Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (Rock Island)

Last revised: March 26, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The fabled Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad was a legend in its own time. A Might Fine Line was immortalized in song when Clarence Wilson, a member of the Rock Island's Colored Booster Quartet (an employee choir group from the railroad's Biddle Shops in Little Rock, Arkansas) wrote "Rock Island Line" in 1929.

A few different versions sprang up in the succeeding years, the most famous of which was recorded by icon Johnny Cash in 1970.

Unfortunately, for all the Rock's fame it was not quite as glamorous in reality. It carried problems tracing back to its earliest years and served cities its competitors already reached.

The Rock never "ran down into New Orleans" as Mr. Cash sang and struggled after the company's greatest leader, John D. Farrington, retired. In 1964, a merger was agreed upon with Union Pacific to assure the Rock's survival.

Alas, there was much opposition to this union and as the Interstate Commerce Commission dragged its feet the railroad physically collapsed.

In late 1974, when the agency finally gave its blessing UP was no longer interested. With few options left the Rock Island entered bankruptcy and was liquidated in 1980. In one of the industry's great ironies, most of the railroad's principal routes survive today.

Photos

Rock Island F9Am #4158, circa 1975; another former Union Pacific F3A (#1416-A/#1522) the railroad had rebuilt to F9 specs (numbered 522) before being sold to the Rock in 1972. It's interesting that the lettering was painted right over the portholes. By the 1970s the Rock was in desperate need of motive power but could not afford new units so it acquired outdated, first-generation power at a bargain price from UP. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island F9Am #4158, circa 1975; another former Union Pacific F3A (#1416-A/#1522) the railroad had rebuilt to F9 specs (numbered 522) before being sold to the Rock in 1972. It's interesting that the lettering was painted right over the portholes. By the 1970s the Rock was in desperate need of motive power but could not afford new units so it acquired outdated, first-generation power at a bargain price from UP. American-Rails.com collection.History

From a nostalgic standpoint many would argue the Rock Island was the greatest of all grangers and it's often hard to dispute that belief.

The railroad offered wonderful bucolic scenes in postwar years of tired covered wagons negotiating rickety and weed-covered trackage to serve a local customer along a rural Midwestern branch line.

While such scenes provided fascinating subjects for the camera they more vividly illustrated the railroad's plight. Agriculture was always the Rock's lifeblood and the two carried a symbiotic relationship.

This was never made clearer than during the 1970's when states like Iowa offered assistance to rebuild crumbling branch lines for continued rail service.

The company's history began like so many others in the Midwest, launched in the mid-19th century to help a small town reach its potential.

According to Bill Marvel's wonderful title, "Rock Island Line," a group of businessmen spent an evening in June of 1845 planning a railroad of 75 miles to link Rock Island, Illinois (across the Mississippi River from Davenport, Iowa) with LaSalle.

What was known as the Rock Island & La Salle Rail Road Company, officially incorporated on February 27, 1847, would work in conjunction with canal and riverboat operators to move freight and passengers into Chicago.

Rock Island & La Salle Rail Road

Unfortunately, this ambitious lot did not have the needed funding to begin construction right away, the bane of so many such projects. They were forced to go about it the old fashioned way, acting as salesmen going door to door selling stock across the countryside.

Raising money in this manner normally carried mixed results but enthusiasm for the railroad turned out to be quite high and by November of 1850 the needed $300,000 had been secured.

When the group sought an engineer for surveying a route they were told extending the line into Chicago offered the best chance of success.

Rock Island E8A #644 leads one of the late era "Rocket" services through Chicago; August, 1973. Kevin Scanlon photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island E8A #644 leads one of the late era "Rocket" services through Chicago; August, 1973. Kevin Scanlon photo. American-Rails.com collection.Chicago & Rock Island Railroad

The eager group quickly agreed to this new plan and renamed their company accordingly, as the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad (C&RI). The individual who had made the proposal was Henry Farnam, already well-known for his work on the Michigan Southern Railroad building towards Chicago.

This system went on to form part of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, a future component of the mighty New York Central. Farnam's help also provided the CR&I with strong financial backing. In seemingly no time at all a project with an uncertain future was now on solid ground.

Rock Island FA-1's, with #129 closest to the photographer, layover in Denver, Colorado, circa 1965. The CRI&P would send its entire fleet of sixteen "A" units (145-160) to EMD in the mid-1950s whereupon they were upgraded with 567C's and renumbered. Some were additionally given Blomberg trucks (like the trailing unit) from trade-in FT's. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island FA-1's, with #129 closest to the photographer, layover in Denver, Colorado, circa 1965. The CRI&P would send its entire fleet of sixteen "A" units (145-160) to EMD in the mid-1950s whereupon they were upgraded with 567C's and renumbered. Some were additionally given Blomberg trucks (like the trailing unit) from trade-in FT's. American-Rails.com collection.4-4-0 "Rocket"

Construction commenced in August of 1852 and rapidly progressed westward from Chicago. In his book, "Classic American Railroads," historian Mike Schafer notes when the initial segment was completed the 4-4-0 Rocket, amid much celebration, pulled the road's first train between Chicago and Joliet on October 10, 1852.

As work continued the line was completed more than a year ahead of the schedule when rail service opened to Rock Island on February 22, 1854. It proved an immediate success and promoters felt so good about their prospects expansion was underway before the C&RI's completion.

On February 5, 1853 the Mississippi & Missouri Rail Road had been chartered to build from Davenport to Council Bluffs. As the book "Iowa Railroads" (the essays of Frank Donovan, Jr., edited by H. Roger Grant) points out, the M&M also planned branches to Muscatine and the Minnesota border via Cedar Rapids; the former opened on November 20, 1855 but the latter was not reached until some years later.

Within two years of reaching Rock Island the Mississippi River was bridged and direct service into Davenport, Iowa opened on April 23, 1856.

Rock Island 2-10-2 #3053 leads a westbound freight near Tucumcari, New Mexico on May 4, 1940. American-Rais.com collection.

Rock Island 2-10-2 #3053 leads a westbound freight near Tucumcari, New Mexico on May 4, 1940. American-Rais.com collection.With the pace of construction it appeared the C&RI would soon establish itself as one of the Midwest's premier systems. However, just as quickly work slowed considerably due to financing and a national recession.

As the M&M languished its competitors, notably the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Chicago & North Western, eyed their own extension to Council Bluffs while expanding in other directions far beyond the Windy City.

With Congressional passage of the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, subsequently signed into law by President Lincoln on July 1st, the Union Pacific Railroad was established as the eastern leg of the Transcontinental Railroad. Its goal was to build west from Omaha, a city located directly across the Missouri River from Council Bluffs.

Rock Island E6A #630 is seen here at Silvis, Illinois, circa 1973, wearing a special "Gold Wing" livery to honor Electro-Motive's 50th anniversary manufacturing locomotives (1922-1972). She continued to handle commuter assignments until the end of operations in 1978 when she was subsequently stored at Silvis. Today, the E6 is preserved by the Iowa Northern Railway and cosmetically restored. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island E6A #630 is seen here at Silvis, Illinois, circa 1973, wearing a special "Gold Wing" livery to honor Electro-Motive's 50th anniversary manufacturing locomotives (1922-1972). She continued to handle commuter assignments until the end of operations in 1978 when she was subsequently stored at Silvis. Today, the E6 is preserved by the Iowa Northern Railway and cosmetically restored. American-Rails.com collection.Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad

Despite the traffic potential a connection there offered the M&M advanced little in the succeeding years and was further delayed by the Civil War. The road then slipped into bankruptcy and was reorganized as the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad in July of 1866.

Hope for prosperity returned, however, when new leadership under John Tracy sought the Rock's completion. A date of June 1, 1869 was set for this to occur and if it not met the road would lose its land grants across Iowa.

Logo

From its end-of-track at Iowa City rails extended westward, reaching Council Bluffs just in time on May 11, 1869 and a day after the Transcontinental Railroad held formal opening ceremonies at Promontory Summit, Utah. Despite the significance of this event the Rock was not the first to arrive.

A Chicago & North Western subsidiary had completed its own route in January of 1867, followed by a Chicago, Burlington & Quincy predecessor two years later.

Richard Overton points out in his authoritative book, "Burlington Route: A History Of The Burlington Lines," predecessors of the Kansas City, St. Joseph & Council Bluffs (1870) provided the Burlington its initial link to Council Bluffs, opening on November 25, 1869.

This was followed by a more direct link via Burlington, Iowa and the Burlington & Missouri River Rail Road completed on January 3, 1870.

At A Glance

Chicago - Omaha, Nebraska Omaha - Colorado Springs/Denver, Colorado Davenport, Iowa - Tucumcari, New Mexico Bureau Junction - Peoria, Illinois Minneapolis - Kansas City Manly-Burlington, Iowa Cedar Rapids (Vinton), Iowa - Sioux Falls, South Dakota Keokuk, Iowa - Bear Lake, South Dakota Tucumcari - Memphis Herington, Kansas - Houston Little Rock, Arkansas - Eunice, LouisianaKansas City - St. Louis |

|

Freight Cars: 26,690 Passenger Cars: 646 |

|

It is rather ironic that despite being the first to bridge the mighty Mississippi the Rock Island was one of the last to reach Council Bluffs.

Its late arrival carried severe repercussions throughout the years as its interchange business with Union Pacific was only ever a fraction of that enjoyed by C&NW, the Omaha road's primary Chicago freight connector. This singular issue also caused the drawn out fight over UP's planned merger with Rock Island nearly a century later.

Rock Island GP40 #4713 at the railroad's Silvis, Illinois hump yard and terminal. Date not recorded. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island GP40 #4713 at the railroad's Silvis, Illinois hump yard and terminal. Date not recorded. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

After Council Bluffs was reached, Rock Island embarked upon a great expansion although playing second-fiddle throughout the Midwest became a common theme.

It also arrived in other important cities after its competitors reaching Kansas City in 1879 over rails of the Hannibal & St. Joseph (Burlington) and did not achieve access into the Twin Cities until its 1885 acquisition of the 368-mile Burlington, Cedar Rapids & Northern (which also reached eastern South Dakota at Sioux Falls and Waterton).

The Rock's growth in the latter 19th century was started under John Tracy and continued through Hugh Riddle. A myriad of small systems were added at this time; names like the Keokuk & Des Moines; Des Moines, Indianola & Missouri; Newton & Monroe; and the Des Moines & Fort Dodge.

As Mr. Donovan's book notes, no railroad dominated the Hawkeye State like the Rock. It came to operate a network of 2,075 miles, nearly double that of Chicago & North Western (1,053 miles).

Rock Island FA-1 #158 and another unit lead Extra 158 on the Illinois Division, circa 1953. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island FA-1 #158 and another unit lead Extra 158 on the Illinois Division, circa 1953. American-Rails.com collection.Under Tracy, the Rock launched a secondary extension heading southwesterly from Davenport. Known as the Chicago & South Western Railway construction began in 1869 from the end-of-track at Washington, Iowa with intentions of reaching Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway

By the spring of 1872 the line was complete after a bridge opened over the Missouri River. With expansion throughout Iowa occurring at a rapid pace the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad and its many subsidiaries were merged into a new company known as the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway.

In 1883 a change in leadership occurred when Ransom Cable took the reigns; under his direction the Rock Island grew far beyond its regional status. He began by acquiring the aforementioned BCR&N and then set off for the Western Frontier via a new subsidiary known as the Chicago, Kansas & Nebraska.

It was chartered in December of 1886 to build from St. Joseph (a decision which forever left Leavenworth along a relatively inconsequential branch line), head towards Wichita, and reach Denver, Colorado along the Front Range.

With new sources of financing secured and business booming the project commenced quickly. Construction had only just begun when permission was granted to extend beyond Wichita to the Gulf Coast at Galveston, via East Texas and Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

Rock Island F7A #115 leads a westbound through Lincoln, Nebraska, circa 1960. Note the trailers riding in converted gondolas. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island F7A #115 leads a westbound through Lincoln, Nebraska, circa 1960. Note the trailers riding in converted gondolas. American-Rails.com collection.Choctaw Route

The CK&N carried out some of the fastest construction ever witnessed. Following only two years of work there were more than 1,100 miles ready for service by 1889 reaching Denver, Topeka, and Wichita.

There was also an extension to El Reno, Oklahoma while a direct route from Denver to Omaha was established via Belleville, Kansas and Lincoln, Nebraska.

In 1891 Rock Island boasted a network of nearly 4,000 miles and had blossomed into a major Midwestern system. Further growth slowed for about a decade until new leadership through the Reid-Moore Syndicate in 1901 reignited the process.

Under their direction the fabled "Choctaw Route" was established as well as the "Golden State Route" completed from Liberal, Kansas to a connection with the El Paso & Northeastern Railroad at Santa Rosa, New Mexico in February of 1902.

The EP&N was acquired by the El Paso & Southwestern during the summer of 1905, which all became part of the Southern Pacific in 1924.

It is somewhat surprising that the Rock did not continue beyond New Mexico and establish its own transcontinental route given the company's strong financing at the time and the syndicate's desire to do so. There was some additional westward survey work performed but apparently officials were happy to carry the title of "Pacific" in name-only.

Rock Island GP7R #4491, a rebuild acquired from Precision National, appears to be carrying out switching chores in the summer of 1975. Location not listed. This unit was built as Wabash GP7 #471. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island GP7R #4491, a rebuild acquired from Precision National, appears to be carrying out switching chores in the summer of 1975. Location not listed. This unit was built as Wabash GP7 #471. American-Rails.com collection.When the "Choctaw Route," built by the Choctaw, Oklahoma & Gulf, was completed to Tucumcari, New Mexico in 1910 the "Golden State Route" south of that point was leased to the EP&SW. The Choctaw was another important corridor, a southern gateway linking the Southwest and Southeast.

It curved eastward from Tucumcari, headed to Amarillo and cut across Oklahoma and Arkansas before terminating at Memphis, Tennessee. Back along the Rock Island's eastern fringes service opened to St. Louis via Kansas City and finally accessed Galveston when the Trinity & Brazos Valley Railway was leased from the Colorado & Southern in 1906 (later known as the Burlington-Rock Island Railroad).

South of Little Rock, Arkansas the syndicate tried to establish a through route to New Orleans but only made it as far as Eunice, Louisiana where it had to settle upon an interchange with Missouri Pacific. While Reid-Moore's efforts saw the railroad balloon into a network of 8,328 miles they also embarked upon a disastrous scheme of trying to leverage Rock Island's strong earnings power in financing a true transcontinental network.

The incredibly complex and expensive boondoggle failed, and along with it the railroad, which entered receivership in 1915. It was reorganized on June 24, 1917 as the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad with the original system still intact.

Unfortunately, the company's newfound freedom was short-lived. After the United Stated entered World War I the Rock, and the entire industry, was placed under federal control on December 28, 1917 through the United States Railway Administration. There it remained until being returned to private management on February 28, 1920.

The road spent the "Roarin' 20's" enjoying the decade's strong traffic and carried out some infrastructure improvements but its perennial infrastructure issues (light rail, poor ballasting, insufficient bridges, and circuitous routes) were not resolved when the stock market crashed in the fall of 1929.

These problems, coupled with the country's economic condition, caused a second bankruptcy on June 7, 1933.

This time, recovery was not as fast but a bright spot appeared, new president John Dow Farrington. The receivers brought him in to fix the problems and return the railroad to profitability. Without question, Farrington was the Rock Island's greatest leader.

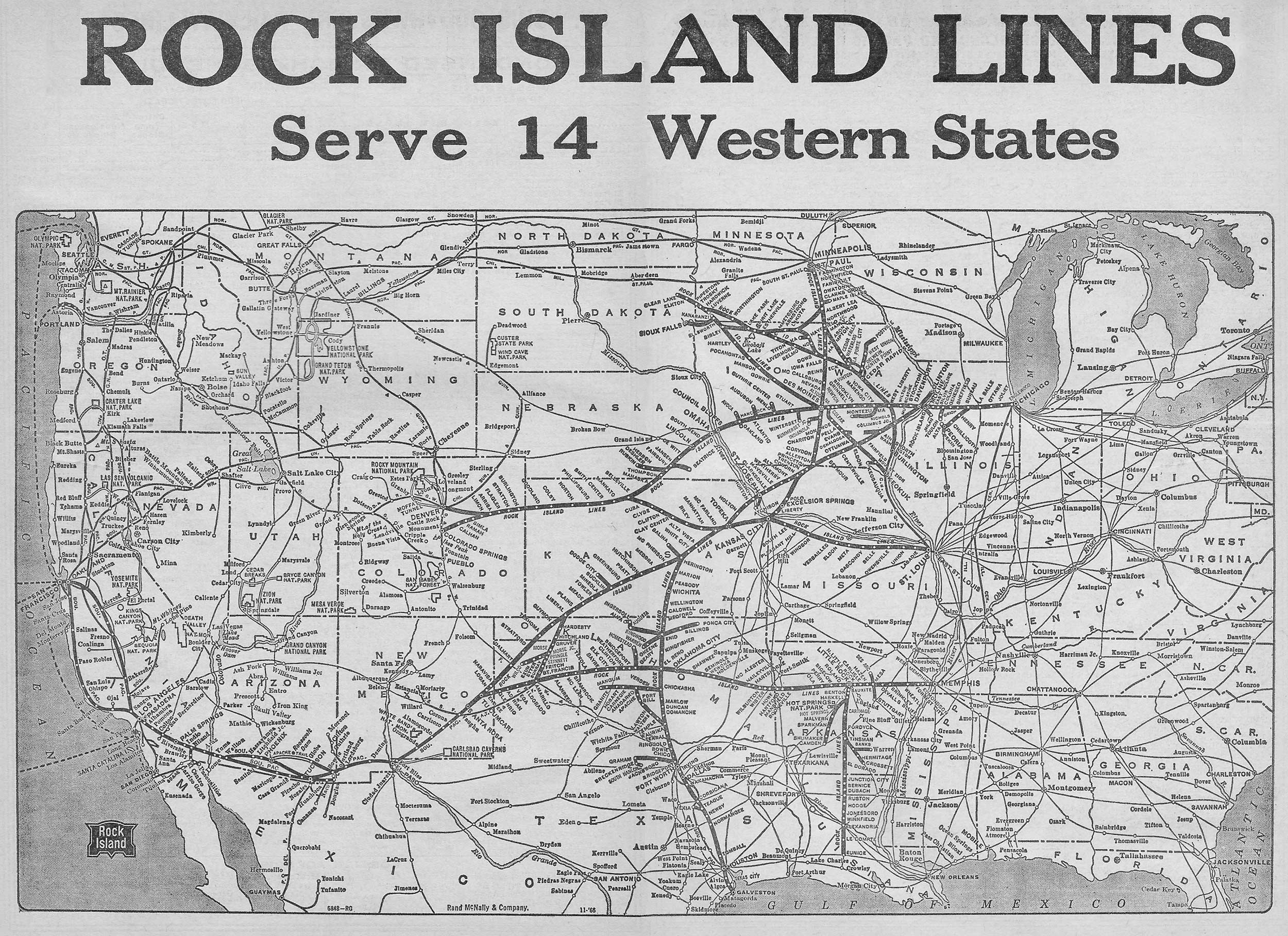

System Map

Modern Network

Farrington was a no-nonsense manager, always on the hunt for ways of increasing efficiency and cutting waste. He loathed ignorance and brought quick retribution upon anyone who could not thoroughly answer questions.

Farrington's high-rail equipped Ford sedan became a common, and dreaded, sight as it traveled around the Rock Island network hunting potential problems.

Under his direction the railroad set about a system-wide infrastructure improvement program by replacing ties, pouring tons of new ballast, rebuilding bridges, laying heavy, 112+ pound rail on main lines, straightening bottlenecks, purchasing diesels, and expanding centralized traffic control/automatic block signaling systems.

Within only a few years the results were being felt; annual revenues increased from $66 million in 1934 to $82 million in 1937.

This number further increased to $96 million by 1941 and just after World War II had reached $178 million by 1947. A now healthy Rock Island exited receivership on January 1, 1948 as the road's future appeared very bright.

Farrington not only upgraded the property but was also a streamliner proponent. As John Kelly notes in his book, "Rock Island Railroad: Photo Archive," several new trains debuted from the late summer through early fall of 1937 including the Texas Rocket (August 29th), Peoria Rocket (September 19th), Des Moines Rocket (September 25th), Minneapolis-Kansas City Rocket (September 29th), and Kansas City-Denver Rocket (October 18th).

These trains were adorned in an attractive livery of two-tone maroon with silver/aluminum pulled by matching locomotives, a unique four-axle passenger model from Electro-Motive known as the TA (#601-606).

The Rocket fleet continued to grow in the succeeding years when the Twin Star Rocket debuted on January 15, 1945, followed by the Rocky Mountain Rocket on November 12, 1939, and finally the transcontinental Golden State.

The latter had been operated jointly with Southern Pacific for years but was re-inaugurated as a streamliner in January of 1948. The modernization continued through the 1950's as steam was retired by 1954 and modern classification yards were built, most notably at Silvis, Illinois.

Decline

Unfortunately, the 1950's were a tough decade for the entire industry which dealt with declining traffic brought about through increased competition (highways and airlines) and a 1958 national recession. The Rock's legendary leader retired in 1955 but was replaced by Downing Jenks, an equally accomplished railroader.

Unfortunately, his tenure was short-lived when he left for the Missouri Pacific. This brought Farrington back briefly before his death in 1961 at which time R. Ellis Johnson assumed the presidency. As the 1960's dawned the Rock was showing signs of trouble; in a region overbuilt with railroads it relied heavily on dwindling agricultural traffic.

To make matters worse it was not heavily diversified in other areas such as coal, manufacturing, or petrochemicals and did not enjoy the C&NW's healthy interchange business through the Council Bluffs/Omaha gateway.

At this time, talks with a merger between Milwaukee Road and Southern Pacific were briefly carried out before discussions with Union Pacific began.

In September of 1964 UP formally applied to acquire the Rock Island. Its relationship with the Chicago & North Western at the time was strained and the CRI&P would provide it a direct link into Chicago.

For a complete history of the Rock's final years, Greg Schneider's "Rock Island Requiem," is strongly recommended. The author superbly articulates how the company collapsed during its final decade and a half of operation.

1970s Struggles

The Rock Island's final decade of operation could best be summed up as grim, both physically and internally. As Doug Kroll's photo at Joliet, Illinois illustrates, the motive power was in sorry condition.

The Rock was too poor to upgrade its roster except for some new Electro-Motive units, and cheaper General Electric "U-boats," picked up during the 1960's and 1970's.

In its final days it was still running dilapidated covered wagons dating back to just after World War II. In addition, E6A #630, continued working the commuter pool throughout the 1970s, a locomotive which had been outshopped in October of 1941! (Today, it is preserved.)

The physical plant was an equally sad situation with rotten ties, insufficient rail, slow orders, and derailments a common occurrence throughout the system.

If the railroad was an up-to-date, modern operation it quite likely would have been profitable. One of president John Ingram's initiatives in cutting costs and revamping the company's image was adoption of a cheaper light blue and white livery with "The Rock" emblazoned across locomotives and equipment.

A tired Rock Island U25B, #228, lays over at the Inver Grove engine house in St. Paul, Minnesota during the summer of 1977. By this time, the railroad was struggling to maintain enough power to even meet remaining freight demand. American-Rails.com collection.

A tired Rock Island U25B, #228, lays over at the Inver Grove engine house in St. Paul, Minnesota during the summer of 1977. By this time, the railroad was struggling to maintain enough power to even meet remaining freight demand. American-Rails.com collection.In the absence of new power the company carried out its so-called Capital Rebuild Program on venerable Geeps to extend their service lives.

During a power shortage in the early '70s it also picked up elderly F9's from Union Pacific while even first-generation Alco road units, re-engined with Electro-Motive model 567 prime movers, continued to see service throughout that decade. To say the least, it's fleet was eclectic. Perhaps more than any other state, Iowa was most proactive in saving the Rock's operations within its borders.

It formed the Iowa Energy Policy Council in 1973, whose duties included (among other things) saving branch lines for continued rail service.

While the state ultimately set aside several million dollars to carry out these improvements (which also included rehabbing lines of the Milwaukee Road and Burlington Northern), interestingly, it was the shippers themselves which sometimes ponied up funds for rebuilding the branches.

There has been great blame laid on the Interstate Commerce Commission for dragging out the proceedings that eventually led to the company's collapse. In truth, the ICC was only part of the problem.

When the merger was announced, Chicago & North Western's Ben Heineman immediately challenged the UP-Rock Island marriage. Instead, he proposed his own takeover of the Rock or at least a three-way union with the Milwaukee Road.

Rock Island U25Bs #235 and #237 lead a westbound on the Kansas City Terminal as the train rolls past the Sheffield Interlocking Tower, circa 1967. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island U25Bs #235 and #237 lead a westbound on the Kansas City Terminal as the train rolls past the Sheffield Interlocking Tower, circa 1967. American-Rails.com collection.If the UP-Rock merger was approved the C&NW would stand to lose considerable interchange business through the Omaha gateway so its opposition was justified. As the hearings wore on and the years passed the Rock Island simply fell apart.

As Mr. Schneider notes, in 1959 the railroad was still a well-respected corporation boasting gross annual revenues of $219.5 million with a ranking of 22nd in Fortune magazine's Top Fifty Transportation Companies. Barely two decades later the picture had changed dramatically as the road carried a stunning annual deficit of $400 million when it was liquidated in 1980.

Rock Island U30C #4582 and SD40-2 #4795, circa 1975. From the Mike Bledsoe collection. American-Rails.com

collection.

Rock Island U30C #4582 and SD40-2 #4795, circa 1975. From the Mike Bledsoe collection. American-Rails.com

collection.As the railroad came apart it is also truly perplexing why Union Pacific did not spend the capital for infrastructure improvements, or at least enough to maintain operations, considering the planned merger. The Rock's officials asked multiple times for such funds but were always denied.

Union Pacific was the wealthiest railroad in the country at the time (and still-so today); in 1966 its net income, before taxes, was an impressive $109.7 million. As part of the takeover plan UP had agreed to spend $200 million on such improvements but only after the marriage was finalized. Nearly a decade passed before the ICC officially granted approval on November 8, 1974.

As a condition of the merger, Rio Grande would acquire the Rock's Omaha-Denver main line and Santa Fe would pick up most of its Choctaw Route (Memphis - Amarillo) as well as be required to takeover the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad.

In addition others would be given additional traffic rights and interchange gateways to help shield them from potential traffic losses. Unfortunately, by then the Rock's property was in pathetic condition and UP was no longer interested. With no where else to turn the railroad entered bankruptcy protection on March 17, 1975.

The Rock Island's final years were sad to witness as the road attempted in vain to produce a profitable railroad beneath decaying infrastructure and a mountain of debt.

It tried to apply for governmental assistance, notably through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), but with Washington busy with the Penn Central mess the Rock's situation was largely ignored (as was that of the Milwaukee Road, which entered bankruptcy in 1977). Adding insult to injury the railroad was still running passenger trains.

Rock Island GP7R #4444, following her rebuild by Morrison-Knudsen in Boise, Idaho, was on her way back to home rails when photographed here in Salt Lake City on April 24, 1975. Ken Ardinger photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island GP7R #4444, following her rebuild by Morrison-Knudsen in Boise, Idaho, was on her way back to home rails when photographed here in Salt Lake City on April 24, 1975. Ken Ardinger photo. American-Rails.com collection.It could not afford the entry feet to join what became the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) on May 1, 1971 and continued operating what was dubbed the Peoria Rocket and Quad Cities Rocket until service was finally suspended on December 31, 1978. The immediate elimination of these trains could have saved the railroad $1 million annually.

The state of Illinois also forced it to continue running its money-losing commuter trains throughout the Chicago area. In a dire financial situation it threatened to immediately discontinue these, which were costing the Rock nearly $2 million annually, if the state did not either take over the service or provide a subsidy. Illinois finally relented by at first providing a stipend but eventually took over the services entirely.

"Rock Island Line" (Song)

"Rock Island Line" was a term often used to describe the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific. It almost certainly predated the song although the future ballad would earn the company widespread publicity. As mentioned at the start of this article, the original is credited to Clarence Wilson although its lyrics are not believed to exist.

Throughout the years several versions were released, which greatly deviated from Wilson's said to describe the daily activities of Rock Island's shops in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Rock Island Line gained recognition when musicologist John Lomax recorded the first audio version on September 29, 1934 at the prison farm in Tucker, Arkansas with assistance from Lead Belly (an African American folk/blues musician who's full name was Huddie William Ledbetter).

This version featured elements of the original as well as new lyrics now regarded as the song's "classic" rendition. Lead Belly would go on to sing Rock Island Line numerous times throughout his career. Over the decades many other artists have either sang or released versions including:

Billy Bragg/Joe Henry

Bobby Darin

Boxcar Willie

Chris Thomas King

Dan Zanes and Friends

Devil in a Woodpile

Don Cornell

Eleven Hundred Springs

Eric Church

Gateway Singers

George Harrison/Paul Simon

George Melly

Graham Bonnet

Harry Belafonte

John Lennon

Johnny Cash

Johnny Horton

Little Richard & Fishbone

Lonnie Donegan

Long John Baldry

Mano Negra

Merrill Moore, With Cliffie Stone's Orchestra

Milt Okun

Odetta

Ramblin Jack Elliot

Ringo Starr

Snooks Eaglin

Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee

Stan Freberg

The Brothers Four

The Knitters

The Reverend Peyton's Big Damn Band

The Tarriers

The Washington Squares

The Weavers

Whiskey Howl

Woody Guthrie/Sonny Terry

Johnny Cash, of course, sang the most widely accepted and remembered version of a Rock Island Line. The lyrics are as follows:

Now this here's a story about the Rock Island Line

Well the Rock Island Line she runs down into New Orleans

There's a big tollgate down there

And you know, if you got certain things on board when you go through the tollgate

Well you don't have to pay the man no toll

Well a train driver he pulled up to the tollgate

And a man hollered and asked him what all he had on board and said:

------------------

I got livestock

I got livestock

I got cows

I got pigs

I got sheep

I got mules

I got all livestock

------------------

Well he said you're alright boy, you don't have to pay no toll

You can just go right on through so he went on through the tollgate

And as he went through he started pickin' up a little bit of speed

Pickin' up a little bit of steam

He got on through he turned and looked back at the man he said

------------------

Well I fooled you

I fooled you

I got pig iron

I got pig iron

I got old pig iron

------------------

~ Chorus ~

Down the Rock Island Line she's a mighty good road

Rock Island Line it's the road to ride

Rock Island Line it's a mighty good road

Well if you ride it you got to ride it like you find it

Get your ticket at the station for the Rock Island Line

~ Chorus ~

------------------

Looked cloudy in the west and it looked like rain

Round the curve came a passenger train

Northbound train on a southbound track

He's alright a leavin' but he won't be back

~ Chorus ~

Oh I may be right and I may be wrong

But you're gonna miss me when I'm gone

Well the engineer said before he died

There were two more drinks that he'd like to try

The conductor said what could they be

A hot cup of coffee and a cold glass of tea

~ Chorus ~

Rock Island GP7R #4422, GP7 #1257, and another GP7R lead a mixed freight through the interlocking at Tower 55 in Fort Worth, Texas, circa 1979. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island GP7R #4422, GP7 #1257, and another GP7R lead a mixed freight through the interlocking at Tower 55 in Fort Worth, Texas, circa 1979. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Judge Frank McGarr, who headed the bankruptcy proceedings, had no experience with railroads. However, he was a good manager who understood the importance of the Rock Island's routes despite growing pressure from creditors to liquidate immediately.

McGarr continued delaying liquidation as his team attempted to put together a profitable operation. Alas, time simply ran out.

The railroad greatly needed to rebuild its failing infrastructure (which then totaled just over 7,300 route miles) but there was simply no money to do so. With its financial condition in tatters borrowing was impossible.

Passenger Trains

Choctaw Rocket: (Amarillo - Memphis)

Corn Belt Rocket: (Chicago - Omaha)

Des Moines Rocket: (Chicago - Des Moines)

The Imperial (Consist, History, Photos, Timetable): Operated between Los Angeles and Chicago in conjunction with the Southern Pacific.

Jet Rocket: (Chicago - Peoria)

Kansas City Rocket: (Minneapolis - Kansas City)

Peoria Rockets: (Chicago - Peoria)

Texas Rocket: Originally served Fort Worth and Houston, although later connected Kansas City and Dallas.

Twin Star Rocket: (Minneapolis - Houston)

Quad Cities Rocket: (Chicago - Rock Island)

Zephyr Rocket: Connected Minneapolis and St. Louis in conjunction with the CB&Q.

A very tired Rock Island E8A, #650, has the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket" at Joliet, Illinois in March, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

A very tired Rock Island E8A, #650, has the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket" at Joliet, Illinois in March, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.The final blow came on August 28, 1979 when the Brotherhood of Railway & Airline Clerks, joined by the United Transportation Union, issued a strike and the railroad's fate was sealed.

Their issue dealt with a new national labor wage agreement which they refused to accept. The move essentially put them out of work when McGarr ordered liquidation on January 25, 1980. It was a somber conclusion to a beleaguered road that had fought hard until the end.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA-1 | 145-160 | 1948 | 16 |

| FB-1 | 145B-152B | 1948 | 8 |

| C415 | 415-424 | 1966 | 10 |

| RS2 | 450-454 | 1948 | 5 |

| RS3 | 455-474, 485-499 | 1950-1951 | 35 |

| DL107A | 621, 623 | 1940-1941 | 2 |

| DL105A | 622 | 1940 | 1 |

| DL103A | 625 | 1939 | 1 |

| S2 | 716-729 | 1942-1948 | 14 |

| RS1 | 735-749 | 1941-1944 | 15 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | 760-764 | 1943-1944 | 5 |

| LS-800 | 800-801 | 1950 | 2 |

| S8 | 802-806 | 1952 | 5 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| LWT-12 | 1-3 | 1956-1958 | 3 |

| F2A | 38-49 | 1946 | 12 |

| FTA | 70-73, 70A-73A, 88-99 | 1944-1945 | 20 |

| FTB | 70B-73B, 88B-99B | 1944-1945 | 16 |

| F7A | 100-127, 675-677 | 1949-1951 | 31 |

| F7B | 100B-109B, 120B-123B, 675B-677B | 1948-1951 | 17 |

| GP35 | 300-333 | 1965 | 34 |

| GP40 | 340-396, 4700-4719 | 1966-1970 | 77 |

| FP7 | 402-411 | 1949 | 10 |

| BL2 | 425-429 | 1949 | 5 |

| GP7 | 430-441, 1200-1237, 1250-1311 | 1950-1953 | 112 |

| SW | 500-528 | 1937-1938 | 29 |

| SW1 | 529-546 | 1942-1949 | 18 |

| SW900 | 550-563, 900-914 | 1958-1959 | 29 |

| TA | 601-606 | 1937 | 6 |

| E3A | 625-626 | 1939 | 2 |

| E6A | 627-631 | 1940-1941 | 5 |

| E7A | 632-642 | 1946-1948 | 11 |

| E7B | 632B-642B | 1946-1948 | 11 |

| E8A | 643-656 | 1949-1953 | 14 |

| NW | 700-707 | 1938 | 8 |

| NW2 | 765-774 | 1949 | 10 |

| SW9 | 775-779 | 1953 | 5 |

| SW8 | 811-838 | 1950-1953 | 28 |

| SW1200 | 920-936 | 1965 | 17 |

| SW1500 | 940-949 | 1966 | 10 |

| GP9 | 1312-1332 | 1957-1959 | 21 |

| GP18 | 1256, 1329, 1333-1353 | 1960-1961 | 24 |

| GP38-2 | 4300-4355, 4368-4379 | 1976-1978 | 68 |

| SD40-2 | 4790-4799 | 1973 | 10 |

Fairbanks-Morse

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H15-44 | 400-401 | 1948 | 2 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U33B | 190-199, 285-299 | 1968-1969 | 25 |

| U25B | 200-238 | 1963-1965 | 39 |

| U28B | 240-281 | 1966 | 42 |

| U30C | 4582-4599 | 1973 | 18 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| 10, G-19 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| A-24, A-29 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| B (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| C (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| D (Various) | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| K (Various) | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| N-78 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| P (Various) | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| R-67a/b | Northern | 4-8-4 |

| S-29, S-33 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| S-53 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

Rock Island SD40-2 #4798 with a westbound transfer run at the Hoffman Avenue interlocking in St. Paul, Minnesota, circa 1976. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island SD40-2 #4798 with a westbound transfer run at the Hoffman Avenue interlocking in St. Paul, Minnesota, circa 1976. American-Rails.com collection.Postscript

No single person was at fault for the Rock Island's liquidation; everyone in a leadership position in the last days tried their best to right the ship. As it turns out there was, indeed, a solvent road beneath the mess. Nearly all of the railroad's through routes were ultimately purchased and remain in operation today.

Only one is not, the Choctaw Route (Tucumcari - Memphis). There were negotiations with Arkansas and Oklahoma to purchase 866 miles of the corridor to be operated as the Arkansas-Oklahoma Railroad.

The Trustee set a price of $100 million although the states only wanted to pay $21 million, the salvage value. In the end, the parties were too far apart and the property was abandoned.

Various railroads picked up other segments, including the Iowa Interstate, a 1984 startup which spent a great deal of money and effort to resurrect the Chicago - Omaha main line. Today, it is an extremely successful Class II, regional.

On May 19, 1984 the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad was reorganized as the Chicago Pacific Corporation, a non-operating railroad entity which branched out into the fields of investment and real estate. It began to grow by acquiring the Hoover Corporation in 1985 before being purchased itself by the Maytag Corporation in 1988.

More Reading

Contents

SteamLocomotive.com

Wes Barris's SteamLocomotive.com is simply the best web resource on the study of steam locomotives.

It is difficult to truly articulate just how much material can be found at this website.

It is quite staggering and a must visit!