Staten Island Rapid Transit

Published: January 6, 2026

By: Adam Burns

New York City’s rail-transit story is usually told through Manhattan subways, Brooklyn elevated lines, and the great commuter railroads that feed Grand Central and Penn Station. Yet across the harbor sits a system with a lineage every bit as old—and in some ways more unusual—than much of the subway: the Staten Island Rapid Transit (SIRT), today publicly branded as the Staten Island Railway (SIR).

It’s a rapid-transit operation with a railroad ancestry, once tied to a major trunk carrier (the Baltimore & Ohio), shaped by grand but unrealized ambitions (a Narrows tunnel to Brooklyn), and defined by a recurring theme in American transit history: service is rarely just about technology—it’s about politics, geography, money, and the changing patterns of where people live and work.

What follows is a detailed look at how Staten Island’s railway came to be, how it evolved from steam-era local railroad into an electrified rapid-transit line, how it lost two-thirds of its passenger network in a single day, and how it persisted into the modern MTA era—while also playing an underappreciated role in freight revival on the island.

A Staten Island Rapid Transit train at Great Kills, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.

A Staten Island Rapid Transit train at Great Kills, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.Beginnings: Staten Island’s Rail Dream Takes Shape (1850s–1870s)

Staten Island’s geography made it both close to New York City and oddly separate from it. The island’s shoreline offered natural ferry landings, while its interior and south shore were increasingly attractive for settlement—if transportation could keep pace. Early attempts to build a rail line on Staten Island date to the mid-19th century, culminating in a route that reached Tottenville by 1860—establishing the island’s first continuous north–south rail corridor.

Over time, control and corporate structure changed as financiers and operators reorganized the property into new companies, a common pattern in 19th-century American railroading. By the 1870s, the line had been reorganized again, reflecting both the financial instability and the still-emerging market for island-wide rail service.

But the truly transformative chapter—what made Staten Island’s line distinct from many other local railroads—arrived with a development-minded vision: a coordinated transportation hub tied to New York Harbor commerce, and an integrated system of passenger and freight connectivity.

The Rapid Transit Era: Expansion, Ambition, and the Birth of “SIRT” (1880s–1899)

In 1880, the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company was organized amid a push to develop the island and knit rail service into a broader harbor transportation network. The “Rapid Transit” label was more than marketing: the goal was frequent, reliable service linking neighborhoods to the St. George ferry terminal, where passengers could continue to Manhattan.

This period also saw the growth of a branching network. In addition to the main north–south route (eventually the line to Tottenville), Staten Island gained additional passenger corridors:

- North Shore Branch (west and north waterfront communities)

- South Beach Branch (east shore communities)

These branches opened in the late 1880s and turned the system into something more akin to a small metropolitan rail network than a single local line.

The North Shore line, for example, is documented as beginning construction in the 1880s and offering service that tied several waterfront communities into St. George. The South Beach Branch similarly created a second passenger spine on the island’s east side.

By the end of the 19th century, these operations consolidated into the corporate identity most people associate with the early system: the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway Company—SIRT—which would become closely linked with a major mainland railroad.

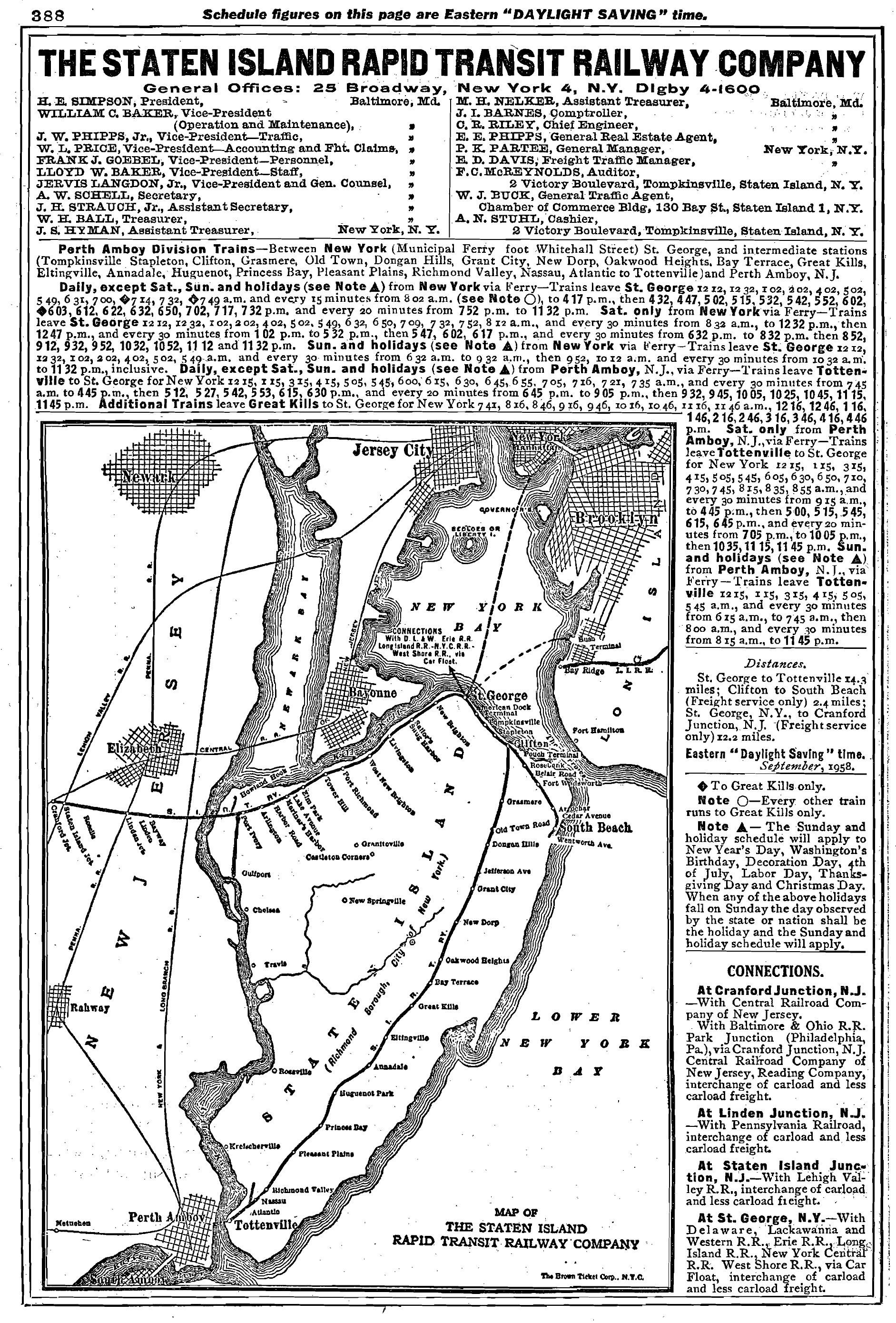

System Map (1958)

The Baltimore & Ohio Years: A Trunk Railroad on an Island (1899–1971)

From 1899 until 1971, the Staten Island Rapid Transit was operated as a subsidiary of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O)—a startling fact if you’re used to thinking of the B&O in terms of the National Limited, the Capitol Limited, and coal trains threading Appalachia. Staten Island was a geographically isolated “appendix,” but the B&O’s interest wasn’t sentimental: it was strategic.

A major railroad saw value in Staten Island as a potential freight gateway—especially if it could secure reliable harbor crossings and connections to other rail networks. Over time, SIRT developed as a hybrid: a line that carried daily commuters and shoppers, but also served industries and yards, and remained embedded in the logic of railroad—not subway—operation.

This dual identity shaped everything that came next: electrification decisions, terminal design, rolling stock choices, and the constant tension between local passenger service (often money-losing) and freight operations (sometimes more promising, but dependent on wider economic forces).

Electrification and a “Subway That Might Have Been” (1920s)

One of the defining moments in Staten Island Rapid Transit history came not from the island itself, but from a broader policy movement: New York’s push to eliminate steam railroading within city limits. The Kaufman Act, signed in 1923, mandated electrification of rail operations within New York City by a deadline in the mid-1920s.

SIRT’s electrification was completed largely by the end of 1925, using 600 volt DC third rail, a choice that aligned with the city’s rapid-transit standards and anticipated a future that—at the time—seemed plausible: a direct rail tunnel under the Narrows to Brooklyn, linking Staten Island trains into the broader subway network.

That Narrows tunnel concept has echoed through New York planning debates for a century, but in the 1920s it was not merely a fantasy. Electrification “to subway compatibility” made sense only if a physical connection might be built. The dream: Staten Island trains running into Brooklyn’s BMT lines, creating a one-seat ride that would radically reshape the island’s development trajectory.

Electrification did deliver real improvements immediately:

- Faster acceleration and more frequent service potential

- A more “rapid transit” feel than the earlier steam and coach era

- A modernization of operations that suited commuter patterns to St. George

But the deeper significance was this: by electrifying to third-rail rapid-transit standards, SIRT became a rare example of a railroad-owned operation evolving toward subway-like identity—without ever fully joining the subway.

Three Branches, One Island Network: How the System Once Worked

For a brief mid-20th-century moment, Staten Island had something like a complete rapid-transit grid for its population patterns:

- Main Line (St. George–Tottenville) – the north–south backbone (and today’s surviving passenger route).

- North Shore Branch – serving the island’s north and west waterfront communities.

- South Beach Branch – serving east-shore communities from the Clifton area toward South Beach.

St. George terminal was the essential hinge—one of the country’s notable “boat-train” interchanges, where ferry and rail coordinated passenger movement. Modern descriptions still emphasize the terminal’s multi-track layout and the system’s role as Staten Island’s only rapid-transit line.

This three-branch structure matters because it reframes what was lost later: Staten Island didn’t simply “never get transit.” It had a real network—and then, in a single stroke, most of it vanished.

Crisis and Contraction: 1953 and the End of Two Branches

Postwar New York changed fast. Automobiles reshaped shopping and commuting, while bus networks expanded and competed directly with rail service. Staten Island was not immune; in fact, the island’s lower densities and dispersed development made it especially vulnerable to a shift toward road-based transit.

On March 31, 1953, passenger service on both the North Shore Branch and the South Beach Branch ended. The closure was a watershed moment. It reduced Staten Island’s passenger rail network from a branching system to essentially one surviving corridor: the St. George–Tottenville line. Freight lingered on portions of the North Shore line for decades longer, but the passenger-facing identity of a three-branch rapid-transit network was gone.

A key lesson here—one that resonates with transit histories nationwide—is that “ridership” is rarely just a matter of whether people like trains. It’s shaped by comparative price, service patterns, and the political choice of what to subsidize. By the early 1950s, the rail branches were competing with buses and a changing Staten Island commuting culture; the result was a strategic retreat.

And yet, the surviving Tottenville line endured—partly because it served the strongest continuous corridor of Staten Island communities, and partly because St. George remained a crucial ferry interface.

From Private Railroad to Public Transit: The MTA Takes Over (1968–1971)

The late 1960s brought a new turning point. With private railroad economics increasingly unfavorable for local passenger service, public control became the logical outcome. Plans and negotiations culminated in a transfer in which New York City purchased the line for $1 and the MTA paid the B&O for equipment, while freight rights and responsibilities were carefully structured around continued operations.

The Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority (SIRTOA) was incorporated in 1970 and took over passenger operation in 1971 when the line was acquired.

This moment matters because it formally shifted Staten Island’s rail line from a railroad subsidiary to a transit authority operation—while still retaining railroad characteristics and freight entanglements. Unlike many subway lines, the Staten Island Railway’s modern governance and infrastructure were shaped by the terms of a railroad-to-public transfer, including requirements around grade crossings and track condition related to freight.

In other words: Staten Island’s rapid transit didn’t “grow up” inside the subway—it was adopted into the transit family after a long life as a railroad property.

A SIRT train between Richmond Valley and Nassau, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.

A SIRT train between Richmond Valley and Nassau, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.Modern Identity: Rebranding, Fare Policy, and System Upgrades (1990s–2000s)

By the early 1990s, the line’s identity continued to evolve inside the MTA structure. Operational changes, repair projects, and modernization efforts reshaped both rider experience and the system’s public image. Historical summaries note major track replacement projects through the 1990s and organizational transfers within New York City Transit/MTA structures.

A highly visible milestone came in 1994, when the MTA rebranded the Staten Island Rapid Transit as the MTA Staten Island Railway (SIR)—a return to an earlier name and a clearer public-facing identity.

Fare policy also became central to the line’s modern story. Over time, Staten Island Railway service became closely integrated with the citywide fare system—especially at the St. George interface—reinforcing the idea that the line is part of New York’s rapid-transit ecosystem even if it remains physically separate from the subway.

The Freight Story: Decline, the Arthur Kill Bridge, and Reactivation

Many casual riders think of the Staten Island Railway purely as a passenger line. But freight has been a persistent undercurrent—sometimes dormant, sometimes central.

The Arthur Kill crossing is the critical infrastructure piece. The Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge (opened in 1959, replacing an older swing bridge) provided a direct rail link between Staten Island and New Jersey.

Over decades, manufacturing shifts and a broader move toward trucking reduced rail freight volumes, and the connection eventually fell into disuse—freight service via the bridge ended around 1990, with the line effectively closed for years.

Then came the 2000s freight revival. A major rehabilitation project—often described at roughly $72 million—involved repairing the bridge and restoring the Staten Island rail freight connection, with the goal of improving port/intermodal capability and reducing truck traffic.

Regular service is documented as resuming in April 2007, tied to municipal solid waste movements and intermodal/container activity linked to Howland Hook and related facilities.

This freight dimension is more than a side plot: it illustrates why Staten Island’s rail corridor has remained valuable even when passenger expansion stalled. In a dense metro region where truck congestion and port logistics carry major economic and environmental costs, the rail link across the Arthur Kill became a tool for policy goals beyond transit ridership—namely, freight diversion and industrial access.

The North Shore Question: A Branch That Won’t Quite Die

Even after 1953, Staten Island’s “lost” passenger branches never fully disappeared from public imagination. The North Shore Branch is the clearest example—partly because its corridor still threads through communities that have periodically sought better transit access.

Notably, a small section of the line was briefly used for a ballpark-oriented passenger extension in the 2000s, illustrating how the right-of-way continues to invite reuse.

While broader restoration proposals have appeared in studies and political discussion, the persistent pattern has been this: Staten Island’s growth and travel needs keep generating interest, but the cost and complexity of building a true rapid-transit expansion remain formidable.

The larger implication is that SIRT/SIR is both a “finished” system—one surviving passenger trunk line—and an “unfinished” one, haunted by the alternate histories in which the Narrows tunnel is built, or the North Shore corridor returns as a modern rapid-transit or light-rail route.

Rolling Stock and the Rider Experience: A Subway Feel, Railroad DNA

SIRT/SIR’s passenger operations look and feel like rapid transit—third rail, multiple-unit trains, station spacing suited to neighborhood travel—yet the line’s railroad DNA shows up in subtle ways: the way it interfaces with ferry service at St. George, the presence of yards and shops tied to a legacy railroad corridor, and the long history of freight rights and shared infrastructure.

Enthusiast and historical documentation emphasizes that the line was operated by the B&O as a subsidiary for much of its life, and that St. George remains one of the most notable ferry-rail interfaces in the United States.

This “in-between” identity is why Staten Island Railway fascinates transit historians: it’s a rapid-transit line that never fully merged into the subway, and a railroad property that evolved into a transit utility without losing its freight-linked structure.

A Brief Timeline of Key Dates

- 1860: Line completed to Tottenville (early core of today’s main line).

- 1880: Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company organized (rapid-transit era begins).

- 1886–1888: Branch-era growth (North Shore and South Beach corridors enter service in the late 1880s).

- 1923–1925: Kaufman Act era; electrification completed with third rail compatible with subway standards.

- March 31, 1953: Passenger service ends on North Shore and South Beach branches.

- 1971: MTA-era begins; SIRTOA takes over passenger operations after city acquisition.

- 1994: Rebranding as MTA Staten Island Railway (SIR).

- 2007: Freight service resumes across the Arthur Kill link (post-rehabilitation).

Staten Island Rapid Transit S2 #9031 (built as #487) works freight service at Bay Terrace, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.

Staten Island Rapid Transit S2 #9031 (built as #487) works freight service at Bay Terrace, New York in August, 1964. Rick Burn photo.Conclusion

The Staten Island Rapid Transit system is easy to overlook because it is physically separated from the subway map’s dense web. Yet its story is a concentrated version of New York’s broader transportation history: private railroad ambitions giving way to public transit realities; modernization driven by regulation and city planning; service contraction shaped by buses and automobiles; and a persistent tension between passenger needs and freight economics.

It also represents something rare: a rapid-transit line that is neither fully “subway” nor merely “commuter rail,” but a third category born from Staten Island’s geography and the B&O’s historic strategy. Today’s Staten Island Railway is the surviving spine of a once-larger network—an everyday commuter utility, a living artifact of railroad-era transit planning, and a reminder that New York’s transit future has always been shaped as much by what didn’t get built as by what did.

Recent Articles

-

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 Returns To Life

Feb 24, 26 11:12 AM

The whistle of Northern Pacific steam returned to the Yakima Valley in a big way this month as Northern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 1364 moved under its own power for the first time in 73 years. -

CSX’s 2025 Santa Train: 83 Years of Holiday Cheer

Feb 24, 26 10:38 AM

On Saturday, November 22, 2025, CSX’s iconic Santa Train completed its 83rd annual run, again turning a working freight railroad into a rolling holiday tradition for communities across central Appalac… -

Alabama Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:25 AM

There is currently one location in the state offering a murder mystery dinner experience, the Wales West Light Railway! -

Rhode Island Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:21 AM

Let's dive into the enigmatic world of murder mystery dinner train rides in Rhode Island, where each journey promises excitement, laughter, and a challenge for your inner detective. -

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:20 AM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Tennessee Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 24, 26 09:17 AM

One of the most unique and enjoyable ways to savor the flavors of Tennessee’s vineyards is by train aboard the Tennessee Central Railway Museum. -

Southeast Wisconsin Eyes New Lakeshore Passenger Rail Link

Feb 23, 26 11:26 PM

Leaders in southeastern Wisconsin took a formal first step in December 2025 toward studying a new passenger-rail service that could connect Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Chicago. -

MBTA Sees Over 29 Million Trips in 2025

Feb 23, 26 11:14 PM

In a milestone year for regional public transit, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) reported that its Commuter Rail network handled more than 29 million individual trips during 2025… -

Historic Blizzard Paralyzes the U.S. Northeast, Halts Rail Traffic

Feb 23, 26 05:10 PM

A powerful winter blizzard sweeping the northeastern United States on Monday, February 23, 2026, has brought transportation networks to a near standstill. -

Mt. Rainier Railroad Moves to Buy Tacoma’s Mountain Division

Feb 23, 26 02:27 PM

A long-idled rail corridor that threads through the foothills of Mount Rainier could soon have a new owner and operator. -

BNSF Activates PTC on Former Montana Rail Link Territory

Feb 23, 26 01:15 PM

BNSF Railway has fully implemented Positive Train Control (PTC) on what it now calls the Montana Rail Link (MRL) Subdivision. -

Cincinnati Scenic Railway To Acquire B&O GP30

Feb 23, 26 12:17 PM

The Cincinnati Scenic Railway, through an agreement with the Raritan Central Railway, to acquire former B&O GP30 #6923, currently lettered as RCRY #5. -

Texas Dinner Train Rides On The TSR

Feb 23, 26 11:54 AM

Today, TSR markets itself as a round-trip, four-hour, 25-mile journey between Palestine and Rusk—an easy day trip (or date-night centerpiece) with just the right amount of history baked in. -

Iowa Dinner Train Rides On The B&SV

Feb 23, 26 11:53 AM

If you’ve ever wished you could pair a leisurely rail journey with a proper sit-down meal—white tablecloths, big windows, and countryside rolling by—the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad & Museum in Boon… -

North Carolina Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:48 AM

A noteworthy way to explore North Carolina's beauty is by hopping aboard the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad and sipping fine wine! -

Nevada Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 23, 26 11:43 AM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

Reading & Northern Surpasses 1M Tons Of Coal For 3rd Year

Feb 22, 26 11:57 PM

Reading & Northern Railroad (R&N), the largest privately owned railroad in Pennsylvania, has shipped more than one million tons of Anthracite coal for the third straight year. This was an impressive f… -

Minnesota's Northstar Commuter Rail Ends Service

Feb 22, 26 11:43 PM

Metro Transit has confirmed that Northstar service between downtown Minneapolis (Target Field Station) and Big Lake has ceased, with expanded bus service along the corridor beginning Jan. 5, 2026. -

Tri-Rail Sets New Ridership Record in 2025

Feb 22, 26 11:24 PM

South Florida’s commuter rail service Tri-Rail has achieved a new annual ridership milestone, carrying more than 4.5 million passengers in calendar year 2025. -

CSX Completes Major Upgrades at Willard Yard

Feb 22, 26 11:14 PM

In a significant boost to freight rail operations in the Midwest, CSX Transportation announced in January that it has finished a comprehensive series of infrastructure improvements at its Willard Yard… -

New Hampshire Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:39 AM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

New Jersey Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:37 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Nevada Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:36 AM

Seamlessly blending the romance of train travel with the allure of a theatrical whodunit, these excursions promise suspense, delight, and an unforgettable journey through Nevada’s heart. -

West Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 22, 26 09:34 AM

For those looking to combine the allure of a train ride with an engaging whodunit, the murder mystery dinner trains offer a uniquely thrilling experience. -

New York Central 4-8-2 #3001 To Be Restored

Feb 22, 26 12:29 AM

New York Central 4-8-2 No. 3001—an L-3a “Mohawk”—is the centerpiece of a major operational restoration effort being led by the Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society (FWRHS) and its American Locomotiv… -

Norfolk Southern To Buy 40 New Wabtec ES44ACs

Feb 21, 26 11:52 PM

Norfolk Southern has announced it will acquire 40 brand-new Wabtec ES44AC locomotives, marking the Class I railroad’s first purchase of new locomotives since 2022. -

CPKC To Buy 65 New Progress Rail SD70ACe-T4s

Feb 21, 26 11:28 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) is moving to refresh and expand its road fleet with a new-build order from Progress Rail, announcing an agreement for 65 EMD SD70ACe-T4 Tier 4 diesel-electric freig… -

Ohio Rail Commission Approves Two Projects

Feb 21, 26 11:09 PM

At its January 22 bi-monthly meeting, the Ohio Rail Development Commission approved grant funding for two rail infrastructure projects that together will yield nearly $400,000 in investment to improve… -

CSX Completes Avon Yard Hump Lead Extension

Feb 21, 26 03:38 PM

CSX says it has finished a key infrastructure upgrade at its Avon Yard in Indianapolis, completing the “cutover” of a newly extended hump lead that the railroad expects will improve yard fluidity. -

Pinsly Restores Freight Service On Alabama Short Line

Feb 21, 26 12:55 PM

After more than a year without trains, freight rail service has returned to a key industrial corridor in southern Alabama. -

Phoenix City Council Pulls the Plug on Capitol Light Rail Extension

Feb 21, 26 12:19 PM

In a pivotal decision that marks a dramatic shift in local transportation planning, the Phoenix City Council voted to end the long-planned Capitol light rail extension project. -

Norfolk Southern Unveils Advanced Wheel Integrity System

Feb 21, 26 11:06 AM

In a bid to further strengthen rail safety and defect detection, Norfolk Southern Railway has introduced a cutting-edge Wheel Integrity System, marking what the Class I carrier calls a significant bre… -

CPKC Sets New January Grain-Haul Record

Feb 21, 26 10:31 AM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) says it has opened 2026 with a new benchmark in Canadian grain transportation, announcing that the railway moved a record volume of grain and grain products in Janu… -

New Documentary Charts Iowa Interstate's History

Feb 21, 26 12:40 AM

A newly released documentary is shining a spotlight on one of the Midwest’s most distinctive regional railroads: the Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS). -

LA Metro’s A Line Extension Study Forecasts $1.1B in Economic Output

Feb 21, 26 12:38 AM

The next eastern push of LA Metro’s A Line—extending light-rail service beyond Pomona to Claremont—has gained fresh momentum amid new economic analysis projecting more than $1.1 billion in economic ou… -

Age of Steam Acquires B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 (2025)

Feb 21, 26 12:33 AM

When the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum rolled out B&LE 2-10-4 No. 643 for public viewing in 2025, it wasn’t simply a new exhibit debuting under roof—it was the culmination of one of preservation’s lo… -

NCDOT Study: Restoring Asheville Passenger Rail Offers Economic Lift

Feb 21, 26 12:26 AM

A revived passenger rail connection between Salisbury and Asheville could do far more than bring trains back to the mountains for the first time in decades could offer considerable economic benefits. -

Brightline Unveils ‘Freedom Express’ To Commemorate America’s 250th

Feb 20, 26 11:36 AM

Brightline, the privately operated passenger railroad based in Florida, this week unveiled its new Freedom Express train to honor the nation's 250th anniversary. -

Age of Steam Roundhouse Adds C&O No. 1308

Feb 20, 26 10:53 AM

In late September 2025, the Age of Steam Roundhouse Museum in Sugarcreek, Ohio, announced it had acquired Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 No. 1308. -

Reading & Northern Announces 2026 Excursions

Feb 20, 26 10:08 AM

Immediately upon the conclusion of another record-breaking year of ridership in 2025, the Reading & Northern Passenger Department has already begun its 2026 schedule of all-day rail excursion. -

Siemens Mobility Tapped To Modernize Tri-Rail Fleet

Feb 20, 26 09:47 AM

South Florida’s Tri-Rail commuter service is preparing for a significant motive-power upgrade after the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) announced it has selected Siemens Mobili… -

Reading T-1 No. 2100 Restoration Progress

Feb 20, 26 09:36 AM

One of the most famous survivors of Reading Company’s big, fast freight-era steam—4-8-4 T-1 No. 2100—is inching closer to an operating debut after a restoration that has stretched across a decade and… -

C&O Kanawha No. 2716: A Third Chance at Steam

Feb 20, 26 09:32 AM

In the world of large, mainline-capable steam locomotives, it’s rare for any one engine to earn a third operational career. Yet that is exactly the goal for Chesapeake & Ohio 2-8-4 No. 2716. -

Missouri Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:29 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:26 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure. -

Kansas Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:23 AM

Kansas, known for its sprawling wheat fields and rich history, hides a unique gem that promises both intrigue and culinary delight—murder mystery dinner trains. -

Florida Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 20, 26 09:20 AM

Florida, known for its vibrant culture, dazzling beaches, and thrilling theme parks, also offers a unique blend of mystery and fine dining aboard its murder mystery dinner trains. -

NC&StL “Dixie” No. 576 Nears Steam Again

Feb 20, 26 09:15 AM

One of the South’s most famous surviving mainline steam locomotives is edging closer to doing what it hasn’t done since the early 1950s, operate under its own power. -

Frisco 2-10-0 No. 1630 Continues Overhaul

Feb 19, 26 03:58 PM

In late April 2025, the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) made a difficult but safety-minded call: sideline its famed St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) 2-10-0 No. 1630. -

PennDOT Pushes Forward Scranton–New York Passenger Rail Plan

Feb 19, 26 12:14 PM

Pennsylvania’s long-discussed idea of restoring passenger trains between Scranton and New York City is moving into a more formal planning phase.