Kankakee Belt Route, NYC's Illinois Division

Published: December 8, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Kankakee Belt Route was one of the Midwest’s most interesting “quiet” main lines—a strategic bypass around Chicago that never became a famous name in its own right, yet played an important role in moving grain, merchandise, and run-through freight between eastern and western carriers.

Its story weaves together several predecessor lines, New York Central’s efforts to avoid Chicago congestion, changing transportation economics on the Illinois River, and the slow retrenchment of the late 20th century that left much of the route abandoned while a core segment still works today as a freight artery.

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound New York Central "Gemini" freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at the once very busy interlocking in North Judson, Indiana on November 27, 1966. These pool trains operated over the Kankakee Belt in August 1966 from Rock Island's Silvis Yard to Elkhart, Indiana via DePue, Illinois. The trains were short-lived and operated for only about a year. Rick Burn photo.

Rock Island F7A #114 leads an eastbound New York Central "Gemini" freight on the Kankakee Belt Line at the once very busy interlocking in North Judson, Indiana on November 27, 1966. These pool trains operated over the Kankakee Belt in August 1966 from Rock Island's Silvis Yard to Elkhart, Indiana via DePue, Illinois. The trains were short-lived and operated for only about a year. Rick Burn photo.Origins: The “3 I” and the Kankakee River Valley

What later became known as the Kankakee Belt Route began life in the late 19th century under other names. The most important of these was the Indiana, Illinois & Iowa Railroad—commonly called the “3 I” route. Built westward from Streator, Illinois, to North Judson, Indiana, in 1881, and extended on to South Bend in 1894, the 3 I formed a roughly east-west corridor south of the Chicago region.

The line threaded the Kankakee River Valley, crossing a patchwork of farm towns and small industrial communities. In Illinois it touched places such as Kankakee, Dwight, Streator, Lostant, and Ladd before reaching Zearing, where it connected with Chicago, Burlington & Quincy. In Indiana it passed through or near communities like North Liberty, Walkerton, Hamlet, Knox, North Judson, San Pierre, Shelby, and Schneider, ultimately reaching South Bend.

Corporate control soon shifted. Through stock ownership by NYC affiliates Lake Shore & Michigan Southern and Michigan Central, the Indiana, Illinois & Iowa—and related properties such as the Chicago, Indiana & Southern (CI&S)—fell under NYC influence. As the system was rationalized in the early 20th century, this cross-country line was integrated into New York Central’s Illinois Division and promoted collectively as the Kankakee Belt Line, or Kankakee Belt Route, in reference both to the river valley it followed and the growing rail belt it formed around Chicago.

A Chicago Bypass for the New York Central

NYC’s primary main lines into Chicago—such as the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern main line along Lake Michiganf—were heavily congested. As freight interchanges with western carriers grew, NYC saw value in directing some traffic around the worst of the Chicago terminal tangle. The Kankakee Belt Route was ideally placed for that purpose.

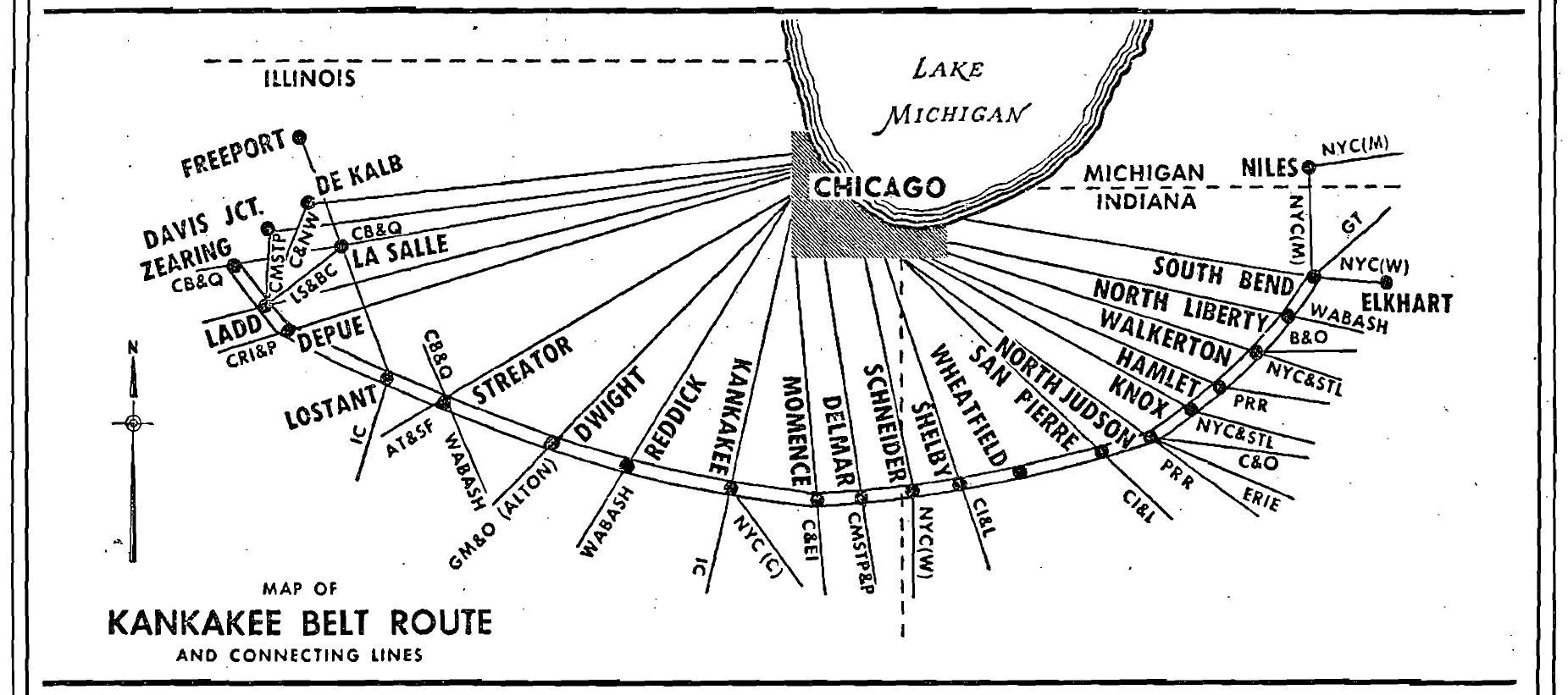

From South Bend on the east to Zearing on the west, the line formed an arc south of the city, with numerous junctions where NYC could hand traffic to or receive traffic from western roads. In 1964, for example, the Illinois section of the Kankakee Belt connected with:

- Milwaukee Road at places like Litchfield and Sun River Terrace

- Chicago & Eastern Illinois at Momence

- Illinois Central and NYC itself at Kankakee

- Wabash at Reddick

- Gulf, Mobile & Ohio (ex-Alton) at Dwight

- Santa Fe and CB&Q at Streator

- Illinois Central at Lostant

- Rock Island at De Pue

- Milwaukee Road, C&NW, and LaSalle & Bureau County (“The Bee”) at Ladd

- CB&Q at Zearing

Similarly, in Indiana it linked with Grand Trunk, B&O, Nickel Plate, Pennsylvania, Erie, C&O, and Monon at various towns between South Bend and Schneider.

This web of connections is why later commentators would call it one of the best potential Chicago bypass lines of its day—capable of funneling freight between practically every major western road and the New York Central without ever entering the Chicago terminal area.

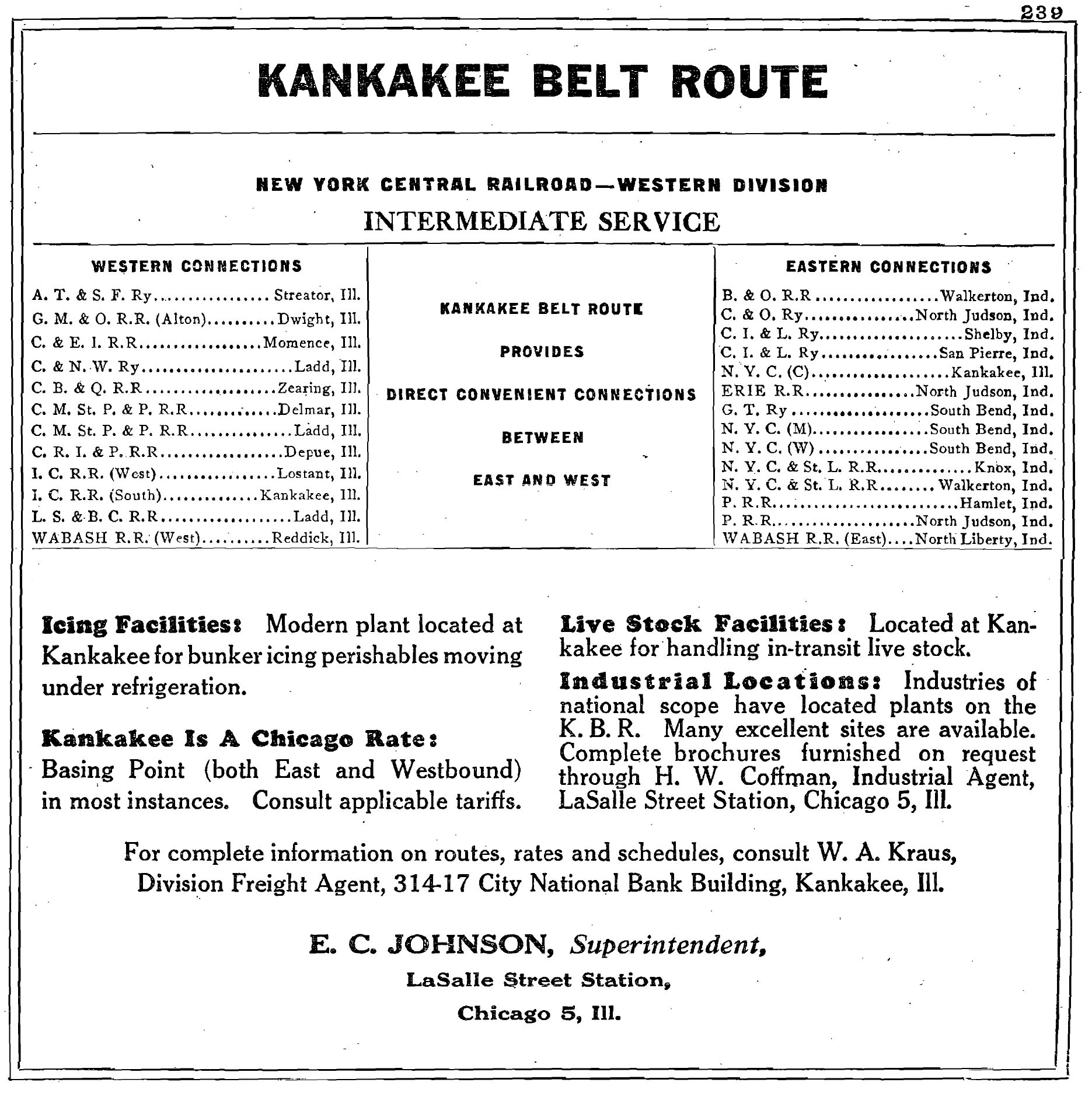

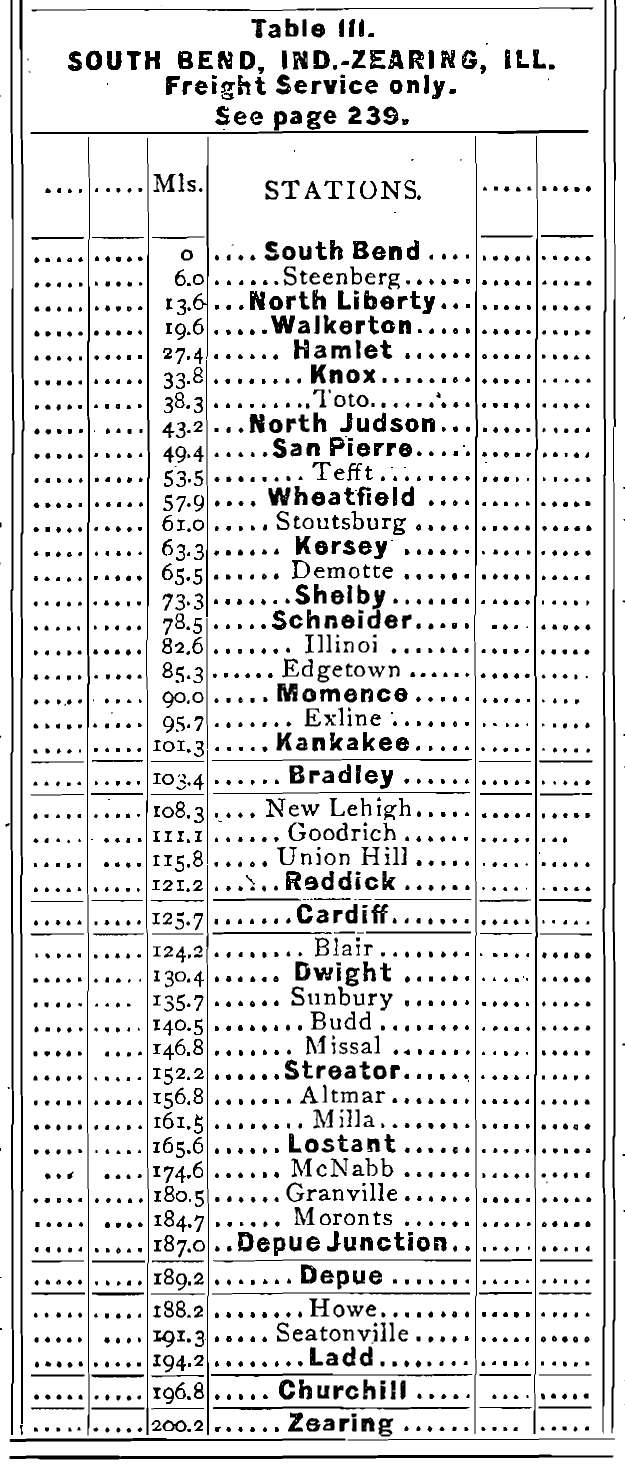

A timetable of the line from August, 1952. American-Rails.com collection.

A timetable of the line from August, 1952. American-Rails.com collection.Traffic and Operations: Grain, Merchandise, and Pool Freight

Although the Kankakee Belt Route never achieved the fame of NYC’s Water Level Route, it handled a mix of traffic that made it an important secondary main line.

Grain and the Illinois River

West of Kankakee, the route paralleled the Illinois River across northern Illinois. This placed it squarely in rich corn country, and the line became an outlet to eastern markets for grain elevators and small towns along its path. Grain moved eastward to NYC’s system and on to mills, elevators, and industrial users in the East.

For a time, this grain traffic helped justify heavy investment in the route, including bridges, yards, and interlocking plants. NYC advertised the Kankakee Belt as an efficient path for agricultural products, with the Illinois River valley providing a direct flow of grain from farm to railhead.

Merchandise and Through Freight

The line also handled merchandise freight, coal, and other commodities in both directions. While some historians question how much true overhead “bypass” traffic used the route before the Penn Central era, there were notable run-through arrangements. Rock Island and New York Central, for example, interchanged at Streator, and there is evidence of pool freight trains operating over the Belt to reach yards such as Argentine on the Santa Fe.

In addition, the NYC and Rock briefly operated the hotshot "Gemini" trains along the route for about a year in the mid-1960s.

The Kankakee yards, located west of the city, became a focal point for these operations, with classification work and interchange moves taking place alongside local switching. The yard, built prior to 1922, was busy enough to be a key feature of NYC’s presence in the area.

Passenger and Local Service

Passenger traffic over the Kankakee Belt was always secondary compared with NYC’s main lines. Local trains and gas-electric “doodlebugs” served small towns along the route, providing connections to larger cities. Period photographs show NYC doodlebugs at junction points, reflecting a time when even relatively remote branches had passenger service.

However, the populations of many intermediate towns were modest, and by mid-20th century most passenger services dwindled under competition from highways and buses. Freight, especially grain and interchange traffic, remained the primary reason for the line’s existence.

Competition from the River: The Mechling Barge Case

One of the most important turning points for the Kankakee Belt Route came not from another railroad but from improvements to the Illinois River waterway.

In the mid-1930s, major upgrades—deeper and wider locks at places like Lockport—allowed the river to handle larger tows and, later, even tank landing ships (LSTs) built by Chicago Bridge & Iron at Seneca during World War II. These improvements transformed the river into a powerful competitor for bulk traffic, especially grain.

By the 1950s, barge operators were undercutting rail rates. Prior to 1957, for example, combined barge-plus-rail movements (barge from Illinois River ports to Chicago, then rail east) offered significantly lower costs per hundredweight of corn than all-rail shipments originating on the Kankakee Belt and moving directly east on NYC.

The resulting rate disputes culminated in the Mechling Barge Lines v. United States case, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964. That decision became one episode in the long fight between railroads and inland waterways over rate structures and competitive parity. For the Kankakee Belt Route, the practical effect was clear: a portion of its traditional grain business was siphoned away by barges, weakening one of the line’s core traffic bases.

Penn Central, Conrail, and Contraction

The merger of New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad into Penn Central in February, 1968 briefly gave the Kankakee Belt new visibility. Contemporary accounts suggest that Penn Central established a pair of dedicated through freights over the route around 1969 to better exploit its Chicago-bypass potential, though it is debatable how long these trains survived in Penn Central’s troubled early years.

When Conrail was created in 1976 to take over the operations of several bankrupt eastern carriers—including Penn Central—the Kankakee Belt found itself competing internally with other Conrail lines and routings. By this time:

- Passenger service was gone.

- Grain had alternatives via truck and barge.

- Many interchanges with now-struggling western roads had lost their former importance.

Conrail, under pressure to eliminate redundancy and focus on profitable corridors, began to trim. Portions of the old Kankakee network, especially those that overlapped with better-engineered or more heavily used lines, were downgraded or abandoned.

One major casualty was the north-south line from Gary, Indiana, through Schneider to Danville, Illinois. Under Conrail this became known as the Danville Secondary, and the segment from Schneider south to Danville—about 76 miles—was taken out of service and abandoned in 1994.

Bridges, Breaks, and Short Lines

The Illinois River crossing near DePue became a dramatic symbol of the route’s fragmentation. The swing bridge over the river was struck by a barge in the 1960s, caught fire, and the bridge tender was killed in the incident. While temporary repairs allowed continued use for a time, the bridge was ultimately removed in the early 1980s. Once the bridge was gone, the continuous east-west route was effectively severed.

West of the river, much of NYC’s former track toward Ladd was pulled up, though Illinois Railway later acquired portions between Depue and Ladd, and, in 2004, extended its holdings from a wye with BNSF at Zearing through Ladd and Spring Valley to LaSalle. Thus, fragments of the old Kankakee Belt lived on as short-line territory serving local customers and industrial sites along the Illinois River.

In Indiana and the eastern part of the route, similar fragmentation occurred. East of Schneider toward South Bend, the mainline was cut back. By the 1980s, the track between South Bend and the NIPSCO generating station at Wheatfield was removed, and what remained in South Bend itself was reduced to lightly used industrial trackage serving only a handful of customers, in conjunction with other ex-PRR and Wabash routes.

Norfolk Southern and the Modern Kankakee Belt

Despite all these losses, the Kankakee Belt did not disappear entirely. Conrail’s western segment between Streator, Illinois, and the Indiana state line survived as a valuable connector, and when Conrail was divided in 1999, Norfolk Southern inherited this portion. NS continues to operate the line today.

In modern times, this NS segment typically sees roughly eight to ten trains per day between the BNSF (ex-Santa Fe) main line at Streator and NS interchanges and facilities to the east. The line still functions as a Chicago bypass of sorts, handling:

- Run-through traffic between NS and BNSF or other western roads

- Grain and agricultural traffic from elevators and terminals along the line

- General merchandise and unit trains as traffic patterns demand

The western end now effectively terminates near the site of the former Illinois River bridge, east of DePue, while the eastern end is integrated into NS’s broader network in Indiana.

At Kankakee itself, the legacy of railroading remains visible. While the famous Illinois Central depot downtown is more directly associated with IC’s main line and Amtrak service, the broader city landscape—yards, industrial sidings, and remaining NS trackage—still reflects the days when the Kankakee Belt was a high-utility bypass line in the New York Central System.

Legacy and What Might Have Been

Rail historians occasionally point to the Kankakee Belt Route as one of those “what if” lines: a corridor that, had it been preserved intact, could have played a major role in 21st-century freight flows around Chicago.

Today’s railroads struggle with congestion in the region, and various bypass schemes—some involving new construction, others leveraging existing lines—have been proposed. A fully intact Kankakee Belt, with its web of junctions to western carriers, might have been an extremely valuable piece of that puzzle.

Instead, its story reflects the realities of mid- and late-20th-century railroading: competition from barges and trucks, regulatory battles over rates, the consolidation and bankruptcy of major carriers, and the ruthless cost-cutting of the Conrail era. Sections without strong local traffic or strategic value were trimmed away, leaving only those pieces that could still earn their keep.

Yet the route’s influence lives on. The surviving NS segment continues to move freight across the Midwest, honoring the original purpose of the line as a connector and bypass. Short lines and regional carriers work bits of the old alignment, serving elevators and industries that still depend on rail.

And in the collective memory of railfans—and in the landscapes of towns like North Judson, Streator, Kankakee, and Zearing—the Kankakee Belt Route remains a reminder of a time when railroads could bend around Chicago, linking east and west on a belt of steel along the Kankakee River Valley.

Recent Articles

-

Kentucky Dinner Train Rides At Bardstown

Jan 31, 26 02:29 PM

The essence of My Old Kentucky Dinner Train is part restaurant, part scenic excursion, and part living piece of Kentucky rail history. -

Arizona Dinner Train Rides From Williams!

Jan 31, 26 01:29 PM

While the Grand Canyon Railway does not offer a true, onboard dinner train experience it does offer several upscale options and off-train dining. -

Washington "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 12:02 PM

Whether you’re a dedicated railfan chasing preserved equipment or a couple looking for a memorable night out, CCR&M offers a “small railroad, big experience” vibe—one that shines brightest on its spec… -

Georgia "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:55 AM

If you’ve ridden the SAM Shortline, it’s easy to think of it purely as a modern-day pleasure train—vintage cars, wide South Georgia skies, and a relaxed pace that feels worlds away from interstates an… -

Maryland ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:49 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

Colorado ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:40 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa's ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:34 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Minnesota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:24 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Georgia ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:23 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 31, 26 11:15 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

Colorado "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 11:02 AM

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad is the kind of trip that feels tailor-made for railfans and casual travelers alike, including during Valentine's weekend. -

Massachusetts "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:37 AM

The Cape Cod Central Railroad (CCCR) blends classic New England scenery with heritage equipment, narrated sightseeing, and some of the region’s best-known “rails-and-meals” experiences. -

California "Valentine's" Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:34 AM

Operating out of West Sacramento, this excursion railroad has built a calendar that blends scenery with experiences—wine pours, themed parties, dinner-and-entertainment outings, and seasonal specials… -

Kansas Dinner Train Rides In Abilene

Jan 30, 26 10:27 AM

If you’re looking for a heritage railroad that feels authentically Kansas—equal parts prairie scenery, small-town history, and hands-on railroading—the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad delivers. -

Georgia's Dinner Train Rides In Nashville!

Jan 30, 26 10:23 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could slow down, trade traffic for jointed rail, and let a small-town landscape roll by your window while a hot meal is served at your table, the Azalea Sprinter delivers tha… -

Georgia "Wine Tasting" Train Rides In Cordele

Jan 30, 26 10:20 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel like… -

Arizona ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:18 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Arkansas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 30, 26 10:17 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

Wisconsin ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:26 PM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Illinois Dinner Train Rides At Monticello

Jan 29, 26 02:21 PM

The Monticello Railway Museum (MRM) is one of those places that quietly does a lot: it preserves a sizable collection, maintains its own operating railroad, and—most importantly for visitors—puts hist… -

Vermont "Dinner Train" Rides In Burlington!

Jan 29, 26 01:00 PM

There is one location in Vermont hosting a dedicated dinner train experience at the Green Mountain Railroad. -

California ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:50 PM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Alabama ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:46 PM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

Washington's "Wine Tasting" Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 12:39 PM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 29, 26 11:12 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail. -

Duffy's Cut: A Forgotten Railroad Tragedy

Jan 29, 26 11:05 AM

Duffy's Cut is an unfortunate incident which occurred during the early railroad industry when 57 Irish immigrants died of cholera during the second cholera pandemic. -

Wisconsin Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:47 PM

This article delves deep into the passenger and commuter train services available throughout Wisconsin, exploring their history, current state, and future potential. -

Connecticut Passenger Rail

Jan 28, 26 11:30 PM

Connecticut's passenger and commuter train network offers an array of options for both local residents and visitors alike. Learn more about these services here. -

South Dakota ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:29 PM

While the state currently does not offer any murder mystery dinner train rides, the popular 1880 Train at the Black Hills Central recently hosted these popular trips! -

Wisconsin ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 12:23 PM

Whether you're a fan of mystery novels or simply relish a night of theatrical entertainment, Wisconsin's murder mystery dinner trains promise an unforgettable adventure. -

Florida ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:18 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards. -

Texas ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:08 AM

This article invites you on a metaphorical journey through some of these unique wine tasting train experiences in Texas. -

New York ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:05 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 11:04 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

Indiana ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:59 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:57 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Minnesota Valentine's Train Rides

Jan 28, 26 10:51 AM

One of the most charming examples of MTM’s family-friendly programming is “The Love Train,” a Valentine’s-themed day that blends short train rides with crafts, treats, and playful activities inside th… -

Georgia Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 10:03 PM

Georgia offers a variety of train services, from historic scenic routes to modern commuter trains serving the Atlanta metropolitan area. -

Illinois Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 02:49 PM

Learn more about Illinois's current passenger rail options, ranging from Amtrak to the Twin Cities' light rail service. -

Pennsylvania Passenger Rail

Jan 27, 26 02:40 PM

Here is a detailed, statewide look at the passenger rail services you can use today—focusing on intercity (long-distance and regional) options, primarily operated by Amtrak—plus the major commuter and… -

New Mexico ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 01:19 PM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 01:10 PM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

Pennsylvania ~ Wine Tasting ~ Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 12:05 PM

Wine tasting trains are a unique and enchanting way to explore the state’s burgeoning wine scene while enjoying a leisurely ride through picturesque landscapes. -

West Virginia's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 11:57 AM

West Virginia, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes and rich history, offers visitors a unique way to explore its rolling hills and picturesque vineyards: wine tasting trains. -

Iowa Valentine's Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 10:22 AM

While the Boone & Scenic Valley's calendar is packed with seasonal events, few are as popular—or as tailor-made for couples—as the Valentine Dinner Train. -

Texas Valentine's Train Rides

Jan 27, 26 09:44 AM

On Valentine's Day, the Grapevine Vintage Railroad has become one of the Dallas–Fort Worth area’s most charming "micro-adventures" - and, on Valentine’s Day, one of the region’s most memorable date ni… -

Missouri ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 26, 26 01:21 PM

Missouri, with its rich history and scenic landscapes, is home to one location hosting these unique excursion experiences. -

Washington's ~ Murder Mystery ~ Dinner Train Rides

Jan 26, 26 01:15 PM

This article delves into what makes murder mystery dinner train rides in Washington State such a captivating experience. -

Utah's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 26, 26 12:48 PM

Utah, a state widely celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty and dramatic landscapes, is also gaining recognition for an unexpected yet delightful experience: wine tasting trains. -

Vermont's - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Jan 26, 26 12:40 PM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides.