroad's groundbreaking took place on December 23, 1851 in Chicago.

Logo

Although this was on the proposed branch the city was the largest served and, as such, dictated priority. Building south, the first segment opened on May 21, 1852 to Calumet. The pace quickened from that point and the entire 705-mile railroad, forming a sort of "Y" was ready for service on September 27, 1856.

It was an unprecedented feat of engineering. While grades were relatively insignificant its size alone made the railroad impressive, there was none other like it around the world (Only the New York & Erie's [predecessor of the Erie Railroad] 447 miles between Lake Erie and the Hudson River came close to its length.).

System Map (1940)

The system had little trouble generating a profit as people flocked to the state, cultivating its land and turning Chicago into a vital metropolitan region which later became the railroad capital of America.

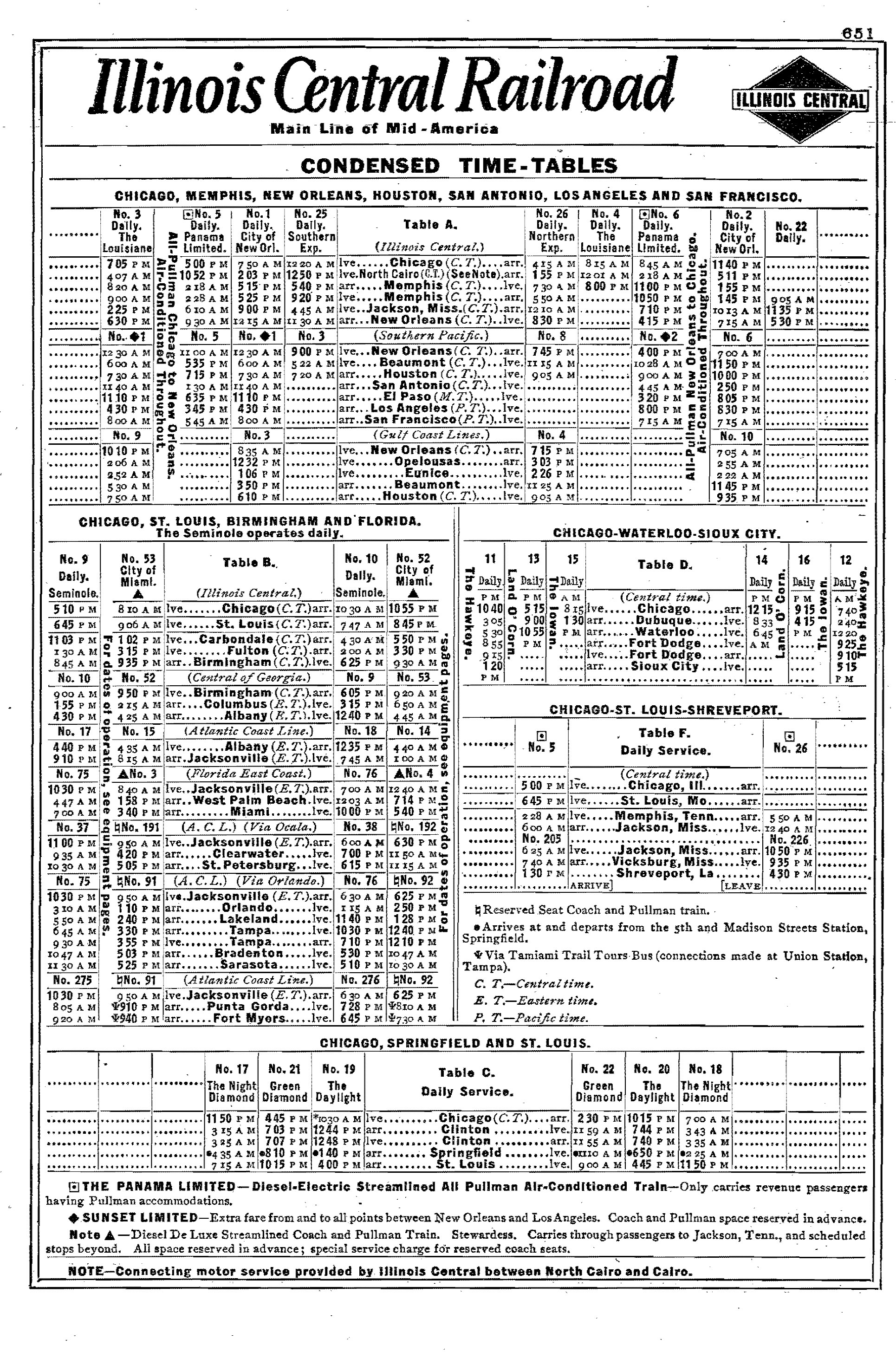

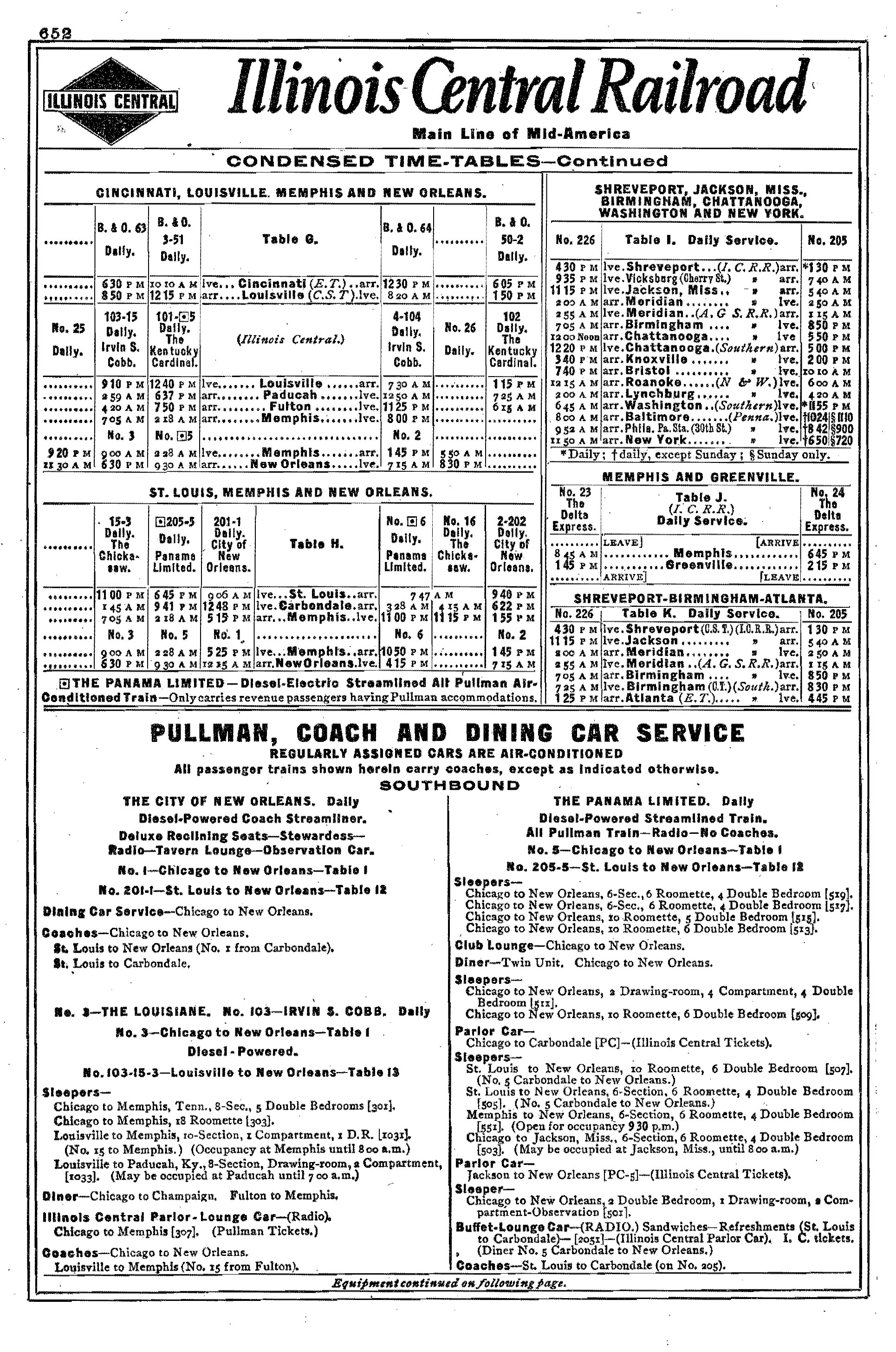

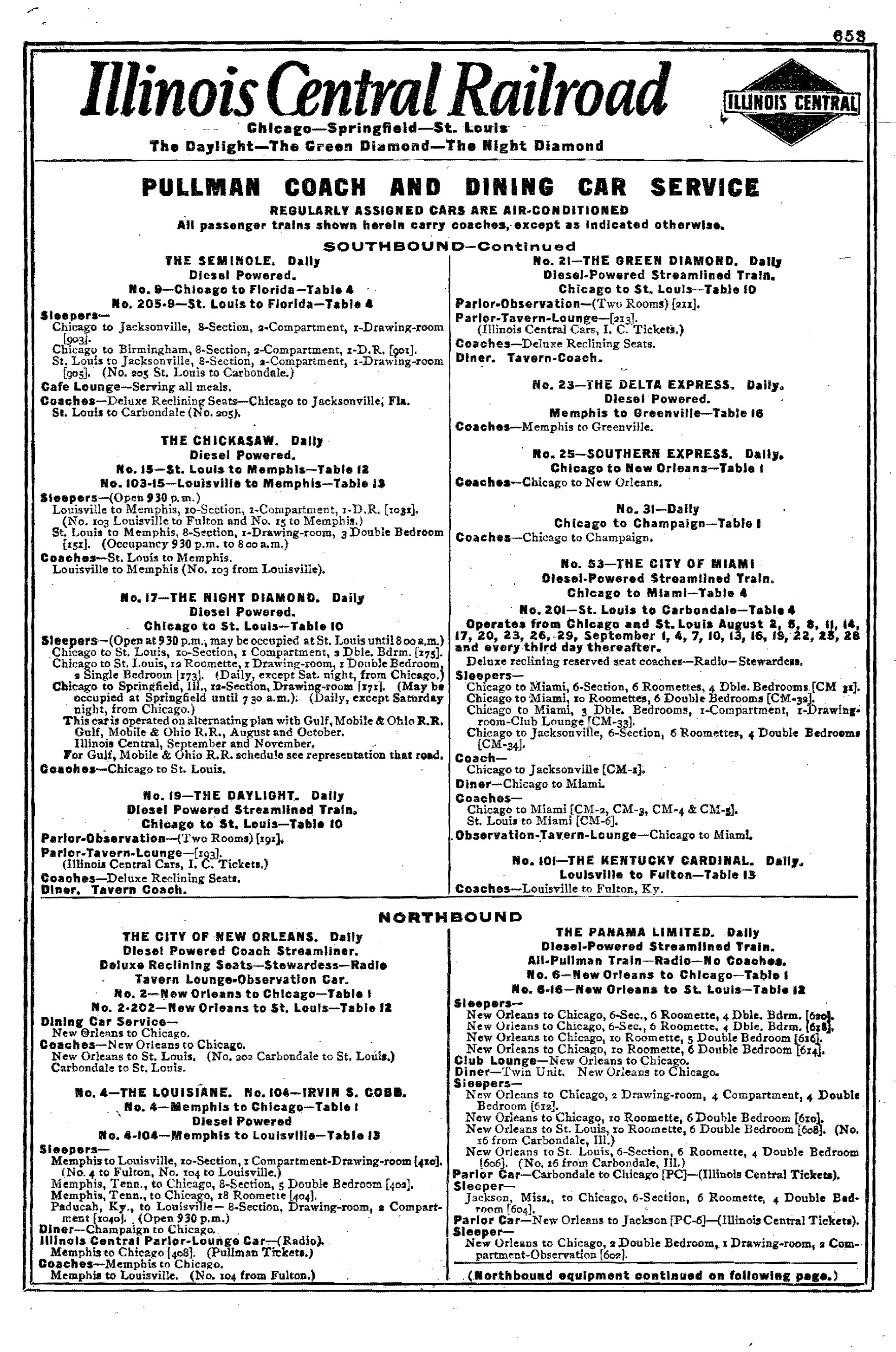

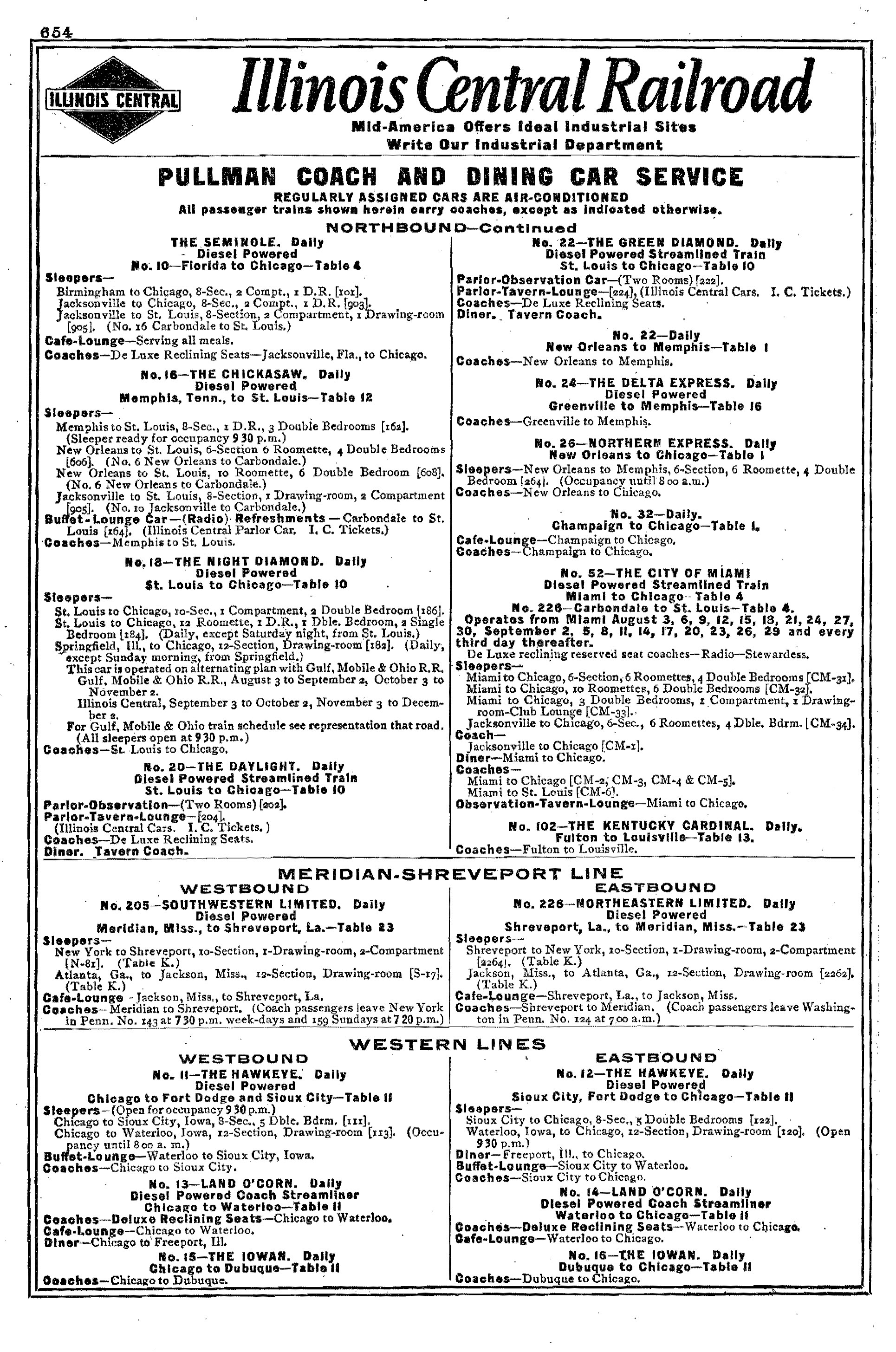

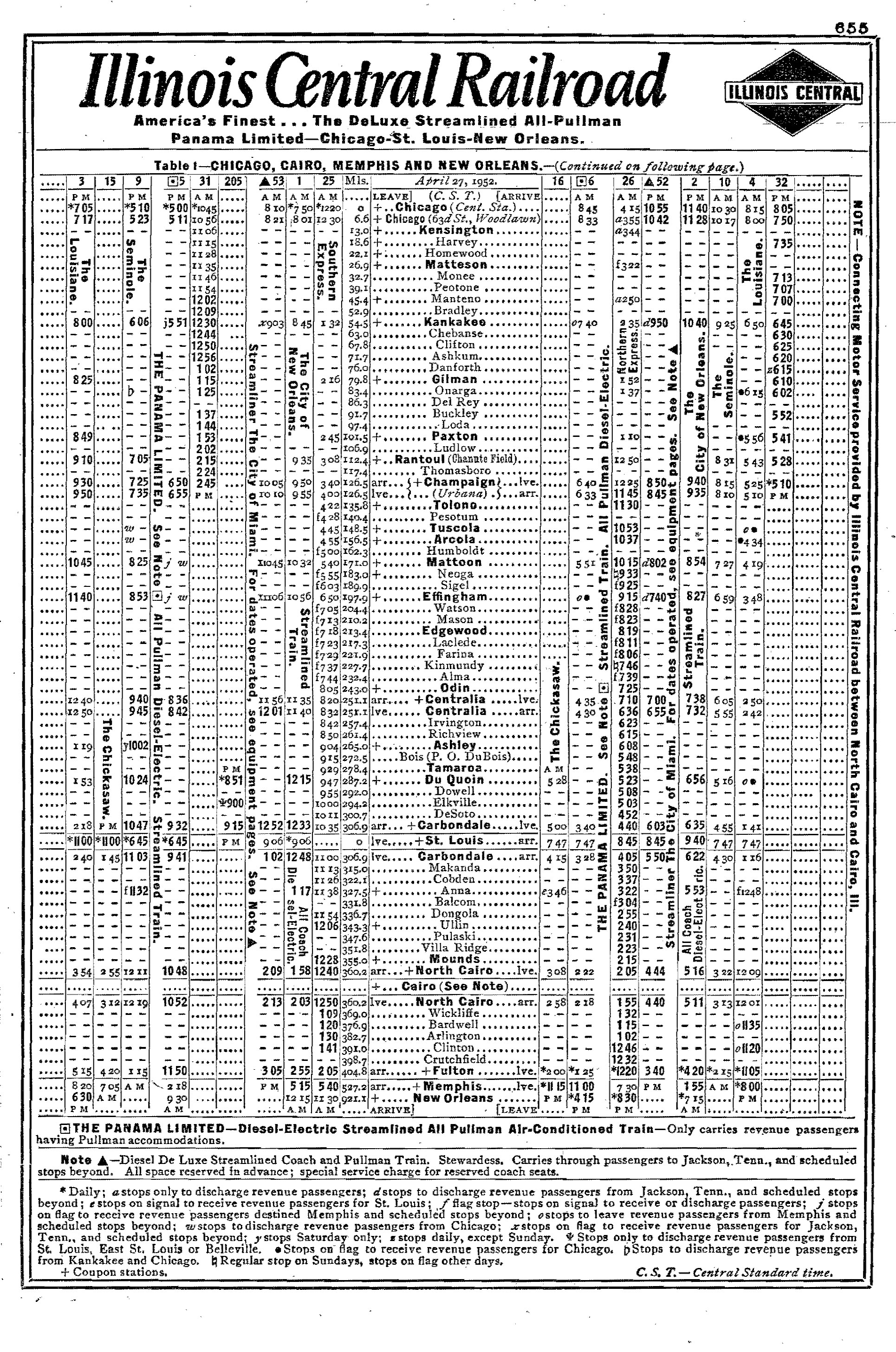

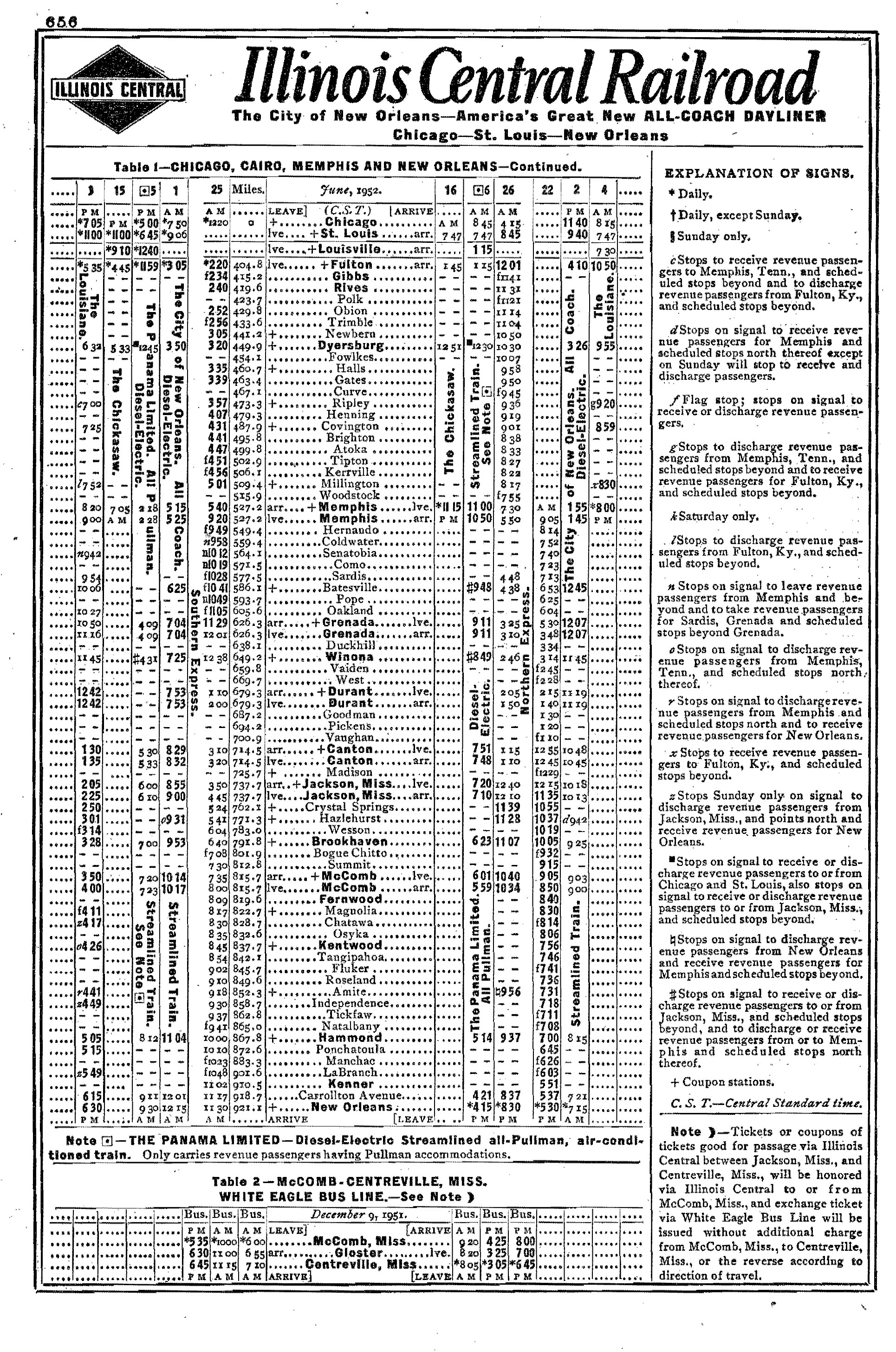

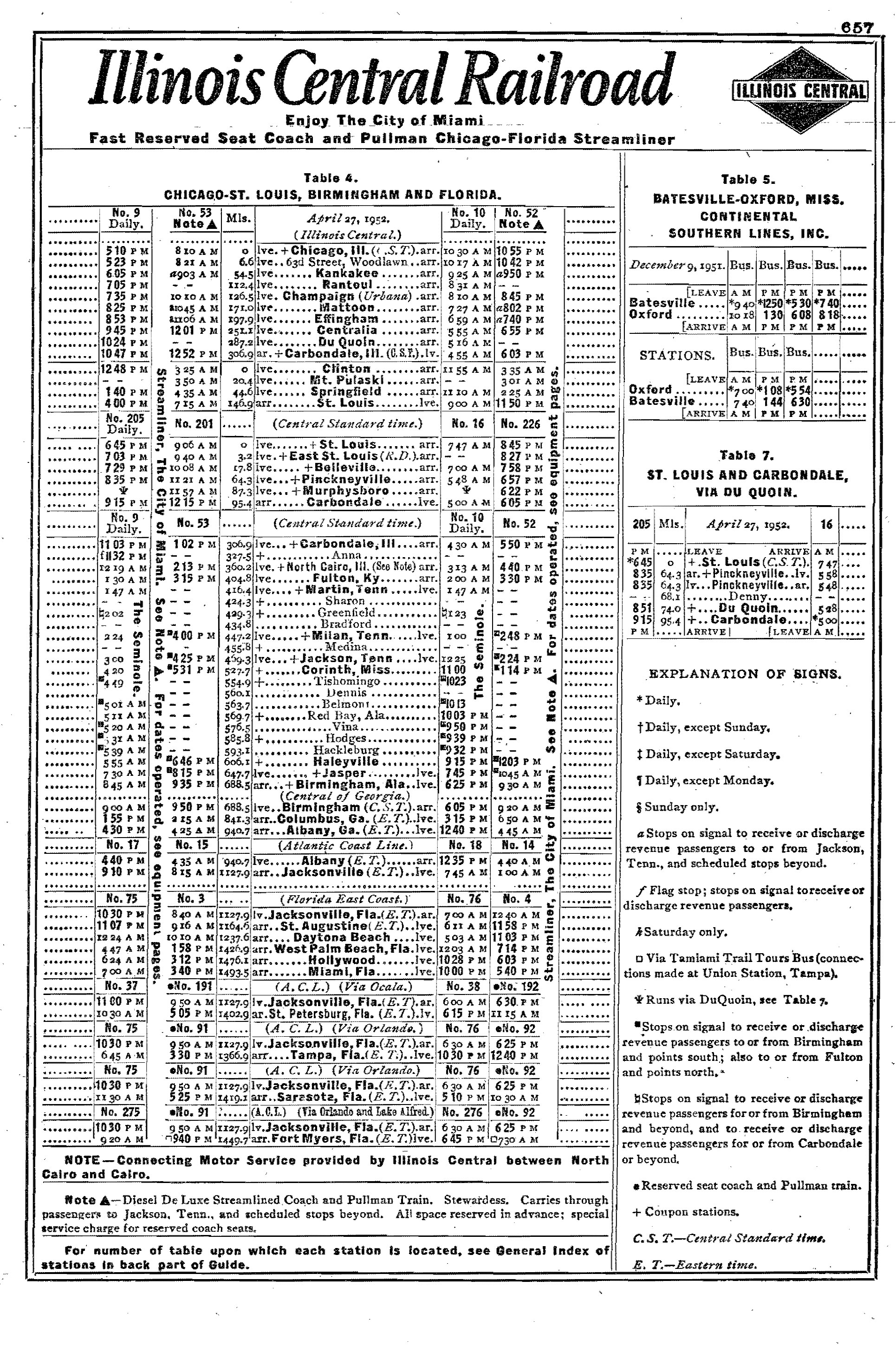

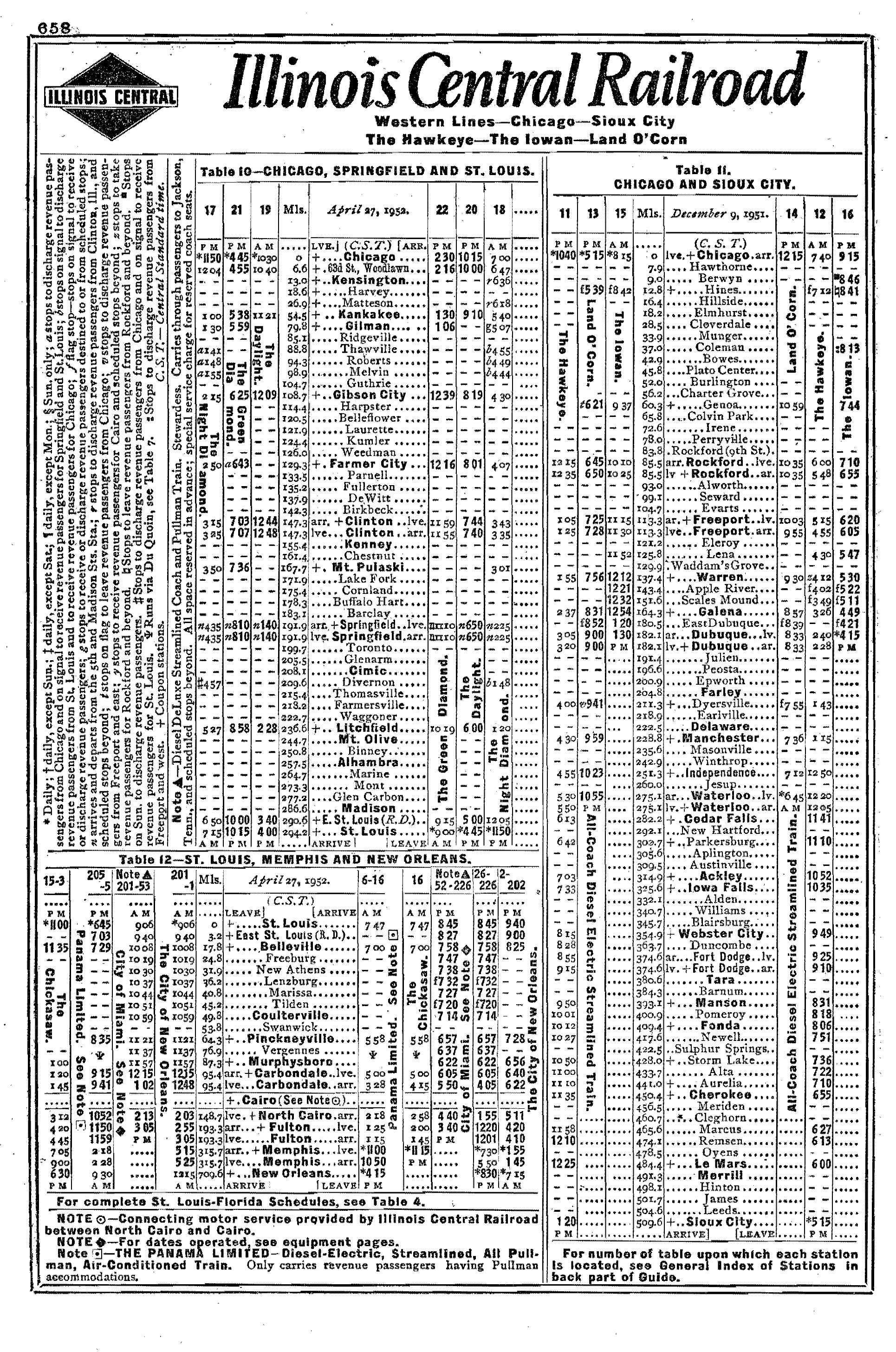

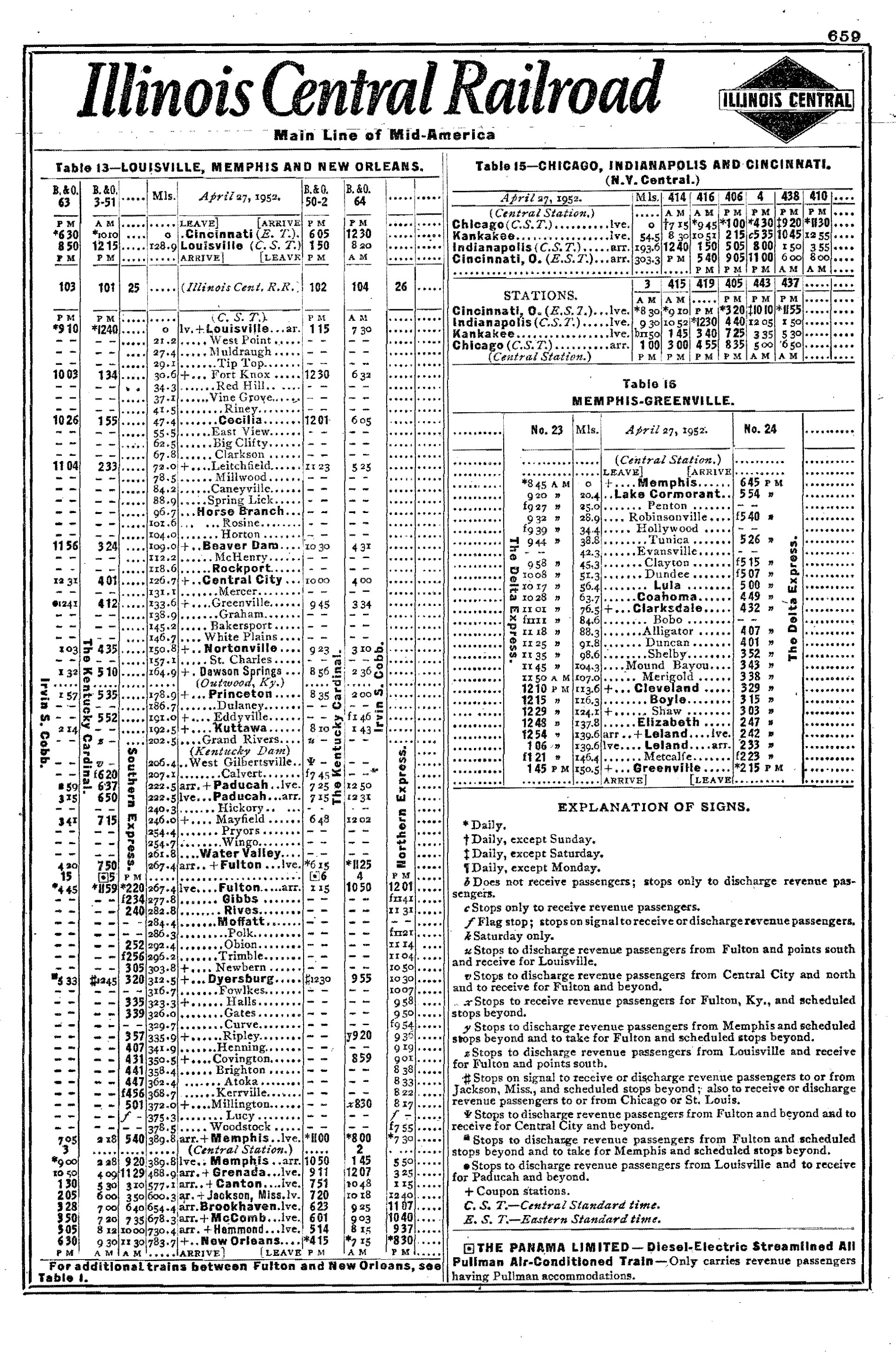

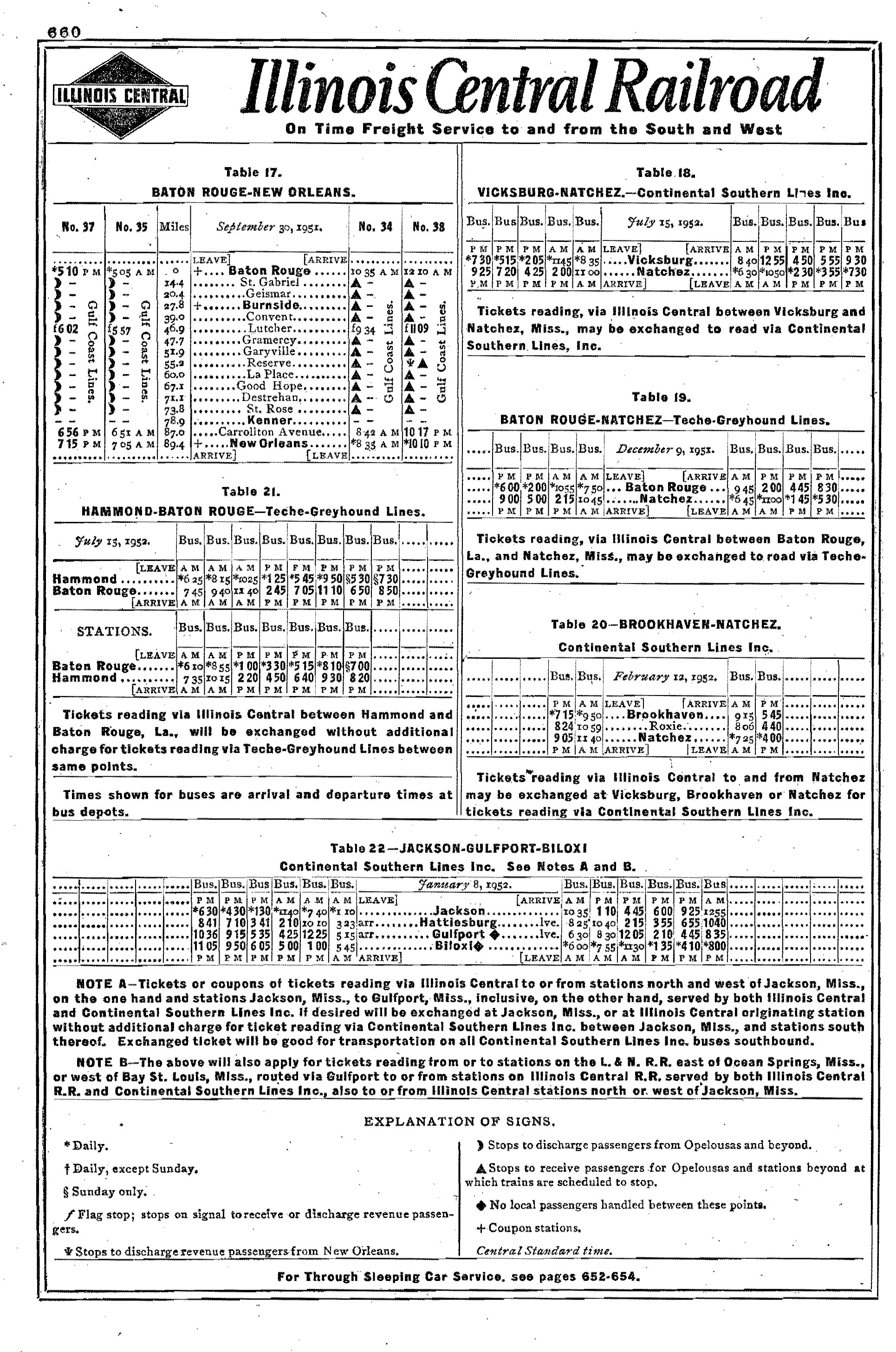

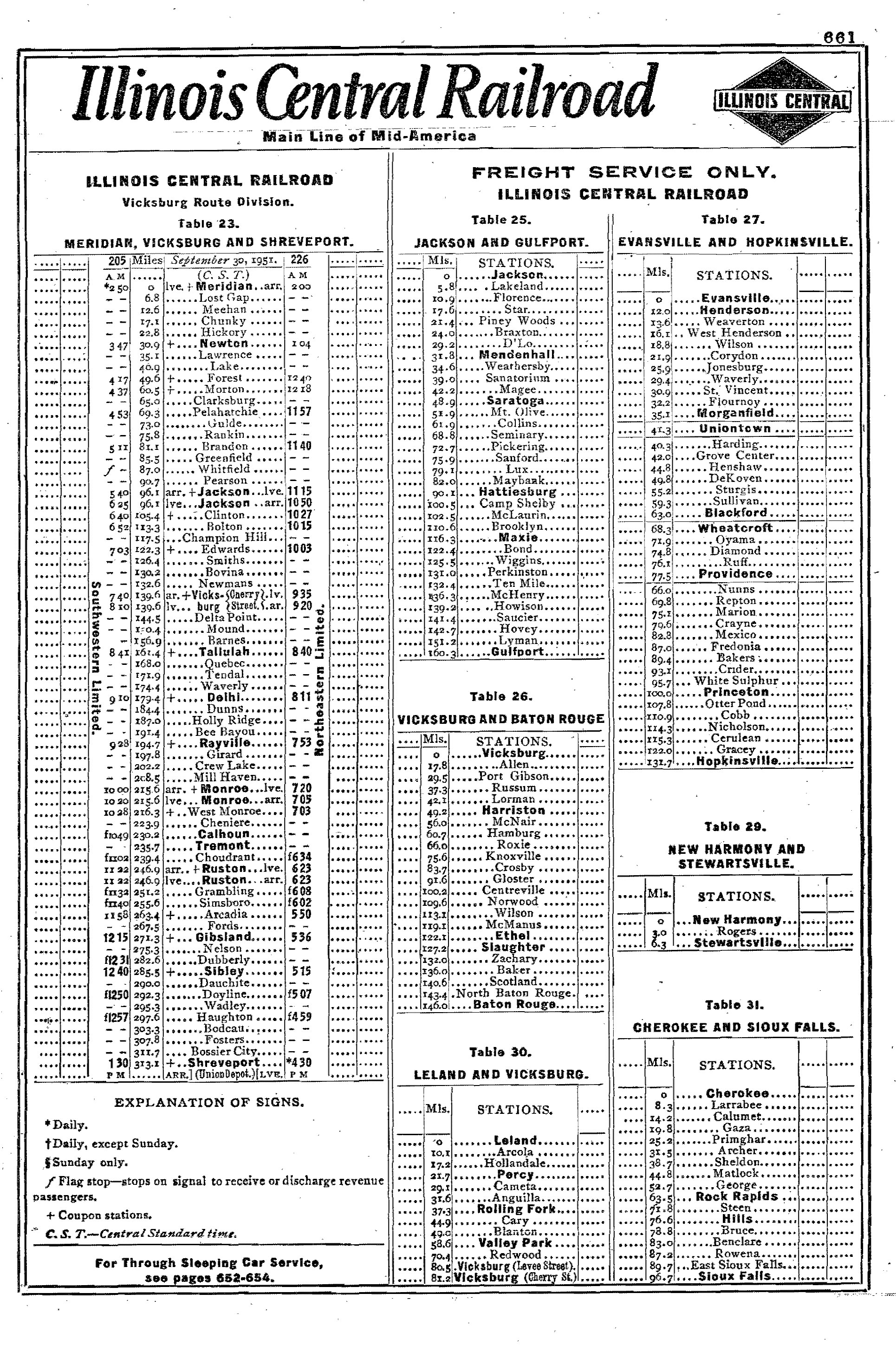

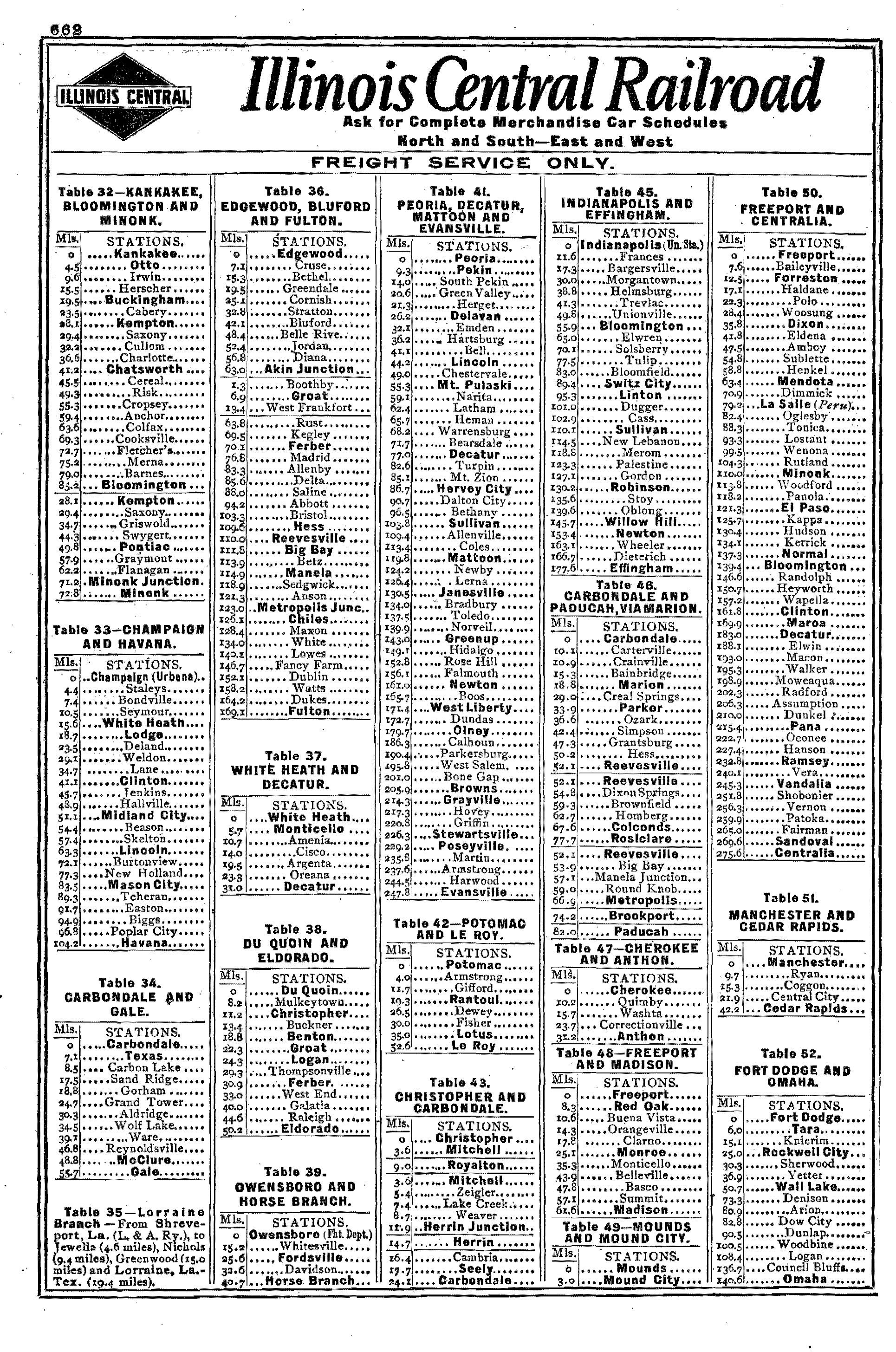

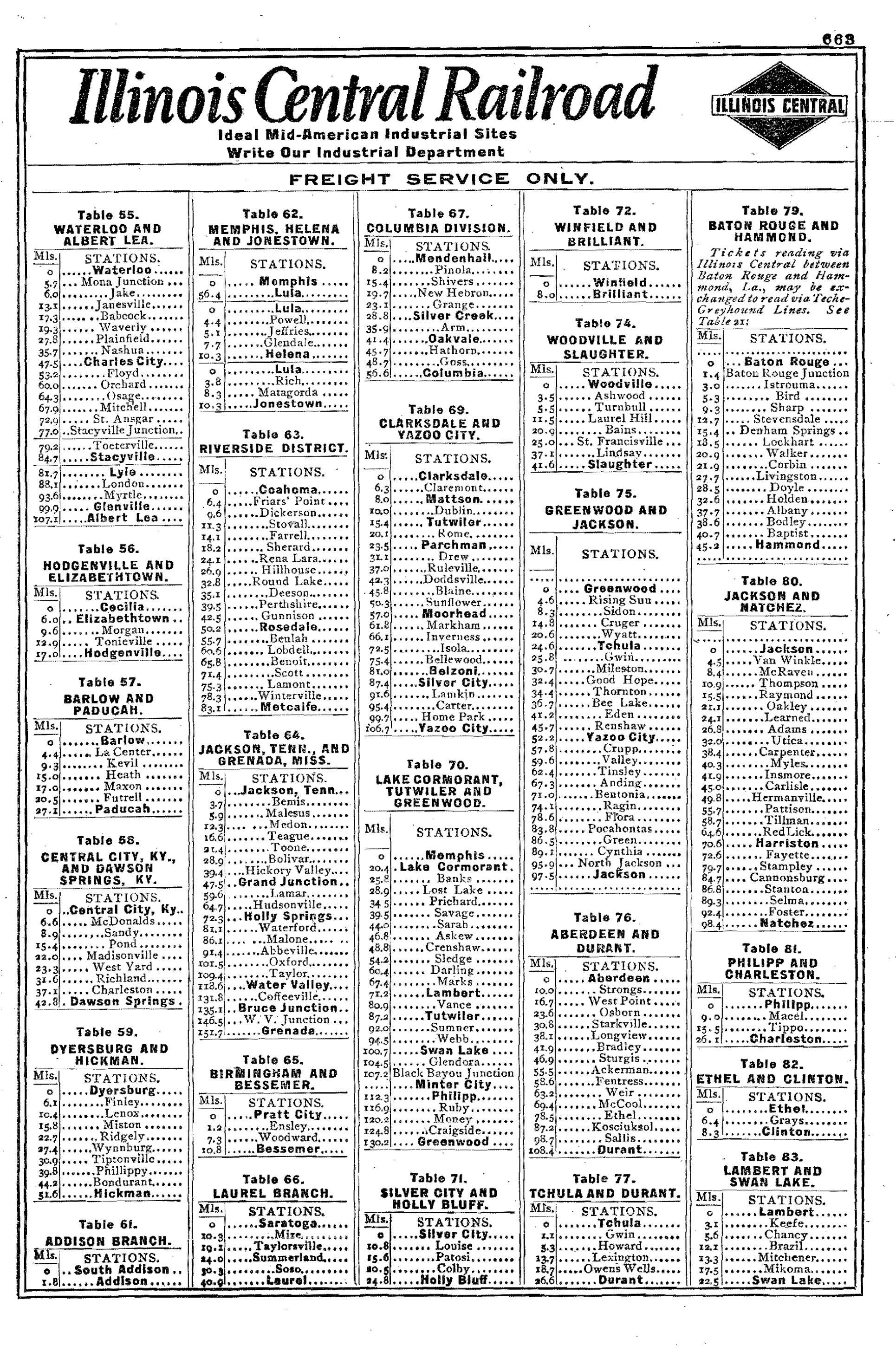

Timetable (1952)

While the IC handled every type of freight imaginable, even bananas from the Gulf Coast were once a lucrative venture, black diamonds remained important right from the start.

According to Donald Heimburger's book, "Illinois Central: Main Line Of Mid-America," it opened the state's first shafts in 1855 and later served mines in Kentucky. Coal continued comprising some 38% of freight tonnage through the post-World War II period.

After doing its part assisting the United States in the Civil War focus shifted towards further expansion. The first extensions occurred west of Chicago along what eventually became the famous Iowa Division.

After reaching Dunleith on June 11, 1855 officials eyed Iowa with two goals in mind; access to additional agricultural traffic and establishing a much-coveted connection into Omaha, Nebraska, eastern terminus of the transcontinental Union Pacific then under construction.

The first step in this plan was carried out during October of 1867 when the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad was leased.

The last run of Illinois Central's "Governor's Special" (Chicago - Springfield), still powered by classic E6A's, is seen here at Springfield, Illinois on the eve of Amtrak (April 30, 1971). The train's accommodations included a Palm Grove Cafe and coaches. Richard Wallin photo.

The last run of Illinois Central's "Governor's Special" (Chicago - Springfield), still powered by classic E6A's, is seen here at Springfield, Illinois on the eve of Amtrak (April 30, 1971). The train's accommodations included a Palm Grove Cafe and coaches. Richard Wallin photo.Expansion

The D&P began with its April 28, 1853 chartering. By the time IC took control the road had opened a respectable network from Dubuque to Iowa Falls (143 miles) with a branch to Waverly. Its promoters' original goal was Sioux City and this effort was continued under IC, which reached that point on July 8, 1870.

After a bridge over the Mississippi River opened into Dubuque in December of 1868 (at a cost of $1.05 million) through service was enjoyed all of the way into Chicago via trackage rights over the Galena & Chicago Union (predecessor of the Chicago & North Western) east of Freeport (IC later switched this connection to the Chicago & Iowa, a Burlington predecessor, before finishing its own line into the Windy City).

Before further expansion could take place, new ownership arrived in the form of Edward Harriman, who was elected to the company's board of directors in 1883. Harriman, of course, became a legend guiding Union Pacific out of bankruptcy and extending Southern Pacific's reach.

He also held stakes in the Chicago & Alton, Central of Georgia, and Erie Railroad among others. His leadership unquestionably led to Illinois Central's greatest era. Hitting the ground running he purchased the D&P outright in 1887 then formed the Fort Dodge & Omaha Railroad during 1898 to complete the route into Omaha/Council Bluffs.

This task was accomplished the following year on December 18, 1899. There was also further expansion across the Hawkeye State; Sioux Falls, South Dakota was reached in 1887 followed by a nearby branch to Onawa a year later. Also in 1888 service to Cedar Rapids was initiated when a branch opened to that point from Manchester.

Illinois Central's southbound "Panama Limited," led by E7A #4015, hustles through southern Mississippi circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Central's southbound "Panama Limited," led by E7A #4015, hustles through southern Mississippi circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.While all of this was ongoing the company completed one of its most important extensions, closing the gap between Freeport, Illinois and Chicago. (The initial east-west connection, linking its Charter Lines, occurred during July of 1877 when IC acquired the 111-mile Gilman, Clinton & Springfield running from Gilman to Springfield via Clinton.)

A subsidiary known as the Chicago, Madison & Northern Railroad began construction soon after its incorporation during July of 1886, opening two years later in August of 1888. As part of the 112-mile project an additional 59-mile branch was completed to Wisconsin's capital of Madison.

The IC's expansion south of Cairo carried a much more complicated corporate history. Almost all of its growth into Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama was the result of acquisition.

It began following the Panic of 1873 which left the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern (NOJ&GN) and Mississippi Central (MCRR) in financial ruin.

Together, these two systems offered a direct link into New Orleans, totaling 548 miles. The IC acquired both at a bargain between March (NOJ&GN) and August (MCRR) of 1877, merging them into the Chicago, St. Louis & New Orleans (CStL&NO) on November 8th.

The NOJ&GN linked New Orleans with Canton, Mississippi while the MCRR connected from the latter point to East Cairo, Kentucky via Jackson, Tennessee. (Each had been built to 5-foot, broad gauge. IC's track forces completed the switch to standard-gauge during a 24-hour period on July 29, 1881.)

All that remained for a direct Gulf Coast route was a bridge spanning the mighty Ohio River at Cairo. Work began on the massive, 4,644-foot span (which included an additional three miles of approaches) in 1886. It was completed three years later on October 29, 1889 at a cost of just under $3 million.

Illinois Central Gulf GP38-2's #9569 and #9572 work the Louisiana & North West interchange at Gibsland, Louisiana, circa 1984. Note the interesting gate which protected the diamond here. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Central Gulf GP38-2's #9569 and #9572 work the Louisiana & North West interchange at Gibsland, Louisiana, circa 1984. Note the interesting gate which protected the diamond here. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.With a unique north-south route linking the Gulf with Chicago and interchanging with virtually every major American railroad in the process, Illinois Central had established itself as one of the country's preeminent carriers by century's end.

Acquisitions

While the CStL&NO completed Illinois Central's primary network, it was only the beginning of a much greater expansion effort across the South. In the following years the following systems were added:

Illinois Central GP9 #9173 rolls through the Monroe and Regent Streets grade crossing next to Camp Randall Stadium in Madison, Wisonsin in October, 1963. Note the 1961 Ford Galaxie waiting for the train to pass. Today, this line is a trail. Rick Burn photo.

Illinois Central GP9 #9173 rolls through the Monroe and Regent Streets grade crossing next to Camp Randall Stadium in Madison, Wisonsin in October, 1963. Note the 1961 Ford Galaxie waiting for the train to pass. Today, this line is a trail. Rick Burn photo.Mississippi & Tennessee

Acquired in May, 1886. This system provided a direct link to Memphis, Tennessee via Grenada. The original IC main line bypassed the city by heading northeasterly to Jackson before turning northeasterly to Fulton, Kentucky.

Louisville, New Orleans & Texas (LNO&T)

Acquired on October 24, 1892, this rather large system turned southwesterly away from Memphis and followed the Mississippi River for a time before heading due south to Vicksburg and Baton Rouge whereupon it finally terminating once more at New Orleans.

Chesapeake & Ohio Southwestern

This system joined the IC network in December of 1893 while legal problems delayed its sale until 1896. The C&OSW was a Collis Huntington property running northeasterly from Memphis to Louisville, Kentucky via Paducah and Princeton.

It also contained a branch to Hopkinsville originally built by the Ohio Valley Railway. Due to its centralized location, IC opened its primary locomotive maintenance and repair facility in Paducah during 1927.

System Map (1968)

Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad

Another noteworthy subsidiary was the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad. It was originally incorporated on February 17, 1882 as a wholly-owned IC property to manage most of the company's assets south of Memphis, most notably the LNO&T.

In Mr. Murray's book he provides a very nice map detailing the Y&MV network, which comprised the main and secondary lines across western Mississippi. During the 1890's two additions provided a pair of corridors into St. Louis; running southeasterly to its main line at Du Quoin, Illinois was the St. Louis, Alton & Terre Haute Railroad leased on October 1, 1895.

IC then picked up the St. Louis, Peoria & Northern's Springfield to East St. Louis corridor in 1899 with freight service launched on December 1st that year. Into the 20th century expansion efforts continued at a frenzied pace under the vision of Harriman and leadership of President Stuyvesant Fish. (Fish was later ousted after a falling out with Harriman in 1906.)

It breached Indiana and acquired a connection to the state's largest city, Indianapolis, by 1906. Next, through a combination of trackage rights, new construction, and acquisition a 216-mile corridor from Jackson, Tennessee to Birmingham was enjoyed by April of 1908.

Central of Georgia Railway

The latter point offered IC an interchange with the Central of Georgia Railway. Through yet more corporate maneuverings, Harriman had placed this southern road under IC control by June of 1909. It was his last significant act as the railroad's leader for he passed away a few months later on September 9th. Under his direction, Illinois Central had blossomed into an impressive 4,547-mile network.

Illinois Central 4-8-2 #2541 was photographed here late in its career at the shops in Paducah, Kentucky, circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Central 4-8-2 #2541 was photographed here late in its career at the shops in Paducah, Kentucky, circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.The Central of Georgia provided an incredible reach into the heart of the South. The CoG largely remained operationally independent although the two roads worked together in many respects, such as scheduled passenger service and a few CoG E8's wearing IC's orange and brown livery.

- The CoG entered receivership as a result of the Great Depression on December 20, 1932. When it finally emerged in 1948 IC had lost its holdings in the 1,500-mile carrier. On June 17, 1963 Southern Railway gained control, eventually integrating it into its network. -

The IC did not see much additional growth during the 20th century's first two decades, delayed in part by World War I and management under the United States Railroad Administration.

During the booming 1920's a series of improvement programs totaling $300 million were carried out including new locomotives, construction of a large classification yard near Chicago (Markham Yard), and a new 169-mile cutoff between Edgewood, Illinois and Fulton, Kentucky (opened in May of 1928) to ease the crushing flow of traffic through southern Illinois.

Final Additions

Two final additions were added during this time: the Gulf & Ship Island Railroad acquired in 1925 running 90 miles from Jackson to Gulfport, Mississippi and the "Vicksburg Route" picked up via lease of the Alabama & Vicksburg and Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific in 1926.

This corridor extended from Meridian, Mississippi due west to Shreveport, Louisiana. The later provided connections with the Cotton Belt (St. Louis Southwestern Railway), Texas & Pacific (Missouri Pacific), and Kansas City Southern.

Modern Network

By 1929 Illinois Central had reached its zenith with a network of 6,721 miles. Its only other addition occurred after the Tennessee Central Railway shutdown on September 1, 1968. Parts of the old TC network were purchased by surrounding larger carriers, including the IC which picked up its main line from Hopkinsville to Nashville.

Due, in part, to the expansive improvements of the 1920's the railroad avoided bankruptcy following the Great Depression and then struggled to keep up with the blitzkrieg of business brought about by World War II.

The IC was quick to experiment with the diesel locomotive (acquiring its first boxcabs from General Electric/Ingersoll-Rand in 1929) as well as the innovative streamliner, unveiling the Green Diamond in 1936. However, with its strong coal traffic, conservative nature, and healthy freight base it was equally slow to retire the iron horse, not doing so until 1961.

It once even considered experimenting with steam turbine technology but ultimately decided against the idea. Further improvement initiatives launched in the 1950's included implementation of centralized traffic control (CTC), heavier rail (up to 131 pounds), further yard modernizations, and implementation of piggyback/trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) service in 1955.

Illinois Central's train #14, the eastbound "Land O'Corn," stopped at Warren, Illinois on a March morning in 1967. Rick Burn photo.

Illinois Central's train #14, the eastbound "Land O'Corn," stopped at Warren, Illinois on a March morning in 1967. Rick Burn photo.Narrow-Gauge Additions

For most large classic railroads, part of their system contained at least one former narrow-gauge property. In many cases the trackage was operated as an insignificant branch or secondary feeder line that decrease in importance over the years. The IC was no different.

According to George Hilton's, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," there were two notables; the Havana, Rantoul & Eastern (HR&E) located in Illinois and the Mobile & North-Western (M&N-W). The former was incorporated in 1873 by Benjamin Gifford to build from Havana to Williamsport, Indiana via Rantoul, the lawyer's hometown.

By 1879, including additional subsidiaries, his 3-foot road had reached West Lebanon, Indiana to the east (and a connection with the Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific [WStL&P], predecessor of the modern Wabash) and Le Roy, Illinois (here, an interchange was established with the Indianapolis, Bloomington & Western, which later became part of New York Central's Peoria & Eastern).

The entire purpose of the venture was to bypass the IC, which Gifford felt was providing his town unfair freight rates. In 1881 Jay Gould's WStL&P gained control but after his Wabash into receivership in 1884, IC stepped in and purchased the property in 1886.

A year later it was converted to standard gauge and became just another agricultural branch. It was abandoned in stages from 1937 through 1982.

The Mobile & North-Western began life on July 20, 1870 as a grand scheme to run 320 miles from Mobile, Alabama to Helena, Arkansas. Unfortunately, like most such plans funding ran out long before anything of significance had been accomplished.

By 1880 the northernmost 31 miles was finished from Helena to Clarksdale, Mississippi although a bridge spanning the Mississippi River was never built (ferries were utilized until its abandonment in 1973).

In October of 1889 the Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railway (LNO&T) purchased the small road, subsequently removed the section from Eagle Nest to Clarksdale, and converted the property to standard gauge.

In 1892 the LNO&T came under the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley's control. In 1912 the section from Eagle Nest to Jonestown was also abandoned. After ferry service ceased the remaining Lula - Johnestown spur was taken up by Illinois Central Gulf in 1983.

Interestingly, even into the diesel era the company's freight locomotives remained orthodox in appearance wearing a standard black livery with white trim and the famous green diamond logo. Only the passenger equipment's orange and brown scheme provided a dash of color.

The business of railroading became increasingly difficult by the 1960's due to competition from other transportation modes, rising costs, and strict federal regulation. To survive these tough times IC's management did what several others were doing, going the route of a holding company.

The idea was that by placing the railroad in this paper corporation and acquiring other companies (using the railroad's assets) which offered a higher rate of return, greater profits could be achieved.

Illinois Central Industries was launched in 1963 and as Mr. Stover notes branched out into everything from the American Brake Shoe Company to Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers Of Chicago.

Illinois Central GP9s, led by #9219, with Train 14, the "Land O' Corn," near Popular Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois; March, 1967. Rick Burn photo.

Illinois Central GP9s, led by #9219, with Train 14, the "Land O' Corn," near Popular Avenue in Elmhurst, Illinois; March, 1967. Rick Burn photo.The railroad's modest nature also changed at this time under the management of William Johnson. In 1966 he replaced the classic but subtle black and white livery with a bold orange and white scheme. In addition, the revered green diamond logo was dropped for a "split rail" emblem.

It featured the T-rail's cross-section within a black circle; the rail was split down the middle, roughly forming an "I" (with a dot above) and "C." Historians have viewed Johnson's leadership with mixed feelings; he carried many fresh ideas but also believed in the failed holding company philosophy.

Its primary issue was that whatever success the parent company may enjoy the railroad's problems remained (high costs and low returns). The next questionable move involved merger with smaller rival Gulf, Mobile & Ohio.

Illinois Central E7A #4007 is ahead of train #8, "The Creole," at Central Station in Memphis, Tennessee on April 16, 1963. Rick Burn photo.

Illinois Central E7A #4007 is ahead of train #8, "The Creole," at Central Station in Memphis, Tennessee on April 16, 1963. Rick Burn photo.Passenger Trains

The Illinois Central's primary Chicago terminal was Central Station, regarded as one of the city's six great facilities (others being Grand Central Station, Union Station, Dearborn Station, La Salle Street Station, and Northwestern Terminal).

It replaced a stub-end facility located at Randolph Street which could no longer handle growing capacity. Central Station was located along the lakefront, situated at the southwestern corner of Roosevelt Road and Michigan Avenue (and just two blocks east of Dearborn Station). Construction began in 1892 and it opened in 1893.

Sometimes an overlooked component of the IC was its electrified commuter lines. As part of Chicago's Lake Front Ordinance of 1919, IC agreed to remove all grade crossings within the city and energize its suburban lines.

The 1,500-volt, direct-current system was inaugurated on August 7, 1926. Until diesels were introduced this electrification also included freight operations, served by four steeple-cab (B-B) motors (97-ton), manufactured by Baldwin (later sold to the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend). Today, the electrification remains in operation under Metra.

Chickasaw: (Memphis - St. Louis/Chicago)

Daylight: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Delta Express: (Memphis - Vicksburg)

Hawkeye: (Chicago - Sioux City)

Iowan: (Chicago - Sioux City)

Irvin S. Cobb: (Louisville - New Orleans)

Kentucky Cardinal: (Louisville - Memphis)

Land O' Corn: (Chicago - Waterloo, Iowa)

Louisiane: (Chicago/St. Louis - New Orleans)

Magnolia Star: (Chicago - New Orleans)

Mid-American: (Chicago - Memphis)

Night Diamond: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Planter: (Louisville - Memphis)

Seminole: (Chicago - Jacksonville, Florida)

Southwestern Limited/Northeastern Limited: (Meridian - Shreveport)

Illinois Central piggyback trailers, advertising the railroad's classic slogan, at Fort Wayne, Indiana; July, 1958. Rick Burn photo.

Illinois Central piggyback trailers, advertising the railroad's classic slogan, at Fort Wayne, Indiana; July, 1958. Rick Burn photo.Illinois Central Gulf

The Rebel Route served many of the same markets as IC but over a network with just 2,700 miles. Despite the potential hazards officials felt the union was necessary in light of the growing merger movement. The two roads formally joined on August 10, 1972., creating the 9,500-mile Illinois Central Gulf.

While the new company's gross revenues rose its expenses outpaced earnings and by the early 1980's ICG was in danger of entering receivership.

Perhaps its greatest blessing turned out to be passage of the 1980 Staggers Act which greatly de-regulated the industry. Now free to more easily abandon or sell large segments of trackage, leadership under Harry Bruce did just that.

The ICG made six large sales that decade:

- In 1984 it sold 100 miles of the Iowa Division to new short line startup Cedar Valley Railroad.

- A year later 737 miles of the primarily ex-GM&O trackage in Mississippi and Alabama was let go to create the Gulf & Mississippi.

- In 1985 the remainder of the Iowa Division formed the Chicago, Central & Pacific (this new regional was owned by John Haley who also controlled the Cedar Valley short line).

- Three sales in 1986 created MidSouth Railroad (it utilized 418 miles of the Meridian-Shreveport line and extension to Gulfport), Indiana Rail Road (acquired the 100-mile line to Indianapolis), and Paducah & Louisville (purchased the 287 miles between its namesake cities).

- Finally, in May of 1987 the Chicago, Missouri & Western picked up most of the old Chicago & Alton (GM&O) between Kansas City, St. Louis, and Chicago totaling 631 miles.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company/Alco

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| C636 | 1100-1105 | 1968 | 6 |

Electro-Motive Corporation/Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD70 | 1000-1039 | 1995 | 40 |

| GP40 | 3000-3074 | 1966-1970 | 75 |

| GP40X | 3075 | 1965 | 1 |

| E6A | 4000-4004 | 1940-1941 | 5 |

| E7A | 4005-4017 | 1946-1948 | 13 |

| E7B | 4100-4103 | 1946 | 4 |

| E8A | 4018-4033 | 1950-1953 | 16 |

| E8B | 4104-4105 | 1952 | 2 |

| E9A | 4034-4043 | 1954-1961 | 10 |

| E9B | 4106-4109 | 1956-1957 | 4 |

| SD40 | 6000-6005 | 1967 | 6 |

| SD40A | 6006-6023 | 1969-1970 | 18 |

| SD40-2 | 6030-6033 | 1975 | 4 |

| GP7 | 8800-8801, 8850-8851, 8900-8911, 8950-8981 | 1950-1953 | 48 |

| GP9 | 9000-9257, 9300-9389 | 1954-1959 | 348 |

| GP18 | 9400-9428 | 1960-1963 | 29 |

| GP28 | 9428-9440 | 1964 | 13 |

| SW1 | 9014-9032 | 1939-1951 | 19 |

| NW2 | 9150-9166 | 1939-1945 | 17 |

| TR2 | 9203A/B-9208A/B (Cow-Calf) | 1940-1949 | 6 |

| TR1 | 9250A/B-9215A/B | 1941 | 2 |

| SW7 | 9300-9319, 9400-9429 | 1950 | 50 |

| SW9 | 9320-9334, 9430-9484 | 1951-1952 | 70 |

| GP38AC | 9500-9519 | 1970 | 20 |

| GP38-2 | 9600-9639 | 1974 | 40 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U30B | 5001-5005 | 1967 | 5 |

| U33C | 5050-5059 | 1968 | 10 |

Steam Roster

Illinois Central E7A #4004 has recently departed Chicago's Central Station and is just south of Randolph Street Station during October of 1967. Soldier Field can be seen in the background. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Central E7A #4004 has recently departed Chicago's Central Station and is just south of Randolph Street Station during October of 1967. Soldier Field can be seen in the background. American-Rails.com collection.Canadian National Takeover

It was an incredible series of sales which reduced ICG's network to just 2,887 miles but the effort worked. In a final blow to the idea of holding companies, the railroad was spun-off as an independent once more on January 1, 1989. In the process it dropped the "Gulf" and became, once more, Illinois Central.

With a network that contained just a third of the original mileage under ICG, a much slimmer IC spent the 1990's reducing its operating ratio while earning increasingly greater profits. It also made a nearly unprecedented move for a Class I, reacquiring former trackage.

In January of 1996 it bought out the Chicago, Central & Pacific to regain access to Omaha. A few years earlier it had attempted a similar move with the MidSouth Railroad but was unsuccessful. IC's greatly-reduced but equally strategic system made it a prime target of a much larger railroad.

The Canadian National eyed the company as a means of reaching the Gulf Coast and gaining new markets in the process. The deal was finalized in 1998 and CN took control on July 1, 1999.

The importance of the IC network cannot be understated as its primary routes remain an integral part of Canadian National.

In addition, its Chicago commuter network is still operated by Metra while Amtrak has resumed the City of New Orleans between Chicago and New Orleans. In another interesting twist, all of the through corridors the railroad spun-off during the 1980's remain in active service.

Timetables (1952)

Recent Articles

-

Pennsylvania Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 05:19 PM

And among Everett’s most family-friendly offerings, none is more simple-and-satisfying than the Ice Cream Special—a two-hour, round-trip ride with a mid-journey stop for a cold treat in the charming t… -

New York Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:12 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Massachusetts Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:09 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 12:02 PM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

New York Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:56 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:51 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Kentucky Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 11:49 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Indiana Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 06, 26 10:18 AM

The Indiana Rail Experience's "Indiana Ice Cream Train" is designed for everyone—families with young kids, casual visitors in town for the lake, and even adults who just want an hour away from screens… -

Maryland Ice Cream Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:07 PM

Among WMSR's shorter outings, one event punches well above its “simple fun” weight class: the Ice Cream Train. -

North Carolina Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 01:28 PM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Indiana Beer Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 11:26 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Ohio Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:36 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

North Carolina Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:34 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Virginia Ale Tasting Train Rides

Feb 05, 26 10:30 AM

Among Virginia Scenic Railway's lineup, Ales & Rails stands out as a fan-favorite for travelers who want the gentle rhythm of the rails paired with guided beer tastings, brewery stories, and snacks de… -

Colorado St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 01:52 PM

Once a year, the D&SNG leans into pure fun with a St. Patrick’s Day themed run: the Shamrock Express—a festive, green-trimmed excuse to ride into the San Juan backcountry with Guinness and Celtic tune… -

Utah St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 12:19 PM

When March rolls around, the Heber Valley adds an extra splash of color (green, naturally) with one of its most playful evenings of the season: the St. Paddy’s Train. -

Washington Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:28 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Connecticut Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:11 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

Maryland Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 04, 26 10:06 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Washington St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 04:30 PM

If you’re going to plan one visit around a single signature event, Chehalis-Centralia Railroad’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is an easy pick. -

California Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:25 PM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Alabama Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:13 PM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Tennessee St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 01:04 PM

If you want the museum experience with a “special occasion” vibe, TVRM’s St. Patrick’s Day Dinner Train is one of the most distinctive ways to do it. -

Indiana Bourbon Tasting Trains

Feb 03, 26 11:13 AM

The French Lick Scenic Railway's Bourbon Tasting Train is a 21+ evening ride pairing curated bourbons with small dishes in first-class table seating. -

Pennsylvania Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 03, 26 09:35 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Massachusetts Dinner Train Rides On Cape Cod

Feb 02, 26 12:22 PM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) has carved out a special niche by pairing classic New England scenery with old-school hospitality, including some of the best-known dining train experiences in the… -

Maine's Dinner Train Rides In Portland!

Feb 02, 26 12:18 PM

While this isn’t generally a “dinner train” railroad in the traditional sense—no multi-course meal served en route—Maine Narrow Gauge does offer several popular ride experiences where food and drink a… -

Oregon St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:16 PM

One of the Oregon Coast Scenic's most popular—and most festive—is the St. Patrick’s Pub Train, a once-a-year celebration that combines live Irish folk music with local beer and wine as the train glide… -

Connecticut Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:13 PM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on the… -

Massachusetts St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 12:12 PM

Among Cape Cod Central's themed events, the St. Patrick’s Day Brunch Train stands out as one of the most fun ways to welcome late winter’s last stretch. -

Florida's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:53 AM

Each year, Day Out With Thomas™ turns the Florida Railroad Museum in Parrish into a full-on family festival built around one big moment: stepping aboard a real train pulled by a life-size Thomas the T… -

California's Thomas The Train Rides

Feb 02, 26 11:45 AM

Held at various railroad museums and heritage railways across California, these events provide a unique opportunity for children and their families to engage with their favorite blue engine in real-li… -

Nevada Dinner Train Rides At Ely!

Feb 02, 26 09:52 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could step through a time portal into the hard-working world of a 1900s short line the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely is about as close as it gets. -

Michigan Dinner Train Rides At Owosso!

Feb 02, 26 09:35 AM

The Steam Railroading Institute is best known as the home of Pere Marquette #1225 and even occasionally hosts a dinner train! -

Virginia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 01:08 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

Maryland ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:29 PM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

North Carolina St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:21 PM

If you’re looking for a single, standout experience to plan around, NCTM's St. Patrick’s Day Train is built for it: a lively, evening dinner-train-style ride that pairs Irish-inspired food and drink w… -

Connecticut St. Patrick's Day Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:19 PM

Among RMNE’s lineup of themed trains, the Leprechaun Express has become a signature “grown-ups night out” built around Irish cheer, onboard tastings, and a destination stop that turns the excursion in… -

Alabama's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 12:17 PM

The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum (HoDRM) is the kind of place where history isn’t parked behind ropes—it moves. This includes Valentine's Day weekend, where the museum hosts a wine pairing special. -

Florida's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:25 AM

For couples looking for something different this Valentine’s Day, the museum’s signature romantic event is back: the Valentine Limited, returning February 14, 2026—a festive evening built around a tra… -

Connecticut's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:03 AM

Operated by the Valley Railroad Company, the attraction has been welcoming visitors to the lower Connecticut River Valley for decades, preserving the feel of classic rail travel while packaging it int… -

Virginia's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 11:00 AM

If you’ve ever wanted to slow life down to the rhythm of jointed rail—coffee in hand, wide windows framing pastureland, forests, and mountain ridges—the Virginia Scenic Railway (VSR) is built for exac… -

Maryland's Valentine's Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:54 AM

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR) delivers one of the East’s most “complete” heritage-rail experiences: and also offer their popular dinner train during the Valentine's Day weekend. -

Massachusetts ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Feb 01, 26 10:27 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc…