Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O): Map, History, Logo

Last revised: December 7, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Baltimore and Ohio, “Linking 13 Great States With The Nation.” This was the railroad's slogan to which it remained devoted for many years.

The B&O holds the distinction as being this country’s very first common-carrier railroad (chartered specifically for public use), officially created in 1827.

Its early years were plagued with frustrations as it was blocked by the state of Pennsylvania on numerous occasions in the western route of its choosing, forced instead to rely upon a much more rugged line through Maryland and western Virginia (later West Virginia).

Despite these setbacks, the upheaval of the Civil War, and other issues the B&O grew into a powerful railroad stretching more than 10,000 total miles of track.

It has long been regarded as the third major trunk line to Chicago behind rivals Pennsylvania and New York Central.

The B&O is also fondly remembered for providing friendly and high quality service until the end despite a declining financial condition during the post-World War II years.

Its takeover by the Chesapeake & Ohio in the early 1960s helped ensure its survival and it eventually joined the Chessie System family before disappearing into CSX Transportation during the 1980s.

It's a busy scene in this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo taken at Sir Johns Run, West Virginia during the early 1950s; a nice A-B-B-A lash-up of FT's are ahead of a westbound manifest to left while 2-6-6-4 #7705 (KB-1a), a former Seaboard Air Line engine, leads another to the right. An eastbound coal drag can be seen in the background. American-Rails.com collection.

It's a busy scene in this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo taken at Sir Johns Run, West Virginia during the early 1950s; a nice A-B-B-A lash-up of FT's are ahead of a westbound manifest to left while 2-6-6-4 #7705 (KB-1a), a former Seaboard Air Line engine, leads another to the right. An eastbound coal drag can be seen in the background. American-Rails.com collection.History

As this country’s first common carrier railroad the B&O was instrumental in growing and stimulate our nation's economy during a time when “West” meant the Ohio River.

While never a wealthy company its legacy will forever be remembered as a survivor and putting customer service above all else.

This dedication earned the B&O a loyal following to the extent that some folks steadfastly rode its trains even if they were somewhat slower than that of its rivals.

In addition, as Brian Solomon notes in his book, "Amtrak," his grandfather, a regular rail traveler during the early 20th century, noted the B&O offered the best dining services.

When the company’s existence finally came to an end on April 30, 1987 it had just celebrated its 160th birthday and witnessed the industry grow from nothing more than few scattered lines to a rail network consisting of tens of thousands of miles linking the country from coast to coast (it also outlived its wealthier northern competitors by more than a decade).

At A Glance

The B&O was largely created out of a great need by the city of Baltimore to compete with the creation of the Erie Canal, which connected New York City with the Port of Albany at Buffalo. In addition, Philadelphia was organizing a plan to build a similar transportation system across the state linking Pittsburgh.

Fearing its city would be left at an economic disadvantage Baltimore leaders formed the B&O, originally chartered on February 28, 1827 and officially incorporated and organized on April 24, 1827. By that Fourth of July construction began with laying of a cornerstone in the city.

According to the book, "Baltimore & Ohio Railroad," by Kirk Reynolds and David Oroszi it was tradition to launch new canal construction on July 4th and since the B&O was a similar transportation artery Independence Day was chosen.

There were celebrations and ceremonies to mark the occasion and Charles Carroll himself, the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence, was on-hand to take part in the festivities. He was given the task of turning the first shovel of dirt, signaling the B&O's construction was underway.

The goal was having the railroad reach the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia and connect Cumberland, Maryland along the way. However, the task would be very difficult as the rugged Allegheny Mountains lay in its path.

The company would also face stiff political barriers from Pennsylvania, restricting an easier route through that state and forcing it to build across western Virginia.

The B&O's immediate concern was simply building a rail line; as a true pioneer, nearly everything decision it made was an educated guess based on what little was known about trains at the time.

Perhaps most challenging was constructing a proper right-of-way and figuring out the curvature limits and grade severity a typical train could handle. To aid in this endeavor engineers sailed to England, the birthplace of railroads, for ideas concerning construction and best practices.

Among their most notable takeaways was track gauge. In his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," author and historian Dr. George W. Hilton notes the B&O was initially built to a gauge of 4 feet, 6 inches.

However, after its engineers studied English railways and witnessed how their gauge of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches provided for more room of moving parts on inside-connected locomotives, it was adopted and in use by the early 1830's. The B&O's next task was in designing a track guideway for the trains' wheels to follow.

The transition from steam to diesel was a fascinating era in American railroading. Here, Baltimore & Ohio E7A #66 (about a year old) and 4-6-2 #5086 (Class P-1a) await their next assignments in Cumberland, Maryland during October, 1946.

The transition from steam to diesel was a fascinating era in American railroading. Here, Baltimore & Ohio E7A #66 (about a year old) and 4-6-2 #5086 (Class P-1a) await their next assignments in Cumberland, Maryland during October, 1946.Once again, engineers found themselves in unknown territory as they experimented with various techniques from stone guideways with wooden beams to iron straps using the same principle.

They eventually learned the best, most economical design was a wooden beam reinforced with a iron strap supported by wooden crossties.

Iron strap rails did work although proved incredibly dangerous as worn straps could let go causing the deadly phenomenon of "snake heads," which easily ripped through the floors of early wooden cars and maimed or killed passengers.

By the 1840s solid iron "T"-rail was introduced, developed by Robert Stevens president of the Camden & Amboy Railroad. In January of 1830 the B&O launched service over its first 1.5 miles from a small station in Baltimore at Pratt Street.

Within just a few months, 13 miles was opened to Ellicotts Mills (today Ellicott City) in May where the railroad constructed a sturdy, two-story stone depot along with a small turntable.

The location did not offer significant passenger traffic but did serve a local granite quarry, known as Ellicott's Quarries, along with nearby agriculture and less-than-carload freight.

These early trains all operated with horses as power, trotting along with what was little more than retrofitted carriages.

In this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo, handsome FA-2's have westbound coal drags at Orleans, West Virginia during the early 1950's.

In this Baltimore & Ohio publicity photo, handsome FA-2's have westbound coal drags at Orleans, West Virginia during the early 1950's.That same summer on August 28th the B&O successfully tested Peter Cooper's 2-2-0 "Tom Thumb," a Planet Type steam locomotive. It lost its famous race with a horse that day but successfully proved the viability of steam-powered locomotives.

In early 1831 the B&O placed an order from Phineas Davis of York, Pennsylvania for an 0-4-0 steamer called the York and in time the railroad retired its stable of horses for the iron horse.

As the 1830s progressed the B&O continued expansion towards the west reaching Frederick in 1831 (via a branch) and Harpers Ferry, Virginia in January, 1837 following a completion of a bridge spanning the Potomac River.

System Map

As construction quickened Cumberland was finally reached on November 5, 1842, a location that throughout the railroad’s existence would be a major division point.

A further push to the west bogged down as the B&O focused on upgrading its existing property. Unfortunately, by the 1840s the railroad was no longer alone as many other new charters and companies were being formed, notably the Pennsylvania Railroad (1846).

Baltimore & Ohio F7's lead their freight train eastbound through the once-important division point of Martinsburg, West Virginia on October 11, 1969. Roger Puta photo.

Baltimore & Ohio F7's lead their freight train eastbound through the once-important division point of Martinsburg, West Virginia on October 11, 1969. Roger Puta photo.Under the new direction of Thomas Swann, who achieved the presidency on October 11, 1848, the railroad was soon under construction again in an effort to complete its charter; heading roughly southwest it reached the small community of Bridge Valley (later Grafton) and Fairmont, Virginia before turning northwesterly towards the Ohio River.

Finally, in 1852 it had reached the City of Wheeling, Virginia (West Virginia after June 20, 1863) along the river. It was not long before the B&O was again pushing west from Grafton (founded on March 15, 1856 and named after John Grafton), this time heading due west to the Ohio River at Parkersburg where it connected with the Marietta & Cincinnati.

Downtown Baltimore Map (1848)

Through a series of mergers and acquisitions the railroad had reached St. Louis by 1857 via Cincinnati, Ohio thus linking eastern markets with the Mississippi River.

After recovering from the Civil War's destruction the company reached Chicago by 1875 (albeit indirectly, its through route to the Windy City, via Pittsburgh, was not established until 1891).

Baltimore & Ohio FPA-2 #810 and FB-2's receive a bath at the wash rack in Willard, Ohio on August 14, 1956. J.W. Swanberg photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore & Ohio FPA-2 #810 and FB-2's receive a bath at the wash rack in Willard, Ohio on August 14, 1956. J.W. Swanberg photo. American-Rails.com collection.Following its Chicago link the B&O eyed better easterly connections at Philadelphia and New York to better compete against a Pennsylvania Railroad that, by then, had already established itself as the dominate road to those cities.

It opened between Philadelphia and Baltimore (111 miles) in September of 1886 by way of subsidiary Delaware Western.

The only way for the B&O to reach New York City was thanks to friendly connections over the Philadelphia & Reading (Philadelphia - Bound Brook) and Central Railroad of New Jersey (Bound Brook - Jersey City).

What became known as its "Royal Blue Line" was actually a patch work of through connections and passengers had to disembark from the CNJ's Jersey City Terminal where they rode ferries across the Hudson River into Manhattan.

This setup obviously put the B&O at a disadvantage in the market but it faithfully fought hard with an elegant train known as the Royal Blue before giving up in 1958.

Predecessors

Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal

Arguably the most important B&O Railroad subsidiary was the B&OCT, which provided crucial switching and terminal operations within the Windy City not only for its parent but also numerous surrounding railroads.

It was formed in 1910 when the B&O acquired the bankrupt Chicago Terminal Transfer Railroad.

The CTTR itself had a long history of predecessors dating back to the La Salle & Chicago Railroad of 1867. At its peak the B&OCT operated from Chicago Heights to Franklin Park via Blue Island and La Grange.

It also connected Bellwood, Forest Hill, South Chicago, East Chicago, Calumet Park, Whiting, and Pine Junction. The B&OCT offered its parent direct access to its Grand Central Station along Chicago's North Side. Today, the company is still a subsidiary of CSX Transportation.

Baltimore, Pittsburgh & Chicago

A wholly-owned subsidiary of the B&O, the BP&C was incorporated in March of 1872 to build a 260-mile extension from a point known as Chicago Junction, Ohio (later renamed Willard after noted B&O president Daniel Willard).

In 1873 the line reached Newark, Ohio and was completed to Chicago by 1875. At first the B&O used the Illinois Central to reach the Windy City's downtown area but later established a successful terminal road, the Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal, to handle the daily tasks of operations throughout the city.

The railroad's initial passenger terminal here was located along Adams Street although by 1883 it had an improved facility near Monroe Street. Finally, the B&O moved into the handsome Grand Central Station in 1891, which became its primary terminal until passenger services ended three-quarters of a century later.

Baltimore & Ohio GP38 #4804 and F7A #4566 layover in Grafton, West Virginia in November, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore & Ohio GP38 #4804 and F7A #4566 layover in Grafton, West Virginia in November, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh

The BR&P was a regional line linking central Pennsylvania with Buffalo and Rochester, New York. It was pieced together primarily to handle coal traffic and was acquired by the B&O in 1929 which formally took over the property on January 1, 1932.

The BR&P's corporate history began on March 10, 1887 when the Pittsburgh & State Line Railroad and the first Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh merged following the bankruptcy of the Rochester & Pittsburgh.

Then-president Daniel Willard was attempting to push the B&O into key western New York markets although the BR&P never offered the greatest connection to Buffalo.

He also purchased a nearby road known as the Buffalo & Susquehanna in 1932, created in 1893 through the merger of several small logging lines including the Sinnemahoning Valley Railroad, Susquehanna Railroad, Cherry Springs Railroad, Cross Fork Railroad, and an earlier Buffalo & Susquehanna.

It ran diagonally across Pennsylvania from Sagamore to Addison and Wellsville, New York via Galeton. There were also branches to Ansonia and Keating Summit, Pennsylvania.

The road struggled financially and never earned much revenue, even during B&O control, relying largely on sparse local industry and agriculture.

Heavy flooding in November of 1942 forced the abandonment of the B&S south of Galeton, isolating it from the B&O network. The northern segment was later sold to form the Wellsville, Addison & Galeton in 1956. It operated freight service until 1979.

Marietta & Cincinnati Railroad

The M&C initially carried no ties to the B&O although the Baltimore road saw it as an important link to the Midwest. The M&C was formed in 1851 by the consolidation of the Belpre & Cincinnati and Franklin & Ohio railroads.

Its funding came primarily from the towns it would connect such as Athens, Cincinnati, Marietta, and Chillicothe.

The road opened in early 1857 between Marietta and Cincinnati, establishing a link to the B&O/NV via carferry service from Parkersburg to Marietta.

After many years the B&O was finally able to construct a large, 7,100-foot bridge across the Ohio River from Parkersburg to Belpre, Ohio opening for service on January 7, 1871 and eliminating the car-ferry operation. The B&O gained control of the M&C in 1882 and renamed it has the Baltimore & Ohio Southwestern in 1889.

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4499 and GP9 #6496 swing off the Chicago main line and onto the Somerset & Cambria Branch at Rockwood, Pennsylvania in June, 1967. The Western Maryland connection can be seen overhead. E. Roy Ward photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4499 and GP9 #6496 swing off the Chicago main line and onto the Somerset & Cambria Branch at Rockwood, Pennsylvania in June, 1967. The Western Maryland connection can be seen overhead. E. Roy Ward photo. American-Rails.com collection.Northwestern Virginia Railroad

The NV provided the B&O with a more direct western routing from Cumberland. While its original main line to Wheeling offered access to the Ohio River and a connection with the National Road the company began searching for a better river port centered more geographically towards the Midwest.

On February 14, 1851 the Northwestern Virginia Railroad was chartered to connect with the B&O at what later became Grafton, winding its way along the Appalachian foothills to Parkersburg, Virginia.

Although the NV was a private corporation it was largely backed by the B&O and formally leased during December of 1856.

The railroad opened for service on May 1, 1857 and became known as the "Parkersburg Branch." The corridor, despite being riddled with sharp curves, tunnels, and stiff grades became an integral link of the B&O's St. Louis main line/Monongah Division.

It always carried the moniker, "Parkersburg Branch," until its abandonment in the 1980s. For a complete history of the Parkersburg Branch please click here.

Pittsburgh & Connellsville Railroad

The P&C was first organized in 1837 and eventually began construction in 1847 as the B&O helped fund the project to reach the Steel City.

The railroad battled with the state and rival Pennsylvania Railroad for control of the P&C, eventually winning in court in 1868. The road, including its famous Sand Patch Grade, was completed from Pittsburgh to Cumberland in May of 1871.

It became a vital component in the B&O's Chicago main line. Soon after the line opened the B&O gained additional access to Pittsburgh from the west via Wheeling (the Wheeling, Pittsburgh & Baltimore) and the south via Fairmont/Morgantown (the Fairmont, Morgantown & Pittsburgh, also remembered as the "Sheepskin Line").

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4563 sits at the west end of the High Yard in Parkersburg, West Virginia near OB Tower as the locomotive awaits departure to the west; February, 1974. Parkersburg was once a major division point along the St. Louis main line. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4563 sits at the west end of the High Yard in Parkersburg, West Virginia near OB Tower as the locomotive awaits departure to the west; February, 1974. Parkersburg was once a major division point along the St. Louis main line. American-Rails.com collection.Ohio & Mississippi Railway

The O&M was the B&O's link beyond Cincinnati to St. Louis. It began construction in 1854 and was completed in 1857 at around the same time as the M&C and NV.

It also constructed two branches, one linking Jeffersonville, Indiana near Louisville, Kentucky and the other connecting Shawneetown with Beardstown, Illinois via Flora.

The route was originally built to 6-foot gauge and later converted to standard gauge in July of 1871. In 1893 the B&O formally acquired the O&M and integrated it into the B&O Southwestern in 1900.

Ohio River Rail Road

The ORRR began construction south of Wheeling, West Virginia in 1882, backed with funding from the Rockefeller/Standard Oil interests. It was completed to Huntington, West Virginia in 1888 as it closely paralleled its namesake river.

In time oil and petrochemical industries sprang up along the route as the B&O took an interest in the property. It leased the ORRR during September of 1901 and purchased it in 1912.

The line not only offered growing freight traffic but also linked the B&O's main lines at Wheeling and Parkersburg while a southerly connection was established with the Chesapeake & Ohio at Huntington/Kenova.

A Baltimore & Ohio FA-2/FB-2 set has train #34 heading eastbound through historic Harpers Ferry, West Virginia as it crosses the Potomac River in the spring of 1956. Clarence Cade photo.

A Baltimore & Ohio FA-2/FB-2 set has train #34 heading eastbound through historic Harpers Ferry, West Virginia as it crosses the Potomac River in the spring of 1956. Clarence Cade photo.Virginia Extension

As the B&O carried out its rapid expansion after the Civil War it fanned out in all directions, including the Deep South.

This idea was quite unique for an eastern road and had it been successful would likely have provided the B&O an important connection with systems like the Southern and Norfolk & Western.

Its first acquisition occurred on July 1, 1867 when it leased the Winchester & Potomac running 22 miles from its main line at Harpers Ferry to Winchester, Virginia.

It then acquired the 19-mile Winchester & Strasburg while in 1873 the Virginia Midland offered access as far south as Harrisonburg via Strasburg (50 miles) once completed the following year.

As it continued its push down the Shenandoah Valley the B&O-backed Valley Railroad, aiming for Salem (near Roanoke), made it only as far as Lexington in 1883 before further construction ceased.

The Baltimore road was busy with other ventures and with little local public support to complete the extension the VRR withered.

In 1896 the B&O, attempting to restructure its finances following bankruptcy sold its northern interests and the great project's fate was sealed. The VRR operated until the early 1940s when operations were suspended.

At the B&O’s peak the railroad served the markets of New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, and St. Louis via more than 6,000 route miles (over 10,000 miles in total). The B&O was always the underdog in an eastern market dominated by the PRR and NYC.

The company also had an on-and-off again struggle to remain independent as it once went into receivership in early 1896 and later ownership by the PRR. However, throughout it all the road steadfastly carried a pride that held true until its final days under CSX.

A Baltimore & Ohio F7A rolls southbound along 2nd Street in St. Marys, West Virginia during a summer's day in the 1960s (the tankers in the consist are likely loaded with product from the Quaker State Refinery just behind the photographer to the right about a 1/4-mile away). Pay no mind to the City Tire Shop pickup, trains have been rolling along this street trackage since the 1880s, at about 10 mph, with only two known minor fender benders during that time. John King photo.

A Baltimore & Ohio F7A rolls southbound along 2nd Street in St. Marys, West Virginia during a summer's day in the 1960s (the tankers in the consist are likely loaded with product from the Quaker State Refinery just behind the photographer to the right about a 1/4-mile away). Pay no mind to the City Tire Shop pickup, trains have been rolling along this street trackage since the 1880s, at about 10 mph, with only two known minor fender benders during that time. John King photo.Despite its marginal financial situation the B&O holds many “firsts.” It was quick to adopt the more efficient mode of diesel power in 1930s and the first to include air-conditioning on its passenger trains.

Other accomplishments included the first to place electric locomotives in service (through its Howard Street tunnel in Baltimore, a project developed in conjunction with General Electric), championed the use of streamlined passenger trains early on, and pioneered dome cars in the eastern United States (tight clearances had largely restricted these east of the Mississippi River).

The B&O’s financial situation would, however, eventually catch up with it as a severe national recession in the 1950s saw the company in a serious situation and facing bankruptcy by the early 1960s.

It had been skillfully headed by Daniel Willard from 1910 until June of 1941, guiding the company through the struggles of World War I and the Great Depression era.

In his place stepped Roy White who also did a superb job through the World War II era. The 1950s, however, proved more problematic and new president Howard Simpson had to deal with these issues.

As traffic slipped, eroded by other modes of transportation, the road struggled after 1956 to sustain profitability.

It tried many tactics to curb losses, from slicing down its payroll to implementing new types of freight service such as intermodal/trailer-on-flat-car (TOFC). These efforts helped but by 1960 the B&O was showing significant losses.

Perhaps as a blessing the modern merger movement began at that time, kicked off by the Norfolk & Western's purchase of the Virginian Railway in 1959.

Baltimore & Ohio F7's are just east of Cumberland, Maryland with a general manifest during a spring day in the 1950s. Author's collection.

Baltimore & Ohio F7's are just east of Cumberland, Maryland with a general manifest during a spring day in the 1950s. Author's collection.C&O Acquisition

During this time the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway (C&O) took an interest in the company and would later win a battle with the NYC for control of the B&O.

After a drawn out process, Chessie was declared the victor. The Interstate Commerce Commission formally approved the merger on December 31, 1962.

A few months later, on February 4, 1963 the C&O took direct control. The B&O was to suffer a better fate than either the NYC or PRR, which would merge in 1968 to form the ill-fated Penn Central Corporation.

Chessie System

The C&O, for several reasons, chose to leave the B&O almost entirely independent, only gradually merging the operational aspects of both companies.

This finally changed in 1972 when both, including B&O-subsidiary Western Maryland, formed a holding company called the Chessie System in which all three were included.

An entire new livery was drawn up featuring a brilliant yellow, blue, and vermilion paint scheme adorned with a Chess-"C" silhouette of the C&O's famous Chessie the kitten napping on her pillow.

Baltimore Belt Railroad

The Baltimore Belt Railroad and Howard Street Tunnel project undertaken by the Baltimore & Ohio essentially kicked off electrified rail operations in the United States when it began service in 1895 (in 1888 when General Electric successfully demonstrated the motive power on the Richmond Union Passenger Railway).

The B&O’s project was constructed to fill a gap by connecting the railroad’s New York-Washington (north-south) and Washington – Cumberland (east-west) main lines.

According to the railroad's "Official List No. 29" issued January 1, 1948 notes the territory covered 7.2 miles from Milepost 90.7 at Bay View, Maryland to Milepost 97.9 at Hamburg Street, Baltimore.

Of this, 4 miles was electrified. Prior to this project it had used a circuitous car ferry operation across Baltimore Harbor, which made competing effectively with rival Pennsylvania Railroad nearly impossible.

After the first successful demonstration in Richmond, which involved a lightly powered locomotive, the motive power sprang up on light rail, interurban, and trolley systems all across the country.

The B&O's system used a 600 volt direct current system with four gearless, 360 horsepower, locomotives (or “motors” as electrics are often called).

The primary reason for the B&O’s Baltimore Belt Railroad was to solve a safety issue with its 1.4-mile long tunnel situated under residential neighborhoods where smoke would become a health issue.

Even by the late 19th century steam locomotives in large urban areas were becoming a serious health and safety issue due to their suffocating smoke and impairing vision.

The issue became all too real when a New York Central train collided with a New Haven suburban run in January of 1902 within New York City due to a smoke-obscured signal.

The result of this incident banned steam within downtown Manhattan and other cities began passing similar ordinances.

In all the B&O’s electrified system stretched three miles with initial power provided by General Electric that employed “steeple cab” electrics. First operated on May 1, 1895 the new line used steam locomotives fired by coke, which burned much cleaner than coal.

Electric Locomotive Classes

In all, the B&O employed six different classes of electric locomotives, which are listed below:

· Class LE-1: B&O’s first class of motors were delivered in 1895 and 1896 and were of a steeple-cab design totaling three units.

· Class LE-2: B&O’s second-class of motors were delivered between 1903 and 1906 by GE and were a boxcab design totaling four units.

· Class OE-1: B&O’s third-class of motors were delivered in 1910 by GE and were a steeple-cab design totaling two units.

· Class OE-2: B&O’s fourth-class of motors were delivered in 1912 by GE and were a steeple-cab design totaling two units.

· Class OE-3: B&O’s fifth-class of motors were delivered in 1923 by GE and were a steeple-cab design totaling two units.

· Class OE-4: B&O’s sixth, and final class of motors were delivered in 1923 by GE and were a steeple-cab design totaling two units.

Finally, the electrified system was completed about a month later and the first electrically powered train completed a test run on June 27th.

A few days later, on July 1st, the B&O introduced the revolutionary new mode of transportation to the public.

Initially, the company employed an overhead third-rail system, whereby “shoes” picked up power, similar to later overhead systems that used strung wires (catenary).

However, this system proved vulnerable to coal smoke and by 1900 a conventional third-rail system running near the ground was used.

One other addition was the railroad’s beautiful Mount Royal Station, constructed at the north end of Howard Street Tunnel. Today, the station remains in place and has been beautifully restored.

Final Years

The Chessie System, by far one of the best-loved railroad liveries ever created lasted only a short eight years; in 1980 the Chessie roads and those of the Family Lines/Seaboard Coast Line Industries (which was a holding company for a number of southeastern railroads including the Seaboard Coast Line and Louisville & Nashville) to form CSX Corporation on November 1st.

The creation of CSX entered the B&O into its last of many long and storied chapters. By now the company was merely a "paper" railroad (remaining in existence partly because of a tax exemption it retained in its home state of Maryland) and would be gone in only seven more years.

Passenger Trains

According to Trains Magazine, the Western Maryland was the first to disappear, merged into the B&O on May 1, 1983. The B&O survived until April 30, 1987 when it disappeared into the C&O (ironically it had just celebrated its 160th birthday on April 24th). Finally, the C&O was formally dissolved as a corporate entity on August 31, 1987.

Baltimore & Ohio Geeps, led by GP35 #3542, are southbound near Chippewa Lake, Ohio on the CL&W Subdivision (Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling); August 20, 1978. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore & Ohio Geeps, led by GP35 #3542, are southbound near Chippewa Lake, Ohio on the CL&W Subdivision (Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling); August 20, 1978. American-Rails.com collection.Alas, the 1980s and the years to follow were not good for the former B&O lines as CSX began a long and continued campaign of abandoning or selling lines it deemed redundant/unprofitable. Unfortunately, large sections of its network were deemed as such.

In 1985, just as the intermodal container revolution was gaining steam, CSX announced intentions to sever its St. Louis main line between Clarksburg and Parkersburg, West Virginia (the "Parkersburg Branch") as well as much of the Ohio Division.

When the intermodal business truly took off soon afterwards CSX was left without a market to move containers competitively until its acquisition of Conrail in 1999.

This event has long since been questioned and had the line been left in place, upgraded to carry double-stack containers it would likely be profitable today, offering the shortest distance between the St. Louis gateway and east coast.

Diesel Roster

Steam Roster (Post 1900)

Notable Steam Classes

Class E (2-8-0)

Class EL (2-8-8-0)

Class EM-1 (2-8-8-4)

Class KB-1 (2-6-6-4)

Class KK (2-6-6-2)

Class KL-1 (2-6-8-0)

Class LL-1 (0-8-8-0)

Class N-1 (4-4-4-4)

Class P (4-6-2)

Class Q (2-8-2)

Class T (4-8-2)

Class V (4-6-4)

A pair of Chessie System/B&O GP40-2's lead an eastbound hotshot "Philadelphia Trailerjet" along the St. Louis main line near Porterfield, Ohio in June of 1981. Today, this right-of-way lies empty. Author's collection.

A pair of Chessie System/B&O GP40-2's lead an eastbound hotshot "Philadelphia Trailerjet" along the St. Louis main line near Porterfield, Ohio in June of 1981. Today, this right-of-way lies empty. Author's collection.While the building of the Baltimore Belt Railroad and its electrified lines helped significantly improve operations in and around Baltimore the project was extremely expensive and forced costly debt on the railroad that helped drive it into bankruptcy in 1896.

Even though the B&O updated its electric fleet from 1909 through 1912, and again between 1923-1927, with diesel-electric locomotives efficient and affordable by the mid-20th century the railroad shut down its electrification in the early 1950's.

Interestingly, today the original Baltimore Belt Railroad remains an important artery under the CSX Transportation banner.

Perhaps Mike Schafer said it best in his book, "Classic American Railroads": although the B&O was never a healthy and extremely profitable railroad it will forever be remembered for:

"...its pioneer spirit, determination in the face of adversity, innovative technology, superior service, courteous employees, and aesthetic equipment," which made it beloved by so many throughout the years.

Heritage Unit, CSX #1827

In May, 2023, CSX Transportation release a heritage locomotive in a Baltimore & Ohio-inspired blue and grey livery, ES44AH #1827.

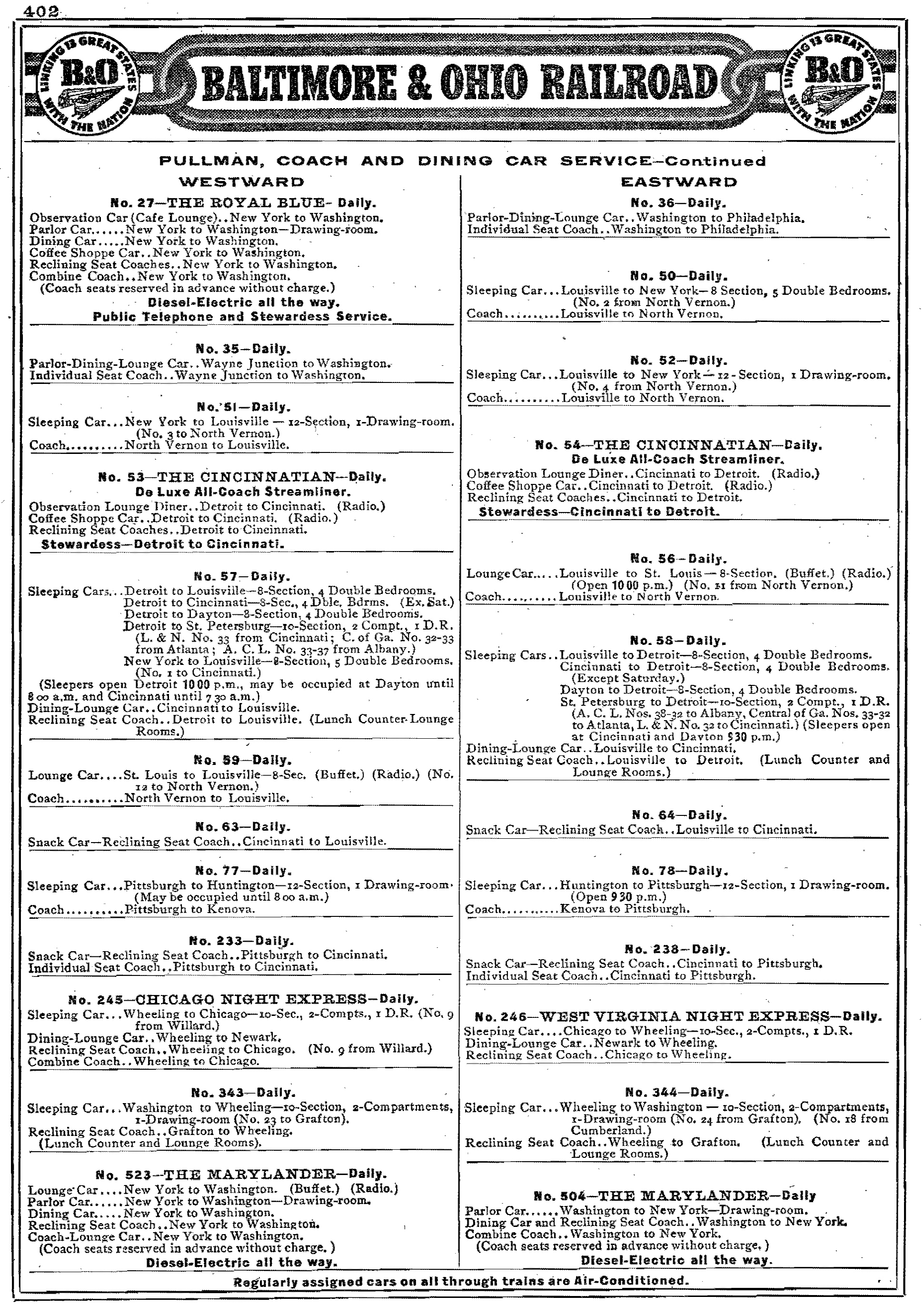

Timetables (1952)

Sources

- Kirkland, John F. Diesel Builders, The: Volume One, Fairbanks-Morse And Lima-Hamilton. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1985.

- Kirkland, John F. Diesel Builders, The: Volume Two, American Locomotive Company And Montreal Locomotive Works. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1989.

- Kirkland, John F. Diesel Builders, The: Volume Three, Baldwin Locomotive Works. Pasadena: Interurban Press, 1994.

- Liljestrand, Robert A. and Sweetland, David R. Baltimore & Ohio Diesel Locomotives: Volume 1, Switchers & Road Switchers.

- Mainey, David. Baltimore & Ohio Steam In Color. Scotch Plains: Morning Sun Books, 2001.

- Reynolds, Kirk and Oroszi, David. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2000.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Solomon, Brian. Electro-Motive E-Units and F-Units: The Illustrated History of North America's Favorite Locomotives. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2011.

Recent Articles

-

Charlotte Approves $37.9M For "Red Line" To Lake Norman

Mar 11, 26 02:18 PM

The Charlotte City Council has approved $37.9 million in funding for the next phase of design work on the long-planned Red Line commuter rail project. -

NS, Progress Rail Announce SD70ICC Modernization

Mar 11, 26 12:15 PM

Norfolk Southern Railway has announced a significant locomotive modernization initiative in partnership with Progress Rail Services Corporation that will rebuild 96 existing road locomotives into a ne… -

Colorado Seeks Input On Proposed Front Range Passenger Train Name

Mar 11, 26 11:55 AM

Colorado officials are inviting the public to help name a proposed passenger train that could one day connect major cities along the state’s heavily traveled Interstate 25 corridor. -

Virginia Whiskey Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 11:22 AM

Among the Virginia Scenic Railway's most popular specialty excursions is the “Bourbon & BBQ” tasting train, an adults-oriented rail journey that pairs scenic views of the Shenandoah Valley with guided… -

Minnesota's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:32 AM

Among the North Shore Scenic Railroad's special events, one consistently rises to the top for adults looking for a lively night out: the Beer Tasting Train. -

New Mexico's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:23 AM

Sky Railway's New Mexico Ale Trail Train is the headliner: a 21+ excursion that pairs local brewery pours with a relaxed ride on the historic Santa Fe–Lamy line. -

Indiana's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:19 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Ohio's Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 11, 26 10:02 AM

The murder mystery dinner train rides in Ohio provide an immersive experience that combines fine dining, an engaging narrative, and the beauty of Ohio's landscapes. -

Kentucky Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 11:39 AM

The Bluegrass State is home to beautiful rolling farms and the western Appalachian Mountain chain, which comes alive each spring. A few railroad museums host Easter-themed events during this time. -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:26 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

NS Faces Multiple Derailments Near Historic Horseshoe Curve

Mar 10, 26 10:15 AM

One of America’s most famous railroad landmarks, the legendary Horseshoe Curve west of Altoona, Pennsylvania, has recently been the site of multiple freight-train derailments involving Norfolk Souther… -

Oregon's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 10:11 AM

If your idea of a perfect night out involves craft beer, scenery, and the gentle rhythm of jointed rail, Santiam Excursion Trains delivers a refreshingly different kind of “brew tour.” -

Arizona's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:57 AM

Verde Canyon Railroad’s signature fall celebration—Ales On Rails—adds an Oktoberfest-style craft beer festival at the depot before you ever step aboard. -

Connecticut's Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:54 AM

If you’re looking for a signature “special occasion” experience, the Essex Steam Train's Wine & Chocolate Dinner Train stands out as a decadent, social, and distinctly memorable take on dinner on… -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 10, 26 09:37 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Union Pacific Restores Rail Bridge Service in Lincoln

Mar 09, 26 11:34 PM

Union Pacific crews have successfully restored freight rail service across a key bridge in Lincoln, Nebraska, completing a rapid reconstruction effort in just a few weeks. -

TVRM To Assist In Gas-Powered Locomotive's Restoration

Mar 09, 26 11:15 PM

The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum has announced it is assisting in the eventual cosmetic restoration of a former gas powered locomotive used in the logging industry. -

Michigan's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:37 AM

Spring sometimes comes late to Michigan but this doesn't stop a handful of the state's heritage railroads from hosting Easter-themed rides. -

Pennsylvania's Easter Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 10:05 AM

Pennsylvania is home to many tourist trains and several host Easter-themed train rides. Learn more about these special events here. -

Tennessee's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:33 AM

Here’s what to know, who to watch, and how to plan an unforgettable rail-and-whiskey experience in the Volunteer State. -

Michigan's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 09:07 AM

There's a unique thrill in combining the romance of train travel with the rich, warming flavors of expertly crafted whiskeys. -

Massachusetts Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:56 AM

This article dives into some of the alluring aspects of wine by rail in Massachusetts, currently offered by the Cape Cod Central Railroad. -

Maryland Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 09, 26 08:37 AM

This article delves into the enchanting world of wine tasting train experiences in Maryland, providing a detailed exploration of their offerings, history, and allure. -

New York's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:16 AM

For those keen on embarking on such an adventure, the Arcade & Attica offers a unique whiskey tasting train at the end of each summer! -

Florida's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:15 AM

If you’re dreaming of a whiskey-forward journey by rail in the Sunshine State, here’s what’s available now, what to watch for next, and how to craft a memorable experience of your own. -

Colorado Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:14 AM

To truly savor these local flavors while soaking in the scenic beauty of Colorado, the concept of wine tasting trains has emerged, offering both locals and tourists a luxurious and immersive indulgenc… -

Iowa Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 08, 26 10:13 AM

The state not only boasts a burgeoning wine industry but also offers unique experiences such as wine by rail aboard the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad. -

Northern Pacific 4-6-0 1356 Receives Cosmetic Restoration

Mar 07, 26 02:19 PM

A significant preservation effort is underway in Missoula, Montana, where volunteers and local preservationists have begun a cosmetic restoration of Northern Pacific Railway steam locomotive No. 1356. -

New York's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 02:08 PM

Among the Adirondack Railroad's most popular special outings is the Beer & Wine Train Series, an adult-oriented excursion built around the simple pleasures of rail travel. -

Kentucky's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:17 AM

Whether you’re a curious sipper planning your first bourbon getaway or a seasoned enthusiast seeking a fresh angle on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a train excursion offers a slow, scenic, and flavor-fo… -

Ohio's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:15 AM

LM&M's Bourbon Train stands out as one of the most distinctive ways to enjoy a relaxing evening out in southwest Ohio: a scenic heritage train ride paired with curated bourbon samples and onboard refr… -

Georgia 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides In Cordele

Mar 07, 26 10:13 AM

While the railroad offers a range of themed trips throughout the year, one of its most crowd-pleasing special events is the Wine & Cheese Train—a short, scenic round trip designed to feel… -

Arizona Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 07, 26 10:12 AM

For those who want to experience the charm of Arizona's wine scene while embracing the romance of rail travel, wine tasting train rides offer a memorable journey through the state's picturesque landsc… -

Massachusetts's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 09:00 AM

Among Cape Cod Central's lineup of specialty trips, the railroad’s Rails & Ales Beer Tasting Train stands out as a “best of both worlds” event. -

Pennsylvania's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:57 AM

Today, EBT’s rebirth has introduced a growing lineup of experiences, and one of the most enticing for adult visitors is the Broad Top Brews Train. -

Indiana's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:55 AM

Among IRE’s most talked-about offerings is the Wine & Whiskey Train—an adults-only, evening-style trip that leans into the best parts of classic rail travel: atmosphere, comfort, and a little cele… -

North Carolina's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:53 AM

One of the GSMR's most distinctive special events is Spirits on the Rail, a bourbon-focused dining experience built around curated drinks and a chef-prepared multi-course meal. -

Arkansas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:50 AM

This article takes you through the experience of wine tasting train rides in Arkansas, highlighting their offerings, routes, and the delightful blend of history, scenery, and flavor that makes them so… -

California Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 06, 26 08:49 AM

This article explores the charm, routes, and offerings of these unique wine tasting trains that traverse California’s picturesque landscapes. -

Construction Continues On Railroad Museum Of Pennsylvania Roundhouse

Mar 05, 26 01:52 PM

Construction is underway on a long-anticipated roundhouse exhibit building at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, a project designed to preserve several of the most historically signific… -

Wisconsin Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:53 AM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Alabama Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:50 AM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

California's Dinner Train Rides In Sacramento

Mar 05, 26 09:49 AM

Just minutes from downtown Sacramento, the River Fox Train has carved out a niche that’s equal parts scenic railroad, social outing, and “pick-your-own-adventure” evening on the rails. -

New Jersey's Dinner Train Rides In Woodstown

Mar 05, 26 09:48 AM

For visitors who love experiences (not just attractions), Woodstown Central’s dinner-and-dining style trains have become a signature offering—especially for couples’ nights out, small friend groups, a… -

Tennessee Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:46 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:16 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

UP 4014 To Visit WPRM For Fundraising Dinner

Mar 04, 26 11:32 PM

Rail enthusiasts in Northern California will have a rare opportunity this spring as Union Pacific 4014 — the world’s largest operating steam locomotive — is scheduled to visit the Western Pacific Rail… -

CPKC Sets New February Grain Shipping Record

Mar 04, 26 10:57 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) announced on March 3 that it established a new company record for grain transportation during the month of February. -

Hunterdon Wine Express Train Announces 2026 Season Dates

Mar 04, 26 01:57 PM

The Hunterdon Wine Express returns for its 2026 season from April through September, offering a four-hour wine country experience that combines historic rail travel, guided wine tasting, lunch, and ti… -

Washington's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 11:43 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train!