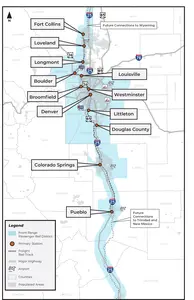

Norfolk & Western Railway: Map, Logo, Rosters, History

Last revised: November 5, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Norfolk and Western’s merger with the Southern in

1982 was fitting for two railroads which spent most of the 20th century as efficient, profitable operations.

From a history tracing back to the 1830s the N&W did not blossom into a great American success story until after 1900.

It acted a conveyor belt of coal moving black diamonds from mines located in southern West Virginia and southwestern Virginia to Norfolk/Newport News.

Before expanding rapidly after the late 1950's its original network contained only slightly more than 2,000 route miles connecting Norfolk with Cincinnati and Columbus.

Historically, the railroad is remembered for many things ranging from its staunch support of the steam locomotive to legendary photographer O. Winston Link who captured its final days of steam in stunning black and white photography.

His work is now considered all but priceless works of art. Today, the N&W's principal lines remain in use under successor Norfolk Southern.

Its once lucrative coal business is not the juggernaut of yore but still sustains the "Thoroughbred Route" through modern times.

Photos

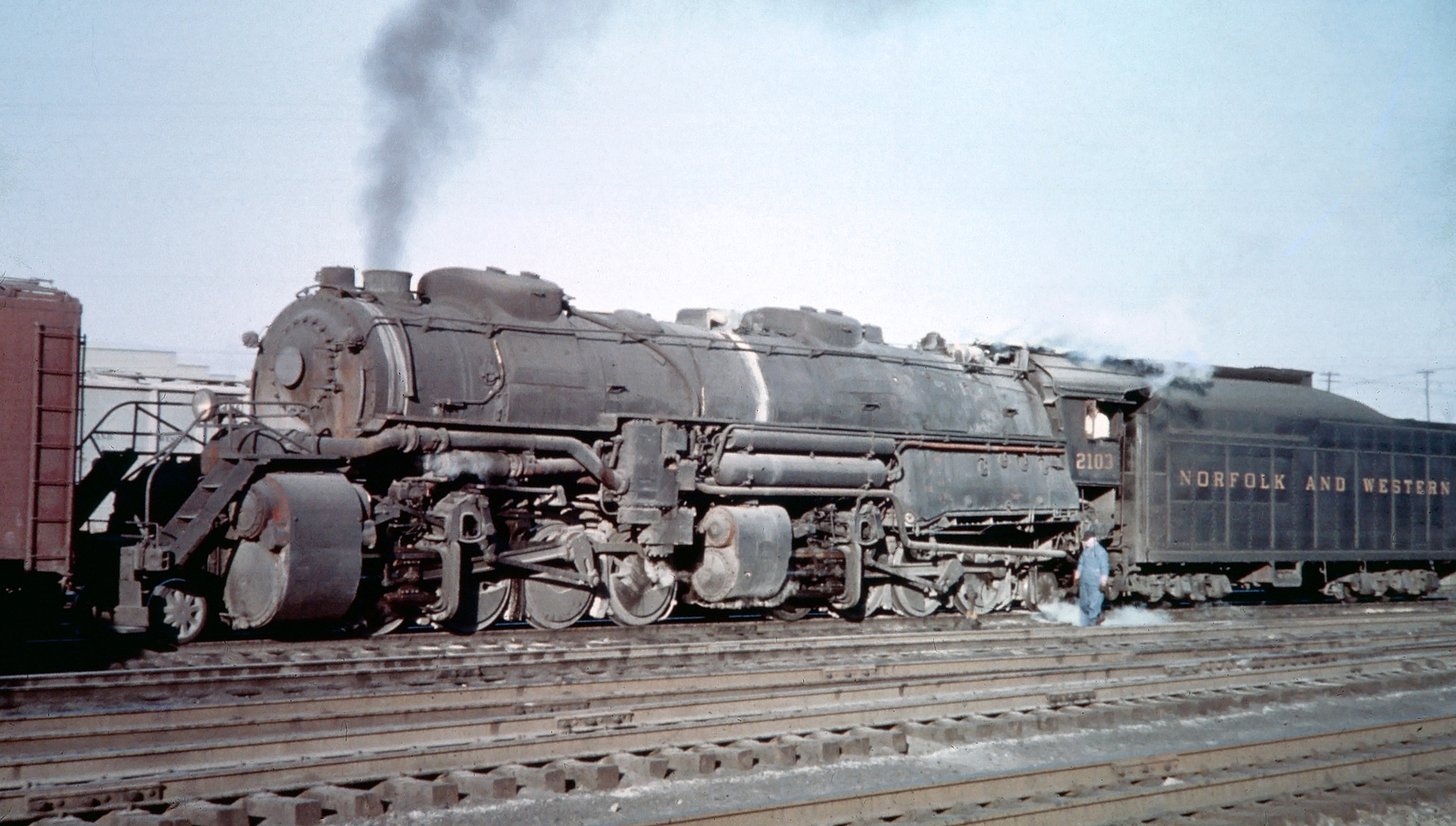

Norfolk & Western 2-8-8-2 #2103 (Y-4a) at Roanoke, Virginia, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Norfolk & Western 2-8-8-2 #2103 (Y-4a) at Roanoke, Virginia, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.History

The origins of the mighty Norfolk & Western begin quite humbly in far eastern Virginia when the General Assembly chartered the City Point Railroad during early 1836. The early industry was still learning its trade and steam power was rudimentary.

However, railroads were proving their worth up and down the east coast from the South Carolina Canal & Rail Road Company serving Charleston, South Carolina to the Baltimore & Ohio linking Baltimore, Maryland.

At A Glance

2128.85 (1952) 8,029 (1965) | |

Lambert's Point (Norfolk), Virginia - Columbus, Ohio Portsmouth - Cincinnati, Ohio Lynchburg, Virginia - Durham, North Carolina Roanoke - Hagerstown, Maryland Roanoke - Winston-Salem, North Carolina Walton - Bristol, Virginia Bluefield, Virginia - Norton, Virginia |

|

Freight Cars: 75,621 Passenger Cars: 251 | |

The City Point opened on September 7, 1838 between its hometown (now known as Hopewell) on the James River to nearby Petersburg, a distance of 9 miles.

During a period in which efficient transportation was limited primarily to slow-moving waterways the new railroad could move freight and passengers at unheard of speeds.

In 1847 the City Point was reorganized as the Appomattox Railroad and acquired by the Southside Railroad (SRR) in 1854.

Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #612 has train #15, the westbound "Cavalier," crossing Friendship Road outside of Shawsville, Virginia on October 23, 1952.

Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #612 has train #15, the westbound "Cavalier," crossing Friendship Road outside of Shawsville, Virginia on October 23, 1952.The latter carrier had been chartered in 1846, initially to build from Petersburg to what is now Blackstone.

According to C. Nelson Harris’s book, “Norfolk & Western Railway Stations And Depots,” the Southside was given its name because its right-of-way traveled south of the James River.

It began construction in 1849 and by 1852 had reached Burkeville, providing an interchange there with the Richmond & Danville (later, Southern Railway).

As the Southside continued westward, intent on reaching Lynchburg, it was faced with a choice of grading a southerly route with easier grades or follow a more circuitous and rugged northerly extension. In another case of money dictating logic the latter corridor was ultimately chosen.

The reasoning was not entirely without merit; the railroad needed funding and the northerly route was enticing because the town of Farmville offered financial incentives to connect their town (common in those times when communities recognized the economic opportunities a railroad brought).

The line was forced to cross the wide Appomattox River, which required a massive span. The High Bridge, completed in 1852, was 2,440 feet in length and rose 125 feet above the water line (today it is part of the High Bridge Trail between Burkeville and Pamplin). The Southside would finish its line to Lynchburg two years later in 1854.

Norfolk & Western F7A #3717 (ex-Wabash #1185) is seen here in Decatur, Illinois on September 25, 1965. The N&W never purchased its own cab units; all were acquired through the 1964 Wabash Railroad merger. Dick Wallin photo/Warren Calloway collection.

Norfolk & Western F7A #3717 (ex-Wabash #1185) is seen here in Decatur, Illinois on September 25, 1965. The N&W never purchased its own cab units; all were acquired through the 1964 Wabash Railroad merger. Dick Wallin photo/Warren Calloway collection.Expansion

Two other noteworthy components included the Norfolk & Petersburg (opened between its namesake cities in 1858) and the Virginia & Tennessee (completed between Lynchburg and Bristol, Virginia in 1856).

After recovering from damage caused during the "War Between The States" (the South's term for the Civil War) the N&P, V&T, and SRR merged in 1870 to form the 408-mile Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad. This short-lived company struggled during the financial Panic of 1873 and was forced into bankruptcy.

It was then reorganized as the Norfolk & Western Railroad during May of 1881. Another financial panic in 1893 thrust it into bankruptcy once more.

After a final reorganization the Norfolk & Western Railway was born on September 24, 1896. Prior to this last reorganization coal was already proving its most valuable commodity.

Logos

As Eric Grubb notes in his article, "Coal Supports The Norfolk & Western" from the November, 1947 issue of Trains Magazine, it all began in 1881 when vice-president of a young N&W, F.J. Kimball, firmly believed rich seams of bituminous were located in southwestern Virginia despite geologists proclaiming otherwise.

Kimball went on to discover the rich Pocahontas #3 seam and the railroad quickly pushed into the region.

According to Jim Cox’s book, “Rails Across Dixie: A History Of Passenger Trains In The American South,” the N&W took ownership of the unfinished New River Railroad and shipped out the first loads of coal from Pocahontas, Virginia on March 12, 1883.

The line, running via Bluefield, West Virginia and New River, Virginia officially opened a few months later on May 21st. Its first carloads totaled 54,500 tons that year but by 1887 had blossomed to roughly 1 million.

In the coming years this number steadily rose as the road expanded. Throughout the end of the 19th century the N&W continued extending its reach.

During 1896 it acquired the Lynchburg & Durham running between those two cities while the Roanoke & Southern allowed access to Winston-Salem via Roanoke.

This latter city became N&W’s headquarters and primary terminal. Its storied shops here went on to produce some of the finest steam locomotives ever built. In 1901 the N&W expanded to Cincinnati by purchasing the Cincinnati, Portsmouth & Virginia.

There were other important interchange points; two most noteworthy include Hagerstown, Maryland and Columbus, Ohio. The former offered connections with the Western Maryland, Pennsylvania and Baltimore & Ohio while the latter provided a link with the B&O, PRR, Chesapeake & Ohio and New York Central.

Norfolk & Western SD45 #1713 receives attention on March 4, 1977. Location not listed. Vincent Porreca photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Norfolk & Western SD45 #1713 receives attention on March 4, 1977. Location not listed. Vincent Porreca photo. American-Rails.com collection.At the turn of the 20th century the N&W's modern system, prior to postwar mergers, was essentially in place. At its peak size it consisted of just over 2,100 route miles, relatively small for a Class I carrier even then. Its total trackage, as of 1947, consisted of 4,543 miles.

It stretched from the tidewater port area of Norfolk/Portsmouth, Virginia to Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio, which covered a distance of 663 miles. While the N&W did move a variety of freight ranging from agriculture to merchandise, black diamonds were its mainstay.

While it is recognized for moving coal shipments predominantly eastbound from "Tipple to Tidewater" some of this traffic was also handled through its Midwestern gateway at Columbus.

According to Mike Schafer’s book, “Classic American Railroads – Volume III,” even during the early 1980s, just prior to the merger with the Southern, coal still comprised over 60% of its annual tonnage. It was so wealthy the company had paid an annual dividend since 1901 and continued to do so for decades.

Such prosperity was common through the 1920s but rare after the stock market crash in October of 1929. Many railroads struggled through the 1930s, but not the N&W.

A Norfolk & Western 2-6-6-2 (Z1-b) and 2-6-6-4 (A) at work in Norfolk, Virginia during 1956. Clarence Cade photo.

A Norfolk & Western 2-6-6-2 (Z1-b) and 2-6-6-4 (A) at work in Norfolk, Virginia during 1956. Clarence Cade photo.Electrification

When the N&W acquired the Virginian Railway in 1959 it inherited a road that was largely electrified west of Roanoke, Virginia. However, the Roanoke Road had operated its own section of energized territory for some time.

In 1913 the railroad embarked upon an electrification program to overcome the stiff grades on Elkhorn Mountain, west of Bluefield, West Virginia. Moving heavy freight over this stretch required the use of many 2-6-6-2 (Z-1) compound Mallets.

As Mr. Grubb's article notes the N&W worked with Westinghouse to implement the electrification, eventually opening 36.18 miles from Bluefield to Farm (near Vivian) in 1914. The system carried 11,000 volts at 25hz with substations located at Bluefield, Vivian, Maybeury, and North Fork.

Big boxcabs, classed as LC-1 (twelve units) and LC-2 (four additional units picked up in 1925) were tasked with moving the trains.

The primary power plant was situated at Bluestone, West Virginia. As coal demand spiked during World War I the system was extended 16.23 miles to Iaeger. Altogether, the main line here was energized across 52.41 miles.

There were also an additional 17 miles of coal branches electrified. After World War II the N&W carried out a nearly $12 million capital improvement program to eliminate the grades by constructing a 5-mile, double-tracked bypass. It opened on June 26, 1950 and the electrics were retired shortly thereafter.

System Map (1955)

The company's exemplary management wisely invested surplus income into the railroad's physical plant. Mr. Grubb notes that by the late 1940's, 72% of its network had been laid with heavy, 130-pound rail or greater.

In addition, key corridors were double-tracked, terminals were modernized, classification yards expanded, new steam designs developed, and by 1958 it boasted 46.7% of its network protected by Centralized Traffic Control (CTC).

The rest was guarded with automatic block signals according to Frank Shaffer's article, "Stuart Saunders And His Moneymaking Machine" from the February, 1963 issue of Trans Magazine.

"Precision Transportation" was not just a slogan, the company lived by this creed on a daily basis. During 1959 the N&W began the first of several takeovers by acquiring the nearby Virginian Railway.

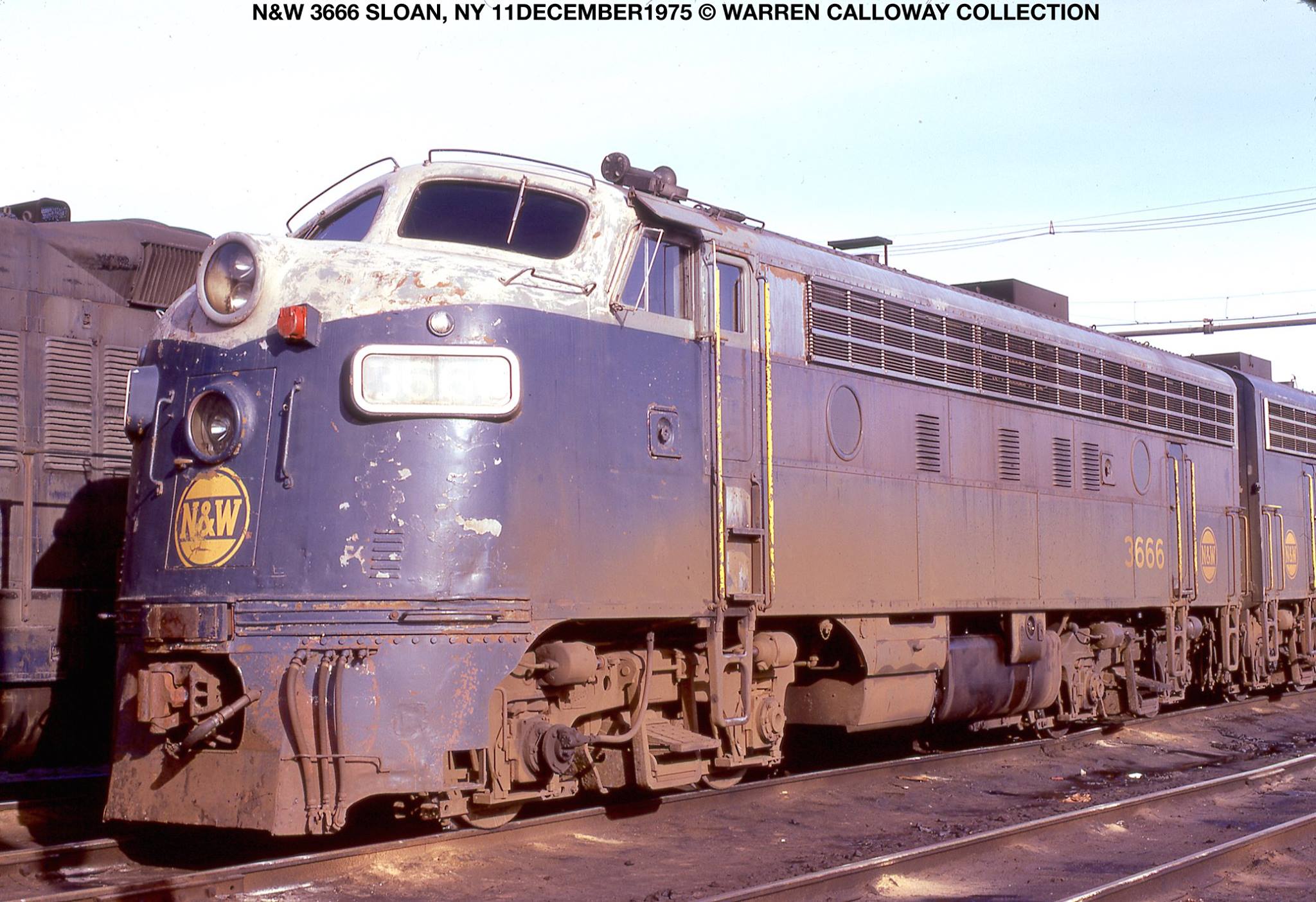

This pesky little road was equally wealthy and electrified west of Roanoke. It competed for the same coal that also shipped eastward to Norfolk. In the 1960s its portfolio grew three-fold when it picked up the small Atlantic & Danville (1962), much larger Nickel Plate Road (1964) and Wabash (1964). Finally, former interurban Illinois Terminal was added in 1981.

Norfolk & Western F7A #3666, a former Wabash unit (#1159-A), is seen here in Sloan, New York on December 11, 1975. Warren Calloway collection.

Norfolk & Western F7A #3666, a former Wabash unit (#1159-A), is seen here in Sloan, New York on December 11, 1975. Warren Calloway collection.O. Winston Link

Ogle Winston Link, more commonly known as O. Winston Link, was a famous professional photographer who eloquently captured the last days of steam on the Norfolk & Western. He began his career shortly after graduation from Polytechnic Institute in Brooklyn, New York.

Always carrying a great interest in railroads he captured his first night scene of N&W operations near Waynesboro, Virginia on January 21, 1955. Over the next few years, Link took hundreds of photos featuring N&W's last days of steam.

While an adept day photographer he became particularly famous for his dramatic night shots, which sometimes required hours of preparation and a single chance to get it right.

The trains, particularly the locomotives, were usually the focal point but not always. One of his most famous pieces was entitled "Hotshot Eastbound" as an A Class 2-6-6-4 speeds behind a drive-in theater in Iaeger, West Virginia as folks enjoy the picture.

This was typical of Link's work which often invoked the human element alongside these great machines of commerce.

Over the years there have been many books showcasing his photography. Link passed away on January 30, 2001. Today, you can also see his work at the O. Winston Link Museum in Roanoke, Virginia.

Steam Fleet

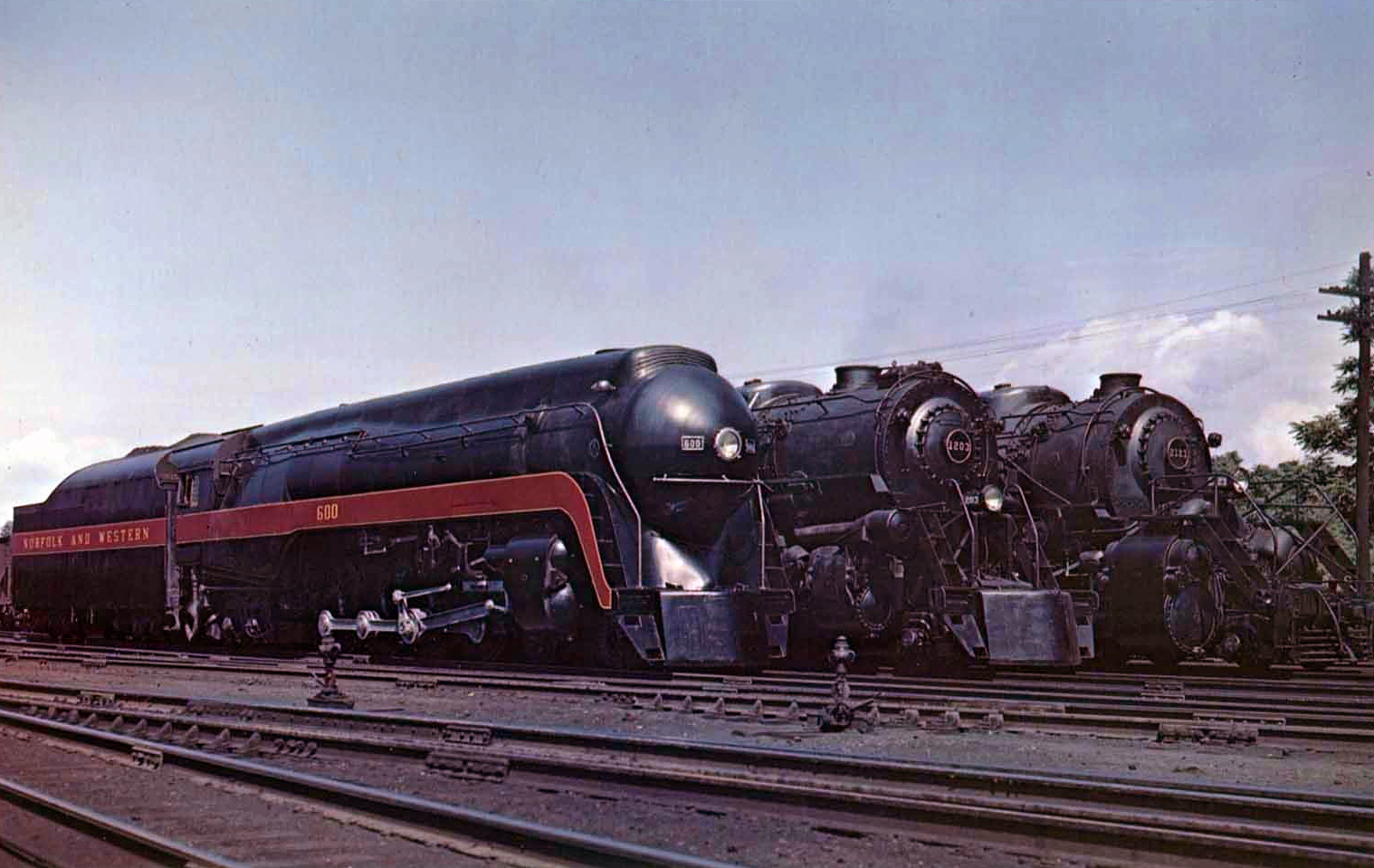

Within the industry and among historians the N&W is widely recognized for its use of steam power. The company was arguably better at designing and building the locomotives than even noted manufacturers like Baldwin and the American Locomotive Company (Alco).

The fabled Roanoke Shops rolled out hundreds over the years with such classic designs as the 4-8-4 "J," 2-6-6-4 "A," and 2-8-8-2 "Y."

The railroad was relentless in its pursuit of power and efficiency, doing whatever it could to squeeze out further improvements. In the postwar years the Shops were still rolling out new units even as many counterparts retired theirs in favor of diesels.

As the company perfected the technology new maintenance facilities were constructed to quickly overhaul locomotives (notorious for their maintenance-intensive nature).

One of the most interesting was the "Lubritorium." Unique to the N&W these small structures swiftly serviced steamers for their next assignment. The railroad became so adept at the practice motive power could be turned and ready to go within an hour!

After holding out well into the 1950s, master steam builder Norfolk & Western finally broke down and began ordering large batches of road-switchers from Electro-Motive and the American Locomotive Company beginning in 1955. In this publicity photo GP9 #502 (built as #764 in 1957) sits in Roanoke, Virginia during March of 1959.

After holding out well into the 1950s, master steam builder Norfolk & Western finally broke down and began ordering large batches of road-switchers from Electro-Motive and the American Locomotive Company beginning in 1955. In this publicity photo GP9 #502 (built as #764 in 1957) sits in Roanoke, Virginia during March of 1959.Steam remained in regular service until the mid-1950s, which signaled its technological peak. No other system operated such advanced designs as the Roanoke Road. Its locomotives carried such features as roller-bearings on all axles, high capacity boilers, superheaters, and automatic lubricators.

The big 2-8-8-2 compounds (Y's) handled the heavy drag assignments, muscling over the mountainous territory on the Pocahontas Division while 2-6-6-4's (A's) could speed time freights up to 70 mph on gentler grades. These latter units could also work duel assignments in passenger service.

Finally, the powerful 4-8-4's (J) and their smaller counterparts, 4-8-2's (K), generally handled the passenger trains although these locomotives could handle freight work as well.

The N&W reluctantly began purchasing diesels in 1955 when the first GP9's arrived on the property (ironically, that same year the company unveiled its last new steamers when it outshopped a batch of 0-8-0 switchers).

Despite president Robert H. Smith's love for the steamer and belief in the motive power it simply could not compete against the diesel's operational efficiency. In addition, rising labor costs factored in as did the difficulty in locating components and spare parts.

Photographing the photographer who is preparing to document recently completed Norfolk & Western 2-8-8-2 #2171 (Y-6b) circa 1948. These were the last of N&W's big compounds, products of the Roanoke Shops, and are regarded as the best in the series.

Photographing the photographer who is preparing to document recently completed Norfolk & Western 2-8-8-2 #2171 (Y-6b) circa 1948. These were the last of N&W's big compounds, products of the Roanoke Shops, and are regarded as the best in the series.Final Years

Stuart Saunders, who replaced Smith in 1958, saw no use for the steam locomotive as Rush Loving, Jr. notes in his book, "The Men Who Loved Trains."

Among his other initiatives he quickly purchased diesels and had completed the switch within a few years. The N&W's late era steam fleet was memorialized and captured on film prior to its retirement by renowned photographer O. Winston Link.

There have been many excellent and famous photographers throughout the years although Mr. Link is perhaps the most celebrated due to his subject matter and exquisite work.

In addition to the mergers mentioned above, the N&W added the Delaware & Hudson and Erie Lackawanna on July 1, 1968 as part of an agreement which included them under the company name Dereco, Inc.

Norfolk & Western E8A #3815 and a Geep at WABIC Tower in Decatur, Illinois; May, 1966. The WaBash and Illinois Central crossed at this location. Rick Burn photo.

Norfolk & Western E8A #3815 and a Geep at WABIC Tower in Decatur, Illinois; May, 1966. The WaBash and Illinois Central crossed at this location. Rick Burn photo.Passenger Trains

After a quick look at the N&W’s balance sheets it is clear the railroad never derived a large percentage of its revenue from passenger service which made up less than 3% of its total in the postwar period according to David P. Morgan's article, "Fine New Feathers" from the February, 1950 issue of Trains Magazine.

However, the road operated a fine assortment of long-distance trains spearheaded by the Powhatan Arrow and Pocahontas.

These trains, adorned in a beautiful maroon and gold livery, were pulled by the famously streamlined 4-8-4, J Class locomotives. The N&W also participated in through movements with the Southern Railway.

Birmingham Special: Operated between New York and Birmingham, Alabama in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad and Southern Railway with the N&W carrying it between Lynchburg and Bristol.

Cannon Ball: Operated between Norfolk and New York in conjunction with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac with the N&W carrying it between Norfolk and Petersburg.

Cavalier: (Norfolk - Cincinnati)

Pelican: Operated between New York and New Orleans in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad and Southern Railway with the N&W carrying it between Lynchburg and Bristol.

Pocahontas: (Norfolk - Cincinnati/Columbus)

Powhatan Arrow: (Norfolk - Cincinnati)

Tennessean: Operated between New York and Memphis in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad and Southern Railway with the N&W carrying it between Lynchburg and Bristol.

The paper company was entirely a protective nature carried out by Roanoke to protect itself from the EL's fragile financial state. In a related corporate move the N&W had recently gained its independence when the Pennsylvania Railroad was forced to divest its holdings due to the impending merger with New York Central.

Try as it might the EL, headed by N&W management, could not overcome its problems ranging from debt to a crumbling situation in the Northeast as Penn Central fell apart.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| T6 | 10-49 | 1959 | 40 |

| RS3 | 300-307 | 1955-1956 | 8 |

| RS11 | 308-406 | 1956-1961 | 99 |

| RS36 | 407-412 | 1962 | 6 |

| C420 | 413-420 | 1964 | 8 |

| C425 | 1000-1017 | 1964-1965 | 18 |

| C628 | 1100-1129 | 1965-1966 | 30 |

| C630 | 1130-1139 | 1966-1967 | 10 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP9 | 10-13, 506-521, 620-699, 714-914 | 1955-1959 | 301 |

| GP35 | 200-239, 1300-1328 | 1963-1965 | 69 |

| GP30 | 522-565 | 1962 | 44 |

| GP18 | 915-962 | 1960-1961 | 48 |

| GP40 | 1329-1388 | 1966-1967 | 60 |

| SD35 | 1500-1579 | 1965 | 80 |

| SD40 | 1580-1624 | 1966-1971 | 45 |

| SD40-2 | 1625-1652, 6073-6207 | 1973-1980 | 163 |

| SD45 | 1700-1814 | 1966-1970 | 115 |

| GP38AC | 4100-4159 | 1971 | 60 |

| SD50S | 6500-6505 | 1980 | 6 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U28B | 1900-1929 | 1966 | 30 |

| U30B | 1930-1965, 8465-8539 | 1965 | 111 |

| U25B | 3515 | 1965 | 1 |

| C30-7 | 8003-8082 | 1978-1979 | 80 |

| U30C | 8300-8302 | 1974 | 3 |

| C36-7 | 8500-8530 | 1981-1982 | 31 |

Steam Roster

Few other railroads developed steam technology to the extent of the Norfolk & Western Railway. At the turn of the 20th century the system primarily relied on 2-8-0s for general freight service.

Although Consolidations remained a staple of the N&W's fleet, in the modern steam era the railroad primarily relied on large 2-8-8-2s and 2-6-6-4s for freight operations while 4-6-2s and 4-8-4s generally handled passenger assignments.

In many cases, the Roanoke Shops directly produced new steam locomotives, especially after 1930 with modern technologies such as Timken roller bearings, automatic lubricators, and automatic stokers.

During the 1940s the N&W developed what it called the "Lubritorium," a modern, brightly lit engine facility which could fully service a steam locomotive in just 90 minutes or less. These facilities were located at Shaffers Crossing (Roanoke), Bluefield, Williamson, Portsmouth, and Pulaski.

The N&W was a pioneering force in locomotive technology, especially steam. It engineered some of the most advanced steam locomotives, including the renowned J-class and Y-class, which exemplified power and efficiency.

These iron horses became the backbone of its freight operations, hauling staggering volumes of coal with a distinctive efficiency that the N&W was celebrated for.

World War II bolstered the N&W's significance, as coal demand surged, cementing its status as a logistical powerhouse. Despite the national trend towards dieselization in the post-war years, the N&W held out, committing to steam well into the 1950s, epitomized by their slogan "Precision Transportation." Modernization eventually necessitated change, and by 1960, the N&W completed its shift to diesel.

The pride of Roanoke; Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #600 (J), 2-6-6-4 #1203 (A), and compound 2-8-8-2 #2133 (Y-6) pose together at Shaffer's Crossing, Virginia (Roanoke) in 1945.

The pride of Roanoke; Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #600 (J), 2-6-6-4 #1203 (A), and compound 2-8-8-2 #2133 (Y-6) pose together at Shaffer's Crossing, Virginia (Roanoke) in 1945.Switchers

| Wheel Arrangement | Class | Road Number(s) | Quantity | Builder(s) | Completion Date | Retirement Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-8-0 | S1 | 255-284 | 30 | Baldwin | 1948 | 1958-1960 | ex-Chesapeake & Ohio #255-284. |

| 0-8-0 | S1a | 200-244 | 45 | N&W | 1951-1953 | 1958-1960 | - |

Passenger Locomotives

| Wheel Arrangement | Class | Road Number(s) | Quantity | Builder(s) | Completion Date | Retirement Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-8-2 | K2 | 116-125 | 10 | Brooks (Alco) | 1919 | 1957-1959 | - |

| 4-8-2 | K2a | 126-137 | 12 | Baldwin | 1923 | 1958-1959 | - |

| 4-8-2 | K3 | 200-209 | 10 | N&W | 1926 | Sold (1944-1945) | - |

| 4-4-2 | J | 600-606 | 7 | Baldwin | 1903-1904 | 1931-1935 | - |

| 4-6-0 | V | 950-961 | 12 | Baldwin | 1900 | 1929-1948 | - |

| 4-6-0 | V-1 | 962-966 | 5 | Richmond (Alco) | 1902 | 1929-1933 | - |

| 4-6-0 | A | 86-90 | 5 | Baldwin | 1902-1904 | 1928 | - |

| 4-6-2 | EE | 595-599 | 5 | Richmond (Alco) | 1905 | 1934-1939 | - |

| 4-6-2 | E1 | 580-594 | 15 | Baldwin | 1907 | 1931-1938 | - |

| 4-6-2 | E2 | 564-579 | 16 | Richmond (Alco) | 1910 | 1938-1958 | - |

| 4-6-2 | E2a | 553-563 | 10 | Baldwin | 1912 | 1940-1958 | - |

| 4-6-2 | E2b | 543-552 | 10 | N&W | 1913-1914 | 1938-1955 | - |

| 4-6-2 | E3 | 500-504 | 5 | Baldwin | 1913 | 1946-1947 | ex-PRR Class K3s |

| 4-8-4 | J | 600-604 | 5 | N&W | 1941-1942 | 1958-1959 | Streamlined |

| 4-8-4 | J-1 | 605-610 | 6 | N&W | 1943 | 1959 | Streamlined in 1945-1947, reclassed as J. |

| 4-8-4 | J | 611-613 | 3 | N&W | 1950 | 1959 | Streamlined |

| 4-8-2 | K1 | 1000-1015 | 16 | N&W | 1916-1917 | 1957-1958 | - |

Class J (4-8-4)

Freight Locomotives

| Wheel Arrangement | Class | Road Number(s) | Quantity | Builder(s) | Completion Date | Retirement Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-8-0 | W | 800-829 | 30 | Baldwin | 1898-1899 | 1926-1934 | Rebuilt as Class W-1. |

| 2-8-0 | W1 | 830-842, 844-865 | 34 | N&W, Baldwin, Richmond (Alco) | 1900-1901 | 1926-1934 | 5 were rebuilt to 0-8-0T. |

| 2-8-0 | W2 | 673-799 | 212 | N&W, Baldwin | 1901-1905 | 1926-1952 | - |

| 2-8-0 | B | 61-70 | 10 | Baldwin | 1898-1904 | 1933-1934 | Cross-compound designs; they were later simpled between 1909-1912. |

| 4-8-0 | M | 375-499 | 125 | Richmond (Alco), BLW | 1906-1907 | 1926-1958 | - |

| 4-8-0 | M1 | 1000-1099 | 100 | Richmond (Alco), BLW | 1907 | 1926-1947 | - |

| 4-8-0 | M2 | 1100-1149 | 50 | Baldwin | 1910 | 1950-1957 | - |

| 4-8-0 | M2a | 1150-1152 | 3 | N&W | 1911 | 1950-1956 | - |

| 4-8-0 | M2b | 1153-1154 | 2 | N&W | 1911 | 1950-1956 | - |

| 4-8-0 | M2c | 1155-1160 | 6 | N&W | 1911-1912 | 1952-1957 | - |

Class K (4-8-2)

Articulated Designs

| Wheel Arrangement | Class | Road Number(s) | Quantity | Builder(s) | Completion Date | Retirement Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-8-8-0 | X1 | 990-994 | 5 | Schenectady (Alco) | 1910 | 1934 | - |

| 2-6-6-2 | Z1 | 1300-1314 | 15 | Richmond (Alco) | 1912 | 1934 | - |

| 2-6-6-2 | Z1a | 1315-1489 | 175 | Richmond (Alco), Baldwin | 1912-1918 | 1934-1958 | 1331-1489 were rebuilt as Class Z1b. |

| 2-6-6-2 | Z2 | 1399 | 1 | Richmond (Alco) | 1928 | 1958 | Rebuilt from Class Z1a. |

| 2-6-6-4 | A | 1200-1209 | 10 | N&W | 1936-1937 | 1958-1959 | - |

| 2-6-6-4 | A | 1210-1224 | 15 | N&W | 1943 | 1959-1961 | - |

| 2-6-6-4 | A | 1225-1234 | 10 | N&W | 1944 | 1958-1959 | - |

| 2-6-6-4 | A | 1235-1242 | 8 | N&W | 1949-1950 | 1958-1959 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y2 | 995-999 | 5 | Baldwin | 1910 | 1924 | All examples were rebuilt and classed as Y2a. |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y2 | 1700-1704 | 5 | N&W | 1918-1921 | 1946-1951 | All examples were rebuilt and classed as Y2a. |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y2a | 1705-1710 | 6 | N&W | 1924 | 1948-1949 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y2 | 1711-1730 | 20 | Baldwin | 1919 | 1948-1951 | All examples were rebuilt and classed as Y2a. |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y3 | 2000-2044 | 45 | Schenectady (Alco) | 1919 | 1957-1958 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y3 | 2045-2049 | 5 | Baldwin | 1919 | 1957-1958 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y3a | 2050-2079 | 30 | Richmond (Alco) | 1923 | 1958-1959 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y3b | 2080-2089 | 10 | Richmond (Alco) | 1927 | 1958 | Reclassed as Y4. |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y4 | 2090-2109 | 20 | N&W | 1930-1932 | 1958-1960 | Reclassed as Y5. |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y5 | 2120-2154 | 35 | N&W | 1936-1940 | 1958-1960 | |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y6a | 2155-2170 | 16 | N&W | 1942 | 1958-1960 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y6b | 2171-2187 | 17 | N&W | 1948-1949 | 1959-1960 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y6b | 2188-2194 | 7 | N&W | 1950-1951 | 1959-1960 | - |

| 2-8-8-2 | Y6b | 2195-2200 | 6 | N&W | 1951-1952 | 1959-1960 | - |

Class A (2-6-6-4)

Class Z (2-6-6-2)

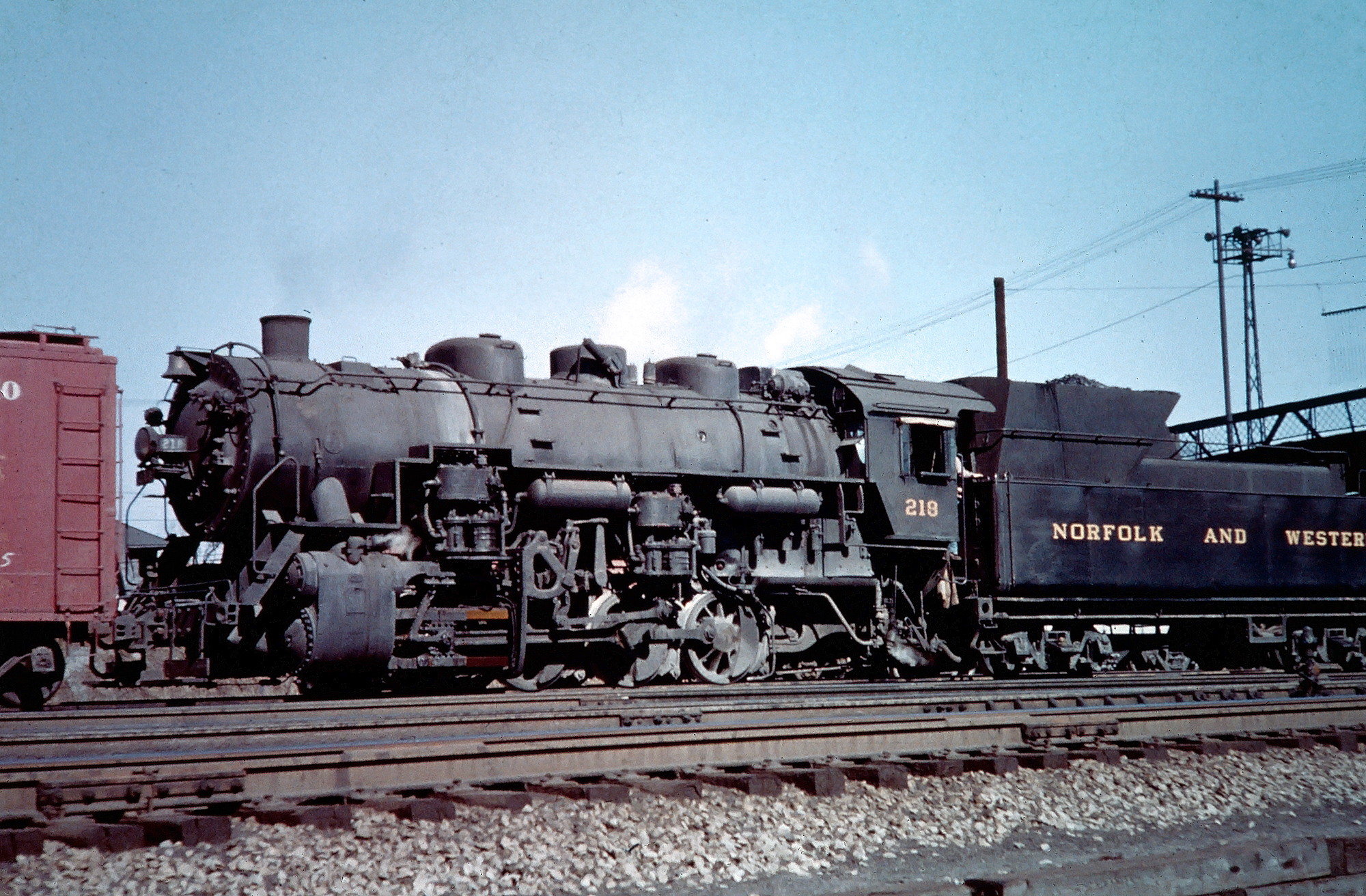

One of the Norfolk & Western's big 0-8-0 switchers, #218, is seen here at work in Roanoke, Virginia, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

One of the Norfolk & Western's big 0-8-0 switchers, #218, is seen here at work in Roanoke, Virginia, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Norfolk Southern

After Hurricane Agnes dealt heavy flooding to the region and forced EL into bankruptcy N&W sold off its interests in the railroad. For the Norfolk & Western its end began in 1980 when merger proceedings began with the nearby Southern Railway.

They had been taken aback by the new CSX Corporation (of which the railroad arm became CSX Transportation) formed that year between Chessie System, Seaboard Coast Line, and several smaller carriers. Now dwarfed by the new conglomerate the two carriers realized their best chance for survival was through merger.

The union was approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1982. The newly created Norfolk Southern Corporation today carries on the fine traditions set forth by its predecessors. The company is still renowned for its sound management and business practices.

It continually ranks at the top of the industry in annual revenue and a low operating ratio. During the 1990s another fight broke out between NS and CSX, this time for control of Conrail. In the end the two agreed to split Big Blue with NS gaining a 58% stake in the company.

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:57 PM

The Wisconsin Great Northern Railroad will once again welcome passengers aboard its popular Spring BBQ Dinner Train in 2026. -

Connecticut DOT Awards $20 Million In Railroad Grants

Mar 12, 26 01:19 PM

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) has announced a new round of funding aimed at improving the safety, reliability, and capacity of the state’s freight rail network. -

California's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 12:59 PM

While the Niles Canyon Railway is known for family-friendly weekend excursions and seasonal classics, one of its most popular grown-up offerings is Beer on the Rails. -

Reading & Northern Unveils Semiquincentennial 1776

Mar 12, 26 12:48 PM

In November 2025, the Reading, Blue Mountain & Northern Railroad (RBMN)—commonly known as the Reading & Northern—announced the debut of a striking patriotic locomotive commemorating the upcoming 250th… -

New Jersey's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:35 AM

On select dates, the Woodstown Central Railroad pairs its scenery with one of South Jersey’s most enjoyable grown-up itineraries: the Brew to Brew Train. -

Florida BBQ Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 11:28 AM

While Florida does not currently offer any BBQ train rides the Florida Railroad Museum does host a similar event, a campfire experience! -

Texas "Murder Mystery" Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:40 AM

Here’s a comprehensive look into the world of murder mystery dinner trains in Texas. -

Connecticut's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:36 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains. -

Missouri's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:33 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 12, 26 10:28 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Charlotte Approves $37.9M For "Red Line" To Lake Norman

Mar 11, 26 02:18 PM

The Charlotte City Council has approved $37.9 million in funding for the next phase of design work on the long-planned Red Line commuter rail project. -

NS, Progress Rail Announce SD70ICC Modernization

Mar 11, 26 12:15 PM

Norfolk Southern Railway has announced a significant locomotive modernization initiative in partnership with Progress Rail Services Corporation that will rebuild 96 existing road locomotives into a ne… -

Colorado Seeks Input On Proposed Front Range Passenger Train Name

Mar 11, 26 11:55 AM

Colorado officials are inviting the public to help name a proposed passenger train that could one day connect major cities along the state’s heavily traveled Interstate 25 corridor. -

Virginia Whiskey Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 11:22 AM

Among the Virginia Scenic Railway's most popular specialty excursions is the “Bourbon & BBQ” tasting train, an adults-oriented rail journey that pairs scenic views of the Shenandoah Valley with guided… -

Minnesota's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:32 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train. -

New Mexico's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:23 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Indiana's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:19 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:02 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Kentucky Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 11:39 AM

The Bluegrass State is home to beautiful rolling farms and the western Appalachian Mountain chain, which comes alive each spring. A few railroad museums host Easter-themed events during this time. -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:26 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

NS Faces Multiple Derailments Near Historic Horseshoe Curve

Mar 10, 26 10:15 AM

One of America’s most famous railroad landmarks, the legendary Horseshoe Curve west of Altoona, Pennsylvania, has recently been the site of multiple freight-train derailments involving Norfolk Souther… -

Oregon's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:11 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:57 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Connecticut's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:54 AM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on… -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:37 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Union Pacific Restores Rail Bridge Service in Lincoln

Mar 09, 26 11:34 PM

Union Pacific crews have successfully restored freight rail service across a key bridge in Lincoln, Nebraska, completing a rapid reconstruction effort in just a few weeks. -

TVRM To Assist In Gas-Powered Locomotive's Restoration

Mar 09, 26 11:15 PM

The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum has announced it is assisting in the eventual cosmetic restoration of a former gas powered locomotive used in the logging industry. -

Michigan's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:37 AM

Spring sometimes comes late to Michigan but this doesn't stop a handful of the state's heritage railroads from hosting Easter-themed rides. -

Pennsylvania's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:05 AM

Pennsylvania is home to many tourist trains and several host Easter-themed train rides. Learn more about these special events here. -

Tennessee's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:33 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Michigan's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:07 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:56 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Maryland Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:37 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

New York's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:16 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:15 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Colorado Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:14 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:13 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 1356 Receives Cosmetic Restoration

Mar 07, 26 02:19 PM

A significant preservation effort is underway in Missoula, Montana, where volunteers and local preservationists have begun a cosmetic restoration of Northern Pacific Railway steam locomotive No. 1356. -

New York's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 02:08 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Kentucky's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:17 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Ohio's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:15 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

Georgia 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides In Cordele

Mar 07, 26 10:13 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel… -

Arizona Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:12 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Massachusetts's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 09:00 AM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:57 AM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

Indiana's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:55 AM

Among IRE’s most talked-about offerings is the Wine & Whiskey Train—an adults-only, evening-style trip that leans into the best parts of classic rail travel: atmosphere, comfort, and a little cele… -

North Carolina's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:53 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Arkansas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:50 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

California Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:49 AM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Construction Continues On Railroad Museum Of Pennsylvania Roundhouse

Mar 05, 26 01:52 PM

Construction is underway on a long-anticipated roundhouse exhibit building at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, a project designed to preserve several of the most historically signific…